Abstract

This study aimed to identify alcohol use patterns associated with viral non-suppression among women living with HIV (WLWH) and the extent to which adherence mediated these relationships. Baseline data on covariates, alcohol consumption, ART adherence, and viral load were collected from 608 WLWH on ART living in the Western Cape, South Africa. We defined three consumption patterns: no/light drinking (drinking ≤ 1/week and ≤ 4 drinks/occasion), occasional heavy episodic drinking (HED) (drinking > 1 and ≤ 2/week and ≥ 5 drinks/occasion) and frequent HED (drinking ≥ 3 times/week and ≥ 5 drinks/occasion). In multivariable analyses, occasional HED (OR 3.07, 95% CI 1.78–5.30) and frequent HED (OR 7.11, 95% CI 4.24–11.92) were associated with suboptimal adherence. Frequent HED was associated with viral non-suppression (OR 2.08, 95% CI 1.30–3.28). Suboptimal adherence partially mediated the relationship between frequent HED and viral non-suppression. Findings suggest a direct relationship between frequency of HED and viral suppression. Given the mediating effects of adherence on this relationship, alcohol interventions should be tailored to frequency of HED while also addressing adherence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite the scale up of evidence-based HIV treatment, South African women continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV—comprising about 60% of the estimated 7.9 million South Africans living with HIV [1]. Although access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) has dramatically reduced HIV morbidity and mortality [2, 3], only about 69% of South African adult women living with HIV (WLWH) are virally suppressed [1]. As viral non-suppression increases the likelihood of rapid disease progression and onward transmission to sexual partners [4, 5], strategies are needed to improve rates of viral suppression among WLWH in South Africa [1].

South Africa, a low-and-middle income country (LMIC) at the southern tip of Africa, is known for its high volume of per capita alcohol consumption amongst people who drink. Although a substantial proportion (> 50%) of the adult population abstain from using alcohol, heavy episodic drinking (HED) is the normative pattern of alcohol use amongst people who drink [6, 7]. HED is sometimes referred to as binge drinking and is typically defined as the consumption of five or more standard drinks or 60 g of absolute alcohol during a single occasion [7]. Similar patterns of alcohol use have been reported amongst people on ART- South African studies estimate that 40% to 63% of PLWH on ART who drink do so at hazardous or harmful levels [8,9,10,11]. Comparable rates of HED have been reported for women on ART, ranging between 30 and 75% of current drinkers [8,9,10]. These patterns of alcohol consumption are of grave concern given evidence from systematic reviews that high levels of alcohol consumption are associated with poorer engagement and retention in HIV care and lower rates of ART adherence for PLWH in both high income countries [12, 13] and in LMICs within sub-Saharan Africa [14]. While some studies also report associations between alcohol use and viral non-suppression, the nature of the relationship between alcohol use and viral suppression requires further clarification [15, 16].

Prior studies examining the relationship between alcohol consumption and viral suppression have produced inconsistent results. Some studies found no association between alcohol use and viral suppression after controlling for self-reported ART adherence, suggesting an indirect relationship with viral suppression explained by alcohol’s association with adherence [17,18,19]. Other studies have reported associations between alcohol use and viral suppression after controlling for adherence [20,21,22,23]. This raises the possibility of alternative, possibly biological pathways through which alcohol may impact response to HIV treatment. Further, only two studies used mediation analysis to examine these relationships which limits our understanding of the importance of the adherence pathway relative to other potential pathways. These studies produced conflicting results: one reported direct effects of alcohol use on viral suppression and indirect effects via adherence [23], whereas the other only found indirect effects through adherence [20]. Both these studies were conducted in the US. Additional research is needed to examine whether findings from these studies can translate to South Africa where the prevalence of HIV is greater, the degree of epidemiological control is poorer, and where risk is generalized rather than concentrated among racial and sexual minorities [1, 4]. In addition, participants in these two studies were predominantly male. As research has demonstrated sex differences in physiological responses to alcohol [24], the extent to which alcohol’s association with viral suppression is mediated by adherence for WLWH requires clarification [16, 17, 25].

Measurement imprecision may explain some of these inconsistent findings. Studies have used a wide range of alcohol consumption measures (quantity only, alcohol use screening tools, frequency only), making it difficult to compare findings across studies [23, 26]. In addition, most prior studies did not examine how specific patterns of drinking relate differently to viral suppression. An exception has been Cook et al. [23] who specified patterns of drinking characterised by different degrees of frequency and quantity, noting that frequent heavy drinking impacted on viral suppression, but not other patterns of drinking marked by occasional heavy drinking, light drinking, or abstinence. However, there is relatively little information on how these alcohol consumption patterns are associated with viral suppression among WLWH, and the extent to which this relationship is mediated by ART adherence [25].

