Abstract

Clinical reasoning is the thought process that guides practice. Although a plethora of clinical reasoning studies in healthcare professionals exists, the majority appear to originate from Western cultures. A scoping review was undertaken to examine clinical reasoning related research across Asian cultures. PubMed, SciVerse Scopus, Web of Science and Airiti Library databases were searched. Inclusion criteria included full-text articles published in Asian countries (2007 to 2019). Search terms included clinical reasoning, thinking process, differential diagnosis, decision making, problem-based learning, critical thinking, healthcare profession, institution, medical students and nursing students. After applying exclusion criteria, n = 240 were included in the review. The number of publications increased in 2012 (from 5%, n = 13 in 2011 to 9%, n = 22) with a steady increase onwards to 12% (n = 29) in 2016. South Korea published the most articles (19%, n = 46) followed by Iran (17%, n = 41). Nurse Education Today published 11% of the articles (n = 26), followed by BMC Medical Education (5%, n = 13). Nursing and Medical students account for the largest population groups studied. Analysis of the articles resulted in seven themes: Evaluation of existing courses (30%, n = 73) being the most frequently identified theme. Only seven comparative articles showed cultural implications, but none provided direct evidence of the impact of culture on clinical reasoning. We illuminate the potential necessity of further research in clinical reasoning, specifically with a focus on how clinical reasoning is affected by national culture. A better understanding of current clinical reasoning research in Asian cultures may assist curricula developers in establishing a culturally appropriate learning environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Clinical reasoning, a central component of healthcare professionals’ competence, comprises the thought process that guides medical practice (Eva, 2005; Rogers, 1983). Clinical reasoning includes a range of critical thinking, judgment, decision making and problem-solving skills (Ajjawi & Higgs, 2008; Eva, 2005; Griffits, Hines, Moloney, & Ralph, 2017; Gummesson, Sundén, & Fex, 2018; Norman, 2005; Rogers, 1983). Learning how to reason can be viewed as a thinking process prone to ‘disposition’, since clinical reasoning can be influenced by personal attitudes, cultural perspectives and preconceptions (McCarthy, 2003; Scheffer & Rubenfeld, 2000). Despite clinical reasoning being culturally influenced, research investigating it across Asian settings appears to be scarce. Indeed, a recent systematic review of 58 articles (2000–2015) on teaching and assessing clinical reasoning for enhancing professional competence uncovered no research of Asian origin, and merely focused on Western models of teaching and assessing clinical reasoning (Guraya, 2016).

Research in clinical reasoning

Over the past decades, the focus of research in clinical reasoning has shifted from understanding the process and factors associated with clinical reasoning to the subject of mental representations relating to expert knowledge (Norman, 2005). There is also a growing body of literature that has explored strategies of teaching or assessment in clinical reasoning. The hypothetic-deductive model, pattern recognition and dual process reasoning model are the most frequently identified strategies; while case studies with simulation, direct observation, script concordance tests and think aloud exams are the most commonly addressed assessment methods (Gruppen, 2017; Yazdani, Hosseinzadeh, & Hosseini, 2017). Furthermore, it has been proposed that diagnostic errors may arise from flaws in the thinking processes during clinical reasoning (Norman et al., 2017). Research has highlighted the strategies employed in the training of thinking processes that might improve clinical reasoning and decision making, hence leading to better quality in healthcare (Griffits et al., 2017; Gummesson et al., 2018; Lambe, O'Reilly, Kelly, & Curristan, 2016; Schmidt & Mamede, 2015).

In terms of cultural differences in clinical reasoning, literature is scarce. One mixed methods study examined differences in clinical reasoning of students from Asian (Indonesian) and Western (Australian) medical education settings (Findyartini, Hawthorne, McColl, & Chiavaroli, 2016). The study found that Western students appeared to be more independent self-learners, but their Asian counterparts tended to be more teacher-dependent; Western students and their tutors asserted a belief that classroom problem-based learning was sufficient for learning of clinical reasoning skills, but Asian students and tutors tended to believe them to be developed mainly in clinical settings. However, clinical reasoning in this study was defined apriori as an Analytic process. As such, the comparison of thinking processes between the two cultures was not examined.

Culture and cognition: analytic vs Holistic thinking

Understanding the influence of culture on clinical reasoning is a key issue given today’s globalisation of healthcare education which tends to adopt Western approaches as the default (Hodges, Maniate, Martimianakis, Alsuwaidan, & Segouin, 2009). However, culture does influence thought, which in turn impacts on reasoning (including reasoning clinically). Broadly speaking, different cultures appear to favor different styles of thinking (Nakamura, 1985). Note, the theoretical basis of cross-cultural studies are underpinned by the concept of national context effects (Straus, 2009) and as such are focused at the level of the group—not the individual (i.e. individual differences within cultures are specifically acknowledged).

In terms of thinking more broadly (i.e. general cognition), according to Nisbett and his colleagues, Eastern cultures tend to favour an ‘Holistic’ approach to thinking, conversely Western cultures tend to favour an ‘Analytic’ approach (Nisbett & Masuda, 2003; Nisbett, Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001). Indeed, some cognitive differences have been observed between Analytic and Holistic ways of thinking in research on general cognition which have implications for culture, clinical reasoning and decision making (Ji, Peng, & Nisbett, 2000; Nisbett & Miyamoto, 2005; Nisbett et al., 2001).

Based on this premise, using an East Asian sample to represent Holistic thinkers and a Western sample to represent Analytic thinkers, several differences between Analytic and Holistic thinkers have been evidenced: Analytic thinkers’ confidence and performance in a cognitive task significantly increases when a sense of control is induced, but this is not the case for Holistic thinkers; Analytic thinkers tend to explain behavior concerning internal attributes, whereas Holistic thinkers tend to explain behavior regarding the interaction between internal attributes and situational factors; Analytic thinkers predominately use deterministic rules to categorise objects, whereas Holistic thinkers prefer to draw on similarities and relationships amongst objects; Analytic thinkers tend to make choices between opposing positions, whereas Holistic thinkers tend to avoid conflicts and find a compromise solution between opposing positions; Analytic thinkers tend to have a linear perspective towards the future, however, Holistic thinkers prefer a more dialectical perspective, believing that certain trends will change in the future (Choi, Koo, & Jong An, 2007; Nisbett & Masuda, 2003; Nisbett et al., 2001).

Due to the unique characteristics of each style of thinking, it has been argued that decision making across Eastern and Western cultural contexts differs (Li, Masuda, Hamamura, & Ishii, 2018). For example, studies have provided evidence about the varying amounts of information decision-makers gather before their final decisions, with some studies linking it to Analytic or Holistic styles of thinking (Choi, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2008; Choi et al., 2007; Li et al., 2018; Nisbett & Miyamoto, 2005). Thus, by contrast to Holistic thinkers, it has been argued that Analytic thinkers assume that information in every event can be understood in isolation from the whole. Alternatively, Holistic thinkers tend to consider many aspects of information before coming to a decision (Choi, Dalal, Kim-Prieto, & Park, 2003; Choi et al., 2007, 2008; Levett-Jones et al., 2010). Analytic and Holistic thinkers can also differ when deciding on the type of information considered to be essential (Nisbett & Masuda, 2003). In combining information, Holistic thinkers tend to seek a compromise between conflicting pieces of information, while Analytic thinkers tend to make a principal choice by carefully scrutinising each piece of information (Choi et al., 2003, 2007; Nisbett et al., 2001). We can therefore anticipate that the clinical reasoning of health professionals from Western and Eastern contexts might be dissimilar to one another.

