Abstract

To determine the effect of distributed practice (spacing out of study over time) and retrieval practice (recalling information from memory) on academic grades in health professions education and to summarise a range of interventional variables that may affect study outcomes. A systematic search of seven databases in November 2022 which were screened according to predefined inclusion criteria. The Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale-Education (NOS-E) were used to critically appraise eligible articles. A summary of interventional variables includes article content type, strategy type, assessment type and delay and statistical significance. Of 1818 records retrieved, 56 were eligible for inclusion and included a total of 63 experiments. Of these studies, 43 demonstrated significant benefits of distributed practice and/or retrieval practice over control and comparison groups. Included studies averaged 12.23 out of 18 on the MERSQI and averaged 4.55 out of 6 on the NOS-E. Study designs were heterogeneous with a variety of interventions, comparison groups and assessment types. Distributed practice and retrieval practice are effective at improving academic grades in health professions education. Future study quality can be improved by validating the assessment instruments, to demonstrate the reliability of outcome measures. Increasing the number of institutions included in future studies may improve the diversity of represented study participants and may enhance study quality. Future studies should consider measuring and reporting time on task which may clarify the effectiveness of distributed practice and retrieval practice. The stakes of the assessments, which may affect student motivation and therefore outcomes, should also be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health professions education (such as medicine, physiotherapy, and clinical psychology) covers a large amount of theoretical and practical content over a broad range of subjects, to prepare students for entering the workplace. Distributed practice (spaced practice) is spacing out study over time as opposed to massing (or cramming) study. Retrieval practice is the act of recalling information from memory, such as using practice tests. Both strategies have been reported as effective at improving knowledge retention in a number of contexts and are thus considered to benefit health professions education (Dunlosky et al., 2013). These strategies are also considered ‘desirable difficulties’, coined to represent study strategies that feel challenging but are often more effective than those that feel easy (Bjork & Bjork, 2011). Previous research in health professions education demonstrates that students and educators often hold misconceptions about what are effective study strategies, and commonly use strategies that are considered less effective (Piza et al., 2019). Even with a clear concept of effective study strategies, students during a unit of learning will often revert to less effective strategies than originally intended (Blasiman et al., 2017). Exploring the effectiveness of distributed practice and retrieval practice in health professions education is therefore indicated to help guide students and educators.

Distributed practice in previous research is often compared to no intervention, massed study, or varying the inter-study interval (ISI). ISI is the interlude separating different study sessions, and consists of three main types: expanding, contracting and equal. Expanding schedules refer to the gradual increase in ISIs, contracting schedules are the gradual decrease in ISIs and equal schedules are equally spaced ISIs, with research demonstrating varying effectiveness (Gerbier et al., 2015; Karpicke & Roediger, 2007, 2010; Küpper-Tetzel et al., 2014). The overall length of an ISI also affects learning outcomes, with increasing ISIs up to 29 days demonstrating improved long term memory outcomes when compared to shorter ISIs (Cepeda et al., 2006; Rohrer, 2015). Furthermore, as the retrieval interval increases, concurrently increasing the ISIs improves outcomes compared to shorter ISIs (Cepeda et al., 2008).

Retrieval practice includes three main types, each varying in cognitive load: recognition, cued recall, and free recall. Recognition questions, such as multiple-choice, allow students to select an answer that they recognise but may have been unable to recall without the suggestion. Cued recall questions refer to fill-in-the-blank and short-answer questions which increase cognitive demand, and free recall is considered the most cognitively demanding, as no question cue, or answer suggestion is provided (Adesope et al., 2017). Retrieval practice that increases cognitive demand, correlates with improves assessment scores (Adesope et al., 2017; Rowland, 2014) and retrieval practice questions that are identical to assessment questions are reported to be more effective than non-identical retrieval practice questions (Veltre et al., 2015).

The comparison groups for retrieval practice can include no study or normal class, restudying (rereading or rewatching content), concept mapping, or comparisons between varying types of retrieval practice, with retrieval practice generally demonstrating superior outcomes in all comparisons (Adesope et al., 2017). Including feedback with retrieval practice has shown mixed results, with positive outcomes found in lab-based studies, but null effect in classroom-based studies (Adesope et al., 2017). Further, some studies showed a reduced effect when feedback was added to retrieval practice (Kliegl et al., 2019; Racsmány et al., 2020). Longer retrieval intervals, the interval between practice and final assessment, favours retrieval practice over restudy (Rowland, 2014). One specific use of retrieval practice is pre-questions, which is the retrieval of information that has yet to be covered, and may also enhance retention of that material (Little & Bjork, 2016; Richland et al., 2009).

Time on task is also an important variable to track in comparison trials. Increasing time on task has shown a strong correlation with improved academic grades (Chang et al., 2014). Therefore, this could be a confounding factor if distributed practice or retrieval practice time on task does not equal that of the comparison or control group. Controlling for time on task in trials will reduce the risk of this factor confounding results.

The stakes of an assessment may also be relevant, defined as formative assessments (or no-stakes assessments) and summative assessments which can be low-stakes (low weighting or grade) or high-stakes, such as exams that must be passed to complete a unit. Mixed outcomes have been found when increasing the stakes of assessments. High stakes may increase the motivation to engage with the learning strategy, thereby improving outcomes (Phelps, 2012). However, increased stakes may induce test anxiety, thereby reducing final performance (Hinze & Rapp, 2014). Learning setting is also important, with interventions that are applied to assessments and coursework relevant to educators, whereas interventions applied to self-directed learning, such as homework are also applicable to students.

