Abstract

We examined PrEP use, condomless anal sex (CAS), and PrEP adherence among men who have sex with men (MSM) attending sexual health clinics in Wales, UK. In addition, we explored the association between the introduction of measures to control transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on these outcomes. We conducted an ecological momentary assessment study of individuals in receipt of PrEP in Wales. Participants used an electronic medication cap to record PrEP use and completed weekly sexual behaviour surveys. We defined adherence to daily PrEP as the percentage of CAS episodes covered by daily PrEP (preceded by ≥ 3 days of PrEP and followed by ≥ 2 days). Sixty participants were recruited between September 2019 and January 2020. PrEP use data prior to the introduction of control measures were available over 5785 person-days (88%) and following their introduction 7537 person-days (80%). Data on CAS episodes were available for 5559 (85%) and 7354 (78%) person-days prior to and following control measures respectively. Prior to the introduction of control measures, PrEP was taken on 3791/5785 (66%) days, there were CAS episodes on 506/5559 (9%) days, and 207/406 (51%) of CAS episodes were covered by an adequate amount of daily PrEP. The introduction of pandemic-related control measures was associated with a reduction in PrEP use (OR 0.44, 95%CI 0.20–0.95), CAS (OR 0.35, 95%CI 0.17–0.69), and PrEP adherence (RR = 0.55, 95%CI 0.34–0.89) and this may have implications for the health and wellbeing of PrEP users and, in addition to disruption across sexual health services, may contribute to wider threats across the HIV prevention cascade.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) involves the use of antiretroviral (ARV) medication for HIV-negative individuals to prevent HIV acquisition through high-risk sexual encounters [1]. Its use has been demonstrated to be highly effective in preventing HIV acquisition in several key populations in the context of large clinical trials [2,3,4] Furthermore, additional analysis of drug concentrations and medication use indicates that HIV-1 risk reduction was 96% and 99% for individuals taking PrEP four and seven days a week respectively, demonstrating its high levels of efficacy [5]. PrEP is now routinely available through healthcare providers in multiple countries worldwide, including Wales (UK), where oral PrEP (tenofovir-emtricitabine (TDF-FTC)) is licensed for daily use in people considered at risk of HIV-acquisition [6]. For PrEP to work as intended, it needs to be taken during periods where an individual is at-risk of acquiring HIV through condomless sexual contact [7].

Adherence to pharmaceutical regimen refers to studying ‘the process by which patients take their medication as prescribed’, and is comprised of treatment initiation (when the patient takes their first dose), implementation (the extent to which a patient's actual dosing corresponds to the prescribed dosing regimen), and persistence (the length of time between initiation and the last dose) [8]. Studying ‘PrEP implementation is particularly complex as it requires careful assessment of both PrEP intake as well as people’s sexual activity.

When TDF-FTC is prescribed for daily use, PrEP adherence can be calculated as ‘the % of days with correct dosing’, which only requires the measurement of medication use. However, other regimens can be followed and have a growing evidence-base (e.g. event-based dosing, which involves taking two pills as a single dose 2–24 h prior to condomless sexual intercourse, followed by one pill a day thereafter until two sex-free days have passed and is thus intrinsically aligned to risk exposure), particularly in men who have sex with men (MSM) [9]. Furthermore, sexual risk behaviour patterns can differ between and within individuals over time and arguably should be aligned to and considered in the context of risk exposure, regardless of regimen [10]. Hence, in relation to the expected prophylactic effects of TDF-FTC, it is most appropriate to define PrEP adherence as ‘the % of condomless sexual encounters adequately covered by PrEP’.

To date, cohort studies enrolling PrEP users and measuring adherence longitudinally in high-income countries have used a range of methods to measure PrEP adherence, including self-report [11] and dried blood spots [12]. A minority of studies measured adherence via a combination of medication use and risk exposure, with those that did doing so via self-report and tending to report lower levels of adherence than studies relying on medication use alone [13]. Electronic monitoring offers a means towards measuring day-to-day medication use (rather than overall consumption over a defined period) and hence may be both best placed to accurately measure implementation of PrEP use over time and align PrEP use with risk episodes, thus offering longitudinal insight into so-called “prevention-effective adherence” and enable understanding of the potential risk associated with non-adherence to PrEP [7]. Within the UK, there are no cohort studies that have measured PrEP use electronically, nor any that have measured adherence via a combination of medication use and risk exposure.

