Abstract

Deciding to test for HIV is necessary for receiving HIV treatment and care among those who are HIV-positive. This article presents a systematic review of quantitative studies on relationships between psychological (cognitive and affective) variables and HIV testing. Sixty two studies were included (fifty six cross sectional). Most measured lifetime testing. HIV knowledge, risk perception and stigma were the most commonly measured psychological variables. Meta-analysis was carried out on the relationships between HIV knowledge and testing, and HIV risk perception and testing. Both relationships were positive and significant, representing small effects (HIV knowledge, d = 0.22, 95 % CI 0.14–0.31, p < 0.001; HIV risk perception, OR 1.47, 95 % CI 1.26–1.67, p < 0.001). Other variables with a majority of studies showing a relationship with HIV testing included: perceived testing benefits, testing fear, perceived behavioural control/self-efficacy, knowledge of testing sites, prejudiced attitudes towards people living with HIV, and knowing someone with HIV. Research and practice implications are outlined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

HIV testing is a prerequisite for receiving HIV treatment and care among those who are HIV-positive. Early diagnosis and access to treatment is associated with a reduced likelihood of onward transmission [1], better response to antiretroviral treatment (ART), and reduced mortality and morbidity [2]. However, many people living with HIV are unaware of their status. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that less than half of those infected with HIV have been diagnosed [3]. The growing availability of ART reinforces the need to scale up testing interventions. To develop interventions that are effective in increasing uptake, it is crucial to study the factors that may influence the decision to test [4].

Current WHO recommendations state that all HIV testing should be informed, voluntary and confidential [5]. Historically, voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) has been the dominant model, with individuals actively seeking an HIV test from a healthcare or community facility [6]. Client or self-initiated testing has been the main focus of increasing access initiatives, including through the use of mobile VCT centres [7] and home-based counselling and testing [8], which address testing barriers such as travel costs and confidentiality concerns [9].

Greater provider-initiated, routine, testing was recommended by the WHO in 2007 as an additional strategy to increase testing uptake [10]. This involves healthcare providers offering HIV testing to individuals attending facilities as a standard component of medical care (e.g., antenatal care), with the individual actively ‘opting out’ if they do not want to be tested [10]. However, while it is recommended that testing be routinely offered to groups with specific risk factors (e.g., in sexual health clinics in all contexts), it is not cost-effective to offer testing to all individuals presenting to health services unless in generalised epidemic settings [10]. Indeed, the WHO recommends a strategic mix of different models of testing delivered by a range of providers, including lay providers [5]. There remain, therefore, a significant proportion of the HIV positive population whose diagnosis is still reliant on uptake of VCT. Recent self-testing initiatives have further highlighted the importance of individual psychological factors related to HIV testing decision-making [11].

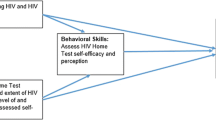

Social cognition models, including the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [12] and the Health Belief Model (HBM) [13], have highlighted the importance of individual proximal determinants of health behaviour. Many of these models, including the TPB, suggest that the likelihood of performing a given behaviour is dependent on the strength of intention to perform the behaviour, which, in turn, is influenced by other psychological factors (such as behavioural attitudes) [12]. For example, with reference to the TPB, behavioural HIV testing attitudes might include beliefs about the benefits of testing (e.g., “HIV testing helps people to access medication if they are HIV-positive) or the cons of testing (e.g., “HIV testing is not confidential”). The relationship between psychological factors and testing is potentially moderated by non-psychological factors, such as testing context (i.e., client vs. provider-initiated), regional resource availability and the nature of the population. For example, it may be that differing levels of HIV risk perception between MSM and heterosexual populations are important in explaining differences in HIV testing uptake [14]. Researching demographic and structural associations with testing is necessary for targeting interventions to appropriate populations [15, 16]. It is, however, also crucial to understand psychological factors that are associated with the decision to test or not to test for HIV, as these factors are likely to mediate the relationships between higher level factors (interpersonal and extrapersonal) and testing, are more proximal to testing decision-making and are potentially modifiable. This review focuses on associations between psychological factors and HIV testing.

Previous reviews of psychological associations with HIV testing have often focused on resource-rich contexts. In one review [17], studies were limited to high-income countries, with 34/50 (68 %) studies from the U.S.A. A second review [18] only included studies conducted in Europe. Grey literature (unpublished literature including dissertations and conference abstracts) was omitted from both of these reviews. A third recent review focused on intrapersonal, interpersonal and extrapersonal barriers to testing in Australia, Canada and the UK [19]. These reviews are helpful in starting to understand psychological factors that are associated with the decision to opt for or against HIV testing, and they highlighted important issues in relation to testing such as the fear of death and personal risk perception [18]. It is not possible, however, to conclude that correlates of testing will be similar in resource rich and resource limited contexts. For example, the nature of the relationship between HIV risk perception and HIV testing may be different in contexts where there are differing levels of accessibility to HIV care and treatment. This review, therefore, has no regional restrictions. This study also fills an important gap in the literature by conducting meta-analyses of the statistical relationships between psychological factors and HIV testing where there are enough studies to support this approach. This has not been conducted in other reviews [17, 18, 20]. Inclusion of meta-analyses means that the magnitude of effects can be evaluated [21]. In comparison with previous reviews [17–19], this article focuses only on studies that assess the quantitative relationships between psychological variables and testing (rather than combining quantitative and qualitative findings) to facilitate assessment of the strength of relationships with HIV testing. The main objective of this review, therefore, is to critically analyse and synthesise data from a comprehensive range of studies investigating the quantitative relationship between psychological (cognitive and affective) variables and HIV testing.

Method

Study Eligibility Criteria

This study followed PRISMA Statement guidelines [22] for the reporting of systematic reviews. Studies were included if they:

-

(1)

Used a quantitative design;

-

(2)

Included participants who had the capacity to make a decision to test for HIV. Studies of populations requiring parental/guardian consent to undergo an HIV test (e.g. children under the age of 15 or with profound learning disabilities), or for whom HIV testing was mandatory (e.g. some state prisoners in the U.S.A.) were excluded. The target population of this review was therefore predominantly individuals aged ≥15 years;

-

(3)

Measured psychological variables. Studies that focused explicitly only on psychological responses to HIV testing (such as measuring mood directly after testing) were excluded. ‘Psychological’ variables were more specifically defined as cognitive and affective variables, relating to an individual’s internal state (e.g. feelings or beliefs); and

-

(4)

Measured whether an HIV test was taken or not, according to self-report or patient records. Because it was considered unlikely that most studies would specify the mode of testing, for example, whether it was client-initiated (where the focus of the decision was whether to opt for or against testing), or provider-initiated (where the decision was whether to accept an offer or opt out of testing), all modes of testing were included.

Sources of Information

Studies published in peer-reviewed journals were retrieved from the electronic databases Pubmed/Medline, PsycINFO, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library. In addition, the search included papers from conference proceedings (International AIDS conference, AIDS Impact, International AIDS Society Conference), and the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD). The search was restricted to studies conducted since January 1, 1996. This was due to biomedical advances in 1996, which led to the uptake of effective antiretroviral regimens that have greatly improved the health and life expectancy of people with HIV/AIDS. Any studies using data collected before this date were excluded.

Search Strategy

The searches were conducted using combinations of the following terms: ‘HIV testing’, ‘psychological’, ‘psychosocial’, ‘psychiatric’, ‘cognitive’, ‘affective’, ‘behavioural (behavioral)’, ‘psychopathology’, ‘mood’, ‘beliefs’, ‘illness perception’ and ‘illness representation’. ‘HIV testing’ was searched for as a keyword in the title, whereas the psychological terms were searched for as keywords in the title or abstract.

Data Collection

Following recommendations of PRISMA [22], the data collection process had four stages (see Fig. 1). One reviewer (KP) carried out the searches for the identification of studies, using pre-specified search criteria. This was completed on 1st October 2014. All duplications were removed. Two reviewers (KP and one of two undergraduate reviewers) independently screened the remaining titles and abstracts for eligibility. Articles considered relevant by either reviewer were retrieved in full text. The two reviewers then independently assessed eligibility of the retrieved articles. Exclusions were reported, with reasons given. Any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (ME or AW), to result in a final group of studies for analysis.

