Abstract

This study aimed to explore whether there were differences in suicidal ideation at different time points among sexual minority men (SMM) within five years of HIV diagnosis, and to investigate the influence of time and psychosocial variables on suicidal ideation. This was a five-year follow-up study focusing on the suicidal ideation among HIV-positive SMM who were recruited when they were newly diagnosed with HIV. Suicidal ideation and psychosocial characteristics including depression, anxiety, HIV-related stress, and social support were assessed within one month, the first year, and the fifth year after HIV diagnosis. A total of 197 SMM newly diagnosed with HIV completed three-time point surveys in this study. The prevalence of suicidal ideation was 27.4%, 15.7%, and 23.9% at one month, the first year, and the fifth year after HIV diagnosis, respectively. The risk of suicidal ideation was lower in the first year than baseline, but there was no significant difference between the fifth year and baseline. Emotional stress and objective support independently predicted suicidal ideation and they had interactions with time. The suicidal ideation of SMM newly diagnosed with HIV decreased in the first year and then increased in the fifth year, not showing a sustained decline trend in a longer trajectory of HIV diagnosis. Stress management, especially long-term stress assessment and management with a focus on emotional stress should be incorporated into HIV health care in an appropriate manner. In addition, social support should also be continuously provided to this vulnerable population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Suicidal behavior is recognized as a spectrum which covers a range of continuum acts from suicidal ideation, suicide plan, attempted suicide to completed suicide [1]. Suicidal ideation is the first step towards suicide and has been shown to predict later suicide plan, suicide attempt and completed suicide [2, 3]. In light of the key role of suicidal ideation in suicide, it has been recommended as an evaluation index for suicide prevention [4].

Suicide among sexual minority men (SMM) who are HIV-positive has become a growing major public health problem and has attracted concerns among scholars worldwide [5,6,7,8,9]. SMM are broadly defined (a) men who have sex with men, or (b) men who self-identify as gay or bisexual men, or (c) men who are intensely attracted to men [10]. Because of non-heterosexual orientation, SMM experience significant mental health problems in China, including suicidal ideation [11,12,13,14]. In recent years, the suicidal ideation of SMM has become a topic of increasing concern as the increasing HIV prevalence among SMM [15]. A meta-analysis in 2017 pointed out that the pooled lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation was 34.97% among general SMM [16]. In addition, a few published studies have concluded that HIV-positive SMM are more likely to experience suicidal ideation [5,6,7,8,9]. Therefore, this vulnerable subgroup deserves more research attention.

Suicidal ideations are affected by some common psychosocial factors, including HIV-related stress, depression, anxiety, and social support. HIV-related stress refers to stressfulness from HIV/AIDS-specific stressors and can take various forms, such as concerns about disclosure, hesitation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), HIV-related stigma, and worry about physical changes [17]. Studies have shown that HIV-related stress was associated with worse mental health and even suicidal ideation [18, 19]. Depression and anxiety are two common types of emotional distress that have also been shown to be risk factors for suicidal ideation among HIV-positive SMM [20, 21]. In addition, social support has been widely recognized as a moderator that can buffer the negative effects of HIV diagnosis among SMM, including suicidal ideation [22]. It is thus important to understand these psychosocial variables to identify the risk of suicidal ideation and implement further targeted intervention to reduce such risk among HIV-positive SMM.

Suicidal ideation is also a variable that may change overtime, particularly in the first year after HIV diagnosis [23]. There may be disparities in suicidal ideation at different time points after HIV diagnosis. But to our knowledge, most studies on suicidal ideation and associated factors among SMM living with HIV are cross-sectional [5,6,7,8,9]. There is a lack of longitudinal study, especially for longer than one-year follow-up study. In addition, some psychosocial characteristics, such as social support and stress, are also time-dependent variables [24]. It is thus important to understand how the effects of psychosocial characteristics on suicidal ideation change over time. The current study was conducted to fill in the research gap with the following purposes: (1) to explore whether there were differences in suicidal ideation among SMM with newly diagnosed HIV at different time points within five years. (2) to investigate the psychosocial factors associated with suicidal ideation among SMM living with HIV after adjusting for the covariates.

