Abstract

Aim

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a major impact on migrants and ethnic minority (MEM) populations in terms of risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, morbidity, and mortality. The aim of this study is to investigate inequalities accessing healthcare for COVID-19 among MEM populations compared to the general population.

Subject and methods

A systematic review was conducted, collecting studies on MEM populations’ access to healthcare for COVID-19 in the WHO European region in terms of access to prevention, diagnosis, and care, published from January 2020 to February 2022, on the following databases: Medline, Embase, Biosis, Scisearch, and Esbiobase.

Results

Of the 19 studies identified, 11 were about vaccine hesitancy, five about vaccine execution, two about access to COVID-19 testing, and one was about access to information on COVID-19. Twelve studies were conducted in the UK. Overall, MEM populations faced greater barriers to accessing vaccination, turned out to be more vaccine hesitant, and faced more difficulties in accessing COVID-19 information and testing.

Conclusion

These findings highlight the inequalities MEM populations faced accessing healthcare services for COVID-19 and health information. There is the need for policymakers to prioritize strategies for building trust and engage MEM populations to overcome the barriers when designing health promotion and care programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

With more than 760 million infected globally and more than 6.9 million deaths at the time of writing (WHO 2023), the COVID-19 pandemic has affected populations worldwide. It is widely recognized that the pandemic has had a greater impact on lower socioeconomic groups and minorities (Burstrom and Tao 2020) so that, for the most disadvantaged communities, COVID-19 is experienced as a syndemic, a co-occurring, synergistic pandemic that interacts with and exacerbates their poor social status (Bambra et al. 2020). This is particularly true for migrants and ethnic minority (MEM) populations, since they frequently live in poor conditions and experience great economic precarity (Orcutt et al. 2020), while health protections and reliable social support are often not easily accessible (Abubakar et al. 2018). Several studies (Chadeau-Hyam et al. 2020; Rao et al. 2021; Raisi-Estabragh et al. 2020; Williamson et al. 2020) already reported that MEM populations experienced a higher burden both in terms of risk of infection and negative health outcomes from COVID-19. This is partly due to the difficulty accessing health information and healthcare services: before the pandemic a report published by the European Social Policy Network (ESPN) (European Commission et al. 2018) explored inequalities accessing healthcare in European countries and concluded that important disparity persists both between and within countries, particularly for vulnerable groups. Access to healthcare can be hindered by residence status, ethnicity, and migratory background (Marceca 2017).

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the vaccine campaign has played a key role in controlling the spreading of SARS-CoV-2 and in reducing the related hospitalizations and deaths. For this reason, accessibility to vaccines is of great importance. People approaching healthcare can face barriers to vaccination that can be both structural and attitudinal; structural barriers are systemic issues that may limit the ability of the individuals to access the service, while attitudinal barriers are beliefs or perceptions that may reduce one’s willingness to seek out or accept a vaccine service (Fisk 2021).

While many witnessed that, during the pandemic of COVID-19, MEM populations had greater difficulties in accessing healthcare services, systematic scientific evidence of this phenomenon is lacking, especially in the WHO European region, where about 90 million international migrants are living, amounting to almost 10% of the total population (World Health Organization and Regional Office for Europe 2018).

This review is the third of a three-systematic review project designed to assess the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on MEM populations. The first two highlighted the higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection (Jaljaa et al. 2022) and of adverse health outcomes, hospitalization, severe illness and mortality (Mazzalai et al. 2023) among MEM populations compared to the general population of the WHO European region. This systematic review aims to investigate whether MEM populations faced more inequalities in access to prevention, diagnosis and treatment for COVID-19 compared to the general population in the WHO European region.

Materials and methods

The project was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021247326), where the protocol was published. This systematic review was undertaken according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020).

The included studies were collected by searching the following databases: Medline, Embase, Scisearch, Biosis, and Esbiobase. The search was performed on the CAS STNext® platform that allows searching multiple databases simultaneously with a unique query and supports the removal of duplicate references during the query session.

In order to finalize the most appropriate search strategy, with the right balance between comprehensiveness and precision, the documentation center conducted a preliminary test search and evaluated the result list with the review team. Search terms included the following keywords: migrants, ethnic minorities, healthcare access, healthcare disparity, health equity, racism, social marginalization, social discrimination, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, diagnosis, treatment, and vaccine. The final search strategy used a combination of Medline and Embase thesaurus terms, exploded when necessary, and a wide range of free text words in the title and abstract field of citation records. The detailed search strategy is available as supplementary material (Appendix 1). De-duplicated results were exported to an Excel spreadsheet to simplify further data analysis and management. Extra duplicates, not automatically intercepted, were manually removed based on a review of the titles.

Furthermore, a search for preprints was carried out in PubMed, which includes preprints reporting NIH-funded COVID-19 research pulled from medRxiv, bioRxiv, ChemRxiv, arXiv, Research Square, and SSRN.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The systematic review includes studies on MEM populations’ access to healthcare for COVID-19 in the 53 countries belonging to the WHO European region, in terms of access to prevention, diagnosis, and care, published from January 1, 2020, to February 7, 2022, in English, Italian, French, and Spanish. After thorough discussion within the research group, we decided to include studies on vaccine execution, vaccine hesitancy, and access to COVID-19 information as key indicators of access to prevention. Our research strategy also encompasses access to COIVD-19 diagnosis and care.

