Abstract

Aim

To explore the factors associated with the coping styles in medical staff while providing emergency aid during public health emergencies.

Subject and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted to investigate medical and nursing staff members from four hospitals in Zhejiang Province who participated in emergency assistance in Shanghai during the Omicron pandemic in April 2022.

Results

Sixty-nine out of 74 subjects completed the questionnaire. Stepwise multivariate linear regression analysis revealed that psychological resilience (β = 0.30, 95% CI: 0.30, 1.08, p = 0.001) and social support (β = 0.26, 95% CI: 0.06, 2.01, p = 0.039) were correlated with positive coping (β = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.21, 0.57, p < 0.001), and friend support (β = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.28, 1.02, p = 0.001) significantly influenced positive coping.

Conclusion

Social support and psychological resilience are the main factors associated with the coping styles of medical staff. Tenacity and friend support are the main additional influencing factors for positive coping.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Public health emergencies refer to emergencies that occur suddenly and cause or may cause many casualties, property losses, ecological environmental damage, and serious social harm, thus endangering public security (Khan et al. 2018). Since the beginning of December 2019, the outbreak of COVID-19 has led to an epidemic. This public health emergency has been effectively controlled through effective isolation and treatment (Fenollar et al. 2021). In November 2021, the Omicron mutant was first found in South Africa, and has the characteristics of stronger transmission capacity, faster transmission (Saxena et al. 2022), and higher risk of repeated infection (Liu et al. 2022). Since the outbreak of the epidemic in Shanghai in early April, a number of medical personnel have been dispatched from all over the country to participate in assisting Shanghai.

The medical and nursing population is a special occupational group. In a special occupational environment, medical and nursing personnel treat people with certain physical and psychological problems (Sun et al. 2022). The infection rate of staff at the anti-epidemic front line is high (Wang et al. 2020), especially the medical staff who are responsible for treating and nursing infected patients in shelters. Due to the type of working environment, the nature of the work and the nursing objectives, medical personnel are under constant pressure. Therefore, medical staff are prone to anxiety and negative emotions due to this continuous pressure, which affects their ability to positively cope while working. A previous study showed that hospital managers were very anxious about the risk of infection during the outbreak, which may have caused serious mental problems (Zhang et al. 2021). In addition, social support can mitigate the adverse effects of stress on physical and mental health. Social support and a positive coping style enable medical staff to maintain stable mental health, face problems correctly, and have more courage to meet challenges (Saedpanah et al. 2016). Therefore, the stable mood and psychological state of medical staff play a key role in guiding the mentality of patients (Alghamdi 2016; Lian et al. 2021; Xie et al. 2021).

The purpose of this study is to assess the relationships among social support, psychological resilience, and positive coping among medical staff while providing emergency assistance in Taizhou, China.

Methods

Study design and participants

In April 2022, we adopted the cluster convenience sampling method to study the medical staff from four hospitals on the Zhejiang Province medical team that was sent to assist Shanghai. According to the particularity of the epidemic prevention and control work, with the active cooperation of all units, the survey subjects are trained in a unified way through tactical meetings before the start of the research investigation to ensure the authenticity, accuracy, and standardization of the data. An anonymous cross-sectional population-based online survey was conducted via the WeChat-incorporated Wen–Juan–Xing platform (Changsha Ranxing Information Technology Co., Ltd., Hunan, China). The questions raised in the completion process were answered in a timely manner, and anonymous responses were returned after completion. This study was approved by the Taizhou Hospital Committee of Zhejiang Province (K20220402).

Measurements

The self-designed general information questionnaire included items for gender, age, length of service and experience, education, professional title, marital status, family members' status, personnel relations, work experience in emergencies, severe, infection, respiratory and other critical diseases in the early stage of providing aid in Shanghai, experience in participating in epidemic prevention in the past 3 years, and participation in nucleic acid collection in the past 3 months.

Zung's Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS): SAS was developed by William W.K. Zung in 1971 (Dunstan and Scott 2020). This scale contains 20 items, including 15 positive scores and five negative scores. Each question is scored ranging from 1 (none or few times) to 4 (most or all times). A cut-off score above 45 points indicates anxiety (Zung 1971). The higher the SAS score, the more obvious the anxiety tendency of the patients. This study's total postanalysis Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.931 (Dunstan and Scott 2020).

The Psychological Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): the CD-RISC was developed by American psychologists Connor and Davidson in 2003. This scale comprises 25 items over three metrics (tenacity, strength, and optimism) that assess resilience or capacity to change and to cope with adversity. The Likert 5-level scoring is adopted, and the scoring range of each item is from 0 to 4 points: 0 for completely incorrect scoring, 1 for rarely correct scoring, 2 for sometimes correct scoring, 3 for usually correct scoring, and 4 for almost all times. The total score ranges from 0 to 100. A higher score indicates better resilience. This study's total postanalysis Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.912, which indicated good reliability and validity for clinical practice (Kuiper et al. 2019).