Methods

Participants

This five-year longitudinal observational study was conducted at the HIV Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT) outpatient department of Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Changsha, Hunan Province, China. Participants were consecutively recruited from 1st March 2013 to 30th September 2014. Eligible participants had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (a) aged above 18 years old, (b) resided in Changsha over 6 months, (c) diagnosed as HIV infection for no more than one month.

Setting and Procedure

We established a cohort of individuals who had been newly diagnosed with HIV. Baseline survey was conducted between 1st March 2013, and 30th September 2014 at Changsha CDC. The first and second follow-up surveys were conducted at the Changsha CDC and Changsha Hospital for Infectious Diseases in the first year and the fifth year after HIV diagnosis, respectively. For the two follow-up surveys, information on participants who had and had not initiated ART was collected at the Changsha Hospital for Infectious Diseases, and Changsha CDC, respectively. After providing written informed consent, all participants were invited to complete a questionnaire by face-to-face interviews at baseline and two follow-up time points. With the consent of the participants, our team used the Chinese HIV/AIDS Comprehensive Response Information Management System (CRIMS) to obtain HIV-related clinical information, including whether the participants had initiated antiretroviral therapy (ART) during the two follow-up periods and their CD4 cell counts.

Measurements

Dependent Variable

Suicidal Ideation

In this study, the main outcome suicidal ideation was assessed by two questions based on two items adapted from the section of World Mental Health-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI) suicidality assessment [25], which were also used in other similar studies [26,27,28]. In the baseline survey, participants were asked “Have you seriously considered taking suicide after HIV diagnosis?” and in the two follow-up surveys, participants were asked "Have you seriously considered taking suicide in the last year?" The answer of each question is dichotomized, with “yes” representing presence of suicidal ideation.

Explanatory Variables

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed by the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Scale (PHQ-9), which is a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3 [29]. A higher score indicates more severe depressive symptoms, with a cut-off point of 10 for significant depressive symptoms [30]. In this study, we used the Chinese version of PHQ-9 translated by Wang et al., which has shown good reliability and validity [31]. In the current study, the PHQ-9 showed good internal consistency with a Cronbach's α coefficient of 0.903.

Anxiety Symptoms

Anxiety symptoms were assessed by the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire (GAD-7), which is a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3 [32]. A higher score indicates more severe anxiety symptoms, with a cur-off point of 10 for significant anxiety symptoms [33]. In this study, we used the Chinese version of GAD-7 translated by He et al., which has shown good reliability and validity [34]. In the current study, the GAD-7 showed good internal consistency with a Cronbach's α coefficient of 0.936.

HIV-Related Stress

HIV-related stress was measured by the 17-item Chinese HIV/AIDS Stress Scale (CSS-HIV), which covers three dimensions: emotional stress, social stress, and instrumental stress. It is a 5-point Likert-type scale, with a higher score suggesting a higher stress level [35]. The scale was originally compiled by Pakenham [36] and later translated into Chinese by Niu et al., which has shown good reliability and validity [35]. In the current study, the CSS-HIV showed good internal consistency with a Cronbach's α coefficient of 0.911.

Social Support

Social support was assessed by the 10-item Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS), which covers three dimensions: objective support, subjective support and support utilization [37]. The total score ranges from 12 to 66, with a higher score indicating more social support. In this study the SSRS showed good internal consistency with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.820.

Covariates

Socio-Demographic Information

Socio-demographic information was collected by a questionnaire, which included: age (18–29, > 29), marital status (married, unmarried), sexual orientation (gay, bisexual), monthly income (≤ 4000, > 4000 yuan), education (college or higher, senior or lower), employment (employed, unemployed), household registration (rural, urban).

