Abstract

HIV incidence among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Greece remains unchanged despite effective response to a recent outbreak among people who inject drugs (PWID). Network factors are increasingly understood to drive transmission in epidemics. The primary objective of the study was to characterize MSM in Greece, their sexual behaviors, and sexual network mixing patterns. We investigated the relationship between serostatus, sexual behaviors, and self-reported sex networks in a sample of MSM in Athens, Greece, generated using respondent driven sampling. We estimated mixing coefficients (r) based on survey-generated egonets. Additionally, multiple logistic regression was used to estimate adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and to assess relationships between serostatus, sexual behaviors, and sociodemographic indicators. A sample of 1,520 MSM participants included study respondents (n = 308) and their network members (n = 1,212). Mixing based on serostatus (r = 0.12, σr = 0.09–0.15) and condomless sex (r = 0.11, σr = 0.07–0.14) was random. However, mixing based on sex-drug use was highly assortative (r = 0.37, σr = 0.32–0.42). This study represents the first analysis of Greek MSM sexual networks. Our findings highlight protective behavior in two distinct network typologies. The first typology mixed assortatively based on serostatus and sex-drug use and was less likely to engage in condomless sex. The second typology mixed randomly based on condomless sex but was less likely to engage in sex-drug use. These findings support the potential benefit of HIV prevention program scale-up for this population including but not limited to PrEP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Of the 628 new HIV infections in Greece in 2017, 292 (46.5%) were among men who have sex with men (MSM), and 8,074 (48.4%) of the 16,669 new HIV diagnoses from 2008–2017 were made in MSM [1]. MSM incidence has remained relatively unchanged in the context of an effective response to an outbreak among people who inject drugs (PWID) [2] and has returned to its pre-outbreak position as the largest percentage of new HIV infections in Greece [1]. Furthermore, some evidence that the PWID epidemic could move into the men who have sex with men (MSM) population has emerged [3].

After the 2010 European MSM Internet Survey (EMIS) provided some behavioral data on MSM in Greece, including sexual practices, HIV testing, antiretroviral therapy, and drug use, information on HIV in MSM in Greece has been improving [4]. Representative data on HIV testing and condom use among MSM is still limited [5]. Other gaps include data on MSM subgroups such as migrants, those who use alcohol and recreational drugs, and those with poor mental health, all of whom may be at higher risk of HIV infection [6].

The higher incidence of HIV among Greek MSM compared to other groups may not be explained by individual-level behaviors alone. It may be attributed in part to pockets of infection [7], sexual network factors, and bridging behaviors between MSM as evident in other contexts [8,9,10]. Such networks may contribute to the higher incidence rates and provide opportunities for future preventative interventions. For example, higher rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have been found to be related to sexual network mixing patterns such as assortativity and concurrent sex partners [11,12,13,14]. Some research has explained disparities in HIV rates by examining sexual network mixing patterns within subgroups [15, 16]. This research demonstrated that higher levels of disassortative mixing (high prevalence groups mixing with low prevalence groups) contributed to disproportionately higher STI incidence.

Since sex practices and network analysis of most vulnerable populations in Greece has focused on PWID [17,18,19,20,21] and not specifically on MSM, despite the majority of cumulative HIV cases being among MSM [19, 22], results from other geographic areas on MSM social and sexual behaviors and networks may be instructive. A study [23] in South Florida, New York City, and Baltimore from 2011 demonstrated that the amount of time MSM lived in an area was associated with sexual behaviors and HIV infection. Known behaviors associated with HIV infection among MSM include sex-drug use [24] and condomless sex (CS) [10]. While these behaviors have been included in previous investigation in Greece [4, 25], they have never been examined among MSM in Greece. Furthermore, network patterns that potentially confer risk, such as disassortative sexual mixing, especially between HIV-positive and HIV-negative MSM, also have not been explored within this population. To that end, an analysis of MSM sexual networks in Greece was conducted characterize associations between network characteristics and HIV serostatus. We hypothesize that mixing between study respondents and sex network members will demonstrate assortative (r ≥ 0.35) [10, 11] mixing for select sex behaviors and serostatus.

Methods

Between November 2016 and April 2018, a sample of Greek MSM (n = 308) was recruited in Athens using respondent-driven sampling (RDS) [26]. From that sample, as visualized in Fig. 1, respondents reported sex network members (n = 1212) to generate a total sample of respondents and network members (n = 1520). Computer-assisted interviews were carried out with the respondents by a certified nurse at the partner organization, Checkpoint Athens, a lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender testing, prevention, and health information center. Voluntary HIV counseling and testing were conducted in accordance with national regulations and per the standard operating procedures of Checkpoint Athens. Procedures and protocols were approved by institutional review boards at the University of Chicago, the Hellenic Scientific Society for the Study of AIDS and STDs, and the Scientific Council of Laiko General Hospital of Athens. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents.