Regarding the definition of “migrants,” “refugee,” and “ethnic minorities” (see Appendix 2), we followed the International Organization for Migration glossary (Sironi et al. 2019), the convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR 2010) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC 2021) respectively. However, there is no universally recognized definition of these terms and the differences between migrants and ethnic minorities are nuanced and dependent on the country context.

We included primary and secondary quantitative and quali-quantitative studies (cross-sectional, case–control, cohort, intervention, case-series, prevalence, or ecological studies), excluding purely qualitative studies. As far as the publication type, comments, opinions, editorials, and news were excluded; letters were included if containing original quantitative data. Reviews relevant to our topic were excluded if the primary studies had already been assessed; otherwise, primary studies, not yet evaluated, were included according to our inclusion criteria.

Fourteen researchers, properly trained and constantly monitored, were commissioned to select the studies, screening title and abstract against eligibility criteria and, later, assessing eligibility for inclusion by reading the full texts. They performed the selection two at a time, independently and resolved any disagreements through discussion with each other. If it was not possible, an assessment group intervened to solve the disagreement.

Critical appraisal, data extraction, and synthesis

The study quality, carried out in double, was assessed independently by two researchers, using the suitable Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools (Joanna Briggs Institute 2020) for each study design. Quality scores were calculated as the number of positive answers out of the number of applicable questions and converted into percentages. Studies with a score of 80–100% were considered “high quality,” 60–79% “medium quality,” and 0–59% “low quality.” Low quality studies were not excluded but contributed to the final synthesis.

The extracted data were collected in a dedicated form according to the following items: bibliographic reference, publication country, language, type of study, study period, objectives, population, comparison population if available, procedures, observation setting, outcomes, results, conclusions, limits, comments, and study quality. One researcher carried out the data extraction and the other one subsequently checked the information collected.

The two researchers discussed possible points of disagreement, both in quality assessment and data extraction, in order to reach an agreement. If it was not possible, an assessment group stepped in for a final decision.

Owing to heterogeneity of study designs and populations, meta-analysis was not performed. We reported our results in a narrative synthesis and using a harvest plot.

Results

Literature search and selection

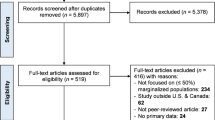

The systematic search of the literature concerning the study question, identified 2713 records on databases. After removing 1002 duplicates (870 automatically detected and 132 identified through title review), 1711 records were screened by title and abstract. Of these, 1652 were excluded for not aligning with the research topic; 59 were found eligible for full text. From the eligible studies, 19 met all the inclusion criteria and were analyzed for a quality appraisal (40 were excluded). Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of identified studies, also reporting the reason for exclusion of papers included by title/abstract screening. Overall, 13 studies were considered “high quality,” three studies “medium quality,” and three studies had a “low quality” level.

Of the 19 studies identified, 11 were about vaccine hesitancy, five about vaccine execution, two on access to COVID-19 testing, and one was about access to information on COVID-19. The majority (16) were cross-sectional studies, and three were cohort studies. No studies focused specifically on access to COVID-19 care were identified.

The definitions of migrants or ethnic minorities in the different countries were not homogeneous, thus we will quote the term used by the authors of each article. No studies specifically concerning refugees were found.

The information gathered from the included studies were reported in narrative form and divided according to the main outcomes: “vaccine hesitancy,” “vaccine execution,” “access to COVID-19 information and testing.”

In Table 1 the following data are reported: location and study period, study design, study population, sample size, main outcomes, their measures of effect (in terms of incidence, prevalence, morbidity rates, rate ratios, odds ratios, relative risks, hazard ratios), and study quality (in terms of risk of bias).

To show the distribution of the evidence, the findings of the reviews related to the outcomes “vaccine hesitancy” and “vaccine execution” are illustrated in the harvest plot shown in Fig. 2. Owing to the strong heterogeneity of the three studies on “access to COVID-19 information and testing,” these were not represented in the figure but are reported in the narrative synthesis.

Harvest plot of findings of the review related to the outcomes “vaccine hesitancy” and “vaccine execution.” Number above bar: paper reference number as reported in Table 1. Height of bar: quality of the study. Solid color: statistically significant effect. Hatched color: non statistically significant effect. * Ethno-racial status was defined by combining the criteria of place of birth, nationality, and status of the individual and both parents. **All ethnicity other than white

In the harvest plot, bars represent each measure of association between ethnicity (depicted by different colors) and outcomes (vaccine hesitancy and vaccine execution) as calculated in the included studies. For studies that reported multiple measures of association, multiple bars are shown. The number above each bar corresponds to the study's reference number as reported in Table 1. The bars are placed below either the “increased” or “decreased” boxes according to the direction of the effect. When the effect measure was found to be statistically significant, the bar is colored solid; otherwise, it has a striped pattern. The height of the bar corresponds to the quality of the study.