The scoping review

Scoping reviews are the appropriate review methodology for assessing and understanding the extent of knowledge in a field when no previous review has been undertaken (Peters et al., 2020). This scoping review therefore aims to address the current gap in the literature by focusing on clinical reasoning research that has been published arising from Asian cultures. In doing so, we aim to ascertain the extent to which clinical reasoning has been the focus research in Asia, including: which countries have contributed to this literature, which healthcare professions have been studied, how clinical reasoning has been conceptualized, what aspects of clinical reasoning are the focus of interest (e.g. teaching evaluation, assessment, cultural differences), where studies have been published and the funding status of the research. Such a scoping of the literature will identify key gaps alongside issues such as research rigour.

Methods

With the Arksey and O'Malley framework (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005) and the recommendations by Levac and Peters (Levac, Colquhoun, & O'Brien, 2010; Peters et al., 2020), our scoping review approach involves the following steps: (1) scoping review questions; (2) search strategy; (3) study screening and selection; (4) data extraction; and (5) analysis and presentation of results (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005; Hidalgo et al., 2011; Khalil et al., 2016). We chose not to include the optional step of consultation with practitioners and consumers prior to developing the protocol for a number of reasons, including: (1) our research team comprise key international personnel who are also practitioners and consumers of this work across Asia; (2) the restricted timescale in which we had to develop the protocol; and (3) the financial logistics in gathering an appropriate international consultation group, running the sessions and post-session work.

Review questions

Initially, we began with the broad research question: “What is the current status of clinical reasoning research arising from Asian cultures?”. Following a team discussion, the following specific research questions (RQs) were developed:

-

RQ1: How many clinical reasoning articles have been published from an Asian origin between 2007 and 2019?

-

RQ2: Which Asian countries have researched clinical reasoning?

-

RQ3: Which healthcare professionals have been studied?

-

RQ4: What types of studies have been undertaken (methodologies)?

-

RQ5: What is the main focus of the published studies?

-

RQ6: What does the literature tell us about cultural differences and similarities?

-

RQ7: In what journals have the studies been published, in what language, and what is the indexing status of those journals?

-

RQ8: What is the funding status of the studies?

-

RQ9: Are there any trends across RQs 1–7 over time?

The rationales for these questions are as follows. Firstly, given the lack of Asian studies cited in the clinical reasoning literature, we wished to understand the prevalence and origin of studies (RQs 1 & 2). An understanding of the healthcare professions included in the literature and the types of studies enables us to better describe the landscape of the literature (RQs 3 & 4). The focus of the studies enables us to ascertain the gaps in the literature (RQ5). Specifically, we will investigate the extent to which culture has been examined across clinical reasoning studies (RQ 6). We are also interested in where articles are published and the extent to which studies on clinical reasoning across Asia are funded. This provides us with proxy information about how this research is valued (e.g. whether it is considered worthy of being funded and published in quality journals: RQs 7–8). Finally, examining trends across all these aspects over time enables us to gain a deeper understanding of the general state of clinical reasoning across Asia (e.g. is it more prevalent now? is it funded more now? what are the key issues in the literature over time? RQ 9).

Defining the scope

Research on clinical reasoning is fragmented due to the range of definitions, conceptualisations and terminology that have been variously used (Young et al., 2018). Indeed, we note from our own discussions whilst developing inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study, that the terms clinical reasoning, critical thinking and clinical decision making have overlapping elements. We also note that some professional domains have a preference for one term over another. For example, literature in medicine has a tendency to use the term clinical reasoning whereas the nursing literature tends to use the term critical thinking. Furthermore, both of these terms include an element of clinical decision making. Indeed, according to Simmons (2010), clinical reasoning is ‘‘a complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information and weigh alternative actions’’. It is the sum of decision making and critical thinking processes (Harris 1993). Given that the terms decision making, critical thinking, and clinical reasoning have fuzzy boundaries (Young et al., 2018), with decision making and critical thinking sometimes being used as sub-processes within clinical reasoning, and with clinical reasoning and critical thinking sometimes being used interchangeably across the healthcare professions education literature, we decided to include them all in our search strategy. Furthermore, because we are interested in the range of sub-processes within clinical reasoning, we were also open to these processes within the healthcare professions education literature.

Search strategy

Four electronic databases were utilized: PubMed, SciVerse Scopus, Web of Science and Airiti Library. These were used to capture a wide range of possible articles including those published in non-English language (e.g. Airiti holds a large collection of Chinese language academic publications). Following the database searches, snowballing through hand searching reference lists results in a total of 11 additional articles. We undertook two searches across a 13-year period: 2007–2019 (initially, 15 October 2017 for the 9-year period 2007–2016, and updated on 09 March 2020 to include 2017–2019). The search terms included clinical reasoning, thinking process, differential diagnosis, decision making, problem-based learning, and critical thinking, combined with healthcare profession or institution, medical or nursing students, and trainees or residents (see online Supplement Table 1 for the full strategy). The major search strings used were (“clinical reasoning” OR “thinking process” OR “differential diagnosis” OR “decision making” OR “problem-based learning” OR “critical thinking”) AND (“healthcare profession” OR “institution” OR “medical students” OR “nursing students” OR “trainees” OR “residents”).

Screening

All articles were collected and stored using EndNote® to eliminate duplicates. The title and abstract of citations were screened independently by two reviewers. Articles retrieved were included in the review if they met the following criteria: (a) Original full-text articles focused on clinical reasoning or its derivatives (b) Peer-reviewed articles published across the years 2007 and 2019 (c) Studies with country of publications from the list of 50 Asian countries ("United Nations geoscheme for Asia," 2021). Decisions regarding Asian countries were relatively straightforward, except for those originating from Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey, as these states are in both continents of Asia and Europe. For these countries we consulted a map to determine which side of the boundary they were in before making a decision to include or exclude them. The country of publication for each article was then determined by the first author’s affiliation. Team members agreed that the start date of 2007 for inclusion should be used because it is a key transitional point in medical education in Taiwan, a leader in medical education research more generally in Asia due to its’ unique funding structure (Monrouxe, Liu, Yau, & Babovic, 2020).

The full inclusion/exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Inclusion: peer-reviewed full journal articles, original data, from 2007-2019, publications with at least one researcher from an Asian country, full-text available and focuses on clinical reasoning (or its derivatives);

-

Exclusion: non-peer-reviewed articles, conference abstracts, letters, articles without full-text available or published by researchers outside of Asia.

Data extraction

After screening, all relevant articles were imported to ATLAS.ti™ from EndNote®. A set of codes for charting content was developed to extract study characteristics required to answer our research questions such as publication year, journal type, study locations, methodology, participants and funding resources. This charting process was reviewed and pretested by the research team before implementation.

For many codes, the category is obvious (e.g. publication year, journal) but for the content codes (RQ5) relating to the focus of the studies, we undertook a thematic analysis. All authors independently read a subset of the articles to develop themes. We then met to develop an initial coding framework. Included in this framework were specific codes for the key terms of clinical reasoning, critical thinking and decision making. This enabled us to clarify the specific focus of each article as we used the authors’ terminology. Coding the data in this way meant that we could include all articles, even those that did not clearly define the specific construct of study. Further meetings throughout the process enabled us to resolve conflicts and ensure consistency across the coding. Each article was coded to only one main content theme for RQ5, although sometimes more than one could have been possible. Our rationale was to enable us to examine trends over time, so we coded to the main focus of the article, rather than having multiple coding for some articles.

