Abstract

Contradictory data have been reported concerning neuropsychiatric side effects of the first-line antiretroviral drug dolutegravir, which may be partly due to lack of control groups or psychiatric assessment tools. Using validated self-report questionnaires, we compared mood and anxiety (DASS-42), impulsivity (BIS-11), and substance use (MATE-Q) between dolutegravir-treated and dolutegravir-naive people living with HIV (PLHIV). We analyzed 194, mostly male, PLHIV on long-term treatment of whom 82/194 (42.3%) used dolutegravir for a median (IQR) of 280 (258) days. Overall, 51/194 (26.3%) participants reported DASS-42 scores above the normal cut-off, 27/194 (13.5%) were classified as highly impulsive, and 58/194 (29.9%) regularly used recreational drugs. Regular substance use was positively associated with depression (p = 0.012) and stress scores (p = 0.045). We observed no differences between dolutegravir-treated and dolutegravir-naive PLHIV. Our data show that depressed and anxious moods and impulsivity are common in PLHIV and associate with substance use and not with dolutegravir use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

All recent national and international guidelines include the integrase inhibitor (INSTI) dolutegravir (DTG) in the list of first-line antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) for people living with HIV (PLHIV) [1]. DTG has an excellent efficacy, limited drug-drug interactions, a high genetic barrier to resistance and is generally well tolerated [2]. Moreover, generic versions became available for low-and middle income countries with a median price of as low as $75 per year [3]. Contradictory findings have been reported concerning neuropsychiatric side effects of DTG. While early randomized trials reported low discontinuation rates due to side effects among DTG-treated individuals (2–4%) [4,5,6,7,8], several recent observational studies showed rates up to 15% [9,10,11,12,13]. The majority of these side effects involved neuropsychiatric symptoms, including insomnia and depressive symptoms. Data on the prevalence and nature of the neuropsychiatric side effects, as well as associated risk factors (e.g. female sex, older age or concomitant use of the ARV drug abacavir [ABC] [10]) are limited. In addition, it remains unclear whether these neuropsychiatric symptoms are specific for DTG or represent an INSTI class effect [14]. Most currently available studies lacked psychiatric assessment tools or proper control groups and often relied on spontaneous recording of side effects in medical records. In addition, many did not take possible confounders, such as recreational drug use, into account. As mental health and adherence are critical for successful cART, more data on the tolerability of DTG and other INSTI are needed. Using validated psychiatric assessment tools, we compared mood, impulsivity, and recreational substance use between DTG-treated and DTG-naive individuals, as well as between INSTI-treated and non-INSTI treated individuals.

Methods

This cross-sectional observational study is part of the 200HIV Human Functional Genomics Project (HFGP), which focuses on interactions between genetic variations, microbial communities and phenotypic variation, including mental health (www.humanfunctionalgenomics.org) [15]. The Medical Ethical Review Committee Arnhem-Nijmegen (Ref. 2012–550) approved the study protocol and all participants provided written informed consent. Between December 2015 and February 2017, a consecutive series of PLHIV from the HIV-clinic of Radboud university medical center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands were asked to participate in our study. Caucasian individuals aged ≥ 18 years, on cART ≥ 6 months with HIV-RNA load ≤ 200 copies/mL and without active hepatitis B/C or signs of acute infections, were considered eligible. Here, we analyzed all DTG-treated individuals and DTG-naive individuals from the HFGP. Eight participants were excluded because of prior discontinuation of DTG. These individuals did not differ from the DTG-treated individuals in age, sex, CD4 nadir, or scores on the self-report questionnaires. DTG had been discontinued after a median (IQR) of 111(350) days. In 7/8 (87.5%) patients, possible side effects leading to discontinuation were recorded (multiple reasons could be recorded per patient): sleep disturbances (n = 2), psychiatric symptoms (n = 2), headache (n = 3), fatigue (n = 2), dizziness (n = 1), gastro-intestinal complaints (n = 1), and itch (n = 1).

Socio-demographic information and information on health status were collected using an extensive questionnaire, including questions on recently experienced concentration disturbances and headache complaints. Clinical data were extracted from clinical files.