Data Abstraction and Quality Assessment

The following details were extracted from the articles (by KP, verified by ME): authors, date of publication, location, design, nature of sample, age, gender, ethnicity, definition and measurement of psychological and testing variables, context and measurement of testing behaviour, and nature of relationship between psychological variables and testing. Methodological quality was assessed, using criteria adapted from Siegfried et al. [23]. Articles were assessed on two dimensions of external validity (sample representativeness and response rate) and four dimensions of internal validity (performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias and selection bias/confounding) (see Table 1).

KP and one undergraduate reviewer assessed all articles independently, before comparing ratings. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between KP and the undergraduate reviewer. Ongoing disagreement was resolved by ME or AW.

Statistical Analysis

Inter-rater reliability for study eligibility was assessed using Cohen’s Kappa. Meta-analyses were conducted on the associations between selected psychological variables and HIV testing. A minimum of 15 studies measuring the association between a specific variable and testing was required for eligibility for meta-analysis, based on evidence of bias with the use of meta-analysis with small numbers of studies [24]. Effect sizes (either standardised mean differences [d] or odds ratios [OR]) were calculated for the relationship with testing for each study sample. The use of either d or OR in each meta-analysis was determined by data provided by the majority of studies (e.g., the majority of studies measuring HIV knowledge used d, hence the few studies that that used OR were converted to d [25]). If any data were missing, authors were contacted to supply the information. R-3.1.2 (http://www.r-project.org/) was used to conduct the meta-analyses and assess heterogeneity, outliers and influence, and publication bias. Random effects models were used as there could be no assumption the samples were drawn from a homogenous population. Further permutation tests were run due to the small number of studies included in each meta-analysis [26]. Cochran’s Q test (testing differences between study effect sizes) and the I 2 test [27] (measuring the extent of inconsistency among study effect sizes) were used to test for heterogeneity between studies (with I 2 values 25, 50 and 75 % equivalent to low, moderate and high levels of inconsistency [28]).

Publication bias was assessed using both Rosenberg’s Fail-Safe N [29] and the trim and fill method [30]. Rosenberg’s Fail-Safe N estimates the number of non-significant unpublished studies required to eliminate a significant overall effect size. Fail-Safe numbers do not take into account sample size or variance of the studies, however. Therefore, the trim and fill method was also used. This method tests and adjusts for funnel plot asymmetry that may be caused by studies with small samples showing small effects being less likely to be published than similar sized studies showing larger effects.

Results

Study Characteristics

The search identified 62 studies eligible for inclusion (see Fig. 1).

There was strong agreement between the reviewers on eligibility (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.85, p < 0.001). Thirty-six articles were published between January 2010 and October 2014 [31–66], and 24 were published in 2000–2009 [67–90]. Only two articles published prior to 2000 were included [91, 92]. Twenty articles described research conducted in sub-Saharan Africa [34, 36–38, 47–51, 54, 58, 59, 62, 64, 67, 76, 77, 81, 85, 90]. Another 21 were conducted in North America [32, 35, 40, 42, 45, 55, 57, 61, 66, 68, 69, 71, 73, 74, 78, 80, 84, 86, 87, 91, 92], one in South America [93], and four in the Caribbean [33, 82, 83, 89]. Nine were conducted in Asia [39, 43, 44, 46, 52, 63, 65, 79, 88], five in Europe [41, 53, 60, 70, 72], and one in Australia [31]. One study [75] incorporated findings from both sub-Saharan African and Asian regions.

The majority of studies (n = 56) were cross-sectional (measuring both psychological factors and testing at the same time point) [31–44, 46, 47, 49–53, 56, 57, 59–70, 72–88, 90–92]. Forty-nine of the cross sectional studies asked about historical HIV testing (e.g., any lifetime testing) [31, 34–44, 46, 49–53, 56, 57, 59–70, 72, 73, 75–80, 82–84, 86–88, 90, 91], and seven measured whether testing was undertaken at the time of study [32, 33, 47, 74, 81, 85, 92]. There were four prospective cohort studies [45, 55, 58, 71], one case–control study [54], and one intervention study [48].

Testing context (client or provider-initiated) was not generally specified, with the exception of a few studies which restricted the outcome variable to VCT [43, 54, 88, 91]. One study [62] provided data for several testing outcomes, including client and provider-initiated testing. Prospective studies gave more detail on testing context. Two studies [58, 85] reported acceptance of antenatal testing, and three [33, 47, 92] specified ‘voluntary’ testing at the clinic or study site. A summary of the 62 selected studies is presented in Table 2.

Participants

Across all studies, there were 339,227 participants. Sample sizes were generally large (the largest sample size was 134,965 [38] ) and 28 studies had sample sizes of over 1,000 [36–39, 41, 44, 50, 51, 53, 56, 58, 60–62, 65, 68, 70, 71, 75, 78, 81–86, 90, 91]. Only one study [40] had a sample size below 100. There was a diverse range of target populations. Most studies had wide age ranges, with participants aged 15–60 years. Exceptions included one study that sampled high school students [70], seven that sampled university students [57, 61, 80, 86, 87, 89, 92], and two studies that sampled adults aged 50 and older [42, 91]. Other studies sampled populations at higher risk for HIV: two studies sampled intravenous drugs users (IDU) [40, 78], five sampled sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinic attendees [11, 52, 59, 67, 73, 74] sampled men who have sex with men (MSM) [31, 41, 43, 45, 46, 49, 55, 60, 63, 64, 66], two sampled female sex workers (FSW) [44, 51], and one sampled male clients of FSW [79]. One study sampled patients receiving care for tuberculosis [88], and two sampled women attending antenatal care [58, 85]. One study [78] included several high-risk groups in its analysis (IDU, MSM, heterosexual individuals recruited from gay bars, and STI clinic attendees). Two studies sampled inmates of correctional facilities [33, 69]. Gender ratios varied between studies, but there was an overall majority of male participants (approximately 55 %).

Twenty-eight studies reported the ethnicity of participants [32, 35, 40, 44–47, 49, 53, 55, 57, 59, 61, 64–67, 71–74, 77, 78, 80, 84, 86, 90, 92]. At least eight different ethnic groups were represented (African American, Black African, White, Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, Han Chinese, Non-Han Chinese and Native American).

Measurement of Testing Behaviour

Of the 56 cross-sectional studies, 49 (88 %) used self-report measures to assess testing [31, 34–44, 46, 49–53, 56, 57, 59–70, 72, 73, 75–80, 82–84, 86–88, 90, 91], with participants reporting whether they had tested for HIV. In the majority of studies (n = 34) [34, 36, 37, 39, 44, 46, 50, 51, 53, 56, 57, 59, 61–65, 67, 68, 70, 72, 73, 75–78, 80, 82, 83, 86–88, 90, 91], participants were asked to specify whether they had ‘ever’ been tested for HIV. Five studies asked participants to specify whether they had tested in the last 12 months or previously in their lifetimes [35, 41, 43, 49, 60]. Three studies asked participants if they had tested in the last 12 months [42, 48, 69], and two asked participants if they had tested in the last 6 months [52, 79]. Two studies asked participants if they had both been tested and returned for results [38, 84]. Three studies measured frequency of testing, either by summing the number of times participants had tested [40] or categorising testing as either ‘routine/non-routine’ or annual [31, 66].

Twelve studies assessed testing behaviour either at the time of study or during a specified follow-up period. In general these relied on clinical records, such as blood draws [32, 47, 81] or medical logs [33, 58, 74, 85], to establish testing behaviour. Exceptions included three prospective cohort studies [45, 55, 71] and one intervention study [48], which used self-report measures to assess whether participants had tested during follow-up, and one cross sectional study, which measured self-reported testing uptake at the time of the study [92].

