Abstract

There is increasing interest in the use of ethnography as a qualitative research approach to explore, in depth, issues of culture in health professions education (HPE). Our specific focus in this article is incorporating the digital into ethnography. Digital technologies are pervasively and increasingly shaping the way we interact, behave, think, and communicate as health professions educators and learners. Understanding the contemporary culture(s) of HPE thus means paying attention to what goes on in digital spaces. In this paper, we critically consider some of the potential issues when the field of ethnography exists outside the space time continuum, including the need to engage with theory in research about technology and digital spaces in HPE. After a very brief review of the few HPE studies that have used digital ethnography, we scrutinize what can be gained when ethnography encompasses the digital world, particularly in relation to untangling sociomaterial aspects of HPE. We chart the shifts inherent in conducting ethnographic research within the digital landscape, specifically those related to research field, the role of the researcher and ethical issues. We then use two examples to illustrate possible HPE research questions and potential strategies for using digital ethnography to answer those questions: using digital tools in the conduct of an ethnographic study and how to conduct an ethnography of a digital space. We conclude that acknowledging the pervasiveness of technologies in the design, delivery and experiences of HPE opens up new research questions which can be addressed by embracing the digital in ethnography.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“All forms of interaction are ethnographically valid, not just the face to face” (Hine, 2000, p.65).

All of our lives, to some degree, take place in digital spaces. We tweet, we blog, we use Facebook, we text, we WhatsApp, we are “tagged” in something posted by a third party, we are part of online communities. At work, we use email, have remote meetings, upload tasks onto the digital learning management system, use online systems to share data, and so on. Health professions education is increasingly constituted through digitized practices where social interactions and cultural meaning-making processes occur in virtual and online spaces, or in a combination of online and face-to-face spaces (Hine, 2000; Boellstorff et al., 2012; Gatson, 2011).

Digital technology shapes the way we interact, behave, think, and communicate and, in doing so, it has changed the roles of space, place and time in human and material interactions. Space is no longer defined as the congregation of people in any specific place but rather is defined beyond the physical. In other words, space is digitally mediated as well as direct contact with other people (Murthy, 2008). Digital technologies have thus extended the nature of human interactions to encompass “distanced” and dispersed communication and different types of proximity in ways that no other technology has done to date (e.g., Murthy, 2008). Time is fluid and flexible, with asynchronous options for engaging online meaning people participate when it works for them, rather than during mandatory, prescribed periods (Burcks et al., 2019).

If social interactions are no longer solely co-located in time and space, we must extend ethnographic study to settings where interactions are technologically mediated, not just face-to-face (e.g., Bengtsson, 2014; Hine, 2015). Ethnographers who rely principally on face-to-face interviewing and in-person observation are now unlikely to obtain a sufficiently rich picture of their informants’ lives because it is increasingly difficult to separate the online from the embodied, and the digitally-mediated aspects of life now are not amenable to (traditional) observation (Beaulieu, 2010; Czarniawska, 2008).

This ontological shift necessitates thinking differently about ethnographic practices, including the questions that can be addressed, the methods that can be used, and the ethical challenges to consider. What remains the same and what is different when conducting an ethnography of a digital space, compared to “analogue”, or traditional ethnography (Boellstorff et al., 2012; Seligman & Estes, 2020)?

Before discussing this further, it is useful to explain what we mean by digital ethnography. Different authors use different terms to describe their approaches to ethnographic research on digital culture and practices (e.g., ‘digital ethnography’ (Murthy, 2008), ‘virtual ethnography’ (Hine, 2000), ‘cyberethnography’ (Robinson & Schulz, 2009), ‘netnography’ (Kozinets, 2010)) and even different definitions within each of these labels (for example, there are many subtly different definitions of digital ethnography (Hines, 2000, 2008, 2015; Murthy, 2008; Pink et al., 2015)). Common to all these definitions, and the position we take in this paper, is that digital ethnography is research ‘on online practices and communications, and on offline practices shaped by digitalisation’ (Varis, 2016, p.57), and involves human beings studying other human beings (rather than software collecting data: see Kozinets et al., 2018).

