Abstract

The Olympia oyster, Ostrea lurida Carpenter, was formerly widespread in many US Pacific coast estuaries. Following dramatic declines in the late 1800s and early 1900s, this species is now the focus of renewed restoration efforts. Restoration is undertaken for brood stock rehabilitation as well as a range of ecosystem services such as filtration; however, these ecosystem services are as yet poorly quantified. We present the first laboratory measurements of filtration rates (FR) for O. lurida, to which we fit a model of FR as a function of dry tissue weight and water temperature. We find that O. lurida has a FR at optimum temperature similar to previously established means across oyster species at 1 g dry tissue weight (DTW), but lower than many Crassostrea species. We also find that the allometric exponent relating FR to DTW in O. lurida is lower than the previously published mean across oyster species. Based on our derived filtration rates and historical data, we estimate the historic impact of filtration by O. lurida in five Pacific coast estuaries. We find that historic O. lurida populations did not have the capacity to filter the full volume of the estuary within the estuary residence time in any of the estuaries examined. This result is primarily driven by the low water temperatures and the short estuary residence times that typify the Pacific coast. We conclude that, unlike Crassostrea virginica Gmelin on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, the Olympia oyster was not historically a dominant force in regulating seston concentrations at large scales in Pacific coast estuaries. Given the differences in the ecological role and habitat structure of these two oyster species, we recommend that analogies between them be drawn with caution. We discuss the implications of our results for developing restoration objectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Oysters are filter-feeding bivalves that historically formed reefs or beds in estuaries throughout temperate latitudes (Stenzel 1971). Both oysters and the complex physical habitats they build may provide a number of important ecosystem services, including the direct provision of food, filtration of the water column (Grizzle et al. 2008), enhanced denitrification rates (Newell et al. 2002), the enhancement of non-oyster fish stocks (Peterson et al. 2003), and coastal protection (Scyphers et al. 2011). Most detailed studies on these services have focused on Crassostrea virginica (Gmelin, 1791) reefs on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States (see Coen et al. 2007); yet, similar benefits are attributed to other oyster species, such as the Olympia oyster, Ostrea lurida Carpenter 1864 on the Pacific coast (White et al. 2009). These analogies are drawn despite numerous studies highlighting differences between C. virginica and O. lurida as regards their morphology (Kellogg 1915), physiology (Elsey 1935), environmental tolerance (Stenzel 1971), and the structure of formed habitats (Stafford 1915), all of which may affect the delivery of those ecosystem services. As ecosystem service delivery becomes an increasingly important concept in the management of marine resources, assumptions of functional equivalency should be evaluated and additional data collected as necessary.

O. lurida was formerly abundant on the Pacific coast of the United States (Bancroft 1890), where it was harvested at low intensity for thousands of years (Barrett 1963). Populations of O. lurida collapsed, however, soon after commercialization of the fishery and rising demand in the mid 1800s (Kirby 2004). Initially, the decline in landings was met with concern and the propagation of this species was the focus of research and numerous investigations (see Baker 1995 for a full bibliography), but interest in the native oyster waned soon after the successful propagation of the faster growing introduced Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg, 1793). While O. lurida persists in a number of Pacific coast estuaries, it is generally a rare component of the biota, represented by scattered individuals (Polson and Zacherl 2009), such that the habitat is widely believed to be functionally extinct in estuaries south of Puget Sound, Washington, USA (Beck et al. 2011; zu Ermgassen et al. 2012). The species’ current range stretches from northern British Columbia, Canada, to Baja California, Mexico in the South (Polson and Zacherl 2009).

Since 2000, there have been renewed efforts to restore O. lurida on the Pacific coast (Cook et al. 2000), involving a broad range of stakeholders including government agencies, industry, tribes, and conservation organizations (Peter-Contesse and Peabody 2005). The motivations to restore are also diverse, including brood stock rehabilitation and the return of various ecosystem services such as filtration, enhanced nutrient cycling, and provision of habitat for other species (Peabody and Griffin 2008; White et al. 2009). With the expansion and increasing success of restoration efforts (McGraw 2009), there is a growing need to calculate the ecosystem service benefits of O. lurida, such that restoration planning and advocacy can take place with greater transparency and a stronger knowledge base.

Filtration of the water column by filter-feeding organisms such as oysters is an important ecological function in aquatic systems (Gili and Coma 1998; Prins et al. 1998). The potential to enhance this ecosystem service is one of the key motivations to restore oysters on the Atlantic coast (e.g., Rossi-Snook et al. 2010). Filtration results in the deposition of organic and inorganic particles to the benthos, which may lead to enhanced denitrification rates in the sediments (Newell et al. 2002), and the enhanced richness and abundance of benthic macrofauna and microbes (Norkko et al. 2001; Nocker et al. 2004). Furthermore, sediment nutrient enrichment (Booth and Heck 2009) and the increased irradiance resulting from the removal of seston may promote the growth of submerged aquatic vegetation (Newell and Koch 2004), which is a critical nursery habitat for a wide range of marine species (Heck et al. 2003). As such, filtration can be considered a critical ecosystem service.