Addressing this information gap is important for the design of interventions aimed at improving rates of viral suppression among WLWH, such as the South African Medical Research Council’s Social Impact Bond for Adolescent Girls and Young Women [27]. If alcohol consumption patterns characterized by abstinence or light drinking are associated with greater likelihood of ART adherence and viral suppression, then interventions that promote abstinence or very limited use of alcohol may be indicated. Furthermore, evidence that certain drinking patterns infer greater risk for poor adherence and viral suppression could identify WLWH who may benefit most from these interventions. If findings show that adherence fully mediates the relationship between drinking and viral suppression, interventions focused on identifying and reducing barriers to adherence during periods of alcohol use would be needed. In contrast, if findings show that adherence only partially mediates alcohol’s association with viral suppression, interventions that focus on reducing alcohol use and facilitating ART adherence would be required.

This paper aims to provide this information by examining (i) the associations between a range of alcohol consumption patterns and HIV viral suppression and (ii) the extent to which these associations are mediated by differences in adherence to ART among a cohort of women obtaining treatment for HIV from primary care clinics in the Western Cape province of South Africa.

Methods

This paper analyses baseline data on women receiving treatment for HIV who participated in Project MIND—a three-arm cluster randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of different resourcing approaches to integrating counselling for unhealthy alcohol use and depression into HIV care (Trial Registration Number: PACTR201610001825403). Trial methods are described in detail elsewhere [27].

Study Setting, Participants, and Procedures

From May 2017 to March 2019, 608 WLWH were recruited from 24 primary care clinics. offering free HIV treatment services to patients from geographically distinct catchment areas. Located in four of the province’s six health districts, 15 of these clinics served urban communities and nine served rural communities [28].

During the recruitment period, HIV care providers asked all patients presenting for routine HIV treatment at these clinics about their recent alcohol use and mood. Individuals reporting alcohol use or low mood were referred to a study assessor for eligibility screening. Patients who were at least 18 years old and taking ART for HIV; obtained an Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test score ≥ 8 (indicating hazardous alcohol use) [10] or a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score ≥ 16 (indicating possible depression) [29] were eligible to participate provided they were not receiving other mental health treatment or participating in another study. Eligible patients who were interested in study participation were enrolled into the study. Recruitment was balanced across these clinics, with participant enrolment continuing until 25 participants (irrespective of gender) meeting eligibility criteria for alcohol and 25 participants meeting eligibility criteria for depression had been enrolled from each clinic.

At the enrolment appointment, an assessor obtained the patient’s written informed consent for trial participation prior to conducting a computer-assisted personal interview in English, Afrikaans. or isiXhosa (the three official languages of the province). Interviews included questions on socio-demographic characteristics, HIV treatment, alcohol use, common mental disorders, and health service use. Participants also provided whole blood samples for HIV viral load testing which were sent to an accredited pathology laboratory for analysis. All study activities occurred in private rooms at the participating clinic.

Measures

HIV Viral Suppression

HIV viral load values were coded into three categories: virally suppressed (< 40 copies/ml); unsuppressed (40–999 copies/ml), and unsuppressed with possible treatment failure (≥ 1000 copies/ml). To ensure adequate power, we re-coded these values into two categories: viral suppression (< 40 copies/ml) and non-suppression (≥ 40 copies/ml).

Patterns of Alcohol Use

To examine frequency of alcohol consumption, participants were asked to recall the number of days they drank alcohol in the month preceding the baseline assessment. Assessors used a calendar to assist participants in recalling days they used alcohol. Using this information, we calculated the average number of drinking days on a typical week. Overall participants drank on average 1.0 days per week in the 30 days preceding the assessment (95% CI 0.8–1.1), but responses were skewed with 43.4% (95% CI 38.7–48.2) of the sample reporting no alcohol consumption over this time. Guided by the distribution of responses and the literature on meaningful categories of weekly drinking frequency [29, 30], we recoded this variable into four categories of weekly drinking frequency: abstinence (n = 264; 43.4% of participants); drinking ≤ 1 day per week (n = 151; 24.8%); drinking > 1 day and ≤ twice per week (n = 100; 16.5%); and drinking ≥ three times per week (n = 93; 15.2%).

