Abstract

Aim

This article simultaneously examines the influence of Schwartz’ higher-order human values (self-transcendence, openness to change, self-enhancement, and conservation) and conspiracy beliefs on four COVID-19-related dependent variables.

Subject and methods

Using path analysis with large-scale panel data from Germany (N = 4382), we tested if the correlational effects of higher-order values as independent variables on the perceived threat of the infection event, evaluation of government measures, number of self-initiated measures, and trust toward individuals and institutions involved as dependent variables could be mediated by conspiracy beliefs.

Results

We found evidence of a significant influence of all four higher-order values on the strength of conspiracy beliefs. In addition, we detected effects of higher-order values and conspiracy beliefs on all four COVID-19-related measures. Self-transcendence with consistently positive and openness to change with consistently negative total, direct, and indirect effects provided the most evident results. The respondents’ country of origin and residence in East or West Germany affected all four COVID-19-related variables.

Conclusion

This article has shown that belief in conspiracy narratives reveals associations of higher-order values with all four COVID-19-related measures that would not have been apparent without this mediator. In doing so, it contributes to the understanding of how pandemic mitigation measures are implemented differently. The results of this study can improve the ability to develop and enforce policies to increase the acceptance of scientifically accepted efforts in better governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the spring of 2020, the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) spread worldwide. In the early days of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) crisis, before there was supply of vaccines, the world’s nations heavily relied on citizen participation. Much depended on how consistently citizens followed government measures, such as contact restrictions, wearing masks, or disinfecting their hands. Trust in government institutions and the public health system was, and still is, an important factor in COVID-19 conditional decisions such as vaccination (Viskupič et al. 2022). However, the behavior of citizens—especially in times of crisis, when the threat is significant, but information is scarce—could be influenced, among other things, by their value system, based on which they perceive and evaluate the situation (Schwartz and Bilsky 1987). It is possible that, e.g., people who have learned that the good of the general public and environment is higher than their own may be more willing to comply with unpleasant constraints (Motta and Goren 2021). Nevertheless, in the case of complex events on a global scale with a confusing information situation, not all information can be evaluated in the same manner: conspiracy narratives arose as soon as the first news of an unknown virus became known (Douglas 2021; Gómez-Ochoa and Franco 2020).

With this manuscript, we pursue two aims. First, we want to assess the influence of Schwartz’ higher-order human values (self-transcendence, openness to change, self-enhancement, and conservation) and conspiracy beliefs on four COVID-19-related dependent variables: perceived threat of the infection event, evaluation of government measures, number of self-initiated measures, and trust toward individuals and institutions involved. Second, we examine whether conspiracy beliefs mediate between values and the four COVID-19-related measures. Therefore, in general, this study links the findings of previous studies on COVID-19 and conspiracy beliefs, as the extensive evaluation of the contribution of human values to conspiracy beliefs is still under-represented in the extant literature. In particular, this study narrows the gap in research regarding how basic human values affect vital decision-making of national significance through the formation and evaluation of conspiracy beliefs.

In the following section, we derive the hypotheses for the study by examining the current state of research and identifying the necessary theoretical underpinnings. The next part describes the sample used, the construction of variables and the analysis design. In the subsequent section the results will be presented. Afterward, the results will be discussed and placed in the context of the current state of research.

Theoretical background

Since the pandemic outbreak, many studies have emerged about COVID-19, including many that provide results on the drivers and consequences of the infectious event (for a systematic review, see van Mulukom et al. 1982. While researchers have often focused on the association between the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the personalities of individuals (e.g., Bojanowska et al. 2021; Bonetto et al. 2021) and how they deal with it (Enea et al. 2023; Huang et al. 2022), there are now also numerous studies related to conspiracy beliefs and the coronavirus (Georgiou et al. 2020; Hughes and Machan 2021; Kuhn et al. 2021). Values are formed through socialization and education in a social and personal context and are considered relatively stable at the onset of adulthood (Bilsky et al. 2011). They are the underlying dispositions for beliefs, attention and behavior (Rokeach 1969) since they are considered guiding principles in life that refer to desirable goals (Parks and Guay 2009; Schwartz 2012a). In this regard, values according to the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy are considered determinants of attitudes and thus of behavior (Homer and Kahle 1988). We therefore assume that values also affect the evaluation and implementation of containment measures, the assessment of institutions and individuals involved, and the perception of risk. For the same reasons, values should also affect the formation of conspiracy beliefs. On the one hand, values are considered underlying dispositions for beliefs (Rokeach 1969); on the other hand, there is evidence from research on conspiracy beliefs that points to basic human values as motivational drivers: Douglas et al. (2017) identify existential, social, and epistemic motives as drivers of conspiracy beliefs. Epistemic motives include the desire to understand and be able to explain the world (Douglas et al. 2017) and drive individuals to recognize patterns even in random events (Gligorić et al. 2021; Zhao et al. 2014). This motivation overlaps with the higher-order value of openness to change, especially with the value self-direction (Schwartz 2012a). Existential motives are reflected in the desire for security and control and express that people aim to feel safe in their environment (Douglas et al. 2017; Gligorić et al. 2021). This motivation is embodied in the values of conformity, tradition, and security, which constitute the higher-order value of conservation (Schwartz 2012a). Finally, social motives can also contribute to the endorsement of conspiracy beliefs. A positive self-image of the individual or in-group can be achieved by giving credence to conspiracy beliefs (Cichocka et al. 2016). This is expressed through the need for uniqueness, i.e., the desire to be different, independent, and non-conformist (Lantian et al. 2017; Imhoff and Lamberty 2017). Social motives are placed on the side of values with a personal focus in Schwartz’s value continuum and are reflected by both self-enhancement values (self-direction) and openness to change values (power, achievement) (Schwartz 2012a). Accordingly, there is not only a theoretically based causal relationship between human values and COVID-19-related attitudes and behavior but also between values and conspiracy beliefs. The influence of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs on the assessment and implementation of containment measures, the assessment of perceived threats, and trust in the institutions and people involved have been extensively researched (for an overview, see, e.g., van Mulukom et al. (1982)). The studies found, e.g., negative associations between conspiracy beliefs and attitudes toward vaccines (Pivetti et al. 2021), between conspiracy beliefs and adherence to government guidelines (Freeman et al. 2022) or social distancing behavior (Marinthe et al. 2020), while there were, e.g., positive relations to “non-normative actions and behaviors which go against governmental regulations” (Marinthe et al. 2020).

The above-mentioned theoretical foundations of the relations suggest that values not only have an influence on conspiracy beliefs and COVID-19-related attitudes and behavior but that conspiracy beliefs affect COVID-19-related measures and that there is a mediating role of conspiracy beliefs between values and the COVID-19-related evaluation and implementation of containment measures, the assessment of institutions and individuals involved, and the perception of risk. Either way, the relationship of human values, corona conspiracy beliefs, and pandemic-related attitudes and behaviors, such as perceived threat of infection, belief in the effectiveness of the measures, trust in institutions, and avoidance behavior, remains little explored (van Mulukom et al. 1982). In the following, we explain the constructs used and present the relevant literature.