Study Participants

Study participants included both respondents who were interviewed and the sex network members about whom they reported. Respondents were eligible if they identified as male, were a resident of the Athens Metropolitan Area, were 18 years of age or older, reported sexual intercourse with a man within the past 12 months, could communicate in either Greek or English, planned to remain in Athens for 12 months, and were willing and able to provide informed consent at the time of the interview. Eligibility was assessed twice, during initial interviews and again during analysis.

Recruitment

RDS has consistently been used as an effective approach for recruiting and developing population estimates of vulnerable populations such as PWID, sex workers, and MSM [27,28,29,30]. Its advantages and shortcomings have been assessed theoretically and empirically [27, 31,32,33], and this method was selected due to its utility in risk factor identification, network data collection, and implementation of interventions. Previous work emphasized the importance of careful community-informed selection of seeds and iterative rounds of recruitment to thoroughly sample the investigation population [31, 32, 34]. Between November 2016 and April 2018, we followed this strategy to recruit a sample with seeds (n = 61). Seeds who were identified by staff from Laiko General Hospital of Athens and Checkpoint Athens. The recruiter-recruit relationship was not tracked. Seeds were required to meet the above eligibility criteria and demonstrate social connections within the Greek MSM community. Seeds and respondents whom they recruited were remunerated 10 euros (increased to 20 euros after six months to encourage recruitment), distributed five coupons for recruits who met study criteria and had multiple sex partners, and remunerated 5 euros (10 euros as above) for each coupon returned by a recruit who participated in the study. Incentives were increased in May 2017 when recruitment analysis showed an insufficient rate of data collection for the proposed study period to meet levels of precision obtainable from smaller sample sizes in non-RDS studies [31]. We conducted entity resolution to limit the duplication of respondents and sex network partners.

Survey Instruments

Survey instruments on demographics, behaviors shown to be associated with HIV serostatus, and sexual behavior were adapted from a recent MSM cohort study [35] for face-to-face interviews. Information about age, education, employment status, housing status, marital status, insurance coverage, nationality, sexual practices, PrEP awareness, and drug-use behaviors was collected from respondents in a manner consistent with that used to analyze the HIV outbreak among PWID in Greece in 2012 [20]. Information on respondent condomless sex was solicited through the survey question “When you had anal sex, did you use any condoms?” Respondent sex-drug use was solicited with “When you had sex, did you use drugs or alcohol to make your sexual experience more intense?” [24, 36].

Survey instruments were forward and backward translated from English into Greek and verified by Athens Checkpoint staff.

Sex Network Assessment

To collect egocentric network data [37], the SOPHOCLES survey instrument adopted established methods that have been used in several other large surveys, including the General Social Survey [38], the National Health and Social Life Survey [39], the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project [40], and uConnect [41].

Respondents were asked to report behavioral data on individuals with whom they had sex in the 6 months prior to the interview. First, the interviewer elicited a series of sex network members from each respondent. From that list, additional information was obtained on five sex network members. Five was selected given previous work suggesting this is optimal for time and effort in field egocentric network surveys [42]. A series of questions about each sex network member’s demographic attributes and a description of the nature of the relationship followed. Further sex behavior and drug use information on sex network members was also elicited, and referrals for HIV prevention services including testing, counseling, substance use treatment, and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) were provided.

We focused on two core sex behaviors as our primary outcomes, condomless sex and sex-drug use, given their importance in sexual network mixing and transmission [10] in environments where PrEP is not readily available such as in Athens. For sex network members, condomless sex was measured in response to the question “How often do you believe that this sex partner has anal sex without the use of a condom?" Sex network member sex-drug use was measured in response to the question “How often do you believe that this sex partner uses drugs or alcohol to make sex easier, last longer, or feel better?" These behavioral measures were assessed in frequency terms over the past year and coded as existent if present more than once in the past year.

HIV Counseling and Testing

Interviews, testing, and counseling were all carried out at the Athens Checkpoint office with linkage to care at Laiko General Hospital of Athens as appropriate. All respondents were initially tested for HIV with a fingerstick, using the INSTI HIV-1/HIV-2 Rapid Antibody Test. In the case of positive tests, follow-up blood testing with Genscreen™ ULTRA HIV Ag-Ab, ARCHITECT HIV Ag/Ab Combo, and Bio-rad Western Blot testing was used to confirm serostatus. Checkpoint staff conducted pre- and post-test counseling with all respondents.

