Abstract

Food is becoming an increasingly important issue in the urban context. Urban food policies are a new phenomenon in Czechia, where urban food alternatives to the current food regime are promoted by food movements or take the form of traditional self-provisioning. This paper examines how urban food governance in Prague and Brno is constituted based on the municipalities’ relations with actors engaged in urban food alternatives. We argue that prioritizing aspects of local food system transformation compliant with the status quo is non-systemic and implies a fragmentation of urban food alternatives based on different levels of social capital and radicality. We conceptualize urban food alternatives as values-based modes of production and consumption and focus on values that guide urban food governance in its participatory and territorial interplay with the actors of urban food alternatives. Our analysis reveals that the values underpinning the two cities’ progressive food policies do not match reality on the ground. We propose four types of relations between the two examined cities and aspects of the local food system transformation. Aspects compliant with the status quo, such as food waste reduction and community gardening are embraced, whereas those requiring more public intervention, such as public procurement, short supply chains, or the protection of cultivable land are disregarded, degraded, or, at most, subject to experimentation as part of biodiversity protection. Chances for a successful transformation of the local food system under such governance are low but can be increased by strengthening social capital and coalition work among urban food alternatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Globalized industrial agri-food systems are widely recognized for their impact on health costs, environmental degradation, and national security threats, which are further aggravated at present by multifaceted socioeconomic and geopolitical crises posing new risks to food security and access to food (Morgan 2009, 2015). These threats have been analyzed globally from the perspective of the corporate food regime (McMichael 2009, 2012). While issues related to food availability have been traditionally recognized as a problem of the Global South and rural areas, cities in the Global North now increasingly deal with problems associated with food accessibility and affordability (Opitz et al. 2016; Sonnino 2019). By rescaling food policies, a growing number of urban governments now address this change in what is an interrelated and context-dependent food system with strategies that integrate health, environment, social justice, citizen participation, and community building (Mendes and Sonnino 2019).

In these developments, an important role is played by urban food movements, which can be characterized as a form of urban activism driven by a collective desire for food system transformation towards more local, sustainable, equitable, democratic, and empowering modes of food production and consumption (Manganelli 2022). In our paper, we refer to these as urban food alternatives so as to include alternatives with a non-activist character. We analyze them through an interdisciplinary framework of values-based modes of production and consumption, encompassing both alternative food networks (AFNs), the food sovereignty movement, and more formal NGOs promoting systemic and institutional changes, as well as various forms of urban agriculture and food self-provisioning (Pixová and Plank 2022; Plank et al. 2020). The roles these food alternatives play largely depend on the approach of municipal governments to food policy activity and their links to independent organizations (MacRae and Donahue 2013). In this regard, social capital between actors also plays an important role within local food systems (Bauermeister 2016; Glowacki-Dudka et al. 2013; Levkoe 2014; Nosratabadi et al. 2020),

Urban food governance and urban food movements are relatively unexplored in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), where food systems often retain some of their pre-capitalist or pre-industrial legacies, such as high levels of food self-provisioning (see Jehlička et al. 2020; Pungas 2023). At the same time, these societies are exposed to a particularly strong version of neoliberalism, manifested, for example, in extremely efficient cuts in social expenditures (Chelcea and Druţǎ 2016) and frequent conflicts between the principles of the capitalist urban economy and socialist urban features (Sýkora and Bouzarovski 2012). Although there is a relatively rich body of research on CEE food systems and food alternatives (e.g., Jehlička et al. 2020; Daněk et al. 2022; Moudrý et al. 2018; Pungas 2019; Zagata 2010, 2012, 2019), some of which focus on their urban settings (see e.g. Boukharaeva and Marloie 2015; Gibas and Boumová 2020; Spilková et al. 2013; Spilková and Vágner 2012; Trendov 2018) or their (lack of) framing as an activist practice (Sovová and Veen 2020; Pungas 2023), food from the perspective of urban governance and social movements remains under-researched.

Urban food policies introduced in the most recent strategic and climate plans of Prague and Brno, Czechia’s capital and second largest city respectively, suggest that food is appearing on the radar of some cities in the CEE region. However, given the policies’ novelty (Pixová and Plank 2022), local contextual factors, frequent cases of non-transparent abuse of political power, and a large gap between public administration and citizens in Czech cities (Pixová 2018, 2020), it is questionable how urban food policies translate into urban food governance and to what ends such governance serves.

In the following article, we therefore pose the following overall research questions: What are the characteristics of urban food governance in Prague and Brno, and what is its potential to lead to a successful transformation of the local food system? Further questions are as follows: (i) What policies, based on what kind of values, support urban food agendas in Prague and Brno? (ii) How is the two cities’ urban food governance constituted based on the municipal actors’ and institutions’ relations to different aspects of the local food system transformation and the social capital of different actors involved in urban food alternatives? Finally, (iii) what gaps in the local food system transformation can be identified by comparing these relations to the role of different aspects in the corporate food regime and the capitalist urban economy? We argue that urban food governance, which prioritizes only environmental aspects of food and neglects socioeconomic issues, such as food (in)security or food self-provisioning, is non-systemic. Instead of recognizing local needs, it relates to urban food alternatives based on their different linking social capital and compliance with the corporate food regime and capitalist urban economy.

The article is structured as follows: In the coming section, we explain our theoretical framework, where we combine insights gleaned from urban food alternatives through the lens of urban food governance, territoriality, and social capital. We next present our methods, which consist of document analyses and qualitative interviews. In the ensuing section, we examine the urban food policies in Prague and Brno. The next section examines how the cities relate to different aspects of the local food system transformation and urban food alternatives with varying levels of social capital. Before concluding, we discuss these relations in connection to the compatibility of different aspects of local food system transformation with the corporate food regime and capitalist urban economy. Finally, we identify gaps in urban food governance and local food system transformation and suggest ways of narrowing them.

Urban food alternatives

Our focus here is on urban food alternatives within the corporate food regime (McMichael 2009, 2012; Plank et al. 2020), which we analyze through an interdisciplinary theoretical framework of values-based modes of production and consumption, concentrating on actors and institutions, values, and their multiscalar interplay (Brunner 2022; Pixová and Plank 2022). Given the urban context, we discuss urban food alternatives in connection to urban food governance, territoriality, and the role of social capital in local food system transformation.

Urban food governance and the territoriality of urban food alternatives

Urban food policies have recently gained recognition for their transformative potential in dealing with the systemic and evolutionary crisis in the global food system, which cannot be adequately addressed by market and production-oriented solutions employed within dominant governance approaches. Rescaling the politics of food, particularly in the cities of the Global North, has therefore emerged as a response to the urgent need for integrated food security policies that would ensure access to food while engendering a sustainable transformation (Coulson and Sonnino 2019; Sonnino 2019). As shown by Mendes and Sonnino (2019), urban food strategies in the cities of the Global North differ considerably in terms of format and composition but are characterized by a list of common values that include a systemic approach, relocalization, translocalism, and participatory governance (Mendes and Sonnino 2019; Sonnino 2019).

As a consequence of these developments, there has been an increasing awareness of “the significance of bringing together a range of individuals, groups, and organizations that encompass a desire to move towards more sustainable food systems” and to “enact more emancipatory food politics” (Coulson and Sonnino 2019, p. 178). An irreplaceable role in this regard is played by urban food movements, which comprise a wide range of actors, groups, initiatives, and organizations engaged in practicing and promoting various local alternatives, such as urban agriculture; urban gardening; solidarity-based business models, such as community-supported agriculture (CSA), food coops and other types of AFNs; initiatives promoting and working towards food sovereignty; NGOs engaging in political advocacy; networks focused on connecting producers and consumers and generating broader support for a food system transition; and many others (Clendenning et al. 2016; Lyons et al. 2013; Manganelli 2022). In some cities, urban food movements belong to a wide collection of stakeholders involved in various alternative approaches to urban food governance (Haysom 2015; Morgan 2015), sometimes also referred to as pluralistic governance (Koc and Bas 2012 in Haysom 2015). Food movements and government involvement/cooperation in this case may include municipally driven food policy or one driven by independent organizations as well as various forms of hybrid governance involving civil society organizations and governments (MacRae and Donahue 2013).