Mood disorders, anxiety, and substance use are among the most commonly reported psychiatric diagnoses in PLHIV [16]. In addition, we and others observed high levels of impulsivity, translating into risk behavior PLHIV [17,18,19]. We selected golden standard questionnaires focused on mood and anxiety, impulsivity, and substance use meeting the following conditions: 1. self-reporting 2. available in Dutch 3. maximum length of ten minutes 4. validated in healthy and patient populations. The 42-item version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-42 (DASS-42) measures levels of depression, anxiety and stress, with higher scores indicating higher symptom levels. The DASS-42 has a high internal consistency and reliability, and has been validated in Dutch populations [20, 21]. The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 (BIS-11) assesses overall impulsivity and three subscales – attention, motor and non-planning. Higher scores indicate greater impulsivity [22]. The Dutch version of the BIS-11 has been validated in normal and clinical samples [23]. We used the substance use module of the Dutch version of the Measurements in the Addictions for Triage and Evaluation Questionnaire (MATE-Q), which assesses psychoactive substance use, both in the recent past (≤ 30 days prior study visit) and in lifetime [24]. The MATE-Q is based on the WHO’s Composed International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, version 2.1) and has been validated in Dutch populations [25].

We conducted a post-hoc power analysis for multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with three dependent variables (DASS-42 or BIS-11 subscales) and two groups (DTG vs. DTG-naive) in G*POWER [26]. The available total sample size of 194 allowed detection of a DTG-effect of f2 = 0.06 (considered small-medium) [27], with 80% power and α = 0.05. Comparisons of general characteristics between DTG and DTG-naive individuals were made using Student’s T-test (or Mann–Whitney U) for continuous variables and χ2 (or Fisher’s exact) for categorical variables. Differences in DASS-42 and BIS-11 scores between DTG and DTG-naive were analyzed using MANCOVA. In case of missing values of < 15%, values were imputed by pooling the scores of the affected subscale(s). Logistic regression analyses were performed for dichotomous data (regular substance use and DASS-42 or BIS-11 scores above the normal cut-off). Spearman’s correlations were applied to explore associations between substance use, and DASS-42 and BIS-11 scores. Additional MANCOVAs were performed to compare DTG with other INSTI (elvitegravir and raltegravir), INSTI with non-INSTI, and DTG-ABC with DTG-non-ABC. Subgroup analyses were performed for older individuals (age ≥ 55 years), females, and those on non-efavirenz cART (given efavirenz’ association with neuropsychiatric symptoms) [28]. Age, nadir CD4+ cell count, and duration of HIV infection were included as covariates in the adjusted models. To avoid inflating the risk of Type 1 errors, only adjusted MANCOVAs with p < 0.05 were followed by univariate analyses (with Bonferroni correction). A two-tailed p of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS (SPSS 24, Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

After exclusion of eight individuals with missing values of ≥ 15% in the DASS-42 or BIS-11, we analyzed 194 individuals of whom 82/194 (42.3%) used DTG-containing cART (Fig. S1 Study Flowchart, electronic supplementary material). Study participants had a median (IQR) age of 52.5 (13.3) years and the majority (176/194 [90.7%]) were male. DTG-treated individuals were slightly younger compared to DTG-naive individuals (p = 0.013) and had a shorter duration of HIV infection (p = 0.0024) and cART (p = 0.0015; Table 1). The median (IQR) duration of DTG treatment was 280 (258) days. DTG was combined with ABC in 59/82 (72.0%) individuals, with emtricitabine-tenofovir in 13/82 (15.9%), with boosted atazanavir or darunavir in 8/82 (9.8%), and as dual therapy with lamivudine in 2/82 (2.4%).