HIV-Related Clinical Information

HIV-related clinical information was collected from CRIMS, which included CD4 counts and antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation status.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were expressed as the median of frequency, percentage, and interquartile range (IQR). In order to compare the baseline sample characteristics of participants who completed the follow-up surveys and those who dropped out, the chi-square test was used for comparison of categorical variables, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparison of continuous variables.

We used the logistic regression with generalized estimation equation (GEE) method to determine time and psychosocial factors (depressive and anxiety symptoms, HIV-related stress, and social support) associated with suicidal ideation among SMM newly diagnosed with HIV. One advantage of the GEE method is the applicability of a wide range of data to dependent variables for repeated measurements [38]. With suicidal ideation as the dependent variable, 3 independent multivariable GEE models were used for the study. In Model 1, we entered only time factors and depressive and anxiety symptoms. In Model 2, we added three dimensions of HIV-related stress scores based on Model 1. In Model 3, we included three dimensions of social support scores based on model 2. To see whether the effects of psychosocial variables on suicidal ideation changed over time, we examined the interaction between time factors and significant psychosocial variables in multivariate GEE models. All models adjusted for age, marital status, education, household registration, sexual orientation, employment, monthly income, CD4 cell counts, and ART initiation status. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows 26.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethical Approval and Consideration

All participants provided written informed consent. In addition, an emergency plan was developed for participants who presented serious suicidal ideation during the interview. A reporting process will be initiated according to the emergency plan, and the investigator immediately informed the CDC staff, who would take appropriate procedures to help the participants. Moreover, the study team will also provide referral information of professional psychological crisis intervention institutions for participants in need.

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 1,267 people was newly diagnosed with HIV in Changsha during the baseline survey period. Of the 855 people who met the criteria for inclusion, 557 participated in the study. We finally included a total of 354 individuals who reported themselves as SMM in this study, 258 of whom completed the first follow-up survey and 197 completed the second follow-up survey. Figure 1 shows the detailed flowchart of participant enrollment.

All baseline sample characteristics were not significantly different between 197 participants who completed the three-time surveys and 157 of those lost to follow-up (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1 shows baseline sample characteristics. Most of the participants who completed the second follow-up survey were in the 18–29 age group (65.5%), unmarried (84.8%), gay (65.0%), employed (71.1%).

The Trajectory of Suicidal Ideation and Psychological Characteristics

Table 2 shows the differences in suicidal ideation and psychosocial characteristics between the baseline and two follow-up surveys. The prevalence of suicidal ideation was 27.4% at baseline, 15.7% after one year, and 23.9% after five years. In terms of psychosocial characteristics, the prevalence of depressive symptoms was 42.1% at baseline, 12.2% after one year, and 16.2% after five years. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms was 29.4% at baseline, 12.7% after one year, and 11.2% after five years. In addition, the five-year trajectory of suicidal ideation among the HIV-positive SMM is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Suicidal Ideation at Each Time Point

Table 3 shows the proportion of participants with or without suicidal ideation at each time point. 51.7% of participants did not report suicidal ideation at all three time points. 13.7% of participants reported suicidal ideation only at baseline. 12.2% of participants reported suicidal ideation only in the fifth year. In addition, 3.6% of participants reported suicidal ideation at all three time points.

Factors Associated With Suicidal Ideation

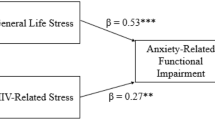

Table 4 shows risk factors associated with suicidal ideation among SMM newly diagnosed with HIV at the three-time points using multivariate GEE models. Associated factors of suicidal ideation at three-time points included in model 3: first year after HIV diagnosis (OR: 0.35; 95% CI: 0.17, 0.70); unmarried (OR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.22, 0.75), bisexuality (OR: 1.87; 95% CI: 1.12, 3.11), ART initiation (OR: 2.55; 95% CI: 1.20, 5.43), emotional stress (OR: 1.23; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.33), and objective support (OR: 0.86; 95% CI: 0.77, 0.96).