Our experience and knowledge of the literature suggests that broadly speaking, the aims of ethnography and digital ethnography are the same: to provide detailed, in-depth descriptions of everyday life and practices (Hammersley & Atkinson, 2007; Hoey, 2014). The practicalities, use of theory and the need for reflexivity are also unchanged. However, the role of the researcher, the notions of field/place and data collection tools differ across traditional and digital ethnography (e.g., da Costa & Condie, 2018; Markham, 2005). Additionally, digital ethnography opens up both new ethical considerations and new opportunities, specifically to examine the complex ways in which culture—the everyday practices, experiences, and understandings of persons interacting digitally—shapes and is shaped by the technological platforms where it occurs (Hine, 2000, 2008).

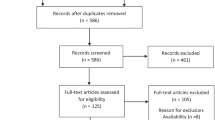

Despite the fact that bringing the digital into ethnography opens up new vistas of health professions education research (HPER) possibilities, our field has been slow to embrace digital ethnography. A focused search of two mainstream databases identified only six empirical studies which could be considered broadly related to medical education or training (not patient care, or the organisation of care) and which included analysis of some form of digital data (see Box 1). In this era of physical distancing, in which so much of the work of HPE is accomplished online, it is time to foreground digital ethnography.

To address this gap and extend understanding of digital ethnography, therefore, we discuss each of three key areas—the use of theory, “new” ethical considerations and digital ethnography practices. We then suggest directions for the development of digital ethnographic studies and best practices in the field of HPE via two detailed examples and other suggestions of how this approach could extend knowledge and understanding in health professions education.

Theory in digital ethnography

Oversimplified, atheoretical perspectives on the role of technology in research on learning have long characterized the field. Several decades ago, Lave and Wenger noted, “in general, social scientists who concern themselves with learning treat technology as a given and are not analytic about its interrelations with other aspects of a community of practice” (1991, p. 101).

Sociomaterial theoretical perspectives, based on the related concepts of situated learning (Lave & Wenger, 1991), distributed cognition (Hutchins, 1995), and activity theory (Engeström, 1999), offer a robust theoretical starting point for making sense of online activities in the realm of HPE. Now recognized as an important perspective for understanding the active role of digital technologies (MacLeod et al., 2015, 2019), sociomaterial perspectives allow for the theorizing of the entanglement of both social (human) and material (digital) elements—in other words, a sociomaterial assemblage. This, in turn, allows a researcher to explore the social complexities of a digital environment while acknowledging the foundational materiality shaping it.

Orlikowski and Scott (2008) note that the distinction between social and material, or human and technology, is “analytical only, and done with the recognition that these entities necessarily entail each other in practice” (p. 456). Given that technology, the digital environment, and contemporary learning and working practices are inextricably linked, any effort to theorize online HPE activities would be enriched by deliberately attuning to such intra-actions. Well-conceptualised digital ethnographic work should illuminate the ways in which technological elements derive meaning through social agency, and vice-versa. For example, Wesch (2012, p. 101) states that different platforms “create different architectures for participation” and “every feature shapes the possibilities for sociality.” People engage with multiple social media platforms for different purposes, so one sees different content, interactions, and levels of impression management in work emails, WhatsApp, on public platforms like Twitter and more private platforms that may require “friending” someone to see their content (Facebook, Instagram). Different interactions may take place in relatively stable and bounded socio-technical contexts (e.g., discussion forums), compared to more “volatile environments” (Airoldi, 2018 p.662) such as Twitter’s trending topics. Indeed, “specific practices and ways of being human are as likely to differ between online and off, between one form of online activity and another, as between physically located cultures” (Wilson & Peterson, 2002, p 450).

Ethical considerations

As the amount of human activity on digital media has increased, so too have ethical concerns about doing research within digital spaces. How can a researcher obtain informed consent in digital spaces given the flow of information and flow of users, not all of whom read all messages (Barbosa & Milan, 2019)? What issues need to be negotiated when it comes to friending participants for the purposes of participant observation (Robards, 2013)? These and many other questions have led authors to propose that embracing digital spaces for research purposes challenges “existing conventions of ethics” and requires new ways of approaching such concerns (Markham, 2005; Thompson et al., 2020).