Vaccine hesitancy

Of the studies concerning vaccine hesitancy, eight were conducted in the UK, one in France, one in Germany, and one in Israel. Eight concerned the general population, the other three focused on healthcare workers, parents/guardians of children aged 18 months or under, and adults with disability, respectively. Overall, all studies identified reported greater vaccine hesitancy among the target population compared to the general population.

Different tools were used to assess COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and willingness, which are detailed in Table 2.

Two of the studies concerning the general population used data from a UK population-based longitudinal household survey, “Understanding Society,” based on a clustered-stratified probability sample of UK household with boost samples of key ethnic minorities. The first study (Robertson et al. 2021) showed that belonging to certain ethnic groups was associated with greater vaccine hesitancy compared to White British/Irish group. The highest odds ratios (OR) were seen in the Black or Black British group (OR 13.53, 95% CI 7.57–24.19), followed by the Pakistani or Bangladeshi group (OR 3.96, 95% CI 2.05–7.67). Adjusting for covariates (gender, age, birth country, UK country of residence, education level, shielding) made little differences to these associations (OR 13.42, 95% CI 6.86–26.24 and OR 2.54, 95% CI 1.19–5.44, respectively). The second study (Chaudhuri et al. 2022) found that the Black population was the least willing to take the COVID-19 vaccine (OR 0.004, 95%CI 0.002–0.010) followed by the South Asian group (OR 0.106, 95% IC 0.064–0.176).

Other studies from the UK confirmed these findings. A cross-sectional study conducted in Scotland among 3436 individuals (Williams et al. 2021) explored vaccine hesitancy and its association with sociodemographic factors in a survey at two time points: the first survey was conducted during national lockdown and the second 2 months later when restrictions were eased. Ethnicity had a significant effect on intention to accept a COVID-19 vaccine both in the univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses: participants of white ethnicity were almost three times as likely to accept the vaccine compared to those from Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups (adj coefficient 2.91, 95% CI 1.75–4.81) with a model adjusted for age, education level, household income, and high risk/shielding.

A further study (Allington et al. 2021) from the UK reported a positive correlation between membership of an other-than-white ethnic group and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy (rs = 0.14), conspiracy suspicions (rs = 0.11) and the use of social media for information about COVID-19 (YouTube rs = 0.19 and WhatsApp rs = 0.20). Ethnicity was uncorrelated with perceived personal risk and trust in the government. Interestingly, there was a weak negative correlation between an other-than-white ethnic group and trust in scientists (rs = −0.05) and medical professionals (rs = −0.07). The association between COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and ethnic minority membership was statistically significant when considering trust but not when considering conspiracy and vaccine attitudes in general.

A study conducted in November 2020 (Bajos et al. 2022), including 85,855 adults living in metropolitan France, focused on people who were certain not to be vaccinated. Those with a migratory background were more reluctant to get vaccinated compared to those born in France without history of migration; persons born in French Overseas Departments and their descendants were the most reluctant (OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.41–1.95), followed by second-generation migrants with parents coming from Africa/Asia (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.23–1.51), from the EU (OR 1.17 95% CI 1.06–1.28), and first-generation migrants coming from the EU (OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.03–1.31) and from Africa/Asia (OR 1.16, 95% CI 1.04–1.30).

A national cross-sectional study carried out in Israel (Green et al. 2021) conducted an internet survey using a panel of over 100,000 people, of whom 957 completed the questionnaires online. Arab participants were much more likely to say that they would completely refuse the vaccination compared to the Jewish participants (men OR 4.79, 95% CI 2.53–9.06; women OR 3.42, 95% CI 2.17–5.41). These findings were consistent after controlling for age and education differences.

Two studies conducted on the general population after the vaccination campaign had already started showed similar results. The first study (Stead et al. 2021) is a cross-sectional study conducted in early 2021, when most people aged over 80 years had been invited to have a vaccine and invitations were started also for those aged over 70. After controlling for socio demographics, those belonging to the Black/Black British group were the least likely to accept the vaccine (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 0.25, 95% CI 0.14–0.43) followed by mixed/multiple ethnic groups (AOR 0.39, 95% CI 0.21–0.71) and Asian/Asian British (AOR 0.41, 95% CI 0.28–0.61).

The second is a German study (Aktürk et al. 2021) conducted in February 2021 among patients (N = 420) of a Turkish-speaking family doctor in Munich, with sufficient knowledge of the German or Turkish language; it showed that migratory background significantly affected the vaccine intention both in the univariate analyses (OR 4.438, 95% CI 2.436–8.085) and in the multiple logistic regression model (OR 3.082, 95% CI 1.32–1.195) where authors controlled for age, sex, years of school, previous infection, and scores related to COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, and behavior.

A further study (Bell et al. 2020) used a multimethod approach combining quantitative and qualitative methods thorough a cross sectional survey and semi-structured interviews. They investigated the view on COVID-19 vaccines of 1252 parents or guardians with children of 18 months or under. It emerged that those that self-reported as Black, Asian, Chinese, Mixed, or Other ethnicity were more likely to reject a COVID-19 vaccine for themselves (OR 2.733, 95%CI 1.27–5.88) and for their children (OR 2.549, 95%CI 1.26–5.16), compared to White participants. The multivariable analysis included age, household income, location, and employment as predictive variables in both models.