Measurement of Psychological Factors

A number of studies used health behaviour theories to direct the measurement psychological variables, most commonly the Health Belief Model [32, 51, 80, 92]. There was considerable variation in the type of psychological variables measured across studies. These were grouped into variables specifically related to testing (e.g. perceived benefits and barriers to testing), HIV non-testing variables (e.g., HIV-related stigma, and HIV-related knowledge), sexual behaviour cognitions (e.g., peer sexual norms and attitudes towards condom use), general psychological variables (e.g., depression, self-esteem) and societal cognitions (e.g., perceived social support, institutional mistrust, and homosexuality-related stigma). Perceived HIV risk was the most commonly measured variable, in 28 studies [33, 40, 42, 44, 46–48, 52–54, 56, 57, 62–64, 69, 73, 79, 81–86, 89, 91, 94, 95]. HIV-related knowledge was measured in 25 studies [31, 33–35, 39, 42–44, 46, 48–50, 52, 56, 58, 61–63, 65, 67, 73, 77, 79, 83, 84]. Eighteen studies measured HIV-related stigma [31, 33, 34, 36, 38, 40, 41, 50, 51, 59, 62, 67, 75–77, 87, 90, 96].

Relationships Between Psychological Variables and Testing

Meta-analyses were carried out on the relationship between HIV testing and the variables of HIV-related knowledge and perceived risk of HIV, given the larger number of studies measuring these variables where data was available (>15 studies). Findings will be discussed in relation to individual psychological variables where these appeared in two or more studies.

HIV Testing-Related Psychosocial Variables

Perceived Benefits of Testing/Pro-testing Attitudes

The majority of studies showed positive relationships between perceived benefits of testing and testing behaviour. Of eight studies, six found a significant positive relationship with testing (previous testing or test acceptance on the same day). These six studies sampled from varied populations, two [31, 41] were conducted with MSM, two [92, 97] with university students, one with prisoners [69] and one [77] with residents of a peri-urban setting in South Africa. One study [32] that found a non-significant relationship between perceived benefits and testing measured test acceptance on the same day (with women who had experienced intimate partner violence). One study [51] found generally non-significant relationships between perceived benefits and testing, although men on worksites and low income women tested less if they perceived testing to be useful in HIV-negative individuals. Only two of these eight studies took place in sub-Saharan Africa [51, 77].

Perceived Barriers to Testing/Cons of Testing

Five of the eight studies which measured perceived barriers to testing found an association with testing in either univariate or multivariate analysis (lower perceived barriers significantly associated with previous testing) [31, 51, 57, 76, 80]. Five of the eight studies took place in resource rich contexts [31, 32, 57, 80, 92]. Studies assessed a range of barriers including uncertainty about confidentiality, fear of needles and perceived difficulty in obtaining an HIV test.

Perceived Accessibility and Knowledge of Testing Site

‘Knowledge of a testing site/services’ or perceived accessibility of testing site was measured (using a single item) in four studies [46, 52, 60, 76]. All four found highly significant positive relationships with previous testing with three of the four studies showing independent effects [46, 60, 76]. These studies took place in a variety of settings and with different populations.

Perceived Behavioural Control/Self-efficacy

Perceived behavioural control in relation to testing includes both internal and external control factors. Two studies [31, 43] (both with MSM) measured perceived behavioural control and found significant independent associations with previous testing. One study found a large independent effect of the related construct of testing self-efficacy on testing [98].

Perceived Norms of Testing

There were inconsistent relationships between perceived testing norms and testing. Four studies measured descriptive norms (beliefs about the testing attitudes and behaviour of others). Two studies found significant independent positive relationship between descriptive norms and previous testing, using single items [41, 59]. Two studies, however, failed to find relationships between descriptive norms and testing [75, 92]. One study [31] measured subjective/social norms (perceived social pressure to test). They found, in an MSM sample, a significant positive relationship between subjective norms (belief that friends would endorse the participant’s decision to test for HIV) and previous testing in univariate but not multivariate analysis.

Fear of Testing

Three studies [31, 77, 78] measured fear of testing. All three found significant negative associations with previous testing, although not in multivariate analysis in one study [31].

Intention to Test in the Future

Studies generally supported a positive relationship between intention to test, and testing behaviour. Four studies measured intention to test for HIV in the future. Three [35, 43, 58], observed an effect on testing, although one study only found a univariate and not a multivariate effect [35]. One of these was a prospective cohort study [58] with women attending antenatal care, the other two [35, 43] measured testing behaviour retrospectively. The fourth study [76], carried out with Tanzanian school teachers, showed a non-significant relationship between intention and testing.

Non Testing HIV-Related Psychosocial Variables

HIV-Related Knowledge

Of the 25 studies measuring HIV-related knowledge, 14 found a significant positive association with testing [31, 34, 35, 39, 43, 46, 49, 50, 52, 56, 58, 61, 62, 84]. One [61] found a significant association among female but not male participants. A random effects meta-analyses found a small [99] positive association between HIV-related knowledge and lifetime testing (d = 0.22, 95 % CI 0.14–0.31, p < 0.001). A similar level of significance was found using permutation testing (p = 0.002). Significant heterogeneity was found across studies (I 2 = 77.28 %, Q = 75.75, p < 0.001, see Fig. 2).

The association between HIV knowledge and testing was not moderated by high income versus low/middle income study setting (p < 0.46). One outlier [56] was identified from the meta-analysis. Removal of this study from the model resulted in minimal change (d = 0.20, 95 % CI 0.12–0.27, p < 0.001). There was little evidence of publication bias (Rosenberg’s Fail-Safe N = 479), with the trim and fill method estimating only one missing study was contributing to funnel plot asymmetry.

Perceived Risk of HIV

A distinction was made between studies measuring participants’ perceived risk of currently being HIV-positive (n = 3) [33, 46, 47], participants’ perceived risk of acquiring HIV in the future (n = 15) [40, 42, 44, 51, 62, 63, 69, 72, 79, 82–84, 86, 91, 100], and studies where it was unclear if the measure referred to current or future risk (n = 10) [48, 52–54, 56, 57, 64, 73, 81, 85]. Of three studies measuring participants’ perceived risk of currently being HIV-positive, one study [33] found a significant positive association with testing and two did not [46, 47]. Of the 15 studies measuring participants’ perceived risk of contracting HIV in the future, eight found significant positive relationships with testing [40, 62, 72, 82–84, 86, 91], one of these only in women and not in men [72], and one more frequently for provider-initiated than client-initiated testing [62]. One study [51] found a significant negative association between perceived risk and testing (among female sex workers only). Of the ten studies that did not specify whether they were measuring either present/future perceived risk, four found a significant positive association with testing [52, 53, 56, 57]. Two [52, 53] of these found significant associations among male, but not female participants.

Due to the relatively small number of studies for each of the risk variables and the conceptual similarity in measurement, all measures of perceived risk (current/future/unknown) were included in the same meta-analysis. A small positive association was found between perceived risk of HIV and lifetime testing using a random effects meta-analysis model (OR 1.47, 95 % CI 1.26–1.67, p < 0.001). A similar level of significance was found using permutation testing (p = 0.002). There was significant heterogeneity across studies (I 2 = 92.01 %, Q = 369.07, p < 0.001, see Fig. 3).

The association between risk perception and HIV testing was not moderated by high income versus low/middle income study setting (p = 0.19). One outlier [91] was identified from the meta-analysis. Its removal did not significantly affect the model (OR 1.38, 95 % CI 1.23–1.53, p < 0.001). There was no evidence of publication bias (Rosenberg’s Fail-Safe N = 15,207), with the trim and fill method estimating zero studies were missing from the left side of the funnel plot.

HIV-Related Stigma

Earnshaw and Chaudoir’s HIV stigma framework [101] was used to categorise the different measures of stigma used.

Prejudiced attitudes Ten studies measured prejudicial attitudes towards people living with HIV (PLWH) [34, 36, 38, 40, 50, 51, 59, 62, 77, 88]. Five studies found that holding prejudicial attitudes was significantly associated with lower uptake of previous testing [38, 50, 59, 77, 88]. A further two studies found some associations between attitudes towards PLWH and HIV testing [34, 36]. The studies measuring prejudiced attitudes covered a variety of populations and contexts.

Discrimination Discrimination against PLWH was measured in four studies [40, 59, 62, 90]. One of these studies [62], using data from a population-based survey in Zimbabwe, found a significant negative association (for both client and provider-initiated testing) among female, but not male participants. The other three studies failed to show an effect [40, 59, 90].

Anticipated stigma Anticipated stigma if diagnosed HIV-positive or testing for HIV was measured in three studies. Two studies failed to show an effect with testing [33, 62]. One study found that anticipated stigma was associated with an absence of testing in univariate but not multivariate analysis [76].