Quantity of standard alcoholic drinks consumed on a typical drinking day was assessed by a single questionnaire item, with categorical response options ranging from 0, 1–2 drinks, 3–4 drinks, 5–6 drinks, 7–9 drinks or 10 or more drinks. As we were interested in examining typical patterns of alcohol consumption in the South African context (notably abstinence and HED), we recoded these response options into abstinence (0 drinks), no HED (≥ 1 and < 5 standard drinks typically consumed) and HED (≥ 5 drinks). Although most studies define HED for women as either 40 g or 60 g of absolute alcohol on a single occasion [7, 30], we chose the higher threshold (60 g of absolute alcohol amounts to ≥ five standard drinks) as this is more commonly used in South Africa [6]. To improve participants’ estimations of the number of standard drinks consumed, a challenge in South Africa where people drink a combination of formally and informally produced alcohol [7, 31, 32], participants were shown pictures of frequently consumed alcoholic beverages in this setting.

In an effort to replicate Cook et al.’s [23] approach and allow for meaningful comparisons, and guided by recent literature demonstrating that patterns of alcohol use representing varying frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption have differential effects on health outcomes [30], we used these two indicators to define four past-month alcohol consumption patterns: no drinking (abstainers), light drinking (≤ once per week and ≤ four drinks per occasion reflecting no HED), occasional HED (drinking once or twice a week and ≥ five drinks per occasion) and frequent HED (drinking three or more times per week and ≥ five drinks per occasion). As only 58 women reported light drinking, we combined this with the “no drinking” category. Sensitivity analyses (not reported here) found that combining these categories had little effect on the results.

ART Adherence

ART adherence was assessed by self-report. Self-reported adherence is strongly associated with HIV outcomes and is simpler to obtain than estimates from pill counts or biomarkers [33]. We used the Center for Adherence Support Evaluation (CASE) adherence index [33, 34], a scale that has been widely used in sub-Saharan Africa to measure adherence to ART [34,35,36]. This scale is a composite of three self-reported indicators of adherence, namely: frequency of “difficulty in taking HIV medications on time”, “average number of days per week that at least one dose of HIV medications were missed”, and “last time missed one dose of HIV medications” [34]. Responses on these items are summed to produce a total adherence score ranging from 3 to 16. Higher scores indicate better adherence, with score > 10 indicative of good adherence. Scores > 10 have been shown to correlate with self-reported adherence rates of 95% and viral suppression [34].

Covariates

Covariates included the socio-demographic variables of age (18–30, 31–39, 40–49, ≥ 50 years of age), education (completed high school vs. did not complete high school), relationship status (partner vs. no partner), unemployment, and average monthly income (≤ R2000; R2001–R4000; ≥ R4000; at the time of the study USD 1 ~ ZAR 15). HIV-related covariates included number of years since HIV diagnosis and number of years on ART. Psychosocial covariates included probable depression as assessed by the CES-D where a score of 16 or higher is suggestive of probable depression [28]. Perceived social support was assessed using the 19-item Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Survey, with higher composite scores indicative of more social support [37]. A single item explored any illicit drug use in the past year, with responses coded as yes or no.

Analyses

All analyses were conducted using Stata 16 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA), with significance set at p < 0.05. We used Stata’s survey analysis platform to account for clustering. Using available case analysis to address missing data, a total of 608 observations were included. First, we conducted adjusted Wald test (for categorial variables) and linear regression (for continuous variables) analyses to identify and describe possible relationships between risk factors and the three categories of viral response to ART (suppressed, non-suppressed, non-suppressed with possible treatment failure). We examined the distribution of cases across the three viral load categories for each pattern of alcohol use (none/light, occasional HED, frequent HED). Due to small cell sizes, we dichotomised viral load results into suppressed or non-suppressed categories for all further analyses. Second, we ran logistic regression and adjusted Wald test analyses (for categorial variables) and performed linear regression (for continuous variables) to identify possible relationships between covariates and the hypothesized mediator (adherence) and the exposure of interest (patterns of drinking). Variables associated with drinking patterns and adherence at p < 0.10 were entered in multinomial logistic and multivariable logistic regression models.

Third, we used logistic regression to explore whether the exposure of interest and hypothesised mediator were associated with the outcome of interest. Variables associated with viral suppression at p < 0.10 were entered in a multivariable model. This enabled us to examine the independent effects of adherence and drinking patterns on viral non-suppression while adjusting for potential confounders. We examined possible interactions between age and alcohol consumption patterns use as well as alcohol consumption patterns and adherence in separate regression models.