In the absence of such studies in a UK context, the current study set out to assess PrEP adherence in real-life using intensively sampled longitudinal data measuring both electronically-measured PrEP use and condomless sexual behaviour. We aimed to estimate levels of PrEP use, condomless sexual behaviour, and PrEP adherence (using a definition of adherence that aligned electronically monitored PrEP use data with condomless sexual behaviour) in real-life among people receiving TDF-FTC as HIV PrEP through sexual health clinics in Wales, UK.

During our study, the COVID-19 pandemic occurred and control measures were introduced to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2, the respiratory virus that causes COVID-19. These measures included social distancing and advice to restrict journeys outdoors and physical contact with non-household members. Guidance was issued by the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) indicating that people should only have sexual contact with someone if they lived within the same household [14]. Furthermore, sexual health clinics limited contact with clients; in some cases suspending their PrEP service temporarily. The impact of pandemic-related control measures on PrEP use, sexual behaviour, and PrEP adherence among PrEP users living in Wales is as yet unknown, with initial analysis suggesting a marked reduction in condomless anal sex (CAS) in the short-term [15]. The impact of pandemic-related control measures on PrEP use and PrEP adherence is important to understand as it may highlight additional support needs PrEP users require during periods of major change or disruption to their lives. This paper will therefore also consider behaviours within this broader context and determine whether the introduction of control measures was associated with changes in PrEP use, CAS, and PrEP adherence.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This ecological momentary assessment (EMA) [16] study was conducted in sexual health clinics across four health boards (geographically-defined administrative units responsible for planning and delivering health services in their area) offering PrEP in Wales, UK (a nation with a relatively low HIV prevalence of 0.08% in 2019 compared to a global HIV prevalence of 0.7% in the same year [17]). The clinics and health boards were selected for their geographical diversity, serving urban and rural populations. Participants were those in receipt of a prescription of TDF-FTC to prevent HIV-1 and aged at least 16 years. Both new and existing PrEP users were eligible for inclusion and participants were not excluded from the study if they adopted a non-daily regimen. Individuals were excluded if they lacked capacity to consent, were unable to provide a mobile telephone number linked to a smartphone, unable to use the Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) cap (described below), or unable to provide an e-mail address. The study was reviewed and approved by the Wales Research Ethics Committee 3 (Reference Number: 19/WA/0175).

The study is reported in accordance with STROBE [18], EMERGE [19], and CREMAS [20] guidelines for the reporting of observational, medication adherence, and EMA studies. Furthermore, we have used the TEOS framework for our operational definition of PrEP use [21].

Procedures

Participants attending sexual health services to obtain a PrEP prescription were consecutively approached about the study by their treating clinician. Participants who expressed interest were screened as eligible, consented to the study, and completed a questionnaire on a tablet. The questions covered sociodemographic details, health beliefs and behaviours, sex and relationships, the presence and interference of symptoms commonly attributed to PrEP use (identified from the summary of product characteristics for TDF-FTC), and healthcare contacts. Participants were then supplied with a MEMS cap (a medication bottle cap containing an electronic monitor which records the date and time of each opening) [22, 23], shown how to use it (i.e. they were instructed to only open and replace the cap when they were taking their PrEP medication). One-week following recruitment, and thereafter weekly until study participation ended, participants were e-mailed a link to an online survey about condomless anal and vaginal sex (CAS and CVS respectively) during the preceding week. The survey was designed to be completed via mobile, tablet, or computer web browsers (See Table SI in online supplementary material). Reminder e-mails were sent to participants if they had not completed the survey within two days. Follow-up questionnaires, including the same questions asked at recruitment in addition to questions on self-reported PrEP use, were administered at three time points aligning to PrEP clinic follow-ups (approximately three months apart—herein Follow-ups 1, 2, and 3). These initially took place in person within a sexual health clinic. However, following the introduction of measures to control the spread of SARS-CoV-2, these were conducted over the telephone or online. At follow-up time points, participants were asked whether they were experiencing any difficulties using their MEMS caps and reminded how to use them. Data from PrEP clinic notes were also extracted covering the study period.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were:

Daily PrEP use over time, as measured via MEMS-caps [7, 8, 24]. We calculated the percentage of observed days on which PrEP was taken as the total number of days on which PrEP was used (i.e. the MEMS cap was opened at least once) divided by the total number of days over participants were observed during the study. This outcome was measured and reported for all participants (regardless of PrEP regimen followed).