Another study (Woolf et al. 2021) focused specifically on a population of multi-ethnic clinical and non-clinical UK healthcare workers (HCWs). After adjustment for socio-demographics, job, trust, perceived COVID-19 risk and psychological factors, ethnicity was significantly associated with vaccine hesitancy for Black Caribbean (AOR 3.37, 95%CI 2.11–5.37), Black African (AOR 2.05, 95%CI 1.49–2.82), Asian Chinese (AOR 1.59, 95%CI 1.15–2.20), and White Other groups (AOR 1.48, 95%CI 1.19–1.84).

Finally, a UK cross-sectional study (Emerson et al. 2021) regarding working-age adults extended the observed association between hesitancy and minority ethnic status to people with disability: when compared to White British with no disabilities, participants belonging to other ethnic groups had higher risk of being hesitant both if they had disabilities (APRR 3.79, 95%CI 2.28–6.30) or not (APRR 2.78, 95%CI 1.94–3.99).

Vaccine execution

Five studies had vaccination uptake as the main outcome. Overall, the studies pointed out that MEM populations had lower odds of being vaccinated.

Three of the studies were conducted in the UK and considered the OR of uptake of at least the first dose of SARS-CoV2 vaccine. In all these studies, MEM populations had lower vaccination rates, with the lowest rates observed among people of the Black ethnic group. The first study (Perry et al. 2021) was conducted in Wales in April 2021 among all individuals aged 50 years and over. After adjusting for age group, health and social care worker status, care home resident status and shielding status, the odds of being vaccinated were lower for individuals of Black (AOR 0.22, 95%CI 0.21–0.24), Asian (AOR 0.41, 95%CI 0.39–0.43), mixed ethnic background (AOR 0.36, 95%CI 0.34–0.38), or other (AOR 0.24, 95%CI 0.22–0.27) ethnic group compared to the aggregated White ethnic group. The second study (Nafilyan et al. 2021) involved 6,655,672 adults aged 70 years and over who were vaccinated for COVID-19 up until March 15, 2021. The vaccination rates were lower among ethnic minority groups compared to White British ethnicity, and the lowest rates were observed among people of Black African and Black Caribbean ethnic backgrounds. Compared with people of White British ethnicity, the AOR of not being vaccinated for Black African individuals was 5.01 (95% CI 4.86 to 5.16, while the OR was 7.62 (95%CI 7.40–7.84). The last study among those conducted in the UK (Martin et al. 2021) considered the health care workers (HCW) population; HCWs from ethnic minority backgrounds were significantly less likely to be vaccinated than their White colleagues, an effect most marked in those of Black ethnicity (Black OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.26–0.34; South Asian OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.62–0.72 adjusted for age, sex, deprivation, occupation, SARS-CoV-2 serology and PCR results, and the reason given for any COVID-19 related work absences).

One study from Israel (Saban et al. 2021) examined the COVID-19 vaccination rates by neighborhood socioeconomic status and ethnic group. Jewish and Arab populations were compared, defining “Jewish” or “Arab” localities if more than 90% of the population was either of Jewish or Arab ethnic composition, while cities with at least 10% Arab residents were defined as “mixed cities.” Higher rates of COVID-19 vaccination were observed in Jewish and mixed localities, and lower in the Arab population: RR for vaccination uptake between the Jewish and Arab localities was 1.07 and 1.08 for the first and second doses, respectively. The study also analyzed vaccine uptake by age group and ethnicity, since the Arab population is generally younger. Uptake was higher in the Jewish population both for under and over 60 s, for all doses, and the disparity was greater for younger than for older people: 33% difference for first dose under 60 s vs 22% for over 60 s; 37% vs 26% for second dose; 75% vs 49% for third dose.

A further study (Bentivegna et al. 2022) considered migrants living in three informal settlements in Rome: Tiburtina (Tb), Termini (Te), and Collatina (C). According to the Italian government, on September 30, 2021, the vaccination coverage of the Italian population was 79.06%, while in these settlements the average vaccination coverage was significantly lower: 13.3% in Tb, 31.4% in Te, and 35.9% in C. Considering the legal status of migrants, the irregular population had the lowest vaccination coverage (11.1% vs. 18.5% in Tb; 23.1% vs. 35% in Te; 35.7% vs. 36% in C).

Access to COVID-19 information and testing

Only 3 out of 19 studies did not concern vaccination. One study (Khan et al. 2021) investigated the readability of online COVID-19 information and its accessibility to non-native English speakers. They assessed the availability of other languages and the presence of accompanying graphic information. More than half of the websites were deemed as difficult to read, and only 3.4% and 6.8% provided information easily available in other languages and accompanying graphical information, respectively.

The other two studies focused on access to COVID-19 testing in Italy and Switzerland. The first one (Fabiani et al. 2021) compared the median date of testing positive among Italians and non-Italians nationals. Overall, non-Italian cases were diagnosed on a later date compared with Italian cases. The median date of testing positive was April 14 (IQR March 28–May 8) for non-Italian nationals compared to April 1 (IQR March 20–April 18) for Italian nationals. This difference was particularly evident among non-Italian nationals from low Human Development Index (HDI) countries (median date at diagnosis April 29; IQR April 6–June 22).