The process of engendering a food system transformation via multistakeholder urban governance is nonetheless neither smooth nor uncontested. The lens of critical geography and political ecology applied by Coulson and Sonnino (2019) reveals that multidimensional constraints arise from complex institutional landscapes; the unstable, contested, and relational character of multiscalar governance; and unequal access to power and resources among stakeholders. Particular actors, interventions, and trajectories may be prioritized over others or be at risk of co-option by neoliberal processes of ecological modernization for the sake of interurban competition. Conversely, other actors, priorities, alternative knowledge, and imaginaries that may inform food policy development in a way that effectively addresses the negative externalities of the capitalist food system may be silenced or marginalized (Coulson and Sonnino 2019; see also Jessop 2010 on strategic selectivities). Notably, this has often been the case for food self-provisioning in the post-socialist CEE context, which both international literature and official state documents have had a tendency to view as a coping strategy and demodernization (Jehlička et al. 2012; Jehlička and Smith 2011; Sovová and Veen 2020) despite its important contribution to sustainability (Smith and Jehlička 2013; Vávra et al. 2018), resilience (Jehlička et al. 2019; Pungas 2019), food sovereignty (Visser et al. 2015), and food democracy (Pungas 2023).

To make clear the gaps in, barriers to, and opportunities for successful and democratic urban governance of alternative food systems, Manganelli proposes a hybrid governance approach in order to explore urban food movements from the perspective of tensions and obstacles in critical governance experienced in their interactions with other actors, players, and interests in the city and in negotiating conditions and changes necessary for food system transformation (Manganelli 2020, 2022; Manganelli et al. 2020). One such tension arises from local alternatives’ access to land, which is at all scales under the pressure of capitalism (Araghi 1995; Plank et al. 2023) and its “regressive processes of territorial restructuring” (Alonso-Fradejas et al. 2015, p. 441). By controlling key institutions and social relations, capital can control territories suitable for accumulation, subjecting land to commodification and financialization, and undermining democratic land control and food sovereignty (Alonso-Fradejas et al. 2015, p. 441). In their search for cultivable land, food movements as well as non-activist food alternatives in urban areas are therefore confronted with “urban planning policy and state structures whose affinity with urban agriculture is on average quite low” (Manganelli et al. 2020, p. 299). Quality land in reasonable proximity to urban areas is scarce, conditioned by property and ownership structures and land-use rights, and limited due to the compliance of public administrations with the privatization pressures of various real-estate and rent-seeking interests in addition to the continued reluctance of local authorities to facilitate gardening and small-scale agriculture in public spaces (Manganelli et al. 2020).

In the current state of polycrisis, urban governments’ bias towards financialized land use increasingly interferes with calls for environmental governance and resilience processes. This includes the need to deal with previously overlooked agendas, such as urban food planning and governance (Morgan 2009, 2015; Opitz et al. 2016; Sonnino 2019) that is open to alternative urban food innovations (Haysom 2015) and cooperation with civil society organizations (Manganelli 2022; Mendes and Sonnino 2019). The mismatches and contradictions between these agendas and cities trapped in the current neoliberal form of crisis-contingent capitalism nonetheless often result in environmental governance being financialized too (Cousins and Hill 2021), producing incoherent and counterproductive policy results in terms of supporting sustainability or increasing food security. This is made evident by the exacerbation of inequalities through unjust greening outcomes and green gentrification (García-Lamarca et al. 2022) or by policy actors’ disregard for non-market household food production in post-socialist societies (Jehlička and Smith 2011). In other contexts, urban agriculture is enrolled as an instrument of urban greening and sustainability planning aimed at achieving economic competitiveness instead of dealing with food insecurity (McCann et al. 2022; Thornbush 2015; Walker 2016) or at widening the rent gap on vacant land until replacement by higher value development (McCann et al. 2022).

Given the pressures of neoliberal urbanization and financialization combined with compact urban environments, a local food system transformation cannot be limited to the territories demarcated by municipal administrative boundaries. Some cities are increasingly recognizing the necessity to tackle food security and food system relocalization in the context of regional food systems and to support regional food, for example, via public procurement or the establishment of market networks throughout the city that provide fresh seasonal food from local and regional producers (Sonnino 2019). Mobilizing such regional cooperation nonetheless goes hand in hand with other cultural values and principles, such as a commitment to a systemic approach that considers the multidimensionality of the food system and integration with other policies and sectors, recognition of cities’ impact on global food security, and the inclusion and cooperation of actors from different sectors to ensure the recognition of local needs and the long-term success of local food initiatives (Sonnino 2019).

Social capital analysis in urban food system transformation

A large body of research has shown that the success of social movements in affecting social change depends to a large extent on their social capital. These are major elements of their social relationships, such as “social networks, civic engagement, norms of reciprocity, and generalised trust” as well as “collective assets in the form of shared norms, values, beliefs, trust, networks, social relations, and institutions that facilitate cooperation and collective action for mutual benefits” (Bhandari and Yasunobu 2009, p. 480). Distinction can be made between bonding social capital—connections within a group or community with high levels of similarity—and bridging social capital—connections and associations across differences (Putnam 2000). Bridging social capital arising from vertical associations can be distinguished as linking social capital, which captures the power dynamics of actors’ connections to the political sphere or institutions (Woolcock 2001).

Different forms of social capital are also essential for actors striving for a local food system transformation. Strong social capital can, for example, improve the viability of partnerships within local food systems and local food movements (Glowacki-Dudka et al. 2013), directly and indirectly improve community food security (Nosratabadi et al. 2020), or be a decisive factor in the transformational potential of local alternatives (Plank et al. 2020). Glowacki-Dudka et al. (2013) have shown that connections and reciprocity built on trust and unified goals contribute to the expansion of social capital, whereas the opposite leads to its weakening. Tensions can be produced by different levels of social capital (Levkoe 2014) or its different forms (Bauermeister 2016). Strong bonding capital may, for instance, hinder a group’s willingness to cooperate with others, thus limiting its bridging social capital, that is, its access to new information, resources, opportunities, and strategies for collective action and the ability to achieve common goals (Bauermeister 2016).

Social capital resources can also be gained from being active in social movements (Tindall et al. 2012), for example, access to important information about relevant issues, linking social capital, and political influence. According to Tindall et al. (2012), contacts with “influential and powerful others” endow social movements and their members with social capital in the form of “social certification” and the opportunity to “speak legitimately on behalf of the movement” (Tindall et al. 2012, p. 8). Social capital overly concentrated in one group of actors can however also prevent social change, such as a sustainable food system transformation (Bauermeister 2016). Already existing social capital at the community level can also be destroyed by conflicting government policies and incentives (Dale and Newman 2010). For the success of an initiative’s network, it is crucial to “create bridging and vertical ties” (Dale and Newman 2010, p. 18) that also involve marginalized communities in order to enable their access to autonomy, empowerment, and external resources. These can enlarge their social safety net and their ability to help themselves through their own agency. The ability to successfully achieve social change through such ties, according to Levkoe (2014), depends on social capital, such as trust, clear common objectives, and mutual benefits, that partners can work towards and further strengthen through cooperation.