Filtration rates (FR) can vary widely among bivalve species (Moehlenberg and Riisgaard 1979; Riisgaard 1988) and have not previously been determined for O. lurida. Here, we present the results of the first laboratory-based measurements of FR by O. lurida and propose a model of FR as it varies with oyster size and temperature. FR can be defined as the volume of water completely cleared of particles per unit time (Newell and Langdon 1996; Dame 2011), which we adopt here. We apply our FR model to historic abundance (ca. 1850–1935) and a higher estimate of potential abundance before commercial exploitation in five Pacific coast estuaries. From these, we estimate the historic contribution of O. lurida to estuary filtration relative to estuarine residence times. This measure can be considered to be an indicator of the impact of filtration by oysters on the estuary more broadly (Dame 2011). We consider the implications of our results for habitat restoration and management where filtration of estuarine waters is a restoration objective.

Materials and methods

Experimental system and specimen collection

We collected O. lurida from Coos Bay, Oregon, on July 14, 2010 and transferred them to the Hatfield Marine Science Center (HMSC), Newport, Oregon, where we placed them into an outdoor flow-through system. Water used throughout the acclimation period was drawn from Yaquina Bay twice daily at high tide (temperature = 10 ± 2 °C, salinity 27–32 psu) and filtered to < 10 μm. This was supplemented by a continuous supply of algae (Isochrysis galbana Parke 1949, Tetraselmis chuii Butcher 1959, and Chaetocerous gracilis Pantocsek 1892) at a concentration of 15–30 cells μl−1. One month prior to the experiment, we transferred the oysters to a similar flow-through system in the laboratory, kept at a constant 10 °C.

Following this period of acclimation, we measured the total wet weight (TWW) and shell height ([SH] measured from umbo to posterior edge of shell) of all oysters and divided the oysters into weight classes of ± 2 g TWW (Table 1). At least four weight classes were represented at each of the four temperatures tested (Table 1). We placed each group of oysters onto suspended coarse plastic netting within a 10-l aquarium at 10 °C (Fig. 1). By suspending the oysters on the netting, biodeposits could accumulate at the bottom of aquaria, thus preventing waste products from interfering with feeding. Flow rates through aquaria were kept high (60 l h−1) prior to the measurement period to prevent oysters depleting algal concentrations in advance, and oysters were supplied with I. galbana at a concentration of 25 cells μl−1. This concentration was found to be below the threshold for pseudofeces production (Gray, personal observation). Aeration in each aquarium ensured seawater and algae were well mixed. We increased the water temperature in the experimental and control aquaria at a rate of 1 °C day−1 until the desired experimental temperature (10, 15, 20, or 25 °C) was reached. The order of temperature treatments was randomized. Each group of oysters was used only once, with 4–5 groups being tested simultaneously at the same temperature.

While many studies to determine bivalve filtration rates are undertaken on individuals, our study included groups of small-sized oysters to obtain more accurate estimates of average filtration rates for these size classes (Table 1). Our FR estimates averaged for the group do not provide information on maximum individual rates that are commonly reported in physiological studies of bivalve feeding but they are appropriate for estimating mean FR effects for use in ecological models, such as the model described in this study. We verified that our experimental system and approach resulted in reliable FR data for oysters by measuring FR of a range of sizes of Pacific oysters, C. gigas, under different temperature conditions and finding that our weight-specific FR estimates were similar to published values (Gray, unpublished data).

Temperature and oyster size are just two of many variables that affect FR, such as dissolved oxygen concentrations, salinity and seston quality and concentration. These additional variables are, however, difficult to value on the large scale used in this study, as they typically vary greatly spatially or temporally within estuaries (see zu Ermgassen et al. 2013 for an overview). As such, we do not account for these variables in the current model.

Determination of filtration rates

At the start of the measurement period, we stopped the flow of seawater and I. galbana to the experimental aquaria. Algal concentration was measured using an electronic particle counter (Beckman Coulter Counter Z-2; measurement range 3–9 μm). Measurements were taken at 10-min intervals until a 20 % decline in algal concentration was achieved. All experiments were completed within 1 h. Control treatments consisted of 10-l aquaria without oysters to account for algal settlement. Temperature and salinity of seawater were measured using a handheld data recorder (YSI-80) at the start and end of the experimental period to ensure that there were no significant changes.

Filtration rates were determined from the exponential decrease in algal concentration as a function of time using the formula:

where C 0 and C t = algal concentrations at time 0 and at time t (min), respectively; V = volume of water (ml) and n = number of animals per aquarium. As algal settlement was found to be negligible over time (<1 %), it was not necessary to include a correction (Coughlan 1969). Filtration rates were expressed in terms of liters per hour per gram dry tissue weight (DTW) (l h−1 g−1), using a predetermined conversion of DTW = 0.044TWW − 0.043; R 2 adj = 0.93, in which DTW was determined by freeze-drying oyster meats to a constant weight (48 h).

While it is possible that I. galbana was not retained with 100 % efficiency in the laboratory trials (Wilson 1983), I. galbana has an equivalent spherical diameter of 4–6 μm and oysters generally retain particles >4 μm with high efficiency (Moehlenberg and Riisgaard 1978). Furthermore, the cell concentration used in this study (25 cells μl−1) is in the range found to have the highest retention efficiencies as well as the highest pumping rates for O. edulis, Linnaeus, 1758 feeding on I. galbana (Wilson 1983). Therefore, in the absence of species-specific retention efficiencies, we assume 100 % retention efficiency to derive a conservative estimate of FR.