For example, there are different schools of thought about what is public and what is private in the digital sphere (West, 2017). Some researchers posit that messages posted in blogs, chat rooms and any other accessible online forums should be treated as in the public domain and thus do not require informed consent to access. Others argue that just because information is accessible online does not mean participants do not consider it as private or available only to a restricted audience, and therefore informed consent should be required. The concept of contextual integrity (Nissenbaum, 2004) helps here. Briefly, contextual integrity assumes that privacy is related to, and modulated by, the flow of information based on norms that are context-dependant. What context is remains fuzzy, but contextual integrity is based on the notion that individual platforms (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, a workplace) constitute cultural spaces with different practices around privacy and anonymity (Ozkula, 2020).

Second, online practices bring privacy risks (Buglass et al., 2017; Politou et al., 2018). Incidences of “zoom bombings” (e.g., Ling et al., 2021) where people find their way into digital spaces that were intended to be private, including classrooms and PhD defences, are a significant challenge. The increasing sophistication of web search engines mean that quotes that might appear in ethnographic texts can be traced back to the original postings in the public forums, increasing the potential of identification. Researchers may need to paraphrase the participants’ quotations, paying careful attention to changing details of the data, and the social media platform, to assure confidentiality and privacy (e.g., Thompson et al., 2020).

On the other hand, digital communication increases the potential to access, recruit, and engage individuals in one’s research (Caliandro, 2018). Where engagement is purely digital, there are no geographic or social barriers to participation—so hard-to-reach groups may be more accessible (e.g., Morison et al., 2015). Participants may also be more likely to allow a researcher access to sensitive topics where they are already engaging in these discussions online (e.g., the content of a trauma support forum’s online discussion) rather than recalling difficult experiences in a traditional interview. Moreover, social media, messaging apps, and digital tools allow researchers to engage informants/participants in the research process and allow for collaborative ethnography to emerge more easily (Collins & Durington, 2014). Finally, when a data collection period is over, people may keep in touch, providing the researcher with updates via, for example, WhatsApp. These updates can enable follow-up and longitudinal data collection that might not have been possible using more traditional ethnography methods. For example, Robards and Lincoln (2017) in a study of Facebook timelines, or traces, remained friends with their informants after the main data collection period. This allowed them to go back into profiles, revisit particular posts, and clarify events during data analysis.

We also direct readers to Christensen, Larsen and Wind’s (2018) comprehensive guide to the literature on ethical challenges when working with different types of digital data (e.g., social media, online communities, Twitter).

The practices of digital ethnography

The similarities and differences between analogue and digital ethnography are summarised in Table 1. (Those wishing a deeper dive into the basic tenets of ethnography will find these references helpful [Reeves et al., 2013; MacLeod, 2016; Bressers et al., 2020]). We discuss the field site and the role of the researcher in more detail here.

The field site

The concepts of space and a field site are reconceptualised in digital ethnography. The field site is not a single, discrete geographical place but is a “stage on which the social processes under study take place” (Burrell, 2009). This stage may be digital, or it may be part of broader configurations, straddling digital and face-to-face interactions (see Box 2). Examining the entanglement of online and “offline” interactions by “following the thing” (Marcus, 1995) allows fieldworkers to shed new light on the nuanced ways that people engage with different media, how people combine different modes of communication, and the potentially conflicting information that each may yield.

As always in ethnography, digital ethnographers must determine how to apply boundaries in virtual and other spaces in which they will do their work, but these boundaries are not determined by a physical space. Researchers may decide in advance only to engage with certain content and/or groups, limit their sample size or research question, and provide practical and theoretical reasons for such decisions (Hine, 2015; Markham, 2005). They may also decide to apply boundaries by focusing only on a particular digital platform (see earlier).