Respondent-Level Analyses

We conducted three multiple logistic regressions to determine the relationship between serostatus, the sex behaviors just described, and sociodemographic characteristics as in this study [43]. The first regression assessed the effect of variables such as sex behaviors and sociodemographic characteristics on HIV serostatus. In the second regression, the outcome was sex-drug use and in the third condomless sex. In each model, we adjusted for age, education status, nationality, and relationship status. Seeds were included in analysis. RDS weights were applied to all models using the Giles Sequential Sampling approach [44]. Models were also run without RDS weights as in similar work [45].

Mixing Analysis

Assortativity coefficients (r) [46] were calculated to describe the sexual mixing patterns (i.e. homophilic or “like-with-like”) in our sample. For HIV status, for example, by tabulating the proportions of the two types (HIV-positive with HIV-positive and HIV-negative with HIV-negative) of seroconcordant dyads and the two types of serodiscordant dyads (HIV-positive with HIV-negative and HIV-negative with HIV-positive), a two-by-two mixing matrix of the four types of ties above was constructed. Using a similar technique, assortativity coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed for sex-drug use and condomless sex. An assortativity coefficient of r = 1 indicates complete assortative mixing, where all ties would be seroconcordant. Coefficient of r = − 1 would indicate total disassortative mixing, where all ties would be serodiscordant. When r = 0, this indicates random mixing [47]. Based on previous work, coefficients of 0.35 or larger are generally characterized as assortative, 0.26 to 0.34 as moderately assortative, and 0.15 to 0.25 as minimally assortative [10, 11].

Results

The sample included a total network (n = 1,520) generated from 61 seeds and included respondents (n = 308) and sex network members (n = 1212) as demonstrated in Fig. 1. The RDS seeds generated the full respondent sample with non-zero networks averaging 17.1 seed respondents and a maximum number of 11 waves. Seed productivity demonstrated a wide range (0–107) with 35 non-productive seeds (57.3%).

Respondent and Sex Network Member Characteristics

Attributes of respondents and sex network members are depicted in Table 1. The prevalence of HIV in respondents (8.4%) and sex network members as known by respondents (10.4%) were similar. HIV prevalence of sex network members reported by seropositive respondents (20.0%) was double that (9.2%) reported by seronegative respondents about their sex network members. HIV PrEP awareness among respondents was 73.7%. A majority of respondents (87.0%) and sex network members (83.2%) were Greek nationals, and a majority of respondents (60.0%) and sex network members (70.5%) were employed.

The distribution of sexual behavior characteristics for respondents and respondents' perceptions of their sex network members' behavior is depicted in Table 2. Sex-drug use for respondents (45.6%) and respondents' perceptions of the sex-drug use of their sex network members (54.4%) were more similar than condomless sex for respondents (17.6%) and respondents' perceptions of the condomless sex of their sex network members (62.7%). The distribution of sexual behavior characteristics stratified by respondent HIV status is also depicted in Table 2. Again, sex-drug use showed less difference. Similar sex-drug use reported by seropositive (45.4%) and seronegative (45.6%) respondents was about 10% lower than seropositive (56.7%) and seronegative (54.1%) respondents' perceptions of the sex-drug use of their sex network members. However, the condomless sex reported by seropositive respondents (30.0%) was nearly twice that of seronegative respondents (16.2%). Furthermore, respondents reported significantly higher condomless sex by their sex network members regardless of whether the respondent was seropositive (58.7%) or seronegative (61.3%).

Respondent-Level Regression Results

In regression analysis with adjusted odds ratios (AOR) depicted in Table 3, two sexual behaviors demonstrated statistical significance. Respondents who reported sex-drug use were significantly less likely to report condomless sex (AOR 0.47; 95% CI 0.27, 0.80) and respondents who reported condomless sex were significantly less likely to report sex-drug use (AOR 0.49; 95% CI 0.27, 0.80).

Other statistically significant associations included that older respondents were more likely to be HIV-positive (AOR per annum 1.10; 95% CI 1.05, 1.15). Non-Greek respondents were less likely to report condomless sex (AOR 0.30; 95% CI (0.14, 0.64).

Sex Tie Characteristics

Characteristics of ties between respondents and sex network members are shown in Table 4. A minority of the ties measured (17.9%) occurred in the context of a relationship such as husband or boyfriend. More than two-thirds (66.9%) of ties were established via the internet or telephone. Additionally, one in ten (10.9%) of respondents reported that at least one of their last five sex network members in the past 6 months had sexual contact with another identified member, creating concurrent ties and sex network triads.

Network Mixing

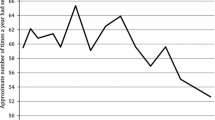

Our mixing analysis of sexual behaviors (sex-drug use and condomless sex) is depicted in Fig. 2 and further stratified by HIV status.