How distributed practice and retrieval practice are implemented may affect the outcome. Therefore, this review also summarises key implementation variables, including type of retrieval practice and distributed practice, type of comparison group, the inclusion of feedback with retrieval practice, the retrieval interval, time on task and the stakes of an assessment. Included in this review is also a critical appraisal of the methodology quality of studies and therefore the strength of the results. No current systematic review appraises the distributed practice and retrieval practice literature in a health professions education context, however, there has been related work with a scoping review of spaced learning in health professions education (Versteeg et al., 2020), a systematic review of instructional design in simulation-based education (Cook et al., 2013) and a review of brain-aware teaching strategies for health professions education (Ghanbari et al., 2019).

The purpose of this review is to determine the effect of distributed practice and retrieval practice on academic grades in health professions education. This review will highlight directions for future research and guide educators and students towards more effective learning strategies to assist in improving knowledge acquisition.

Methods

A systematic review method was applied according to the PRISMA guidelines to answer the review question: Are distributed practice and retrieval practice effective learning strategies at improving academic grades in health professions education?

The inclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1 and articles were only included from peer reviewed journals. Both control and comparison studies were included in this review, however case series were excluded. Studies were excluded if the intervention, control, or comparison groups did not have equivalent outcome measures. Laboratory studies were excluded to improve the applicability of the research to health professions education. Content relevant to tertiary healthcare programs was searched via healthcare professions, which are included in the search criteria listed below. These were further screened for applicability, with graduate programs and studies that included non-clinical content, such as cognitive psychology studies excluded. There were no exclusion criteria for comparison groups, therefore both control groups and a variety of comparison groups were included in this review. Studies were excluded if the only outcome measure was students’ subjective rating of their performance, as this is often an inaccurate judgement of learning (Dunlosky & Rawson, 2012). Academic grades were therefore a required outcome measure for inclusion, despite satisfaction, judgement of learning and engagement also benefitting from both distributed practice and retrieval practice (Browne, 2019; Bruckel et al., 2016; Karpicke, 2009; Son & Metcalfe, 2000).

Search strategy

Identification

The population and intervention inclusion criterion were used to create search terms, including alternate terms such as spaced practice for distributed practice. This method was applied to the databases of EBSCOhost (Education Source, CINAHL Complete, ERIC, MEDLINE Complete, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection), Web of Science, and Scopus. Search terms: (health OR physiotherap* OR “physical therap*” OR “allied health” OR pharmacy OR medic* OR nursing OR “occupational therap*” OR “speech patholog*” OR dentist* OR psycholog*) AND (student* OR undergrad* OR postgrad* OR tertiary OR universit*) AND (“retrieval practice” OR “retrieval-based practice” OR “spaced practice” OR “distributed practice”) in November 2022. Search mode: EBSCOhost ‘find all my search terms’, Web of Science ‘TOPIC’, Scopus ‘article title, abstract and keywords’.

Screening, eligibility, and inclusion

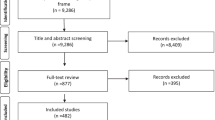

After removal of duplicate articles, the remaining articles were screened for eligibility by title, then abstract and finally the full article against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The results of this screening process are displayed in Fig. 1, with the most common reasons for exclusion being non-tertiary health professions education, such as other non-clinical healthcare disciplines, qualified healthcare professions education, or clinical healthcare patient populations.

Figure 1

Critical appraisal

The Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale-Education (NOS-E) were used to critically appraise the eligible articles (Cook & Reed, 2015). One review of these appraisal methods suggests that whilst the MERSQI focuses on more objective design issues, the NOS-E is more subjective, but covers more information on the implications of study design. They therefore complement each other when used together (Cook & Reed, 2015). See ‘Table 1’ of the article by Cook, David A. MD, MHPE and Reed, Darcy A. MD, MPH for further information of the criteria definitions and scoring system of the MERQI and NOS-E (Cook & Reed, 2015).

Summary of articles

The summary will also highlight the key variables described in the introduction. Statistical significance will only briefly spotlight significant findings and for studies that compare multiple timepoints, the statistical significance summary will focus on the longest retrieval interval.

Results

The MERSQI score for each included study is provided in Table 2 and NOS-E score in Table 3. The studies’ variables, and statistical significance are summarised in Table 4.

Summary of articles

Of the 56 studies, some studies conducted more than one experimental intervention. Therefore, a total of 63 experiments are included in this review. Of these experiments, 43 demonstrated a significant positive effect for distributed practice and/or retrieval practice compared to massed practice, rereading, normal class, or no intervention. One study demonstrated a negative effect for distributed practice. Retrieval practice alone was most studied (n = 33), the spacing out of retrieval practice was commonly studied (n = 16) and distributed practice alone was less frequently studied (n = 14).

The most common units were introductory psychology (n = 16), physiology (n = 8), anatomy (n = 6) and anatomy & physiology (n = 4). Interventions were generally classroom based rather than homework based. The content from one class only was assessed in fifteen studies and the retrieval interval reported for these studies was generally seven days (five days for two studies). Many other studies were longer, covering content of an entire unit, the retrieval interval based on the final exam. Nine studies included an assessment of knowledge post unit completion. Interventions and comparison groups varied widely.

Recognition or cued recall were the most common retrieval types with only a few studies using free recall. Four studies compared types of retrieval practice and predominantly found fill-in-the-blank words more effective than fill-in-the-blank letters, short answer questions more effective than fill-in-the-blank, and free recall more effective than recognition. Feedback was common in retrieval practice interventions, however some studies failed to report on this at all.

Of the distributed practice studies, five compared types of distributed practice and found an expanding schedule more effective than an equal schedule in two studies but no difference in one study, an expanding schedule more effective than contracting and equal schedules in one study, and a contracting schedule more effective than expanding and equal schedules in another study. An expanding schedule was superior in three out of the five studies.