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS): the MSPSS, developed by Zimet et al., modified by Jiang Qianjin, evaluates the respondents’ perceived level of support that they received from their social network. This tool comprises 12 items that assess social support from family, friends, and significant others. Participants used a seven-point Likert response format (1 = ‘very strongly disagree’ to 7 = ‘very strongly agree’) to rate these items. The total scores range from 12 to 84, with higher scores indicating greater total perceived social support from all three sources. The total postanalysis Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the MSPSS in this study was 0.953 (Pushkarev et al. 2020).

Simple coping style questionnaire (SCSQ): the questionnaire was prepared by Xie Yaning in 1998. The simple coping style questionnaire consists of two dimensions (subscale), positive coping and negative coping, including 20 items, which can effectively reflect the possible coping tendencies when people are stimulated by external stimuli (Shigemura et al. 2020). The scale scores "0/1/2/3" corresponded to "not/occasionally/sometimes/often". The positive response dimension consists of items 1–12, which mainly reflect the characteristics of positive response. The negative coping dimension consists of items 13–20, which mainly reflect the characteristics of negative coping. This study will also adopt the positive response part of this questionnaire. The postanalysis Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of positive coping dimensions in this study was 0.880.

Statistical methods

This study utilized SPSS 22.0 software for data analysis. Data are described by the number of cases and percentage (%), and the chi-square (X2) test was used for comparisons between groups. The measurement data conforming to the normal distribution were described by the mean with standard deviation, and the comparison between the two groups was performed with a t test. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to analyse the correlation between coping style and anxiety, psychological resilience, and social support. Stepwise multiple linear regression analysis was used to explore the influencing factors of coping styles. P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance.

Results

In this study, a total of 74 medical staff completed the survey, with 93.4% of responses (69/74) being valid. The study samples included 57 women and 12 men. The average age was 34.68 ± 5.44 years. The proportion of respondents with experience in fighting COVID-19 was 47.8%.

Univariate analysis revealed that positive coping was not significantly better among sex (t = 1.776, p = 0.080), age (t = 0.495, p = 0.622), total service time (t = 0.580, p = 0.564), education level (F=0.810, p = 0.449), professional title (F=0.294, p = 0.746), experience treating COVID-19 patients (t = 0.217, p = 0.829), or experience in nucleic acid sampling (t = −0.510, p = 0.612) (Table 1).

Positive relationships were found between positive coping and psychological resilience (r = 0.725, p < 0.001), tenacity (r = 0.719, p < 0.001), strength (r = 0.682, p < 0.001), optimism (r = 0.609, p < 0.001), social support (r = 0.680, p < 0.001), family support (r = 0.604, p < 0.001), friend support (r = 0.688, p < 0.001), and significant other support (r = 0.593, p < 0.001), as shown in Table 2.

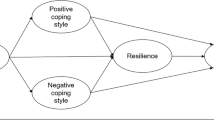

Based on the results of the univariate Pearson correlation analysis, we included the variables of anxiety, psychological resilience, tenacity, strength, optimism, social support, family support, friend support, and significant other support into the stepwise multivariate linear regression analysis. The results revealed that social support (β = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.08, 0.35, p = 0.003) and psychological resilience (β = 0.49, 95% CI: 0.12, 0.31, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with positive coping (Table 3, Model 1), and tenacity (β = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.21, 0.57, p < 0.001) and friend support (β = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.28, 1.02, p = 0.001) were significantly associated with positive coping (Table 3, Model 2).

Discussion

The results of this study show that social support and psychological resilience are the influencing factors of the coping styles of medical staff, among which tenacity and friend support are the main additional influencing factors.

The outbreak of COVID-19 was sudden and resulted in serious social harm, and the outbreak has had serious impacts on all areas of society (Zhou et al. 2020). The front-line medical staff face many negative situations and need a high level of psychological resilience to cope with the mental state brought about by these negative situations (Kartal et al. 2022). There is an urgent need for intervention measures aimed at nurses' active responses to reduce their perception of pressures and improve their psychological resilience. Self-confidence, calmness, relaxation, and openness are positive contributors to nurses' emotional stability, and are strategies for coping with and dealing with immediate stressors and for enhancing psychological resilience (Sun et al. 2020). To address public health emergencies, medical institutions all over the country are actively involved in epidemic prevention and control. The psychological pressure of medical staff at the forefront of epidemic prevention has increased dramatically, especially for nurses and women (Lai et al. 2020; Shanafelt et al. 2020). If the negative emotions of individuals are not effectively alleviated, they will escalate into group negative emotions, which will seriously affect social stability (Shigemura et al. 2020). Therefore, the psychological state of medical staff during emergency assistance in public health emergencies should not be ignored. The results of this study will be one of the important contributions to the success of future emergency assistance and will certainly provide a strong boost for the smooth development of future emergency assistance team management.