The second one (Baggio et al. 2021) compared the underserved (undocumented migrants and homeless persons) with the general population who visited the Geneva University Hospitals (HUG) outpatient COVID-19 testing centers. The main outcome was the time interval between the onset of the first symptoms evocative of COVID-19 and the date of presentation at HUG COVID-19 testing center, as a measure of the access to the screening program. Overall, there was a similar proportion of visits occurring within the first 3 days after symptoms onset in both groups (p = 0.149). There were no significant differences in the average number of COVID-19 symptoms at presentation (p = 0.408) and in the proportion of patients tested during the first month of the program (p = 0.751).

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to find whether MEM populations faced barriers accessing healthcare for COVID-19 compared to the non-migrant population in the WHO European region. Despite our research strategy covering COVID-19 prevention, diagnosis, and care, we did not find any studies specifically about access to care and treatment for COVID-19. Apart from one study (Baggio et al. 2021), for the themes we explored MEM populations resulted more disadvantaged compared to native populations.

The majority of the studies we found—16 out of 19—were about vaccination. Most of them were related to vaccine hesitancy, listed by WHO in 2019 as one of the top 10 threats to global health (WHO 2019). This is particularly true in the European region where it was identified as the main barrier to vaccination coverage (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies et al. 2018).

The COVID-19 pandemic has drawn further attention to the role of vaccine hesitancy in limiting the attainment of collective immunity (Bussink-Voorend et al. 2022; Dror et al. 2020) and, in this context, our review emphasizes that target population is particularly at risk of vaccine hesitancy compared to general population. Vaccine hesitancy is a complex problem, which is context specific, varying across time and place (MacDonald 2015). Previous evidence has shown that socio-economic factors such as level of income and level of education may affect vaccine acceptance in both directions, so that high education or high income can be both a barrier and a promoter to vaccination (Larson et al. 2014). In the studies included in our research, lower income and level of education were associated with higher COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. However, when considering ethnicity, socio-economic factors did not fully explain the higher hesitancy observed.

Some of the studies included in the review investigated reasons why minorities were more hesitant, identifying as possible motives the lower trust in government and institutions (Chaudhuri et al. 2022; Woolf et al. 2021) and conspiracy suspicious (Allington et al. 2021). This general distrust of institutions and vaccine efficacy and safety can be related to a history of unethical healthcare research and to structural racism (Njoku et al. 2021; Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies 2021). Structural racism is considered the most fundamental of the levels of racism and the one in most need of being addressed to achieve meaningful change, due to its systemic effects on health outcomes among communities (Njoku et al. 2021). It is notable that in all papers included in our review, Black ethnicity resulted the most at risk of being hesitant among MEM populations; although each local reality has its own specificity, we can hypothesize an additional factor of discrimination related to being Black, for which it would be useful to conduct other studies, addressing the issue also from a sociological point of view.

Minority ethnic communities experience different barriers to vaccine uptake; therefore, the approach to overcome them should be tailored and multimodal. Broad “catch-all” type interventions may not be as effective for some groups and may exacerbate health inequalities (Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies 2021). To be more impactful, interventions should involve multilingual, non-stigmatizing vaccine communication from trusted sources and community engagement (Martin et al. 2021; Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies 2021), especially considering that information about COVID-19 from official resources may alienate many who do not speak English as a first language, such as MEMs (Khan et al. 2021).

Our findings about vaccine hesitancy in MEM populations are in line with the results emerging from this review when concerning vaccine uptake; it is notable that, even though vaccine hesitancy is surely one of the main drivers of ethnic disparities in vaccination rates, it does not fully explain the variation in vaccine coverage for MEM populations (Kolbe 2021; Corbie-Smith 2021). Previous studies showed that administrative, legal and logistic barriers may contribute to more difficult access to vaccination for MEM populations (Njoku et al. 2021) and may be co-responsible for the lower vaccination rates observed. Examples of these barriers are the lack of accessible points of access and booking modalities through websites, which can be an obstacle for those who do not own a computer (Njoku et al. 2021). Furthermore, migrants can face barriers linked to their legal status, since, if undocumented, they can fear the risk of being detected (UN Network on Migration 2020). In a similar way, barriers such as language, cultural and social factors, can hinder the prompt access to healthcare services, likely leading to a delayed diagnosis (Fabiani et al. 2021).

The present work aligns with the findings of a systematic review previously published (Abba-Aji et al. 2022), which concluded that both migrants and ethnic minorities face numerous barriers to vaccination primarily related to language and communication issues, as well as mistrust of government and the health system. The authors concluded that there is consistent evidence showing that Black/Afro-Caribbean groups in the US and UK encounter obstacles to COVID-19 vaccine uptake linked to hesitancy. In contrast to that research, our study concentrated exclusively on the European WHO region and, as stated in the two previous systematic reviews (Jaljaa et al. 2022; Mazzalai et al. 2023), this geographical restriction was an attempt to limit the heterogeneity of the target population among different countries. Further, our objective was also to incorporate works exploring disparities in accessing COVID diagnosis and treatment processes, even though only a few studies were available on this matter. In particular, we did not find any study addressing inequalities in access to COVID-19 treatment for MEM populations, despite the presence of known barriers to healthcare access for these groups. Migrants, and undocumented migrants in particular, are often excluded from national programs for health promotion, treatment, and care (UN Network on Migration 2020).