We determined whether temperature and oyster DTW were significant terms in explaining FR by identifying the minimum adequate general linear model (MAM) through the sequential removal of higher-order interactions in R version 2.13.1 (2011-07-08) (Crawley 2007). FR data were log transformed to represent a normal distribution.

Model fitting

Bivalve filtration rates increase nonlinearly as a function of DTW and in response to temperature (Newell and Langdon 1996). This relationship can be written as follows (Cerco and Noel 2005):

where a, b, and c are constants, W is oyster DTW in grams, T 1 is water temperature in °C, and T o is the optimum temperature in °C (defined as the temperature at which maximum filtration rate is achieved). FR is reported in l h−1.

We fitted Eq. 2 to the laboratory-measured filtration rates for O. lurida using the Levenberg–Marquardt nonlinear least squares method (Press et al. 2007) in Mathematica version 7. As FR is known to vary between studies (Cranford et al. 2011), we sought to reduce uncertainty in our model by deriving fits for increasing numbers of estimated parameters, initially substituting the allometric relationship (b) and the optimum temperature (T o) for values derived or estimated from the literature. Fits were subsequently compared by F test to determine whether the estimation of a greater number of parameters with the Levenberg–Marquardt nonlinear least squares method significantly improved the model fit to the data and was therefore justified.

It has been suggested that the allometric component can be universally written as 0.58 for filter-feeding bivalves (Cranford et al. 2011), which we therefore selected as our test value for b. On the other hand, many bivalve species have different thermal optima (Walne 1972), and as there are no previously published estimates of the temperature at which O. lurida achieves maximum filtration, we adopted T o = 25 °C, as the filtration rate measured was greatest at this maximum temperature tested. This value is also similar to the optimal temperature for the related species O. edulis (Newell et al. 1977; Hutchinson and Hawkins 1992).

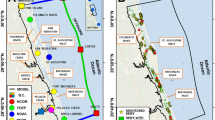

Model application

To determine the mean filtration capacity of the historic oyster population in each estuary by season, we applied Eq. 3 to the historic abundance and size distribution of O. lurida from zu Ermgassen et al. (2012), and current monthly mean temperature for each estuary compiled from publically available National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and National Estuarine Research Reserve System data, for the five Pacific coast estuaries for which data were available (see Table 2 for list of estuaries). None of the Pacific coast estuaries used in this study were found to have maximum monthly temperatures greater than 25 °C. The abundance of oysters documented in zu Ermgassen et al. (2012) represents historical estimates from the late 1800 s and early 1900 s; commercial exploitation began several decades earlier and these do not represent oyster beds in pristine condition. We therefore also calculated the filtration capacity if the same area of oyster bed contained a mean density of 360 oysters m−2, as has been recorded for beds in Port Eliza, British Columbia (Gillespie 2009). While oyster beds in Port Eliza are not pristine, they are among the highest densities documented for remaining O. lurida habitat (Gillespie 2009; COSEWIC 2011). We compared these values to estuary residence times and volumes from Bricker et al. (2007) to calculate the proportion of each estuary’s volume historically filtered by oysters within its residence time. This approach has been used previously to determine the potential large-scale impact of oyster filtration on estuaries within the native range of C. virginica (zu Ermgassen et al. 2013). Residence time is defined as the mean time a particle spends in the estuary. Our calculations assume no significant change between historic and present water temperature (Cane et al. 1997).

To assess whether the difference between the potential role of native oysters on the Pacific and Atlantic/Gulf coasts was driven by the differences in biology between O. lurida and Crassostrea species, or was primarily due to the low residence times of Pacific Coast estuaries, we also determined the proportion of the estuary filtered within the residence time if the native oyster was “replaced” by either C. virginica or C. gigas. In this case, we used the historic densities and areal extent of O. lurida beds, but applied the FR for C. virginica from zu Ermgassen et al. 2012 and C. gigas from Bougrier et al. (1995) and assumed a mean oyster SH of 60 mm, which is more reasonable for these larger, faster growing species, falling in the mid-range of 2-year-old C. virginica as reported in Rothschild et al. (1994).

Results

Filtration rates

Both temperature and oyster size were significant variables in explaining FR for O. lurida (MAM; temperature, F 1,18 = 177.21, P < 0.0001; DTW, F 1,18 = 21.93, P < 0.001).

Model fitting

We found that filtration rate for O. lurida as a function of body size and temperature can be expressed as the equation:

This model explains 96 % of the variability in the measured FR (Table 3).

We were not justified in retaining the universal value of b proposed by Cranford et al. (2011) in our model, with values for the allometric scaling of FR in O. lurida being significantly lower (Table 3). The model fit to the data is graphically illustrated in Fig. 2.

Model application

O. lurida of mean size 35 mm are capable of filtering 2.4 l h−1individual−1 at 25 °C. Beds with average densities of 116 individuals m−2, as were found in historically (Dimick et al. 1941; zu Ermgassen et al. 2012), may process up to 195 l h−1m−2 in summer months in Elkhorn Slough, where the temperature reaches 19.3 °C.

