Abstract

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) provides high spatial and contrast resolution and is a useful tool for evaluating the pancreato-biliary regions. Recently, contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS (CH-EUS) has been used to evaluate lesion vascularity, especially for the diagnosis of pancreatic tumors. CH-EUS adds two major advantages when diagnosing pancreatic cystic lesions (PCL). First, it can differentiate between mural nodules and mucous clots, thereby improving the accurate classification of PCL. Second, it helps with evaluation of the malignant potential of PCL, especially of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms by revealing the vascularity in the mural nodules and solid components. This review discusses the use and limitations of CH-EUS for the diagnosis of PCL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

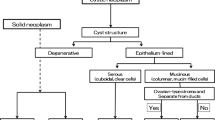

Pancreatic cystic lesions (PCL) include various types of cysts. They are classified as inflammatory cysts, neoplastic cysts, or simple cysts. The most commonly encountered cystic lesions in daily clinical practice are pancreatic cystic neoplasms, especially intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN). In addition to IPMN, pancreatic cystic neoplasms comprise mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCN), serous neoplasms (SN), cystic degenerative lesions of solid tumors, such as solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPN), pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PanNEN), cystic lesions associated with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), and more. For each tumor, the differential diagnosis is based on the imaging findings of CT, MRI, and EUS, and it is essential to understand the characteristics of the different types of PCL (Table 1). Contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS (CH-EUS) can detect the presence or absence of microvessels and monitor dynamic changes in contrast patterns in the region of interest (ROI). CH-EUS has been used in the diagnosis of pancreatic lesions [1, 2]. The aim of this article is to review the current evidence on the utility of CH-EUS for the diagnosis of PCL.

History of CE-EUS for the diagnosis of pancreato-biliary lesions

Historically, CE-EUS was first applied to visualize blood flow signals using color Doppler mode. In 1995, Kato et al. reported a technique for capturing enhanced ultrasound images by injecting CO2 microbubbles under angiography [3]. In 1998, the usefulness of CE-EUS using a transvenous contrast agent called Albunex® was reported for diagnosing pancreatic disease [4]. Since then, following developments in ultrasound observation systems and ultrasound contrast agents, especially the contrast-enhanced harmonic method, in which microcirculation in the lesion is observed using harmonic images, has become the main CE-EUS method (Fig. 1). Use of the contrast-enhanced harmonic method reduces artifacts, such as blooming, which is a problem with the color Doppler method, and enables observation of fine blood flow in vessels and tissues. Therefore, CH-EUS contributes to a better qualitative and quantitative evaluation of lesions in several organs [5].

Outline of use of CH-EUS for the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions

EUS observation from the stomach and duodenum allows close-up evaluation of the pancreas. PCL can be formed by various causes and pathogenesis, including neoplastic lesions, cystic lesions caused by inflammation, and simple cysts or congenital cysts. In recent years, Kromrey et al. found using magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatgraphy (MRCP) that about half of the elderly have pancreatic cystic lesions [6]. Important for the differential diagnosis of PCL are their size, localization, shape of the cyst (unilocular or multilocular), and their connections with pancreatic ducts. Furthermore, critical for evaluating the malignant potential of PCL are the dynamic changes over time of the size of the cyst and/or the diameter of the main pancreatic duct (MPD), whether the cyst carries mural nodules or a solid component within, and whether there is a solid mass lesion or pancreatic stone surrounding the cyst [7]. CH-EUS can clearly demonstrate the difference between mural nodules and mucus clots within the cyst in terms of blood flow in the target lesion. Use of contrast agents improves the contrast resolution, thereby clarifying structures such as low papillary lesions or thickness of the septum in the cyst, or low papillary lesions on the MPD [8, 9]. When a solid component is identified in or beside a PCL, the enhancement patterns determined by CH-EUS can be useful for differentiating between IPMN-derived cancer and invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [10].

Specific findings and current evidence

Usefulness of CH-EUS in the differential diagnosis of PCL

EUS is an imaging method with high spatial resolution in comparison with cross-sectional imaging such as CT or MRI [5, 11]. The key points of observation with EUS for the differential diagnosis of PCL consist of (i) the size of the cyst, (ii) the shape of the cyst (unilocular or multilocular), (iii) the presence or absence of a connection with the MPD, (iv) the internal structure of the cyst (presence/absence of mural nodules, septum, and mucus clots), and (v) the pancreatic parenchyma surrounding the cyst. CE-EUS (including CH-EUS) can improve the recognition of pancreatic cyst structures, both in terms of increasing the contrast resolution and excluding the non-contrast structures, such as mucus clots.