This review has some limitations. First, although our strategy included access to treatment and care for COVID-19, we did not find any study specifically addressing this topic. In fact, the majority of the studies focused on vaccination. For this reason, we could not fully answer our research question. Second, the surveys used in some of the included papers were web-based and this may have introduced non-response and sampling biases. Additionally, our review included studies published between January 2020 and February 2022, consequently the majority of the articles that had vaccine hesitancy as the main outcome were conducted before several vaccinations had been approved and this may have influenced the results. Also, it is notable that the concept of vaccine hesitancy has been described and applied unevenly and a wide variety of methods have been used to measure it. Previous studies (Lin et al. 2020; Robinson et al. 2021) underlined that survey wording and answer options, particularly the presence or absence of unsure/undecided options, may affect vaccine acceptance and rejection estimates. This should be taken into account when reading our results since the studies included used different items to assess vaccine intention, as shown in Table 2.

Conclusion

Our research adds to other evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a greater impact on MEM populations, showing that the health system has failed to reach those most at risk. This is the third of three reviews (Jaljaa et al. 2022; Mazzalai et al. 2023) that highlighted the need for institutions to care and concern themselves for MEM populations, bringing out the urgency to advocate inclusive policies and actions. Understanding and addressing healthcare disparities is crucial for ensuring equitable and effective healthcare delivery. These findings underline the need for policymakers to prioritize strategies for building trust and engage MEM populations, and to overcome the socio-economic barriers when designing health promotion and care programs. Further studies should be conducted to investigate the inequalities in the access to diagnostic procedures and treatment for COVID-19.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Abba-Aji M, Stuckler D, Galea S, McKee M (2022) Ethnic/racial minorities’ and migrants’ access to COVID-19 vaccines: a systematic review of barriers and facilitators. J Migr Health 5:100086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmh.2022.100086

Abubakar I, Aldridge RW, Devakumar D, Orcutt M, Burns R, Barreto ML, Dhavan P, Fouad FM, Groce N, Guo Y, Hargreaves S, Knipper M, Miranda J, Madise N, Kumar B, Mosca D, McGovern T, Rubenstein L, Sammonds P, Sawyer SM, Sheikh K, Tollman S, Spiegel P, Zimmerman C, Abbas M, Acer E, Ahmad A, Abimbola S, Blanchet K, Bocquier P, Samuels F, Byrne O, Haerizadeh S, Issa R, Collinson M, Ginsburg C, Kelman I, McAlpine A, Pocock N, Olshansky B, Ramos D, White M, Zhou S (2018) The UCL–lancet commission on migration and health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet 392(10164):2606–2654

Aktürk, Zekeriya, Klaus Linde, Alexander Hapfelmeier, Raphael Kunisch, and Antonius Schneider (2021) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in people with migratory backgrounds: a cross-sectional study among Turkish- and German-speaking citizens in Munich. BMC Infect Dis 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06940-9

Allington D, McAndrew S, Moxham-Hall V, Duffy B (2021) Coronavirus conspiracy suspicions, general vaccine attitudes, trust, and coronavirus information source as predictors of vaccine hesitancy among UK residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001434

Baggio S, Jacquerioz F, Salamun J, Spechbach H, Jackson Y (2021) Equity in access to COVID-19 testing for undocumented migrants and homeless persons during the initial phase of the pandemic. J Migr Health 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMH.2021.100051

Bajos N, Spire A, Silberzan L (2022) The social specificities of hostility toward vaccination against Covid-19 in France. PLoS ONE 17(1 January). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262192

Bambra C, Riordan R, Ford J, Matthews F (2020) The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Commun Health 74(11):964–968. https://doi.org/10.1136/JECH-2020-214401

Bell S, Clarke R, Mounier-Jack S, Walker JL, Paterson P (2020) Parents’ and guardians’ views on the acceptability of a future COVID-19 vaccine: a multi-methods study in England. Vaccine 38(49):7789–7798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.10.027

Bentivegna E, Di Meo S, Carriero A, Capriotti N, Barbieri A, Martelletti P (2022) Access to COVID-19 vaccination during the pandemic in the informal settlements of Rome. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19020719

Burstrom Bo, Tao W (2020) Social determinants of health and inequalities in COVID-19. Eur J Pub Health 30(4):617–618. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURPUB/CKAA095

Bussink-Voorend D, Hautvast JLA, Vandeberg L, Visser O, Hulscher MEJL (2022) A systematic literature review to clarify the concept of vaccine hesitancy. Nat Hum Behav 6(12):1634–1648. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01431-6

Chadeau-Hyam M, Bodinier B, Elliott J, Whitaker MD, Tzoulaki I, Vermeulen R, Kelly-Irving M, Delpierre C, Elliott P (2020) Risk factors for positive and negative COVID-19 tests: a cautious and in-depth analysis of UK biobank data. Int J Epidemiol 49(5):1454–1467. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyaa134