Daily CAS over time was measured via brief, weekly online questionnaires. These captured daily data on whether CAS occurred, the number of times it occurred, and the number of partners with whom it occurred. Questions were informed by previous research (specifically, recommendations for using short recall periods [7, 25] and considering not only if a CAS episode occurred but also the number of times it occurred and number of partners with whom it occurred [26]) and developed by the research team and a stakeholder group comprising current PrEP users, PrEP providers, and individuals involved in sexual health advocacy and policy. They were also piloted prior to use (see Table SI for the list of questions). We calculated the percentage of observed days on which CAS occurred as the total number of days on which at least one CAS episode occurred divided by the total number of days over participants were observed during the study, as well as the mean number of episodes and mean number of partners on a given day. Similar to PrEP use, this outcome was measured and reported for all participants.

As a secondary outcome, we used a working definition of “adherence to daily PrEP”, which considered coverage of CAS episodes by sufficient doses of daily PrEP and was calculated as the percentage of all days on which CAS occurred. For a CAS episode, we considered a sufficient dose of PrEP to comprise at least 3 days of PrEP use prior to the CAS episode and at least two days of PrEP use following a CAS episode [27]. We excluded participants from this analysis if it was indicated in their clinic notes that they were following an event-based regimen.

Sample Descriptives

We collected sociodemographic characteristics of participants, in addition to HIV risk perceptions, stigma, health beliefs, STI diagnoses and treatments, and healthcare resource use. These are reported as frequencies with percentages and medians with interquartile ranges.

Statistical Analysis

The original sample size calculation was based on recruiting 60 participants, with each participant followed up for at least seven months. Assuming some drop out and discontinuation of PrEP use (i.e. an average of 160 days of PrEP use data per individual), this would provide approximately 84% power with a two-sided alpha of 0.05 to estimate an overall average probability of PrEP use on a given day of 0.7, [9] assuming an intra-cluster correlation coefficient of 0.6 [28]. However, we ended up following up participants for approximately nine-months (incorporating up to four clinic visits per participant in total) and thus increasing the potential number of observations available per participant.

Our original plan involved modelling our outcomes across all time points. However, the control measures introduced to reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2 meant that separate consideration of time periods defined by the introduction of control measures would be more meaningful. Observations prior to the introduction of control measures are likely to be more reflective of natural behaviour (and hence reflective of the original aims when first conceptualising the study) and observations following their introduction allow for an investigation of the impact of the pandemic on our outcomes.

To model PrEP use over time, we fitted a two-level mixed-effects logistic regression model (PrEP use—yes/no), which accounted for repeated observations within individuals. We allowed for non-linear patterns in PrEP use over time by modelling time as a restricted cubic spline with four knots [29].

To model sexual behaviour over time, we fitted the following models: (i) a two-level mixed-effects logistic regression model to CAS (yes/no); (ii) a two-level mixed-effects ordered logistic regression model to the number of times a participant engaged in CAS (0/1/2/3 or more); (iii) a two-level mixed-effects ordered logistic regression model to the number of CAS partners (0/1/2 or more). In all three models, time was modelled as a restricted cubic spline with five knots [29]. Time was defined as time since UK control measures were introduced in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (hereafter “control measures”, where time zero was 16/03/2020). This simultaneously facilitated investigation of PrEP use and sexual behaviour over chronological time and supported our exploration and interpretation of the impact of the introduction of pandemic-related control measures across Wales. All models included a variable indicating whether an observation occurred during the intra-pandemic period as a random effect.

See page 2 of the supplementary material for further models fitted to investigate PrEP use and CAS over time.

To examine PrEP adherence over high- risk sexual encounters, we fitted log-binomial regression models to the number of CAS episodes covered by PrEP, with the number of CAS episodes as the exposure and whether the observations occurred during the pre- or intra-pandemic period included as a covariate. We calculated cluster robust standard errors to account for repeated observations within individuals. We conducted a sensitivity analysis whereby we excluded participant time periods (e.g. PrEP adherence data covering study entry to follow-up 1, follow-up 1 to follow-up 2, etc.) where the MEMS cap may have been used inconsistently (see page 2 of the supplementary material for further details).

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata (v16.1) [30].

Results

Participant Recruitment

Between 24/09/2019 and 27/01/2020, clinic staff approached 111 individuals about the study across 23 clinic sessions, of whom 64 agreed to speak to a researcher and 60 were recruited (Fig. 1).