Mixing within sexual networks by sexual behavior and HIV status (n = 1550). Assortativity coefficients (ACs)a for two behaviors—sex-drug use and condomless sex—and HIV status of MSM respondents and sex network members are depicted here. Nodes and error bars within each behavior category indicate the AC for all dyads in the sample. ACs are also stratified by HIV status of respondents. An AC of 1 would indicate perfectly assortative mixing, e.g., respondents who practice a behavior only have sex with those who also practice that behavior, while respondents who do not practice the behavior only have sex with those who also do not practice the behavior. aThe Assortativity Coefficient (AC) is calculated from the mixing matrix—the proportion of total ties in a cross-tabulation of ties between people who do and do not engage in a sexual behavior

Mixing of study participants based on sex-drug use was assortative (like with like) (r = 0.37, σr = 0.32–0.42). When stratified by tested HIV status of respondents, mixing based on sex-drug use in the HIV-positive stratum was moderately assortative (r = 0.26, σr = 0.12–0.41). Similarly, mixing based on sex-drug use behavior in the HIV-negative stratum was also moderately assortative (r = 0.25, σr = 0.20–0.30).

Mixing with regards to condomless sex and HIV status did not display assortative mixing. Respondents and sex network members mixed randomly based on condomless sex (r = 0.11, σr = 0.07–0.14) and positive HIV status (r = 0.12, σr = 0.09–0.15). In our study then, except for sex-drug use, the sexual behavior of respondents had no tendency to be similar to that of their self-reported sex network members even when serostatus was considered. Weighted and unweighted results did not differ.

Discussion

While attention has been devoted to sex behaviors [4] and drug-use networks [19, 20] in Greece, most HIV network epidemiology in Greece has focused on PWID [18, 20, 21, 48, 49]. Our study represents the first network analysis that investigated the role of networks with regards to sexual behaviors and HIV serostatus in MSM in Greece.

We have two major findings related to prevention of onward transmission of HIV in this context. The first is a network typology of MSM demonstrating assortative mixing based on sex-drug use who seem to have adopted two protective behaviors (serosorting and sex with condoms) and who have an unclear awareness of PrEP. The second is a network typology of MSM engaging in condomless sex who seem to have adopted one protective behavior (avoiding partners who engage in sex-drug use) and also have an unclear awareness of PrEP. Both represent intervention opportunities.

Participants demonstrated assortative (r ≥ 0.35) [25] mixing for only one sexual behavior: sex-drug use. This suggests that Greek MSM who engage in sex-drug use behavior perceive their sex network members as having similar sex-drug use behavior.. Furthermore, seropositive Greek MSM who also engage in sex-drug use tend to do so with other seropositive MSM. Seronegative Greek MSM similarly self-segregate when engaging in sex-drug use. The observed assortative sexual mixing pattern for sex-drug use is consistent with previous findings and is an example of serosorting—a behavior that limits sexual activity to partners of the same serostatus and is thought to be protective in some contexts [15, 16, 50, 51]. The finding in regression analysis that those who use drugs to enhance sex have adopted a second protective sexual behavior (avoiding condomless sex) suggests this group could be an effective target [52] of safe drug and condom use interventions. The same phenomenon could occur with PrEP use considering this group's limited PrEP awareness (AOR 1.38; 95% CI 0.70, 2.70). Thus, the first network typology still seems amenable to promotion of condom and PrEP use in the context of sex-drug use.

Contrary to our hypothesis and what has been observed in other MSM populations [10], no sex network sorting on other behaviors was apparent. Network member preference for partners with similar behavior profiles for condomless sex and HIV status was found to be nearly random (r ≤ 0.15) [9] regardless of stratification by serostatus. These heterogenous results are surprising because sex ties have been shown previously to be based on shared sexual behaviors [10, 11]. While evidence of preference with regards to only one sex behavior is inconsistent with more comprehensive strategic mixing found previously, it does not suggest random mixing as the driving factor behind the unchanged HIV incidence in Greek MSM. Other research has demonstrated levels of serosorting to be unrelated to HIV incidence disparities between sub-populations [53, 54]. Additionally, the random mixing based on serostatus and condomless sex could be viewed as an interventional target. Finally, since our analysis did not investigate the incidence rates of other STIs, we cannot examine how mixing contributed to their incidence.

Although the second network typology demonstrated neither serosorting nor sorting based on condom use in mixing analysis, those respondents did show a protective preference for partners with no sex-drug use in regression analysis. Having adopted this protective behavior, the second typology also represents an interventional target. Such interventions should take note of the protective preference and its implication on behavior propagation.