The role of the researcher

Like “traditional” fieldwork, digital ethnographic methods draw on the researcher’s experience as an observer to gain understanding of (digital) culture and communicate the meaning system and practices of its members (Kozinets, 2010). In digital ethnography participation can vary from being identified as a researcher and actively engaging with the participant(s) to covert presence—that is, remaining invisible to the people whose activities are being observed (e.g., Barbosa & Milan, 2019). This lack of visibility—impossible in traditional embodied ethnography where the research is present in space and time—may be an artifact of the challenges of maintaining presence in digital spaces. What we mean by this is that the researcher may disclose their presence, inform participants about the research, and consistently and overtly interact with informants (Murthy, 2008). However, the speed and volume of online activity can mean the researcher fades into the background—participants are often only aware of the people with whom they are directly and actively interacting. On the other hand, “invisibility” may be a conscious decision on the part of the digital ethnographer. This raises the notion of ‘lurking’ (Hine, 2000)—mining for data without interaction, or acting as a participant without researcher transparency. Views on the legitimacy of lurking as a digital ethnographic endeavour vary, from the positive (an opportunity to collect data on unfiltered behaviour), to the wary (can lurking be regarded as ethnographic observation given it is not participatory?) (Varis, 2016), to caution that purely observing interaction increases the risk of misunderstanding the observed (Gold, 1958; Hines, 2000), to considering this unethical research behaviour (e.g., (Doring, 2002). There are also nuances to consider. For example, is it acceptable for a researcher to use covert approaches for a brief period during the planning and early stages of a project, to orient themselves with the digital presence of communities, forms of practice, language, and so on (Hine, 2008)? We cannot offer definitive guidance but raise these issues for consideration.

Researchers need to consider what they bring to the field, and to analysis, in terms of formal, reflexive practices including their personal and social assumptions but also their digital and media persona, and how these may shape the relationship between researcher and participants (Gershon, 2010; Tagg et al., 2017; see also Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992). Hine (2000) cautions that even the screen name one chooses is an important consideration because it might affect participant engagement. It is also important for researchers to consider their own digital footprint (i.e.,—what information is findable with a Google search), as this may lead to stereotypisation of the researcher, initial distrust or suspicion (Numerato, 2016).

Applications and opportunities

Given the pervasiveness of digital technologies in the design, delivery and experiences of health professions education, it follows logically that attuning to the digital as an artefact of, and a substrate for, culture will open up new research inquiries and extend knowledge in the field. To illustrate this, we provide two in-depth examples of possible research questions and potential strategies for using digital ethnography to answer those questions. One example looks at how to conduct an ethnography of a digital space and draws on sociomaterial theory. The second example looks at using digital tools in the conduct of an ethnographic study and draws on a theory of social interaction which has been used previously in both traditional and digital ethnographic studies (Kerrigan & Hart, 2016; Leigh et al., 2021) (Boxes 3 and 4).

These examples are illustrative. Those wishing to find out more about different approaches to digital ethnography may wish to delve into the empirical references identified in our search and reported in Box 2 (Chretien et al., 2015; Henninger, 2020; Macleod & Fournier, 2017; Meeuwissen et al., 2021; Pérez-Escoda et al., 2020; Wieringa et al., 2018). We also suggest some outstanding research questions and topics which could be explored using various different digital ethnographic practices in Table 2. These suggestions are by no means exhaustive. Rather they reflect our own interests and observations and should be regarded as a springboard to help readers consider diverse ways in which digital ethnography may add knowledge and richness in our field. They also illustrate how the many different approaches encompassed within the broad heading of digital ethnography allow researchers to tailor a methodology according to the research problem.

Conclusion

Digital ethnography has much to offer in untangling the social and material complexities of health professions education. Bringing the digital into ethnography opens up new research vistas, and allows us to identify and answer questions which are emerge as our practices and interactions become increasingly digitalized. As Hallett and Barber (2014) state, ‘it is no longer imaginable to conduct ethnography without considering online spaces’ (p.307).

References

Airoldi, M. (2018). Ethnography and the digital fields of social media. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21(6), 661–673.

Androutsopoulos J. (2008). Potentials and Limitations of Discourse-Centred Online Ethnography. Language@Internet, 5. https://www.languageatinternet.org/articles/2008/1610 (Accessed 24 Nov 2021).