Analysis and presentation of results

The intention of a scoping review is to present an overview comprising basic descriptive analyses (e.g. frequency counts) of extracted data, rather than synthesizing results or codings of the included studies (Peters et al., 2020). We therefore use article ‘demographic’ coding (e.g. year, country, journal, etc.) and thematic coding of content to report the data. Frequencies of codes are summarized and presented in graphical form where possible. Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) was used to facilitate descriptive analyses and graphical summaries.

Results

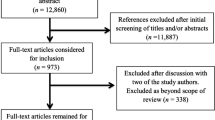

The two separate searches yielded a total of 14,321 potentially relevant articles. After the duplication check and screening, 278 met the eligibility criteria. Following data characterization, 240 articles were included for full coding (Fig. 1).

Year, Country, Participants and Methodology (RQs 1–4)

Figure 2 illustrates an increase in number of published articles annually between 2007 and 2019. As we can see, particularly from 2012 (9%, n = 22), there is a steady climb in the number of studies published until 2016 (12%, n = 29) when publications reduce slightly between 2017 and 2019. Over 60% of articles were published by researchers from five countries: South Korea (19%, n = 46), Iran (17%, n = 41), China (15%, n = 36), Taiwan (9%, n = 22) and Turkey (8%, n = 19), see Supplement Table 3. Nursing and medical students were the most common study participants (42%, n = 105 and 34%, n = 86, respectively; see online supplement Table 4). Quantitative approaches (72%, n = 173) were the most prevalent type with an increasing trend, followed by qualitative (20%, n = 49), while mixed-methods (8%, n = 18) approaches were the least common (Supplement Fig. 1).

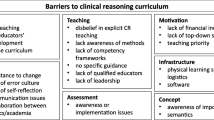

The main focus of the published studies (Study themes: RQ5)

We categorized the articles into seven content themes see Table 1 (and online supplement Table 5) based on the frequency in our data, namely: (1) Evaluation of existing courses; (2) Research into critical thinking; (3) Research into decision making; (4) Evaluation of assessment; (5) Research into clinical reasoning; (6) Development of teaching; and (7) Description of concepts, teaching or learning. These content themes contained a variety of sub-themes that came together within each category. We also used coding frequency to support the key issues identified within our content themes (rather than cherry-picking). However, we chose not to report specific numbers of these sub-themes within the themes as they will be relatively low and therefore adding little to our overall understanding (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020).

Evaluation of existing courses

This category has the highest number of articles coded to it (30%, n = 73), including studies examining the effects of teaching practices (e.g. problem-based learning, high-fidelity simulation) on critical thinking and decision making skills (Agha, 2019; Ahn & Kim, 2015; Lee, Kim, & Park, 2015b, Lee, Lee, Lee, & Bae, 2016; Okubo et al., 2012; Tayyeb, 2013; Yoo, Cho, & Kim, 2019; Yu, Zhang, Xu, Wu, & Wang, 2013; Zarifsanaiey, Amini, & Saadat, 2016). Some articles report comparative studies, for example, suggesting that problem-based learning approaches leads to greater improvement in critical thinking skills than traditional lectures (Choi, Lindquist, & Song, 2014; Gholami et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2012).

Research into critical thinking

This second category comprises articles relating to the assessment of critical thinking (30%, n = 71). Common assessments are the California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (and its Chinese version), the California Critical Thinking Skills, Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (and its Chinese version), Critical Thinking Disposition Scale-Korean version and Watson–Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (Atay & Karabacak, 2012; Chen et al., 2010; Huang, Chen, Yeh, & Chung, 2012; Kaya & Yalniz, 2012; Kim, Moon, Kim, Kim, & Lee, 2014; Moattari, Soleimani, Moghaddam, & Mehbodi, 2014; Pai, Eng, & Ko, 2013; Pilevarzadeh, Mashayekhi, Faramarzpoor, & Beigzade, 2014; Suliman & Halabi, 2007; Woo & Tak, 2015; Zhang et al., 2017). Among the subscales of these instrument tools, low scores of truth-seeking, confidence, systematicity and inference are frequently reported in Chinese, Taiwanese, Korean, Turkish, Iranian and Pakistani medical and nursing students (Atay & Karabacak, 2012; Chen et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2012; Kaya & Yalniz, 2012; Kim et al., 2014; Mahmoodabad, Nadrian, & Nahangi, 2012; Moattari et al., 2014; Pai et al., 2013; Penjvini & Hejrani, 2015; Wong, 2007; Woo & Tak, 2015; Yeh, Chen, & Huang, 2009; Yildirim, Ozkahraman, Korkmaz, & Ersoy, 2011; Zhang & Lambert, 2008; Zhang, Li, Wu, & Chen, 2009; Zia & Dar, 2019).

Clinical decision making

Articles in this category (12%, n = 28) tend to focus on strategies to develop decision making skills, such as pattern recognition, the implementation of evidence-based medicine or multidisciplinary educational programmes (Hachesu et al., 2012; Ladak et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2009; Marcelo et al., 2013; Phua, See, Khalizah, Low, & Lim, 2012; Ramezani-Badr, Nasrabadi, Yekta, & Taleghani, 2009). One study in particular indicates that preference of cognitive approaches for clinical decision making may be subject to factors, such as gender, specialty, years of practice or training background of the physician, despite both rational and experiential techniques are used in clinical decision making process (Alshaalan, Alharbi, & Alattas, 2019).

Evaluation of assessment

Articles coded to this theme (11%, n = 26) primarily report studies that evaluate competence levels in clinical reasoning using Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCE) or Script Concordance Tests (SCT) (Abdelkhalek, Hussein, Sulaiman, & Hamdy, 2009; Iravani, Amini, Doostkam, & Dehbozorgian, 2016; Park, Kang, Lee, & Myung, 2015; See, Tan, & Lim, 2014; Tsai et al., 2008). The SCT is the most common assessment in studies and is considered to be a reliable and validated tool to evaluate clinical reasoning (Iravani et al., 2016; Nazim et al., 2019; Sadeghi et al., 2019; See et al., 2014; Tan, Tan, Kandiah, Samarasekera, & Ponnamperuma, 2014). The SCT is able to differentiate between participants of varying levels of competence and utilized in different clinical disciplines including urology, psychiatry, otolaryngology and neurology (Iravani et al., 2016; Kazour, Richa, Zoghbi, El-Hage, & Haddad, 2017; Nazim et al., 2019; Tan et al., 2014).

Clinical reasoning

This theme comprises articles focusing on methods or influential factors for the learning of clinical reasoning (6%, n = 15). For example, two studies demonstrate the effectiveness of learning approaches (cognitive-mapping or illness scripts) in improving medical students’ reasoning performance (Lee et al., 2010; Wu, Wang, Grotzer, Liu, & Johnson, 2016). The use of Summarize history and physical findings, Narrow the differential, Analyze the differential, Probe preceptor about uncertainties, Plan management, and Select case-related issues for self-study, the SNAPPS is considered another approach for promoting clinical reasoning skills in residents and medical students (Kapoor, Kapoor, Kalraiya, & Longia, 2017; Sawanyawisuth, Schwartz, Wolpaw, & Bordage, 2015). In addition, two studies show the positive impact of problem-solving workshop or tutorial on developing clinical reasoning skills in medical students (Matinpour et al., 2014; Rehan, Farooqi, Khan, & Rehman, 2017). Factors associated with clinical reasoning are examined in two further studies: one concludes that it is the culture within the classroom, or the clinical environment, that is likely to exert an influence on medical students’ clinical reasoning through the hidden curriculum (Vidyarthi, Kamei, Chan, Goh, & Lek, 2015); while the other study determines emotional intelligence as one variable that can be used for clinical reasoning prediction (Ashoorion, Liaghatdar, & Adibi, 2012).