Historic populations of O. lurida filtered a volume equivalent to 1–17 % of the estuary volume within the residence time of the estuary during summer months (Table 4). The volume estimated to have been filtered by these historic populations is nevertheless substantial, reaching 5,248 m3 h−1 in Willapa Bay, WA, in summer months (Fig. 3). If the higher density of 360 oysters m−2 is applied to the five estuaries studied, the volume estimated to have been filtered rises to being equivalent to 3–53 % of the estuary, with 16,241 m3 h−1 filtered in Willapa Bay, WA (Table 4).

Volume of water filtered per hour historically by Ostrea lurida (at 116 oysters m−2) across seasons in five Pacific coast estuaries. See Table 2 for seasonal water temperatures. Note the different y-axis scales

Replacing the native oyster extent with the same density of C. virginica does not affect the potential impact of filtration on seston on a large scale (0–13 % of estuary volume filtered; Fig. 4). Similarly, replacing the native oyster extent with C. gigas does not result in the filtration of a volume equivalent to the volume of the estuary within its residence time (hereafter termed full estuary filtration). Nevertheless, the volume of water filtered is substantially greater and approaches full estuary filtration in San Francisco Bay (11–98 % of estuary volume within the residence time in summer months; Fig. 4).

Illustration of the number of days until the estimated historic O. lurida population and hypothetical C. virginica and C. gigas populations filtered a volume equivalent to the volume of the estuary against the residence time of the estuary. The black line represents the point at which the filtration time equals the residence time. Points above the line are not filtering the full volume of the estuary within the residence time. The points each represent the historic extent of native oyster beds as listed in zu Ermgassen et al. (2012). Unless explicitly stated, the density represented is 116 oysters m−2

Discussion

The FR of 3.08 l g−1 h−1 calculated for O. lurida at optimum temperature falls close to the mean of 3.47 ± 0.49 l g−1 h−1 (± 2 s.e.) for oysters with a DTW of 1 g suggested by Cranford et al. (2011); however, it is substantially lower than the rates of 5 l g−1 h−1 (Newell 1988) and 6.79 l g−1 h−1 (Riisgaard 1988) frequently cited for C. virginica, and 4.83 l g−1 h−1 cited for C. gigas (Bougrier et al. 1995). While there has been significant interest in developing a generalized model for filtration by bivalve filter feeders (e.g., Powell et al. 1992; Cranford et al. 2011), which is useful in the absence of species-specific data, it is also clear that differences in FR between species may be substantial (Moehlenberg and Riisgaard 1979; Riisgaard 1988; Powell et al. 1992). Early work comparing the gill morphology of Crassostrea species with Ostrea species highlighted the likelihood of differences in their feeding ecology (Elsey 1935). This hypothesis was substantiated in a number of studies comparing C. gigas with O. edulis, which found that C. gigas had filtration rates approximately two times higher per unit DTW (Walne 1972; Mathers 1974; Rodhouse and O’Kelly 1981). Although this is not necessarily the case when comparing O. edulis with C. virginica (Shumway et al. 1985), our results support the findings that Ostrea species have lower FR compared to those reported for Crassostrea species at optimum temperature (Fig. 5). Similarly, while the b value determined from our experiment is lower than the mean suggested by Cranford et al. (2011), it is not dissimilar to some b values included in their meta-analysis; for example, Kesarcodi-Watson et al. (2001) reported that Saccostrea commercialis had a b value of 0.32. While it is unsurprising that at the low temperatures typical of the Pacific coast, C. virginica has the lowest FR of the three species examined (Fig. 5) and it does help to illustrate the importance of inter-species differences in biology in determining their impact on the ecosystem. These differences include FR, growth rates, mean size, mean densities, and temperature tolerance. We have attempted in this study to tease apart some of these factors.

A graphical representation of filtration models as related to temperature for O. lurida (solid black line; this study), C. virginica (solid gray line; zu Ermgassen et al. 2013), and C. gigas (dashed black line; Bougrier et al. 1995). All values represent a 1 g dry tissue weight oyster. The shaded area indicates the range of mean summer temperatures in the Pacific coast estuaries included in this study

Ostrea species generally grow more slowly and have a smaller maximum size than Crassostrea species (Stafford 1913; Walne 1972). Furthermore, while very little is known about the density, patch size, and structure of O. lurida beds pre-commercial exploitation, descriptions of intact habitat in British Columbia suggest that O. lurida typically did not reach as high densities within oyster beds as those formed by C. virginica on the Atlantic coast (Stafford 1915). The lower densities and smaller size implicit in these descriptions suggest that O. lurida beds have a lower rate of filtration per unit area than C. virginica reefs.

Whereas oyster populations on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts were often capable of achieving full estuary filtration historically (zu Ermgassen et al. 2013), our estimates for the Pacific coast suggest that O. lurida populations were capable of filtering only a fraction of the volume within the residence time (Table 4). For example, the filtration capacity of the historic O. lurida population in Willapa Bay has been previously conservatively estimated, using oyster abundance extrapolated from harvested biomass statistics, to filter 0.8 % of the estuary within its residence time (Ruesink et al. 2006). We estimate an order of magnitude greater filtration in this study, with the historic population estimated to be capable of achieving ~12 % of full estuary filtration, and the estimated pre-commercial exploitation population ~36 % of full estuary filtration. Full estuary filtration does not equate to the whole volume of the estuary being cleared of all particles due to the high probability of re-filtration within dense beds, re-suspension of particles, selective feeding, and the patchy distribution of oysters (Cranford et al. 2011); however, full estuary filtration values can be used to assess the potential role of bivalves in regulating phytoplankton abundance (Dame 2011).