Finally, we used generalised structural equation modelling (GSEM) to examine the potentially mediating effects of (i) adherence on associations between drinking patterns and viral non-suppression and (ii) drinking patterns on the relationship between age and viral non-suppression while adjusting for other covariates. GSEM allows for the analysis of categorical data using non-linear assumptions for modelling dichotomous data and provides a statistical test of coefficients from mediation analyses [38, 39]. Results are presented graphically, with beta coefficients (b) and standard errors (SE) reported for each path. As GSEM is not able to decompose the total effects into indirect and direct effects for categorical data, we used ldecomp to calculate estimates and confidence intervals of the direct and indirect effects of drinking patterns on viral suppression using bootstrap methods that accounted for clustering [40]. The indirect effect quantifies the portion of the total effect that is mediated by adherence and the direct effect represents the portion of the total effect that is not explained by the mediator.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Most women in the sample were single (71.7%), had not completed high school (87.3%), were unemployed (65.6%), with a monthly income below R2000 (78.0%). Women ranged between 20 and 62 years of age (M = 38.5, SD = 10.0). A quarter of the sample were between 18 and 30 years old. On average, participants had been using ART for five years (M = 5.6, SD = 4.5); 35.7% reported suboptimal adherence. Most participants scored above the cut-off for probable depression (85.0%). Just over half the sample (53.0%) reported no or light drinking in the past month, 32.9% reported occasional HED and 14.1% reported frequent HED. Only 2.6% of the sample reported past year illicit drug use. Viral suppression was achieved by 64.6% of the sample (Table 1). Notably, 110 participants (18.1%) were at risk of treatment failure, of whom 60 had viral loads ≥ 10 000 copies/ml, indicative of high infectiousness. In bivariate analyses, only age (F(6, 10) = 4.87; p = 0.004), ART adherence (F(2, 22) = 7.53; p = 0.003), and patterns of alcohol use (F(4, 20) = 6.86; p = 0.001) were significantly associated with viral load categories (Table 1).

Covariates Associated with the Exposure of Interest and Hypothesised Mediator

In the multinomial logistic regression model examining variables associated with past month drinking patterns (Table 2), women 31 to 39 years of age had quadruple the odds of reporting frequent HED (RRR 4.40; 95% CI 1.75–10.89) than women ≥ 50 years of age. There was a trend towards women 18 to 30 years old being more likely to report frequent HED than women ≥ 50 years of age, but this was non-significant (RRR 3.21; 95% CI 0.95–10.85). Women who were unemployed were more likely to report frequent HED (OR 2.66; 95% CI 1.59–4.44) than those who were employed. Women with probable depression were less likely to report occasional HED (OR 0.11; 95% CI 0.05–0.23) or frequent HED (OR 0.13; 95% CI 0.05–0.30) than women without this comorbidity.

In the multivariable logistic regression model of factors associated with suboptimal adherence (Table 3), women who reported past-year illicit drug use (aOR 3.63; 95% CI 1.76–7.48), probable depression (aOR 1.85; 95% CI 1.14–3.01), occasional HED (aOR 3.07; 95% CI 1.78–5.30) or frequent HED (aOR 7.11; 95% CI 4.24–11.92) had significantly greater odds of suboptimal ART adherence than those without these exposures.

Variables Associated with Viral Non-suppression

In multivariate logistic regression analyses of viral non-suppression (Table 4), women between 18 to 30 and 31 to 39 years of age had more than double the odds of being non-suppressed relative to women ≥ 50 years of age (OR 2.51; 95% CI 1.32–4.78 and OR 2.23; 95% CI 1.13–4.41, respectively). Suboptimal ART adherence was associated with significantly greater odds of being virally non-suppressed (OR 1.75; 95% CI 1.20–2.57). Frequent HED but not occasional HED was associated with greater odds of being virally non-suppressed (OR 2.08; 95% CI 1.30–3.28) relative to no/light drinking. We found no evidence of significant interactions between age and drinking patterns or drinking patterns and adherence.

Results of Mediation Analyses

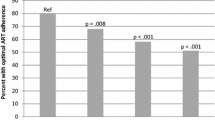

Findings show significant associations between occasional HED (β = 0.24, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001) and frequent HED (β = 0.45, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001) and suboptimal ART adherence. Depression was also associated with suboptimal adherence (β = 0.13, SE = 0.05, p = 0.014). In turn, suboptimal adherence was associated with HIV viral non-suppression (β = 0.57, SE = 0.18; p = 0.010). Frequent HED (β = 0.71, SE = 0.22, p = 0.005) but not occasional HED (β = -0.23, SE = 0.24, p = 0.335) or depression (β = -0.25, SE = 0.25, p = 0.329) was significantly associated with viral non-suppression.