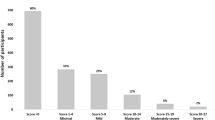

Psychiatric symptoms were common in our population. Overall, 51/194 (26.3%) individuals scored above the normal cut-off for depression, anxiety or stress (DASS-42), and 27/194 (13.9%) individuals were classified as highly impulsive (BIS-11 total score ≥ 72) [23]. Scores did not significantly differ between DTG-treated and DTG-naive individuals, after adjustment for age, nadir CD4 + cell count, and duration of HIV infection. Similarly, we observed no differences when comparing DTG (n = 82) with other INSTIs (raltegravir and elvitegravir, n = 49), or INSTIs (n = 132) with non-INSTIs (n = 62) (see Table 2 and Tables S1-S3, electronic supplementary material, for [M]ANCOVAs and neuropsychiatric scores for the different ARV classes). Limiting our analysis to females (n = 5 for DTG and n = 11 for DTG-naive) did not change these results. In individuals aged ≥ 55 years, BIS-11 scores differed significantly between individuals on DTG (n = 27) and non-DTG regimens (n = 53, F(3,73) = 2.8, p = 0.047, ηp2 = 0.10), with lower non-planning impulsivity scores in those on DTG (adjusted mean difference [95%CI] = -− 3.16 (− 5.51 to − 0.8), p = 0.0093). After exclusion of individuals on efavirenz (n = 1 for DTG and n = 16 for DTG-naive), we observed a marginal group difference in BIS-11 scores (F(3,170) = 2.7, p = 0.045, ηp2 = 0.05), driven by higher motor impulsivity scores in the DTG group (adjusted mean difference [95%CI] = 1.17 [0.13 to 2.22], p = 0.027). Within the DTG group, individuals on ABC (n = 59) had lower DASS-42 scores compared to those on alternative backbones (n = 23, F(3,75) = 4.6, p = 0.0052, ηp2 = 0.16). Post-hoc analyses showed significantly lower scores for anxiety (adjusted mean difference [95%CI] = -− 3.96 [− 6.16 to − 1.76], p = 0.00060), and a trend for lower stress scores (adjusted mean difference [95%CI] = -− .81 [− 6.15 to 0.52], p = 0.097) in individuals on DTG-ABC combinations.

In addition to symptoms of mood and impulsivity, we evaluated the frequency of substance use in our study sample. Regular substance use was defined as use of any psychoactive substance (with the exception of alcohol and tobacco) during periods ≥ 1 time per week including ≥ 1 time during the 30 days prior to the study visit. A high proportion of the participants regularly used recreational drugs (58/194 [29.9%]), with cannabis, γ-Hydroxybutyric acid (GHB), and alkyl nitrites (“poppers”) as the most commonly used agents. We observed significant positive associations between regular substance use and depression (p = 0.012) and stress scores (p = 0.045), and a trend with attentional impulsivity scores (p = 0.092) (Table 3). Substance use did not differ between treatment groups (Table 2), nor did it confound our primary analyses (Table S4, Electronic supplementary material for adjusted MANCOVAs with and without substance use). Finally, we found no differences in self-reported headache complaints and concentration disturbances (Table 1).

Discussion

In the present study, we found a high frequency of depressed and anxious moods and impulsivity in long-term treated PLHIV, which was associated with regular substance use and not with DTG use. Similarly, we observed no differences when comparing DTG with other INSTIs, and INSTIs with non-INSTIs. Our findings are in line with data from clinical trials, which reported relatively few DTG-related neuropsychiatric side effects. Moreover, studies show improvement of neuropsychiatric symptoms after substituting efavirenz for DTG [29,30,31] and a recent meta-analysis showed no increased risk for suicidality among DTG-treated individuals [32]. However, our findings are in contrast with observational studies, which predominantly focused on individuals who discontinued DTG or other INSTIs. These individuals commonly reported neuropsychiatric symptoms at time of switch [10, 33,34,35]. In our cohort, a minority of individuals (9% of ever DTG users) had discontinued DTG before, with a very small portion (3% of ever DTG users) potentially related to neuropsychiatric side effects. Our data support that DTG is well tolerated by most individuals. The occurrence of neuropsychiatric side effects in a small subset of DTG-treated individuals, however, cannot be ruled out.