Arenas R. (2019). Virtually healthy: Using virtual ethnography to survey healthcare seeking practices of transgender individuals online. Dissertation UNLV https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations/3564/ (Accessed 24 Nov 2021).

Ball, S. (2016). Following policy: Networks, network ethnography and education policy mobilities. Journal of Education Policy, 31(5), 549–566.

Barbosa, S., & Milan, S. (2019). Do not harm in private chat apps: Ethical issues for research on and with whatsapp. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 14, 49–65.

Beaulieu, A. (2010). Research note: From co-location to co-presence: Shifts in the use of ethnography for the study of knowledge. Social Studies of Science, 40(3), 453–470.

Bengtsson, S. (2014). Faraway, so close! Proximity and distance in ethnography online. Media, Culture & Society, 36(6), 862–877.

Berthod, O., Grothe-Hammer, M., & Sydow, J. (2017). Network ethnography: A mixed-method approach for the study of practices in interorganizational settings. Organizational Research Methods, 20(2), 299–323.

Boellstorff, T., Nardi, B., Pearce, C., & Taylor, T. L. (2012). Ethnography and Virtual Worlds. Princeton University Press.

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1992). An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Polity Press.

Bressers, G., Brydges, M., & Paradis, E. (2020). Ethnography in health professions education: Slowing down and thinking deeply. Medical Education, 54(3), 225–233.

Buglass, S. L., Binder, J. F., Betts, L. R., & Underwood, J. D. M. (2017). Motivators of online vulnerability: The impact of social network site use and FOMO. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 248–255.

Burcks S.M., Siegel M.A., Murakami C.D., & Marra R.M. (2019) Sociomaterial Relations in Asynchronous Learning Environments. In: Milne C., Scantlebury K. (eds) Material Practice and Materiality: Too Long Ignored in Science Education. Cultural Studies of Science Education, vol 18. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01974-7_12

Burrell, J. (2009). The field site as a network: A strategy for locating ethnographic research. Field Methods, 21(2), 181–199.

Caliandro, A. (2018). Digital methods for ethnography: Analytical concepts for ethnographers exploring social media environments. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 47(5), 551–578.

Chretien, K. C., Tuck, M. G., Simon, M., Singh, L. O., & Kind, T. (2015). A digital ethnography of medical students who use twitter for professional development. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(11), 1673–1680.

Christensen L.L., Larsen M.C., & Wind S.T. (2018). Ethical challenges in digital research: A guide to discuss ethical issues in digital research. (1. edn). https://dighumlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Ethical_challenges_in_digital-research.pdf (Accessed 24 Nov 2021).

Collins, S. G., & Durington, M. S. (2014). Networked Anthropology: A Primer for Ethnographers (1st ed.). Routledge.

Cunliffe, A. L. (2010). Retelling tales of the field: In search of organizational ethnography 20 years on. Organizational Research Methods, 13(2), 224–239.

Czarniawska, B. (2008). Organizing: How to study it and how to write about it. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management, 3(1), 4–20.

Da Costa, C. M., & Condie, J. (2018). Doing research in and on the Digital. In C. Costa & J. Condie (Eds.), Doing Research In and On the Digital: Research Methods across Fields of Inquiry. Routledge.

Doring, N. (2002). Studying online love and cyber romance. In: B. Batinic U.D. Reips, & M. Bosnjak (Eds) Online social sciences. Hogrefe and Huber, Seattle, WA, (pp. 333–356).

Eaton, P. W., & Pasquini, L. A. (2020). Networked practices in higher education: A netnography of the #AcAdv chat community. The Internet and Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100723(accessed24Nov2021)

Engeström, Y., et al. (1999). Innovative learning in work teams: Analysing cycles of knowledge creation in practice. In Y. Engstrom (Ed.), Perspectives on Activity Theory (pp. 377–406). Cambridge University Press.