Time on task was frequently not reported, those studies that did measured time on task often did not control for this variable. Assessments were most frequently summative (n = 24) compared to formative (n = 14). Studies that used a small grade, for example, 2%, as incentive to complete the assigned work and was independent of final assessment outcomes, were included as formative assessment. Notably, many studies did not report on the stakes of assessments at all (n = 25), nor what percentage grade was assigned to the assessment. Two studies compared assigned versus optional homework and found assigned homework to be more effective (Janes et al., 2020; Trumbo et al., 2016). Five summative and two formative assessments showed no effectiveness of distributed practice and/or retrieval practice.

Study quality

Of the studies that completed multiple experiments, those that used the same methodology in either the MERSQI or NOS-E are only rated once, however, if the methodology differed, they were rated separately under the relevant experiment. Within-subject studies were considered randomised if the order of interventions was randomised so that time until assessment was averaged over the conditions. The between-subject studies most often used the same community to select their comparison group, and historical cohorts were generally described as having the same class structure and content. Some studies did not mention or require ethical approval, and therefore did not include informed consent proceeding their randomisation. This resulted in a few of these studies not reporting any allocation concealment, and therefore scoring lower on the NOS-E. Non-randomised studies occasionally recorded subject characteristics, such as gender, age, and ethnicity, but infrequently recorded baseline scores such as a pre-test and rarely controlled for these characteristics with a statistical covariate analysis resulting in a lower comparability of groups.

Most studies were only sampled from a single institution. The retention of participants, which is scored in both the MERSQI and NOS-E was generally high. The representativeness of the intervention group was scored low in some studies, most often because the numbers were not reported. Blinding of assessment was scored high on most studies in the NOS-E, as most assessments were multiple-choice questions. No experiments included outcomes of ‘Behaviours’ or ‘Patient or healthcare outcomes’.

On the MERSQI, the ‘Validity evidence for evaluation instrument’ was generally scored low, with only two studies reporting on internal structure demonstrating reliability. Many studies did not report the source of content for their assessment, whether from a textbook, or expert. The data analysis was generally sophisticated and appropriate for all but a couple of studies.

Discussion

This systematic review was undertaken to determine the effect of distributed practice and retrieval practice on academic grades in health professions education and to summarise a range of interventional variables that may affect study outcomes. This review indicates that distributed practice and/or retrieval practice are effective in most of the studies, when compared to several comparison or control groups, at improving test and examination scores, and is therefore a worthwhile learning strategy to consider in health professions education. Only one study showed a negative effect for distributed practice, but several variables such as time on task and test delay may explain this result (Cecilio-Fernandes et al., 2018). Although retrieval practice was the most studied learning strategy, many retrieval practice studies did not report on what content was being reviewed. Therefore the number of spacing out of retrieval practice interventions may be underreported if content from numerous weeks was being reviewed.

Interventions were generally applied to specific units of learning, rather than entire programs or content matter. Studies of these introductory units did not always include clear healthcare program information; however, it was assumed that these introductory units are a requirement for many health professions programs.

Not reporting the time on task for intervention and comparison groups was common in this review and is a strong confounding factor limiting the strength of the results. A false positive may occur when there is more time on task or a false negative when there is less time on task. One study reported a higher time on task for the distributed condition compared to the massed condition, but still found no significant benefit (Kerdijk et al., 2015). In this case, having students distribute their practice would be particularly ineffective, and a poor use of time. Whereas another study showed a higher time on task for the restudy group compared to the retrieval group, and even though they spent less time studying, the retrieval group had significantly superior outcomes (Schneider et al., 2019). This would then be considered a particularly effective learning strategy in this context, not to mention an efficient strategy. Conclusions may be erroneously drawn about the effectiveness of the learning strategies when time on task is not monitored and should be a focus of future research.

There are many variables mentioned in this review that could be affected by an overarching variable of student motivation. These include whether interventions were classroom-based or homework-based, optional homework or assigned homework, and summative or formative assessments.

Classroom-based interventions may result in students having less competing distractions and challenges with time management than in a home environment for homework-based interventions (Xu, 2013). Although only a couple of experiments mentioned online homework specifically, it is important to be aware that a face-to-face intervention compared to an online intervention may affect learning. Many health professions programs changed to elements of online learning during and post COVID (Kumar et al., 2021; Naciri et al., 2021; Schmutz et al., 2021). Results are mixed as to which may be more effective for student, but issues around student motivation, engagement and academic integrity may be relevant (Miller & Young-Jones, 2012; Platt et al., 2014). This will be an area to watch as more studies report on the effect of online learning compared to face-to-face learning in general, as well as with distributed practice and retrieval practice.

The two studies that found assigned homework to be more effective than optional homework may also be affected by student motivation (Janes et al., 2020; Trumbo et al., 2016). Assigning compulsory homework is an external motivation that will likely rise to the top of a student’s priority list compared to optional homework. To better understand the effect of motivation in these studies, measuring time on task for each group would give further insight. One study did not measure time on task (Janes et al., 2020), and the other found that on average, the more effective assigned homework group completed approximately 5.5 times the amount of time on task compared to the optional homework group. Therefore, although assigned homework is more effective, this is likely due to the student’s motivation to complete it and spend more time on the task.

There was no clear benefit in this review when comparing summative and formative assessments. It was a common area of missing information in the experiments and the study methodologies varied significantly. Further research should include this information and the percentage of the grade, as well as other factors that may explain the variability in outcomes, such as time spent studying and test anxiety.

There were also three interventions that used the placement of exams as distributed retrieval practice. Considering that most exams are a requirement to complete a unit and progress through a degree, this would be considered a high external motivation to increase effort to study and recall information, and therefore improve the retrieval practice effect. Two of these studies assessed increasing the number of exams, with one showing no significant benefit (Kerdijk et al., 2015) and the other showing that increasing the number of exams was a significant benefit (Keus et al., 2019). The time on task was not reported for either study, however it likely increased as the number of assessments increased. The time that students spent studying for each exam was also not reported, and likely increased due to the external motivation of a summative assessment. The third study looked at a post final exam assessment of knowledge retention and found that including content in the final exam increased the likelihood of improved long-term knowledge retention (Glass et al., 2013). This study also highlights the pitfalls of assessments in general, as many students may cram for an assessment and show positive outcomes but forget the knowledge in the long term. Overcoming this challenge may involve future research including more long-term, post-unit formative assessments that students don’t necessarily know about in advance, to get a clear gauge on the effectiveness of different learning strategies.