Development of teaching

Articles coded to this theme (5%, n = 12) primarily focus on investigating new teaching methods for clinical reasoning, decision making or critical thinking. For example, after the implementation of a summary statement practice for teaching clinical reasoning, an idea adopted from Western clinical training, one Japanese study observed the improvement of clinical reasoning skills in resident physicians (Heist, Kishida, Deshpande, Hamaguchi, & Kobayashi, 2016). A mnemonic checklist (TWED, T = threat, W = what else, E = evidence and D = dispositional factors) is introduced as an innovation created to reduce cognitive bias to enable medical students make better quality of clinical decisions (Chew, Durning, & van Merrienboer, Chew, Durning, & van Merrienboer, 2016). Some studies present a new teaching method that involves common teaching models combined with another intervention. For improving various clinical skills in nursing or medical students, these new methods include the development of a simulation scenario and evaluation checklist, the integration of the virtual patient system with the conventional OSCE, the incorporation of social media into problem-based training, and the use of group discussion, simulation and problem-solving interventions in a blended training program (Awan, Awan, Alshawwa, Tekian, & Park, 2018; Lee, Jeong, Kang, Kim, & Lee, 2015a; Lin et al., 2013; Parandavar, Rezaee, Mosallanejad, & Mosallanejad, 2019).

Description of concepts, teaching or learning

Articles coded to this category (4%, n = 10) comprise mainly descriptive studies. For example, the effectiveness of problem-based learning on critical thinking and the importance of integrating this learning approach with applications such as portfolios or internet technologies are frequently discussed (Azer, 2008; Chan, 2013; Fan, Jiang, Shi, Wang, & Li, 2018; Jia, Zeng, & Zhang, 2018; Kong, Qin, Zhou, Mou, & Gao, 2014).

Studies with comparative topics in relation to cultural issues (RQ6)

There are 7 articles (Table 2) which include comparative topics or descriptions in relation to cultural issues (Chan, 2013; Chiang & Chan, 2014; Findyartini et al., 2016; Salsali, Tajvidi, & Ghiyasvandian, 2013; Sawanyawisuth et al., 2015; Sommers, 2018; Wang, Chien, & Twinn, 2012). Of these, one study compared clinical reasoning teaching and learning in Australia with that in Indonesia (Findyartini et al., 2016). This study found that Indonesian students score lower on the Flexibility subscale of the Diagnostic Thinking Inventory than their Australian counterparts. Focus group interview data from this study also suggested a tendency toward uncertainty avoidance in students from the Indonesian context (Findyartini et al., 2016).

One study from Thailand applied the learning approach of clinical reasoning SNAPPS derived from a Western culture to students at the Thailand University (Sawanyawisuth et al., 2015). The authors from this study suggested that the cultural differences in terms of Thai students’ passive nature may result in expression of uncertainties far less often than their American counterparts during case presentations (Wolpaw, Papp, & Bordage, 2009). Two further studies conducted in Hong Kong and China, respectively also compared the critical thinking disposition or clinical decision making between their local nursing participants and their counterparts in the studies from other Western countries (Chiang & Chan, 2014; Wang et al., 2012). By comparison to their Western counterparts, the Hong Kong nursing students had lower critical thinking scores (Chiang & Chan, 2014) while the Chinese registered nurses showed a lower level of autonomy in decision making (Wang et al., 2012).

Two literature reviews (Salsali et al., 2013; Sommers, 2018) and one systematic review (Chan, 2013) examined critical thinking dispositions in nursing education. Salsali et al. (2013) addressed differences in critical thinking dispositions between Asian and Non-Asian nursing students. Two other reviews discussed the influence of different cultural backgrounds on teaching or learning of critical thinking (Chan, 2013; Sommers, 2018). In the systematic review by Chan (2013), the author suggests that the cultural background of learners and educators plays an important role in learning and teaching critical thinking. Considering the finding that most studies included in Chan’s review were conducted in Western countries, there is also an emphasis on the need for more studies exploring cultural diversity in critical thinking or clinical reasoning (Chan, 2013).

Journals, publication language and funding (RQs 7 & 8)

English (91%, n = 219) was the most frequently identified language (Supplement Fig. 2), followed by traditional and simplified Chinese (6%, n = 14), and Korean (3%, n = 7). The majority of articles were published in Nurse Education Today, followed by BMC Medical Education (Supplement Fig. 3). The majority of published articles reported unfunded studies (63%, n = 150: Fig. 3); when studies were funded, this was mainly by local institutions (63% of funded studies, n = 57), but some were nationally funded (32%, n = 29) with the minority being internationally funded (4%, n = 4).

Discussion

Our scoping review of clinical reasoning research across Asia has revealed a number of trends. First of all, the number of studies on clinical reasoning in Asia has increased in both quantity and quality. The funding of studies (mainly institutional but also national) also shows an increase around 2011–2014, although the meaning of why this is the case is unclear. However, international collaboration (and funding) was found to be infrequent and fewer articles are published in non-English languages over the course of the decade. The most frequent topic and target population identified respectively are nursing and nursing students, followed by medical education and medical students. Also, the principal research theme is the evaluation of existing courses, focusing specifically on problem-based learning. Evaluation of assessment is rarely studied in the context of clinical reasoning in Asian countries, as is the process of clinical reasoning and decision making itself. Further, limited attention is placed on the development of research methodology and theory.

Indeed, our findings concur with a recent systematic scoping review of the healthcare professions education research literature from Taiwan (Monrouxe et al., 2020), in which the authors revealed a growing publication trend of healthcare professions education research over twelve years (2006–2017). Furthermore, they also found low international research collaboration, consistent with our study (as reported for RQ6) (Monrouxe et al., 2020). This suggests that the collaborative effort between Western and Eastern international partners is an area to be fostered and strengthened, with a focus on developing more multi-national, cross-cultural research on clinical reasoning. In the context of a body of cognitive research on clinical reasoning that has been predominately undertaken in a single (Western) culture, and given the plethora of research that suggests clear differences in thinking and reasoning between Eastern and Western cultures (Choi et al., 2007, 2008; Li et al., 2018; Nisbett & Miyamoto, 2005), it appears that knowledge around clinical reasoning is particularly biased towards Western cognitive practices. Leveraging various research and development funds that are available in the Asian region (Monrouxe et al., 2020) could be a promising strategy towards developing such work.

We found only a few comparative studies cross-culturally (n = 7). More specifically, there is only one study that actually compares the clinical reasoning in medical students between Asian and Western cultures (Findyartini et al., 2016). The remaining studies are reviews, or those conducted mainly with nursing participants that utilize the exemplary results from Western countries to compare critical thinking with their local findings (Chan, 2013; Chiang & Chan, 2014; Salsali et al., 2013; Sawanyawisuth et al., 2015; Sommers, 2018; Wang et al., 2012). The Asian participants in these studies were often associated with unfavorable critical thinking scores or characteristics considered to be typically found in Asian cultures such as subordination to authority or uncertainty avoidance. This cultural tendency toward uncertainty avoidance and seeking complete information in the Asian context reflects the work by Nisbett and Miyamoto (2005) where Holistic thinkers (representing Eastern cultures) tend to seek a compromise between conflicting pieces of information and consider many aspects of information before coming to a decision (Choi et al., 2003, 2007, 2008; Levett-Jones et al., 2010). While none of the studies relate their findings to the those by Nisbett or Choi, all the authors attributed the differences in their findings to cultural influences with evidence from other literature on culture in their discussion sections.