Social learning and differential association theories [55, 56] assert that sex behaviors and the conceptualizations for them propagate through social and sexual networks. Network members demonstrate and normalize specific sex behavior, reshaping MSM perceptions of these behaviors [57,58,59]. Research has shown in various contexts that individual perception of network members can induce individual sexual and substance use behaviors [10, 60,61,62]. In light of these theories, random mixing on condomless sex has implications on the propagation of this behavior and through Greek MSM sexual networks, especially as evidence of decreasing condom use with PrEP rollout emerges [63] in some locations. For example, in a state of random mixing such as observed here, sexual partners of different condom use preferences are more likely to encounter each other. Conversely, network members mixing assortatively would more rarely encounter partners with different preferences. The higher frequency of encounters between partners with different condom use preferences presents more opportunities for perception change and behavior propagation. Such interventions should take note of the protective preference and its implication on behavior propagation.

While disassortativity for condomless sex has been observed in other MSM networks globally, cautious comparison of these results is still necessary due to the vastly different populations and settings. Regardless, for the second network typology, stakeholders could look to primary prevention efforts such as PrEP provision, condom use promotion, and increasing the awareness of the HIV status of sexual partners as well as secondary prevention efforts such as programs that engage with HIV-positive MSM to prevent onward transmission. Evidence-based interventions more targeted to specific network characteristics [64, 65] are still developing and require further investigation.

As an update of the demographics of MSM in Greece, the prevalence of HIV in the study sample as reported above was consistent with that reported among Greek MSM by the European Center for Disease Control (ECDC) in 2014 (6). However, sex-drug use was significantly higher for respondents (45.6%) and sex network members (54.4%) in our sample than regional percentages (6.6%) reported in EMIS in 2010 [4]. Condomless sex was slightly lower.

The continuing effort to illuminate the sex networks and transmission of HIV between Greek MSM must go beyond the mixing of high-risk and low-risk individuals. Social ties have been shown to be critical to disease transmission [10, 66]. Due to collectivist cultural and religious influences [67], they may be even more significant in Greece. Therefore, longitudinal social and sex network analysis should be pursued to unravel the nexus of sexual behavior profiles, assortativity, social influence, behavior norms and normalization, and network behavior propagation to construct better individual and network interventions.

Limitations

Several potential limitations affect this study. The aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis on Greece is still playing out. Rigorous research has shown its effects on the spread of HIV among PWID [17,18,19,20]. The possibility of residual influences on the MSM population cannot be ignored, especially as phylogenetic evidence of spillover of the PWID epidemic into the MSM population continues to emerge [68].

Despite the great need for sampling and inference methods to investigate hard-to-reach groups, uncertainty regarding how well RDS generates representative samples and unbiased analysis still faces investigators [31]. Even the uncertain ability to detect bias in RDS impels the reader to consider that our CIs could be too narrow and that inferences drawn from our sample may not be applicable to a wider population. Additionally, data analysis and anecdotal investigation could not elucidate why 35 seeds were non-productive.

As is typical of egocentric network analysis, all data were self-reported by respondents, and thus are susceptible to projection bias [69] and pluralistic ignorance [70]. This limitation could lead to overreporting of shared characteristics and thus falsely elevated assortativity. Respondents have also been shown to under-report their own stigmatized behavior and over-report their partners' behaviors [71,72,73], which would falsely depress assortativity. Another limitation is the potential overlap between respondents and sex network partners. Finally, the low number of HIV-positive participants in the sample lead to weak variability and increased the standard error for measurements related to HIV-positive participants, possibly reducing the power to identify associations.

Conclusion

This study represents the first network analysis of the sexual mixing patterns of Greek MSM. Our two major findings relate to protective sexual behavior among MSM in Greece. The first is a network typology of serosorting MSM, engaging in assortative mixing based on sex-drug use, who are more likely to engage in sex with condoms. The second is a network typology of MSM, who despite being less likely to engage in sex-drug use, mix randomly based on condomless sex and are thus susceptible to the propagation of that sexual behavior seen elsewhere. Both represent interventional opportunities to reduce transmission, slow the spread of HIV, and facilitate prevention. The effectiveness of PrEP in these contexts should be explored.

References

Patrinos S, Gkotzani O, Issaris C, Oikonomou F, Paraskeva D, Pylli M, et al. HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Greece Data reported through 31.12.2017 [Internet]. Athens, Greece: Hellenic Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017 Dec p. 40. Report No.: no 32. http://www.keelpno.gr/Portals/0/%CE%91%CF%81%CF%87%CE%B5%CE%AF%CE%B1/HIV/2018/%CE%95%CE%A0%CE%99%CE%94%CE%97%CE%9C%CE%99%CE%9F%CE%9B%CE%9F%CE%93%CE%99%CE%9A%CE%9F_%CE%94%CE%95%CE%9B%CE%A4%CE%99%CE%9F_HIV_2017.pdf

Sypsa V, Psichogiou M, Paraskevis D, Nikolopoulos G, Tsiara C, Paraskeva D, et al. Rapid decline in HIV incidence among persons who inject drugs during a fast-track combination prevention program after an HIV outbreak in Athens. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1496–505.