Interactions Between Psychosocial Variables and Time

Table 5 shows interaction effect between time and psychosocial variables at three time points by multivariate analysis. Significant negative interaction between time and emotional stress, and significant positive interaction between time and objective support were found at three time points.

Discussion

In this study, the baseline prevalence of suicidal ideation among SMM when they were newly diagnosed with HIV was 27.4%, which was higher than the lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation among the general Chinese SMM [39]. The risk of suicidal ideation was lower one year after HIV diagnosis than one month within HIV diagnosis. However, there was no significant difference in the risk of suicidal ideation between the fifth year after HIV diagnosis and one month within HIV diagnosis. Emotional stress and objective support were independent predictors for suicidal ideation. There are interactions between time and emotional stress and objective support during the five-year follow-up period. The effect of emotional stress on suicidal ideation had slightly diminished over time, while the effect of objective support on suicidal ideation had slightly increased over time. Other factors, including married status and ART initiation status were also shown to be risk factors for suicidal ideation in both type of models, which may provide some new viewpoints for suicide prevention among SMM living with HIV.

Our data revealed that risk of suicidal ideation had decreased over time during the first year after diagnosis. This may be explained by the phenomenon of post-traumatic growth which refers to the positive psychological consequences of struggling with a traumatic event [40]. Some studies have found that the pathogenic effects of trauma are more common among people living with HIV than general population, even in a society with universal access to effective HIV-related medical health care [41, 42]. With the widespread use of ART, HIV infection has transformed from an acute life-threatening disease into a chronic remediable disease that can be managed. As Rzeszutek revealed in a systematical review, although being diagnosed with HIV is a traumatic event that can be stressful, many people living with HIV have positively learned HIV-related knowledge, actively sought for medical care, and gradually recognized that HIV infection was treatable [43]. Thus, they have adapted to the HIV-positive status over time and gained a new commitment to personal goals and life [44].

Another important finding was that the risk of suicidal ideation was not significantly different in the fifth year after HIV diagnosis from one month within HIV diagnosis. Contrary to our expectation, there was no sustained declining or flat trend in suicidal ideation in the longer trajectory of HIV infection over five years. This finding may be related to HIV-related stigma. During the post-traumatic period, additional distress caused by HIV-related stigma was negatively associated with post-traumatic growth outcomes [45]. In China, people living with HIV are mostly infected through activities that are usually considered immoral, especially for SMM who are considered promiscuous [46, 47]. Moreover, in traditional Chinese culture, SMM themselves are stigmatized due to their sexual minority status [48]. When SMM are infected, they will gradually face more troubles in life, work and interpersonal relationships than general people living with HIV because of the “double stigma” [49]. Furthermore, HIV-positive SMM face many difficulties in finding a same-sex sexual partner if their HIV-positive status is known to others [50]. Therefore, HIV clinicians should recognize that suicide ideation not only peak soon after HIV diagnosis, but also increased after a longer period of HIV diagnosis among SMM. This finding has implications for future suicide prevention program to screen for suicidal ideation at multiple stages after the diagnosis of HIV infection among SMM.

We found that the emotional stress dimension of HIV-related stress was associated with suicidal ideation. When emotional stress scores were higher, the risk of suicidal ideation was higher. In China, personal motivation (such as feeling depressed, desperate and wanting to escape pain) was more recognized as risk factors of suicidal ideation than interpersonal factors [51, 52]. In addition, according to the minority stress theory, SMM is a social subgroup that is vulnerable to stigma and discrimination due to same-sex behavior or orientation, which makes them more prone to excessive stress and mental health disorders [53]. SMM living with HIV often face “double stress” from not only HIV infection, but also sexual minority status [53]. Moreover, the interaction results at three-time point showed that the effect of emotional stress on suicidal ideation diminished slightly over time during a five-year period after HIV infection. This finding indicates there is a strong need to integrate mental health services especially stress management within HIV care facilities for SMM living with HIV in an appropriate manner.