Student motivation is a complex, multifactorial topic and is not heavily addressed in this paper. It was not considered by any of the interventional experiments included in this review either. However, it may be an important variable to consider in future research, as students that participate in an intervention will of course benefit from these learning strategies more than students that chose not to participate, or only partially participate.

Study duration was another factor that may affect replication in ‘real world’ classrooms. Many studies only had a single intervention point which was then assessed a week later. This is frequently reported in prior research (Karpicke & Blunt, 2011; McDaniel et al., 2009) and research demonstrates that forgetting new content may plateau by one week (Loftus, 1985). The longer duration studies, however, may be more relevant to educators’ goals of long term memory in health professions education. This long term memory is needed for the scaffolding of information in future units (Belland et al., 2017) and to ultimately be applied in students professions post-graduation. Interventions and comparison groups varied widely, including studies that educated students on the benefits of distributed practice and/or retrieval practice as the intervention (n = 5). The goal of this type of intervention may be to improve students own self-directed studying. Considering educators limited time (Inclan & Meyer, 2020) and students reporting low use of these strategies in previous research (Persky & Hudson, 2016), this could be an interesting direction for future research. This future research should aim to students’ self-directed learning durations and type, as well as academic scores, to best understand if this is an effective strategy or not.

This paper supports the theory that increasing cognitive demand improves outcomes (Adesope et al., 2017), with short answer and free recall questions showing greater benefit than recognition questions. An expanding schedule was the most effective inter-study interval, however study methodology such as retrieval interval differed between studies and the results are mixed. Further research is needed to determine the most effective inter-study interval. There was insufficient information to determine if providing feedback with retrieval practice was more effective than not providing feedback, as there were no comparison groups directly assessing this, and most studies either provided feedback, or did not report on it at all. Future research has many avenues to understand this further, including the timing of feedback, with delayed feedback showing superior outcomes on other research (Butler et al., 2007).

Study quality

The MERSQI and NOS-E scores in this review were affected by the inclusion criteria, which avoided low scoring in the ‘Study design’, ‘Type of data’ and ‘Outcome’ sections. (Cook & Reed, 2015). Between-subject studies were most commonly unable to be randomised when comparison groups were entire classes. A benefit of the within-subject design is an identical population comparison group, which therefore scored well in the NOS-E.

Most studies will have limited the generalisability of their results considering they were only sampled from a single institution. However, this is also simpler for researchers to control for variables such as content delivered and assessed. Considering that no two units are the same, a complete replication of these findings in future research or in educators’ classrooms cannot be expected, however it does still provide some good direction for future application of these strategies.

Studies that did not receive a full score for participant retention were generally large class sizes of an introductory unit, which often have higher student attrition (Trumbo et al., 2016) or studies that were of a longer duration (Dobson, 2013). High participant retention was noted in interventions that only addressed a single class, most likely due to the short duration of the study (one week). Incentives such as small amounts of course credit or money also likely improved retention in other studies.

No experiments had outcomes that included ‘Behaviours’ or ‘Patient or healthcare outcomes’, likely due to the nature of undergraduate education studies. Undergraduate health professions education does not generally apply learning to a patient population in a clinical context, compared to graduate training and continuing professional development (Chen et al., 2004). However, even in continuing professional development environments, assessing learning outcomes via patient or healthcare outcomes is poorly researched (Chen et al., 2004; Prystowsky & Bordage, 2001).

The low ‘validity evidence for evaluation instrument’ found in most studies, will limit the ability to generalise these outcomes into other settings, such as future high stakes examinations and professional practice (Beckman et al., 2005). Many studies did not report the source of content for their assessment, whether from a textbook, or expert. This domain of the MERSQI is commonly scored poorly in previous research (Reed et al., 2007). The time and resources required to validate an assessment is likely the cause of this finding, however future research should report on the source of content for assessment where possible. The high score of data analysis in this review is a domain that is typically scored high in other research (Reed et al., 2007).

Recommendations

Based on this systematic review, educators and students may find distributed practice and retrieval practice effective in their own classroom or self-directed study context at improving academic grades. Foundational units, such as introductory psychology, anatomy, and physiology, could particularly benefit from these learning strategies. Educators could trial increasing the number of formative and summative assessments as a method of providing students with retrieval practice and distributed practice. This may improve academic grades and long-term memory of content for future units and professional practice. Expanding the distributed practice schedule may provide greater benefits compared to equal or contracting schedules. Free-recall or cued recall questions are likely to improve learning more than recognition questions such as multiple choice. Educators could also educate students on the benefits and practical applications of distributed practice and retrieval practice, which may improve self-regulated learning. Students could be encouraged to trial spacing out their revision, writing their own retrieval questions or sourcing questions from peers and external sources to improve their academic grades and long-term memory.

Limitations

Due to the heterogeneity of studies, a meta-analysis is not possible. A single reviewer scored the MERSQI and NOS-E of the included papers and this may increase the risk of errors. The study quality instruments of both the MERSQI and NOS-E do not cover all aspects of study quality; elements that were missing include trial registration, which aims to reduce many types of bias, such as citation bias (Pannucci & Wilkins, 2010) and inflation bias or ‘p hacking’ (Head et al., 2015). Summarising the key variables and statistical significance from each study is also simplistic and can therefore be misleading if read in isolation. This review should be used to help navigate readers to source articles for the full picture, and not be used as evidence alone of a study’s significance.