None of the age categories were significantly associated with occasional HED (18–30 years old: β = 0.11, SE = 0.07, p = 0.125; 31 to 39 years old: β = 0.12, SE = 0.07, p = 0.823; 40–49 years old: β = 0.05, SE = 0.06, p = 0.436). Being 18–30 or 31–39 years of age was positively associated with frequent HED (β = 0.11, SE = 0.04, p = 0.011; β = 0.14, SE = 0.04, p = 0.001, respectively) and viral non-suppression (β = 0.93, SE = 0.30, p = 0.002; β = 0.80, SE = 0.33, p = 0.024, respectively). Being 40–49 years of age was not significantly associated with frequent HED (β = 0.05, SE = 0.03, p = 0.078) or viral non-suppression (β = 0.47, SE = 0.27, p = 0.101). Significant pathways are displayed in Fig. 1.

Results of the logistic decomposition analysis (Table 5) suggest that a significant part of the relationship between frequent HED and viral non-suppression is the result of a direct effect (OR 2.34, 95% CI 1.63–3.36). The smaller indirect effect suggests that suboptimal adherence only partially mediates the relationship between frequent HED and viral non-suppression (OR 1.24, 95% CI 1.05–1.46). Although the total effect of occasional HED on direct viral non-suppression was non-significant (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.62–1.62), there was a significant indirect effect (OR 1.11, 95% CI 1.03–1.21), suggesting that this pattern of drinking may indirectly affect viral non-suppression through its relationship with ART adherence.

Discussion

Alcohol consumption is a known risk for suboptimal ART adherence and viral non-suppression, however the pathways through which various drinking patterns affect viral suppression are poorly understood, particularly for WLWH [16, 17]. This study presents some of the first information on specific patterns of alcohol use associated with viral non-suppression and the extent to which adherence to ART mediates these relationships for WLWH. Findings indicate associations between frequent HED and viral non-suppression and clarify that the impact of heavy drinking on viral non-suppression is only partially due to its association with suboptimal ART adherence.

With only two-thirds of participants being virally suppressed and 10% having viral loads indicative of high infectiousness, our results underscore the importance of South Africa implementing a range of additional strategies to improve rates of viral suppression among WLWH to achieve the UNAIDS targets for eliminating HIV by 2030 [41]. In this study, frequent HED was one of the few factors associated with heightened risk of viral non-suppression, doubling the odds of viral non-suppression compared to no/light drinking. Notably, this pattern of drinking was concentrated among younger women who were also most at risk for being virally non-suppressed.

In keeping with Cook et al.’s study [23], our results show that suboptimal adherence only partially mediates the relationship between frequent HED and viral non-suppression. These findings suggest that mechanisms other than adherence account for a substantial part of the relationship between HED and viral load. Other plausible pathways through which heavy drinking may impact viral load include the effect of heavy alcohol use on the immune system (such as increasing inflammatory responses) that worsen disease progression [42, 43] and alcohol’s effect on the metabolism and effectiveness of antiretroviral medicines [44]. As evidence in support of these biological mechanisms is inconclusive, prospective cohort studies of WLWH on ART that examine both the behavioural and biological pathways through which various patterns of alcohol use may impact viral suppression are needed to clarify these relationships. Nonetheless, our results suggest that rates of viral suppression could be improved if evidence-based interventions focused on the detection and reduction of frequent HED are incorporated into HIV treatment services for women. At present, these behavioural health interventions are not part of the HIV treatment service offering within South Africa’s public health system [45].

In contrast, and like studies with men [20, 23], occasional HED was associated with greater risk of suboptimal ART adherence but did not seem to infer greater risk of viral non-suppression relative to alcohol consumption patterns characterised by abstinence or light drinking. Although CASE adherence index scores above the cut-off for optimal adherence correspond to ≥ 95% adherence, many of the newer ART medications retain their effectiveness with 80% adherence [46]. With most study participants being on first line medication, it is possible for women reporting occasional HED to score below the study cut-off optimal adherence yet still be virally suppressed. Even though occasional HED seems to have limited impacts on viral suppression, this pattern of drinking should still be addressed within the context of ART adherence and HIV care—especially for women who may be struggling with adherence. Brief interventions targeting reductions in the volume of alcohol consumed per drinking occasion may help women optimise their adherence to ART and could prevent progression to more frequent HED.