Fenwick T., Edwards R., Sawchuk A. (2011). Emerging Approaches to Educational Research: Tracing the Socio-Material. England: Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

Goergalou, G. (2015). I make the rules on my Wall: Privacy and identity management practices on Facebook. Discourse and Communication, 10(10), 40–64.

Gershon, I. (2010). Media Ideologies: An Introduction. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 20(2), 283–293.

Goffman, E. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Doubleday.

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction Ritual. Pantheon.

Gold, R. (1958). Roles in Sociological Field Observations. Social Forces, 36(3), 217–223.

Hallett, R. E., & Barber, K. (2014). Ethnographic research in a cyber era. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 43, 306–330.

Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2007). Ethnography: Principles in practice (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Henninger N.M. (2020). ‘I gave someone a good death’: Anonymity in a community of Reddit’s medical professionals. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 26 (5–6), 1391–1410.

Hine, C. (2000). Virtual Ethnography. Sage.

Hine C. (2008). Virtual ethnography: Modes, varieties, affordances. Nigel Fielding RMLGB (eds). Los Angeles: Sage.

Hine, C. (2015). Ethnography for the Internet: Embedded, Embodied and Everyday. Bloomsbury Academic.

Hoey, B. A. (2014). A simple introduction to the practice of ethnography and guide to ethnographic fieldnotes. Marshall University Digital Scholar.

Hutchins, E. (1995). Cognition in the wild. MIT Press.

Käihkö, I. (2018). Conflict chatnography: Instant messaging apps, social media and conflict ethnography in Ukraine. Ethnography, 21(1), 71–91.

Kerrigan, F., & Hart, A. (2016). Theorising digital personhood: A dramaturgical approach. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(17–18), 1701–1721.

Kozinets, R. (2010). Netnography: Doing Ethnographic Research Online (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE.

Kozinets, R. (2015). Netnography: Redefined (2nd ed.). Sage.

Kozinets, R., Scaraboto, D., & Parmentier, M. A. (2018). Evolving netnography: How brand auto-netnography, a netnographic sensibility, and more-than-human netnography can transform your research. Journal of Marketing Management, 34(3–4), 231–242.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Legitimate Peripheral Participation in Communities of Practice. Situated Learning Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leigh, J., Disney, T., Warwick, L., Fergusin, H., Beddoe, L., & Cooner, T. S. (2021). Revealing the hidden performances of social work practice: The ethnographic process of gaining access, getting into place and impression management. Qualitative Social Work, 20, 1078–1095.

Ling C., Balcı U., Blackburn J., Stringhini G. (2021). "A First Look at Zoombombing," 2021 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 1452–1467, https://www.computer.org/csdl/proceedings-article/sp/2021/893400b047/1t0x8Vq5Zde (Accessed 24 Nov 2021).

MacLeod, A. (2016). Understanding the culture of graduate medical education: The benefits of ethnographic research. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 8, 142–144.

MacLeod, A., Cameron, P., Kits, O., & Tummons, J. (2019). Technologies of exposure: Videoconferenced distributed medical education as a sociomaterial practice. Academic Medicine, 94(3), 412–418.

MacLeod A, Fournier C. (2017). Residents’ use of mobile technologies: three challenges for graduate medical education. BMJ Simulation & Technology Enhanced Learning. 2017;3(3). https://stel.bmj.com/content/3/3/99 (Accessed 24 Nov 2021)

MacLeod, A., Kits, O., Whelan, E., Fournier, C., Wilson, K., Power, G., Mann, K., Tummons, J., & Brown, P. A. (2015). Sociomateriality: A theoretical framework for studying distributed medical education. Academic Medicine, 90(11), 1451–1456.

Marcus, G. E. (1995). Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology, 2, 95–117.

Markham A. (2005). The Methods, Politics, and Ethics of Representation in Online Ethnography. In Denzin N, Lincoln Y (eds). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Meeuwissen, S. N. E., Gijselaers, W. H., van Oorschot, T. D., Wolfhagen, I. H. A. P., & Oude Egbrink, M. G. A. (2021). Enhancing team learning through leader inclusiveness: A one-year ethnographic case study of an interdisciplinary teacher team. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 33(5), 498–508.