Hirooka et al., in 1998, reported the usefulness of CE-EUS with the early generation of ultrasound contrast agents in the differential diagnosis of PCL [4]. In that report, they noted contrast-enhancing nodule-like lesions within mucus-producing and serous cystic tumors, whereas no contrast-enhancing structures were found within pancreatic pseudocysts. Thus, CE-EUS is useful for excluding non-neoplastic structures such as mucus clots or protein plugs within cysts (Figs. 2, 3). Three other studies using CH-EUS also recognized the importance of the diagnosis of a contrast-enhanced nodular component within cysts for differentiating neoplastic pancreatic cysts from pseudocysts [12,13,14]. In a prospective study comparing the diagnostic performance for PCL, Zhong et al. reported that CH-EUS demonstrated greater accuracy in identifying PCL than contrast-enhanced CT, MRI, and fundamental B-mode EUS (FB-EUS) (CE-EUS vs. CT: 92.3% vs. 76.9%; CE-EUS vs. MRI: 93.0% vs. 78.9%; CE-EUS vs. FB-EUS: 92.7% vs. 84.2%) [15]. However, the qualitative differential diagnosis between PCL types remains mainly based on the structure of the cysts on conventional B-mode ultrasound, and the additional value of CH-EUS may be limited [12,13,14].

Utility of CH-EUS for the diagnosis of mural nodules in mucin-producing pancreatic cystic tumors (IPMN and MCN)

There are 15 reports on the usefulness of CE-EUS including CH-EUS for the diagnosis of mural nodules in pancreatic cystic tumors, mainly in IPMN [5, 8,9,10, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. One meta-analysis reported that the presence of a mural nodule diagnosed using CE-EUS was an independent predictor for the diagnosis of malignant IPMN. In addition, guidelines that evaluated the usefulness of CH-EUS reported that the presence of a mural nodule or solid component was important for the diagnosis of malignant lesions in cystic tumors of the pancreas [5]. For examples of the use of CH-EUS, see Fig. 4 and Video 1: Supplementary File.

Harima et al. reported that CH-EUS had a higher ability to diagnose mural nodules than other diagnostic methods such as contrast-enhanced CT or conventional B-mode EUS [16]. Yamashita et al. compared the diagnostic performance of preoperative CE-CT, conventional EUS, and CH-EUS. The sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for detection of mural nodules using pathological diagnosis as the reference standard were 70%, 76%, and 72%, respectively, for CE-CT; 97%, 36%, and 83%, respectively, for conventional EUS; and 97%, 76%, and 92%, respectively, for CH-EUS. Conventional EUS and CH-EUS were significantly superior to CE-CT for detecting mural nodules (p = 0.003 and p < 0.001, respectively). This study concluded that CH-EUS was the most accurate modality for detecting mural nodules [21].

Ohno et al. defined MNs as protruding components with a blood flow signal confirmed on CE-EUS. They classified MNs into four types based on their morphology: type I (low papillary nodule) was defined as low, fine, protruding components in the cyst wall or MPD epithelium (Fig. 5a); type II (polypoid nodule) as a smooth-surfaced component protruding into the cyst or MPD (Fig. 5b); type III (papillary nodule) as a protruding component with a thickened cyst wall or MPD epithelium or with an irregular, villous structure (Fig. 5c); and type IV (invasive nodule) as a lesion in which papillary nodules are connected to a hypoechoic area ill-defined from the pancreatic parenchyma (Fig. 5d). The rate of malignancy was 25% in type I, 40% in type II, 88.9% in type III, and 91.7% in type IV. They reported that type III and IV MNs were associated with malignancy [8]. Yamamoto et al. [17] evaluated the serial changes in the enhancement pattern in mural nodules using time intensity curve (TIC) analysis. In their report, the rate of attenuation of contrast effect, and the ratio of contrast effect between the nodule and normal parenchyma, were significantly higher in malignant lesions [17].

a Type I mural nodule (low papillary nodule) on CH-EUS. The right image is the contrast-enhanced harmonic mode. A low papillary fine protruding lesion is shown in the cyst wall (arrow head). b Type II mural nodule (polypoid nodule) on CH-EUS. The right image is the contrast-enhanced harmonic mode. A polypoid lesion with smooth surface is shown in the cyst wall (arrow head). c Type III mural nodule (papillary nodule) on CH-EUS. The left image is the contrast-enhanced harmonic mode. A relatively large villous protruding lesion is shown in the cyst wall (arrow head). d Type IV mural nodule (invasive nodule) on CH-EUS. The right image is the contrast-enhanced harmonic mode. A hypoechoic mass lesion ill-defined from the pancreatic parenchyma is connected with a papillary lesion in the cyst

Ohno et al. [9] reported the diagnostic ability of CH-EUS for the pathological localization or distribution of low-papillary lesions into the main pancreatic duct (MPD involvement). In that study, the findings of “MPD involvement” in the diagnosis of IPMN were classified into two types: one was based on the localization or distribution of low-papillary lesions in the MPD on CH-EUS, and the other was based on the diameter of the MPD on CT or MRI. As a result, the “MPD involvement” diagnosed based on low-papillary lesions on CH-EUS showed a significantly higher diagnostic accuracy than that based on MPD diameter [9].

The current gold standards for diagnosis of mural nodules according to the international consensus guidelines for IPMN (Revised Fukuoka Guideline) are contrast-enhanced CT and contrast-enhanced MRI in terms of contrast-enhancement [18]. EUS diagnosis, especially imaging using CH-EUS, is expected to become as important as CT and MRI in determining the treatment strategy for IPMN.