Mechanistically, DTG penetrates the blood brain barrier and may inhibit organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2), which is involved in the transport of serotonin and dopamine [36, 37]. While one study indeed showed that DTG-treated individuals with a genetic variant of the gene encoding for the OCT2 (SLC22A2 C > A) were at higher risk of having abnormal scores of the Symptom Checklist (SCL)-90-R [37], the lack of a control group of DTG-naive PLHIV limits causal inference. Several risk factors have been proposed for DTG-related neuropsychiatric side effects, including older age [11, 34, 38,39,40,41], female sex [9, 40, 41], and a backbone containing ABC [9, 33, 41, 42]. In our study, separate analyses in older individuals and females showed similar results, though the latter should be interpreted with caution given the small sample of females. Interestingly, we observed lower rather than higher levels of mood symptoms in individuals on DTG-ABC combinations. This may be caused by channeling due to certain patient characteristics, e.g. by prescribing TDF-containing backbones to PLHIV with cardiovascular disease or hepatitis B, conditions that have also been associated with an increased prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms [43, 44]. Still, our observations are in line with several other studies reporting no associations between DTG-ABC use and neuropsychiatric symptoms [11, 40]. In addition, no differences in DTG plasma trough concentrations were found between patients on ABC, rilpivirine, or darunavir [45, 46]. Together, these findings argue against a previously suggested DTG-ABC pharmacokinetic amplification of side effects. Finally, efavirenz co-treatment, which was most prevalent in the DTG-naive group, did not seem to obscure group differences in mood symptoms.

The currently available real life studies on DTG-related neuropsychiatric side effects often relied on spontaneous recordings of psychiatric symptoms in patient files in retrospective designs. The application of standardized validated psychiatric assessment tools is a major strength of the current study, increasing reliability and validity. Using comparable questionnaires, we and others previously observed unexpectedly high levels of neuropsychiatric symptoms among individuals on long-term efavirenz [47,48,49]. Absence of high symptom levels in individuals on DTG-containing regimens, when applying similar methodology in a sample that was sufficiently powered for detection of small-medium effects, strongly argues against such a phenomenon in DTG.

Another strength of our study is that, by selecting individuals on long-term cART with suppressed viral loads and no acute infections, we reduced the chance of potential HIV-related confounders. Our study has several limitations. First, our study was not primarily designed to assess adverse effects of DTG and we did not examine participants before and after initiation of DTG. Second, we cannot rule out that our study population may have consisted of a selection of people more tolerant to DTG as we excluded individuals who previously discontinued DTG from our analyses. Third, while we used validated questionnaires to assess mood and impulsivity, we did not employ a gold-standard instrument for examining drug-induced neuropsychiatric symptoms in general (including sleep disturbances), like the Scandinavian Society of Psychopharmacology UKU Rating Scale [50]. Fourth, we have limited data on females and non-Caucasian individuals and future research should confirm the tolerability of DTG and generalizability of our findings to these populations.

Despite these drawbacks, we believe that our data, obtained from a sufficiently large patient sample using validated psychiatric tools, supports the safety of dolutegravir in the majority of PLHIV. Still, psychiatric symptoms were common in our population, with scores above the normal cut-off in 26.3% and 13.9% on the DASS-42 and BIS-11 respectively. While these cannot be accounted for by DTG, other factors are likely to contribute. For example, traumatic experiences, stigma, and substance use disorders have been shown to contribute to high levels of mental health problems in PLHIV [51, 52]. Indeed, we found significant associations between regular substance use and depression and stress scores. By working synergistically in promoting behaviors that impede treatment adherence, substance use and depression may also lead to cART discontinuation [53, 54].

Our study highlights the need for proactive screening of mental health problems and substance use in PLHIV, and subsequent referral for adequate psychiatric care if needed. Finally, future studies on neuropsychiatric side effects of ARVs should not only use validated instruments, but also integrate host and lifestyle factors such as substance use.

Data availability

All data were deposited into the publicly accessible DANS EASY archive (URL is being generated and will follow; until then all data are available from the corresponding author upon request).

References

WHO. Updated recommendations on first-line and second-line antiretroviral regimes and post-exposure prophylaxis and recommendations on early infant diagnosis of HIV. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Available from: www.who.int/hiv.

Vitoria M, Hill A, Ford N, Doherty M, Clayden P, Venter F, et al. The transition to dolutegravir and other new antiretrovirals in low- and middle-income countries - what are the issues? AIDS. 2018.

UNITAID. New high-quality antiretroviral therapy to be launched in South Africa, Kenya and over 90 low- and middle-income countries at reduced price2017 1 March 2019. Available from: https://unitaid.org/news-blog/new-high-quality-antiretroviral-therapy-launched-south-africa-kenya-90-low-middle-income-countries-reduced-price/#en.