Kostaki E, Magiorkinis G, Psichogiou M, Flampouris A, Iliopoulos P, Papachristou E, et al. Detailed molecular surveillance of the HIV-1 outbreak among people who inject drugs (PWID) in Athens during a period of four years. Curr HIV Res. 2017;15:396–404.

EMIS-2010-Community-Report-Two-2011.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2018. http://gayhealthnetwork.ie/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/EMIS-2010-Community-Report-Two-2011.pdf

Dublin-declaration-hiv-data-evidence-brief.pdf. https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/dublin-declaration-hiv-data-evidence-brief.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2018

Dublin-declaration-msm-2014.pdf. https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/dublin-declaration-msm-2014.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2018

Friedman SR, Jose B, Deren S, Des Jarlais DC, Neaigus A. Risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among out-of-treatment drug injectors in high and low seroprevalence cities. The National AIDS Research Consortium. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:864–74.

Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1007–19.

Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS Lond Engl. 2007;21:2083–91.

Schneider JA, Cornwell B, Ostrow D, Michaels S, Schumm P, Laumann EO, et al. Network mixing and network influences most linked to HIV infection and risk behavior in the HIV epidemic among black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e28-36.

Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Adimora AA. Sexual mixing patterns and heterosexual HIV transmission among African Americans in the southeastern United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2009(52):114–20.

Laumann EO, Youm Y. Racial/ethnic group differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: a network explanation. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:250–61.

Aral SO. Sexual network patterns as determinants of STD rates: paradigm shift in the behavioral epidemiology of STDs made visible. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:262–4.

Doherty IA, Padian NS, Marlow C, Aral SO. Determinants and consequences of sexual networks as they affect the spread of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Suppl 1):S42-54.

Laumann EO, Ellingson S, Mahay J, Paik A, Youm Y. The sexual organization of the city. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2004.

Rothenberg R, Dan My Hoang T, Muth SQ, Crosby R. The Atlanta urban adolescent network study: a network view of STD prevalence. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:525–31.

Nikolopoulos GK, Fotiou A, Kanavou E, Richardson C, Detsis M, Pharris A, et al. National income inequality and declining GDP growth rates are associated with increases in HIV diagnoses among people who inject drugs in Europe: a panel data analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0122367.

Nikolopoulos GK, Sypsa V, Bonovas S, Paraskevis D, Malliori-Minerva M, Hatzakis A, et al. Big events in Greece and HIV infection among people who inject drugs. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50:825–38.

Tsang MA, Schneider JA, Sypsa V, Schumm P, Nikolopoulos GK, Paraskevis D, et al. Network characteristics of people who inject drugs within a new HIV epidemic following austerity in Athens, Greece. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69:499–508.

Sypsa V, Paraskevis D, Malliori M, Nikolopoulos GK, Panopoulos A, Kantzanou M, et al. Homelessness and other risk factors for HIV infection in the current outbreak among injection drug users in Athens. Greece Am J Public Health. 2015;105:196–204.

Williams LD, Kostaki E-G, Pavlitina E, Paraskevis D, Hatzakis A, Schneider J, et al. Pockets of HIV non-infection within highly-infected risk networks in Athens. Greece Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1825.

20121130-Risk-Assessment-HIV-in-Greece.pdf. https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/20121130-Risk-Assessment-HIV-in-Greece.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2018

Egan JE, Frye V, Kurtz SP, Latkin C, Chen M, Tobin K, et al. Migration, neighborhoods, and networks: approaches to understanding how urban environmental conditions affect syndemic adverse health outcomes among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(Suppl 1):S35-50.

Unequal opportunity: health disparities affecting gay and bisexual men in the United States. Oxford University Press, Oxford; 2007 http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195301533.001.0001/acprof-9780195301533. Accessed 25 May 2018

Hatzakis A, Sypsa V, Paraskevis D, Nikolopoulos G, Tsiara C, Micha K, et al. Design and baseline findings of a large-scale rapid response to an HIV outbreak in people who inject drugs in Athens, Greece: the ARISTOTLE programme. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2015;110:1453–67.

Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44:174–99.

Iguchi MY, Ober AJ, Berry SH, Fain T, Heckathorn DD, Gorbach PM, et al. Simultaneous recruitment of drug users and men who have sex with men in the United States and Russia using respondent-driven sampling: sampling methods and implications. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2009;86:5–31.