Basic human values and higher-order values

In current psychological research, the term values can be defined as “… conceptions of the desirable that guide the way social actors (e.g., organizational leaders, policy-makers, individual persons) select actions, evaluate people and events, and explain their actions and evaluations” (Schwartz 1999). Schwartz’s theory of basic human values (Schwartz and Bilsky 1987, 1990) belongs to the most popular and most researched models to date (Knafo et al. 2011; Sagiv and Roccas 2021). Values can be captured at the level of the individual but are also communicated and shared within a common cultural or social group. In this context, the individual’s own experiences, education, and socialization contribute to the long-term development of value expressions (Bilsky et al. 2011). The revised version of the value continuum (Fig. 1) comprised 19 values, aggregated into four higher-order values: self-transcendence, openness to change, self-enhancement, and conservation (Schwartz et al. 2012b; Schwartz 2017; Cieciuch et al. 2014).

Modified version of the motivational continuum of values. Note: In the innermost circle, the circumplex structure of the 19 revised human values is shown. Surrounding this, the four higher-order values along the two dimensions of openness vs. conservation and self-transcendence vs. self-enhancement are shown. Moving outward, the next circle divides the values into social and personal focus. The outermost circle distinguishes between the dimensions anxiety–avoidance and anxiety–freedom. Source: Poier et al. (2022), based on Schwartz et al. (2012b)

People with a high degree of self-transcendence are interested in the well-being of others and care about community and nature. Individuals who exhibit a high degree of openness to change appreciate having new experiences. They prefer independent thinking and self-realization to a conformist life. Individuals scoring high on self-enhancement strive for personal success. Prestige and social status are important to them, just as is the need to dominate others. People with high conservation values have a need for security. They prefer adherence to traditional customs and reject inappropriate behavior. The four higher-order values form the extreme manifestations of a two-dimensional field of self-enhancement vs. self-transcendence values (personal- vs. other-related focus) on the one dimension and openness vs. conservation values (preservation vs. change of the status quo) on the other. (Schwartz 2012a; Witte et al. 2020).

Regarding the literature on values related to COVID-19, Wolf et al. (2020) suspected that human values “play a widespread role in shaping responses to the COVID-19 pandemic” and suggested from the existing theory self-transcendence to be positively influencing compliance with the COVID behavioral prescriptions. Either way, little is known to date about the role of Schwartz’ human values as predictors of COVID-19 related behaviors. Bonetto et al. (2021) examined the role of values as dependent variables during the pandemic in France. Although values are considered to be relatively stable, they found significant but weak changes in conservation, self-enhancement, and openness to change. In addition to these small changes, which the authors attributed to the influence of the perceived threat of the pandemic, they reported consistent positive effects of self-transcendence and conservation on compliance with movement restrictions and social distancing and a small negative effect of self-enhancement on social distancing during the pandemic. This statement was confirmed in a study from Italy. Here, Pivetti et al. (2023) could prove an indirect effect of universalim values and a direct effect of benevolence values, both values included in self-transcendence, on the probability of vaccination against COVID-19. These results could be supported by Moosa et al. (2022) from the Maldives and Torres et al. (2023) in Brazil who found that conservation and self-transcendence positively determined vaccine behavior. Motta and Goren (2021) investigated the relationship between basic human values and prosocial health behavior such as wearing masks in public, social distancing, and avoidance of the formation of larger groups in the US. They reported that self-transcendent people were more likely to engage in prosocial health behaviors. Therefore, we expect similar results for the present study and hypothesize the following:

-

H_01: Self-transcendence has a positive relationship with the evaluation of government measures and the number of measures taken.

Although Wolf et al. (2020) also estimated the influence of conservation on containment measures to be positive, there is evidence for a strong relation between politically conservative orientation and conservation values (Ponizovskiy et al. 2020; Schwartz et al. 2010; Caprara et al. 2008). However, since conservative individuals are found to be more susceptible to conspiracy beliefs and therefore would be less likely to follow recommendations (Latkin et al. 2021; Calvillo et al. 2020), these contradictory indications make conservation values appear ambiguous.

Conspiracy beliefs

During the past few decades, studies concerning conspiracy beliefs focused mainly on attitudes to politics or authorities (Swami and Furnham 2012; Imhoff and Bruder 2014), self-esteem (Cichocka et al. 2016), social dominance orientation (Swami 2012), or the need for uniqueness (Lantian et al. 2017). However, although there are some studies on personality traits in relation to conspiracy beliefs (Goreis and Voracek 2019; Swami et al. 2016), the research base is limited regarding interaction with basic human values and higher-order values.

Douglas et al. (2019) identify a conspiracy as a “secret plot by two or more powerful actors,” stressing that, “while a conspiracy refers to a true causal chain of events, a conspiracy theory refers to an allegation of conspiracy that may or may not be true.” Swami et al. (2014b) add to this definition, “… a subset of false beliefs in which the ultimate cause of an event is believed to be due to a plot by multiple actors working together with a clear goal in mind, often unlawfully and in secret” (Swami et al. 2014a). Consequently, conspiracy beliefs offer alternative explanations for established knowledge and thus lead to less than optimal or less expected outcomes according to the currently prevailing scientific view—including a negative impact on health decisions (Jolley and Douglas 2014; Oliver and Wood 2014b). This can include unreasonable epidemic behavior. As explained at the beginning of “Theoretical background” section, studies on the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and COVID-19-related measures found, e.g., negative associations between conspiracy beliefs and attitudes toward vaccines (Pivetti et al. 2021), between conspiracy beliefs and adherence to government guidelines (Freeman et al. 2022) or social distancing behavior (Marinthe et al. 2020), while there were, e.g., positive relations to non-normative behavior which counteract governmental regulations (Marinthe et al. 2020; Jolley et al. 2019). Pavela Banai et al. (2022) and Karić and Međedović (2021) could detect direct negative effects of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs on adherence to preventive measures and a direct negative effect on trust in government officials. Latkin et al. (2021) found that COVID-19 skepticism not only stems from conservative political attitudes but also leads to downplaying the dangers of COVID-19. Taken together, we make the hypothesis:

-

H_02: Conspiracy belief has a negative association with the four COVID-19-related outcomes (perceived threat of infection with the coronavirus, behavioral changes measured by the number of measures taken, beliefs in the effectiveness of public policy measures to mitigate the spread of the pandemic, and trust in politics and institutions).

Existential, social, and epistemic motives are considered drivers of conspiracy beliefs (Douglas et al. 2017). They relate to the need for security and control, the desire to maintain a positive image of oneself and one’s social group, and an understanding of one’s environment, respectively. Epistemic motives are based on a desire to understand the big picture in the world, trying to construct explanations where information is scarce and to find patterns where events are merely random (Douglas et al. 2017). Conspiracy beliefs serve here to make sense and thus take on a role similar to religion and spirituality (van Prooijen 2020). In a similar manner, Saroglou (2014) postulated a positive correlation between conservation values and religiosity.