Mixed measures of stigma There were two studies where the stigma measures could not be categorised according to the Stigma Framework [101] (due to the use of scales which combined items from across categories). One study found that stigma was associated with an absence of testing in univariate but not multivariate analysis [31]. The second study found that stigma was associated with lower levels of testing in Thailand but not in African sites [75].

Meta-analysis was not carried out on the relationship between HIV stigma and HIV testing due to the small number of studies measuring each distinct stigma process.

Perceived Susceptibility to HIV

There was inconsistent evidence on the relationship between perceived susceptibility and testing. Of seven studies measuring perceived susceptibility to HIV, two [32, 80] found a significant positive association with testing. One study [37] found higher perceived susceptibility was significantly associated with less likelihood of previous testing. The four studies with non-significant findings [31, 45, 76, 92] assessed a variety of populations including MSM, college students, and school teachers.

Perceived Severity of HIV

There was no evidence supporting a relationship between perceived severity of HIV and testing. Of the three studies [31, 32, 92] measuring perceived severity of HIV, none found a significant relationship with testing.

Fear of HIV Infection

Two studies [41, 43] measured fear of contracting HIV. Both found increased fear of HIV was independently significantly associated with decreased likelihood of testing. Both studies were conducted with MSM.

Belief in HIV-Related Conspiracy Theories

There was contradictory evidence on the direction of the effect for belief in conspiracy theories and testing. Four studies measured belief in HIV-related conspiracy theories. Two studies [42, 68] found that holding conspiracy beliefs was associated with a greater likelihood of testing. Two studies [64, 67] found significant negative associations with testing.

Knowing Someone with HIV

Of eight studies which asked whether participants knew someone with HIV (two studies [70, 83] specifically asking if the participant had a friend or relative with HIV), six [69, 70, 82, 83, 90, 100] reported a significant independent positive relationship between knowing someone with HIV and testing. These studies took place in different contexts and with different populations.

Sexual Behaviour Cognitions

Peer Sexual Norms

One study [65] measuring perceived peer sexual risk-taking, found a significant positive association with previous testing. One study [72] measuring descriptive norms of using condoms with new partners, found that lower perceived norms was associated with less likelihood of previous testing.

Attitudes to Condom Use

Neither of the two studies [64, 79] measuring attitudes towards condom use found a significant relationship with testing.

Sexual Self-efficacy/Sexual Locus of Control

Two studies [34, 37] measured self-efficacy for HIV preventative behaviours, in African populations. Both found a significant positive relationship with previous testing using multi-item scales. One study [61] in the US measuring participants’ locus of control for sexual activities found that greater internal control was associated with a higher likelihood of testing.

General Psychological Variables

Depression

There was conflicting evidence on the effect of depression on testing. Of three studies measuring depression [61, 65, 68] one [68] found a significant negative association, and one [65] found a significant positive association with previous testing.

Coping Mechanisms

Two studies [74, 84] measured coping mechanisms in response to stressors. One study found that problem-focused/positive coping strategies were positively associated with testing [84]. The second study [74] did not find any relationship between coping and testing.

Self-efficacy for Handling Difficult Situations

Of two studies [32, 48] measuring self-efficacy for the general handling of difficult situations, neither found a significant relationship with testing.

Perceived Health Status

Of the two studies which measured the self-perceived health of the participants, one study in Tanzania [76] found that those with more positively-rated health status had a higher likelihood of testing. The other in Eastern Europe [70] found that participants with more poorly rated health status had a higher likelihood of previous testing.

Societal Cognitions

Perceived Social Support

Of the two studies [33, 53] measuring perceived social support, neither found a significant relationship with testing.

Institutional Mistrust/Perceived Discrimination

Three studies measured different aspects of institutional mistrust. Two found a significant negative association between previous testing and beliefs in systematic discrimination [45], and government mistrust [42]. One study [74] found a positive association between perceived racism and testing.

Homosexuality-Related Stigma

Three studies measured internalised homophobia. One [49] found a significant negative association with previous testing, two failed to show an effect [66, 98]. One study [66] also measured openness of homosexuality and found a significant positive association with previous testing. Sexual orientation-based discrimination/stigma was measured by four studies [43, 49, 63, 66]. Only one study showed a relationship between discrimination and testing [43].

Methodological Quality

The methodological quality of studies is summarised in Table 3. A tick (✔) signifies that the criterion was met. A cross (x) indicates that the criterion was either not met or it was unclear if the criterion was met.

External Validity

Twenty-three of the 62 studies used random sampling [33, 34, 36–39, 41, 42, 44, 48, 50, 51, 53, 54, 56, 62, 69, 70, 75, 81, 82, 90, 91], and 33 used consecutive sampling methods [31, 32, 35, 40, 43, 45–47, 49, 52, 55, 57–60, 63–68, 72–74, 76–78, 80, 83, 85, 86, 92, 100] (see Table 3). Six studies did not specify the sampling method used [61, 71, 79, 84, 87, 88]. Twenty-three studies reported response rates [31, 33, 38–41, 43, 44, 51–53, 56, 58, 62, 63, 69, 72–74, 76, 84, 85, 88], with 16 studies specifying that at least 80 % of those eligible to participate were recruited [33, 38, 39, 43, 51, 56, 58, 62, 63, 69, 73, 74, 76, 84, 85, 88]. Only seven studies met both criteria for external validity [33, 38, 39, 51, 56, 62, 69].

Internal Validity

Eight studies measured testing objectively, using the provision of a blood specimen at the time of study, or clinic records [32, 33, 47, 58, 74, 81, 85, 92]. Thirty-five studies measured psychological variables using methods of established reliability and validity [31–33, 35–37, 39, 40, 42, 45, 46, 48, 49, 52, 53, 56, 57, 59, 61, 63–68, 71, 73–77, 80, 84, 87, 92]. Two of the four prospective cohort studies [58, 71] were free from attrition bias, reporting that at least 80 % of participants were present in the final analysis. One study [45] did not provide enough information for attrition rate to be established. One prospective cohort study [55] and the intervention study [48] reported attrition rates of over 20 %. Forty-nine studies carried out multivariate analyses to control for potential confounding variables [31–33, 35–39, 41–51, 53, 54, 56, 58–72, 74, 76, 77, 80, 82, 83, 87, 90–92, 100]. In total, only four of the 62 studies provided evidence of meeting all criteria for internal validity [32, 33, 74, 92].

Discussion

This review aimed to synthesise and analyse data from studies investigating the relationship between psychological variables and HIV testing. Sixty-two studies were included. The most commonly measured variables were either directly related to HIV testing (e.g., perceived benefits of and barriers to testing) or HIV non-testing related variables (e.g., HIV knowledge). In general, there appeared to be larger effects for proximal testing-related variables (e.g., HIV testing fear) than for more distal variables (e.g., depression). The generally large sample sizes suggest that a lack of statistical power is an unlikely explanation for many of the small effects reported.

Many HIV-testing related variables included in studies are featured in health behaviour models [102–104]. Perceived benefits of testing were associated with HIV testing in the majority of studies which assessed this variable, with strong independent relationships across different populations and contexts [31, 69, 77, 92]. There were inconsistent findings, however, of the effects of perceived barriers or cons of testing. Assessing the effect of this variable on testing is complex partly because it has been measured as both a multi-dimensional construct [51] and as its individual components (e.g., testing fear, anticipated stigma, perceived accessibility of testing). Perceived behavioural control or testing self-efficacy were infrequently measured. All three studies that measured these variables found significant positive relationships with testing [31, 43, 60]. There were mixed findings in relation to normative beliefs. Descriptive norms (beliefs about the testing attitudes and behaviour of others) were more frequently measured than subjective norms (perceived social pressure to test). This is despite the fact that descriptive norms do not appear in the most commonly used health behaviour models, in contrast to subjective norms [102]. Intention to test in the future was only independently associated with HIV testing in two of four studies [43, 58]. It is likely that a number of other factors, including some of those reported in this review, are associated with the likelihood of intention being enacted. For all of the above constructs, very few studies were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa and the majority used scales with five items or fewer.