Participant Characteristics

All recruited participants were cis gender and male. The majority identified as white British (53/60, 88.3%), the median age was 35.5 years (IQR 28 to 46 years), 42/60 were in full-time employment (70.0%), and 29/60 were educated to degree level or equivalent (48.3%). New PrEP users (i.e. those who were recruited on the same day they were first prescribed PrEP) accounted for 6/60 of the sample (10.0%). The majority of participants identified as a gay man (56/60, 93.3%), and all but one participant had sex exclusively with other men. Most participants were single at the time they were recruited (46/60, 76.7%). Overall, 27/60 had a documented chronic health condition in their sexual health clinic notes (45.0%) (Table 1). Table SII describes health beliefs and behaviours at study entry. Table SIII describes STI diagnoses and healthcare resource use in the 3 months prior to study entry.

There were zero HIV seroconversions within our participants over the study period.

Data availability

There were seven withdrawals through the study—four withdrew because they were no longer continuing to take PrEP, two because they moved out of Wales so could no longer access PrEP through the NHS in Wales, and one due to bereavement (Fig. 1). All seven participants contributed to the analysis up until the point of their withdrawal. Reported episodes of condomless vaginal sex were rare and limited to a small number of participants within the study. These data were therefore not analysed. Daily PrEP use and CAS data availability are outlined in Table SIV.

Outcomes Measured Prior to the Introduction of Control Measures

PrEP Use

Prior to the introduction of control measures, PrEP was taken on 3791/5785 days (65.5%) and the probability of participants taking PrEP on a given day decreased steadily over time from around 0.8 to just over 0.6 (Table 2; Fig. 2). There was considerable variation in trajectories between participants (Fig. S1).

Overall predicted probabilities of taking PrEP and engaging in condomless anal sex during the pre-pandemic period*. * Solid black line indicates the estimated marginal probability of PrEP use from the PrEP use model. Navy dashed line indicates the estimated marginal probability of engaging in condomless anal sex from the CAS model. Grey circles indicate the observed marginal probabilities of PrEP use. Navy triangles indicate the observed marginal probabilities of condomless anal sex. Jitter effects have been applied to illustrate over-plotting

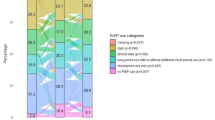

Panel plot of daily PrEP adherence and daily PrEP use over time for four participants (A to D)*. *Left-hand y-axis displays daily PrEP use (yes/no, blue hollow circles). Right-hand y-axis displays whether a CAS episode occurred and whether it was covered by daily PrEP according to our definition (orange lines). X-axis displays time in relation to the introduction of COVID-19 pandemic-related control measures

Sexual Behaviour

Participants reported engaging in CAS on 506/5559 days prior to the introduction of control measures (9.1% of observed days), with a mean number of CAS episodes on a given day of 0.17 (SD = 0.661) and a mean number of partners with whom a participant engaged in CAS on a given day was 0.14 (SD = 0.530), equating to approximately one CAS episode every 6 days and one partner per week, on average. There was a steady increase in the probability of a participant engaging in CAS prior to the introduction of control measures (from 0.07 at the beginning of the observation period to around 0.1 around 60 days prior to the introduction of control measures), before decreasing again to 0.07 as the introduction of control measures neared (Table 3; Fig. 2). Similar to PrEP use, there was considerable variation in CAS between participants (Figs. S1, S2).

Models focusing on the number of times participants engaged in CAS and number of different partners displayed similar patterns to the dichotomous model (Tables SV, SVI; Figs. S3, S4).

PrEP Use and Sexual Behaviour

The model examining the relationship between prior PrEP use and subsequent CAS included 11,500 observations within 58 participants. We found that prior PrEP use was associated with almost two-fold higher odds of subsequent CAS (OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.16–3.23, z = 2.53, p = 0.011).

PrEP Adherence

PrEP adherence was assessed for 406 CAS episodes over 4801 days prior to the introduction of control measures. In daily PrEP users, PrEP use was adequate to cover 207 (51.0%) CAS episodes, with 10/49 (20.4%) participants taking daily PrEP to cover all CAS episodes. In our sensitivity analysis excluding participant data where there was suspected inconsistent use of the MEMS cap, PrEP adherence was assessed for 329 CAS episodes over 4,097 days and PrEP use was adequate to cover 205 (62.3%) CAS episodes.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The odds of participants taking PrEP on a given day were 56% lower following the introduction of control measures (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.95, z = − 2.09, p = 0.037) (Table 2). As illustrated by Figure S5, there was a statistically significant difference in slopes pre- and during the pandemic [χ2(3) = 8.24, p-value for joint test of interaction terms = 0.041].