Depression and anxiety are recognized as important risk factors for suicidal ideation [54, 55]. The presence of a clinically active major depressive episode may be a strong predictor of suicidal ideation [56]. In GEE Model 1, we found that depressive and anxiety symptoms are risk factors for suicidal ideation, which is consistent with most studies [57, 58]. However, this effect disappeared when HIV-related stress was included in the GEE model. The findings suggest that HIV-related stress is a stronger predictor of suicidal ideation than depression and anxiety symptoms among SMM living with HIV. This may be due to the fact that individuals may have a transient increase in emotional response and develop transient, sudden suicidal ideation following excessive stress [59, 60]. These findings suggest that psychosocial characteristics are important predictors of suicide ideation. There is an urgent need to increase psychological counseling services for common psychological disorders such as depression, anxiety symptoms, and stress in HIV management and care.

This study found that higher objective support dimension of social support scores were associated with lower risk of suicidal ideation. This suggests that practical support, such as direct financial assistance, social networks of family, friends, and colleagues, as well as the presence and involvement of group relationships, can persistently help SMM to cope better with the stress of being diagnosed with HIV. Unfortunately, the overall level of social support in the participants is low. Moreover, the interaction results showed that the effect of objective support on suicidal ideation enhanced slightly over time during the five-year period after HIV infection. This finding suggest that social support need to be provided continuously to SMM living with HIV. One thing noteworthy is that the risk of suicidal ideation was higher in the married participants, contrary to previous studies in general people living with HIV [61]. In China, most of SMM choose to hide their real sexual orientation and marry women under stress from society and family [62]. According to a previous study, about 80% of SMM eventually married a woman in China [63]. After being diagnosed with HIV, SMM not only face the psychological stress of disclosing their HIV status to their wives, but also the additional stress of disclosing their sexual minority. Therefore, it is important to recognize that marriage does not increase the level of social support for Chinese SMM living with HIV.

Our study showed that participants who initiated ART had a higher risk of suicidal ideation, which is contrary to previous study [64]. This finding may be partly explained by the side effects of ART. For instance, efavirenz containing non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) in ART may cause severe adverse reactions in the central nervous system [65]. The drug can cause mental disorders such as severe depression and suicidal ideation. In addition, people who have just initiated ART may fear that their HIV-positive status will be exposed, which constitutes a huge barrier for drug adherence [66]. Therefore, maladaptive drug side effects and poor drug adherence may contribute to increased suicidal ideation during the early stage of ART treatment 67. This finding suggests that special attention need to be paid to the mental health status of people infected with HIV who just initiated ART, and during the long-term treatment process.

There are limitations to this study. First, the non-random sampling method may limit the generalization of the results in this study. Second, we rely on self-reported scales to assess psychosocial characteristic. In order to provide a more reliable measure of psychosocial characteristics, professional diagnostic tools should be included in the assessment of psychosocial characteristics in future studies. Third, the time intervals of our longitudinal data collection are unbalanced, this may cause some information to lose during the five-year follow-up periods. Finally, more than 40% of the participants dropped out at five-year follow-up, which may bring about potential bias. However, a careful comparison of sample characteristics between those who dropped out and those who retained showed no significant difference, indicating that our conclusion should be valid (Details are provided in Table S1).

Conclusion

The suicidal ideation of SMM living with HIV decreased in the first year and then increased in the fifth year, not showing a sustained decline trend in a longer trajectory of HIV diagnosis. Our findings may have considerable implications for HIV clinicians and relevant policy makers to develop more effective interventions to reduce the risk of suicidal ideation among SMM living with HIV not only in the early stages of HIV diagnosis, but also in the longer period after HIV diagnosis. Moreover, we need to provide timely professional psychological crisis intervention when suicidal ideation is found. Stress management, especially long-term stress assessment and management with a focus on emotional stress should be incorporated into HIV health care in an appropriate manner. In addition, social support should also be continuously provided to this vulnerable population.