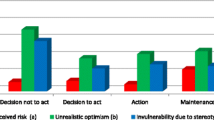

Fear of testing was significantly associated with testing in all three studies, in different populations, where this was assessed [31, 77, 78]. Fear of HIV infection also showed negative relationships with HIV testing (in two studies) consistent with the effect of fear of HIV testing [41, 43]. These findings are in contrast to the lack of an effect of perceived severity of HIV despite the latter factor appearing in some health behaviour models [104, 105]. It may be that other aspects beyond HIV severity contribute to fear responses. Emotional factors are rarely directly included in health behaviour models with some exceptions [106, 107]. The small number of studies where fear was measured may underplay its significance in the HIV testing context. The fear findings are consistent with conceptualising HIV testing as a detection behaviour associated with significant personal risks. Prospect Theory [108] states that people are fundamentally risk averse and in certain situations (perhaps when the outcome of the behaviour is uncertain) people will choose not to act rather than face the risk of a negative outcome if they engage in the target behaviour (e.g., testing positive for HIV as a result of taking an HIV test).

Small positive associations between perceived HIV risk and HIV testing (and between HIV knowledge and HIV testing) across different populations and contexts were found, consistent with potential distal effects. The relationship between perceived HIV risk and HIV testing is difficult to interpret given measurement ambiguity. In some studies, HIV risk referred to beliefs about currently being HIV positive. More commonly, HIV risk referred to an estimation of the likelihood of becoming HIV positive in the future (very similar to perceived susceptibility). In many studies, it was unclear whether the measure referred to current or future risk perception or whether the authors intended to distinguish the variable from perceived susceptibility. It may be that there are different relationships between current HIV risk and testing and future HIV risk (or susceptibility) and HIV testing. Many models of health behaviour include the construct of HIV risk perception or susceptibility [13, 105, 109, 110], with the effect of risk perception or perceived health threat sometimes thought to be mediated by appraisal and coping processes [106].

HIV-related stigma was measured in many studies (using multi-item scales), despite its lack of inclusion in the most commonly used health behaviour models. We used an HIV stigma framework [101] to organise findings but it remained difficult to clarify the intended nature of many measures. The strongest effect appeared to be a negative relationship between prejudiced attitudes towards PLWH and HIV testing. Other aspects of HIV stigma (discrimination against PWLH and anticipated stigma) or mixed measures of stigma appeared to be less strongly related to HIV testing.

There was an effect of knowing someone with HIV on testing. If the known person with HIV was a sexual partner, this may have triggered HIV testing, consistent with the impact of social messages on illness representation [106] or as a cue to action [104]. As studies tended to ask a single question to assess this variable, it was not possible to ascertain whether the identity of the known person had an effect on testing. In addition, given the historical nature of the outcome variable in many studies, the direction of possible causation is unclear.

The relationship between higher levels of sexual self-efficacy/sexual locus of control and greater rates of HIV testing in all three studies where this was measured [34, 37, 61] was surprising. This factor does not appear in health behaviour models. It may be that this aspect of self-efficacy is conceptually related to HIV testing self-efficacy/perceived behavioural control, which has been invoked in health behaviour models.

Strengths and Limitations of the Review

One of the main strengths of the review was its broad inclusion criteria. This was reflected in a comprehensive search strategy which included peer-reviewed journals and grey literature, with no regional and few population restrictions. The wide range of participant characteristics in the included studies enhances external validity and potentially allows one to assess whether these characteristics moderate the relationship between psychological factors and HIV testing. The use of meta-analysis in this context is novel, as is the use of permutation tests [111] to corroborate the findings from random effects models, given the relatively small number of studies included. Some moderator analysis was conducted, although there was only sufficient data available to examine one moderator (country income level) on the relationships between risk perception and testing, and HIV knowledge and testing. It will be important for future studies to be able to determine whether the relationship between a wider range of psychological variables and HIV is moderated by study location. For example, there may be differences in whether fear about testing influences testing uptake in different contexts.

It was not possible to carry out meta-analysis on a wider range of variables. Therefore, it cannot be concluded that those variables where the majority of studies show a significant relationship with testing equates with pooled estimates that show significant testing effects. As more studies are carried out, researchers will be able to carry out such analysis as well as moderation analysis of significant power to be able to detect significant effects for a range of potential moderators (e.g., sex, provider versus initiator testing, sexual preference) [112]. We used multiple methods of assessing potential publication bias, although we acknowledge limitations with existing techniques [113]. A further limitation of the review related to the grouping of independent variables. There was considerable variation in measures and terminology used. The Theoretical Domains Framework was considered as a tool to organise independent variables but this was rejected as the Framework appeared to be at too high a level of abstraction to capture the complexity of measures used [114]. Inevitably, with many overlapping constructs and with some measures of uncertain reliability and validity, this may have influenced the nature and magnitude of summarised effects. In particular, it may be that combining risk perception measures in the same meta-analysis may have obscured the effects of current versus future risk perception. This review did not examine relationships between models in their entirety and testing, although the findings on individual variables suggest that current models might require modifications for them to be applied validly to HIV testing contexts.

Research Implications

An important limitation of studies that aimed to answer questions about associations between psychological factors and HIV testing was the retrospective measurement of HIV testing. Examining the relationship between current psychological variables and lifetime HIV testing complicates casual inferences. For example, it may be that people’s perceptions of their risk of HIV (current or future), or their perceived benefits of HIV testing are post hoc rationalisations of the outcome of previous HIV testing. It would be helpful for more studies to use prospective designs to examine relationships between psychosocial variables and HIV testing. Only one intervention study [115] was included in this review as, typically, testing interventions did not measure associations between potentially mediating psychological variables and testing. Doing so would be helpful to establish the causal mechanism of interventions. It would also be useful for studies to clarify whether testing took place as a result of a client or provider-initiated process.

Most studies measured cognitions in contrast to assessing emotions. It would be useful to see a greater emphasis on measuring emotions (e.g., anxiety and guilt), particularly given the associations seen between fear and HIV testing. Regarding variables that were measured, we suggest that testing benefits and barriers, perceived behavioural control (along with other aspects of self-efficacy such as sexual self-efficacy), and normative beliefs be included more frequently in future studies. We argue that using multi-item scales to measure these constructs [116, 117] are likely to be more reliable and valid that the briefer scales that are more commonly used. We also suggest that such work be carried out in sub-Saharan Africa, given the limited research on these factors in this context. Both current and future risk perception could be assessed in the same study in the future and they should be distinguished and clearly defined. In addition, it would also be useful to ask separately about individuals whom participants know are HIV-positive.

Practice Implications

This review did not directly assess interventions to increase HIV testing and, in general, interventions have not assessed their effects on mediating psychological variables. Hence, any practice implications must be expressed cautiously. At the most, we can only suggest variables that could be both be targeted in interventions and measured as potential mediators of the effects of interventions on HIV testing.

On the basis of the evidence in this review, it would seem fruitful to focus on interventions that emphasise the benefits of testing, enhance testing self-efficacy, provide information on testing sites, minimise HIV testing fear, decrease prejudice towards PLWH and increase personal contact with PLWH. Interventions targeting these factors can be delivered at a range of levels. That is, change at higher levels could facilitate change in proximal psychological determinants of testing. At the individual level, approaches such as motivational interviewing (with the aim of supporting self-efficacy and building on the individual’s perceived benefits for testing) have been used with some success [118–120]. At the social/relational level, peer education may also help to change testing attitudes and self-efficacy as well as providing information on testing availability. Peer education has been used successfully to enhance HIV testing rates [121]. At the population level, mass media and social marketing approaches may influence similar testing determinants. Both have been used with some evidence of enhanced HIV testing rates [122–124]. Finally, structural approaches to increase the availability, acceptability and accessibility of HIV testing, may influence intrapersonal psychological factors. There is considerable evidence of the effectiveness of structural approaches such as rapid, provider-initiated, mobile and home testing in enhancing HIV testing rates [125–128].

References

Fox J, White PJ, Macdonald N, et al. Reductions in HIV transmission risk behaviour following diagnosis of primary HIV infection: a cohort of high-risk men who have sex with men. HIV Med. 2009;10(7):432–8.

Egger M, May M, Chene G, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360(9327):119–29.

WHO. Global update of the health sector response to HIV, 2014. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2014.

WHO/UNAIDS. Service delivery approaches to HIV testing and counselling (HTC): a strategic programme framework. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2012.

WHO. Consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2015.

van Rooyen H, McGrath N, Chirowodza A, et al. Mobile VCT: reaching men and young people in urban and rural South African pilot studies (NIMH Project Accept, HPTN 043). AIDS Behav. 2013;17(9):2946–53.