Johnston LG, Khanam R, Reza M, Khan SI, Banu S, Alam MS, et al. The effectiveness of respondent driven sampling for recruiting males who have sex with males in Dhaka. Bangladesh AIDS Behav. 2008;12:294–304.

Ramirez-Valles J, Heckathorn DD, Vázquez R, Diaz RM, Campbell RT. From networks to populations: the development and application of respondent-driven sampling among IDUs and Latino gay men. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:387–402.

Mimiaga MJ, Goldhammer H, Belanoff C, Tetu AM, Mayer KH. Men who have sex with men: perceptions about sexual risk, HIV and sexually transmitted disease testing, and provider communication. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:113–9.

White RG, Lansky A, Goel S, Wilson D, Hladik W, Hakim A, et al. Respondent driven sampling–where we are and where should we be going? Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88:397–9.

Gile KJ, Handcock MS. Respondent-driven sampling: an assessment of current methodology. Sociol Methodol. 2010;40:285–327.

Goel S, Salganik MJ. Respondent-driven sampling as Markov chain Monte Carlo. Stat Med. 2009;28:2202–29.

Schneider J, Cornwell B, Jonas A, Lancki N, Behler R, Skaathun B, et al. Network dynamics of HIV risk and prevention in a population-based cohort of young Black men who have sex with men. Netw Sci. 2017;5:381–409.

Morgan E, Khanna AS, Skaathun B, Michaels S, Young L, Duvoisin R, et al. Marijuana use among young black men who have sex with men and the HIV care continuum: findings from the uconnect Cohort. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51:1751–9.

Ostrow DG, Plankey MW, Cox C, Li X, Shoptaw S, Jacobson LP, et al. Specific sex drug combinations contribute to the majority of recent HIV seroconversions among MSM in the MACS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2009(51):349–55.

Marsden P. Models and methods in social network analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Gilman SE, Cochran SD, Mays VM, Hughes M, Ostrow D, Kessler RC. Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals reporting same-sex sexual partners in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:933–9.

The Social Organization of Sexuality. http://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/S/bo3626005.html. Accessed 25 May 2018

Cornwell B, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Graber J. Social Networks in the NSHAP Study: rationale, measurement, and preliminary findings. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64:i47–55.

Khanna AS, Michaels S, Skaathun B, Morgan E, Green K, Young L, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis awareness and use in a population-based sample of young black men who have sex with men. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:136–8.

Burt RS, Uniuersit C. Network items and the general social survey. Soc Netw. 1984;6:293–339.

Li J, Valente TW, Shin H-S, Weeks M, Zelenev A, Moorthi G, et al. Overlooked threats to respondent driven sampling estimators: peer recruitment reality, degree measures, and random selection assumption. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:2340–59.

Giles KL, Royer TA, Elliott NC, Kindler SD. Development and validation of a binomial sequential sampling plan for the greenbug (Homoptera: Aphididae) infesting winter wheat in the southern plains. J Econ Entomol. 2000;93:1522–30.

Fujimoto K, Flash CA, Kuhns LM, Kim J-Y, Schneider JA. Social networks as drivers of syphilis and HIV infection among young men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2018;94:365–71.

Newman MEJ. Assortative mixing in networks. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;89:208701.

Newman MEJ. Mixing patterns in networks. Phys Rev E. 2003;67:026126.

Simon W. Sexual interactions and HIV risk: new conceptual perspectives in European research, edited by Luc Van Campenhoudt, Mitchell Cohen, Gustavo Guizzardi, and Dominique Hausser. Am J Sociol. 1998;103:1762–3.

Bajos N, Hubert M, Sandfort T. Sexual behaviour and HIV/AIDS in Europe: comparisons of national surveys. London: Routledge; 2014.

Marks G, Millett GA, Bingham T, Lauby J, Murrill CS, Stueve A. Prevalence and protective value of serosorting and strategic positioning among Black and Latino men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:325–7.

Haraldsdottir S, Gupta S, Anderson RM. Preliminary studies of sexual networks in a male homosexual community in Iceland. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:374–81.

Prestage GP, Hudson J, Down I, Bradley J, Corrigan N, Hurley M, et al. Gay men who engage in group sex are at increased risk of HIV infection and onward transmission. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:724.

Wei C, Raymond HF, Guadamuz TE, Stall R, Colfax GN, Snowden JM, et al. Racial/Ethnic differences in seroadaptive and serodisclosure behaviors among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:22–9.

Hemmige V, McFadden R, Cook S, Tang H, Schneider JA. HIV prevention interventions to reduce racial disparities in the United States: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1047–67.