Similarly, the introduction of control measures was associated with a marked reduction in CAS (OR averaged over time during the pandemic = 0.35, 95% CI 0.17–0.69, z = − 2.99, p = 0.003) (Table 3; Fig. S5). There was no evidence to suggest a difference in slopes pre- and during the pandemic [χ2(3) = 5.67, p-value for joint test of interaction terms = 0.129].

We found some indication that the association between prior PrEP use and subsequent CAS was higher following the introduction of control measures compared to the time prior to their introduction. However, this association was not statistically significant (OR for prior PrEP use × pandemic time interaction = 1.56, 95% CI 0.98–2.47, z = 1.88, p = 0.060).

Following the introduction of control measures, PrEP adherence was assessed for 311 CAS episodes over 6,076 days. In daily PrEP users, PrEP use was adequate to cover 88 (28.3%) CAS episodes (RR = 0.55, 95% CI 0.34–0.89, z = − 2.42, p = 0.015), with 4/46 (8.7%) participants taking daily PrEP to cover all CAS episodes. Our sensitivity analysis encompassed 214 CAS episodes over 4407 days and PrEP use was adequate to cover 78 (36.4%) CAS episodes (RR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.36–0.94, z = − 2.21, p = 0.027).

PrEP adherence varied between- and within-individuals over time, with some participants displaying high levels of PrEP adherence over time and others less so. Figure 3 and Table S7 illustrate the different patterns of PrEP use and PrEP adherence and different impacts of pandemic-related control measures within our dataset. For example, Participant A demonstrated high levels of daily PrEP use and CAS, most of which were covered by adequate amounts of PrEP, with no discernible change in these patterns following the introduction of control measures. Participant B demonstrated similarly high levels of daily PrEP use and less frequent CAS episodes prior to the introduction of control measures. Following their introduction, the participant paused their PrEP use and restarted when CAS behaviour resumed. Note their first reported CAS episode was not covered by an adequate amount of PrEP according to our definition. Participant C demonstrated more frequent CAS episodes and lower adherence following the introduction of control measures. Participant D demonstrated high levels of daily PrEP use and CAS prior to the introduction of control measures, with a cessation of both PrEP use and CAS following their introduction.

Discussion

Summary of Main Findings

In our study of PrEP users in Wales, we found considerable variation between- and within-individuals in their PrEP use and sexual risk behaviours over time. While our study indicated that PrEP users tailor their PrEP use according to their risk exposure (i.e. that prior PrEP use is associated with subsequent CAS), we found that only 51 to 63% of CAS episodes were covered by an adequate supply of PrEP among daily PrEP users.

The introduction of measures to control the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was associated with marked reductions in both PrEP use and CAS episodes. We found some evidence to suggest that PrEP users were more likely to tailor their PrEP use according to their risk exposure (though this was not statistically significant), yet despite this only 28 to 36% of CAS episodes were covered by an adequate intake of PrEP among daily PrEP users.

Strengths and Limitations

We used intensive longitudinal methods, benefitting from frequent measurement of observations within individuals over time, rather than relying on a measure collected at a single point in time or infrequent repeated observations. Measures collected at a single point in time would not allow for an understanding of temporal trends and may be more prone to recall bias and measurement error. Infrequent repeated observations may have lacked sensitivity to detect within-person changes and the interrelationship between PrEP use and sexual behaviour. We achieved high levels of follow-up for both PrEP use and sexual behaviour. By measuring PrEP use using an electronic monitor, we utilised a non-intrusive method to capture PrEP use which was unlikely to be subject to measurement reactivity in the same way that self-report and tablet count measurement approaches may be [31, 32]. By capturing CAS behaviour using brief weekly electronic surveys, we limited response burden both in terms of time spent completing questions as well as the recall period. We sampled participants across four of the seven health boards offering PrEP through the NHS in Wales, and included a nationally representative sample of participants covering 5% of all individuals accessing PrEP through the NHS in Wales at the time.