Fettiplace A, Stainsby C, Winston A, Givens N, Puccini S, Vannappagari V, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in patients receiving dolutegravir. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(4):423–31.

Raffi F, Jaeger H, Quiros-Roldan E, Albrecht H, Belonosova E, Gatell JM, et al. Once-daily dolutegravir versus twice-daily raltegravir in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection (SPRING-2 study): 96 week results from a randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(11):927–35.

Walmsley SL, Antela A, Clumeck N, Duiculescu D, Eberhard A, Gutierrez F, et al. Dolutegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(19):1807–18.

Clotet B, Feinberg J, van Lunzen J, Khuong-Josses MA, Antinori A, Dumitru I, et al. Once-daily dolutegravir versus darunavir plus ritonavir in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection (FLAMINGO): 48 week results from the randomised open-label phase 3b study. Lancet. 2014;383(9936):2222–31.

Orrell C, Hagins DP, Belonosova E, Porteiro N, Walmsley S, Falco V, et al. Fixed-dose combination dolutegravir, abacavir, and lamivudine versus ritonavir-boosted atazanavir plus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine in previously untreated women with HIV-1 infection (ARIA): week 48 results from a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3b study. Lancet HIV. 2017.

Elzi L, Erb S, Furrer H, Cavassini M, Calmy A, Vernazza P, et al. Adverse events of raltegravir and dolutegravir. AIDS. 2017;31(13):1853–8.

de Boer MG, van den Berk GE, van Holten N, Oryszcyn JE, Dorama W, Moha DA, et al. Intolerance of dolutegravir-containing combination antiretroviral therapy regimens in real-life clinical practice. AIDS. 2016;30(18):2831–4.

Menard A, Montagnac C, Solas C, Meddeb L, Dhiver C, Tomei C, et al. Neuropsychiatric adverse effects on dolutegravir: an emerging concern in Europe. AIDS. 2017;31(8):1201–3.

Penafiel J, de Lazzari E, Padilla M, Rojas J, Gonzalez-Cordon A, Blanco JL, et al. Tolerability of integrase inhibitors in a real-life setting. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(6):1752–9.

Rossetti B, Baldin G, Sterrantino G, Rusconi S, De Vito A, Giacometti A, et al. Efficacy and safety of dolutegravir-based regimens in advanced HIV-infected naïve patients: results from a multicenter cohort study. Antiviral Res. 2019;169:104552.

Kheloufi F, Boucherie Q, Blin O, Micallef J (2017) Neuropsychiatric events and dolutegravir in HIV patients a worldwide issue involving a class effect. AIDS. 31: 1775-1777

Netea MG, Joosten LA, Li Y, Kumar V, Oosting M, Smeekens S, et al. Understanding human immune function using the resources from the Human Functional Genomics Project. Nat Med. 2016;22(8):831–3.

Gaynes BN, Pence BW, Eron JJ Jr, Miller WC. Prevalence and comorbidity of psychiatric diagnoses based on reference standard in an HIV+ patient population. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(4):505–11.

Arends RM, Nelwan EJ, Soediro R, van Crevel R, Alisjahbana B, Pohan HT, et al. Associations between impulsivity, risk behavior and HIV, HBV, HCV and syphilis seroprevalence among female prisoners in Indonesia: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0207970.

Arends RM, van den Heuvel TJ, Foeken-Verwoert EGJ, Grintjes KJT, Keizer HJG, Schene AH, et al. Sex, drugs, and impulse regulation: A perspective on reducing transmission risk behavior and improving mental health among MSM living With HIV. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1005.

Margolin A, Schuman-Olivier Z, Beitel M, Arnold RM, Fulwiler CE, Avants SK. A preliminary study of spiritual self-schema (3-S(+)) therapy for reducing impulsivity in HIV-positive drug users. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(10):979–99.

Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Korotitsch W, Barlow DH. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(1):79–89.

de Beurs E, Van Dyck R, Marquenie LA, Lange A, Blonk RW. De DASS: een vragenlijst voor het meten van depressie, angst en stress. Gedragstherapie. 2001;51:768–74.