Study limitations need consideration when interpreting these findings. Our sample comprised adult women recruited as part of a trial, of whom 85% met criteria for probable depression. Findings may not be generalisable to the entire population of people on ART in South Africa. Further, we collected self-reported ART adherence and alcohol use data. Social desirability bias may have led to over-reporting of adherence and under-reporting of alcohol use leading to the misclassification of participants into adherence and alcohol use categories. However, studies comparing alcohol self-report and biomarker data for South African women and people on ART have noted low rates of alcohol under-reporting [47, 48]. Nonetheless, future studies should include biological indicators of alcohol use and ART adherence to validate self-report data. Related to this, although we used memory aids to improve participant’s recall of drinking occasions and standard drink estimation, these questions may be affected by recall bias, resulting in measurement error. Future studies could consider combining the collection of these self-report data with the use of technologies such as wearable transdermal alcohol monitors. These have shown promise in facilitating the continuous monitoring of alcohol consumption, although there are some concerns about the ability of these monitors to detect low and moderate levels of alcohol consumption [49]. Although this study did collect other information on alcohol consumption, as reflected through AUDIT-C scores [10], these are relatively blunt indicators of severity of alcohol consumption over a 12 month period providing little insight into various patterns of alcohol consumption that were of interest in this study. For these reasons, we chose not to use AUDIT-C scores in the current analyses. In addition, as analyses were limited to variables included in the MIND baseline assessment, we were unable to examine whether other factors (such as violence exposure and transactional sex) known to be associated with HED among women in this context [50, 51] affected ART adherence and viral suppression in this sample. Inclusion of these additional variables may reveal additional targets for contextually relevant, women-focused alcohol reduction interventions. Finally, data are cross-sectional and causal inferences between frequent HED and viral non-suppression cannot be established. Longitudinal research with a more representative sample of persons on ART is needed to confirm the direction of observed pathways and their clinical significance.

Conclusion

Study findings have implications for HIV service provision in South Africa and other countries similarly challenged by high rates of alcohol consumption. Alcohol reduction counselling is not routinely provided in the context of HIV care, where alcohol messaging has focused on cessation rather than reduction to within low risk limits [52, 53]. Findings highlight the need to integrate alcohol reduction interventions into HIV care to enable WLWH to reduce the quantity and frequency of their drinking. This is likely to benefit their ART adherence and help them attain viral suppression even if they continue drinking. Findings also point to the potential value of differentiated approaches to alcohol intervention delivery within the context of ART provision, tailored to specific patterns of alcohol consumption. For example, women who report occasional HED may benefit from brief interventions focused on reducing alcohol-related barriers to ART adherence and promoting low risk drinking. In contrast, women who report frequent HED may benefit from extended interventions focused on reducing alcohol use to less harmful patterns while also promoting better ART adherence when drinking.

Data Availability

Data reported in this paper are available on written request.

References

Marinda E, Simbayi L, Zuma K, Zungu N, Moyo S, Kondlo L, et al. Towards achieving the 90–90–90 HIV targets: results from the South African 2017 national HIV survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1375. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09457-z.

Cornell M, Johnson LF, Wood R, Tanser F, Fox MP, Prozesky H, et al. Twelve-year mortality in adults initiating antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21902. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.20.1.21902.

Johnson LF, May MT, Dorrington RE, Cornell M, Boulle A, Egger M, et al. Estimating the impact of antiretroviral treatment on adult mortality trends in South Africa: A mathematical modelling study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(12):e1002468. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002468.

Eisinger RW, Dieffenbach CW, Fauci AS. HIV viral load and transmissibility of HIV infection: undetectable equals untransmittable. JAMA. 2019;321(5):451–2.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Hakim JG, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505.

Trangenstein PJ, Morojele NK, Lombard C, Jernigan DH, Parry CDH. Heavy drinking and contextual risk factors among adults in South Africa: findings from the International Alcohol Control Study. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2018;13:43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-018-0182-1.

World Health Organization (WHO). Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018. Geneva: WHO. 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274603. Accessed 24 Feb 2021.

Kader R, Seedat S, Govender R, Koch JR, Parry CD. Hazardous and harmful use of alcohol and/or other drugs and health status among South African patients attending HIV clinics. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:525–34.

Parry CDH, Londani M, Shuper P, Myers B, Kekwaletswe CT, Nkosi S, et al. Patient characteristics and drinking behaviour of hazardous and harmful drinking among patients on ART who drink and attend HIV clinics in Tshwane, South Africa: implications for intervention. S Afr Med J. 2019;109:784–91.

Morojele N, Nkosi S, Kekwaletswe C, Shuper PA, Manda SO, Myers B, et al. Utility of brief versions of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) to identify excessive drinking among patients in HIV care in South Africa. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2017;78:88–96.

