Abstract

Aim

To assess men’s experiences when diagnosed with breast cancer.

Subject and Methods: The breast is a symbol of femininity. Therefore, it is no surprise that studies on women’s experiences with breast cancer predominate in the literature. Because breast cancer accounts for just 1% of all cancers among men, it is often overlooked. Nevertheless, it accounts for proportionately more deaths than penile or testicular cancer. Five major databases were queried in December 2022 to review primary studies with qualitative design.

Results

Of the 206 articles selected and screened, eight met the inclusion criteria. Three highlighting men’s experience with stigmatisation and their need to be taken into consideration, even through information not solely aimed at women, are from a German study conducted between 2018 and 2020. Three from the UK between 2003 and 2007, also emphasise the stigma and the need for more information directed specifically at men. The study from the United States points out that men who receive treatment in women’s care spaces experience feelings of inadequacy. Last, a recent Israeli paper (2021) describes how men conceal the disease to avoid the stigma altogether.

Conclusion

The paper examines the paltry, recent research on men’s emotional experience with breast cancer, which is culturally relegated to women. However, a clear need emerges for more attention to be paid to addressing communications and relations for these male patients as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Breast cancer (BC) is considered a uniquely female disease due to its prevalence in women (Midding et al. 2018). The rise of breast cancer awareness and prevention campaigns among women has reinforced its perception as an issue of exclusive interest to the female gender. Breast cancer is often represented culturally as synonymous with vulnerability and distress, whilst society expects men to be strong and stoic in the face of adversity (Puntoni et al. 2011). Breast cancer is therefore incongruent with the dominant conception of the male (Robertson 2007). Current approaches to breast cancer and the related “pink ribbon culture” have further perpetuated gendered notions about the disease (Sulik et al. 2012). The pink ribbon has become the symbol of breast cancer, resulting in measures being implemented to improve research, patient support and services for women (Kaiser 2008; King 2006). Thus, the “pink ribbon culture” involves a broad community that support women (Gibson et al. 2014), making it the dominant representation, despite its being clearly non-inclusive. Men, too, can develop this disease. The overall prevalence for male breast cancer (MBC) worldwide ranges from 0.5 to 1.8% (Ruddy and Winer 2013). This low incidence often deters men from seeking timely medical care and professional and social support whilst also increasing body image issues (Iredale et al. 2006). The increasing numbers of MBC cases have led to considerable efforts in its study: namely biological and epidemiological features, gender differences, clinical manifestations, treatment modalities, diagnostic factors, prognoses and outcomes (Giordano 2018). These studies have shown that the epidemiological characteristics and stages of BC are similar between men and women. From an oncological perspective, breast cancer occurs in men and women for similar biological reasons. Nevertheless, socially, breast cancer among men has been kept separate from the disease among women.

There are, however, fundamental differences in the course of the disease in the two genders. Men are frequently diagnosed later in life because most breast symptoms tend to be misdiagnosed as gynaecomastia, which leads to the progression of tumours that manifest with larger sizes and increased spread of lymph node metastases (Greif et al. 2012). Men, therefore, are more likely to reach an advanced stage prior to diagnosis, which makes them susceptible to poor prognoses and reduced chances of survival (Greif et al. 2012; Lautrup et al. 2018), with an overall survival rate of 82.8% for men with BC, compared to 88.5% for women (Liu et al. 2018).

The most important differences between BC in men and women involve the personal reaction and social impact of the disease, as well as the effect of treatment modalities on self-care and nursing needs (Giordano 2018). The care needs, experiences, quality of life and psychological health of women with BC have been well documented (Cebeci et al. 2012), whilst discussions of the disease and lived experiences in men are nearly non-existent. Acquiring this understanding is essential for the development of an effective care plan for men receiving treatment in different cancer settings such as inpatient, surgery and palliative care. Research on MBC has been conducted primarily in medicine (Giordano 2018) and nursing (Nemchek 2018). Giordano (2018) provided a review to determine the epidemiological, pathological and clinical features, prognoses and treatment modalities of MBC. In addition, Nemchek (2018) examined the reasons for gender inequality and measures implemented to address the problems resulting from this inequality. The results of these reviews, although very useful, provided limited insight into the overall experiences of men with BC and no specific implications for nursing care. Although cases of MBC are rare, nurses should be able to discern the best possible management of such patients to improve their quality of care (Al-Haddad 2010). Limited knowledge of MBC cases, the needs of these men with BC, and the impact that MBC has on men and their quality of life, places them at a distinct disadvantage (Lewis-Smith 2016), which could adversely affect the nursing care they receive. Therefore, it is essential to understand the experiences and needs of men with BC to ascertain how nurses can provide better holistic care to men who have been diagnosed with BC.

The ultimate purpose of this paper is to investigate whether there are any qualitative studies in the literature that have explored the lived experience of men diagnosed with breast cancer.

