Abstract

Background and Objectives

To describe laparoscopic management of adnexal mass during pregnancy between January 1994 and November 2003 and give an overview of existing literature on this subject (1992–2003).

Design

Observational (descriptive) study with prospectively collected database supplemented by retrospective chart review.

Setting

Tertiary-care referral centre.

Subjects

Eleven consecutive pregnant patients with an adnexal mass.

Interventions

Ten patients had laparoscopy with the open entry technique and one with the closed entry technique.

Main outcome measures

Blood loss, operating time, number of conversions to laparotomy, complications and pregnancy outcome.

Results

The incidence of laparoscopic management of adnexal pathology during pregnancy in our institution was 1:1,206 pregnancies (0.1%). One patient was suspected to have an ovarian malignancy, which appeared to be a large malignant tumour originating from the intestine. Ovarian malignancy was not found. In seven cases, surgery was postponed until the 16th week of gestation; however, four patients required surgery earlier in pregnancy due to suspicion of ovarian malignancy (n=1) or adnexal torsion (n=3). No entry-related or intra-operative complications occurred. Two procedures were converted to laparotomy but were not due to laparoscopic complications. One intra-uterine foetal death occurred at 24 weeks of gestation (12 weeks after adnexal detorsion). No postoperative maternal complications occurred, and nine healthy infants were born. One patient continues to have an uncomplicated pregnancy.

Conclusions

Adnexal masses requiring surgical intervention can be explored laparoscopically. We advise the open entry technique in order to avoid entry-related complications, e.g. to the pregnant woman’s uterus and the adnexal mass.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reported incidence of adnexal masses during pregnancy ranges from 1:81 to 1 in 2,500, with an overall rate of malignancy of 2–5% [1]. Management of these masses during pregnancy presents a clinical dilemma. Abdominal surgery during gestation brings risk to both mother and foetus. However, conservative management may result in torsion, rupture of the mass, obstruction during delivery [2] or metastases in cases of malignancy [1]. Therefore, in some cases surgical intervention is necessary.

Small cysts early in pregnancy are most likely to be functional, and conservative management is preferable. However, some masses persist or even grow during pregnancy without any complaints. In order for the potential risks of a surgical emergency to be avoided, elective removal is recommended in the case of an adnexal mass larger than 6 cm that persists after 16 weeks of gestation [2, 3]. Elective removal is suggested to result in less morbidity than in an emergency setting [3]. Also, in the case of malignant features at ultrasound, surgical intervention is required [1].

It has been suggested that the laparoscopic approach can safely be performed during pregnancy [1, 4, 5]. However, one study of seven patients in a general surgical emergency setting reported a high rate of foetal death (57%) [6]. The advantages of a laparoscopic approach compared with laparotomy include lower prevalence of operating complications, less postoperative pain, quicker resumption of normal bowel function, short hospital stay and less adhesion formation [1, 7, 8]. Above all, a rapid recovery reduces surgery-related complications such as thromboembolism, the leading cause of maternal death [9, 10]. Incisional herniation as a late complication is rarely seen [11]. On the other hand, the pneumoperitoneum may cause potential risk to the foetus. Increased abdominal pressure may lead to decreased uterine blood flow, premature contractility or premature labour [12]. Also, the effect of carbon dioxide on the foetus during laparoscopy is not well understood. However, animal studies suggest that there are no deleterious effects of the latter [13].

In contrast to general surgery [12], in gynaecology no guidelines concerning the laparoscopic approach during pregnancy are available. General surgeons’ published data suggest that the open laparoscopic entry technique is preferred in pregnancy so that entry-related complications can be avoided [12]. This possibly reduces the risk of penetrating injury to the uterus by either by Veress needle or first trocar. Adnexal masses during pregnancy, which require surgery, are relatively rare, which makes randomisation for either entry technique hardly feasible. Until the results of a randomised study are published, we will continue to be confronted with the clinical dilemma of pregnant patients with adnexal masses, which makes case series valuable [14]. For this reason we describe our laparoscopic experience of adnexal masses during pregnancy, with special attention to the laparoscopic approach.

Material and methods

All pregnant women with an adnexal mass requiring surgery at the Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC) between January 1994 and November 2003 were included in the study. If no additional malignant features (e.g. ascites or omental cake) were found at ultrasound and clinical examination, the adnexal masses were explored laparoscopically. Depending on the intra-operative findings we decided whether to proceed laparoscopically or to convert to laparotomy. Patients were preferably operated upon after 16 weeks of gestation. Figure 1 shows our pre-operative and intra-operative management technique in cases where an adnexal mass was found that required surgical intervention. Criteria for cystectomy or adnexectomy were the same as for non-pregnant women of reproductive age. Cystectomy was performed whenever possible so that ovarian tissue would be preserved.