Use of CH-EUS in the management of IPMN, and their differentiation from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDAC)

CH-EUS has mainly been used in the diagnosis of pancreatic solid lesions including qualitative and quantitative assessments using TIC analysis [19, 20].

Yamashita et al. reported that the pattern of early washout observed on CH-EUS showed high diagnostic performance in identifying malignant IPMN, especially in patients with invasive IPMC, with a sensitivity of 58%, specificity of 100%, and accuracy of 86% [21].

Yashika et al. [10] compared contrast patterns between IPMN-derived invasive carcinoma and conventional PDAC using a multiphasic evaluation method. They found that IPMN-derived invasive carcinoma tend to have a longer-lasting contrast effect than conventional pancreatic ductal carcinoma, and that the enhancement pattern of IPMN-derived invasive carcinoma was different from that of conventional pancreatic cancer. Therefore, they proposed the possibility of predicting the histological type of the entire lesion, especially in cases of unresectable pancreatic cancer [10].

Conclusion

EUS provides detailed, highly sensitive images, and CH-EUS is a useful method for evaluating mural nodules and solid components when diagnosing PCL.

Change history

13 March 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10396-024-01431-1

References

Kitano M, Sakamoto H, Matsui U, et al. A novel perfusion imaging technique of the pancreas: contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:141–50.

Kitano M, Kamata K, Imai H, et al. Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography for pancreatobiliary diseases. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:60–7.

Kato T, Tsukamoto Y, Naitoh Y, et al. Ultrasonographic and endoscopic ultrasonographic angiography in pancreatic mass lesions. Acta Radiol. 1995;36:381–7.

Hirooka Y, Goto H, Ito A, et al. Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography in pancreatic diseases: a preliminary study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:632–5.

Kitano M, Yamashita Y, Kamata K, et al. The Asian Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (AFSUMB) guidelines for contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2021;47:1433–47.

Kromrey ML, Bülow R, Hübner J, et al. Prospective study on the incidence, prevalence and 5-year pancreatic-related mortality of pancreatic cysts in a population-based study. Gut. 2018;67:138–45.

Ohno E, Ishikawa T, Mizutani Y, et al. Factors associated with misdiagnosis of preoperative endoscopic ultrasound in patients with pancreatic cystic neoplasms undergoing surgical resection. J Med Ultrason. 2022;49:433–41.

Ohno E, Hirooka Y, Itoh A, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: differentiation of malignant and benign tumors by endoscopic ultrasound findings of mural nodules. Ann Surg. 2009;249:628–34.

Ohno E, Kawashima H, Ishikawa T, et al. Can contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography accurately diagnose main pancreatic duct involvement in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms? Pancreatology. 2020;20:887–94.

Yashika J, Ohno E, Ishikawa T, et al. Utility of multiphase contrast enhancement patterns on CEH-EUS for the differential diagnosis of IPMN-derived and conventional pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2021;21:390–6.

Ohno E, Hirooka Y, Kawashima H, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography for the evaluation of pancreatic cystic neoplasms. J Med Ultrason. 2020;47:401–11.

Kamata K, Kitano M, Omoto S, et al. Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography for differential diagnosis of pancreatic cysts. Endoscopy. 2016;48:35–41.

Fusaroli P, Serrani M, De Giorgio R, et al. Contrast harmonic-endoscopic ultrasound is useful to identify neoplastic features of pancreatic cysts (with videos). Pancreas. 2016;45:265–8.

Hocke M, Cui XW, Domagk D, et al. Pancreatic cystic lesions: the value of contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound to influence the clinical pathway. Endosc Ultrasound. 2014;3:123–30.

Zhong L, Chai N, Linghu E, et al. A prospective study on contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound for differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:3616–22.

Harima H, Kaino S, Shinoda S, et al. Differential diagnosis of benign and malignant branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm using contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6252–60.

Yamamoto N, Kato H, Tomoda T, et al. Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography with time-intensity curve analysis for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Endoscopy. 2016;48:26–34.

Tanaka M, Fernández-Del Castillo C, Kamisawa T, et al. Revisions of international consensus Fukuoka guidelines for the management of IPMN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2017;17:738–53.

Matsubara H, Itoh A, Kawashima H, et al. Dynamic quantitative evaluation of contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis of pancreatic diseases. Pancreas. 2011;40:1073–9.

Ishikawa T, Hirooka Y, Kawashima H, et al. Multiphase evaluation of contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis of pancreatic solid lesions. Pancreatology. 2018;18:291–7.

Yamashita Y, Kawaji Y, Shimokawa T, et al. Usefulness of contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography for diagnosis of malignancy in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:2141.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Ethical statement

As this is a review article based on published literature, no ethics approval was required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised due to a retrospective open access order.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Supplementary File: Video 1 A case of IPMN. CH-EUS shows the non-enhanced hypoechoic area in a cyst. CH-EUS can clearly distinguish mural nodules from mucous clots. (MP4 39409 KB)

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohno, E., Kuzuya, T., Kawabe, N. et al. Use of contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography for the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. J Med Ultrasonics (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10396-023-01376-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10396-023-01376-x