Morison, T., Gibson, A. F., Wigginton, B., & Crabb, S. (2015). Online research methods in critical psychology: Methodological opportunities for critical qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12, 223–232.

Murthy, D. (2008). Digital Ethnography: An Examination of the Use of New Technologies for Social Research. Sociology, 42(5), 837–855.

Nissenbaum, H. (2004). Privacy as contextual integrity. Washington Law Review, 79, 119. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol79/iss1/10

Numerato, D. (2016). Behind the digital curtain: Ethnography, football fan activism and social change. Qualitative Research, 16(5), 575–591.

Orlikowski, W. J., & Scott, S. V. (2008). 10 Sociomateriality: Challenging the Separation of Technology. Work and Organization, the Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 433–474.

Ozkula, S. M. (2020). Culture, and Commercial Context in Social Media Ethics. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 15(1–2), 77–86.

Pink, S., Horst, H., Postill, J., Hjorth, L., Lewis, T., & Tacchi, J. (2015). Digital Ethnography: Principles and Practice. Sage Publications Ltd.

Politou, E., Alepis, E., & Patsakis, C. (2018). Forgetting personal data and revoking consent under the GDPR: Challenges and proposed solutions. Journal of Cybersecurity, 4(1), 1–20.

Reeves S., Peller J., Goldman J., & Kitto S. (2013). Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE Guide No. 80. Medical Teacher, 35(8), e1365–79. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/0142159X.2013.804977 (accessed 24 Nov 2021).

Robards, B. (2013). Friending Participants: Managing the Researcher-Participant Relationship on Social Network Sites. Young, 21(3), 217–235.

Robards, B., & Lincoln, S. (2017). Uncovering longitudinal life narratives: Scrolling back on Facebook. Qualitative Research, 17(6), 715–730.

Robinson, L., & Schulz, J. (2009). New avenues for sociological inquiry: Evolving forms of ethnographic practice. Sociology, 43, 685–698.

Seligman, L. J., & Estes, B. P. (2020). Innovations in Ethnographic Methods. American Behavioural Scientist, 64(2), 176–197.

Tagg, C., Lyons, A., Hu, R., & Rock, F. (2017). The ethics of digital ethnography in a team project. Applied Linguistics Review, 8(2–3), 271–292.

Thompson, A., Stringfellow, L., Maclean, M., & Nazzal, A. (2020). Ethical considerations and challenges for using digital ethnography to research vulnerable populations. Journal of Business Research., 124(2), 676–683.

Varis, P. (2016). Digital Ethnography. In A. Georgakopoulou & T. Spilioti (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Language and Digital Communication (pp. 55–68). Routledge.

Wieringa S., Engebretsen E., Heggen K., Greenhalgh T. (2018). How Knowledge Is Constructed and Exchanged in Virtual Communities of Physicians: Qualitative Study of Mindlines Online. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(2), e34 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29396385/ (Accessed 24 Nov 2021)

Wesch, M. (2012). The Digital Ethnography Class of Spring. ‘Anonymous, Anonymity, and the End(s) of Identity and Groups Online: Lessons from the First Internet-Based Superconsciousness. In N. L. Whitehead & M. Wesch (Eds.), Human no More: Digital subjectivities, Unhuman Subjects and the End of Anthropology. Colorado: University of Colorado Press.

West, S. M. (2017). Raging against the machine: Network gatekeeping and collective action on social media platforms. Media and Communication Media and Communication, 5(3), 28–36.

Wilson, S., & Peterson, L. (2002). The anthropology of online communities. Annual Review of Anthropology, 31, 449–467.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to the anonymous reviewers and Editors whose comments on earlier drafts much improved the focus of the paper.

Funding

This work was unfunded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JC had the original idea for this paper. Both authors contributed equally to the development of the content and revising the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical permission was not required for this paper, which is a synopsis of publicly-available literature.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cleland, J., MacLeod, A. Disruption in the space–time continuum: why digital ethnography matters. Adv in Health Sci Educ 27, 877–892 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-022-10101-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-022-10101-1