According to the assumption that existential motives foster conspiracy beliefs, people turn to conspiracy beliefs when they feel anxious (Grzesiak-Feldman 2013), powerless (Abalakina-Paap et al. 1999), or feel a lack of sociopolitical control (Bruder et al. 2013). Accordingly, values from the self-protection hemisphere (conservation, self-enhancement) should support the belief in conspiracy narratives. In contrast, values from the growth hemisphere (openness to change, self-transcendence) should counteract it. The need for security and control is reflected here in the corresponding values “security” and “control,” which are assigned to the higher-order value of conservation (Schwartz 2012a). Farrell et al. (2019) found that individuals with high levels of security, conformity, and tradition had greater difficulty assigning the correct truth value to a story and recognizing the difference between subjective and objective statements. They suggest that, in this specific case, values could outweigh the truth. The social component refers to the individual’s relationship to his or her social environment. People often turn to conspiracy beliefs when they see their positive external image challenged (Cichocka et al. 2016). This applies to people who tend to be on the losing side, who come from ethnically disadvantaged groups, and/or who feel victimized (Bilewicz et al. 2013) but also to narcissistically inclined people who are looking for confirmation of their exaggerated self-image (Cichocka et al. 2016). This leads to the hypotheses:

-

H_03: Conservation has a positive correlation with conspiracy beliefs.

-

H_04: Self-enhancement has a positive association with conspiracy beliefs.

-

H_05: Self-transcendence has a negative association with conspiracy beliefs.

Sociodemographic control variables

A systematic review by van Mulukom et al. (1982) found consistent positive associations between low education, income, and nonwhite ethnicity (in the US and UK) with stronger conspiracy beliefs. Age and sex inconsistently affected conspiracy beliefs across studies. In two representative surveys conducted by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, twice the proportion of conspiracy believers with an immigrant background in Germany compared to people without an immigrant background was found (Roose 2020). In addition, more people, at 9%, in East Germany (the territory of the former German Democratic Republic) stated that corona was a means of oppression, than those in West Germany (the territory of the Federal Republic of Germany until 1990), at 5% (Roose 2020). Hence, we decided to include birth country outside of Germany and residence in East Germany as covariates in the estimation.

Materials and methods

For the present analysis, data from an ongoing longitudinal survey of individuals living in private households were used, provided by the Leibnitz Institute for the Social Sciences (GESIS) (Bosnjak et al. 2018; GESIS 2021). Supplementary material, such as SPSS syntax and outputs or Mplus code, can be obtained at the following address: https://osf.io/kq78y/.

The GESIS panel is a probability-based mixed-mode access panel fielded every second month since 2013. Data collection was carried out by Kantar TNS, a German market and social research institute, following the standards of the International Code on Market, Opinion and Social Research and Data Analytics (International Chamber of Commerce and ESOMAR 2016). The participants provided their written informed consent for initial participation as well as subsequent panel participation. Ethical standards of the GESIS panel are explained in detail in the Rules for Safeguarding Good Scientific Practice (Wolf and Koch 2018).

When this study was conducted, the complete data set also included the results of the “GESIS Panel Special Survey on the Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak in Germany,” which was conducted among the online panel participants between March and September 2020 (GESIS Panel Team 2020). This additional survey contained questions about feelings, beliefs, and behaviors regarding COVID-19.

A path analysis with mediation test was conducted to examine the total, direct, and indirect effects of higher-order human values on COVID-19-related trust in institutions, the perceived threat of infection, evaluation of the effectiveness of containment measures, and the number of self-administered measures (Fig. 2).

Structural model of mediation analysis. Note: The figure presents the structural model of the mediation analysis of effects of higher-order values on COVID-19-related outcomes mediated through conspiracy beliefs. OC = Openness to change, SE = Self-enhancement, CO = Conservation, ST = Self-transcendence

We used Mplus 8.7 with full information maximum likelihood estimation (Muthén et al. 2016; Muthén and Muthén 1998–2020). To account for non-normal distributions, robust confidence intervals were estimated using 10,000 bootstrapping samples. Due to a saturated model, R2 values are reported as measures of model fit. Determining the statistical power of a mediation analysis is often challenging. Fritz and Mackinnon (2007) therefore provide precalculated scores that can be used to estimate statistical power from sample size. Under the most conservative conditions (complete mediation and small effect sizes (0.14) of both α- and β-paths), an empirical power of 0.80 can be obtained with 462 to 667 participants, which is well below the sample size of 4382 participants. Ordinal predictor variables (e.g., net monthly household income, level of education, origin) were transformed into binary-coded dummy variables and included as control variables, with the reference variables excluded.

Sample description

The whole dataset comprised 11,797 individuals. Questions about the participants’ corona conspiracy beliefs were asked of 4518 individuals around September 2020. Human values from the previous year (i.e., just before the pandemic outbreak) were included in the study, which limited the sample size to 4382. Individuals were aged 21 to 86, with a mean age of 55.51 (SD = 14.41, 50.5% female). In total, 4022 individuals (91.8%) were born in Germany, 213 in Europe (4.9%), and 57 (1.3%) outside of Europe; of these, 3259 (74.5%) reported living in West Germany, while 1114 (25.5%) reported living in the territory of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR). Higher-order values showed mean scores of 4.85 (SD = 0.68) for openness to change, 3.19 (SD = 0.84) for self-enhancement, 4.24 (SD = 0.91) for conservation, and 4.74 (SD = 0.68) for self-transcendence (see the full table with descriptive statistics in the supplementary material).

Construction of variables

Not all questions were included in every wave of the survey; for example, questions about human values were asked every year in and around September; COVID-19 items were asked only since March 2020, but every two months in each wave; three questions on corona conspiracy beliefs have occurred only once so far in September 2020. Following the Hyman–Tate conceptual timing criterion (Tate 2015), we took the measurements before the pandemic for the higher-order human values, while the items for COVID-19 conspiracies were queried during the pandemic.

To avoid confronting the survey participants with the 57-item measurement scale, the basic human values were measured with a 17-item, 6-point Likert scale where 1 denoted, “not like me at all,” and 6 meant, “very much like me.” The items each consisted of one statement about a person, describing what the person values (“it is important to her/him …”). The Schwartz Values Short Scale-4 was developed by the GESIS panel, and the items were chosen to match the four poles of the scale best. The reliability estimates were satisfactory (ω = 0.62 to 70) for the four higher-order values (GESIS 2021). For each of the four higher-order values, scale scores were computed by taking the mean of the basic human values belonging to this higher-order value (see Table 1).