Chaudhuri K, Chakrabarti A, Chandan JS, Bandyopadhyay S (2022) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the UK: a longitudinal household cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12472-3

Corbie-Smith G (2021) Vaccine hesitancy is a scapegoat for structural racism. JAMA Health Forum 2(3):e210434. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0434

Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, Morozov NG, Mizrachi M, Zigron A, Srouji S, Sela E (2020) Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol 35(8):775–779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y

Emerson E, Totsika V, Aitken Z, King T, Hastings RP, Hatton C, Stancliffe RJ, Llewellyn G, Kavanagh A (2021) Vaccine hesitancy among working-age adults with/without disability in the UK. Public Health 200:106–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.09.019

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2021) Reducing COVID-19 transmission and strengthening vaccine uptake among migrant populations in the EU/EEA – 3 June 2021. ECDC: Stockholm

European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Baeten R, Spasova S, Coster S et al (2018) Inequalities in access to healthcare : a study of national policies 2018. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/371408

European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Rechel, Bernd, Richardson, Erica and McKee, Martin (2018) The organization and delivery of vaccination services in the European Union: prepared for the European commission. World health organization. Regional office for Europe. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/330345

Fabiani M, Mateo-Urdiales A, Andrianou X, Bella A, Del Manso M, Bellino S, Rota MC, Boros S, Vescio MF, D’Ancona FP, Siddu A, Punzo O, Filia A, Brusaferro S, Rezza G, Dente MG, Declich S, Pezzotti P, Riccardo F (2021) Epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 cases in non-Italian nationals notified to the Italian surveillance system. Eur J Pub Health 31(1):37–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa249

Fisk RJ (2021) Barriers to vaccination for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) control: experience from the United States. Global Health J (amsterdam, Netherlands) 5(1):51–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOHJ.2021.02.005

Green MS, Abdullah R, Vered S, Nitzan D (2021) A study of ethnic, gender and educational differences in attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines in Israel – implications for vaccination implementation policies. Israel J Health Policy Res 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13584-021-00458-w

Jaljaa A, Caminada S, Tosti ME, D’Angelo F, Angelozzi A, Isonne C, Marchetti G, Mazzalai E, Giannini D, Turatto F, De Marchi C, Gatta A, Declich S, Pizzarelli S, Geraci S, Baglio G, Marceca M (2022) Risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in migrants and ethnic minorities compared with the general population in the European WHO region during the first year of the pandemic: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-021-12466-1

Joanna Briggs Institute (2020) Critical appraisal tools. Retrieved https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools

Khan S, Asif A, Jaffery AE (2021) Language in a time of COVID-19: literacy bias ethnic minorities face during COVID-19 from online information in the UK. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 8(5):1242–1248. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40615-020-00883-8

Kolbe A (2021) Disparities in COVID-19 vaccination rates across racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States. Washington, DC: office of the assistant secretary for planning and evaluation, U.S. department of health and human services

Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Eckersberger E, Smith DMD, Paterson P (2014) Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: a systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine 32(19):2150–2159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081

Lin C, Pikuei Tu, Beitsch LM (2020) Confidence and receptivity for COVID-19 vaccines: a rapid systematic review. Vaccines 9(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010016

MacDonald NE (2015) Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 33(34):4161–4164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036

Marceca M (2017) Migration and health from a public health perspective. People’s movements in the 21st Century - risks, challenges and benefits. InTech. https://doi.org/10.5772/67013

Martin CA, Marshall C, Patel P, Goss C, Jenkins DR, Ellwood C, Barton L, Price A, Brunskill NJ, Khunti K, Pareek M (2021) SARS-CoV-2 vaccine uptake in a multi-ethnic UK healthcare workforce: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med 18(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003823

Mazzalai E, Giannini D, Tosti ME, D’Angelo F, Declich S, Jaljaa A, Caminada S, Turatto F, De Marchi C, Gatta A, Angelozzi A, Marchetti G, Pizzarelli S, Marceca M (2023) Risk of Covid-19 severe outcomes and mortality in migrants and ethnic minorities compared to the general population in the European WHO region: a systematic review. J Int Migr Integr. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12134-023-01007-X

Nafilyan V, Dolby T, Razieh C, Gaughan CH, Morgan J, Ayoubkhani D, Walker S, Khunti K, Glickman M, Yates T (2021) Sociodemographic inequality in COVID-19 vaccination coverage among elderly adults in England: a national linked data study. BMJ Open 11(7):e053402. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053402

Njoku A, Joseph M, Felix R (2021) Changing the narrative: structural barriers and racial and ethnic inequities in COVID-19 vaccination. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(18):9904. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189904

Orcutt M, Patel P, Burns R, Hiam L, Aldridge R, Devakumar D, Kumar B, Spiegel P, Abubakar I (2020) Global call to action for inclusion of migrants and refugees in the COVID-19 response. Lancet 395(10235):1482–1483. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30971-5

Perry M, Akbari A, Cottrell S, Gravenor MB, Roberts R, Lyons RA, Bedston S, Torabi F, Griffiths L (2021) Inequalities in coverage of COVID-19 vaccination: a population register based cross-sectional study in Wales, UK. Vaccine 39(42):6256–6261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.019