Conclusion

Distributed practice and retrieval practice are often effective at improving academic grades in health professions education. Of the 63 experiments, 43 demonstrated significant benefits of distributed practice and/or retrieval practice over control and comparison groups. Study quality was generally good with an average of 12.23 out of 18 on the MERSQI and an average of 4.55 out of 6 on the NOS. Key areas of study quality improvement are the validity of assessment instruments and the number of included institutions within a study. Future studies should consider measuring and reporting time on task which may illuminate the efficiency of distributed practice and retrieval practice. The stakes of the assessments, which may affect student motivation and therefore outcomes, should also be considered. Educators can note that the use of multiple exams, particularly if they are summative, will result in most students participating in the spacing out of retrieval practice. Introductory psychology, anatomy and physiology educators and students have a variety of retrieval practice and distributed practice applications that could be trialled and may successfully transfer to their own contexts.

References

Adesope, O. O., Trevisan, D. A., & Sundararajan, N. (2017). Rethinking the use of tests: A Meta-analysis of practice testing [Article]. Review of educational research, 87(3), 659–701. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316689306.

Amabile, A. H., Nixon-Cave, K., Georgetti, L. J., & Sims, A. C. (2021). Front-loading of anatomy content has no effect on long-term anatomy knowledge retention among physical therapy students: A prospective cohort study. BMC medical education, 21(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02925-z.

Anders, M. E., Vuk, J., & Rhee, S. W. (2022). Interactive retrieval practice in renal physiology improves performance on customized National Board of medical examiners examination of medical students. Advances in Physiology Education, 46(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00118.2021.

Beckman, T. J., Cook, D. A., & Mandrekar, J. N. (2005). What is the validity evidence for assessments of clinical teaching? Journal of general internal medicine, 20(12), 1159–1164. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0258.x.

Belland, B. R., Walker, A. E., & Kim, N. J. (2017). A bayesian network meta-analysis to synthesize the influence of contexts of scaffolding use on cognitive outcomes in STEM education. Review of educational research, 87(6), 1042–1081.

Biwer, F., de Bruin, A., & Persky, A. (2022). Study smart - impact of a learning strategy training on students’ study behavior and academic performance. Advances in health sciences education: theory and practice. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-022-10149-z.

Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society, 2(59–68).

Blasiman, R. N. (2017). Distributed Concept Reviews improve exam performance. Teaching of Psychology, 44(1), 46–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628316677646.

Blasiman, R. N., Dunlosky, J., & Rawson, K. A. (2017). The what, how much, and when of study strategies: Comparing intended versus actual study behaviour. Memory (Hove, England), 25(6), 784–792.

Breckwoldt, J., Ludwig, J. R., Plener, J., Schroder, T., Gruber, H., & Peters, H. (2016). Differences in procedural knowledge after a “spaced” and a “massed” version of an intensive course in emergency medicine, investigating a very short spacing interval. BMC medical education, 16, 249. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0770-6.

Brown-Kramer, C. R. (2021). Improving students’ Study Habits and Course Performance with a “Learning how to Learn” assignment. Teaching of Psychology, 48(1), 48–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628320959926. Article 0098628320959926.

Browne, C. J. (2019). Assessing the engagement rates and satisfaction levels of various clinical health science student sub-groups using supplementary eLearning resources in an introductory anatomy and physiology unit. Health Education (0965–4283), 119(1), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/HE-04-2018-0020.

Bruckel, J., Carballo, V., Kalibatas, O., Soule, M., Wynne, K. E., Ryan, M. P., Shaw, T., & Co, J. P. T. (2016). Use of spaced education to deliver a curriculum in quality, safety and value for postgraduate medical trainees: Trainee satisfaction and knowledge [Article]. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 92(1085), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133446.

Burdo, J., & O’Dwyer, L. (2015). The effectiveness of concept mapping and retrieval practice as learning strategies in an undergraduate physiology course [Article]. Advances in Physiology Education, 39(1), 335–340. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00041.2015.

Butler, A. C., Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, I. I. I., H. L (2007). The effect of type and timing of feedback on learning from multiple-choice tests. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 13(4), 273.

Cadaret, C. N., & Yates, D. T. (2018). Retrieval practice in the form of online homework improved information retention more when spaced 5 days rather than 1 day after class in two physiology courses. Advances in Physiology Education, 42(2), 305–310. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00104.2017.

Carpenter, S., Lund, T., Coffman, C., Armstrong, P., Lamm, M., & Reason, R. (2016). A Classroom Study on the relationship between Student Achievement and Retrieval-Enhanced learning [Article]. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 353–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9311-9.

Carpenter, S. K., Rahman, S., & Perkins, K. (2018). The effects of prequestions on classroom learning [Article]. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 24(1), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000145.

Cecilio-Fernandes, D., Aalders, W. S., de Vries, J., & Tio, R. A. (2018). The Impact of Massed and Spaced-Out Curriculum in Oncology Knowledge Acquisition [Article]. Journal of Cancer Education, 33(4), 922–925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-017-1190-y.

Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 354.

Cepeda, N. J., Vul, E., Rohrer, D., Wixted, J. T., & Pashler, H. (2008). Spacing effects in learning: A temporal ridgeline of optimal retention. Psychological science, 19(11), 1095–1102.

Chang, D., Kenel-Pierre, S., Basa, J., Schwartzman, A., Dresner, L., Alfonso, A. E., & Sugiyama, G. (2014). Study habits centered on completing review questions result in quantitatively higher American Board of surgery In-Training exam scores. Journal of surgical education, 71(6), e127–e131.

Chen, F. M., Bauchner, H., & Burstin, H. (2004). A call for outcomes research in medical education. Academic medicine, 79(10), 955–960.