The lack of evidence of large-scale regulation of seston does not exclude the possibility that filtration may still be an important process in some areas within an estuary. Banas and Hickey (2005) show that the residence time in Willapa Bay is highly uneven throughout the estuary, with water in the upper third of the estuary being retained for 3–5 weeks, while there is near full exchange with every tide near the mouth of the estuary. Oysters are also known to recruit best to the regions in the bay with the greatest retention times (Banas et al. 2007); therefore, it is possible that filtration by O. lurida could have been a structuring process in the upper portion of the bay historically.

The differences in the proportion of the estuary volumes filtered by oysters between the Pacific and Atlantic/Gulf of Mexico coasts cannot simply be explained by the differences between the FR of O. lurida and Crassostrea species, as is illustrated in Fig. 4. The physical attributes of the estuaries, in particular the low residence time of water in Pacific coast estuaries and the low water temperatures (Fig. 5), also play an important role in explaining the difference in the ecological role of native oysters between US coasts. Atlantic coast estuaries are typically coastal plain estuaries, with high nutrient and sediment loads, and relatively long residence times (Uncles et al. 2002). By contrast, Pacific coast estuaries are typically drowned river valleys, with small, high elevation catchments resulting in relatively low nutrient inputs, low sediment retention, and short residence times (Inman and Nordstrom 1971; Bricker et al. 2007). Previous work has illustrated that full estuary filtration values may be appropriate indicators of large-scale impacts on seston within estuaries with long residence times which are dominated by autochthonous primary productivity, but less appropriate in estuaries with short residence times (Dame and Prins 1998; Dame 2011). While this is the case for many Atlantic coast estuaries, the potential impact of full estuary filtration is less well understood for Pacific coast systems, where autochthonous primary productivity is less important and oceanic imports of phytoplankton may dominate (Banas et al. 2007).

The past century has seen the introduction and establishment of C. gigas on the Pacific coast. C. gigas now has a significant presence in some estuaries both in aquaculture facilities and in newly established wild populations (Dumbauld et al. 2011). Given this increased abundance, it is likely that the filtration capacity provided by oysters, albeit a different species, may be returning toward historic values in some estuaries. For example, if we consider the estimated population level filtration rate for cultured C. gigas in Willapa Bay from Banas et al. (2007), we find that ~ 15 % of the estuary could be filtered within the estuary residence time, which lies between our estimated historic and pristine values for the Olympia oyster (Table 4).

While O. lurida restoration is unlikely to lead to large-scale regulation of seston at whole-estuary scales, restoring oyster beds may nevertheless result in significant local impacts on sea grasses. At a local scale, studies using both C. gigas and C. virginica have illustrated that oysters may facilitate sea grass via improved sediment stability (Smith et al. 2009), water clarity (Wall et al. 2008), or nutrient availability (Booth and Heck 2009). The potential positive impact of oyster presence on sea grass appears, however, to be strongly mediated by oyster density, with the impact tending to become negative as oyster or shell density increases (Booth and Heck 2009, Wagner et al. 2012), as well as near reefs (Kelly and Volpe 2007). In contrast to the reef habitat commonly formed by C. gigas and C. virginica, O. lurida beds were historically described as agglomerations of loosely associated individuals (Stafford 1915) that may result in a mixed habitat structure. Indeed, O. lurida beds in British Columbia were described historically as mixed beds of oysters and sea grass, and possible facilitation between the two habitat building species was suggested (Stafford 1915). Therefore, here, as with other ecosystem services, the potential implications of differences between the species should be taken into account.

Where it may not be possible or appropriate to set habitat restoration goals on the basis of the historic status due to, for example, irreversible changes in the abiotic environment (Hobbs et al. 2009), it may be appropriate to set goals on the basis of potential ecosystem services (Hughes et al. 2011). In order to do so, it is necessary to have knowledge of the services potentially provided by the restored habitat. This study is a first step toward quantifying the services that may be provided by O. lurida beds. Further research is needed to determine to what degree our laboratory filtration rates are representative of in situ rates, including how FR is impacted by seston concentrations, as well as to determine the contribution of O. lurida beds to other services of interest, such as denitrification and the provision of fish habitat. While structured habitat is widely accepted to be beneficial to fish, the degree of complexity of the habitat may be important in determining the value of those benefits (Soniat et al. 2004). Historic O. lurida beds had less vertical relief and a lower habitat complexity than C. virginica reefs (Stafford 1915) and are therefore likely to differ in their function as fish habitat. That said, O. lurida is commonly likened to the European oyster O. edulis, due to its similar life history, physiology, and habitat (Elsey 1935; Sherwood 1931), and O. edulis has been observed to have significant habitat value for species in the Wadden Sea (Reise 1982).