Research question

Are there any studies describing the experience of men diagnosed with malignant breast cancer?

Methods

A qualitative systematic literature review was conducted between November 2022 and February 2023. The aim of this research was to investigate the lived experience of men diagnosed with breast cancer.

Research strategy

In line with the PRISMA Statement (Moher et al. 2009), the Web of Science, PubMed, Cinhal, Embase and Wiley databases were explored. A combination of keywords was applied to the queries for each database, which in the case of PubMed was: ((“Breast Neoplasms, Male”[Mesh]) OR “Breast Neoplasms, Male”[Majr]) OR ((“Breast Neoplasms”[Mesh]) OR “Breast Neoplasms”[Majr]) AND “men”). Depending on the search possibilities of each database, the presence of these keywords was sought preferentially in the title and abstract, otherwise in the full text.

Inclusion criteria for studies

The following inclusion criteria were adopted to identify the articles: primary literature studies with a qualitative and/or mixed design, aiming to explore the experience of men who had been diagnosed with malignant breast cancer (regardless of histological and morphological type, and TNM staging), written in English or Italian without any time limit. Secondary studies, dissertations, theses, lectures and recommendations, whilst books were excluded.

Data extraction (selection and coding)

The screening of the titles and abstracts was conducted independently by the two authors, after which they, again independently, checked and read the full texts, verifying that they met the inclusion criteria. No disagreement occurred between the two authors, thus avoiding the need for a third party. The full text of all the studies of interest was obtained directly from the libraries surveyed. Hence, it was not necessary to contact the authors of the papers. Extracted data were classified according to the following categories: year of publication, author(s), article title, country of study, purpose and conclusions (Table 1).

Results

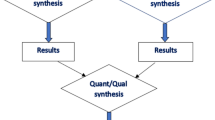

Of the 2823 references from the queried databases, removal of duplicates resulted in 206 articles being screened, which, following exclusion by title and abstract led to the reading of 23 full texts, resulting in the final inclusion of eight papers that met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

The papers included were published over a rather brief span of time between 2003 and 2021. Three of them (Halbach et al. 2020; Hiltrop et al.2021; Midding et al. 2018) are part of the German N-MALE project study (Male breast cancer: patient’s needs in prevention, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation and follow-up-care), which was started in April 2016 and which ended in March 2018. The intention of the programme was to identify the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation and follow-up needs of men with breast cancer. In “Men with a ‘Woman’s Disease’: Stigmatization of Male Breast Cancer Patients—A Mixed Method Analysis” (Midding et al. 2018) the feminisation of breast cancer was described. The authors used a mixed method to collect qualitative interviews (n = 27) and quantitative data (n = 100). These data tended to highlight the theme of stigmatisation and ignorance regarding male breast cancer mainly in cancer care settings and in the workplace, where men reported that they had the feeling of being isolated from colleagues and projects. In the healthcare system, male breast cancer patients (MBCPs) reported that they felt unwelcome and awkward while intruding in an area normally reserved for women.

The second article derived from the N-MALE project (Halbach et al. 2020) focused on exploring the health situation of MBCPs from their own perspective. The sample and method used were the same as those described in Midding et al. (2018). Positive experiences emerged, alongside findings of shortcomings such as delays in diagnosis, uncertainty of health professionals about treatment, experiences of stigmatisation and problems with continuity of care, including unclear responsibilities for aftercare and difficulties in accessing specific breast cancer care for men in a gynaecological context.

Also within the same N-MALE project, Hiltrop’s (Hiltrop et al. 2021) paper involved the sample of 27 participants described in Midding et al. (2018) with the aim of exploring the MBCPs’ experiences of returning to work and in particular of answering questions regarding the type of return-to-work patterns among them. This included the MBCPs’ reported motivations to return to work, how they experienced their return to work and how their illness affected their work after they had returned. Among the motivations that emerged for returning to work were the desires for normality and for diversion, the need to stay active and to maintain social contacts. They also viewed work as a source of pleasure, along with its economic motivations, whilst the lack of perception of being ill and the possibility of having a job that requires little physical effort were also deemed significant. Participants reported a positive workplace experience throughout the period of illness right up through their return to their jobs, although they did emphasise that there was a perceived experience of stigmatisation. The consequences of the illness and treatment led to changes in the respondents’ productivity, e.g. due to fatigue.

The aim of Nguyen’s German paper (Nguyen et al. 2020) was to explore the experiences of men with breast cancer by identifying their needs for care and support. The interviews, which involved a group of 18 MBC patients, revealed a largely neutral experience of being affected by this “women’s disease”, although some felt that stigmatisation did threaten their masculinity. They reported the perception that being male appeared to be an obstacle to accessing adequate care. In fact they identified key barriers to their care options, including lack of awareness and experience in treating men for BC among health professionals, as well as the perception that all breast cancer research was based on female populations and that there was a lack of dedicated support services for MBCPs.