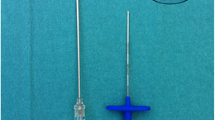

All women had a documented intra-uterine pregnancy. All laparoscopic procedures were preferably performed with the open laparoscopic entry technique as first described by Hasson [15]. We modified this technique by introducing the Origin balloon trocar (Autosuture) with blunt tip, after the abdomen had been opened, via a 2 to 3-cm transverse incision beneath the umbilicus. Pneumoperitoneum was established under direct vision of the laparoscope. Data on patients were collected by a prospectively kept database supplemented by a retrospective chart review. Age, gestational age, gravity, parity, symptoms, size of the mass, operating time and technique, estimated blood loss, complications, use of tocolysis, histopathology, length of hospital stay and postoperative course, including pregnancy outcome, were recorded. Serum CA-125 determination was not routinely performed.

We routinely performed gastric and bladder decompression with a nasogastric tube and a Foley catheter prior to gaining access to the abdominal cavity. All laparoscopic procedures were performed under endotracheal anaesthesia. The intra-abdominal CO2 insufflation pressure was automatically regulated and maintained at 12–14 mmHg. All masses were extracted with an Endo-bag (Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany). No cervical devices were used for manipulation of the uterus during the procedure. Postoperatively, the foetal heart tones and uterine contractility were checked. Prophylactic tocolysis was not routinely given. Recently, the protocol in our clinic has been adjusted, since the use of prophylactic tocolysis is shown to be ineffective [1, 16]. Gynaecologists experienced in laparoscopic surgery performed the procedure.

Outcome measures were: blood loss during the procedure, operating time, number of conversions to laparotomy, intra-operative and postoperative complications and pregnancy outcome.

Results

Eleven consecutive pregnant patients had a laparoscopic procedure during this period. No primary laparotomies were performed for adnexal masses in pregnancy during this time. The incidence of surgery for adnexal masses during pregnancy in our institution was 1:1,206 pregnancies (0.1%). Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics. Mean age was 29 years (range 21–37 years). In five patients the adnexal mass was found at routine ultrasound for estimation of gestational age, three patients had an ultrasound examination for vaginal blood loss, and three patients presented with an acute abdomen suspicious of a tordated adnex.

Seven patients underwent cystectomy, two patients adnexectomy, one patient unwinding of a twisted adnex combined with drainage of the cyst and one patient underwent debulking of a large gastrointestinal tumour. Two procedures were converted to laparotomy (case nos. 7 and 8). In case no. 7 the diameter of the ovarian cyst, with a macroscopic benign aspect, was too large for an Endo-bag to be used. A small laparotomy by median incision was performed so that possible spillage of cystic content could be prevented. Based on this laparoscopic finding the incision of the laparotomy was smaller than it would have been in a primary laparotomy. In case 8 the pelvic mass was difficult for us to interpret at ultrasound. Ultrasonic aspects were of a benign ovarian cyst. Laparoscopy revealed normal ovaries and a large tumour originating from the intestine. The procedure was converted to a median laparotomy, and general surgeons performed a debulking of the tumour. A histopathological specimen revealed a gastrointestinal stroma-cell tumour.

Four of the 11 patients had surgery before the 16th week of gestation (case nos. 4, 7, 10 and 11). Indication in three patients was acute abdomen (case nos. 4, 10 and 11); in the fourth patient the adnexal mass was suspected of being malignant, on ultrasound (case no. 7). However, in this case no additional malignant features were seen on ultrasound. To decide where and how to place the incision of the laparotomy, we performed a diagnostic laparoscopy. Of these four patients, two had functional cysts (case nos. 4 and 7).

In one patient (case no. 9) surgery could be postponed until the 16th week of gestation, and a functional cyst was removed.

Four of 11 patients received prophylactic tocolysis. Mean blood loss during laparoscopic surgery was100 ml (25–300 ml) and for laparotomy was 100 and 6,000 ml. In this study laparoscopic cystectomy took an average time of 76 min, laparoscopic adnexectomy lasted for 70 min. Postoperative hospital stay varied from 1 to 22 days, with a mean stay after laparoscopic surgery of 2.1 days and, for laparotomy, 6 and 22 days.

One adverse foetal outcome occurred (case no. 4). An intra-uterine foetal death (IUFD) was diagnosed at 24 weeks of gestation, 12 weeks after laparoscopy in an emergency setting. Autopsy gave no explanation for the death. Nine women delivered healthy babies at term. No intra-operative complications occurred. One patient (case no. 11) has an ongoing uncomplicated pregnancy.

In Table 2 an overview of gynaecological laparoscopy (approximately 210 cases) during pregnancy is given.