According to the Coding & Analysis Instructions (Schwartz 2016), we used the uncentered values to compute the scale scores. The reliability was estimated with McDonald’s omega and ranged between ω = 0.640 for Conservation and ω = 0.784 for Openness to change with ω = 0.707 for Self-enhancement and ω = 0.693 for Self-transcendence. However, although these values are not excellent, they are common for psychometric short-scales. According to Rammstedt and Beierlein (2014), Cronbach’s alpha coefficients tend to underestimate the reliability of short-scale measures.

The GESIS panel provided four multi-item scales for the COVID-19-related outcomes (perceived threat of infection with the coronavirus, behavioral changes measured by the number of measures taken, beliefs in the effectiveness of public policy measures to mitigate the spread of the pandemic, and trust in politics and institutions) as well as a three-item scale for the intensity of coronavirus conspiracy beliefs.

Conspiracy beliefs about COVID-19 comprised three items (“I think the coronavirus is a biological weapon, which has been developed in secret governmental laboratories,” “…the coronavirus is used in order to restrict civil rights and to start an ongoing surveillance of citizens,” “…the danger and numbers regarding the coronavirus are purposely exaggerated”), each measured with a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree). All three have in common that someone else (secret governmental scientists, politicians, health institutions) is up to something that does not correspond to the mainstream information. The index was based on the mean of the three items (M = 2.47, SD = 1.46, ω = 0.85).

The perceived threat of infection was measured with five items, which asked about the estimated likelihood that the respondents will: (a) infect themselves; (b) someone close to them will become infected; that (c) the respondent will need to be hospitalized; or will (d) need to comply with quarantine measures in the next two months; and (e) that the participant will infect others. Responses were measured using a Likert scale, from 1 (not at all likely) to 7 (absolutely likely). We used the mean of the item scores to form the index (M = 3.31, SD = 1.01, ω = 0.87).

The evaluation of the effectiveness of the measures was built on seven questions about pandemic containment measures taken by the government. These included, for example, the closure of daycare centers, schools or restaurants, or curfews. The items were answered on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not effective at all) to 5 (very effective). Again, the mean value was used to form the scale score (M = 2.97, SD = 0.79, ω = 0.87).

The scale used to measure trust in politics and institutions included assessments of trust in nine political and health actors and institutions, which became important during the pandemic, such as, e.g., the city administrators, the federal government, the World Health Organization (WHO), or scientists. The scale value was again calculated from the mean of all nine items (M = 3.74, SD = 0.77, ω = 0.92).

Precautionary behavior as the number of measures taken to prevent an infection was measured with 10 dichotomous (0 = not mentioned; 1 = mentioned) items, such as “places avoided,” “quarantined because of/without symptoms,” or “face mask worn.” The scale score was formed from the sum of the mentioned measures (M = 5.01, SD = 1.70, ω = 0.66).

Sociodemographic variables such as sex, age, level of education, and household income were observed variables and are usually included as covariates to control for effects not resulting from the predictors.

Educational level and monthly household net income were categorized and aggregated into variables with three values each (low, medium, high). According to the Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt), the current official figures for Germany from 2018 assume an average net household income of €1925 and a median household income of €1733. They describe an income of less than 50% of the median income as very low, and an income of 200% or more of the median income as high (Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis) et al. 2021). Consequently, household income was classified into three groups: low income (< 900 €); middle income (900 to 3200 €); and high income (> 3200 €), according to the income classes provided by the GESIS panel.

No school-leaving certificate at all, a lower-secondary school grade (Hauptschule), or a degree from a polytechnic secondary school (GDR) were classified as a low-educational level. A secondary school certificate (Realschule) and a 10th grade diploma from a polytechnic secondary school (GDR) counted as a medium level of education, and an entrance qualification for a university or a university of applied sciences was classified as a high level of education. From both variables, education level and net monthly income, 0/1 dummy variables were formed. For the respondents’ country of birth, the panel asked whether they were born in Germany, another European country, or a non-European country. From this, as well as for gender and place of residence in East or West Germany, binary-coded dummy variables were formed.

Results

In the path analysis, we used a sequential design, i.e., human values were measured first, followed by conspiracy beliefs, and finally outcomes (see Table 2 for correlations).

This was to ensure that no interactions were included. However, since we are dealing with cross-sectional data, i.e., we are not examining a change in a value, we would like to emphasize that the term “effect” does not imply a causal relationship in the sense of “a change in variable X causes a change in variable y.” It rather expresses the statistical correlational relationship of the variables (Wu and Zumbo 2008). We report standardized total effects of higher-order human values on conspiracy beliefs and COVID-related outcomes and standardized direct and indirect effects mediated through conspiracy beliefs. Conspiracy beliefs were the strongest predictors of all four COVID-19-related outcomes, namely the assessment and implementation of containment measures, the assessment of perceived threat, and trust in the institutions and individuals involved while all four higher-order values showed a significant effect on conspiracy beliefs with self-transcendence the strongest. Table 3 presents all standardized direct effects of higher-order values and control variables on conspiracy beliefs and the four COVID-19-related outcomes. A partial mediation of the influence of self-transcendence via conspiracy beliefs on all four COVID-19-related measures could be proven.

Simultaneously, a partial mediation of openness to change via conspiracy beliefs could be detected for perceived threat and trust in institutions and individuals involved (Table 4).

The inclusion of covariates increased the explained variance for conspiracy beliefs from R2 = 0.039 to R2 = 0.147, for perceived threat from R2 = 0.050 to R2 = 0.064 for the number of measures taken from R2 = 0.099 to R2 = 0.128, for trust in institutions and persons involved from R2 = 0.319 to R2 = 0.342 and for the evaluation of the measures from R2 = 0.088 to R2 = 0.115 (see supplementary material).

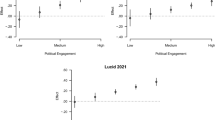

Exploratory findings

Residence in East Germany had a negative total effect on all four COVID-19-related outcomes. People born outside Europe showed a negative total effect on trust in people and institutions. People born outside Germany showed consistently negative indirect effects on all COVID-19-related outcomes, as did people who resided in East Germany. The coefficients for East Germans were approximately twice as strong in each case (Table 5). An independent samples t-test revealed significant differences between individuals living in East and West Germany for all COVID-19-related outcomes as well as for conspiracy beliefs. We used the Welch test statistic, which is robust to variance heterogeneity, for this purpose. In addition, the analysis of variance showed significant differences for conspiracy beliefs between individuals born in Germany and individuals born in foreign countries and regarding trust in politics and institutions between individuals born in Germany and people born in non-European countries (Fig. 3). Among higher-order human values, a significant difference was found only for conservation. Thus, people residing in East Germany rated conservative values significantly higher.