Data Availability

The data sets used and analysed in the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Rosenberg ML, Davidson LE, Smith JC, et al. Operational criteria for the determination of suicide. J Forensic Sci. 1988;33(6):1445–56.

Klonsky ED, May AM, Saffer BY. Suicide, Suicide Attempts, and Suicidal Ideation. In: Cannon TD, Widiger T, editors. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, vol. 12. Palo Alto: Annual Reviews; 2016. p. 307–30.

Hubers AAM, Moaddine S, Peersmann SHM, et al. Suicidal ideation and subsequent completed suicide in both psychiatric and non-psychiatric populations: a meta-analysis. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27(2):186–98.

Kang CR, Bang JH, Cho S-I, et al. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults: differences in risk factors and their implications. Aids Care. 2016;28(3):306–13.

Wu YL, Yang HY, Wang J, et al. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and associated factors among HIV-positive MSM in Anhui. China Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(7):496–503.

Li HC, Tucker J, Holroyd E, Zhang J, Jiang BF. Suicidal ideation, resilience, and healthcare implications for newly diagnosed HIV-positive men who have sex with men in China: A qualitative study. Arch Sex Behav. 2017;46(4):1025–34.

Mo PKH, Lau JTF, Wu XB. Relationship between illness representations and mental health among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/Hiv. 2018;30(10):1246–51.

Ferlatte O, Salway T, Oliffe JL, Trussler T. Stigma and suicide among gay and bisexual men living with HIV. Aids Care. 2017;29(11):1346–50.

Wang YY, Dong M, Zhang QE, et al. Suicidality and clinical correlates in Chinese men who have sex with men (MSM) with HIV infection. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24(2):137–43.

Cerwenka S, Brunner F. Sexual identity, sexual attraction and sexual behaviour - dimensions of sexual orientation in survey research. Z Sex Forsch. 2018;31(3):277–94.

Chen GZ, Li Y, Zhang BC, et al. Psychological characteristics in high-risk MSM in China. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:7.

Luo R, Silenzio VMB, Huang Y, Chen X, Luo D. The disparities in mental health between gay and bisexual men following positive HIV diagnosis in China: A one-year follow-up study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(10):3414.

Agnew-Brune CB, Balaji AB, Mustanski B, et al. Mental health, social support, and HIV-related sexual risk behaviors among HIV-negative adolescent sexual minority males: three U.S. cities, 2015. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(12):3419–26.

Bränström R, Pachankis JE. Validating the syndemic threat surrounding sexual minority men’s health in a population-based study with national registry linkage and a heterosexual comparison. J Acquir Immune Defic Synd.r. 2018;78(4):376–82.

Dong MJ, Peng B, Liu ZF, et al. The prevalence of HIV among MSM in China: a large-scale systematic analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):20.

Luo Z, Feng T, Fu H, Yang T. Lifetime prevalence of suicidal ideation among men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis. Bmc Psychiatry. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1575-9.

Martinez J, Lemos D, Hosek S, Adolescent Med Trials N. Stressors and sources of support: the perceptions and experiences of newly diagnosed latino youth living with HIV. Aids Patient Care Stds. 2012;26(5):281–90.

O’Donnell JK, Gaynes BN, Cole SR, et al. Ongoing life stressors and suicidal ideation among HIV-infected adults with depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:322–8.

Garrido-Hernansaiz H, Alonso-Tapia J. Associations among resilience, posttraumatic growth, anxiety, and depression and their prediction from stress in newly diagnosed people living with HIV. Janac J Assoc Nurses Aids Care. 2017;28(2):289–94.

Rukundo GZ, Mishara BL, Kinyanda E. Burden of suicidal ideation and attempt among persons living with HIV and AIDS in Semiurban Uganda. Aids Res Treatment. 2016;2016:2016.

Ophinni Y, Adrian Siste K, et al. Suicidal ideation, psychopathology and associated factors among HIV-infected adults in Indonesia. Bmc Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02918-0.

