There's probably never going to be the awareness out there and the general acceptance that people at all income levels struggle with food….It's a double standard based on income, you make a lot of money, so you can't be hungry. Respondent #1

Abstract

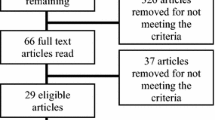

This is a community based research project using a case study of 20 people living in middle America who are food insecure, but do not use food pantries. The participants’ rate of actual hunger is twice that of food insecure community members who use food pantries. Since most of the participants are not poor, the Asset Vulnerability Framework (AVF) is used to classify causes of food insecurity. The purpose of the study is to identify why participants are food insecure and why they do not use food pantries. Findings reveal that the participants restrict the quality and quantity of food eaten as a strategy to manage their budget. Following AVF, this strategy allows them to offset lower returns to labor assets, cover rising costs of human capital investment, protect their two most important productive assets of housing and transportation, and compensate for household relationships that increase their vulnerability. In addition, food insecurity itself inhibited social capital formation, further increasing vulnerability. The main reasons the participants do not use food pantries is to protect their social capital assets: almost all of the participants hid their hunger from colleagues, friends, relatives, and even the people they lived with. The participants described fear of societal shaming and blaming as motivations for hiding their hunger. However, using food pantries could reduce their food insecurity. Therefore, there was a feedback loop between food insecurity and social capital: food insecurity reduced social capital and efforts to protect social capital prevented participants from improving food security by using food pantries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The poverty line was determined in the 1960s when households spent about one-third of their income on food. Since then, the US government has determined poverty by multiplying the cost of a food basket by three. However, the relative price of food has fallen versus other expenses, particularly housing. This means that the current poverty line is one-half to a third of what would allow households to cover basic expenses.

Please indicate whether you agree with this statement, “Within the past 12 months we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more.” Please indicate whether you agree with this statement, “Within the past 12 months the food we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to get more.”

Many food pantries lack refrigeration and therefore are limited to offering shelf-stable, often processed foods.

Abbreviations

- AVF:

-

Asset Vulnerability Framework

- ERS:

-

Economic Research Service

- SNAP:

-

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

- USDA:

-

United States Department of Agriculture

References

Basiotis, P. P., and Lino, M. 2003. Food insufficiency and prevalence of overweight among adult women. Family Economics and Nutrition Review 15 (2): 55–57.

Caraher, M., and J. Coveney, Eds. 2016. Food poverty and insecurity: International food inequalities. Switzerland: Springer.

Coleman-Jenson, A., M.P. Rabbitt, C. Gregory, and A. Singh. 2015. Household food security in the United States in 2014, ERR 194. US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, September 2015. http://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err194.aspx. Accessed 29 Aug 2016.

Daponte, B. O., and S. Bade 2006. How the private food assistance network evolved: interactions between public and private responses to hunger. Non profit and Voluntary Quarterly 35 (4): 668–690.

Economic Research Service, Economic Research Service (USDA ERS). 2016. Survey questions used by USDA to assess household food security. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/measurement.aspx#survey. Accessed 13 June 2016.

Edin, K., M. Boyd, J. Mabli, J. Ohls, J. Worthington, S. Greene, N. Redel, and S. Sridharan. 2013. SNAP food security in-depth interview study. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Research and Analysis, March 2013. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/SNAPFoodSec.pdf. Accessed 30 Aug 2016.

Gundersen, C., and Ribar, D. 2011. Food insecurity and insufficiency at low levels of food expenditures. Review of Income and Wealth 57 (4): 704–726.

Gundersen, C., B. Kreider, and J. Pepper 2011. The economics of food insecurity in the United States. Economic Perspectives and Policy 33 (3): 281–303.

Hanson, K. L., and L. M. Connor 2014. Food insecurity and dietary quality in US adults and children: a systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 100: 684–692.

Hernandez, D. C. 2015. The impact of cumulative family risks on various levels of food insecurity. Social Science Research 50: 292–302.

Laraia, B. A. 2013. Food insecurity and chronic disease. Advances in Nutrition 4: 203–212.

Moser, C. O. N. 1998. The asset vulnerability framework: Reassessing urban poverty reduction strategies. World Development 26 (1): 1–19.

Natale, M. E. and D. A. Super. 1991. The case against the Thrifty Food Plan as the basis for the food component of the AFDC standard of need. Clearinghouse Review 86. http://povertylaw.org/clearinghouse/article/case-against-thrifty-food-plan-basis-food-component-afdc-standard-need. Accessed 6 Sept 2016.

Proctor, B. D., J. L. Semega, and M. A. Kollar. 2016. Income and poverty in the United States: 2015. US Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-256. http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p60-256.pdf. Accessed 15 Sept 2016.