Discussion

The positive effect of self-enhancement on conspiracy beliefs made us accept hypothesis H_04. Conservation was the only higher-order value that did not have a total effect on any of the four COVID-19-related outcomes. However, taking conspiracy belief into account as the mediator variable, positive coefficients of direct effects became significant for three of the COVID-19-related outcomes, except for perceived threat of infection while all indirect effects were negative, which confirms the assumption of an ambiguous nature of conservation. Since a positive effect on conspiracy beliefs was found, hypothesis H_03 could be accepted. Individuals who valued self-transcendence rated infection risks as higher, rated interventions as more effective (indirectly via conspiracy beliefs), had significantly more trust in authorities and responsible individuals, and took more action to combat the pandemic, which led us to subsequently accept hypothesis H_01. The strong negative effect on conspiracy beliefs also made us accept hypothesis H_05.

The finding that conspiracy beliefs are negatively associated with all four COVID-19-related measures is in line with the pre-COVID results on similar issues as published by Oliver and Wood (2014a) and Jolley and Douglas (2014), suggesting that conspiracy beliefs negatively affect health decisions, confirming hypothesis H_02. The strongest effects were seen in the lower rating of the usefulness of the measures and the significantly lower perceived trust in the institutions and persons involved.

Although respondents’ country of birth did not directly influence the COVID-19-related outcomes (unlike residence in East or West Germany), both indirectly affected outcomes via conspiracy beliefs (Table 5). This is an indication that country of origin could have an influence on COVID-19-related outcomes that would not have been detected if conspiracy beliefs had not been part of the study as a mediator variable. Looking at the standardized total effects of origin and place of residence in Germany, it is striking that the differences between West and East Germans with respect to conspiracy beliefs are stronger (and significant) than the differences between those born in Germany and those born abroad. The higher-order values from the anxiety-free growth hemisphere (see Fig. 1) provided the most evident effects. In contrast, the effects of higher-order values from the anxiety-avoidance hemisphere (conservation, self-enhancement) were not consistent and had positive indirect effects when negative direct effects were present and vice versa.

One of the COVID-19-related dependent variables was trust in institutions and individuals involved. One assumption of the present study was that the expression of values and conspiracy beliefs influence how this kind of trust was perceived. After all, trust was related to those institutions and individuals involved in making decisions about actions and communicating them during the pandemic. The perception of trust in institutions and individuals involved thus temporally lagged behind the beginning of the pandemic. Even though there is evidence in the literature that conspiracy belief is an antecedent of trust in institutions and individuals involved (Pavela Banai et al. 2022; Karić and Međedović 2021; Pummerer et al. 2022), there are also studies that assume the opposite direction of action (Bruder and Kunert 2022; Eberl et al. 2021). Consequently, even though the relationship between these two constructs are closely intertwined, it may not be possible to clarify which is the antecedent and the consequent clearly. More research is needed to elucidate this question in an experimental design. Basically, for the sake of completeness, it should be mentioned that in any correlational mediation analysis, no matter how sound the theoretical derivation, other alternative models as well as additional variables not yet investigated are possible (see Wu and Zumbo (2008) and Fiedler et al. (2018) for a comprehensive view).

Bonetto et al. (2021) and Bojanowska et al. (2021) examined the change in values due to the impact of the pandemic. In both studies, the changes were very small, while the sign of the correlation coefficient, however, remained constant. However, to avoid a possible interaction effect, the values variables were measured before the pandemic, and the variables of conspiracy beliefs and the COVID-related outcomes were measured later. This sequential procedure is also consistent with the necessary Hyman–Tate criterion for mediation analyses, according to which the putative predictor variables must be temporally antecedent to the putative outcomes. In addition, while basic human values form during adolescence, the specific attitudes toward COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs could only form in young adulthood at the earliest, since all individuals in the sample are already at least 21.

There is widespread agreement in the prevailing literature that perceived threat and loss of control are possible causes for adopting conspiracy beliefs (Douglas et al. 2019; van Prooijen and Acker 2015). The present paper also builds on this argument. However, this assumption might be challenged by two studies from recent years. Concerning “lack of control” the authors could not find a significant effect on general conspiracy theories, but they write that “the predicted effect of control was more likely to be observed when beliefs were measured in terms of specific conspiracy theories, rather than as general or abstract claims” (Stojanov and Halberstadt 2020). The present article investigates specific conspiracy beliefs in the corresponding context (COVID-19). The authors also write, “In fact, it appears that the correlational evidence for a negative link between feelings of control and conspiracy beliefs is more robust than the experimental evidence” (Stojanov and Halberstadt 2020). The present study is purely correlational. Therefore, the findings of Stojanov and Halberstadt (2020) are more applicable to experimental designs with general conspiracy beliefs. Regarding “anxiety, uncertainty aversion, and threat” the authors indeed found “that people who were, on average, more anxious, uncertainty averse, and existentially threatened held stronger conspiracy beliefs” (Liekefett et al. 2023). Only in the opposite direction could no effect be proven—but this was irrelevant for the present study. Therefore, both articles ultimately support our derivation of conspiracy beliefs.

It is worth noting that we did not distinguish between different types of conspiracy theories when designing this study. As per, for example, Nera et al. (2021) despite the diversity of conspiracy theories, they are sometimes seen as a single, homogenous phenomena. There is a proposal to distinguish between believing in upward conspiracy theories and downward conspiracy ideas using traditional conspiracy theorizations. The former are hypothesized to be beliefs that challenge authority, while the latter are hypothesised to be supported by conservative ideology. Based on that distinction, we believe the findings of this paper to be applicable to upward conspiracy theories mostly, while the downward conspiracy theories still require more research in this respect. This may also be due to the nature of the specific conspiracy beliefs in question. The three components that constitute the conspiracy beliefs of the present study (“I think the coronavirus is a biological weapon, which has been developed in secret governmental laboratories,” “…the coronavirus is used in order to restrict civil rights and to start an ongoing surveillance of citizens,” “…the danger and numbers regarding the coronavirus are purposely exaggerated”) all target authorities and supposed elites.

Obviously, any discussion on various phenomena connected with conspiracy theories ultimately faces the very challenge of treading carefully on the side of the facts and not opinions (Brotherton and Son 2021). This leads to the issue of a metacognitive labeling of various claims. While this has not been within the scope of the paper, we understand that what exactly is truth at any given time, what is just another opinion, and what is ultimately made-up stories, is always known only after the fact. However, we have to make assumptions regarding what is a conspiracy theory. Otherwise, one could claim to any evidence, no matter how good, that it is false, one only has to wait long enough until the opposite is proven. This is possibly a potential area for future research.

A limitation of this study is the restricted availability of data for the relevant period. The standard edition of the GESIS panel only records whether the participant resides in East or West Germany (GESIS 2021). A more precise determination of the place of residence (at least by state) could be possible in the extended version. To examine this, however, one had to be on-site at the data center. So, here, the fear of data privacy violations may distort results, since only east/west differences can be examined, but the true differences are possibly to be found in the north/south divide. Furthermore, there is the issue of the low reliability of the short scale for recording human values. The GESIS panel records human values with 17 items, while the current version of the PVQ-57 uses 57 items (Schwartz et al. 2012b). Not only are more questions asked here, but the GESIS questions are also slightly modified. However, the scale was developed to measure the values in the best possible way (GESIS 2021).