Veld DHI, Pengpid S, Colebunders R, Skaal L, Peltzer K. High-risk alcohol use and associated socio-demographic, health and psychosocial factors in patients with HIV infection in three primary health care clinics in South Africa. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(7):651–9.

Cichowitz C, Maraba N, Hamilton R, Charalambous S, Hoffman CJ. Depression and alcohol use disorder at antiretroviral therapy initiation led to disengagement from care in South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(12):e0189820. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189820.

Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, Altice FL. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112:178–93.

Grodensky CA, Golin CE, Ochtera RD, Turner BJ. Systematic review: effect of alcohol intake on adherence to outpatient medication regimens for chronic diseases. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:899–910.

Velloza J, Kemp CG, Aunon FM, Ramaiya MK, Creegan E, Simoni JM. Alcohol use and antiretroviral therapy non-adherence among adults living with HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(6):1727–42.

Williams EC, Hahn JA, Saitz R, Bryant K, Lira MC, Samet JH. Alcohol use and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: current knowledge, implications, and future directions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(10):2056–72.

Barai N, Monroe A, Lesko C, Hutton H, Lang C, Alvanzo A. The association between changes in alcohol use and changes in antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression among women living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(7):1836–45.

Deiss RG, Mesner O, Agan BK, Ganesan A, Okulicz JF, Bavaro M, et al. Characterizing the association between alcohol and HIV virologic failure in a military cohort on antiretroviral therapy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(3):529–35.

Sacamano PL, Farley JE. Behavioral and other characteristics associated with HIV viral load in an outpatient clinic. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(11):e0166016. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166016.

Kahler CW, Liu T, Cioe PA, Bryant V, Pinkston MM, Kojic EM, et al. Direct and indirect effects of heavy alcohol use on clinical outcomes in a longitudinal study of HIV patients on ART. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(7):1825–35.

Conen A, Wang Q, Glass TR, Fux CA, Thurnheer MC, Orash C, et al. Association of alcohol consumption and HIV surrogate markers in participants of the swiss HIV cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(5):472–8.

Sullivan KA, Messer LC, Quinlivan EB. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV/AIDS syndemic effects on viral suppression among HIV positive women of color. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(Suppl 1):S42–8.

Cook RL, Zhou Z, Kelso-Chichetto NE, Janelle J, Morano JP, Somboonwit C, et al. Alcohol consumption patterns and HIV viral suppression among persons receiving HIV care in Florida: an observational study. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2017;12(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-017-0090-0.

Lipira L, Rao D, Nevin PE, Kemp CG, Cohen SE, Turan JM, et al. Patterns of alcohol use and associated characteristics and HIV-related outcomes among a sample of African-American women living with HIV. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;206:107753.

Erol A, Karpvak VM. Sex and gender-related differences in alcohol use and its consequences. Contemporary knowledge and future research considerations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;156:1–13.

Hahn JA, Cheng DM, Emenyonu NI, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Fatch R, Shade SB, et al. Alcohol use and HIV disease progression in an antiretroviral naive cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(5):492–501.

Abdullah F, Naledi T, Nettleship E, Davids EL, Lieve L, Shangase S, et al. First social impact bond for the SAMRC: a novel financing strategy to address the health and social challenges facing adolescent girls and young women in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2019;109(11b):57–62.

Myers B, Lund C, Lombard C, Joska J, Levitt N, Butler C, et al. Comparing dedicated and designated models of integrating mental health into chronic disease care: study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Trials. 2018;19:185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2568-9.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401.

Jani BD, McQueenie R, Nicholl BI, et al. Association between patterns of alcohol consumption (beverage type, frequency and consumption with food) and risk of adverse health outcomes: a prospective cohort study. BMC Med. 2021;19:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01878-2.

Onya H, Tessera A, Myers B, Flisher A. Community influences on adolescents’ use of home-brewed alcohol in rural South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:642. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-642.

Rehm J. How should prevalence of alcohol use disorders be assessed globally? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2016;25:79–85.

Mekuria LA, Prins JM, Yalew AW, Sprangers MA, Nieuwkerk NT. Which adherence measure—self-report, clinician recorded or pharmacy refill—is best able to predict detectable viral load in a public ART programme without routine plasma viral load monitoring? Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21(7):856–69.

Mannheimer SB, Mukherjee R, Hirschhorn LR, Dougherty J, Celano SA, Ciccarone D, et al. The CASE adherence index: a novel method for measuring adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care. 2006;18(7):853–61.

Heestermans T, Browne JL, Aitken SC, Vervoet SC, Klipstein-Grobush K. Determinants of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive adults in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2016;1(4):e000125. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000125.