Cook, D. A., & Reed, D. A. (2015). Appraising the quality of medical education research methods: The medical education research study quality instrument and the Newcastle–Ottawa scale-education. Academic medicine, 90(8), 1067–1076.

Cook, D. A., Hamstra, S. J., Brydges, R., Zendejas, B., Szostek, J. H., Wang, A. T., Erwin, P. J., & Hatala, R. (2013). Comparative effectiveness of instructional design features in simulation-based education: Systematic review and meta-analysis [Article]. Medical teacher, 35(1), e844–e898. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.714886.

Dobson, J. L. (2011). Effect of selected “Desirable Difficulty” learning strategies on the Retention of Physiology Information. Advances in Physiology Education, 35(4), 378–383. http://ezproxy.acu.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true &db=eric&AN=EJ956464&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Dobson, J. L. (2012). Effect of Uniform versus Expanding Retrieval Practice on the Recall of Physiology Information. Advances in Physiology Education, 36(1), 6–12. http://ezproxy.acu.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true &db=eric&AN=EJ968834&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Dobson, J. L. (2013). Retrieval Practice is an efficient method of enhancing the Retention of anatomy and physiology information. Advances in Physiology Education, 37(2), 184–191. http://ezproxy.acu.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true &db=eric&AN=EJ1013528&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Dobson, J., & Linderholm, T. (2015a). Self-testing promotes superior retention of anatomy and physiology information [Article]. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 20(1), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-014-9514-8.

Dobson, J. L., & Linderholm, T. (2015b). The effect of selected “desirable difficulties” on the ability to recall anatomy information. Anatomical Sciences Education, 8(5), 395–403. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1489.

Dobson, J. L., Linderholm, T., & Yarbrough, M. B. (2015). Self-testing produces superior recall of both familiar and unfamiliar muscle information [Article]. Advances in Physiology Education, 39(1), 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00052.2015.

Dobson, J. L., Perez, J., & Linderholm, T. (2017). Distributed retrieval practice promotes superior recall of anatomy information. Anatomical Sciences Education, 10(4), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1668.

Dobson, J., Linderholm, T., & Perez, J. (2018). Retrieval practice enhances the ability to evaluate complex physiology information [Article]. Medical education, 52(5), 513–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13503.

Dobson, J. L., Linderholm, T., & Stroud, L. (2019). Retrieval practice and judgements of learning enhance transfer of physiology information [journal article]. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 24(3), 525–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-019-09881-w.

Dunlosky, J., & Rawson, K. A. (2012). Overconfidence produces underachievement: Inaccurate self evaluations undermine students’ learning and retention. Learning and Instruction, 22(4), 271–280.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4–58.

Ernst, K. D., Cline, W. L., Dannaway, D. C., Davis, E. M., Anderson, M. P., Atchley, C. B., & Thompson, B. M. (2014). Weekly and Consecutive Day neonatal intubation training: Comparable on a Pediatrics Clerkship. Academic medicine, 89(3), 505–510. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000150.

Fendos, J. (2020). Anatomy terminology performance is improved by combining Jigsaws, Retrieval Practice, and cumulative quizzing [Article]. Anatomical Sciences Education. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.2018.

Francis, A. P., Wieth, M. B., Zabel, K. L., & Carr, T. H. (2020). A Classroom Study on the role of prior knowledge and Retrieval Tool in the testing effect [Article]. Psychology Learning and Teaching, 19(3), 258–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725720924872.

Gerbier, E., Toppino, T. C., & Koenig, O. (2015). Optimising retention through multiple study opportunities over days: The benefit of an expanding schedule of repetitions [Article]. Memory (Hove, England), 23(6), 943–954. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2014.944916.

Ghanbari, S., Haghani, F., & Akbarfahimi, M. (2019). Practical points for brain-friendly medical and health sciences teaching [Article]. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 8(1), https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_135_19.

Glass, A. L., Ingate, M., & Sinha, N. (2013). The Effect of a final exam on Long-Term Retention. Journal of General Psychology, 140(3), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2013.797379.

Gopalan, C., Fentem, A., & Rever, A. L. (2020). The refinement of flipped teaching implementation to Include Retrieval Practice. Advances in Physiology Education, 44(2), 131–137. http://ezproxy.acu.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true &db=eric&AN=EJ1252271&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Gurung, R. A. R., & Burns, K. (2019). Putting evidence-based claims to the test: A multi‐site classroom study of retrieval practice and spaced practice [Article]. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 33(5), 732–743. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3507.

Head, M. L., Holman, L., Lanfear, R., Kahn, A. T., & Jennions, M. D. (2015). The extent and consequences of p-hacking in science. PLoS biology, 13(3), e1002106.

Hernick, M. (2015). Test-enhanced learning in an Immunology and Infectious Disease Medicinal Chemistry/Pharmacology course [Article]. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 79(7), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe79797.

Higham, P. A., Zengel, B., Bartlett, L. K., & Hadwin, J. A. (2022). The benefits of Successive relearning on multiple learning outcomes [Article]. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(5), 928–944. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000693.

Hinze, S. R., & Rapp, D. N. (2014). Retrieval (sometimes) enhances learning: Performance pressure reduces the benefits of retrieval practice. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 28(4), 597–606.

Inclan, M. L., & Meyer, B. D. (2020). Pre-doctoral special healthcare needs education: Lost in a crowded curriculum. Journal of Dental Education, 84(9), 1011–1015.

Iwamoto, D. H., Hargis, J., Taitano, E. J., & Vuong, K. (2017). Analyzing the efficacy of the testing effect using Kahoot™ on student performance. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 18(2), 80–93. ://WOS:000414268600007.

Janes, J. L., Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., & Jasnow, A. (2020). Successive relearning improves performance on a high-stakes exam in a difficult biopsychology course [Article]. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34(5), 1118–1132. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3699.