Williams’ paper (Williams et al. 2003) was aimed at exploring the experiences of men in England who had been diagnosed with breast cancer and comparing them with those of women with the same disease and the experiences of health professionals caring for both groups of patients. A series of four focus groups was conducted, and the groups included men with cancer, women with breast cancer and a group of healthcare professionals (breast surgeons, nurses and oncologists) with a total of 27 people. The men reported that they went to their doctor because of their partner’s insistence. Most men indicated that they would appreciate the opportunity to talk to another man with breast cancer. Iredale’s paper (Iredale et al. 2007) was also conducted in England through multi-stage research. Most of the men surveyed were shocked to receive the diagnosis of breast cancer, whilst sharing that diagnosis resulted in embarrassment and stigma. In this paper, too, there emerged the issue that only limited information on MBC was available. What was available was often viewed as inappropriate as it was originally intended for women. The study conducted in the USA (Walker and Berry 2020), part of a longer paper, analysed the experiences of five men. Once again, their reporting revealed the total inadequacy of their having to be cared for in treatment spaces dedicated to women.

Most recently, the Israeli paper (Levin-Dagan and Baum 2021) involved 16 men. Interestingly, the results showed that the participants faced stigmatising situations both inside and outside healthcare facilities. These men’s coping styles showed situational responses wherein they used disengagement, such as concealment and selective disclosure, with the aim of destigmatising their being affected by MBC.

Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of this review was to investigate qualitative studies in the literature that have explored the lived experience of men diagnosed with breast cancer. The inquiry highlighted the paucity of primary research relating to the experience of men with breast cancer and the newness of the albeit limited debate. The themes that emerged further highlighted the difficulties and challenges of men with BC as well as the negative effects that the disease had on their personal and social lives. What was most significant was that men reported that they also felt stigmatised and rejected within healthcare facilities due to a lack of knowledge on the part of the population in general and the healthcare professionals in particular. MBCPs reported that they experienced delays in diagnosis, which led to poorer physical, psychological and emotional consequences than what women with the same diagnosis reported. In this regard, it is important to emphasise the important role played by a (female) partner both in early diagnosis (Seymour-Smith et al. 2002) and during the male breast cancer experience. This involvement of MBCP’s female partners is a point that should be encouraged and supported.

The investigation also found that men reported that they felt stigmatised to varying degrees and, despite some positive experiences, they generally experienced a number of negative occurrences that could be considered direct consequences of social and health self-stigmatisation. Though some studies (Midding et al. 2018; Halbach et al. 2020; Levin-Dagan and Baum 2021) have provided an account of the reported stigmatisation of men with BC, through accounts of feelings of exclusion (Midding et al. 2018) at the level of healthcare of German MBCPs, further research is clearly needed in other Eastern and Western contexts. The finding that men have suffered greater stigmatisation in the oncological care system, that healthcare providers tend to lack gender-specific information on BC and that providers fail to meet the care needs of men is, without doubt, cause for concern. Men reported that they felt that they were being marginalised in clinical settings, that they were being excluded from clinical facilities and that women received preferential treatment in the wards. Nurses need to be more aware of MBCPs’ needs. Indeed, it is important to note that despite a low prevalence of MBC, health workers should be well informed about MBC and that measures should be taken to ensure that men will also be provided with holistic care. Nurses in outpatient clinics need to make sure that male patients are not marginalised and that their concerns are properly addressed and managed, whilst at the same time they should ensure that MBCPs feel respected by hospital staff. Hospitals, in turn, should support nursing work by developing brochures that outline information that is not only addressing women but that also includes indications for MBCPs. Including photographs of male mastectomies in illustrative materials would be an easy and inexpensive way to improve care for men affected by BC.

Social stigmatisation resulting in hidden fears has also been found to prevent men from revealing their illness beyond their immediate family. This frequently results in men using coping strategies that are more often negative (avoidance and denial) than positive (Levin-Dagan and Baum 2021). Therefore, there is clearly a need for social and cultural awareness of these challenges for men as well as for social and healthcare measures that will promote men’s well-being. Gender-related stigmatisation has undoubtedly influenced men’s experiences of BC and has required them to manifest their gendered character in different ways. If the pink ribbon culture refers to BC awareness and the colour pink symbolises women, it is necessary to raise awareness about MBC by using blue ribbons as well (Quincey et al. 2016).