In summary, while previous work has documented the decline of O. lurida on the Pacific coast (Steele 1957; Kirby 2004; zu Ermgassen et al. 2012), this study is the first to estimate historic levels of filtration across numerous Pacific coast estuaries, using species-specific FR. We show that filtration by O. lurida may not have played an important role in regulating phytoplankton in estuaries on a large scale, in contrast to C. virginica on the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. However, there is still potential for significant local impacts of filtration by this species. Although parallels are often drawn between oyster habitats in different locations, there is a growing body of evidence that the structures and functions may vary. As efforts are undertaken to restore species and their associated functions in a large number of US estuaries, it is increasingly important that restoration objectives should reflect differences among species and that research is undertaken to better define potential ecosystem services that may be obtained through restoration.

References

Baker P (1995) Review of ecology and fishery of the Olympia oyster, Ostrea lurida with annotated bibliography. J Shellfish Res 14:501–518

Banas NS, Hickey BM (2005) Mapping exchange and residence time in a model of Willapa Bay, Washington, a branching, macrotidal estuary. J Geophys Res 110:C11011

Banas NS, Hickey BM, Newton JA, Ruesink JL (2007) Tidal exchange, bivalve grazing, and patterns of primary production in Willapa Bay, Washington, USA. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 34:123–139

Bancroft HH (1890) History of Washington, Idaho and Montana 1845-1889. The works of Hubert Howe Bancroft. The History Company, Publishers, San Francisco CA

Barrett EM (1963) The California oyster industry. California Fish and Game Bulletin, Vol 123. The Resources Agency of California Department of Fish and Game, San Diego CA

Beck MW, Brumbaugh RD, Airoldi L, Carranza A, Coen LD, Crawford C, Defeo O, Edgar GJ, Hancock B, Kay M, Lenihan HS, Luckenbach MW, Toropova CL, Zhang G, Guo X (2011) Oyster reefs at risk and recommendations for conservation, restoration and management. Bioscience 61:107–116

Booth DM, Heck KL Jr (2009) Effects of the American oyster Crassostrea virginica on growth rates of the seagrass Halodule wrightii. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 389:117–126

Bougrier S, Geairon P, Deslous-Paoli JM, Bacher C, Jonquires G (1995) Allometric relationships and effects of temperature on clearance and oxygen consumption rates of Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg). Aquaculture 134:143–154

Bricker S, Longstaff B, Dennison W, Jones A, Boicourt K, Wicks C, Woerner J (2007) Effects of nutrient enrichment in the nation’s estuaries: a decade of change. National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, Silver Spring

Cane MA, Clement AC, Kaplan A, Kushnir Y, Pozdnyakov D, Seager R, Zebiak SE, Murtugudde R (1997) Twentieth-century sea surface temperature trends. Science 275:957–960

Cerco CF, Noel MR (2005) Assessing a ten-fold increase in the Chesapeake Bay native oyster population. A report to the EPA Chesapeake Bay Program. US Army Engineer Research and Development Center, Vicksburg MS

Coen LD, Brumbaugh RD, Bushek D, Grizzle R, Luckenbach MW, Posey MH, Powers SP, Tolley SG (2007) Ecosystem services related to oyster restoration. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 341:303–307

Cook AE, Schaffer JA, Dumbauld BR, Kauffman BE (2000) A plan for rebuilding stocks of Olympia oysters (Ostreola conchaphila, Carpenter 1857) in Washington state. J Shellfish Res 19:409–412

COSEWIC (2011) COESWIC assessment and status report on the Olympia oyster Ostrea lurida in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa

Coughlan J (1969) The estimation of filtering rate from the clearance of suspensions. Mar Biol 2:356–358. doi:10.1007/bf00355716

Cranford PJ, Evans DA, Shumway SE (2011) Bivalve filter feeding: variability and limits of the aquaculture biofilter. In: Shumway SE (ed) Shellfish aquaculture and the environment. Wiley, pp 81–124

Crawley MJ (2007) The R book. Wiley, Chicester

Dame RF (2011) Ecology of marine bivalves: an ecosystem approach. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Dame R, Prins T (1998) Bivalve carrying capacity in coastal ecosystems. Aquat Ecol 31(4):409–421

Dimick RE, Egland G, Long JB (1941) Native oyster investigations of Yaquina bay, Oregon Progress Report II. Oregon Agricultural Experiment Station, Corvallis, OR

Dumbauld B, Kauffman BE, Trimble AC, Ruesink JL (2011) The Willapa Bay oyster reserves in Washington State: fishery collapse, creating a sustainable replacement, and the potential for habitat conservation and restoration. J Shellfish Res 30:71–83. doi:10.2983/035.030.0111

Elsey CR (1935) On the structure and function of the mantle and gill of Ostrea gigas (Thunberg) and Ostrea lurida (Carpenter). Trans R Soc Can 29 (V):131–158

Gili J-M, Coma R (1998) Benthic suspension feeders: their paramount role in littoral marine food webs. Trends Ecol Evol 13:316–321

Gillespie GE (2009) Status of the Olympia oyster, Ostrea lurida Carpenter 1864, in British Columbia, Canada. J Shellfish Res 28:59–68

Grizzle RE, Greene JK, Coen LD (2008) Seston removal by natural and constructed intertidal eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) reefs: a comparison with previous laboratory studies, and the value of in situ methods. Estuar Coast 31:1208–1220