In the following analysis, we first analyze urban food policies in Prague and Brno according to the values and principles outlined by Sonnino (2019). Second, we present the municipal actors, institutions, and urban food alternatives relevant to the local food system transformation in the two cities, focusing primarily on municipal relations to different aspects of this transformation and social capital among actors engaged in urban food alternatives. Third, we focus on these relations in connection to the values of urban food governance outlined by Sonnino (2019) and compare them with the linking and bridging social capital of urban food alternatives and their role within the corporate food regime and the capitalist urban economy. We conclude by identifying some of the main gaps in urban food governance in Prague and Brno and suggest opportunities for instigating a more successful transformation of local food systems.

Methods

In exploring urban food policies in Prague and Brno, we first conducted desk research in summer 2022, shortly after urban food policies appeared for the first time in the two cities’ strategic socioeconomic development plans, climate plans, and other related materials published or adopted between 2016 and 2022 (see the following section for more detail) (Pixová and Plank 2022). In our analysis of these documents, we focused on identifying aspects of local food system transformation that these policies support as well as those that are omitted. We analyzed them from the perspective of the values that inform the progressive food policy landscapes of cities in the Global North according to Sonnino (2019). The results, presented in detail below, assessed (1) a systemic approach based on the policies’ recognition of the multidimensionality and multiscalarity of food systems and associated problems of both a social and an environmental nature; (2) relocalization by identifying the food policies’ emphasis on local food, short supply chains, circularity, and development of local economies; (3) translocalism with respect to the two cities’ ambition to become part of translocal networks committed to a local food system transformation; and (4) participatory food governance by searching for suggestions of specific procedures and tools, such as a food council and participatory forms of food governance that acknowledge all actors relevant to a local food system transformation. This value was further explored by qualitative interviewing.

Our second step involved conducting 32 qualitative semi-structured interviews with 39 people (see Table 1) that explored the linking and bridging social capital of actors engaged in local food system transformation by focusing on their mutual relations and forms of cooperation. We selected our interview partners by identifying the authors of the urban food policies and actors whose role in food system transformation appeared in the analyzed documents and continually updated them by snowballing. In this way we identified other relevant municipal actors and institutions as well as nongovernmental and grassroots actors engaged in various aspects of local food system transformation and food governance. Of the 32 interviews, 3 involved two interviewees, and 2 involved three interviewees. We conducted 20 interviews in Prague and 12 in Brno. Actors in Prague were, with two exceptions, all interviewed in person, while six interviews in Brno were held online. In addition to formal interviews, we also conducted numerous informal interviews with urban activists, gardeners, CSA members, ecological farmers, and municipal politicians. For anonymization purposes, the cities of the interview subjects are not indicated in Table 1.

Based on the received data, we distinguish between the following urban food alternatives: (a) NGOs focused on waste reduction, (b) community gardening, (c) urban organic farmers, (d) food initiatives promoting short food supply chains, (e) NGOs promoting public procurement, (f) farmers’ markets, and (g) allotment gardening. The interviews also allowed us to identify aspects of local food system transformation that are missing in the two cities’ food policies despite their relevance to urban food alternatives. In the following section, we introduce both supported and omitted aspects of local food system transformation and suggest that the municipalities relate to them in four different ways that are dependent upon their compatibility with the corporate food regime and the capitalist urban economy as well as on different levels of social capital of relevant urban food alternatives.

Urban food policies in Prague and Brno

Urban food policies are spelled out to a different extent in the respective Prague and Brno documents. Prague’s strategic plan (Prague Institute of Planning and Development 2016), which formulates a common vision of Prague’s socioeconomic development, broadly sets out to support the city’s food self-sufficiency, urban agriculture and gardening, alternative food networks, and cooperation with stakeholders in agriculture. Smart Prague Conception 2030 (Deloitte 2017), which outlines the implementation of technological innovations, features fuzzy criticism of Prague’s dependence on food from the countryside (Pixová and Plank 2022). Our analysis thus primarily draws on Circular Prague 2030 (Magistrate of the Capital City of Prague 2022), a supplementary document of Prague’s Climate Plan (Magistrate of the Capital City of Prague 2021) that contains a whole chapter focused on food and agriculture. In Brno, we mainly draw on the Strategy #brno2050 documents (Magistrate of the City of Brno 2017), which is Brno’s socioeconomic strategy. Unlike in Prague, this strategy also contains Brno’s climate plan, in which urban food policies are integrated in a comparatively less elaborate way in the chapters focused on nature, circularity, and self-sufficiency. We also draw on the two cities’ climate change adaptation strategies (Magistrate of the Capital City of Prague 2017; Magistrate of the City of Brno 2016), which declare support for urban agriculture and gardening.

Drawing on the values—systemic approach, relocalization, translocalism, and participatory food governance—that inform progressive food policy landscapes of the cities in the Global North in accordance with Sonnino (2019), we identified to what extent these can also be found in the urban food policies of Prague and Brno.

Neither Prague’s nor Brno’s urban food policies fully employ a systemic approach, as they do not pay equal attention to all aspects, stages, and scales of food systems. Circular Prague 2030 and Strategy #brno2050 accentuate the circular economy, that is, using short supply chains, lowering food’s ecological footprint, and reducing and reusing food waste. The two cities’ climate change adaptation strategies see organic agriculture and urban gardening as a tool for increasing biodiversity, water retention, and soil care and lowering erosion and the heat island effect. While Prague’s strategic plan (Prague Institute of Planning and Development 2016) mentions the need to preserve the tradition of allotment gardening, Circular Prague 2030 and Strategy #brno2050 focus mainly on community gardens, associating them with local food, health, nutrition, well-being, community building, and social inclusion. Circular Prague 2030 mentions employment and integration of socially disadvantaged groups in city farms and community gardens as well as charitable donations of cooked meals as a measure supporting food waste reduction. Food insecurity is not mentioned.

Relocalization is embraced in both cities’ urban food policies although the concept is overly focused on urban agriculture, whereas regional and peri-urban agriculture are only vaguely mentioned. Circular Prague 2030 suggests supporting local organic food by public procurement in school canteens, building storage spaces for farmers, and establishing a city farm as well as an online platform for connecting farmers with consumers. It mentions the existence of farmers’ markets, CSAs, and food cooperatives as proof of the popularity of local organic food and suggests updating the currently outdated general plan of allotment gardens to include new trends in urban agriculture (aquaponic, rooftop, etc.).

Translocalism is a missing value in Prague’s and Brno’s urban food policies. Circular Prague 2030 mentions the EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy, Brussel’s Good Food Strategy, and the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact (Milan Urban Food Policy Pact n.d.) as a source of inspiration but without the ambition to become part of translocal networks.

In both documents, participatory food governance is defined in a separate chapter without a specific connection to food and agriculture or concrete measures. Circular Prague 2030 only suggests establishing a coordinator for community gardens and for a circular economy. The question of participatory governance will be further elaborated below, where we explore the two municipalities’ relations to different aspects of local food system transformation, and the different social capital of relevant urban food alternatives.

Four types of municipal relations to different aspects of local food system transformation

In the following, we analyze how urban food governance in Prague and Brno is constituted by introducing the different municipal actors and institutions engaged in it, and their relations to the different aspects of local food system transformation and relevant urban food alternatives. Based on the document analysis, we identified aspects of local food system transformation which are included in urban food policies, such as the reduction and reuse of food waste and new trends in urban agriculture, for example, community gardens, biodiversity protection via ecological farming, short food supply chains, and public procurement. Based on the qualitative interviews, we identified further missing aspects despite their relevance to urban food alternatives and local food system transformation, for instance, sustenance of local and regional smallholder farmers’ livelihoods, food (in)security, food self-provisioning, and the protection of cultivable land from further urbanization. Altogether, we propose four types of relations between municipalities and different aspects of local food system transformation: (i) embracement, (ii) experimentation, (iii) disregard, and (iv) degradation. We discuss these relations in their interplay with different linking and bridging social capital among actors in urban food alternatives.