Parry CD, Morojele NK, Myers BJ, Kekwaletswe CT, Manda SOM, Sorsdahl K, Ramjee G, et al. Efficacy of an alcohol-focused intervention for improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and HIV treatment outcomes - a randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:500. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-500.

Sherbourne C, Stewart A. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705–14.

Albert JM, Geng C, Nelson S. Causal mediation analysis with a latent mediator. Biom J Biometrische Zeitschrift. 2016;58(3):535–48.

Gunzler D, Chen T, Wu P, Zhang H. Introduction to mediation analysis with structural gequation modeling. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2013;25(6):390–4.

Buis ML. Direct and indirect effects in a logit model. Stat J. 2010;10:11–29.

UNAIDS. An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2014. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/90-90-90_en_0.pdf

Monnig MA. Immune activation and neuroinflammation in alcohol use and HIV infection: evidence for shared mechanisms. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43:7–23.

So-Armah KA, Cheng DM, Freiberg MS, Gnatienko N, Patts G, Ma Y, et al. Association between alcohol use and inflammatory biomarkers over time among younger adults with HIV-The Russia ARCH Observational Study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(8):e0219710. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219710.

Kumar S, Jin M, Ande A, Sinha N, Silverstein PS, Kimar A. Alcohol consumption effect on antiretroviral therapy and HIV-1 pathogenesis: role of cytochrome P450 isozymes. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2012;8(11):1363–75.

Sorsdahl K, Naledi T, Lund C, Levitt NS, Joska JA, Stein DJ, et al. Integration of mental health counselling into chronic disease services at the primary healthcare level: formative research on dedicated vs designated strategies in the Western Cape, South Africa. J Health Services Res Policy. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819620954232.

Viswanathan S, Justice AC, Alexander GC, Brown TT, Gandhi NR, McNicholl IR, et al. Adherence and HIV RNA suppression in the current era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(4):493–8.

May PA, Hasken JM, De Vries MM, Marais AS, Stiegal J, Marsden D, et al. A utilitarian comparison of two alcohol use biomarkers with self-reported drinking history collected in antenatal clinics. Reprod Toxicol. 2018;77:25–32.

Hahn JA, Murnane PM, Vittinghoff E., Muyindike WR, Emenyonu NI, Fatch R, et al. Factors associated with phosphatidylethanol (PEth) sensitivity for detecting unhealthy alcohol use: An individual patient data meta‐analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021 Accepted Author Manuscript. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14611

van Egmond K, Wright CJC, Livingston M, Kuntsche E. Wearable transdermal alcohol monitors: a systematic review of detection validity, and relationship between transdermal and breath alcohol concentration and influencing factors. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2020;44(10):1918–32.

Petersen Williams P, Brooke-Sumner C, Joska J, Kruger J, Vanleeuw L, Dada S, Sorsdahl K, Myers B. Young South African women on antiretroviral therapy perceptions of a psychological counselling program to reduce heavy drinking and depression. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2249. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072249.

Magni S, Christofides N, Johnson S, Weiner R. Alcohol use and transactional sex among women in south africa: results from a Nationally Representative Survey. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0145326. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145326.

Howard BN, Van Dorn R, Myers BJ, Zule WA, Browne FA, Carney T, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing an evidence-based woman-focused intervention in South African Health Services. BMC Health Services Res. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2669-2.

Satinsky EN, Myers B, Andersen LS, Kagee SA, Joska JA, Magidson JF. “Now we are told that we can mix”: messages and beliefs around simultaneous use of alcohol and ART. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:2680–90.

Funding

This study is funded jointly by the British Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, Department for International Development, the Economic and Social Research Council, the Global Challenges Research Fund (MR/M014290/1) as well as funding from the South African Medical Research Council’s Office of AIDS and TB Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BM and KRS conceptualized the study. PPW managed trial implementation and data collection. BM and CJL conducted the analyses. BM developed the first draft of the manuscript that all authors commented on. All authors edited and agreed on the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical Approval

The South African Medical Research Council (EC 004–2/2015), the University of Cape Town (089/2015), Oxford University (OxTREC 2–17) and the Western Cape Department of Health (WC2016_RP6_9) provided ethical approval for this study.

Informed Consent

Individual, written informed consent was obtained from participants for all study activities.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Myers, B., Lombard, C., Joska, J.A. et al. Associations Between Patterns of Alcohol Use and Viral Load Suppression Amongst Women Living with HIV in South Africa. AIDS Behav 25, 3758–3769 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03263-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03263-3