Heck KL Jr, Hays G, Orth RJ (2003) Critical evaluation of the nursery role hypothesis for seagrass meadows. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 253:123–136

Hobbs RJ, Higgs E, Harris JA (2009) Novel ecosystems: implications for conservation and restoration. TREE 24:599–605

Hughes FMR, Stroh PA, Adams WM, Kirby KJ, Mountford JO, Warrington S (2011) Monitoring and evaluating large-scale, ‘open-ended’ habitat creation projects: a journey rather than a destination. J Nat Conserv 19:245–253. doi:10.1016/j.jnc.2011.02.003

Hutchinson S, Hawkins LE (1992) Quantification of the physiological responses of the European flat oyster Ostrea edulis L. to temperature and salinity. J Molluscan Stud 58:215–226

Inman DL, Nordstrom CE (1971) On the tectonic and morphologic classification of coasts. J Geol 79:1–21

Kellogg JL (1915) Ciliary mechanisms of lamellibranchs with descriptions of anatomy. J Morphol 26:625–701

Kelly JR, Volpe JP (2007) Native eelgrass (Zostera marina L.) survival and growth adjacent to non-native oysters (Crassostrea gigas Thunberg) in the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia. Bot Mar 50:143–150. doi:10.1515/BOT.2007.017

Kesarcodi-Watson A, Lucas JS, Klumpp DW (2001) Comparative feeding and physiological energetics of diploid and triploid Sydney rock oysters, Saccostrea commercialis: I. Effects of oyster size. Aquacult 203:177–193

Kirby M (2004) Fishing down the coast: historical expansion and collapse of oyster fisheries along continental margins. Proc Nat Acad Sci 101:13096–13099. doi:10.1073/pnas.0405150101

Mathers NF (1974) Some comparative aspects of filter-feeding in Ostrea edulis L. and Crassostrea angulata (Lam.) (Mollusca: Bivalve). Proc Malacol Soc Lond 41:89–98

McGraw KA (2009) The Olympia oyster, Ostrea lurida Carpenter 1864 along the West coast of North America. J Shellfish Res 28:5–10

Moehlenberg F, Riisgaard HU (1978) Efficiency of particle retention in 13 species of suspension feeding bivalves. Ophelia 17:239–246

Moehlenberg F, Riisgaard HU (1979) Filtration rate, using a new indirect technique, in thirteen species of suspension-feeding bivalves. Mar Biol 54:143–147

Newell RIE (1988) Ecological changes in Chesapeake Bay: Are they the result of overharvesting the American oyster, Crassostrea virginica? In: Understanding the Estuary: advances in Chesapeake Bay Research, Baltimore, Maryland. Chesapeake Research Consortium Publication, pp 536–546

Newell RIE, Koch EW (2004) Modeling seagrass density and distribution in response to changes in turbidity stemming from bivalve filtration and seagrass sediment stabilization. Estuaries 27:793–806

Newell RIE, Langdon CJ (1996) Mechanisms and physiology of larval and adult feeding. In: Kennedy VS, Newell RIE, Eble AF (eds) The eastern oyster Crassostrea virginica. A Maryland Sea Grant Book, College Park, pp 185–229

Newell RC, Johson LG, Kofoed LH (1977) Adjustment of the components of energy balance in response to temperature change in Ostrea edulis. Oecologia 30:97–110

Newell RIE, Cornwell JC, Owens MS (2002) Influence of simulated bivalve biodeposition and microphytobenthos on sediment nitrogen dynamics: a laboratory study. Limnol Oceanogr 47:1367–1379

Nocker A, Lepo JE, Snyder RA (2004) Influence of an oyster reef on development of the microbial heterotrophic community of an estuarine biofilm. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:6834–6845. doi:10.1128/AEM.70.11.6834-6845.2004

Norkko A, Hewitt JE, Thrush SF, Funnell GA (2001) Benthic-pelagic coupling and suspension-feeding bivalves: linking site-specific sediment flux and biodeposition to benthic community structure. Limnol Oceanogr 46:2067–2072

Peabody B, Griffin K (2008) Restoring the Olympia oyster, Ostrea conchaphila. Habitat Connections 6:1–6

Peter-Contesse T, Peabody B (2005) Reestablishing Olympia oyster populations in Puget Sound, Washington. Puget Sound Restoration Fund

Peterson CH, Grabowski JH, Powers SP (2003) Estimated enhancement of fish production resulting from restoring oyster reef habitat: quantitative valuation. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 264:249–264. doi:10.3354/meps264249

Polson MP, Zacherl DC (2009) Geographic distribution and intertidal population status for the Olympia oyster, Ostrea lurida Carpenter 1864, from Alaska to Baja. J Shellfish Res 28:69–77

Powell EN, Hofmann EE, Klinck JM, Ray SM (1992) Modeling oyster populations I. A commentary on filtration rate. Is faster always better? J Shellfish Res 11:387–398

Press WH, Teukolsky SA, Vetterling WT, Flannery BP (2007) Numerical recipes: the art of scientific computing, 3rd edn. Cambridge University Press, New York

Prins T, Smaal A, Dame R (1998) A review of the feedbacks between bivalve grazing and ecosystem processes. Aquat Ecol 31:349–359