There has been a paradigm shift in healthcare professions education research from being heavily scientific-oriented to having more inclusion of healthcare professions education research from across the social sciences (Hong et al., 2010; Monrouxe & Rees, 2009; Schuwirth & van der Vleuten, 2006). That healthcare professions education research more generally has gained in popularity over the years may also explain our finding of increasing trend of research on clinical reasoning in Asia (Eva, 2005; Hong et al., 2010; Monrouxe et al., 2020; Schuwirth & van der Vleuten, 2006). In addition, this might be an indicator for increased awareness among Asian healthcare professions educators on the importance of clinical reasoning in the training of healthcare professionals.

Although we have reviewed the literature on clinical reasoning across Asia, our analysis also raises questions about aggregating Asian countries as one big ‘Asian Culture’. Since Asia is a large continent with very diverse cultures, the question arises, to what extent can the whole of Asia be taken as ‘One Culture’? Approximately 68% (n = 164) of the articles in our study come from five Asian countries (South Korea, Iran, China, Taiwan and Turkey), while the remaining 32% originate from another 16 countries. It might be that countries in Asia are better grouped according to them possessing a more or less similar culture with one another, rather than together (Hoftede, Hofstede, & Minkov, 2010).

It is interesting to note that the most prominent studied area in clinical reasoning is related to the evaluation of existing courses and critical thinking, with the least prominent being related to the development and description of concepts, teaching or learning. This suggests that current research focuses more on the learning of clinical reasoning, rather than the fundamental process of clinical reasoning itself. Such a focus suggests that there might be a tendency to accept prevailing Western understandings of how healthcare professionals think and reason clinically as being how healthcare professionals across the world—irrespective of their cultural upbringing. This is despite there being evidence that suggests this might not be the case.

Challenges and strengths

The lack of critical appraisal, or possibility of missing relevant studies, has been reported as a key challenge in scoping reviews (Brien, Lorenzetti, Lewis, Kennedy, & Ghali, 2010; Feehan, Beck, Harris, MacIntyre, & Li, 2011; Hand & Letts, 2009). However, scoping reviews are not intended to be exhaustive (Boydell, Gladstone, Volpe, Allemang, & Stasiulis, 2012; Cameron, Tsoi, & Marsella, 2008; Levac et al., 2010). We also considered the fuzzy boundaries between the terminologies used to be a limitation (Young et al., 2018). For example, some researchers used the term clinical reason, while others used the term critical thinking, both of which have overlapping elements and sometimes used interchangeably. Although we used authors’ terminology to drive our coding, this does not overcome the core issue of this poorly integrated body of literature. Another limitation is that concepts similar to clinical reasoning may be described using different terms in local languages. This leads to the potential bias of the lack of sufficient locally-published articles in non-English journals in this review. However, due to the range of Asian collaborators on this study, we were able to access some non-English but relevant articles, thus the bias of this issue has been minimized to the lowest extent possible.

Implications for research

To our knowledge, this is the first scoping review study exploring the current status of clinical reasoning research across Asia. However, we were unable to identify cultural differences in the process of clinical reasoning between East Asian and Western cultures, despite indirect evidence of existing distinct critical thinking dispositions between these two groups. We would argue that it is important to promote fundamental research in clinical reasoning across different cultural contexts in order to fully understand the underlying mechanism of healthcare professionals’ clinical reasoning processes. These fundamental results will inform researchers and educators on the best way to teach, learn, evaluate and assess the clinical reasoning abilities within different cultural environments. Furthermore, such research might consider comparing groups of countries based on their distinct cultural similarities, rather than having a “one Asia” approach. One potential way forward for this would be to utilise Hofstede’s classification of national cultures (Hoftede et al., 2010). A deeper analysis in future work might reveal interesting findings about differences in thinking and clinical reasoning patterns within Asia as well as outwith. A better understanding of the healthcare education systems in a culturally sensitive manner can therefore provide Asian healthcare professionals with adequate clinical reasoning curricula tailored appropriately for the Asian learning environment.

References

Abdelkhalek, N. M., Hussein, A. M., Sulaiman, N., & Hamdy, H. (2009). Faculty as simulated patients (FSPs) in assessing medical students’ clinical reasoning skills. Education for Health, 22(3), 323.

Agha, S. (2019). Effect of simulation based education for learning in Medical Students: A mixed study method. JPMA-Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 69(4), 545–554.

Ahn, H., & Kim, H. Y. (2015). Implementation and outcome evaluation of high-fidelity simulation scenarios to integrate cognitive and psychomotor skills for Korean nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 35(5), 706–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.01.021

Ajjawi, R., & Higgs, J. (2008). Learning to reason: A journey of professional socialisation. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 13(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-006-9032-4

Alshaalan, A. A., Alharbi, M. K., & Alattas, K. A. (2019). Preference of cognitive approaches for decision making among anesthesiologists’ in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 13(3), 191–196. https://doi.org/10.4103/sja.SJA_792_18

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Ashoorion, V., Liaghatdar, M. J., & Adibi, P. (2012). What variables can influence clinical reasoning? Journal of Research in Medical Sciences: THe Official Journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, 17(12), 1170–1175.

Atay, S., & Karabacak, U. (2012). Care plans using concept maps and their effects on the critical thinking dispositions of nursing students. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 18(3), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2012.02034.x

Awan, Z. A., Awan, A. A., Alshawwa, L., Tekian, A., & Park, Y. S. (2018). Assisting the integration of social media in problem-based learning sessions in the Faculty of Medicine at King Abdulaziz University. Medical Teacher, 40(sup1), S37-s42. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2018.1465179

Azer, S. A. (2008). Use of portfolios by medical students: Significance of critical thinking. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 24(7), 361–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1607-551x(08)70133-5

Boydell, K., Gladstone, B., Volpe, T., Allemang, B., & Stasiulis, E. (2012). The production and dissemination of knowledge: A scoping review of arts-based health research forum: qualitative social research sozialforschung. Forum Qualitative Social Research, 13(1), 32.

Bradley, E., & Nolan, P. (2007). Impact of nurse prescribing: A qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 59(2), 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04295.x

Brien, S. E., Lorenzetti, D. L., Lewis, S., Kennedy, J., & Ghali, W. A. (2010). Overview of a formal scoping review on health system report cards. Implementation Science, 5(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-2

Cajulis, C. B., & Fitzpatrick, J. J. (2007). Levels of autonomy of nurse practitioners in an acute care setting. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 19(10), 500–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00257.x

Cameron, J. I., Tsoi, C., & Marsella, A. (2008). Optimizing stroke systems of care by enhancing transitions across care environments. Stroke, 39(9), 2637–2643. https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.107.501064

Carryer, J., Gardner, G., Dunn, S., & Gardner, A. (2007). The core role of the nurse practitioner: Practice, professionalism and clinical leadership. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16(10), 1818–1825. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01823.x

Chan, Z. C. Y. (2013). A systematic review of critical thinking in nursing education. Nurse Education Today, 33(3), 236–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.01.007

Chen, J., Chen, Y. L., Zheng, H. X., Li, Y. P., Chen, B., Wan, X. L., & Lin, Y. (2010). Medical education model with core competency as guide, evidence-based medicine as carrier and lifelong learning as purpose (1): Current status of critical thinking on medical students. Chinese Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine, 10(3), 298–302.