Social support refers to the act of providing protection for individuals who are experiencing stress from external causes. Social support can alleviate the negative impact of pressure on people, and it also requires individuals to further help themselves to alleviate the negative impact of pressure by utilizing corresponding coping methods (Wang et al. 2021). The statistically significant correlation analysis results of positive coping and social support show that positive coping is positively related to social support. Consistent with previous studies (Feng and Yin 2021; Labrague 2021), the more social support (including care, comfort, support, and help from relatives and friends) the nurse receives, the more she uses support, and the more she tends to adopt a positive coping style. One study showed that support from friends, family, leaders, and society can help relieve the work pressure of medical staff and help them to establish a sense of support and an active attitude to coping with pressure (Herbert et al. 2018). Consistent with this study, another study (Cooper et al. 2021) confirmed that the higher the level of support of friends, the more doctors and nurses will tend to adopt a positive coping style to deal with problems. Therefore, in the case of public health emergencies, we can encourage medical staff to obtain support and help from friends or relatives, maintain good relations, and improve their social support level, and we can guide them to adopt positive coping styles.

This study shows that there is a positive correlation between resilience and positive coping styles. Resilience refers to the individual's personal potential generated when the stimulus, trauma and other emergencies occur around the individual, which enables them to have the courage to overcome difficulties firmly (Babić et al. 2020; Mahmoud and Rothenberger 2019). One important factor is for individuals to cope with psychological pressure and maintain mental health (Johnson et al. 2017; Reivich et al. 2011; Tuck and Anderson 2014), as that can reduce the negative impact of stressors and is an effective psychological feature for individuals to cope with negative emotions (Liu et al. 2019). Since the amount of resilience differs between individuals, individual attitudes and coping styles are different when encountering emergencies or stimuli. Having high psychological resilience can help one to effectively resist the impact of negative events, restrict negative emotions, play a protective role, generate positive coping styles, and rebuild mental health (Sisto et al. 2019; Tay and Lim 2020). Good psychological resilience can help nurses adapt more quickly to anxiety or challenges and then more calmly take positive measures to solve the problems caused by emergencies and always stick to them. This finding provides some ideas for the management of emergency aid teams to carry out psychological intervention during major public health emergencies.

The study pointed out that greater psychological resilience can help nurses improve their sense of self-efficacy and their ability to realistically assess stress and adjust their emotional response to others. Positive self-dialogue, managing negative self-dialogue, and sharing work plans with colleagues are the keys to preventing burnout and reducing the negative impact of emotional labor (Foster et al. 2018). At the social level, local health-related departments need to actively issue policies and effective guidelines to help nurses actively respond and adjust to the crisis, to strengthen nurses' ability to protect themselves and provide services, and to improve their ability and confidence to respond to public emergencies (Balay-Odao et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2021).

There are several limitations of this study. First, the study had a relatively small number of participants, and the period of data collection was not long enough to explore the true effect. Second, the selection of respondents involved convenience sampling and was voluntary; hence, the study could suffer from selection bias, such as volunteer bias. Third, since it is a cross-sectional study, no causal explanation can be obtained between the variables. The solution to such a quandary would be achieved by conducting a number of prospective longitudinal analogous studies, the results of which would be expected to complement the cross-sectional findings of this study.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicated that social support and psychological resilience are influential factors of positive coping among medical staff, and tenacity and friend support were the main influencing factors. Positive coping of medical staff can be enhanced through support from friends, which helps them actively respond and adjust in a crisis and increases their ability to protect themselves and provide services.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable

References

Alghamdi MG (2016) Nursing workload: a concept analysis. J Nurs Manag 24(4):449–457. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12354

Babić R et al (2020) Resilience in health and illness. Psychiatr Danub 32(Suppl 2):226–232

Balay-Odao EM et al (2020) Hospital preparedness, resilience, and psychological burden among clinical nurses in addressing the COVID-19 crisis in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Front Public Health 8:573932. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.573932

Cooper AL et al (2021) Nurse resilience for clinical practice: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs 77(6):2623–2640. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14763

Dunstan DA, Scott N (2020) Norms for Zung's Self-rating Anxiety Scale. BMC Psychiat 20(1):90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2427-6

Feng L, Yin R (2021) Social support and hope mediate the relationship between gratitude and depression among front-line medical staff during the pandemic of COVID-19. Front Psychol 12:623873. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.623873

Fenollar F et al (2021) Evaluation of the Panbio COVID-19 rapid antigen detection test device for the screening of patients with COVID-19. J Clin Microbiol 59(2):e02589–e02620. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.02589-20