The study was designed to include all PrEP users. However, only MSM were included and the majority of participants were white. While this is largely representative of the individuals accessing PrEP through NHS Wales, the findings may not generalise to other key populations.

The weekly sexual behaviour surveys were intentionally kept brief to reduce response burden, but doing so may have limited the information that they provide. For example, while the number of CAS episodes and number of different partners were recorded, no differentiation between partner types was made [33]. Furthermore, the use of the MEMS relied on the assumption that each cap opening corresponding to an individual removing and ingesting one tablet. The levels of PrEP adherence found in our study may in part be explained by these two aspects.

Finally, while a key strength of this study is that it was set-up in advance of the COVID-19 pandemic, allowing for longitudinal measures of both PrEP use and CAS prior to and following the introduction of control measures, the number of observations available prior to their introduction (and hence our ability to study natural behaviour as per the original aim of the study), was limited.

Comparisons with Existing Literature

Our finding of a gradual decrease in PrEP use over time is consistent with findings from a demonstration project in New South Wales, which indicated a decline in daily PrEP adherence over time across a range of measures [34]. However, while the study measured adherence in various ways, its definition was based on PrEP use only and not within the context of risk exposure. Adherence to PrEP was lower in our study than previously reported [35, 36]. This may be explained by different definitions of adequate PrEP intake and risk exposure, but also by the different geographical settings, HIV incidences and PrEP use measures (electronic monitor versus self-report). Our findings align with a recent survey of young sexual minority men in the US found PrEP use and sexual activity decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic, with over a third reporting CAS with a casual partner three-months or later after the introduction of pandemic-related control measures [37].

Implications

Our work highlights varying levels of PrEP use and CAS over time, with PrEP adherence estimated to be lower than that typically found in other PrEP cohorts. Furthermore, the introduction of pandemic-related control measures was associated with a substantial reductions in all three outcomes. The reduction in both CAS and PrEP adherence implies that while reduced in number, participants engaging in CAS following the introduction of pandemic-related control measures were less likely to be covered by PrEP and therefore may be associated with greater risk of HIV-transmission. These findings may have implications for the health and wellbeing, and in particular the sexual wellbeing of PrEP users [38]. Furthermore, lower levels of PrEP adherence coupled with disruption to (or alteration of) sexual health services may pose a risk in terms of new HIV diagnoses and thus contribute to the wider threats across the HIV prevention cascade [39]. Policy decision-making and public health messaging should factor in the role of sexual wellbeing on future pandemic restrictions or other restrictions where both access to sexual health services and social interaction may be affected.

Further work is needed to investigate the within-individual behavioural determinants of PrEP use, CAS, and PrEP coverage over time; gain a deeper understanding of the experiences of PrEP and the impact that the pandemic had on PrEP use and sexual risk behaviours; determine the extent to which PrEP non-adherence in this study reflects genuine risk exposure or undocumented changes in relationship dynamics; understand the longer-term impact on the health and wellbeing of PrEP users as we emerge from the pandemic.

Greater emphasis should be placed on supporting long-term PrEP adherence, with post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) offered in circumstances whereby CAS episodes are not covered by an adequate intake of PrEP.

Conclusion

Daily PrEP use, CAS, and PrEP adherence is highly variable between- and within- MSM PrEP users in Wales over time. A high proportion of CAS episodes were not covered by adequate PrEP use, and the introduction of pandemic-related control measures was associated with substantial reductions in PrEP use, CAS, but most concerning PrEP adherence. The latter of these findings warrants further investigation to determine the risk associated with CAS episodes not covered by PrEP.

Data availability

Data are available upon request.

References

World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS: Pre-exposure prophylaxis [Internet]. [cited 2021 May 9]. Available from: https://www.who.int/hiv/topics/prep/en/

Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1011205.

Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7.

McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, Dolling DI, Gafos M, Gilson R, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2.

Anderson PL, Glidden D V, Liu A, Buchbinder S, Lama JR, Guanira JV, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med. 2014;4(151):151ra125.

Gething V. Written statement: Availability of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV [Internet]. Welsh Government. 2020 [cited 2021 May 9]. Available from: https://gov.wales/written-statement-availability-pre-exposure-prophylaxis-prep-prevent-hiv

Haberer JE. Current concepts for PrEP adherence in the PrEP revolution. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2016;11(1):10–7.

Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, Przemyslaw K, Demonceau J, Ruppar T, et al. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(5):691–705.