Chew, K. S., Durning, S. J., & van Merrienboer, J. J. G. (2016). Teaching metacognition in clinical decision making using a novel mnemonic checklist: An exploratory study. Singapore Medical Journal, 57(12), 694–700. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2016015

Chiang, V. C. L., & Chan, S. S. C. (2014). An evaluation of advanced simulation in nursing: A mixed-method study. Collegian, 21(4), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2013.05.003

Choi, E., Lindquist, R., & Song, Y. (2014). Effects of problem-based learning vs. traditional lecture on Korean nursing students’ critical thinking, problem-solving, and self-directed learning. Nurse Education Today, 34(1), 52–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.02.012

Choi, I., Choi, J. A., & Norenzayan, A. (2008). Culture and decisions. In D. J. Koehleer & N. Harvey (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of judgment and decision making malden. Blackwell Publishing.

Choi, I., Dalal, R., Kim-Prieto, C., & Park, H. (2003). Culture and judgment of causal relevance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(1), 46–59.

Choi, I., Koo, M., & Jong An, C. (2007). Individual differences in analytic versus holistic thinking. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(5), 691–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206298568

Eva, K. W. (2005). What every teacher needs to know about clinical reasoning. Medical Education, 39(1), 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01972.x

Facione, N., & Facione, P. (2007). CCTDI test manual 2007 edition. In: Millbrae, CA: Insight Assessment, The California Academic Press.

Fan, C., Jiang, B., Shi, X., Wang, E., & Li, Q. (2018). Update on research and application of problem-based learning in medical science education. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 46(2), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.21105

Feehan, L. M., Beck, C. A., Harris, S. R., MacIntyre, D. L., & Li, L. C. (2011). Exercise prescription after fragility fracture in older adults: A scoping review. Osteoporosis International, 22(5), 1289–1322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1408-x

Findyartini, A., Hawthorne, L., McColl, G., & Chiavaroli, N. (2016). How clinical reasoning is taught and learned: Cultural perspectives from the University of Melbourne and Universitas Indonesia. BMC Medical Education, 16, 185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0709-y

Gholami, M., Moghadam, P. K., Mohammadipoor, F., Tarahi, M. J., Sak, M., Toulabi, T., & Pour, A. H. H. (2016). Comparing the effects of problem-based learning and the traditional lecture method on critical thinking skills and metacognitive awareness in nursing students in a critical care nursing course. Nurse Education Today, 45, 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.06.007

Griffits, S., Hines, S., Moloney, C., & Ralph, N. (2017). Characteristics and processes of clinical reasoning in nurses and factors related to its use: A scoping review protocol. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, 15(12), 2832–2836. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2016-003273

Gruppen, L. D. (2017). Clinical reasoning: Defining it, teaching it, assessing it, studying it. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18(1), 4–7. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2016.11.33191

Gummesson, C., Sundén, A., & Fex, A. (2018). Clinical reasoning as a conceptual framework for interprofessional learning: A literature review and a case study. Physical Therapy Reviews, 23(1), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10833196.2018.1450327

Guraya, S. Y. (2016). The Pedagogy of Teaching and Assessing Clinical Reasoning for Enhancing the Professional Competence: A Systematic Review. Biotech Res Asia, 13(3), 169.

Hachesu, P. R., Ahmadi, M., Rezapoor, A., Salahzadeh, Z., Farahnaz, S., & Maroufi, N. (2012). Clinical care improvement with use of health information technology focusing on evidence based medicine. Healthcare Information Research, 18(4), 290.

Harris, I. B. (1993). New expectations for professional competence and accountability (pp. 17–52). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hand, C., & Letts, L. (2009). Occupational therapy research and practice involving adults with chronic diseases: A scoping review and internet scan. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists.

Heist, B. S., Kishida, N., Deshpande, G., Hamaguchi, S., & Kobayashi, H. (2016). Virtual patients to explore and develop clinical case summary statement skills amongst Japanese resident physicians: A mixed methods study. BMC Medical Education. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0571-y

Hidalgo, L. A. S. I., Le, B. L., Owen, I., & Fletcher, G. (2011). An evidence-based approach to scoping reviews. The Electronic Journal Information Systems Evaluation, 14(1), 46–52.

Hodges, B. D., Maniate, J. M., Martimianakis, M. A., Alsuwaidan, M., & Segouin, C. (2009). Cracks and crevices: Globalization discourse and medical education. Medical Teacher, 31(10), 910–917.

Hoftede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind: Intercultural cooperation and its importance for survival. McGraw-Hill.

Hong, X., Yanling, C., Jin, C., Bin, C., Xiaoli, W., Yuan, L., & Huixian, Z. (2010). The current status of medical education literature in Chinese-language journals. Medical Teacher, 32(11), e460–e466. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.507712

Huang, Y. C., Chen, H. H., Yeh, M. L., & Chung, Y. C. (2012). Case studies combined with or without concept maps improve critical thinking in hospital-based nurses: A randomized-controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(6), 747–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.01.008

Iravani, K., Amini, M., Doostkam, A., & Dehbozorgian, M. (2016). The validity and reliability of script concordance test in otolaryngology residency training. Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism, 4(2), 93–96.

Jenkins, S. D. (2011). Cross-cultural perspectives on critical thinking. Journal of Nursing Education, 50(5), 268–274. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20110228-02

Ji, L. J., Peng, K., & Nisbett, R. E. (2000). Culture, control, and perception of relationships in the environment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(5), 943–955.

Jia, X., Zeng, W., & Zhang, Q. (2018). Combined administration of problem- and lecture-based learning teaching models in medical education in China: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (baltimore), 97(43), e11366. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000011366

Kapoor, A., Kapoor, A., Kalraiya, A., & Longia, S. (2017). Use of SNAPPS model for pediatric outpatient education. Indian Pediatrics, 54(4), 288–290.

Kawashima, A. (2003). Critical thinking integration into nursing education and practice in Japan: Views on its reception from foreign-trained Japanese nursing educators. Contemporary Nurse, 15(3), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.15.3.199

Kaya, H., & Yalniz, N. (2012). Critical thinking dispositions of emergency nurses in Turkey: A cross-sectional study. Hong Kong Journal of Emergency Medicine, 19(3), 198–203.

Kazour, F., Richa, S., Zoghbi, M., El-Hage, W., & Haddad, F. G. (2017). Using the script concordance test to evaluate clinical reasoning skills in psychiatry. Academic Psychiatry, 41(1), 86–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-016-0539-6

Khalil, H., Peters, M., Godfrey, C. M., McInerney, P., Soares, C. B., & Parker, D. (2016). An evidence-based approach to scoping reviews. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 13(2), 118–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12144

Kim, D. H., Moon, S., Kim, E. J., Kim, Y. J., & Lee, S. (2014). Nursing students’ critical thinking disposition according to academic level and satisfaction with nursing. Nurse Education Today, 34(1), 78–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.03.012

Kleinpell-Nowell, R. (2001). Longitudinal survey of acute care nurse practitioner practice: Year 2. AACN Clinical Issues, 12(3), 447–452. https://doi.org/10.1097/00044067-200108000-00012

Kong, L. N., Qin, B., Zhou, Y. Q., Mou, S. Y., & Gao, H. M. (2014). The effectiveness of problem-based learning on development of nursing students’ critical thinking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(3), 458–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.06.009

Ladak, L. A., Premji, S. S., Amanullah, M. M., Haque, A., Ajani, K., & Siddiqui, F. J. (2013). Family-centered rounds in Pakistani pediatric intensive care settings: Non-randomized pre- and post-study design. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(6), 717–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.05.009

Lambe, K. A., O’Reilly, G., Kelly, B. D., & Curristan, S. (2016). Dual-process cognitive interventions to enhance diagnostic reasoning: A systematic review. BMJ Quality and Safety, 25(10), 808–820. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004417

Lee, A., Joynt, G. M., Ho, A. M. H., Keitz, S., McGinn, T., Wyer, P. C., & Grp, E. B. M. T. S. W. (2009). Tips for teachers of evidence-based medicine: Making sense of decision analysis using a decision tree. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 24(5), 642–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-0918-8

Lee, A., Joynt, G. M., Lee, A. K. T., Ho, A. M. H., Groves, M., Vlantis, A. C., & Aun, C. S. T. (2010). Using illness scripts to teach clinical reasoning skills to medical students. Family Medicine, 42(4), 255–261.