Reise K (1982) Long-term changes in the macrobenthic invertebrate fauna of the Wadden Sea: are polychaetes about to take over? Neth J Sea Res 16:29–36

Riisgaard HU (1988) Efficiency of particle retention and filtration rate in 6 species of Northeast American bivalves. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 45:217–223

Rodhouse PG, O’Kelly M (1981) Flow requirements of the oysters Ostrea edulis L. and Crassostrea gigas Thunb. In an upwelling column system of culture. Aquacult 22:1–10. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(81)90127-7

Rossi-Snook K, Ozbay G, Marenghi F (2010) Oyster (Crassostrea virginica) gardening program for restoration in Delaware’s Inland Bays, USA. Aquacult Int 18:61–67

Rothschild BJ, Ault JS, Goulletquer P, Heral M (1994) Decline of the Chesapeake Bay oyster population: a century of habitat destruction and overfishing. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 111:29–39

Ruesink JL, Feist BE, Harvey CJ, Hong JS, Trimble AC, Wisehart LM (2006) Changes in productivity associated with four introduced species: ecosystem transformation of a “pristine” estuary. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 311:203–215

Scyphers SB, Powers SP, Heck KL, Byron D (2011) Oyster reefs as natural breakwaters mitigate shoreline loss and facilitate fisheries. PLoS ONE 6:e22396

Sherwood HP (1931) The oyster industry in North America: a record of a brief tour of some of the centres of the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, and of a summer in Canada. ICES J Mar Sci 6:361–386

Shumway SE, Cucci TL, Newell RC, Yentsch CM (1985) Particle selection, ingestion, and absorption in filter-feeding bivalves. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 91:77–92

Smith KA, North EW, Shi FY et al (2009) Modeling the effects of oyster reefs and breakwaters on seagrass growth. Estuar Coast 32:748–757

Soniat TM, Finelli CM, Ruiz JT (2004) Vertical structure and predator refuge mediate oyster reef development and community dynamics. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 310:163–182

Stafford J (1913) The Canadian oyster. Its development, environment and culture. The Mortimer Co. Ltd., Ottawa

Stafford J (1915) The native oyster of British Columbia. Report of the British Columbia Commission of Fisheries, pp 141–160

Steele EN (1957) The rise and decline of the Olympia oyster. Fulco Publications, Elma

Stenzel HB (1971) Oysters. In: Moore RC (ed) Treatise on invertebrate paleontology, part N. University of Kansas Press, Kansas, pp 953–1224

Uncles RJ, Stephens JA, Smith RE (2002) The dependence of estuarine turbidity on tidal intrusion length, tidal range and residence time. Cont Shelf Res 22:1835–1856

Wagner E, Dumbauld BR, Hacker SD, Trimble AC, Wisehart LM, Ruesink JL (2012) Density-dependent effects of an introduced oyster, Crassostrea gigas, on a native intertidal seagrass, Zostera marina. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 468:149–160

Wall CC, Peterson BJ, Gobler CJ (2008) Facilitation of seagrass Zostera marina productivity by suspension-feeding bivalves. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 357:165–174

Walne PR (1972) The influence of current speed, body size and water temperature on the filtration rate of five species of bivalves. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 52:345–374

White JM, Ruesink JL, Trimble AC (2009) The nearly forgotten oyster: Ostrea lurida Carpenter 1864 (Olympia oyster) history and management in Washington State. J Shellfish Res 28:43–49

Wilson JH (1983) Retention efficiency and pumping rate of Ostrea edulis in suspensions of Isochrysis galbana. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 12:51–58

zu Ermgassen PSE, Spalding MD, Blake B, Coen LD, Dumbauld B, Geiger S, Grabowski JH, Grizzle R, Luckenbach M, McGraw KA, Rodney B, Ruesink JL, Powers SP, Brumbaugh RD (2012) Historical ecology with real numbers: past and present extent and biomass of an imperilled estuarine ecosystem. Proc R Soc B 279:3393–3400. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0313

zu Ermgassen PSE, Spalding MD, Grizzle RE, Brumbaugh RD (2013) Quantifying the loss of a marine ecosystem service: filtration by the eastern oyster in U.S. estuaries. Estuar Coast 36:36–43. doi:10.1007/s12237-012-9559-y

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Partnership between The Nature Conservancy and NOAA’s Community-based Restoration Program (Award Nos. NA07NMF4630136 and NA10NMF463008). Additional funding support for the project was provided by the TNC-Shell Partnership and The Turner Foundation, Inc. MWG and CJL would like to thank National Estuarine Research Reserve System, NOAA (Award No. NA10NOS4200025) for funding the filtration rate experiments, and the Molluscan Broodstock Program staff for providing seawater, algae, and laboratory assistance. The authors would like to thank Dr. Jonathan Gair for assistance with model fitting, and an anonymous reviewer for comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handling Editor: Piet Spaak.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

zu Ermgassen, P.S.E., Gray, M.W., Langdon, C.J. et al. Quantifying the historic contribution of Olympia oysters to filtration in Pacific Coast (USA) estuaries and the implications for restoration objectives. Aquat Ecol 47, 149–161 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10452-013-9431-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10452-013-9431-6