Lindstrom JC, Wyller NG, Halvorsen MM, Hartberg S, Lundqvist C. Psychometric properties of a Norwegian adaption of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11 in a sample of Parkinson patients, headache patients, and controls. Brain and behavior. 2017;7(1):e00605.

Stanford MS, Mathias CW, Dougherty DM, Lake SL, Anderson NE, Patton JH. Fifty years of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale: An update and review. Pers Indiv Differ. 2009;47(5):385–95.

Schippers GM, Broekman TG, Buchholz A, Koeter MW, van den Brink W. Measurements in the Addictions for Triage and Evaluation (MATE): an instrument based on the World Health Organization family of international classifications. Addiction. 2010;105(5):862–71.

Schippers GM, Broekman TG, Bucholz A. MATE 2.0. Handleiding en protocol. Nijmegen: Betaboeken; 2007.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–91.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988.

Apostolova N, Funes HA, Blas-Garcia A, Galindo MJ, Alvarez A, Esplugues JV. Efavirenz and the CNS: what we already know and questions that need to be answered. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(10):2693–708.

Bracchi M, Boffito M, Nelson M, Adams T, Clarke A, Waters L, et al. Multicentre open-label, pilot study of switching from efavirenz to dolutegravir for central nervous system (CNS) toxicity-interim analysis results. HIV Med. 2016;17:20.

Keegan MR, Winston A, Higgs C, Fuchs D, Boasso A, Nelson M. Tryptophan metabolism and its relationship with central nervous system toxicity in people living with HIV switching from efavirenz to dolutegravir. Journal of neurovirology. 2018.

Asundi A, Robles Y, Starr T, Landay A, Kinslow J, Ladner J, et al. Immunological and neurometabolite changes associated with switch from efavirenz to an integrase inhibitor. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81(5):585–93.

Hill AM, Mitchell N, Hughes S, Pozniak AL. Risks of cardiovascular or central nervous system adverse events and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, for dolutegravir versus other antiretrovirals: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2018;13(2):102–11.

Cailhol J, Rouyer C, Alloui C, Jeantils V. Dolutegravir and neuropsychiatric adverse events: a continuing debate. AIDS. 2017;31(14):2023–4.

Bonfanti P, Madeddu G, Gulminetti R, Squillace N, Orofino G, Vitiello P, et al. Discontinuation of treatment and adverse events in an Italian cohort of patients on dolutegravir. AIDS. 2017;31(3):455–7.

Borghetti A, Baldin G, Capetti A, Sterrantino G, Rusconi S, Latini A, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of dolutegravir and two nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors in HIV-1-positive, virologically suppressed patients. AIDS. 2017;31(3):457–9.

Gele T, Furlan V, Taburet AM, Pallier C, Becker PH, Goujard C, et al. Dolutegravir Cerebrospinal Fluid Diffusion in HIV-1-Infected Patients with Central Nervous System Impairment. Open forum infectious diseases. 2019; 6(6):174.

Borghetti A, Calcagno A, Lombardi F, Cusato J, Belmonti S, D'Avolio A, et al. SLC22A2 variants and dolutegravir levels correlate with psychiatric symptoms in persons with HIV. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2018.

Penafiel J, de Lazzari E, Padilla M, Rojas J, Gonzalez-Cordon A, Blanco JL, et al. Tolerability of integrase inhibitors in a real-life setting. J Antimicrob Chemoth. 2017;72(6):1752–9.

Kirby C, Ovens K, Shaw M, Hardweir V, Gilleece Y, Churchill D. Adverse events of dolutegravir may be higher in real world settings. HIV Med. 2016;17:22–3.

Capetti AF, Di Giambenedetto S, Latini A, Sterrantino G, De Benedetto I, Cossu MV, et al. Morning dosing for dolutegravir-related insomnia and sleep disorders. HIV medicine. 2017.

Hoffmann C, Welz T, Sabranski M, Kolb M, Wolf E, Stellbrink HJ, et al. Higher rates of neuropsychiatric adverse events leading to dolutegravir discontinuation in women and older patients. HIV Med. 2017;18(1):56–63.