Karpicke, J. D. (2009). Metacognitive Control and Strategy Selection: Deciding to Practice Retrieval during Learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 138(4), 469–486. http://ezproxy.acu.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true &db=eric&AN=EJ860923&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Karpicke, J. D., & Blunt, J. R. (2011). Retrieval Practice produces more learning than Elaborative studying with Concept Mapping [Article]. Science, 331(6018), 772–775. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1199327.

Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L. 3rd (2007). Expanding retrieval practice promotes short-term retention, but equally spaced retrieval enhances long-term retention. Journal of experimental psychology Learning memory and cognition, 33(4), 704–719. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.33.4.704.

Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L. 3rd (2010). Is expanding retrieval a superior method for learning text materials? Memory & Cognition, 38(1), 116–124. https://doi.org/10.3758/MC.38.1.116.

Kerdijk, W., Cohen-Schotanus, J., Mulder, B. F., Muntinghe, F. L. H., & Tio, R. A. (2015). Cumulative versus end-of-course assessment: Effects on self-study time and test performance. Medical education, 49(7), 709–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12756.

Keus, K., Grunwald, J., & Haave, N. (2019). A method to the Midterms: The impact of a second midterm on students’ learning outcomes [Article]. Bioscene, 45(1), 3–8. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true &AuthType=shib&db=eue&AN=140819751&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5501413.

Kliegl, O., Bjork, R. A., & Bäuml, K. H. T. (2019). Feedback at Test can reverse the Retrieval-Effort Effect. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 1863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01863.

Kumar, A., Sarkar, M., Davis, E., Morphet, J., Maloney, S., Ilic, D., & Palermo, C. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning in health professional education: A mixed methods study protocol. BMC medical education, 21(1), 1–7.

Küpper-Tetzel, C. E., Kapler, I. V., & Wiseheart, M. (2014). Contracting, equal, and expanding learning schedules: The optimal distribution of learning sessions depends on retention interval. Memory & Cognition, 42(5), 729–741.

LaDisa, A. G., & Biesboer, A. (2017). Incorporation of practice testing to improve knowledge acquisition in a pharmacotherapy course [Article]. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching & Learning, 9(4), 660–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2017.03.002.

Lawson, T. J. (2022). Effects of Cued-Recall Versus Recognition Retrieval practice on beginning College Students’ exam performance [Article]. College Teaching, 70(2), 181–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2021.1910124.

Linderholm, T., Dobson, J., & Yarbrough, M. B. (2016). The benefit of self-testing and interleaving for synthesizing concepts across multiple physiology texts. Advances in Physiology Education, 40(3), 329–334. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00157.2015.

Little, J. L., & Bjork, E. L. (2016). Multiple-choice pretesting potentiates learning of related information. Memory & Cognition, 44(7), 1085–1101.

Loftus, G. R. (1985). Evaluating forgetting curves. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition, 11(2), 397.

Logan, N. S., Hatch, R. A., & Logan, H. L. (1975). Massed vs. distributed practice in learning dental psycho-motor skills. Journal of Dental Education, 39(2), 87–91. http://ezproxy.acu.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/loginaspx?direct=true&db=mdc&AN=1054368&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

McDaniel, M. A., Howard, D. C., & Einstein, G. O. (2009). The read-recite-review study strategy: Effective and portable. Psychological science, 20(4), 516–522.

Messineo, L., Gentile, M., & Allegra, M. (2015). Test-enhanced learning: Analysis of an experience with undergraduate nursing students. BMC medical education, 15, Article 182. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0464-5.

Miller, T. M., & Srimaneerungroj, N. (2022). Testing, testing: In-Class testing facilitates transfer on cumulative exams [Article]. Journal of Cognitive Education & Psychology, 21(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1891/JCEP-2021-0018.

Miller, A., & Young-Jones, A. D. (2012). Academic integrity: Online classes compared to face-to-face classes. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 39(3).

Moore, F. G. A., & Chalk, C. (2012). Improving the neurological exam skills of medical students. The Canadian journal of neurological sciences Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques, 39(1), 83–86. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0317167100012749.

Naciri, A., Radid, M., Kharbach, A., & Chemsi, G. (2021). E-learning in health professions education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Journal of educational evaluation for health professions, 18.

Nevid, J. S., Pyun, Y. S., & Cheney, B. (2016). Retention of text material under Cued and Uncued Recall and Open and Closed Book Conditions [Article]. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning, 10(2), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2016.100210.

Oermann, M. H., Krusmark, M. A., Kardong-Edgren, S., Gluck, K. A., & Jastrzembski, T. S. (2022a). Retention in Spaced Practice of CPR skills in nursing students. MEDSURG Nursing, 31(5), 285–294. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true &AuthType=shib&db=ccm&AN=159859834&site=ehost-live&scope=site&custid=s5501413.

Oermann, M. H., Krusmark, M. A., Kardong-Edgren, S., Jastrzembski, T. S., & Gluck, K. A. (2022b). Personalized training schedules for Retention and Sustainment of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Skills. Simulation in Healthcare-Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 17(1), E59–E67. https://doi.org/10.1097/sih.0000000000000559.

Opre, D., Serban, C., Vescan, A., & Iucu, R. (2022). Supporting students’ active learning with a computer based tool. Active Learning in Higher Education, 14697874221100465. https://doi.org/10.1177/14697874221100465.

Osterhage, J. L., Usher, E. L., Douin, T. A., & Bailey, W. M. (2019). Opportunities for self-evaluation increase student calibration in an Introductory Biology Course. CBE life sciences education, 18(2), ar16. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-10-0202.

Palmen, L. N., Vorstenbosch, M. A. T. M., Tanck, E., & Kooloos, J. G. M. (2015). What is more effective: A daily or a weekly formative test? Perspectives on medical education, 4(2), 73–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-015-0178-8.