Matovu JK, Makumbi FE. Expanding access to voluntary HIV counselling and testing in sub-Saharan Africa: alternative approaches for improving uptake, 2001-2007. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12(11):1315–22.

Wolff B, Nyanzi B, Katongole G, Ssesanga D, Ruberantwari A, Whitworth J. Evaluation of a home-based voluntary counselling and testing intervention in rural Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2005;20(2):109–16.

Jurgensen M, Sandoy IF, Michelo C, Fylkesnes K, Mwangala S, Blystad A. The seven Cs of the high acceptability of home-based VCT: results from a mixed methods approach in Zambia. Soc Sci Med. 2013;97:210–9.

WHO/UNAIDS. Guidance on provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling in health facilities. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2007.

Johnson C, Baggaley R, Forsythe S, et al. Realizing the potential for HIV Self-testing. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:S391–5.

Ajzen I. From intentions to action: A thoery of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J, editors. Action-control: from cognition to behavior. Heidelberg: Springer; 1985. p. 11–39.

Rosensto IM. Historical origins of health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2(4):328–35.

Moneyham L, Murdaugh C, Phillips K, et al. Patterns of risk of depressive symptoms among HIV-positive women in the southeastern United States. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2005;16(4):25–38.

Andrews B. Sociodemographic and behavioural characteristics of youth reporting HIV testing in three Caribbean countries. West Indian Med J. 2011;60(3):276–83.

Jin FY, Prestage G, Law MG, et al. Predictors of recent HIV testing in homosexual men in Australia. HIV Med. 2002;3(4):271–6.

de Wit JB, Adam PC. To test or not to test: psychosocial barriers to HIV testing in high-income countries. HIV Med. 2008;9(Suppl 2):20–2.

Deblonde J, De Koker P, Hamers FF, Fontaine J, Luchters S, Temmerman M. Barriers to HIV testing in Europe: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(4):422–32.

Bolsewicz K, Vallely A, Debattista J, Whittaker A, Fitzgerald L. Factors impacting HIV testing: a review—perspectives from Australia, Canada, and the UK. AIDS Care. 2015;27(5):570–80.

Gari S, Doig-Acuna C, Smail T, Malungo JRS, Martin-Hilber A, Merten S. Access to HIV/AIDS care: a systematic review of socio-cultural determinants in low and high income countries. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:198.

Fagard RH, Staessen JA, Thijs L. Advantages and disadvantages of the meta-analysis approach. J Hypertens Suppl. 1996;14(2):S9–12 discussion S13.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, Volmink J. Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD003362.

Kulinskaya E, Morgenthaler S, Staudte RG. Combining statistical evidence. Int Stat Rev. 2014;82(2):214–42.

Lipsey MW, Wilson D. Practical meta-analysis (applied social research methods). London: Sage Publications; 2001.

Gagnier JJ, Moher D, Boon H, Bombardier C, Beyene J. An empirical study using permutation-based resampling in meta-regression. Syst Rev. 2012;1(18):1–9.

Higgins J, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557.

Rosenberg MS. The file-drawer problem revisited: a general weighted method for calculating fail-safe numbers in meta-analysis. Evolution. 2005;59(2):464–8.

Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–63.

Adam PC, de Wit JB, Bourne CP, Knox D, Purchas J. Promoting regular testing: an examination of HIV and STI testing routines and associated socio-demographic, behavioral and social-cognitive factors among men who have sex with men in New South Wales, Australia. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):921–32.

Ratcliff TM, Zlotnick C, Cu-Uvin S, Payne N, Sly K, Flanigan T. Acceptance of HIV antibody testing among women in domestic violence shelters. J HIV/AIDS Soc Serv. 2012;11(3):291–304.

Andrinopoulos K, Kerrigan D, Figueroa JP, Reese R, Ellen JM. HIV coping self-efficacy: a key to understanding stigma and HIV test acceptance among incarcerated men in Jamaica. AIDS Care. 2010;22(3):339–47.

Berendes S, Rimal RN. Addressing the slow uptake of HIV testing in Malawi: the role of stigma, self-efficacy, and knowledge in the Malawi BRIDGE Project. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2011;22(3):215–28.

Berkley-Patton J, Moore EW, Hawes SM, Thompson CB, Bohn A. Factors related to HIV testing among an African American church-affiliated population. AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24(2):148–62.

Corno L, de Walque D. Socioeconomic determinants of stigmatization and HIV testing in Lesotho. AIDS Care. 2013;25(Suppl 1):S108–13.

Creel AH, Rimal RN. Factors related to HIV-testing behavior and interest in testing in Namibia. AIDS Care. 2011;23(7):901–7.

Cremin I, Cauchemez S, Garnett GP, Gregson S. Patterns of uptake of HIV testing in sub-Saharan Africa in the pre-treatment era. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(8):e26–37.

Das A, Babu GR, Ghosh P, Mahapatra T, Malmgren R, Detels R. Epidemiologic correlates of willingness to be tested for HIV and prior testing among married men in India. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;24(12):957–68.

Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Lee IC, Copenhaver MM. Stereotypes about people living with HIV: implications for perceptions of HIV risk and testing frequency among at-risk populations. AIDS Educ Prev. 2012;24(6):574–81.

Flowers P, Knussen C, Li J, McDaid L. Has testing been normalized? An analysis of changes in barriers to HIV testing among men who have sex with men between 2000 and 2010 in Scotland, UK. HIV Med. 2013;14(2):92–8.

Ford CL, Wallace SP, Newman PA, Lee SJ, Cunningham WE. Belief in AIDS-related conspiracy theories and mistrust in the government: relationship with HIV testing among at-risk older adults. Gerontologist. 2013;53(6):973–84.

Gu J, Lau JT, Tsui H. Psychological factors in association with uptake of voluntary counselling and testing for HIV among men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. Public Health. 2011;125(5):275–82.

Hong Y, Zhang C, Li X, et al. HIV testing behaviors among female sex workers in Southwest China. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(1):44–52.

Hoyt MA, Rubin LR, Nemeroff CJ, Lee J, Huebner DM, Proeschold-Bell RJ. HIV/AIDS-related institutional mistrust among multiethnic men who have sex with men: effects on HIV testing and risk behaviors. Health Psychol. 2012;31(3):269–77.

Huang ZJ, He N, Nehl EJ, et al. Social network and other correlates of HIV testing: findings from male sex workers and other MSM in Shanghai. China. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(4):858–71.

Johnston L, O’Bra H, Chopra M, et al. The associations of voluntary counseling and testing acceptance and the perceived likelihood of being hiv-infected among men with multiple sex partners in a South African Township. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(4):922–31.

Kaufman MR, Rimal RN, Carrasco M, et al. Using social and behavior change communication to increase HIV testing and condom use: the Malawi BRIDGE Project. AIDS Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):46–9.

Knox J, Sandfort T, Yi H, Reddy V, Maimane S. Social vulnerability and HIV testing among South African men who have sex with men. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22(12):709–13.

Koku EF. Desire for, and uptake of HIV tests by Ghanaian women: the relevance of community level stigma. J Community Health. 2011;36(2):289–99.

Lofquist DA. HIV testing behaviors of at-risk populations in Kenya. Bowling Green: Bowling Green State University; 2012.

Ma Q, Pan X, Cai G, Yan J, Ono-Kihara M, Kihara M. HIV antibody testing and its correlates among heterosexual attendees of sexually transmitted disease clinics in China. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):44.

Massari V, Lapostolle A, Cadot E, Parizot I, Dray-Spira R, Chauvin P. Gender, socio-economic status, migration origin and neighbourhood of residence are barriers to HIV testing in the Paris metropolitan area. AIDS Care. 2011;23(12):1609–18.

Matovu JKB, Kabanda J, Bwanika JB, et al. Determinants of HIV counseling and testing uptake among individuals in long-term sexual relationships in Uganda. Curr HIV Res. 2014;12(1):65–73.

McGarrity LA, Huebner DM. Behavioral intentions to HIV test and subsequent testing: the moderating role of sociodemographic characteristics. Health Psychol. 2014;33(4):396–400.

Melo APS, Machado CJ, Guimaraes MDC. HIV testing in psychiatric patients in Brazil. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(Suppl 3):S157–63.