Borghetti A, Baldin G, Capetti A, Sterrantino G, Rusconi S, Latini A, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of dolutegravir and two nucleos(t) ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors in HIV-1-positive, virologically suppressed patients. AIDS. 2017;31(3):457–9.

de Boer MGJ, Brinkman K. Recent observations on intolerance of dolutegravir: differential causes and consequences. AIDS. 2017;31(6):868–70.

Ozkan M, Corapcioglu A, Balcioglu I, Ertekin E, Khan S, Ozdemir S, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and its effect on the quality of life of patients with chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(3):283–97.

Hare DL, Toukhsati SR, Johansson P, Jaarsma T. Depression and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(21):1365–72.

Cattaneo D, Minisci D, Cozzi V, Riva A, Meraviglia P, Clementi E, et al. Dolutegravir plasma concentrations according to companion antiretroviral drug: unwanted drug interaction or desirable boosting effect? J Int Aids Soc. 2016;19.

Alcantarini C, Calcagno A, Marinaro L, Ferrara M, Milesi M, Trentalange A, et al. Determinants of dolutegravir plasma concentrations in the clinical setting. J Int Aids Soc. 2016;19.

Mothapo KM, Schellekens A, van Crevel R, Keuter M, Grintjes-Huisman K, Koopmans P, et al. Improvement of depression and anxiety after discontinuation of long- term efavirenz treatment. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2015;14(6):811–8.

Fumaz CR, Munoz-Moreno JA, Molto J, Negredo E, Ferrer MJ, Sirera G, et al. Long-term neuropsychiatric disorders on efavirenz-based approaches: quality of life, psychologic issues, and adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38(5):560–5.

Gutierrez F, Navarro A, Padilla S, Anton R, Masia M, Borras J, et al. Prediction of neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with long-term efavirenz therapy, using plasma drug level monitoring. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2005;41(11):1648–53.

Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, Dencker SJ, Elgen K. The Uku side-effect rating-scale - a new comprehensive rating-scale for psychotropic-drugs and a cross-sectional study of side-effects in neuroleptic-treated patients - preface. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1987;76:7–000.

Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376(9738):367–87.

Whetten K, Reif S, Whetten R, Murphy-McMillan LK. Trauma, mental health, distrust, and stigma among HIV-Positive persons: Implications for effective care. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(5):531–8.

Fojo AT, Lesko CR, Calkins KL, Moore RD, McCaul ME, Hutton HE, et al. Do symptoms of depression interact with substance use to affect HIV continuum of care outcomes? AIDS Behav. 2019;23(3):580–91.

Cook JA, Grey DD, Burke-Miller JK, Cohen MH, Vlahov D, Kapadia F, et al. Illicit drug use, depression and their association with highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89(1):74–81.

Acknowledgements

We thank all volunteers from the 200HIV HFGP for participation in the study. We thank the clinicians and nurse practitioners of the HIV clinic of the Radboud university medical center for their help with participant recruitment and Martin Jaeger, Sanne Smeekens and Marije Oosting for their help with participant inclusion. Finally, the authors acknowledge Anna Wisse and Astrid Timmerman for their contribution in data collection and Rogier Donders for his advice on statistical analyses.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from Aidsfonds Netherlands (P-29001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lisa Van de Wijer, Wouter van der Heijden, Mihai Netea, Quirijn de Mast, Arnt Schellekens, and André van der Ven contributed to the study design and methodology. Data acquisition was performed by Lisa Van de Wijer and Wouter van der Heijden. Data analysis and interpretation was done by Lisa Van de Wijer, Mike van Verseveld, and Arnt Schellekens. Manuscript originally drafted by Lisa Van de Wijer, with all authors contributing to final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Mihai Netea was supported by an ERC Advanced Grant (833247) and a Spinoza grant of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research. Quirijn de Mast, André van der Ven, and Mihai Netea receive research support from ViiV Healthcare.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. The Medical Ethical Review Committee Arnhem-Nijmegen (Ref. 2012-550) approved the study protocol.

Consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van de Wijer, L., van der Heijden, W., van Verseveld, M. et al. Substance use, Unlike Dolutegravir, is Associated with Mood Symptoms in People Living with HIV. AIDS Behav 25, 4094–4101 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03272-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03272-2