Rzeszutek M. A longitudinal analysis of posttraumatic growth and affective well-being among people living with HIV: The moderating role of received and provided social support. Plos One. 2018;13(8):e0201641.

Lu HF, Sheng WH, Liao SC, et al. The changes and the predictors of suicide ideation and suicide attempt among HIV-positive patients at 6–12 months post diagnosis: A longitudinal study. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(3):573–84.

Huang YX, Luo D, Chen X, Zhang DX, Huang ZL, Xiao SY. HIV-related stress experienced by newly diagnosed people living with HIV in China: A 1-year longitudinal study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):15.

Kessler RC, Ustün TB. The world mental health (WMH) survey initiative version of the World health organization (WHO) Composite international diagnostic interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):93–121.

Ophinni Y, Adrian Siste K, et al. Suicidal ideation, psychopathology and associated factors among HIV-infected adults in Indonesia. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):255.

Mu H, Li Y, Liu L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for lifetime suicide ideation, plan and attempt in Chinese men who have sex with men. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:117.

Liu Y, Niu L, Wang M, Chen X, Xiao S, Luo D. Suicidal behaviors among newly diagnosed people living with HIV in Changsha China. AIDS Care. 2017;29(11):1359–63.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Patient Health Questionnaire P. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD - The PHQ primary care study. JAMA-J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282(18):1737–44.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Lowe B. The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psych. 2010;32(4):345–59.

Wang WZ, Bian Q, Zhao Y, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psych. 2014;36(5):539–44.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder - The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7.

He X, Li C, Qian J, Cui H, Wu W. Reliability and validity of a generalized anxiety disorder scale in general hospital outpatients. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2010;22:200–3.

Tong X, An DM, McGonigal A, Park SP, Zhou D. Validation of the generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) among Chinese people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2016;120:31–6.

Niu L, Qiu Y, Luo D, et al. Cross-culture validation of the HIV/AIDS stress scale: the development of a revised chinese version. Plos One. 2016;11(4):e0152990.

Pakenham KI, Rinaldis M. Development of the HIV/AIDS stress scale. Psychol Health. 2002;17(2):203–19.

Xiao SY. The theory basis and application of the social support rating scale. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;4:98–100.

Zorn CJW. Generalized estimating equation models for correlated data: A review with applications. Am J Pol Sci. 2001;45(2):470–90.

Mu HJ, Li YX, Liu L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for lifetime suicide ideation, plan and attempt in Chinese men who have sex with men. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:10.

Murphy PJ, Hevey D. The relationship between internalised HIV-related stigma and posttraumatic growth. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1809–18.

Radcliffe J, Fleisher CL, Hawkins LA, et al. Posttraumatic stress and trauma history in adolescents and young adults with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(7):501–8.

Theuninck AC, Lake N, Gibson S. HIV-related posttraumatic stress disorder: investigating the traumatic events. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(8):485–91.

Rzeszutek M, Gruszczynska E. Posttraumatic growth among people living with HIV: A systematic review. J Psychosomat Res. 2018;114:81–91.

Bellini M, Bruschi C. HIV infection and suicidality. J Affect Disord. 1996;38(2–3):153–64.

Dekel S, Ein-Dor T, Solomon Z. Posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic distress: a longitudinal study. Psychol Trauma. 2012;4(1):94–101.

Herek GM. AIDS and stigma. Am Behav Sci. 1999;42(7):1106–16.

Smit PJ, Brady M, Carter M, et al. HIV-related stigma within communities of gay men: A literature review. Aids Care. 2012;24(4):405–12.

Liu JX, Choi K. Experiences of social discrimination among men who have sex with men in Shanghai China. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:S25–33.

Pereira H, Caldeira D, Monteiro S. Perceptions of HIV-related stigma in Portugal among MSM with HIV infection and an undetectable viral load. Janac J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2018;29(3):439–53.

Flowers P, Duncan B, Frankis J. Community, responsibility and culpability: HIV risk-management amongst Scottish gay men. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;10(4):285–300.