Since publishing urban food policies, neither Prague nor Brno have established a position for an official responsible person or a contact point for the cities’ food system transformation. Our interviews revealed that the responsibility is fragmented across different municipal institutions and departments. In Prague, the urban food policies were drafted by the Prague Innovation Institute, which is a municipally funded public benefit organization. In Brno, they are part of a strategic plan administered by Brno’s department of strategic planning. In both cities, the food agenda is mainly managed by environmental protection departments, which in Prague, also cooperates with the Office of Landscape and Green Infrastructure at Prague Institute of Planning and Development. Brno also has an agricultural department, which deals with administrative and technical issues. In both cities, urban agriculture and farmers’ markets are also managed by property departments and subcontractors. Food is not on the agenda of the two cities’ social departments.

During our research between 2022 and 2023, municipal elections in October 2023 led to a change in the political leadership of both cities. Prague’s Climate Plan (Magistrate of the Capital City of Prague 2021) and its supplementary documents, including urban food policies, were adopted during the 2018–2022 electoral term under the governing coalition of two liberal parties, the Pirate Party and the Mayors and Independents (STAN), and a citizens’ association Praha sobě. After the elections, a coalition of right-wing conservative parties named SPOLU formed a governing coalition with the liberal parties from the previous leadership, without Praha sobě. The mayoral post was taken by the Civic Democratic Party, which has criticized Prague’s Climate Plan for being “activist” and “unrealistic” (Občanská demokratická strana 2021). Brno’s strategic documents were prepared during the 2014–2018 electoral term in cooperation with external experts, some of which were recommended by the city’s two progressive councilors from the Green Party and the political movement Žít Brno. These political subjects have had no representation in Brno’s council since 2018.

Embracement of reduction and reuse of food waste and new trends in urban agriculture

The first identified relation between the two cities and different aspects of local food system transformation is embracement and concerns issues surrounding circularity, such as the reuse and reduction of food waste (e.g., via composting and biofuel stations) and community gardens, which receive the most attention in Circular Prague 2030 and Strategy #brno2050. According to one municipal actor, food waste, which was neglected for decades, is the most pressing food issue and must be now prioritized (ID# 26).

Kokoza, an NGO that operates as a networker and promoter of community gardening and composting initiatives across Czechia, and Zachraň jídlo, an NGO promoting food waste reduction, were both consulted on Circular Prague 2030. Kokoza introduced the first community garden in Prague in 2012 and nowadays engages in advocacy, education, and awareness raising and establishes new community gardens for various clients, including developers, corporations, and supermarkets. It is well-networked with both national and municipal government institutions as well as nongovernmental actors. The NGO has links to the Ministry of the Environment and various municipal institutions. Its objective is to incorporate community gardening into legislative frameworks, urban plans, and policies. The goal is that growing plants and composting become a commonplace, institutionally supported urban activity (ID# 17).

In February 2024, Kokoza monitored 150 community gardens in Czechia, with 69 in Prague and 14 in Brno. Most are small and focused on socializing and leisure (Dubová et al. 2020; Spilková 2017). Only four community gardens in or near Prague (Kuchyňka, Metrofarm, MetroPole and KomPot) are production oriented. This still rather limited potential to grow substantial amounts of local food is disproportionate to the large attention community gardens receive from municipalities. Attesting to its strong linking social capital, Kokoza, in cooperation with Prague, issued a community gardening methodology (Pokorná 2020), and several districts have designated community gardening coordinators. At the time of our research, Brno’s department of environmental protection was mapping ways of supporting community gardens in the city (ID# 19).

Interviewed municipal actors saw community gardens as innovative and inclusive (ID# 5, 19, 22), but community gardeners mentioned their short-term leases and top-down expectations of flexible adaptability to urban development (ID# 3, 18, 28). Our interviews showed that unlike allotment gardeners, community gardeners are comparatively younger; more frequently use the sustainability discourse; network with other actors involved in urban food alternatives, including some of the ecological farms in urban and peri-urban areas; or even operate CSA initiatives (ID# 4, 9, 17, 18, 24, 28). Strong bridging social capital within these networks allows them to share experience, occasionally collaborate, or participate in public debates. However, they lack an umbrella organization with formal membership, complicating community gardeners’ ability to act collectively.

Zachraň jídlo, the second NGO that consulted on Prague’s urban food policies, has a goal to reduce food waste in Czechia by 50%. Their campaigns focus on awareness raising, harvest gleaning, food donations, or advocacy in policymaking and in businesses, including retail chains. It has links to both national and municipal government institutions. The Ministry of the Environment and the Prague municipality fund its activities related to circularity (Zachraň jídlo n.d.). Partnering with several public, private, and nongovernmental organizations, including NGOs concerned with environment and climate protection, Zachraň jídlo has strong linking and bridging social capital, but its narrow focus on food waste limits closer cooperation with other food alternatives (ID# 2).

In Brno, urban food policies were drafted in cooperation with the Institute of Circular Economy (INCIEN), the main Czech NGO raising awareness about the unsustainability and overexploitation of a linear economy. INCIEN operates as a think tank, consulting with municipalities and engaging in advocacy at the national level. Its cooperation with a wide range of companies; governmental, nongovernmental, and industry organizations; educational and research institutions; and individuals interested in circularity (INCIEN n.d.) has provided it with extremely strong linking and bridging social capital.

Experimentation with biodiversity protection through ecological farming

The second way in which the municipalities relate to the local food system transformation is experimentation with biodiversity protection through the help of ecological farming. While the positive environmental effects of ecological urban agriculture and gardening are emphasized in both cities’ climate change adaptation strategies, we identified municipal experiments with ecological farming only in Prague.

In Prague, organic urban farming was set in motion by several biologists from the municipal department of environmental protection (ID# 8). These biologists have had a good experience supporting biodiversity via the management of Prague’s numerous orchards. In the second half of the 2010s, they also experimented with vegetable growing on municipal fields in the Prague 14 district but stopped because people were stealing the produce. The biologists later proposed a pilot project experimenting with leasing 398 hectares of municipal farmland to organic farmers instead of conventional farmers. The project received political support in 2019 from Prague’s incumbent vice-mayor, Petr Hlubuček from STAN, the main political leader of Prague’s climate plan—in 2022, he was however accused of corruption at the Prague Public Transit Company (Radio Prague International 2022 Jun 16). Selected farmers, including production-oriented community gardens, such as Metrofarm, were able to start farming before that, in 2021 (ID# 8), but an informally interviewed organic farmer revealed that in autumn 2023, some of the new farmers still did not have official contracts with the city.

New organic farmers receive small municipal grants for their activities on municipal fields, but their links to municipalities are weak and limited to informal contacts with the biologists from the department of environmental protection, who occasionally pay them informal visits out of personal interest in ensuring that appropriate farming practices with a positive effect on biodiversity are applied (ID# 7, 8, 18). From an informally interviewed organic farmer, we learned that not all new farmers on municipal fields however use ecological farming practices.