PRISMA (2020) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Retrieved (http://www.prisma-statement.org/)

Raisi-Estabragh Z, McCracken C, Bethell MS, Cooper J, Cooper C, Caulfield MJ, Munroe PB, Harvey NC, Petersen SE (2020) Greater risk of severe COVID-19 in black, Asian and minority ethnic populations is not explained by cardiometabolic, socioeconomic or behavioural factors, or by 25(OH)-vitamin D status: study of 1326 cases from the UK Biobank. J Public Health 42(3):451–460. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa095

Rao G, Guduru AA, Papineni P, Wang L, Anderson C, McGregor A, Whittington A, John L, Harris M, Hiles S, Nicholas T, Adams K, Akbar A, Blomquist P, Decraene V, Patel B, Manuel R, Chow Y, Kuper M (2021) Cross-sectional observational study of epidemiology of COVID-19 and clinical outcomes of hospitalised patients in North West London during March and April 2020. BMJ Open 11(2):e044384. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044384

Robertson E, Reeve KS, Niedzwiedz CL, Moore J, Blake M, Green M, Katikireddi SV, Benzeval MJ (2021) Predictors of COVID-19 Vaccine hesitancy in the UK household longitudinal study. Brain Behav Immun 94:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2021.03.008

Robinson E, Jones A, Lesser I, Daly M (2021) International estimates of intended uptake and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of large nationally representative samples. Vaccine 39(15):2024–2034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.005

Saban M, Myers V, Ben-Shetrit S, Wilf-Miron R (2021) Socioeconomic gradient in COVID-19 vaccination: evidence from Israel. Int J Equity Health 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12939-021-01566-4

Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (2021) Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine uptake among minority ethnic groups executive summary

Sironi AC, Bauloz, Emmanuel M (eds) (2019) Glossary on migration. International migration law, no. 34. International Organization for Migration (IOM), Geneva

Stead M, Jessop C, Angus K, Bedford H, Ussher M, Ford A, Eadie D, MacGregor A, Hunt K, MacKintosh AM (2021) National survey of attitudes towards and intentions to vaccinate against COVID-19: implications for communications. BMJ Open 11(10). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055085

UN Network on Migration (2020) Enhancing access to services for migrants in the context of COVID-19 preparedness, prevention, and response. Retrieved from https://migrationnetwork.un.org/sites/g/files/tmzbdl416/files/docs/final_network_wg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_access_to_services_0.pdf

UNHCR (2010) Convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees. https://www.unhcr.org/media/convention-and-protocol-relating-status-refugees

WHO (2019) Ten threats to global health. Retrieved August 5, 2023, https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

WHO (2023) WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. Retrieved July 27, 2023, https://covid19.who.int/

Williams L, Flowers P, McLeod J, Young D, Rollins L (2021) Social patterning and stability of intention to accept a COVID-19 vaccine in Scotland: will those most at risk accept a vaccine? Vaccines 9(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010017

Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, Curtis HJ, Mehrkar A, Evans D, Inglesby P, Cockburn J, McDonald HI, MacKenna B, Tomlinson L, Douglas IJ, Rentsch CT, Mathur R, Wong AYS, Grieve R, Harrison D, Forbes H, Schultze A, Croker R, Parry J, Hester F, Harper S, Perera R, Evans SJW, Smeeth L, Goldacre B (2020) Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 584(7821):430–436. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4

Woolf K, McManus IC, Martin CA, Nellums LB, Guyatt AL, Melbourne C, Bryant L, Gogoi M, Wobi F, Al-Oraibi A, Hassan O, Gupta A, John C, Tobin MD, Carr S, Simpson S, Gregary B, Aujayeb A, Zingwe S, Reza R, Gray LJ, Khunti K, Pareek M (2021) Ethnic differences in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy in United Kingdom healthcare workers: results from the UK-reach prospective nationwide cohort study. Lancet Region Health - Europe 9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100180

World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe (2018) Report on the health of refugees and migrants in the WHO European region: no public health without refugee and migrant health. World health organization. Regional office for Europe. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/311347

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within Italy Transformative Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conceptualization and design. Maria Elena Tosti, Franca D’Angelo, and Scilla Pizzarelli performed the literature search. Maria Elena Tosti led the methodology and coordinated the data analysis. Chiara De Marchi, Arianna Bellini, Angela Gatta, Caterina Ferrari, Salvatore Scarso, Giulia Marchetti, Francesco Mondera, Giancosimo Mancini, Igor Aloise, Marise Sabato, Leonardo Maria Siena, Dara Giannini, and Anissa Jaljaa screened the records and performed the data analysis. Chiara De Marchi and Arianna Bellini drafted the manuscript. Maria Elena Tosti, Franca D’Angelo, Silvia Declich, and Maurizio Marceca contributed to interpretation of the results. All authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This is an observational study; therefore, no ethical approval is required.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chiara De Marchi and Arianna Bellini contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

De Marchi, C., Bellini, A., Tosti, M.E. et al. Access to COVID-19 information, diagnosis, and vaccination for migrants and ethnic minorities in the WHO European region: a systematic review. J Public Health (Berl.) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-024-02325-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-024-02325-9