Wu Y, Sun Y, Zhang X, Zhang Z, Cao H. Study on the social psychology influencing factors of suicidal ideation in people living with AIDS. Chin J Dis Control Prevent. 2007;4:342–5.

Qu W, Tian J, Keyi X, Wang K. The study of the cause of suicide among people living with HIV/AIDS and crisis intervention. Chin J AIDS STD. 2005;2:91–3.

Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–97.

Elenga N, Georger-Sow M-T, Messiaen T, et al. Incidence and predictive factors of depression among patients with HIV infection in Guadeloupe: 1988–2009. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(8):559–63.

Celesia BM, Nigro L, Pinzone MR, et al. High prevalence of undiagnosed anxiety symptoms among HIV-positive individuals on cART: a cross-sectional study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17(15):2040–6.

Williams JMG, Crane C, Barnhofer T, Van der Does AJW, Segal ZV. Recurrence of suicidal ideation across depressive episodes. J Affect Disord. 2006;91(2–3):189–94.

Aina Y, Susman JL. Understanding comorbidity with depression and anxiety disorders. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2006;106(5 Suppl 2):S9-14.

Jin H, Atkinson JH, Yu X, et al. Depression and suicidality in HIV/AIDS in China. J Affect Disord. 2006;94(1–3):269–75.

Bernanke JA, Stanley BH, Oquendo MA. Toward fine-grained phenotyping of suicidal behavior: the role of suicidal subtypes. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(8):1080–1.

Rizk MM, Galfalvy H, Singh T, et al. Toward subtyping of suicidality: Brief suicidal ideation is associated with greater stress response. J Affect Disord. 2018;230:87–92.

Mao Y, Qiao S, Li X, Zhao Q, Zhou Y, Shen Z. Depression, social support, and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV in Guangxi, china: a longitudinal study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2019;31(1):38–50.

Isay RA. Heterosexually married homosexual men: clinical and developmental issues. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(3):424–32.

Zhang B, Li X, Hu T, Shi T, Liu D. HIV/AIDS interventions targeting men who have sex with men (MSM): theory and practice. Chin J AIDS STD. 2000;3:155–7.

Keiser O, Spoerri A, Brinkhof MWG, et al. Suicide in HIV-Infected Individuals and the General Population in Switzerland, 1988–2008. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):143–50.

Arendt G, de Nocker D, von Giesen H-J, Nolting T. Neuropsychiatric side effects of efavirenz therapy. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2007;6(2):147–54.

Shubber Z, Mills EJ, Nachega JB, et al. Patient-reported barriers to adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos Med. 2016;13(11):e1002183.

Sherr L, Lampe F, Norwood S, et al. Successive switching of antiretroviral therapy is associated with high psychological and physical burden. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(10):700–4.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express gratitude to the staff of Changsha Infectious Disease Hospital and the Changsha Center for Disease Control and Prevention, for their kindest contributions and assistance to this study. We also acknowledge Miss Fengying Bi and Dongqin Yan (Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University) for their assistance with data collection.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2019JJ40401) the Development and Reform Commission of Hunan Province ([2019]875), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81202290).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DL conceived and designed the study, was responsible for study coordination and drafted the main content of the manuscript. RL contributed to drafting the manuscript and analyzing the data. XC assisted in reviewing protocol, study coordination in the field, and reviewing the manuscript. VS and YH critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and made the main revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Ethical Approval

The independent ethics committee (IEC) of the Institute of Clinical Pharmacology at Central South University (CTXY-120033–3) approved the baseline and first follow-up study. The IEC of the Xiangya School of Public Health, Central South University (XYGW-2018–055) approved the second follow-up study.

Consent to Participate

All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, R., Silenzio, V.M.B., Huang, Y. et al. The Changes and the Predictors of Suicidal Ideation Among HIV-positive Sexual Minority Men: A Five-year Longitudinal Study from China. AIDS Behav 26, 339–349 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03387-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03387-6