As regards the bridging social capital of urban organic farmers, there are differences that depend on the character of each farm and the amount and type of its production. Some of the larger and more established farms use municipal fields in addition to those outside of the municipality’s authority, and their size of production allows them to operate within the conventional food system. Others, such as Prokopská farma, cooperate with various food initiatives. We also interviewed a farmer (ID# 7) who was not networked with other urban food alternatives and had only a few loose contacts with other farmers. This farmer was struggling with the workload and lacked suitable coworkers, machinery, or a stable outlet for his produce. As we discuss below, Prague’s experimentation with urban ecological farming to enhance biodiversity fails to account for the socioeconomic side of food production among local smallholders and disregards aspects of the local food system transformation aimed at shortening supply chains between farmers and consumers. Moreover, we learned about municipal plans for future real estate development on some of the municipal fields where biodiversity is currently being laboriously restored (ID# 7).

Disregard for smallholders’ livelihoods, short food supply chains, public procurement, and food security

The third relation between municipalities and aspects of local food system transformation can be characterized as disregard, which primarily concerns citizens’ access to local organic food and the livelihoods of smallholder farmers. Interviews with municipal actors (ID# 8), representatives of farmers and production-oriented community gardens (ID# 7, 18), and food initiatives (ID# 1, 20, 23, 24) showed that further support aimed at increasing local organic production and consumption outlined in Circular Prague 2030, such as building storage spaces, creating a digital platform for connecting farmers with consumers, or supporting urban and regional farms through public procurement has not been provided. In this regard, the municipal biologists who monitor ecological farming practices on municipal fields rely on supply and demand to disburse the more expensive organic food: “I think it worked out here because of the local purchasing power to buy organic agricultural products in comparison to other parts of Czechia. When you offer organic pumpkins and zucchini here, they disappear in a flash. The buyers are willing to pay higher prices” (ID# 8).

A relatively widespread outlet for local organic food is farmers’ markets, mentioned in Circular Prague 2030 to demonstrate the popularity of local fresh food. Municipalities in the two cities however do not provide farmers’ markets with stable support beyond leasing space and granting permits. According to an interviewed organizer of farmers’ markets, neither national nor municipal government institutions take farmers’ markets seriously and see them only as a novelty or form of entertainment (ID# 29). The lack of institutional support is exemplified by the state-mandated closures of the markets during the COVID-19 pandemic between 2020 and 2021, despite retail chains staying open (iDNES 2021 April 10). Moreover, municipalities do not differentiate between markets based on their adherence to the code of the Association of Farmers’ Markets (Asociace farmářských tržišť n.d.), which ensures authenticity and localness in the markets and whose members represent only about 7% of Czech farmers’ market organizers (ID# 29). In autumn 2023, farmers struggled against the decision of a company administering Prague’s waterfront to replace their market with a Christmas market and complained about the lack of clarity regarding municipal plans to keep their market (PrahaIN 2023). Although the farmers were allowed to stay, their struggle shows how detrimental institutional disregard can be to the sustenance of smallholders’ livelihoods. This is made even more so in Czechia, where farmers’ markets have only a short tradition (see Fendrychová and Jehlička 2018) and family farming is still recovering from socialist collectivization (see Zagata et al. 2019).

Municipalities could also help local farmers through tailored support for various food initiatives focused on short food supply chains and public procurement. Like farmers’ markets, CSAs and food cooperatives, such as the cooperative store Obživa, and other types of AFNs are also mentioned in Circular Prague 2030 to demonstrate citizen interest in local organic food, but without further specifying how these could be supported. Interviews (ID# 1, 13, 16) with food initiative representatives in the two cities, including, for example, the Brno based café and catering cooperative Tři Ocásci (ID# 3), showed that food initiatives occasionally receive municipal grants, which nonetheless rarely reflect their actual needs. The fact that several food initiatives use municipally owned premises is rather a game of chance than a result of targeted support.

The Czech umbrella organization promoting the ideals of agroecology, the food sovereignty movement, and CSAs is the Prague-based Association of Local Food Initiatives (AMPI; Asociace AMPI n.d.). It connects several organizations, initiatives, and smallholders in Czechia but also cooperates with foreign farmers and organizations with a similar mission across Europe. AMPI runs its own production-oriented community garden Kuchyňka, provides educational activities for schools, operates a farmers’ school for people interested in organic farming, and organizes an annual conference Živé zemědělství. AMPI also established a CSA coalition, which counts 33 CSAs in Prague and 7 in Brno, but currently lacks funds for its coordination (ID# 1, 23, 24).

Municipal actors occasionally invite AMPI to consult on topics related to CSAs and AFNs, including Prague’s circular strategy. One of AMPI’s experts would like to push for Prague’s membership in the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact but currently lacks the funding and personal capacities to lobby for this goal. As regards political lobbying and advocacy, AMPI closely cooperates with Hnutí DUHA (Friends of the Earth Czech Republic), an established environmental NGO, on lobbying within national and EU agricultural policy (ID# 30) and use agricultural strategies based on AMPI’s know-how (ID# 23). Hnutí DUHA also conducts a project called Živý region aimed at instigating the development of an organic region around Tišnov, a municipality about 25 km from Brno with links to the South Moravian region but not the Brno municipality, the organic region’s main prospective consumptive center (Živý region n.d.).

The most important Czech NGO promoting local organic food by public procurement is the Brno-based Skutečně zdravá škola. Inspired by the British program Food for Life, organized by the charity Soil Association, its goal is to improve the quality and culture of school feeding, integrate it into educational policy, and raise awareness regarding the social and ecological aspects of food consumption. So far, five hundred schools across Czechia have adopted the program, and Skutečně zdravá škola connects them with local farmers. The program’s expansion and scaling up are however constrained by the overall underdevelopment of the domestic agrarian market (see Grešlová Kušková 2013) and its insufficient capacity to produce local organic food (ID# 20), coupled with a lack of interest in the topic from the Czech socio-institutional environment and politicians. Skutečně zdravá škola therefore engages in advocacy at all scales of school and education governance. For instance, it also cooperates with Nesehnutí, a Brno-based NGO whose campaign Pestré jídelny strives to change the national legislation on public catering, particularly the prescribed nutritional requirements of food in school canteens, which many experts deem outdated, unhealthy, and unappetizing (ID# 20). Communication with politicians has however been quite disappointing:

Politicians are not interested. This topic cannot help them get more attention, or they don’t see it as acute. Prevention is not that cool.… We tried with many cities, regions; they usually reply, like, ‘Ok, great, but we cannot tell school principals what to buy, they are independent.’ I don’t know why they don’t want to support it. It’s a mystery. They don’t understand the context. Municipal councilors for education deal with education, but school feeding is marginal to them. They see no potential in it. We [Czechia] lack a food policy or feeding policy. We have nothing, no vision, nobody has vision in anything at all. Food does not interest anyone. (ID# 20)

A program supporting local organic food in municipally administered schools by public procurement was also under preparation by Prague’s municipal educational department between 2018 and 2022, but the status of preparations after municipal elections in 2022 is unknown.

Aside from disregarding support for short food supply chains and public procurement, most municipal actors also display a lack of concern for issues surrounding food insecurity among low-income social groups and their access to nutritious food. These issues however also receive relatively little attention from actors engaged in urban food alternatives in Prague and Brno, exemplified by the experience of the NGO Zachraň jídlo: Their effort to cooperate with Prague’s department of social affairs in finding opportunities for donations and the redistribution of leftover food portions to people affected by poverty and homelessness interfered with food insecurity not being the focus of either side of the collaboration (ID# 2):

We were in touch with the social department regarding lunch recipients and learned that Prague has no overview of local charities. We had to Google everything ourselves. The cooperation was futile. They do not deal with food at all. They deal with social aid, housing, social benefits, but food is not their primary focus. At most, charities cook soup. People must worry about food themselves.… I don’t know if social policy should deal with food. I am interested in waste. Our ambition is not to solve a social problem; we want to solve an ecological problem. (ID# 2)

Some of the representatives of food initiatives promoting short food supply chains and public procurement have relatively strong linking social capital. Municipalities occasionally support them via grants, consult with them, or negotiate over the use of public space. However, neither Prague nor Brno currently have political leaders who push for municipal involvement in socioeconomic aspects of the local food system transformation or food insecurity. In terms of bridging social capital, food initiatives are networked with each other and with some of the local and regional farmers, including the association of ecological farmers PRO-BIO. They meet at the annual conference Živé zemědělství and other events organized by AMPI. However, not all actors in urban food alternatives are integrated into these networks. Notably, these networks do not involve the Association of Farmers’ Markets, whose narrow focus on market organizing supposedly limits possible overlaps with the agendas of other local food alternatives according to one interviewed food initiative representative (ID# 24). As we show below, these networks also do not include allotment gardeners, who are generally not perceived as part of the food movement or the local food system transformation.