Palmer, S., Youn, C., & Persky, A. M. (2019). Comparison of rewatching Class Recordings versus Retrieval Practice as Post-Lecture Learning strategies [Article]. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 83(9), 1958–1965. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7217.

Pannucci, C. J., & Wilkins, E. G. (2010). Identifying and avoiding bias in research. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 126(2), 619.

Persky, A. M., & Hudson, S. L. (2016). A snapshot of student study strategies across a professional pharmacy curriculum: Are students using evidence-based practice? [Article]. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 8(2), 141–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2015.12.010.

Phelps, R. P. (2012). The effect of testing on student achievement, 1910–2010. International Journal of Testing, 12(1), 21–43.

Piza, F., Kesselheim, J. C., Perzhinsky, J., Drowos, J., Gillis, R., Moscovici, K., Danciu, T. E., Kosowska, A., & Gooding, H. (2019). Awareness and usage of evidence-based learning strategies among health professions students and faculty. Medical teacher, 41(12), 1411–1418.

Platt, C. A., Amber, N., & Yu, N. (2014). Virtually the same?: Student perceptions of the equivalence of online classes to face-to-face classes. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 10(3), 489.

Poorthuis, A. M. G., & van Dijk, A. (2021). Online Study-Aids to Stimulate Effective Learning in an Undergraduate Psychological Assessment Course. Psychology Learning and Teaching-Plat, Article 1475725720964761. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725720964761.

Prystowsky, J. B., & Bordage, G. (2001). An outcomes research perspective on medical education: The predominance of trainee assessment and satisfaction. Medical education, 35(4), 331–336.

Racsmány, M., Szőllősi, Á., & Marián, M. (2020). Reversing the testing effect by feedback is a matter of performance criterion at practice. Memory & Cognition, 48(7), 1161–1170. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-020-01041-5.

Reed, D. A., Cook, D. A., Beckman, T. J., Levine, R. B., Kern, D. E., & Wright, S. M. (2007). Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. Jama, 298(9), 1002–1009.

Richland, L. E., Kornell, N., & Kao, L. S. (2009). The pretesting effect: Do unsuccessful retrieval attempts enhance learning? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 15(3), 243.

Rohrer, D. (2015). Student instruction should be distributed over Long Time Periods. Educational Psychology Review, 27(4), 635–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9332-4.

Rowland, C. A. (2014). The effect of testing versus restudy on retention: A meta-analytic review of the testing effect. Psychological Bulletin, 140(6), 1432.

Schmidmaier, R., Ebersbach, R., Schiller, M., Hege, I., Holzer, M., & Fischer, M. R. (2011). Using electronic flashcards to promote learning in medical students: Retesting versus restudying. Medical education, 45(11), 1101–1110.

Schmutz, A. M., Jenkins, L. S., Coetzee, F., Conradie, H., Irlam, J., Joubert, E. M., Matthews, D., & Schalkwyk, S. C. v (2021). Re-imagining health professions education in the coronavirus disease 2019 era: Perspectives from South Africa. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 13(1), 2948.

Schneider, A., Kuhl, M., & Kuhl, S. J. (2019). Utilizing research findings in medical education: The testing effect within an flipped/inverted biochemistry classroom. Medical teacher, 41(11), 1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2019.1628195.

Sennhenn-Kirchner, S., Goerlich, Y., Kirchner, B., Notbohm, M., Schiekirka, S., Simmenroth, A., & Raupach, T. (2018). The effect of repeated testing vs repeated practice on skills learning in undergraduate dental education. European Journal of Dental Education, 22(1), E42–E47. https://doi.org/10.1111/eje.12254.

Shobe, E. (2022). Achieving Testing Effects in an authentic College Classroom [Article]. Teaching of Psychology, 49(2), 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/00986283211015669.

Son, L. K., & Metcalfe, J. (2000). Metacognitive and control strategies in study-time allocation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition, 26(1), 204.

Terenyi, J., Anksorus, H., & Persky, A. M. (2018). Impact of spacing of practice on learning brand name and generic drugs [Article]. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 82(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe6179.

Terenyi, J., Anksorus, H., & Persky, A. M. (2019). Optimizing the spacing of Retrieval Practice to Improve Pharmacy Students’ learning of drug names [Article]. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 83(6), 1213–1219. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7029.

Timmer, M. C. J., Steendijk, P., Arend, S. M., & Versteeg, M. (2020). Making a lecture Stick: The Effect of Spaced instruction on Knowledge Retention in Medical Education. Medical science educator, 30(3), 1211–1219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-00995-0.

Trumbo, M. C., Leiting, K. A., McDaniel, M. A., & Hodge, G. K. (2016). Effects of reinforcement on test-enhanced learning in a large, diverse introductory College psychology course. Journal of Experimental Psychology-Applied, 22(2), 148–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000082.

Veltre, M. T., Cho, K. W., & Neely, J. H. (2015). Transfer-appropriate processing in the testing effect [Article]. Memory (Hove, England), 23(8), 1229–1237. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2014.970196.

Versteeg, M., Hendriks, R. A., Thomas, A., Ommering, B. W. C., & Steendijk, P. (2020). Conceptualising spaced learning in health professions education: A scoping review. Medical education, 54(3), 205–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14025.

Wong, D. (2022). Active learning in osteopathic education: Evaluation of think-pair-share in an undergraduate pathology unit. International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, 43, 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijosm.2021.12.001.

Xu, J. (2013). Why do students have difficulties completing homework? The need for homework management. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 1(1), 98–105.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Emma Trumble wrote the main manuscript text and all authors contributed to and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

There are no competing interests directly or indirectly related to this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Trumble, E., Lodge, J., Mandrusiak, A. et al. Systematic review of distributed practice and retrieval practice in health professions education. Adv in Health Sci Educ 29, 689–714 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-023-10274-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-023-10274-3