Discussion

Conservative management of a symptom-free adnexal mass with a benign aspect on ultrasound examination can be justified until the 16th week of gestation for two reasons. First, it is stated that an adnexal mass before the 16th week of gestation is often a functional cyst and the incidence of these cysts after 16 weeks is minimal [1, 3]. However, in our series one patient still had a persistent functional cyst after this period (case no. 9). Second, we have to consider the direct risk of surgery to the foetus early in pregnancy. Surgery is thought to be related to an increased risk of spontaneous abortion. Although laparoscopy in the third trimester has been described by some authors, it causes technical difficulties due to the enlarged uterus (Table 2) [17, 18]. Therefore, in our opinion, if laparoscopy is necessary, the second trimester seems to be the optimum period for surgery to be performed.

In our opinion, even in cases with suspicion of a malignant adnexal mass without additional features of malignancy on ultrasound (e.g. ascites, omental cake), a primary diagnostic laparoscopy is mandatory (Fig. 1) [19]. The peritoneal cavity and pelvic mass can be inspected for macroscopic malignant features. The advantage of this sequence is that origin, location and size of the pelvic mass can be determined. If the surgeon decides to convert to laparotomy, the location and size of the incision can be adjusted to the laparoscopic findings (case no. 7) [20]. However, in this context, we have to consider that, even in experienced hands, for macroscopic qualification of an adnexal mass the false-positive findings for malignancy were as high as 53% [21]. Additional to ultrasound, in case of uncertainty of the origin of the mass, pre-operative MRI can give additional information [22].

Determination of CA-125 as a predictor of ovarian malignancy is shown not to be useful in pregnancy [23], since its level is frequently elevated in normal pregnancy. CA-125 has a low specificity (69%), which leads to many false positive findings (22%) [23].

A major concern with regard to laparoscopic procedures during pregnancy is the initial insertion of the Veress needle and the first trocar. In contrast to general surgery [12], in gynaecology no official guidelines are available concerning the laparoscopic approach during pregnancy. General surgeons’ published data suggest that the open laparoscopic entry technique is preferred in pregnancy so that entry-related complications may be avoided [12]. Although the closed entry technique in gynaecology should not be abandoned [24], in the case of pregnancy we advocate the use of the open entry technique. Although our series do not give enough evidence to support the abandoning of the closed entry technique in pregnancy, we have to bear in mind that an ovarian cyst, when located in the pouch of Douglas, can lift the uterus and increase the chance of injury by the sharp instruments. In addition, the risk of penetration of the adnexal mass during the closed entry technique is possible, with the adverse effect of spillage of cystic content [25]. However, a closed entry technique can be considered when the size of the pelvic mass is less than 12 weeks of gestation. In our series no entry-related complications for either entry technique was experienced.

When feasible, if the patient is of reproductive age we recommend ovarian cystectomy, both in pregnant and non-pregnant women, to preserve ovarian tissue. Unfortunately, in case no. 6 cystectomy was not feasible, due to adhesions, and ovarian tissue could not be spared.

In this study the mean duration of laparoscopic cystectomy was 76 min and that of laparoscopic adnexectomy was 70 min. Neither procedure is more time consuming. Performing cystectomy in pregnant patients, we encountered no difficulties or excessive blood loss.

Four patients received prophylactic tocolytic agents. Nowadays, the routine use of prophylactic tocolysis is shown to be ineffective [1, 16], thus, in our clinic, tocolysis is given only to patients who are suffering from postoperative uterine irritability, in contrast to the practice by Mathevet et al. [5].

An adnexal mass during pregnancy that requires surgery is a relatively rare phenomenon and is still a dilemma for clinicians. Although reports of small series on this subject are published (approximately 210 cases) it is still important for more data and evidence to be collected in order for this problem to be treated optimally. We have to consider that, for many reasons, e.g. surgeons’ experience and preferences, it is difficult for one to carry out randomised prospective studies for surgical evaluation [26].

Our algorithm in Fig. 1 shows how we support the guidelines of general surgeons in performing open laparoscopy in pregnant women in order to avoid entry-related complications to the uterus and adnexal mass.

References

Fatum M, Rojansky N (2001) Laparoscopic surgery during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv 56:50–59

Struyk AP, Treffers PE (1984) Ovarian tumors in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 63:421–424

Hess L, Peaceman A (1988) Adnexal mass occurring with intrauterine pregnancy: report of fifty-four patients requiring laparotomy for definitive management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 158:1029–1034

Parker WH, Childers JM (1996) Laparoscopic management of benign cystic teratomas during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 174:1499–1501

Mathevet P, Nessah K, Dargent D, Mellier G (2003) Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses in pregnancy: a case series. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 108:217–222

Amos JD, Schorr SJ, Norman PF (1996) Laparoscopic surgery during pregnancy. Am J Surg 171:435–437

Oelsner G, Stockheim D, Soriano D, Goldenberg M, Seidman DS, Cohen SB, et al (2003) Pregnancy outcome after laparoscopy or laparotomy in pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 10:200–204