Degradation of food self-provisioning

The fourth relation that municipalities display towards urban food alternatives is degradation, which in both cities concerns allotment gardens despite their traditional role in food self-provisioning (see Jehlička et al. 2019, 2020). With the rising availability of international food supply chains after 1989, food self-provisioning quickly started to decline as did state-wide membership in Český zahrádkářský svaz, Czech gardeners’ association, which dropped from 420,000 to the current membership of 130,000 (ID# 9). In larger cities, allotment gardens started to be portrayed as incompatible with a vision of a modern Western metropolis and were gradually replaced by new development (see Gibas and Boumová 2020; Tóth et al. 2018). Only recently did this start to change in the context of new challenges, such as the climate crisis and the pandemic as well as the passing of the gardening law 221/2021 Coll., which recognizes gardening as a publicly beneficial activity and obligates local governments to support it (see Duží et al. 2021).

Despite these developments, allotment gardening receives only marginal attention in the urban food policies of both Prague and Brno. This neglect is likely due to their persistently ambivalent perception by municipal actors and urban planners. Since the 2010s, there have been repeated attempts by urban planners to simplify land-use change in selected allotments in planning documentation (Pixová and Plank 2022; ID# 6, 10, 14, 27) or to make allotment units more open to the public (ID# 5, 6, 9, 10, 15, 17, 22, 27, 32). Interviewed municipal actors argued that allotment gardens are allegedly losing their original purpose and are often used as illegal dwellings with swimming pools. Some of their users are also accused of polluting the surroundings with waste. Comparing them to community gardens, they see allotments as more isolated, individualistic, and not community-oriented or as spatial barriers that exclude other citizens from enjoying these green spaces for relaxation, leisure, and the like; therefore, they advocate the gardens be made more open to the public (ID# 4, 5, 22). Allotment gardeners are however afraid that interventions, such as cycling trails and public paths leading across their units, would threaten their food production and security (ID# 10, 27). They point out the close relationships and cooperation between units, the efforts of some units to be more open by organizing various public events, and the provision of allotments for community gardening (ID# 6, 9, 13, 27).

Out of all examined urban food alternatives, allotment gardeners have the weakest linking and bridging social capital, partly due to their approach to gardening as a hobby rather than as activism or part of the food system transformation. Except for their links to politicians who support gardening, the links of allotment gardeners to municipal departments are limited to tenancy issues dealt with by the property departments of municipal districts or to top-down debates instigated by urban planners. In Prague, experts have previously recommended establishing a municipal allotments coordinator (Miovská 2018) to mediate communication between allotment gardeners and municipal institutions. This coordinator could instigate a more inclusive participative discussion about the character of allotment gardens in the city; help enforce allotment unit regulations, the violation of which undermines the allotments’ public image (ID# 9, 10, 27); and potentially highlight their role in local food system transformation, food security, societal resilience, and so on. Neither Prague nor Brno have however established such a position, resulting in the persistence of poor communication, which often leads to tension, suspicion, and distrust, as well as gardeners feeling degraded, insecure, and unsupported by most contemporary governments (ID# 9, 10, 17, 27).

In terms of bridging social capital, there have been certain differences between Prague and Brno. In Prague, the willingness of allotment gardeners to engage in alliances with other civic actors has been limited by their conservative reluctance towards activism and often defensive position reinforced by the spreading of newer and, municipally, more supported trends in urban gardening. The quote below of a community gardener representative illustrates the tensions between them and allotment gardeners experienced at a debate organized by the Prague Institute of Planning and Development: “It is impossible to talk to them. We were in a debate with them, and they were very defensive about their opinions and their allotment units. It does not lead to their transformation—they are rigid. There have been efforts to open their units to the public, but they are worried about their stuff getting stolen. There is a general problem with trust” (ID# 17).

In Brno, on the other hand, the threat of allotment garden annihilation in central parts of the city brought allotment gardeners together with experts and other active citizens, who also included considerations about climate change, heat islands, and biodiversity protection (ID# 6). Community gardens are less widespread here, and some allotment units allegedly operate in a similar manner to community gardens and organize a lot of public events (ID# 6). Negotiations with the city nonetheless resulted in the relocation of part of the centrally-located allotments to the urban periphery, which according to one of the interviewed experts, was a suboptimal compromise attributed to the insufficiently radical approach of a gardener that was at that time also a municipal councilor (ID# 14).

Discussion: how urban food governance is constituted in relation to the local food system transformation in Prague and Brno

As regards the constitution of urban food governance in relation to the local food system transformation in Prague and Brno, we discuss here the municipalities’ four relations to different aspects of local food system transformation in connection to the values identified by Sonnino (2019) in progressive urban food governance, the linking and bridging social capital of urban food alternatives, and the role of these different aspects of local food system transformation in the corporate food regime and capitalist urban economy.

With consideration for a systemic approach, relocalization, translocalism, and participatory food governance, all aspects of the local food system transformation are important and should be integrated into a comprehensive food strategy and mainstreamed across other policies. Neither Prague nor Brno have political leaders promoting the creation of such a strategy. Some aspects of local food system transformation, such as tackling food insecurity with local food or membership in translocal networks, are completely absent in urban food policies and on the ground. The previous section also demonstrated the serious lag in terms of relocalization and participatory food governance, which is visible in the two municipalities’ selective approach to different urban food alternatives. As we will discuss below, prioritized urban food alternatives are those with strong linking social capital and that promote aspects of the local food system transformation that are compatible with the corporate food regime and capitalist urban economy.

The two examined municipalities embrace circularity, for example, composting for biofuel stations, as well as new trends in urban agriculture inspired by practices from abroad, such as community gardens. Compared to allotment gardens, community gardens require less space; are more transient, permeable, and flexible in their use; and represent an important part of postmodern social infrastructure, which provides citizens with access to urban greenery and leisure activities. Their ability to adapt to urban development, facilitate economic competitiveness (McCann et al. 2022; Walker 2016), green branding, and access to funds and investment (Braiterman 2011; García-Lamarca et al. 2022) makes them compatible with the capitalist urban economy. In line with these objectives, the Prague municipality also green lit experiments in biodiversity protection via urban ecological farming, which has not been further developed in terms of administration or by securing a stable outlet for farmer produce and links to consumers.

Municipalities in the two cities also disregard the socioeconomic aspects of the local food system transformation and food security. These could be supported through tailored grant schemes for short food supply chains, by public procurement, stable conditions for authentic farmers’ markets, or by implementing measures to protect cultivable land in the city from future development. This form of support would help urban ecological farmers compete within the global industrial food system and improve citizens’ access to healthy and nutritious food from local sources. Municipalities’ disregard for these agendas can be associated with the customary reliance on market forces, supply and demand, and corporate food charity (see Riches 2018). Such reliance points to a lack of understanding of the contradictions within the corporate food regime and the capitalist urban economy, due to which non-commercial food initiatives and small-scale organic farmers cannot compete with more powerful economic actors, both in terms of economies of scale and access to space. The disregard for these socioeconomic aspects concerning local organic food and food (in)security can also be associated with municipalities’ withdrawal from public services and social policies (see Harvey 1989), which is inherent to neoliberalism and its particularly effective implementation in post-socialist countries due to their efforts to rid themselves of their socialist past (Chelcea and Druţǎ 2016).