Conclusion

Because of their persistence and association with resistance to advisable behavior, not just during the COVID pandemic, conspiracy beliefs and their associations have harmed challenges of controlling the coronavirus pandemic and pose a risk for similar situations in the future. To increase acceptance of scientifically accepted efforts in better governance, it will be necessary for scientists and policymakers to challenge these conspiracy narratives. The results of this study can improve the ability to develop and enforce policies. This article has shown that belief in conspiracy narratives reveals associations of higher-order values with all four COVID-19-related measures that would not have been apparent without this mediator. In doing so, it contributes to the understanding of how pandemic mitigation measures are implemented differently. We were able to demonstrate a partial mediation of the influence of self-transcendence via conspiracy beliefs on all four COVID-19-related measures, the assessment and implementation of containment measures, the assessment of perceived threat, and trust in the institutions and individuals involved. A partial mediation of openness to change via conspiracy beliefs could be detected for perceived threat and trust in institutions and individuals involved. Our results suggest that human values, conspiracy beliefs, and the consequences of the pandemic should be further examined in a long-term context as well as in experimental studies to reveal and confirm possible cause–effect relationships. Moreover, values could contribute to the formation of conspiracy beliefs and indirectly affect COVID-19-related attitudes and behaviors through them. This finding enriches the research on conspiracy beliefs as well as epidemiology. However, more research is needed to examine the relationship of conspiracy beliefs, values, and human behavior. This includes comparative studies with other countries and also the contribution of other psychometric variables.

Data availability

Due to data protection restrictions, access to the data can only be provided to registered users of the GESIS panel, available at Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften, Mannheim. Scientific use is free of charge and can be requested at: https://www.gesis.org/gesis-panel/data

The analysis scripts used for this article can be accessed at: https://osf.io/kq78y/.

References

Abalakina‐Paap M, Stephan WG, Craig T, Gregory WL (1999) Beliefs in conspiracies. Polit Psychol 20(3):637–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00160

Bilewicz M, Winiewski M, Kofta M, Wójcik A (2013) Harmful ideas, the structure and consequences of anti-semitic beliefs in Poland. Polit Psychol 34(6):821–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12024

Bilsky W, Janik M, Schwartz SH (2011) The structural organization of human values-evidence from Three Rounds of the European Social Survey (ESS). J Cross Cult Psychol 42(5):759–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110362757

Bojanowska A, Kaczmarek ŁD, Koscielniak M, Urbańska B (2021) Changes in values and well-being amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. PLoS One 16(9):e0255491. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255491

Bonetto E, Dezecache G, Nugier A, Inigo M, Mathias J-D, Huet S, Pellerin N, Corman M, Bertrand P, Raufaste E, Streith M, Guimond S, La Sablonnière R de, Dambrun M (2021) Basic human values during the COVID-19 outbreak, perceived threat and their relationships with compliance with movement restrictions and social distancing. PloS one 16(6):e0253430. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253430

Bosnjak M, Dannwolf T, Enderle T, Schaurer I, Struminskaya B, Tanner A, Weyandt KW (2018) Establishing an open probability-based mixed-mode panel of the general population in Germany. Soc Sci Comput Rev 36(1):103–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439317697949

Brotherton R, Son LK (2021) Metacognitive labeling of contentious claims: facts, opinions, and conspiracy theories. Front Psychol 12:644657. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.644657

Bruder M, Haffke P, Neave N, Nouripanah N, Imhoff R (2013) Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in conspiracy theories across cultures: conspiracy mentality questionnaire. Front Psychol 4(225)

Bruder M, Kunert L (2022) The conspiracy hoax? Testing key hypotheses about the correlates of generic beliefs in conspiracy theories during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Psychol 57(1):43–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12769

Calvillo DP, Ross BJ, Garcia RJB, Smelter TJ, Rutchick AM (2020) Political ideology predicts perceptions of the threat of COVID-19 (and susceptibility to fake news about it). Social Psychol Personal Sci 11(8):1119–1128. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620940539

Caprara GV, Schwartz SH, Vecchione M, Barbaranelli C (2008) The personalization of politics. Eur Psychol 13(3):157–172. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.13.3.157

Cichocka A, Marchlewska M, de Zavala AG (2016) Does self-love or self-hate predict conspiracy beliefs? narcissism, self-esteem, and the endorsement of conspiracy theories. Social Psychol Personal Sci 7(2):157–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615616170

Cieciuch J, Davidov E, Vecchione M, Beierlein C, Schwartz SH (2014) The cross-national invariance properties of a new scale to measure 19 basic human values. J Cross Cult Psychol 45(5):764–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022114527348

Douglas KM (2021) COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Group Process Intergroup Relat 24(2):270–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220982068

Douglas KM, Sutton RM, Cichocka A (2017) The psychology of conspiracy theories. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 26(6):538–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417718261

Douglas KM, Uscinski JE, Sutton RM, Cichocka A, Nefes T, Ang CS, Deravi F (2019) Understanding conspiracy theories. Polit Psychol 40(S1):3–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12568

Eberl J-M, Huber RA, Greussing E (2021) From populism to the “plandemic”: why populists believe in COVID-19 conspiracies. J Elect Public Opin Parties 31(sup1):272–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2021.1924730

Enea V, Eisenbeck N, Carreno DF, Douglas KM, Sutton RM, Agostini M, Bélanger JJ, Gützkow B, Kreienkamp J, Abakoumkin G, Abdul Khaiyom JH, Ahmedi V, Akkas H, Almenara CA, Atta M, Bagci SC, Basel S, Berisha Kida E, Bernardo ABI, Buttrick NR, Chobthamkit P, Choi H-S, Cristea M, Csaba S, Damnjanovic K, Danyliuk I, Dash A, Di Santo D, Faller DG, Fitzsimons G, Gheorghiu A, Gómez Á, Grzymala-Moszczynska J, Hamaidia A, Han Q, Helmy M, Hudiyana J, Jeronimus BF, Jiang D-Y, Jovanović V, Kamenov Ž, Kende A, Keng S-L, Kieu TTT, Koc Y, Kovyazina K, Kozytska I, Krause J, Kruglanski AW, Kurapov A, Kutlaca M, Lantos NA, Lemay EP, Lesmana CBJ, Louis WR, Lueders A, Malik NI, Martinez A, McCabe KO, Mehulić J, Milla MN, Mohammed I, Molinario E, Moyano M, Muhammad H, Mula S, Muluk H, Myroniuk S, Najafi R, Nisa CF, Nyúl B, O’Keefe PA, Osuna JJO, Osin EN, Park J, Pica G, Pierro A, Rees J, Reitsema AM, Resta E, Rullo M, Ryan MK, Samekin A, Santtila P, Sasin E, Schumpe BM, Selim HA, Stanton MV, Sultana S, Tseliou E, Utsugi A, van Breen JA, van Lissa CJ, van Veen K, vanDellen MR, Vázquez A, Wollast R, Yeung VW-L, Zand S, Žeželj IL, Zheng B, Zick A, Zúñiga C, Leander NP (2023) Intentions to be vaccinated against COVID-19: the role of prosociality and conspiracy beliefs across 20 countries. Health Commun 38(8):1530–1539. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2021.2018179