Foster K et al (2018) Strengthening mental health nurses' resilience through a workplace resilience programme: a qualitative inquiry. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 25(5-6):338–348. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12467

Herbert MS et al (2018) Race/ethnicity, psychological resilience, and social support among OEF/OIF combat veterans. Psychiatry Res 265:265–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.04.052

Johnson J et al (2017) Resilience to emotional distress in response to failure, error or mistakes: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 52:19–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.11.007

Kartal M et al (2022) The effect of emergency nurses' psychological resilience on their thanatophobic behaviors: a cross-sectional Study. Omega (Westport) 2022:302228221128156. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228221128156

Khan Y et al (2018) Public health emergency preparedness: a framework to promote resilience. BMC Public Health 18(1):1344. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6250-7

Kuiper H et al (2019) Measuring resilience with the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): which version to choose? Spinal Cord 57(5):360–366. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-019-0240-1

Labrague LJ (2021) Psychological resilience, coping behaviours and social support among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Nurs Manag 29(7):1893–1905. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13336

Lai J et al (2020) Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 3(3):e203976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

Lian A et al (2021) Investigation on psychological state of occupational exposure of medical staff in operation room under novel coronavirus. Saudi J Biol Sci 28(5):2726–2732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.02.080

Liu WJ et al (2019) Mediating role of resilience in relationship between negative life events and depression among Chinese adolescents. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 33(6):116–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2019.10.004

Liu J et al (2022) Vaccines elicit highly conserved cellular immunity to SARS-CoV-2 Omicron. Nature 603(7901):493–496. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04465-y

Mahmoud NN, Rothenberger D (2019) From burnout to well-being: a focus on resilience. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 32(6):415–423. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1692710

Pushkarev GS et al (2020) The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS): reliability and validity of Russian version. Clin Gerontol 43(3):331–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2018.1558325

Reivich KJ et al (2011) Master resilience training in the U.S. Army. Am Psychol 66(1):25–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021897

Saedpanah D et al (2016) The effect of emotion regulation training on occupational stress of critical care nurses. J Clin Diagn Res 10(12):Vc01–vc04. https://doi.org/10.7860/jcdr/2016/23693.9042

Saxena SK et al (2022) Characterization of the novel SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant of concern and its global perspective. J Med Virol 94(4):1738–1744. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27524

Shanafelt T et al (2020) Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 323(21):2133–2134. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5893

Shigemura J et al (2020) Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 74(4):281–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12988

Sisto A et al (2019) Towards a transversal definition of psychological resilience: a literature review. Medicina (Kaunas) 55(11):745. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55110745

Sun N et al (2020) A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am J Infect Control 48(6):592–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.03.018

Sun R et al (2022) Identifying the risk features for occupational stress in medical workers: a cross-sectional study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 95(2):451–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01762-3

Tay PKC, Lim KK (2020)Psychological resilience as an emergent characteristic for well-being: a pragmatic view. Gerontology 66(5):476–483. https://doi.org/10.1159/000509210

Tuck I, Anderson L (2014) Forgiveness, flourishing, and resilience: the influences of expressions of spirituality on mental health recovery. Issues Ment Health Nurs 35(4):277–282. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2014.885623

Wang D et al (2020) Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama 323(11):1061–1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.1585

Wang H et al (2021) Emotional exhaustion in front-line healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, China: the effects of time pressure, social sharing and cognitive appraisal. BMC Public Health 21(1):829. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10891-w

Xie J et al (2021) Psychological health issues of medical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychiat 12:611223. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.611223

Zhang XB et al (2021) Prevalence and influencing factors of anxiety and depression symptoms among the first-line medical staff in Wuhan mobile cabin hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic: a cross-sectional survey. Medicine (Baltimore) 100(21):e25945. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000025945

Zhou P et al (2020) A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 579(7798):270–273. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7

Zung WW (1971) A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 12(6):371–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0033-3182(71)71479-0

Acknowledgements

We want to thank our individual or guardian participants for consenting to the publication of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tao-Hsin Tung and Fengmin Cheng (corresponding authors) — conceptualization of study design, coordination of communication effort, project, data analysis.

Dandan Han (first author) — manuscript submission, data collection, data analysis, drafted and edited manuscript.

Yupei Yang, Wei Zhang (second and third author) — data collection, data analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This article approved by the ethics committee of Taizhou Hospital of Zhejiang Province affiliated to Wenzhou Medical University.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from individual or guardian participants.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual or guardian participants for publication of this paper

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, D., Yang, Y., Zhang, W. et al. The relationship between social support, psychological resilience, and positive coping among medical staff during emergency assistance for public health emergency. J Public Health (Berl.) (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-02113-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-02113-x