Lee, J., Lee, Y., Lee, S., & Bae, J. (2016). Effects of high-fidelity patient simulation led clinical reasoning course: Focused on nursing core competencies, problem solving, and academic self-efficacy. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 13(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/jjns.12080

Lee, J. J., Jeong, H. C., Kang, K. A., Kim, Y. J., & Lee, M. N. (2015a). Development of a simulation scenario and evaluation checklist for patients with asthma in emergency care. Cin-Computers Informatics Nursing, 33(12), 546–554. https://doi.org/10.1097/cin.0000000000000193

Lee, S. J., Kim, S. S., & Park, Y. M. (2015b). First experiences of high-fidelity simulation training in junior nursing students in Korea. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 12(3), 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/jjns.12062

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Levett-Jones, T., Hoffman, K., Dempsey, J., Jeong, S.Y.-S., Noble, D., Norton, C. A., & Hickey, N. (2010). The ‘five rights’ of clinical reasoning: An educational model to enhance nursing students’ ability to identify and manage clinically ‘at risk’ patients. Nurse Education Today, 30(6), 515–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2009.10.020

Li, L. M. W., Masuda, T., Hamamura, T., & Ishii, K. (2018). Culture and decision making: Influence of analytic versus holistic thinking style on resource allocation in a fort game. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(7), 1066–1080. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022118778337

Lin, C. W., Clinciu, D. L., Swartz, M. H., Wu, C. C., Lien, G. S., Chan, C. Y., & Li, Y. C. (2013). An integrative OSCE methodology for enhancing the traditional OSCE program at Taipei medical university ospital-a feasibility study. BMC Medical Education. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-102

Mahmoodabad, S. S., Nadrian, H., & Nahangi, H. (2012). Critical thinking ability and its associated factors among preclinical students in Yazd Shaheed Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences (Iran). Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 26(2), 50–57.

Mangena, A., & Chabeli, M. M. (2005). Strategies to overcome obstacles in the facilitation of critical thinking in nursing education. Nurse Education Today, 25(4), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2005.01.012

Marcelo, A., Gavino, A., Isip-Tan, I. T., Apostol-Nicodemus, L., Mesa-Gaerlan, F. J., Firaza, P. N., & Fontelo, P. (2013). A comparison of the accuracy of clinical decisions based on full-text articles and on journal abstracts alone: A study among residents in a tertiary care hospital. Evidence-Based Medicine, 18(2), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2012-100537

Matinpour, M., Sedighi, I., Monajemi, A., Jafari, F., Momtaz, H. E., & Ali, S. R. M. (2014). Clinical reasoning and improvement in the quality of medical education. Shiraz E Medical Journal, 15(4), 1–4.

McCarthy, M. C. (2003). Detecting acute confusion in older adults: Comparing clinical reasoning of nurses working in acute, long-term, and community health care environments. Research in Nursing and Health, 26(3), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.10081

Moattari, M., Soleimani, S., Moghaddam, N. J., & Mehbodi, F. (2014). Clinical concept mapping: Does it improve discipline-based critical thinking of nursing students? Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 19(1), 70–76.

Monrouxe, L. V., Liu, G. R., Yau, S. Y., & Babovic, M. (2020). A scoping review examining funding trends in health care professions education research from Taiwan (2006–2017). Nursing Outlook, 68(4), 417–429.

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2009). Picking up the gauntlet: Constructing medical education as a social science. Medical Education, 43(3), 196–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03272.x

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2020). When I say quantification in qualitative research. Medical Education, 54(3), 186–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14010

Nakamura, H. (1985). Ways of thinking of Eastern peoples: India, China, Tibet, Japan. In P. P. Wiener (Ed.) Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Nazim, S. M., Talati, J. J., Pinjani, S., Biyabani, S. R., Ather, M. H., & Norcini, J. J. (2019). Assessing clinical reasoning skills using Script Concordance Test (SCT) and extended matching questions (EMQs): A pilot for urology trainees. Journal of Advances in Medical Education and Professionalism, 7(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.30476/jamp.2019.41038

Nisbett, R. E., & Masuda, T. (2003). Culture and point of view. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100(19), 11163–11170. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1934527100

Nisbett, R. E., & Miyamoto, Y. (2005). The influence of culture: Holistic versus Analytic perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(10), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.004

Nisbett, R. E., Peng, K., Choi, I., & Norenzayan, A. (2001). Culture and systems of thought: Holistic versus Analytic cognition. Psychological Review, 108(2), 291–310.

Norman, G. (2005). Research in clinical reasoning: Past history and current trends. Medical Education, 39(4), 418–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02127.x

Norman, G. R., Monteiro, S. D., Sherbino, J., Ilgen, J. S., Schmidt, H. G., & Mamede, S. (2017). The causes of errors in clinical reasoning: cognitive biases, knowledge deficits, and dual process thinking. Academic Medicine, 92(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001421

Okubo, Y., Ishiguro, N., Suganuma, T., Nishikawa, T., Takubo, T., Kojimahara, N., & Yoshioka, T. (2012). Team-based learning, a learning strategy for clinical reasoning, in students with problem-based learning tutorial experiences. Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine, 227(1), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.227.23

Pai, H. C., Eng, C. J., & Ko, H. L. (2013). Effect of caring behavior on disposition toward critical thinking of nursing students. Journal of Professional Nursing, 29(6), 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.05.006

Parandavar, N., Rezaee, R., Mosallanejad, L., & Mosallanejad, Z. (2019). Designing a blended training program and its effects on clinical practice and clinical reasoning in midwifery students. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 8, 131–131. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_22_18

Park, W. B., Kang, S. H., Lee, Y. S., & Myung, S. J. (2015). Does objective structured clinical examinations score reflect the clinical reasoning ability of medical students? American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 350(1), 64–67. https://doi.org/10.1097/maj.0000000000000420

Penjvini, S., & Hejrani, M. S. (2015). Critical thinking and clinical decision making skills in pediatric nursing students. Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences, 6(2), 62–68.

Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbies-20-00167

Phua, J., See, K. C., Khalizah, H. J., Low, S. P., & Lim, T. K. (2012). Utility of the electronic information resource UpToDate for clinical decision making at bedside rounds. Singapore Medical Journal, 53(2), 116–120.

Pilevarzadeh, M., Mashayekhi, F., Faramarzpoor, M., & Beigzade, M. (2014). Relationship between critical thinking disposition and self-esteem in bachelor nursing students. Biosciences Biotechnology Research Asia, 11(2), 973–978. https://doi.org/10.13005/bbra/1369

Ramezani-Badr, F., Nasrabadi, A. N., Yekta, Z. P., & Taleghani, F. (2009). Strategies and criteria for clinical decision making in critical care nurses: A qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 41(4), 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01303.x

Rehan, R., Farooqi, L., Khan, H., & Rehman, R. (2017). Comparison of two interactive tutorial methods: Results from a medical college in Karachi. JPMA-Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 67(2), 196–199.

Rogers, J. C. (1983). Eleanor clarke slagle lectureship–1983; clinical reasoning: The ethics, science, and art. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 37(9), 601–616.