Molina J-M, Charreau I, Spire B, Cotte L, Chas J, Capitant C, et al. Efficacy, safety, and effect on sexual behaviour of on-demand pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in men who have sex with men: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(9):e402–10.

Haberer JE, Kidoguchi L, Heffron R, Mugo N, Bukusi E, Katabira E, et al. Alignment of adherence and risk for HIV acquisition in a demonstration project of pre-exposure prophylaxis among HIV serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda: a prospective analysis of prevention-effective adherence: A. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):1–9.

Pečavar B, Kokošar Ulčar B, Kordiš M, Pleško M, Turel G, Vovko T, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV with oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine in men who have sex with men: Slovenian national demonstration project. Int J STD AIDS. 2021;32(11):1060–5.

Goodman-Meza D, Beymer MR, Kofron RM, Amico KR, Psaros C, Bushman LR, et al. Effective use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) Among stimulant users with multiple condomless sex partners: a longitudinal study of men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. AIDS Care Psychol Socio-Medical Asp AIDS/HIV. 2019;31(10):1228–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2019.1595523.

Jongen VW, Hoornenborg E, van den Elshout MAM, Boyd A, Zimmermann HML, Coyer L, et al. Adherence to event-driven HIV PrEP among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam, the Netherlands: analysis based on online diary data, 3-monthly questionnaires and intracellular TFV-DP. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(5):e25708.

British Association for Sexual Health and HIV. BASHH ISSUES GUIDANCE ON SEX, SOCIAL DISTANCING AND COVID-19 [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jan 17]. Available from: https://www.bashh.org/news/news/bashh-issues-guidance-on-sex-social-distancing-and-covid-19/

Gillespie D, Knapper C, Hughes D, Couzens Z, Wood F, de Bruin M, et al. Early impact of COVID-19 social distancing measures on reported sexual behaviour of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis users in Wales. Sex Transm Infect. 2021;97(2):85–7.

Smiley SL, Milburn NG, Nyhan K, Taggart T. A systematic review of recent methodological approaches for using ecological momentary assessment to examine outcomes in U.S. Based HIV Research. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2020;17(4):333–42.

Kaiser Family Foundation. The Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2022 Jan 21]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/fact-sheet/the-global-hivaids-epidemic/

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9.

De Geest S, Zullig LL, Dunbar-Jacob J, Helmy R, Hughes DA, Wilson IB, et al. ESPACOMP medication adherence reporting guideline (EMERGE). Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(1):30–5.

Liao Y, Skelton K, Dunton G, Bruening M. A systematic review of methods and procedures used in ecological momentary assessments of diet and physical activity research in youth: an adapted STROBE checklist for reporting EMA Studies (CREMAS). J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(6):1–12.

Dima AL, Allemann SS, Dunbar-Jacob J, Hughes DA, Vrijens B, Wilson IB. TEOS: A framework for constructing operational definitions of medication adherence based on timelines–events–objectives–sources. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;87(6):2521–33.

Urquhart J. The electronic medication event monitor. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32(5):345–56.

Abaasa A, Hendrix C, Gandhi M, Anderson P, Kamali A, Kibengo F, et al. Utility of different adherence measures for PrEP: patterns and incremental value. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1165–73.

El Alili M, Vrijens B, Demonceau J, Evers SM, Hiligsmann M. A scoping review of studies comparing the medication event monitoring system (MEMS) with alternative methods for measuring medication adherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;82(1):268–79.

Haberer JE, Ngure K, Muwonge T, Mugo N, Katabira E, Heffron R, et al. Context matters: PrEP adherence is associated with sexual behavior among HIV serodiscordant couples in East Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76(5):488–92.

de Bruin M, Viechtbauer W. The meaning of adherence when behavioral risk patterns vary: obscured use- and method-effectiveness in HIV-prevention trials. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e44029. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0044029.

Fonsart J, Saragosti S, Taouk M, Peytavin G, Bushman L, Chareau I, et al. Single-dose pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral tenofovir and emtricitabine in blood, saliva and rectal tissue: a sub-study of the ANRS IPERGAY trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(2):478–85.

Gillespie D, Hood K, Farewell D, Stenson R, Probert C, Hawthorne AB. Electronic monitoring of medication adherence in a 1-year clinical study of 2 dosing regimens of mesalazine for adults in remission with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(1):82–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MIB.0000437500.60546.2a.