The disregard for food security combined with efforts to overcome the socialist past can be also associated with the degradation of allotment gardens in the two cities, despite their important role in food self-provisioning. From the perspective of urban governance within the capitalist urban economy, allotment gardens take up space that could be used for functions with a higher exchange value (see the section on urban food governance above) or, for real estate developers, to tackle the lack of green spaces in densifying compact city environments (see Haaland and van den Bosch 2015). From the perspective of the corporate food regime, the removal of allotment gardeners and their food self-provisioning would mean more dependence on global food supply chains.

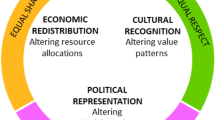

Our analysis has made clear that the strong linking and bridging social capital of actors engaged in urban food alternatives in both Prague and Brno has the potential to influence urban food governance only in aspects of the local food system transformation that do not challenge the corporate food regime and support the capitalist urban economy (see Fig. 1). More radical alternatives to the corporate food regime, regardless of the strength of their actors’ linking social capital, are disregarded or, at most, experimented with due to their capacity to contribute to biodiversity protection. The potential of food self-provisioning is either disregarded, reflected in the municipalities’ waiving coordination of allotment gardens, or degraded, which manifests through efforts to replace allotments with higher value development or by transforming their current use in ways less suitable for food self-provisioning. The potential to influence urban food governance is further diminished by low bridging social capital and the non-activist approach of the actors (allotment gardeners, organizers of farmers’ markets, and some urban ecological farmers). This could be overcome by their communication and cooperation with actors in urban food alternatives that comply with the definition of urban food movements due to their engagement in activism aimed at food system transformation. Such cooperation could help them build mutual solidarity and trust and define common objectives and the mutual benefits of collective action. This could ultimately lead to long-term coalition work based on co-created master frames that highlight the strategic role of urban food alternatives in food security, environmental sustainability, social justice, and the democratic transformation of the local food system, which is historically and culturally grounded and recognizes both local needs and the wider problems of the global industrial food system.

Conclusion

Our examination of urban food policies in Prague and Brno revealed that the values of relocalization and participatory governance are included, whereas a systemic approach and translocalism are largely absent. We then explored the way urban food governance is constituted based on municipal actors and institutional relations to different aspects of the local food system transformation. We analyzed potential links between these relations and the different levels of bridging and linking social capital among nongovernmental and grassroots actors in urban food alternatives. Our analysis revealed four types of relations: (1) embracement, (2) experimentation, (3) disregard, and (4) degradation. Which aspects of the local food system transformation municipalities embrace partially depends on the strong linking social capital of the nongovernment and grassroots actors who promote them, but also on these aspects’ compatibility with the corporate food regime and the urban capitalist economy. The municipalities most strongly embrace NGOs focused on waste reduction and community gardening whose strong linking social capital, acquired through their activist approach, allows them to speak legitimately in support of the remaining urban food alternatives, and their agenda is seen as innovative and potentially enhancing economic growth in the context of post-socialist cities. On the other hand, regardless of the strength of the nongovernment and grassroots actors’ linking social capital, the two cities disregarded aspects of the local food system transformation that represent more radical alternatives to the corporate food regime, and the actors engaging in them struggle to sustain themselves within the capitalist urban economy and global industrial food system. These more radical alternatives include public procurement and food donations to people in need as well as tailored support for food initiatives and authentic farmers’ markets providing short food supply chains. These however require more public intervention in relation to public assets, social services, and regulations, which post-socialist cities have been withdrawing from given the neoliberal restructuring and efforts to overcome their socialist past. This approach also affects ecological farmers on municipal fields, which Prague experiments with solely for environmental objectives and not due to food security concerns. Moreover, allotment gardens in both Prague and Brno continue to be degraded despite many of them still retaining their traditional role in food self-provisioning. Instead of protecting this cultivable land in the city and developing its food production potential, municipalities associate allotment gardens with the socialist past and with operating on vast areas of municipally owned land in a relatively permanent and inflexible mode. In comparison to newer trends in urban agriculture, allotment gardens are harder to replace with higher value development or to be transformed into publicly accessible greenery in a densifying city.

While we found that high linking social capital does not lead to municipalities’ embracing aspects of the local food system transformation that represent more radical alternatives to the status quo, we still suggest that a more systemic approach to local food system transformation could be achieved by strengthening bridging social capital and instigating coalition work between the currently fragmented urban food alternatives. Such a coalition would share access to opportunities, resources, and mobilization potential via collaboration, networking, experience sharing, synergies, and the formulation of clear common objectives and mutual benefits. Working collectively and in an inclusive way towards common objectives would increase trust and mutual understanding among different actors and empower currently marginalized actors, such as allotment gardeners, whose contribution to local food system transformation has yet to be acknowledged and developed. Using the strong linking social capital of certain actors in urban food alternatives in connection with collective power and common objectives could pressure urban governments to improve their urban food policies and become more active in their implementation, informed by progressive food governance in cities of the Global North. This would require a much more participatory approach to urban food governance and more radical interventions into other urban agendas, particularly land-use planning, which currently continues to threaten cultivable land in the city by prioritizing urbanization. While these suggestions seem impossible from the perspective of the status quo, we argue that urban food governance in Prague and Brno is, despite the current polycrisis context, not only insufficiently contributing to a local food system transformation but is, in fact, further reinforcing the unsustainable corporate food regime at the cost of urban food alternatives, eradicating existing and nascent facets of urban resilience.

Abbreviations

- AFN:

-

Alternative food network

- AMPI:

-

Association of Local Food Initiatives

- CEE:

-

Central and Eastern Europe

- CSA:

-

Community-supported agriculture

- EU:

-

European Union

- INCIEN:

-

Institute of Circular Economy

- NGO:

-

Nongovernmental organization

References

Alonso-Fradejas, Alberto, Saturnino M. Borras, Todd Holmes, Eric Holt-Giménez, and M. J. Robbins. 2015. Food sovereignty: convergence and contradictions, conditions and challenges. Third World Quarterly 36(3): 431–448. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1023567

Araghi, Farshad A. 1995. Global depeasantization, 1945–1990. The Sociological Quarterly 36(2): 337–368.

Asociace, A. M. P. I. n.d. Asociace místních potravinových iniciativ. https://www.asociaceampi.cz/. Accessed 7 Dec 2023.

Asociace farmářských tržišť. n.d. Asociace farmářských tržišť. https://www.aftcr.cz/. Accessed 1 Dec 2023.

Bauermeister, Mark Richard. 2016. Social capital and collective identity in the local food movement. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 14(2): 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/14735903.2015.1042189

Bhandari, Humnath and Kumi Yasunobu. 2009. What is social capital? A comprehensive review of the concept. Asian Journal of Social Science 37(3): 480–510. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853109X436847

Boukharaeva, Louiza Marcel Marloie. 2015. Family urban agriculture in Russia. Lessons and prospects. Springer International Publishing Switzerland.

Braiterman, Jared. 2011. City branding through new green spaces. In City branding, ed. Keith Dinnie. 70–81. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230294790_9

Brunner, Anna-Maria. 2022. The missing piece to food system’s socio-ecological transformation? Community-supported agriculture in Argentina. Master’s Thesis, Institute for Geography and Space Research. Graz, University of Graz.