Farrell T, Piccolo L, Perfumi SC, Mensio M, Alani H (2019) Understanding the Role of Human Values in the Spread of Misinformation. In: Proceedings of the Conference for Truth and Trust Online 2019. TTO Conference Ltd

Fiedler K, Harris C, Schott M (2018) Unwarranted inferences from statistical mediation tests – an analysis of articles published in 2015. J Exp Soc Psychol 75:95–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.11.008

Freeman D, Waite F, Rosebrock L, Petit A, Causier C, East A, Jenner L, Teale A-L, Carr L, Mulhall S, Bold E, Lambe S (2022) Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs, mistrust, and compliance with government guidelines in England. Psychol Med 52(2):251–263. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001890

Fritz MS, Mackinnon DP (2007) Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol Sci 18(3):233–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x

Georgiou N, Delfabbro P, Balzan R (2020) COVID-19-related conspiracy beliefs and their relationship with perceived stress and pre-existing conspiracy beliefs. Personality Individ Differ 166:110201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110201

GESIS (2021) GESIS Panel - Standard Edition. GESIS Data Archive

GESIS Panel Team (2020) GESIS Panel Special Survey on the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Germany. GESIS Data Archive

Gligorić V, da Silva MM, Eker S, van Hoek N, Nieuwenhuijzen E, Popova U, Zeighami G (2021) The usual suspects: how psychological motives and thinking styles predict the endorsement of well-known and COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs. Appl Cognit Psychol 35(5):1171–1181. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3844

Gómez-Ochoa SA, Franco OH (2020) COVID-19: facts and failures, a tale of two worlds. Eur J Epidemiol 35(11):991–994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-020-00692-7

Goreis A, Voracek M (2019) A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological research on conspiracy beliefs: field characteristics, measurement instruments, and associations with personality traits. Front Psychol 10(205). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00205

Grzesiak-Feldman M (2013) The effect of high-anxiety situations on conspiracy thinking. Curr Psychol 32(1):100–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-013-9165-6

Homer PM, Kahle LR (1988) A structural equation test of the value-attitude-behavior hierarchy. J Pers Soc Psychol 54(4):638–646. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.4.638

Huang L, Li OZ, Wang B, Zhang Z (2022) Individualism and the fight against COVID-19. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01124-5

Hughes S, Machan L (2021) It’s a conspiracy: Covid-19 conspiracies link to psychopathy, Machiavellianism and collective narcissism. Person Individ Differ 171:110559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110559

Imhoff R, Bruder M (2014) Speaking (un–)truth to power: conspiracy mentality as a generalised political attitude. Eur J Pers 28(1):25–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1930

Imhoff R, Lamberty PK (2017) Too special to be duped: Need for uniqueness motivates conspiracy beliefs. Eur J Soc Psychol 47(6):724–734. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2265

International Chamber of Commerce, ESOMAR (2016) International code on market, opinion and social research and data analytics. https://esomar.org/code-and-guidelines/icc-esomar-code. Accessed 31 March 2022

Jolley D, Douglas KM (2014) The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PLoS ONE 9(2):e89177. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089177

Jolley D, Douglas KM, Leite AC, Schrader T (2019) Belief in conspiracy theories and intentions to engage in everyday crime. Br J Soc Psychol 58(3):534–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12311

Karić T, Međedović J (2021) Covid-19 conspiracy beliefs and containment-related behaviour: the role of political trust. Person Individ Differ 175:110697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110697

Knafo A, Roccas S, Sagiv L (2011) The value of values in cross-cultural research: a special issue in Honor of Shalom Schwartz. J Cross-Cult Psychol 42(2):178–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110396863

Kuhn SAK, Lieb R, Freeman D, Andreou C, Zander-Schellenberg T (2021) Coronavirus conspiracy beliefs in the German-speaking general population: endorsement rates and links to reasoning biases and paranoia. Psychol Med:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001124

Lantian A, Muller D, Nurra C, Douglas KM (2017) I know things they don’t know! Social Psycho 48(3):160–173. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000306

Latkin CA, Dayton L, Moran M, Strickland JC, Collins K (2021) Behavioral and psychosocial factors associated with COVID-19 skepticism in the United States. Curr Psychol:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01211-3

Liekefett L, Christ O, Becker JC (2023) Can conspiracy beliefs be beneficial? Longitudinal linkages between conspiracy beliefs, anxiety, uncertainty aversion, and existential threat. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 49(2):167–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672211060965

Marinthe G, Brown G, Delouvée S, Jolley D (2020) Looking out for myself: exploring the relationship between conspiracy mentality, perceived personal risk, and COVID-19 prevention measures. Br J Health Psychol 25(4):957–980. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12449

Moosa S, Abdul Raheem R, Riyaz A, Musthafa HS, Naeem AZ (2022) The role of social value orientation in modulating vaccine uptake in the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Human Social Sci Commun 9(1):467. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01487-9

Motta M, Goren P (2021) Basic human values & compliance with government-recommended prosocial health behavior. J Elect Public Opin Parties 31(sup1):206–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2021.1924726

Muthén BO, Muthén LK, Asparouhov T (2016) Regression and mediation analysis using Mplus. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Muthén LK, Muthén B (1998–2020) Mplus User’s Guide: Version 8, 8th edn. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Nera K, Wagner-Egger P, Bertin P, Douglas KM, Klein O (2021) A power-challenging theory of society, or a conservative mindset? Upward and downward conspiracy theories as ideologically distinct beliefs. Eur J Soc Psychol 51(4–5):740–757. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2769

Oliver JE, Wood TJ (2014a) Conspiracy theories and the paranoid style(s) of mass opinion. Am J Pol Sci 58(4):952–966. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12084

Oliver JE, Wood TJ (2014b) Medical conspiracy theories and health behaviors in the United States. JAMA Intern Med 174(5):817–818. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.190

Parks L, Guay RP (2009) Personality, values, and motivation. Pers Individ Differ 47(7):675–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.06.002

Pavela Banai I, Banai B, Mikloušić I (2022) Beliefs in COVID-19 conspiracy theories, compliance with the preventive measures, and trust in government medical officials. Curr Psychol 41(10):7448–7458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01898-y

Pivetti M, Melotti G, Bonomo M, Hakoköngäs E (2021) Conspiracy beliefs and acceptance of COVID-vaccine: an exploratory study in Italy. Social Sci 10(3):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10030108