Harrell FE Jr. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer; 2001.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2019.

Mboup A, Béhanzin L, Guédou F, Giguère K, Geraldo N, Zannou DM, et al. Comparison of adherence measurement tools used in a pre-exposure prophylaxis demonstration study among female sex workers in Benin. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(21):e20063.

Corneli AL, McKenna K, Perry B, Ahmed K, Agot K, Malamatsho F, et al. The science of being a study participant: FEM-PrEP participants’ explanations for overreporting adherence to the study pills and for the whereabouts of unused pills. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68(5):578–84.

Estcourt CS, Flowers P, Cassell JA, Pothoulaki M, Vojt G, Mapp F, et al. Going beyond ‘regular and casual’: development of a classification of sexual partner types to enhance partner notification for STIs. Sex Transm Infect. 2021; Sextrans-2020-054846. Available from http://sti.bmj.com/content/early/2021/04/28/sextrans-2020-054846.abstract

Vaccher SJ, Marzinke MA, Templeton DJ, Haire BG, Ryder N, McNulty A, et al. Predictors of daily adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in gay/bisexual men in the PRELUDE demonstration project. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(5):1287–96.

Vuylsteke B, Reyniers T, De Baetselier I, Nöstlinger C, Crucitti T, Buyze J, et al. Daily and event-driven pre-exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men in Belgium: results of a prospective cohort measuring adherence, sexual behaviour and STI incidence. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(10):1–9.

Bavinton BR, Vaccher S, Jin F, Prestage GP, Holt M, Zablotska-Manos IB, et al. High levels of prevention-effective adherence to HIV PrEP: an analysis of substudy data from the EPIC-NSW Trial. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;87(4):1040–7.

Hong C, Horvath KJ, Stephenson R, Nelson KM, Petroll AE, Walsh JL, et al. prep use and persistence among young sexual minority men 17–24 years old during the COVID-19 pandemic. AIDS Behav. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03423-5.

Mitchell KR, Lewis R, O’Sullivan LF, Fortenberry JD. What is sexual wellbeing and why does it matter for public health? Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(8):e608–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00099-2.

Newman PA, Guta A. How to Have Sex in an Epidemic Redux: Reinforcing HIV Prevention in the COVID-19 Pandemic. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(8):2260–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02940-z.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the participants recruited as part of the DO-PrEP study, without whom this work would not be possible. We would also like to acknowledge all sexual health clinicians across Aneurin Bevan, Cardiff & Vale, Betsi Cadwaladr, and Swansea Bay health boards who supported this study. We would like to acknowledge members of the DO-PrEP stakeholder group (Lisa Power, Nicholas Hobbs, George Barker, Karen Cameron, and Marion Lyons), staff involved with work in the sexual health clinics from which participants were recruited (Irene Parker, Amy Harris, Amanda Blackler, Kim Mitchell, Leasa Green, Olwen Williams), and individuals involved in the set-up and conduct of the study (Sam Clarkstone, Rebecca Milton, Rebecca Cavanagh, and Kerry Nyland). We would like to acknowledge the ongoing work of Fast Track Cardiff & Vale (https://fasttrackcardiff.wales/), to which this project is partnered. The Centre for Trials Research is funded by Health & Care Research Wales and Cancer Research UK.

Funding

The DO-PrEP study was funded by the Welsh Government through Health and Care Research Wales (Project ref HF-17-1411). The funder had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The corresponding author confirms that they had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DG led the design, collected data, conducted statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. DH, ZC, FW, MdB, RM, AJ, and KH contributed to the design of the study and the analysis. DG and KH verified the underlying data. All authors contributed to the interpretation and critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

DG and KH report receiving funding from Health and Care Research Wales during the conduct of this work. KH also reports a leadership role for Cardiff University on the Fast Track Cardiff & Vale leadership group. This group is a local branch of the Fast Track Cities initiative aiming to eradicate HIV by 2030. RM reports funding from National Institute for Health Research during the conduct of this study. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the Wales Research Ethics Committee 3 (Reference Number: 19/WA/0175).

Informed Consent

Participants provided informed consent to participate and for anonymised data to be used in publications.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gillespie, D., Couzens, Z., de Bruin, M. et al. PrEP Use, Sexual Behaviour, and PrEP Adherence Among Men who have Sex with Men Living in Wales Prior to and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. AIDS Behav 26, 2746–2757 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03618-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03618-4