Sadeghi, A., Ali Asgari, A., Moulaei, N., Mohammadkarimi, V., Delavari, S., Amini, M., & Charlin, B. (2019). Combination of different clinical reasoning tests in a national exam. Journal of Advances in Medical Education and Professionalism, 7(4), 230–234. https://doi.org/10.30476/jamp.2019.83101.1083

Salsali, M., Tajvidi, M., & Ghiyasvandian, S. (2013). Critical thinking dispositions of nursing students in Asian and non-Asian countries: A literature review. Glob J Health Sci, 5(6), 172–178. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v5n6p172

Sawanyawisuth, K., Schwartz, A., Wolpaw, T., & Bordage, G. (2015). Expressing clinical reasoning and uncertainties during a Thai internal medicine ambulatory care rotation: Does the SNAPPS technique generalize? Medical Teacher, 37(4), 379–384. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.947942

Scheffer, B. K., & Rubenfeld, M. G. (2000). A consensus statement on critical thinking in nursing. Journal of Nursing Education, 39(8), 352–359.

Schmidt, H. G., & Mamede, S. (2015). How to improve the teaching of clinical reasoning: A narrative review and a proposal. Medical Education, 49(10), 961–973. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12775

Schuwirth, L. W., & van der Vleuten, C. P. (2006). Challenges for educationalists. BMJ, 333(7567), 544–546. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38952.701875.94

See, K. C., Tan, K. L., & Lim, T. K. (2014). The script concordance test for clinical reasoning: Re-examining its utility and potential weakness. Medical Education, 48(11), 1069–1077. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12514

Simmons, B. (2010). Clinical reasoning: concept analysis. Journal of advanced nursing, 66(5), 1151–1158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05262.x.

Sommers, C. L. (2018). Measurement of critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment in culturally diverse nursing students-A literature review. Nurse Education in Practice, 30, 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.04.002

Stenner, K., & Courtenay, M. (2008). Benefits of nurse prescribing for patients in pain: Nurses’ views. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 63(1), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04644.x

Straus, M. A. (2009). The national context effect: An empirical test of the validity of cross-national research using unrepresentative samples. Cross-Cultural Research THe Journal of Comparative Social Science, 43(3), 183–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069397109335770

Suliman, W. A., & Halabi, J. (2007). Critical thinking, self-esteem, and state anxiety of nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 27(2), 162–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2006.04.008

Tan, K., Tan, N. C., Kandiah, N., Samarasekera, D., & Ponnamperuma, G. (2014). Validating a script concordance test for assessing neurological localization and emergencies. European Journal of Neurology, 21(11), 1419–1422. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12373

Tayyeb, R. (2013). Effectiveness of problem based learning as an instructional tool for acquisition of content knowledge and promotion of critical thinking among medical students. JCPSP-Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan, 23(1), 42–46.

Tsai, J. C., Liu, K. M., Lee, K. T., Yen, J. C., Yen, J. H., Liu, C. K., & Lai, C. S. (2008). Evaluation of the effectiveness of postgraduate general medicine training by objective structured clinical examination–-pilot study and reflection on the experiences of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 24(12), 627–633.

United Nations geoscheme for Asia. (2021). Retrieved from https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/#geo-regions

Vidyarthi, A. R., Kamei, R., Chan, K., Goh, S. H., & Lek, N. (2015). Factors associated with medical student clinical reasoning and evidence based medicine practice. International Journal of Medical Education, 6, 142–148. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.563a.5dd0

Wang, Y., Chien, W. T., & Twinn, S. (2012). An exploratory study on baccalaureate-prepared nurses’ perceptions regarding clinical decision making in mainland China. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(11–12), 1706–1715. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03925.x

Wolpaw, T., Papp, K. K., & Bordage, G. (2009). Using SNAPPS to facilitate the expression of clinical reasoning and uncertainties: A randomized comparison group trial. Academic Medicine, 84(4), 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819a8cbf

Wong, M. S. (2007). A prospective study on the development of critical thinking skills for student prosthetists and orthotists in Hong Kong. Prosthetics and Orthotics International, 31(2), 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/03093640600983931

Woo, H. Y., & Tak, Y. R. (2015). Critical thinking disposition, professional self-concept and caring perception of nursing students in Korea. International Journal of Bio-Science and Bio-Technology, 7(3), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.14257/ijbsbt.2015.7.3.13

Wu, B., Wang, M., Grotzer, T. A., Liu, J., & Johnson, J. M. (2016). Visualizing complex processes using a cognitive-mapping tool to support the learning of clinical reasoning. BMC Medical Education, 16(1), 10369. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0734-x

Yazdani, S., Hosseinzadeh, M., & Hosseini, F. (2017). Models of clinical reasoning with a focus on general practice: A critical review. Journal of Advances in Medical Education and Professionalism, 5(4), 177–184.

Yeh, M. L., Chen, H. H., & Huang, J. P. (2009). Affective dispositions toward critical thinking in college-level nursing students. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare Research, 5(3), 193–200.

Yildirim, B., Ozkahraman, S., Korkmaz, M., & Ersoy, S. (2011). Examination of critical thinking disposition in nursing. HealthMED, 5(6), 1549–1557.

Yoo, D. M., Cho, A. R., & Kim, S. (2019). Satisfaction with and suitability of the problem-based learning program at the Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 16, 20.

Young, M., Thomas, A., Lubarsky, S., Ballard, T., Gordon, D., Gruppen, L. D., & Durning, S. J. (2018). Drawing boundaries: The difficulty in defining clinical reasoning. Academic Medicine, 93(7), 990–995. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000002142

Yu, D. H., Zhang, Y. Q., Xu, Y., Wu, J. M., & Wang, C. F. (2013). Improvement in critical thinking dispositions of undergraduate nursing students through problem-based learning: A crossover-experimental study. Journal of Nursing Education, 52(10), 574–581. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20130924-02

Zarifsanaiey, N., Amini, M., & Saadat, F. (2016). A comparison of educational strategies for the acquisition of nursing student’s performance and critical thinking: simulation-based training vs. integrated training (simulation and critical thinking strategies). BMC Medical Education, 16, 150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-016-0812-0

Zhang, C., Fan, H., Xia, J., Guo, H., Jiang, X., & Yan, Y. (2017). The Effects of reflective training on the disposition of critical thinking for nursing students in China: A controlled trial. Asian Nurs Res (korean Soc Nurs Sci), 11(3), 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2017.07.002

Zhang, H., & Lambert, V. (2008). Critical thinking dispositions and learning styles of baccalaureate nursing students from China. Nursing and Health Sciences, 10(3), 175–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2008.00393.x

Zhang, Y., Chen, G., Fang, X., Cao, X., Yang, C., & Cai, X. Y. (2012). Problem-based learning in oral and maxillofacial surgery education: The Shanghai hybrid. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 70(1), e7–e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2011.03.038

Zhang, Y. Q., Li, L. S., Wu, P., & Chen, Y. (2009). Investigation and analysis of critical thinking ability in medical students. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (medical Science), 29(7), 869–872.

Zia, A., & Dar, U. F. (2019). Critical thinking: Perception and disposition of students in a Medical College of Pakistan. JPMA Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association, 69(7), 968–972.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology (R.O.C.): [grant number MOST 109-2511-H-182-002] and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taiwan (grant number: CDRPG3J0041).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, CY., Jenq, CC., Chandratilake, M. et al. A scoping review of clinical reasoning research with Asian healthcare professionals. Adv in Health Sci Educ 26, 1555–1579 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-021-10060-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-021-10060-z