Menser ME. Perceived risk, decsional balance, and HIV testing practices in college students. Pittsburgh: Univeristy of Pittsburgh; 2010.

Mirkuzie AH, Sisay MM, Moland KM, Astrom AN. Applying the theory of planned behaviour to explain HIV testing in antenatal settings in Addis Ababa—a cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:196.

Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Suchindran S, Delany-Moretlwe S. Factors associated with HIV testing among public sector clinic attendees in Johannesburg, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(4):913–21.

Prati G, Breveglieri M, Lelleri R, Furegato M, Gios L, Pietrantoni L. Psychosocial correlates of HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Italy: a cross-sectional study. Int J STD AIDS. 2013:0956462413515193.

Sabato TM, Burnett AJ, Kerr DL, Wagner L. Examining behavioral and psychosocial predictors of antibody testing among college youth: implications for HIV prevention education and testing. Am J Sex Educ. 2013;8(1–2):56–72.

Sambisa W, Curtis S, Mishra V. AIDS stigma as an obstacle to uptake of HIV testing: evidence from a Zimbabwean national population-based survey. AIDS Care. 2010;22(2):170–86.

Song Y, Li X, Zhang L, et al. HIV-testing behavior among young migrant men who have sex with men (MSM) in Beijing, China. AIDS Care. 2011;23(2):179–86.

Tun W, Kellerman S, Maimane S, et al. HIV-related conspiracy beliefs and its relationships with HIV testing and unprotected sex among men who have sex with men in Tshwane (Pretoria), South Africa. AIDS Care. 2012;24(4):459–67.

Wang B, Li X, Stanton B, McGuire J. Correlates of HIV/STD testing and willingness to test among rural-to-urban migrants in China. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(4):891–903.

Wilkerson JM, Fuchs EL, Brady SS, Jones-Webb R, Rosser BS. Correlates of human immunodeficiency virus/sexually transmitted infection (HIV/STI) testing and disclosure among HIV-negative collegiate men who have sex with men. J Am Coll Health. 2014;62(7):450–60.

Bogart LM, Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC. Endorsement of a genocidal HIV conspiracy as a barrier to HIV testing in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(1):115–6.

Bohnert AS, Latkin CA. HIV testing and conspiracy beliefs regarding the origins of HIV among African Americans. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(9):759–63.

Burchell AN, Calzavara LM, Myers T, et al. Voluntary HIV testing among inmates: sociodemographic, behavioral risk, and attitudinal correlates. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;32(5):534–41.

Delva W, Wuillaume F, Vansteelandt S, et al. HIV testing and sexually transmitted infection care among sexually active youth in the Balkans. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(10):817–21.

Desai MM, Rosenheck RA. HIV testing and receipt of test results among homeless persons with serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2287–94.

Fenton KA, Chinouya M, Davidson O, Copas A, Team Ms. HIV testing and high risk sexual behaviour among London’s migrant African communities: a participatory research study. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78(4):241–5.

Ford CL, Daniel M, Miller WC. High rates of HIV testing despite low perceived HIV risk among African-American sexually transmitted disease patients. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(6):841–4.

Ford CL, Daniel M, Earp JA, Kaufman JS, Golin CE, Miller WC. Perceived everyday racism, residential segregation, and HIV testing among patients at a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 1):S137–43.

Hendriksen ES, Hlubinka D, Chariyalertsak S, et al. Keep talking about it: HIV/AIDS-related communication and prior HIV testing in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Thailand. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1213–21.

Kakoko DC, Lugoe WL, Lie GT. Voluntary testing for HIV among a sample of Tanzanian teachers: a search for socio-demographic and socio-psychological correlates. AIDS Care. 2006;18(6):554–60.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC. HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counselling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(6):442–7.

Kellerman SE, Lehman JS, Lansky A, et al. HIV testing within at-risk populations in the United States and the reasons for seeking or avoiding HIV testing. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(2):202–10.

Lau JT, Wong WS. HIV antibody testing among the Hong Kong mainland Chinese cross-border sex networking population in Hong Kong. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(9):595–601.

Maguen S, Armistead LP, Kalichman S. Predictors of HIV antibody testing among Gay, Lesbian, and bisexual youth. J Adolesc Health. 2000;26(4):252–7.

McNaghten AD, Herold JM, Dube HM, St Louis ME. Response rates for providing a blood specimen for HIV testing in a population-based survey of young adults in Zimbabwe. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:145.

Norman LR. HIV testing practices in Jamaica. HIV Med. 2006;7(4):231–42.

Norman LR, Abreu S, Candelaria E, Sala A. HIV testing practices among women living in public housing in Puerto Rico. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(4):641–55.

Stein JA, Nyamathi A. Gender differences in behavioural and psychosocial predictors of HIV testing and return for test results in a high-risk population. AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):343–56.

Thierman S, Chi BH, Levy JW, Sinkala M, Goldenberg RL, Stringer JS. Individual-level predictors for HIV testing among antenatal attendees in Lusaka, Zambia. Am J Med Sci. 2006;332(1):13–7.

Thomas PE, Voetsch AC, Song B, et al. HIV risk behaviors and testing history in historically black college and university settings. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):115–25.

Wagner AC, Hart TA, Ghai A, Roberts KE. Sexual activity, social anxiety and fear of being judged negatively and HIV testing status in young adults. In: International AIDS Conference. Mexico City, 2008.

Yi S, Poudel KC, Yasuoka J, Ichikawa M, Tan V, Jimba M. Influencing factors for seeking HIV voluntary counseling and testing among tuberculosis patients in Cambodia. AIDS Care. 2009;21(4):529–34.

Norman LR, Gebre Y. Prevalence and correlates of HIV testing: an analysis of university students in Jamaica. MedGenMed. 2005;7(1):70.

MacPhail C, Pettifor A, Moyo W, Rees H. Factors associated with HIV testing among sexually active South African youth aged 15-24 years. AIDS Care. 2009;21(4):456–67.

Mack KA, Bland SD. HIV testing behaviors and attitudes regarding HIV/AIDS of adults aged 50-64. Gerontologist. 1999;39(6):687–94.

Dorr N, Krueckeberg S, Strathman A, Wood MD. Psychosocial correlates of voluntary HIV antibody testing in college students. AIDS Educ Prev. 1999;11(1):14–27.

Melo APS, César CC, de Assis Acurcio F, et al. Individual and treatment setting predictors of HIV/AIDS knowledge among psychiatric patients and their implications in a national multisite study in Brazil. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46(5):505–16.

Li X, Ning C, He X, et al. Near full-length genome sequence of a novel HIV type 1 second-generation recombinant form (CRF01_AE/CRF07_BC) identified among men who have sex with men in Jilin, China. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(12):1604–8.

Fagard R, Staessen J, Thijs L. Ambulatory blood pressure during antihypertensive therapy guided by conventional pressure. Blood Press Monit. 1996;1(3):279–81.

Woodward A, Howard N, Kollie S, Souare Y, von Roenne A, Borchert M. HIV knowledge, risk perception and avoidant behaviour change among Sierra Leonean refugees in Guinea. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(11):817–26.

Menser M. Perceived risk, decisional balance, and HIV testing practices in college students. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh; 2010.

Prati G, Breveglieri M, Lelleri R, Furegato M, Gios L, Pietrantoni L. Psychosocial correlates of HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Italy: a cross-sectional study. Int J STD AIDS. 2013;25(7):496–503.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Waltham: Academic press; 2013.

Norman LR, Gebre Y. Prevalence and correlates of HIV testing: an analysis of university students in Jamaica. J Int AIDS Soc. 2005;7(1):70.

Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1160–77.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychol Health. 2011;26(9):1113–27.

Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol Health. 1998;13(4):623–49.

Rosenst IM. Health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Quart. 1974;2(4):354–86.

Weinstein ND. The precaution adoption process. Health Psychol. 1988;7(4):355–86.

Leventhal H, Meyer D, Nerenz D. The common sense representation of illness danger. In: Rachman S, editor. Contributions to medical psychology. Oxford: Pergamon; 1980. p. 7–30.

Rogers RW. Attitude change and information integration in fear appeals. Psychol Rep. 1985;56:179–82.

Tversky A, Kahneman D. The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science. 1981;211(4481):453–8.