Pittaway DE, Takacs P, Bauguess P (1994) Laparoscopic adnexectomy: a comparison with laparotomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 171:385–391

Soriano D, Yefet Y, Seidman DS (1999) Laparoscopy versus laparotomy in the management of adnexal masses during pregnancy. Fertil Steril 71:955–960

Andreoli M, Servako M, Meyers P, Mann WJ (1999) Laparoscopic surgery during pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 6:229–233

Lemaire BM, van Erp WF (1997) Laparoscopic surgery during pregnancy. Surg Endosc 11:15–18

SAGES (1998) Guidelines for laparoscopic surgery during pregnancy. Surg Endosc 12:189–190

Bernard J, Chaffin D, Droste S, Tierney A, Phernetton T (1995) Fetal response to carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum in the pregnant ewe. Obstet Gynecol 85:669–674

Vandenbroucke JP (2001) In defence of case reports and case series. Ann Intern Med 134:330–334

Hasson HM (1971) A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 110:886–887

Kort B, Katz VL (1993) The effect of nonobstetric operation during pregnancy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 177:371–376

Kim WW, Chon JY, Chun SW, Jeon HM, Kim EK (2000) Laparoscopic procedures during the third trimester of pregnancy. Surg Endosc 14:501

Bassil S, Steinhart U, Donnez J (1999) Successful laparoscopic management of adnexal torsion during week 25 of twin pregnancy. Hum Reprod 14:855–857

Timmerman D, Bourne TH (1999) A comparison of methods for preoperative discrimination between malignant and benign adnexal masses: the development of a new logistic regression model. Am J Obstet Gynecol 181:57–65

Bonjer HJ, Hazebroek EJ, Kazemier G, Giuffrida MC, Meijer WS, Lange JF (1997) Open versus closed establishment of pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic surgery. Br J Surg 84:599–602

Nezhat F, Nezhat C (1992) Four ovarian cancers diagnosed during laparoscopic management of 1011 women with adnexal masses. Am J Obstet Gynecol 167:790–796

Edwards RK, Ripley DL (2001) Surgery in the pregnant patient. Curr Probl Surg 38:213–290

Finkler NJ, Benacerraf B (1988) Comparison of serum CA 125, clinical impression, and ultrasound in the preoperative evaluation of ovarian masses. Obstet Gynecol 72:659–664

Chapron C, Cravello L, Chopin N, Kreiker G, Blanc B, Dubuisson JB (2003) Complications during set-up procedures for laparoscopy in gynecology: open laparoscopy does not reduce the risk of major complications. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 82:1125–1129

Vergote I, De Brabanter J, Fyles A, Bertelsen K, Einhorn N, Sevelda P, et al (2001) Prognostic importance of degree of differentiation and cyst rupture in stage I invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Lancet 357:176–182

Allen JR, Hellings TS, Langerfeld M (1989) Intra-abdominal surgery during pregnancy. Am J Surg 158:567–569

Guerrieri JP, Thomas RL (1994) Open laparoscopy for an adnexal mass in pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med 39:129–130

Howard FM, Vill M (1994) Laparoscopic adnexal surgery during pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2:91–3

Levy T, Dicker D, Shalev J, et al (1995) Laparoscopic unwinding of hyperstimulated ischemic ovaries during the second trimester of pregnancy. Hum Reprod 10:1478–1480

Tazuke S, Nezhat CR, Phillips DR, Roemisch M (1996) Removal of adnexal masses by operative laparoscopy during pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 3:S50

Neiswender LL, Toub DB (1997) Laparoscopic excision of pelvic masses during pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 4:269–272

Morice P, Christine LS, Chapron C, et al (1997) Laparoscopy for adnexal torsion in pregnant women. J Reprod Med 42:435–439

Nezhat FR, Tazuke S, Nezhat CH, et al (1997) Laparoscopy during pregnancy. A literature review. J Soc Laparoendosc Surg 1:17–27

Yuen PM, Chang AMZ (1997) Laparoscopic management of adnexal mass during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 76:173–176

Moore RD, Smith WG (1999) Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses in pregnant women. J Reprod Med 44:97–100

Mattei A (1999) Laparoscopic removal of benign uterine and adnexal masses during pregnancy. Gynecol Endosc 8:21–23

Abu-Musa A, Nassar A, Usta I, Khalil A, Hussein M(2001) Laparoscopic unwinding and cystectomy of twisted dermoid during second trimester of pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 8:456–460

Stepp KJ, Tulikangas PK, Goldberg JM, Attaran M, Falcone T (2003) Laparoscopy for adnexal masses in the second trimester of pregnancy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 10:55–59

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kolkman, W., Scherjon, S.A., Gaarenstroom, K.N. et al. Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses with the open entry technique in second-trimester pregnancy. Gynecol Surg 1, 21–25 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10397-004-0007-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10397-004-0007-2