Akers RL, Krohn MD, Lanza-Kaduce L, Radosevich M. Social learning and deviant behavior: a specific test of a general theory. In: McCord J, Laub JH, editors. Contemporary masters in criminology. Boston, MA: Springer; 1995.

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986.

Barrington C, Latkin C, Sweat MD, Moreno L, Ellen J, Kerrigan D. Talking the talk, walking the walk: social network norms, communication patterns, and condom use among the male partners of female sex workers in La Romana. Dominican Republic Soc Sci Med. 1982;2009(68):2037–44.

Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Impact of beliefs about HIV treatment and peer condom norms on risky sexual behavior among gay and bisexual men. J Commun Psychol. 2005;34:37–46.

Davey-Rothwell MA, Latkin CA. An examination of perceived norms and exchanging sex for money or drugs among women injectors in Baltimore, MD, USA. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:47–50.

Chernoff RA, Davison GC. An evaluation of a brief HIV/AIDS prevention intervention for college students using normative feedback and goal setting. AIDS Educ Prev Off Publ Int Soc AIDS Educ. 2005;17:91–104.

Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002;14:164–72.

Martens MP, Page JC, Mowry ES, Damann KM, Taylor KK, Cimini MD. Differences between actual and perceived student norms: an examination of alcohol use, drug use, and sexual behavior. J Am Coll Health J ACH. 2006;54:295–300.

Holt M, Lea T, Mao L, Kolstee J, Zablotska I, Duck T, et al. Community-level changes in condom use and uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by gay and bisexual men in Melbourne and Sydney, Australia: results of repeated behavioural surveillance in 2013–17. Lancet HIV. 2018;5:e448–56.

Jeffrey AK, Yuri AA, Elena K, Sylvia V, Boyan V, Timothy LM, et al. Prevention of HIV and sexually transmitted diseases in high risk social networks of young Roma (Gypsy) men in Bulgaria: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;333:1098.

Fujimoto K, Williams ML, Ross MW. A network analysis of relationship dynamics in sexual dyads as correlates of HIV risk misperceptions among high-risk MSM. Sex Transm Infect. 2015;91:130–4.

Wasserheit JN, Aral SO. The dynamic topology of sexually transmitted disease epidemics: implications for prevention strategies. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(Suppl 2):S201-213.

Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences: international differences in work-related values. New York: SAGE; 1984.

Beloukas A, Psarris A, Giannelou P, Kostaki E, Hatzakis A, Paraskevis D. Molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 infection in Europe: an overview. Infect Genet Evol J Mol Epidemiol Evol Genet Infect Dis. 2016;46:180–9.

Henry DB, Kobus K, Schoeny ME. Accuracy and bias in adolescents’ perceptions of friends’ substance use. Psychol Addict Behav J Soc Psychol Addict Behav. 2011;25:80–9.

Prentice DA, Miller DT. Pluralistic ignorance and the perpetuation of social norms by unwitting actors. In: Zanna MP, editor. Adv exp soc psychol. Academic Press: New York; 1996. p. 161–209.

Goldstein MF, Friedman SR, Neaigus A, Jose B, Ildefonso G, Curtis R. Self-reports of HIV risk behavior by injecting drug users: are they reliable? Addict Abingdon Engl. 1995;90:1097–104.

Mulawa M, Yamanis TJ, Balvanz P, Kajula LJ, Maman S. Comparing perceptions with actual reports of close friend’s HIV testing behavior among urban Tanzanian men. AIDS Behav. 2016;20:2014–22.

Perkins JM, Nyakato VN, Kakuhikire B, Mbabazi PK, Perkins HW, Tsai AC, et al. Actual versus perceived HIV testing norms, and personal HIV testing uptake: a cross-sectional, population-based study in rural Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:616–28.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant R21 AI118998, Gilead Sciences (study number CO-GR-276-1695), and the Hellenic Scientific Society for the Study of AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. We would like to thank all study participants for the time and effort required to recruit their network members and participate in the interview. We would also like to thank Checkpoint Athens for the facilities and resources utilized in interviews.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All protocols and policies for this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Chicago, the Hellenic Scientific Society for the Study of AIDS and STDs, and the Scientific Council of Laiko General Hospital of Athens. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Institutional Review Boards of participating institutions approved all research activities related to this study. We obtained written informed consent from all survey respondents. Respondents were educated about HIV prevention during the intervention and were connected to appropriate health care or other supportive services when needed.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bowman, B., Psichogyiou, M., Papadopoulou, M. et al. Sexual Mixing and HIV Transmission Potential Among Greek Men Who have Sex with Men: Results from SOPHOCLES. AIDS Behav 25, 1935–1945 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03123-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03123-6