Pivetti M, Paleari FG, Barni D, Russo C, Di Battista S (2023) Self-transcendence values, vaccine hesitancy, and COVID-19 vaccination: some results from Italy. Social Influence 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2023.2261632

Poier S, Nikodemska‐Wołowik AM, Suchanek M (2022) How higher‐order personal values affect the purchase of electricity storage—Evidence from the German photovoltaic market. J Cons Behaviour. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.2048

Ponizovskiy V, Ardag M, Grigoryan L, Boyd R, Dobewall H, Holtz P (2020) Development and validation of the personal values dictionary: a theory-driven tool for investigating references to basic human values in text. Eur J Pers 34(5):885–902. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2294

Pummerer L, Böhm R, Lilleholt L, Winter K, Zettler I, Sassenberg K (2022) Conspiracy theories and their societal effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Psychol Person Sci 13(1):49–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211000217

Rammstedt B, Beierlein C (2014) Can’t We Make It Any Shorter? J Individ Differ 35(4):212–220. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000141

Rokeach M (1969) Beliefs attitudes and values. A theory of organization and change. Jossey-Bass behavioral science series. Jossey-Bass Inc. Publ, San Francisco

Roose J (2020) Verschwörung in der Krise: Repräsentative Umfragen zum Glauben an Verschwörungstheorien vor und in der Corona-Krise, Berlin

Sagiv L, Roccas S (2021) How do values affect behavior? Let me count the ways. Personality and social psychology review an official journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/10888683211015975

Saroglou V (ed) (2014) Religion, personality, and social behavior. Psychology Press, New York

Schwartz SH (1999) A theory of cultural values and some implications for work. Appl Psychol Int Rev 48(1):23–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1999.tb00047.x

Schwartz SH (2012a) An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values. Online Read Psychol Cult 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1116

Schwartz SH (2016) Coding and analyzing PVQ-RR data (instructions for the revised Portrait Values Questionnaire). Unpublished

Schwartz SH (2017) The refined theory of basic values. In: Roccas S, Sagiv L (eds) Values and behavior: taking a cross cultural perspective. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 51–72

Schwartz SH, Bilsky W (1987) Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. J Pers Soc Psychol 53(3):550–562. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.3.550

Schwartz SH, Bilsky W (1990) Toward a theory of the universal content and structure of values: extensions and cross-cultural replications. J Pers Soc Psychol 58(5):878–891. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.5.878

Schwartz SH, Caprara GV, Vecchione M (2010) Basic personal values, core political values, and voting: a longitudinal analysis. Adv Polit Psychol 31(3):421–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00764.x

Schwartz SH, Cieciuch J, Vecchione M, Davidov E, Fischer R, Beierlein C, Ramos A, Verkasalo M, Lönnqvist J-E, Demirutku K, Dirilen-Gumus O, Konty M (2012) Refining the theory of basic individual values. J Pers Soc Psychol 103(4):663–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029393

Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis), Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB), Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung (BiB) (2021) Datenreport 2021: Ein Sozialbericht für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn

Stojanov A, Halberstadt J (2020) Does lack of control lead to conspiracy beliefs? A meta-analysis. Eur J Soc Psychol 50(5):955–968. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2690

Swami V (2012) Social psychological origins of conspiracy theories: the case of the jewish conspiracy theory in malaysia. Front Psychol 3:280. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00280

Swami V, Furnham A (2012) Examining conspiracist beliefs about the disappearance of Amelia Earhart. J Gen Psychol 139(4):244–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2012.697932

Swami V, Furnham A, van Prooijen J-W (2014a) Political paranoia and conspiracy theories. In: van Prooijen J-W, van Lange PAM (eds) Power, politics, and paranoia: Why people are suspicious of their leaders. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 218–236

Swami V, Voracek M, Stieger S, Tran US, Furnham A (2014b) Analytic thinking reduces belief in conspiracy theories. Cognition 133(3):572–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2014.08.006

Swami V, Weis L, Lay A, Barron D, Furnham A (2016) Associations between belief in conspiracy theories and the maladaptive personality traits of the personality inventory for DSM-5. Psychiat Res 236:86–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.12.027

Tate CU (2015) On the overuse and misuse of mediation analysis: it may be a matter of timing. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 37(4):235–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2015.1062380

Torres CV, Longo CA, Macedo FGL, Faiad C (2023) COVID-19 vaccination in Brazilian public security agents: are human values good predictors? PIJPSM 46(2):293–308. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-07-2022-0093

van Mulukom V, Pummerer LJ, Alper S, Bai H, Čavojová V, Farias J, Kay CS, Lazarevic LB, Lobato EJC, Marinthe G, Pavela Banai I, Šrol J, Žeželj I (2022) Antecedents and consequences of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: A systematic review. Social Sci Med 301:114912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114912

van Prooijen J-W (2020) An existential threat model of conspiracy theories. Eur Psychol 25(1):16–25. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000381

van Prooijen J-W, Acker M (2015) The influence of control on belief in conspiracy theories: conceptual and applied extensions. Appl Cognit Psychol 29(5):753–761. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3161

Viskupič F, Wiltse DL, Meyer BA (2022) Trust in physicians and trust in government predict COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Social Sci Q 103(3):509–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.13147

Witte EH, Stanciu A, Boehnke K (2020) A new empirical approach to intercultural comparisons of value preferences based on Schwartz’s theory. Front Psychol 11:1723. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01723

Wolf C, Koch G (2018) Rules for Safeguarding Good Scientific Practice. https://www.gesis.org/fileadmin/upload/institut/leitbild/Gute_Praxis_GESIS_engl.pdf. Accessed 31 March 2022

Wolf LJ, Haddock G, Manstead ASR, Maio GR (2020) The importance of (shared) human values for containing the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Soc Psychol 59(3):618–627. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12401

Wu AD, Zumbo BD (2008) Understanding and using mediators and moderators. Soc Indic Res 87(3):367–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9143-1

Zhao J, Hahn U, Osherson D (2014) Perception and identification of random events. Journal of experimental psychology. Human Percept Perform 40(4):1358–1371. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036816

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Stefan Poier: conception and design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript drafting and revising, approval of final version for submission.

Michał Suchanek: conception and design, manuscript drafting and revising, approval of final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This article uses panel data and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed directly by any of the authors. Data collection was carried out by Kantar TNS, a German market and social research institute, following the standards of the International Code on Market, Opinion and Social Research and Data Analytics (International Chamber of Commerce & ESOMAR, 2016).

Patient consent statement

All participants provided their written informed consent for panel participation. Ethical standards of the GESIS panel are explained in detail in the Rules for Safeguarding Good Scientific Practice (Wolf & Koch 2018): https://www.gesis.org/fileadmin/upload/institut/leitbild/Gute_Praxis_GESIS_engl.pdf

Conflicts of interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Poier, S., Suchanek, M. The effects of higher-order human values and conspiracy beliefs on COVID-19-related behavior in Germany. J Public Health (Berl.) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-024-02210-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-024-02210-5