Schanzenbach, D. W., L. Bauer, and G. Nanzt. 2016. Twelve facts about food insecurity and SNAP. The Hamilton Project, The Brookings Institute. http://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/twelve_facts_about_food_insecurity_and_snap. Accessed 30 Aug 2016.

US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (USDA ERS). 2015. Definitions of food security. http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security.aspx. Accessed 13 June 2016.

US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service (USDA ERS). 2016. Survey questions used by USDA to assess household food security. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/measurement.aspx#survey. Accessed 13 June 2016.

Weinfield, N.S., G. Mills, C. Borger, M. Gearing, T. Macaluso, J. Montaquila, and S. Zedlewski. 2014. Hunger in America 2014: national report prepared for Feeding America. http://help.feedingamerica.org/HungerInAmerica/hunger-in-america-2014-full-report.pdf?s_src=W175ORGSC&s_referrer=yahoo&s_subsrc=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.feedingamerica.org%2F&_ga=2.29145400.585988428.1494963252-845492206.1494963226. Accessed 16 May 2017.

Wilde, P. E., and J. N. Peterman 2006. Individual weight change is associated with household food security status. Journal of Nutrition 136: 1395–1400.

Yellen, J. L. 2016. The Federal Reserve’s monetary policy toolkit: past, present, and future. At Designing resilient monetary policy frameworks for the future, a symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August 26, 2016. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20160826a.htm. Accessed 6 Sept 2016.

Zepeda, L. and A. Reznickova. 2016. Potential demand for local fresh produce by mobile markets. Selected paper at the 2016 American Agricultural Economics Association meetings, Boston. http://www.localandorganicfood.org. Accessed 30 Aug 2016.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Gina Wilson of Second Harvest Foodbank of Southern Wisconsin for asking me to do this study and to Second Harvest for funding transcription and participant payments. I extend my gratitude to Kathryn Carroll for helping with recruitment of participants and to Anna Reznickova for conducting four of the interviews. I am extremely grateful to the participants of this study for sharing their stories.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1 Interview question guide

-

1.

Tell me about a typical dinner, you can use last night if that was typical.

Potential follow-up questions: What did you eat? Who prepared it? Where was it prepared? Who did you eat with?

-

2.

Tell me about where you get food from.

Potential follow-up questions: How often do you shop? Where do you shop? What kinds of things do you buy?

-

3.

Are there things you are unable to get that you would like to eat? If so, what are they?

Potential follow up questions: Why are you unable to get them? What would help you get the food you would like?

-

4.

Tell me about an experience you had in the last 12 months when you either worried you would run of food or ran out of food.

Potential follow-up questions: What did you do? What could have prevented it?

-

5.

Why do you think people go to food pantries?

Potential follow-up questions: who are they, what are they like, why do they go?

-

6.

Tell me about people you know who go to food pantries.

Potential follow up questions: Who are they, what are they like, why do they go? What do they tell you about food pantries?

-

7.

Why do you think people don’t go to food pantries?

-

8.

What would cause you to go to a food pantry? What would keep you from going to a food pantry?

Appendix 2 Summary of participant characteristics

-

1.

White male, professional, works full-time, married

-

2.

White female, professional, works full-time

-

3.

White female professional, single, works full-time, had been unemployed, disabled, large medical bills

-

4.

White female professional, single, unemployed, disabled, gluten-intolerant, large medical bills

-

5.

White female undergraduate, had been unemployed

-

6.

White male undergraduate, has two part-time jobs, donates plasma, dumpster dives, health problems

-

7.

White female undergraduate, gluten intolerant, health problems, large healthcare bills

-

8.

White male student taking classes to prepare for graduate school, two part-time jobs

-

9.

Hispanic female graduate student, has assistantship, works 20–25 h a week

-

10.

White male graduate student, no assistantship, works at restaurant, takes food home

-

11.

White female undergraduate, works part-time, mother is dead, sends money to her father

-

12.

White male, works full-time, supports partner and child

-

13.

White female lives with 19-year-old son, she is on disability, he is unemployed

-

14.

Hispanic female, professional, works full-time, single

-

15.

White male, 60, unemployed construction worker, homeless

-

16.

White female, unemployed.

-

17.

White/African-American female, works full-time, was unemployed and disabled, large medical bills, lives with room-mates

-

18.

White female, 29, vegetarian, gluten intolerant, works full-time, injured at work was disabled, unpaid leave, large medical bills, lives with boyfriend

-

19.

White female, lives with wife and 15-year-old son, professional, works full-time, professional, wife was unemployed

-

20.

White female, 26, lives with boyfriend and mother-in-law, took time off work to care for mother-in-law, works full-time, professional

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zepeda, L. Hiding hunger: food insecurity in middle America. Agric Hum Values 35, 243–254 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-017-9818-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-017-9818-4