Rogers RW, Prentice-Dunn S. Protection motivation theory. In: Gochman DS, editor. Handbook of health behavior research 1: personal and social determinants. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. p. 113–32.

Catania JA, Coates TJ, Kegeles S. A test of the AIDS risk reduction model: psychosocial correlates of condom use in the AMEN cohort survey. Health Psychol. 1994;13(6):548–55.

Viechtbauer W, Lopez-Lopez JA, Sanchez-Meca J, Marin-Martinez F. A Comparison of procedures to test for moderators in mixed-effects meta-regression models. Psychol Methods. 2014.

Hempel S, Miles JN, Booth MJ, Wang Z, Morton SC, Shekelle PG. Risk of bias: a simulation study of power to detect study-level moderator effects in meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2013;2:107.

Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Performance of the trim and fill method in the presence of publication bias and between-study heterogeneity. Stat Med. 2007;26(25):4544–62.

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37.

Kaufman MR, Rimal RN, Carrasco M, et al. Using social and behavior change communication to increase HIV testing and condom use: the Malawi BRIDGE Project. AIDS Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):S46–9.

Boshamer CB, Bruce KE. A scale to measure attitudes about HIV-antibody testing: development and psychometric validation. AIDS Educ Prev. 1999;11(5):400–13.

Hou SI. Extending the use of the Web-based HIV Testing Belief Inventory to students attending historically Black colleges and universities: an examination of reliability and validity. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(1):80–90.

Khumalo-Sakutukwa G, Morin SF, Fritz K, et al. Project Accept (HPTN 043): a community-based intervention to reduce HIV incidence in populations at risk for HIV in sub-Saharan Africa and Thailand. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(4):422–31.

Alemagno SA, Stephens RC, Stephens P, Shaffer-King P, White P. Brief motivational intervention to reduce HIV risk and to increase HIV testing among offenders under community supervision. J Correct Health Care. 2009;15(3):210–21.

Foley K, Duran B, Morris P, et al. Using motivational interviewing to promote HIV testing at an American Indian substance abuse treatment facility. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2005;37(3):321–9.

Van Rompay KKA, Madhivanan P, Rafiq M, Krupp K, Chakrapani V, Selvam D. Empowering the people: development of an HIV peer education model for low literacy rural communities in India. Hum Resour Health. 2008;6:6.

Vidanapathirana J, Abramson MJ, Forbes A, Fairley C. Mass media interventions for promoting HIV testing: Cochrane systematic review. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(2):233–4.

Futterman DC, Peralta L, Rudy BJ, et al. The ACCESS (Adolescents Connected to Care, Evaluation, and Special Services) Project: social marketing to promote HIV testing to adolescents, methods and first year results from a six city campaign. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(3):19–29.

Wei C, Herrick A, Raymond HF, Anglemyer A, Gerbase A, Noar SM. Social marketing interventions to increase HIV/STI testing uptake among men who have sex with men and male-to-female transgender women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;9:CD009337.

Were W, Mermin J, Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, Kaharuza F. Home-based model for HIV voluntary counselling and testing. Lancet. 2003;361(9368):1569.

Pottie K, Medu O, Welch V, et al. Effect of rapid HIV testing on HIV incidence and services in populations at high risk for HIV exposure: an equity-focused systematic review. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006859.

Hensen B, Taoka S, Lewis JJ, Weiss HA, Hargreaves J. Systematic review of strategies to increase men’s HIV-testing in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2014;28(14):2133–45.

Kennedy CE, Fonner VA, Sweat MD, Okero FA, Baggaley R, O’Reilly KR. Provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1571–90.

Huba G, Melchior LA, De Veauuse NF, Hillary K, Singer B, Marconi K. A national program of innovative AIDS care projects and their evaluation. Home Health Care Serv Q. 1998;17(1):3–30.

Chesney MA, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Johnson LM, Folkman S. Coping effectiveness training for men living with HIV: results from a randomized clinical trial testing a group-based intervention. Psychosom Med. 2003;65(6):1038–46.

Fife BL. The role of constructed meaning in adaptation to the onset of life-threatening illness. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(10):2132–43.

Amon J, Brown T, Hogle J, et al. Guidelines for repeated behavioural surveys in populations at risk of HIV2000.

Project Accept Study Group N. Project Accept: a Phase III randomized control trial of community mobilization, mobile testing, same-day results, and post-test support for HIV in sub-Sahran Africa and Thailand. Stigma Pilot, May–June 2004.

Fortenberry JD, McFarlane M, Bleakley A, et al. Relationships of stigma and shame to gonorrhea and HIV screening. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(3):378–81.

Boshamer CB, Bruce KE. A scale to measure attitudes about HIV-antibody testing: development and psychometric validation. AIDS Educ Prev. 1999;11:400.

Huba G, Melchoir L. Module 64: Social Supports Form. Culver: The Measurement Group; 1996.

Study Group CaTE. Efficacy of voluntary HIV-1 counselling and testing in individuals and couples in Kenya, Tanzania, and Trinidad: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356(9224):103–12.

Carey MP, Morrison-Beedy D, Johnson BT. The HIV-Knowledge Questionnaire: development and evaluation of a reliable, valid, and practical self-administered questionnaire. AIDS Behav. 1997;1(1):61–74.

Gerkovich M, Williams K, Catley D, Goggin K. Development and validation of a scale to measure motivation to adhere to HIV medication. In: Poster session presented at: International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (IAPAC). 2008.

Carey MP, Schroder KE. Development and psychometric evaluation of the brief HIV Knowledge Questionnaire. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14(2):172.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Jooste S, et al. Development of a brief scale to measure AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2005;9(2):135–43.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401.

Strathman A, Gleicher F, Boninger DS, Edwards CS. The consideration of future consequences: weighing immediate and distant outcomes of behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;66(4):742.

Longshore D, Stein J, Anglin MD. Psychosocial antecedents of needle/syringe disinfection by drug users: a theory-based prospective analysis. AIDS Educ Prev. 1997;9(5):442–59.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS among African Americans. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005.

McNeilly MD, Anderson NB, Robinson EL, et al. Convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity of the Perceived Racism Scale: a multidimensional assessment of the experience of racism among African Americans. Handb Tests Meas Black Popul. 1996;2:359–73.

Vines AI, McNeilly MD, Stevens J, Hertz-Picciotto I, Bohlig M, Baird DD. Development and reliability of a Telephone-Administered Perceived Racism Scale (TPRS): a tool for epidemiological use. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(2):251.

Bogart LM, Wagner G, Galvan FH, Banks D. Conspiracy beliefs about HIV are related to antiretroviral treatment nonadherence among African American men with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2010;53(5):648.

(ANES) TANES. The ANES guide to public opinion and electoral behavior. 2011. http://www.electionstudies.org/studypages/cdf/anes_cdf_int.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2014.

DeHart DD, Birkimer JC. Trying to practice safer sex: development of the sexual risks scale. J Sex Res. 1997;34(1):11–25.

Genberg BL, Hlavka Z, Konda KA, et al. A comparison of HIV/AIDS-related stigma in four countries: negative attitudes and perceived acts of discrimination towards people living with HIV/AIDS. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(12):2279–87.

Aspinwall LG, Kemeny ME, Taylor SE, Schneider SG, Dudley JP. Psychosocial predictors of gay men’s AIDS risk-reduction behavior. Health Psychol. 1991;10(6):432.

Bryan AD, Aiken LS, West SG. Young women’s condom use: the influence of acceptance of sexuality, control over the sexual encounter, and perceived susceptibility to common STDs. Health Psychol. 1997;16(5):468.

Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Bushman BJ. Relation between perceived vulnerability to HIV and precautionary sexual behavior. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(3):390.

Hendrick S, Hendrick C. Multidimensionality of sexual attitudes. J Sex Res. 1987;23(4):502–26.

Zane N, Yeh M. The use of culturally-based variables in assessment: Studies on loss of face. Asian American mental health. New York: Springer; 2002. p. 123–38.

Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Muhammad A. Psychological predictors of risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among low-income inner-city men: a community-based survey. Psychol Health. 1997;12(4):493–503.

Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1991-1999. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(3):371–7.

Bryan AD, Fisher JD, Benziger TJ. Determinants of HIV risk among Indian truck drivers. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(11):1413–26.