Chelcea, Liviu, and Oana Druţǎ. 2016. Zombie socialism and the rise of neoliberalism in post-socialist Central and Eastern Europe. Eurasian Geography and Economics 57(4–5): 521–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2016.1266273

Clendenning, Jessica, Wolfram H. Dressler, and Carol Richards. 2016. Food justice or food sovereignty? Understanding the rise of urban food movements in the USA. Agriculture and Human Values 33: 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9625-8

Coulson, Helen, and Roberta Sonnino. 2019. Re-scaling the politics of food: place-based urban food governance in the UK. Geoforum 98: 170–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.11.010

Cousins, Joshua J., and Dustin T. Hill. 2021. Green infrastructure, stormwater, and the financialization of municipal environmental governance. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 23(5): 581–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2021.1893164

Dale, Ann, and Lenore Newman. 2010. Social capital: a necessary and sufficient condition for sustainable community development? Community Development Journal 45(1): 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsn028

Daněk, Petr, Lucie Sovová, Petr Jehlička, Jan Vávra, and Miloslav Lapka. 2022. From coping strategy to hopeful everyday practice: changing interpretations of food self-provisioning. Sociologia Ruralis 62(3): 651–671. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12395

Deloitte CZ. 2017. Koncepce Smart Prague do roku 2030. Prague. https://smartpra-gue.eu/files/koncepce_smartprague.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2023.

Dubová, Lenka, Jan Macháč, Alena, and Vacková. 2020. Food provision, social interaction or relaxation: Which drivers are vital to being a member of community gardens in Czech cities? Sustainability 12(22): 9588. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229588

Duží, Barbora, Naďa Johanisová, and Jan Vávra. eds. 2021. Zahrádkářské osady anebo proč neztrácet půdu pod nohama. Ostrava: Ústav geoniky AV ČR.

Fendrychová, Lenka, and Petr Jehlička. 2018. Revealing the hidden geography of alternative food networks: the travelling concept of farmers’ markets. Geoforum 95: 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.06.012

García-Lamarca, Melissa, Isabelle Anguelovski, and Kayin Venner. 2022. Challenging the financial capture of urban greening. Nature Communications 13(1): 7132. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34942-x

Gibas, Petr, and Irena Boumová. 2020. The urbanization of nature in a (post)socialist metropolis: an urban political ecology of allotment gardening. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 44(1): 18–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12800

Glowacki-Dudka, Michelle, Jennifer Murray, and Karen P. Isaacs. 2013. Examining social capital within a local food system. Community Development Journal 48(1): 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bss007

Grešlová Kušková, Petra. 2013. A case study of the Czech agriculture since 1918 in a socio-metabolic perspective— from land reform through nationalisation to privatisation. Land Use Policy 30(1): 592–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.05.009

Haaland, Christine, and Cecil Konijnendijk van den Bosch. 2015. Challenges and strategies for urban green-space planning in cities undergoing densification: a review. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 14(4): 760–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2015.07.009

Harvey, David. 1989. From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: the transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler B 71(1): 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583

Haysom, Gareth. 2015. Food and the city: urban scale food system governance. Urban Forum 26(3): 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-015-9255-7

iDNES. 2021. April 10. Supermarkety otevřené, ale trhy ne? Farmáři se brání ústavní stížností. https://www.idnes.cz/plzen/zpravy/farmar-trhy-namesti-republiky-covid-prijmy-ustavni-stiznost.A210408_602508_plzen-zpravy_vb. Accessed 1 Dec 2023.

INCIEN. n.d. Institut Cirkulární Ekonomiky. https://incien.org/. Accessed 1 Dec 2023.

Jehlička, Petr, and Joe Smith. 2011. An unsustainable state: contrasting food practices and state policies in the Czech Republic. Geoforum 42(3): 362–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.01.005

Jehlička, Petr, Tomáš Kostelecký, and Joe Smith. 2012. Food self-provisioning in Czechia: Beyond coping strategy of the poor: A response to Alber and Kohler’s Informal food production in the enlarged European Union (2008). Social Indicators Research 11(1): 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0001-4

Jehlička, Petr, Petr Daněk, and Jan Vávra. 2019. Rethinking resilience: home gardening, food sharing and everyday resistance. Revue Canadienne d’études du développement 40(4): 511–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2018.1498325

Jehlička, Petr. Miķelis Grīviņš, OaneVisser, and Bálint Balázs. 2020. Thinking food like an east European: a critical reflection on the framing of food systems. Journal of Rural Studies 76: 286–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.04.015

Jessop, Bob. 2010. State power: a strategic-relational approach. Cambridge: Polity.

Koc, Mustafa, and Japji Anna Bas. 2012. The interactions between civil society and the state to advance food security in Canada. In Health and sustainability in the Canadian food system: advocacy and opportunity for civil society, eds. Rod MacRae and Elizabeth Abergel, 173–205. Toronto: University of British Columbia.

Levkoe, Charles Z. 2014. The food movement in Canada: a social movement network perspective. The Journal of Peasant Studies 41(3): 385–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.910766

Lyons, Kristen, Carol Richards, Lotus Desfours, and Marco Amati. 2013. Food in the city: urban food movements and the (re)- imagining of urban spaces. Australian Planner 50(2): 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2013.776983

MacRae, Rod, and Kendal Donahue. 2013. Municipal food policy entrepreneurs. A preliminary analysis of how Canadian cities and regional districts are involved in food system change. Toronto Food Policy Council and Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute. https://capi-icpa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Municipal_Food_Policy_Entrepreneurs_Final_Report.pdf. Accessed 6 Mar 2024.

Magistrate of the Capital City of Prague. 2017. Strategie adaptace hl. m. Prahy na klimatickou změnu. Prague. https://adaptacepraha.cz/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/strategie_adaptace_cs_website.pdf. Accessed 26 Jul 2023.

Magistrate of the Capital City of Prague. 2021. Klimatický plán hlavního města Prahy do roku 2030. Praha na cestě k uhlíkové neutralitě. Prague. https://klima.praha.eu/data/Dokumenty/Dokumenty 2023/klimaplan_cz_2301_09_online.pdf. Accessed 8 Jul 2023.

Magistrate of the Capital City of Prague. 2022. Cirkulární Praha 2030. Strategie hl. m. Prahy pro přechod na cirkulární ekonomiku. Prague. https://klima.praha.eu/DATA/Dokumenty/Cirkularni-Praha-2030-Strategie-CE.pdf. Accessed 8 Apr 2023.

Magistrate of the City of Brno. 2016. Zásady pro rozvoj adaptací na změnu klimatu ve městě Brně s využitím ekosystémově založených přístupů. Východiska pro zpracování Strategie pro Brno 2050. Brno. https://ekodotace.brno.cz/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/P%C5%99%C3%ADloha-B-_-brno-adaptacni-strategie-fin.pdf. Accessed 23 Jul 2023.

Magistrate of the City of Brno. 2017. Strategie #brno2050. Brno. https://brno2050.cz/documents/. Accessed 16 Apr 2023.

Manganelli, Alessandra. 2020. Realising local food policies: a comparison between Toronto and the Brussels-Capital Region’s stories through the lenses of reflexivity and co-learning. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 22(3): 366–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1740657

Manganelli, Alessandra. 2022. The hybrid governance of urban food movements. Learning from Toronto and Brussels. Cham, Switzerland: Springer (Urban Agriculture).

Manganelli, Alessandra, Pieter van den Broeck, and Frank Moulaert. 2020. Socio-political dynamics of alternative food networks: a hybrid governance approach. Territory Politics Governance 8(3): 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2019.1581081