Even following rehabilitation, men have often reported that they were affected by a disturbed body image and significant limitations in their daily life and in the workplace. Future research is evidently called for since an altered body image among MBCPs, as has been shown for WBCPs, can cause additional social, emotional and family stressors over the long term, which, if addressed appropriately, could be mitigated.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Al-Haddad M (2010) Breast cancer in men: the importance of teaching and raising awareness. Clin J Oncol Nurs 14(1):31–32

Cebeci F, Yangın HB, Tekeli A (2012) Life experiences of women with breast cancer in south western Turkey: a qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 16(4):406–412

Gibson AF, Lee C, Crabb S (2014) ‘If you grow them, know them’: discursive constructions of the pink ribbon culture of breast cancer in the Australian context. Fem Psychol 24(4):521–541

Giordano SH (2018) Breast cancer in men. N Engl J Med 379(14):1385–1386

Greif JM, Pezzi CM, Klimberg VS, Bailey L, Zuraek M (2012) Gender differences in breast cancer: analysis of 13,000 breast cancers in men from the National Cancer Data Base. Ann Surg Oncol 19(10):3199–3204

Halbach SM, Midding E, Ernstmann N, Würstlein R, Weber R, Christmann S, Kowalski C (2020) Male breast cancer patients’ perspectives on their health care situation: a mixed-methods study. Breast Care 15(1):22–29

Hiltrop K, Heidkamp P, Halbach S, Brock-Midding E, Kowalski C, Holmberg C et al (2021) Occupational rehabilitation of male breast cancer patients: return patterns, motives, experiences, and implications-a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care 30(4):e13402

Iredale R, Brain K, Williams B, France E, Gray J (2006) The experiences of men with breast cancer in the United Kingdom. Eur J Cancer 42(3):334–341

Iredale R, Williams B, Brain K, France E, Gray J (2007) The information needs of men with breast cancer. Br J Nurs 16(9):540–544

Kaiser K (2008) The meaning of the survivor identity for women with breast cancer. Soc Sci Med 67(1):79–87

King S (2006) Pink Ribbons Inc.: the emergence of cause-related marketing and the corporatization of the breast cancer movement. Governing the female body: gender, health, and networks of power. State University of New York Press, pp 85–111

Lautrup MD, Thorup SS, Jensen V, Bokmand S, Haugaard K, Hoejris et al (2018) Male breast cancer: a nation-wide population-based comparison with female breast cancer. Acta Oncol 57(5):613–621

Levin-Dagan N, Baum N (2021) Passing as normal: negotiating boundaries and coping with male breast cancer. Soc Sci Med 284:114239

Lewis-Smith H (2016) Breast cancer or chest cancer? The impact of living with a ‘woman’s disease.’ J Aesthet Nurs 5(5):240–241

Liu N, Johnson KJ, Ma CX (2018) Male breast cancer: an updated surveillance, epidemiology, and end results data analysis. Clin Breast Cancer 18(5):e997–e1002

Midding E, Halbach SM, Kowalski C, Weber R, Würstlein R, Ernstmann N (2018) Men with a “woman’s disease”: stigmatization of male breast cancer patients-a mixed methods analysis. Am J Mens Health 12(6):2194–2207

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535

Nemchek L (2018) Male breast cancer: examining gender disparity in diagnosis and treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs 22(5):E127–E133

Nguyen TS, Bauer M, Maass N, Kaduszkiewicz H (2020) Living with male breast cancer: a qualitative study of men’s experiences and care needs. Breast Care 15(1):6–12

Puntoni S, Sweldens S, Tavassoli NT (2011) Gender identity salience and perceived vulnerability to breast cancer. J Mark Res 48(3):413–424

Quincey K, Williamson I, Winstanley S (2016) ‘Marginalised malignancies’: a qualitative synthesis of men’s accounts of living with breast cancer. Soc Sci Med 149:17–25

Robertson S (2007) EBOOK: understanding men and health: masculinities, identity and well-being. McGraw-Hill, Maidenhead

Ruddy KJ, Winer EP (2013) Male breast cancer: risk factors, biology, diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship. Ann Oncol 24(6):1434–1443

Seymour-Smith S, Wetherell M, Phoenix A (2002) ‘My Wife Ordered Me to Come’!: a discursive analysis of doctors’ and nurses’ accounts of men’s use of general practitioners. J Health Psychol 7:253–267

Sulik GA, Cameron C, Chamberlain RM (2012) The future of the cancer prevention workforce: why health literacy, advocacy, and stakeholder collaborations matter. J Cancer Educ 27(2 Suppl):S165-172

Walker RK, Berry DL (2020) Men with breast cancer experience stigma in the waiting room. Breast J 26(2):337–338

Williams BG, Iredale R, Brain K, France E, Barrett-Lee P, Gray J (2003) Experiences of men with breast cancer: an exploratory focus group study. Br J Cancer 89(10):1834–1836

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Brescia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. No funding was received for conducing this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors collaborated in writing the article to the same extent.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study is a review of published literature and therefore is exempt from requiring ethical approval.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guarinoni, M.G., Motta, P.C. The experience of men with breast cancer: a metasynthesis. J Public Health (Berl.) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-024-02307-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-024-02307-x