Abstract

Aim

Antimicrobial resistance is a global health crisis which undermines the effectiveness of current modern therapeutics against microbial infections and demands effective governance at all levels to effectively address the challenge. The aim of the study was to analyse Australia’s National Action Plan on antimicrobial resistance using a governance framework to facilitate discussion on the state of implementation.

Methods

A governance framework was used to facilitate the systematic analysis of Australia’s National Action Plan on antimicrobial resistance through iterative coding of activities listed within the working documents.

Results

From the analysis, 1435 codes were created in congruence with the governance framework. The Australian National Action Plan was aligned with the Global Action Plan on antimicrobial resistance in scope of objectives. The most frequent code was research and innovation (n = 180, 12.5%). The least frequent theme discussed was equity. No strategic vision or objectives were outlined within any of the documents to measure implementation progress.

Conclusions

Overall, Australia’s governance on AMR has demonstrated siloed implementation with an absence of strategic objectives to measure progress. Governance structure, surveillance and mechanisms for stakeholder participation have been identified as potential actionable points for AMR strategy refinement that can improve overall accountability towards progress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance and governance

The World Health Organization (WHO) has acknowledged that antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a global threat to human health and the viability of current therapeutics (Padiyara et al. 2018; Ruckert et al. 2020; IACG 2018b). Multi-drug resistant and pan-drug resistant organisms are complex public health challenges that threaten our ability to treat simple microbial infections (Basak et al. 2016). The emergence of these organisms has been observed across human and animal health, and in the environment (White and Hughes 2019). Historical reliance on the development of novel antibiotic classes to address antibiotic resistance (AbR) no longer offers a sustainable solution given the development of resistance outpaces the development of new antimicrobial classes (Ruckert et al. 2020; Butler and Paterson 2020). In acknowledgement of the highly interconnected nature of AMR across domains, a tripartite partnership of global leadership was formed with leadership from the WHO, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and the Office International des Epizooties (OIE) (World Animal Health Organization) (WHO 2015). The concerted efforts have resulted in the formation of the Global Action Plan (GAP) for AMR (WHO 2015).

The objectives of the GAP foreground the prioritisation of AMR as a public health issue by calling for engagement of stakeholders, inclusivity of sectors, accountability and capacity building as responses towards AMR (WHO 2015). At the national level, the objectives of the GAP are translated into a National Action Plan (NAP) to better reflect country-specific nuances regarding AMR (IACG 2018a). Australia produced its first AMR strategy in 2015 with supporting implementation plans to both meet global objectives as outlined by the GAP and adjust for contextual factors (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture 2015). The Australian NAP stipulates activities in accordance to overarching objectives at a national level for national and subnational actors to achieve (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture 2015). In efforts to ensure viability of governance and efficacy of implemented activities, there is a need for on-going monitoring and evaluation to identify potential barriers and actionable lever points (Moran 2019). The success of the implementation plans is imperative to the realisation of AMR mitigation endeavours (IACG 2018a). However, governance is increasingly complex and realistic engagement remains problematic (IACG 2018a; Hannah and Baekkeskov 2020).

Challenges of antimicrobial resistance

The One Health approach to AMR governance, the recognition of the embedded interconnectedness of human, animal and environmental health sectors (Kahn 2017), presents a fundamental dilemma of conflicting interests at a national level that is compounded by the complexity of maintaining inclusivity of multiple sectors. The polysemous interpretation of the GAP and an absence of comprehensive policy assessment have resulted in inherent discrepancies within the policy and decision-making space (Hannah and Baekkeskov 2020; Naylor et al. 2021). The challenge of congruence amongst decision-makers is further compounded by documented difficulties of coordinating objectives, absence of defined structures, inconsistent political willingness, and inadequate capacity to carry out initiatives (Ruckert et al. 2020). As a resolute approach to address the challenges, systematically analysing current national actions and facilitating subsequent discussion as to identify the strengths, weaknesses and opportunities can lead to the generation of impactful and feasible interventions.

Antimicrobial resistance governance framework

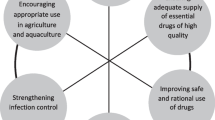

A framework that sought to classify the interrelated dynamics in the One Health approach to AMR was outlined by Anderson et al. (Anderson et al. 2019). The framework stipulates three main domains for AMR governance in policy design, implementation tools, and mentoring and evaluation as key areas (Anderson et al. 2019). Further work by Chua et al. (2021) advanced the existing framework by consolidating themes with their complementary ideological foundations. The following iteration upheld the essential definitions as previously defined for each component (Chua et al. 2021). Overall, the intention of this framework has been to promote structured discussion in the different domains of governance. A secondary function of the framework can be derived as analysing activities facilitates internal dialogue as to representation and contributors within the NAP. Figure 1 shows the adaptations made by Chua et al. (2021).

Adapted antimicrobial resistance governance framework for evaluating National Action Plans. Chua et al. (2021)

A potential case study for facilitated discussion surrounding AMR governance is Australia. Australia’s governance of AMR has experience progression as evidenced by the publication of a second NAP that further expands the previous released plan (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture 2015). From the date of publication, Australia has published detailed progress reports (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2021a; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2017) in the activities undertaken and has detailed a new plan for 2020 and beyond (Department of Health and Department of Argriculture Water and Environment 2020). Given the comprehensive progress reports completed for Australia’s AMR strategy, an opportunity is provided for insightful commentary to be made over the direction of Australia’s AMR governance.

Rationale and aims

Through an analytical framework approach, governance can be objectively discussed based on activities completed. Discussion may be framed surrounding AMR governance to identify encompassing themes and identify the direction of governance. The aim of this study is to: (i) Apply the governance framework detailed by Anderson et al. (Anderson et al. 2019) to Australia’s NAPs and evaluate progress and activities. The objectives are to (i) provide structured discussion on the progress and direction of Australia’s AMR governance based on the activities identified and (ii) identify potential opportunities to improve the activities in the Australian NAP.

Methodology and methods

Analysis of Australia’s National Action Plan implementation

At the time of publication, Australia’s published reports have indicated there are two distinct timeframes, 2015 to 2019 and 2020 and beyond. As a result, coded activities were first categorised as past/current (activities completed or still ongoing), or future/planning (proposed activities) documents based on timelines specified within the documents. To identify past activities undertaken to meet objectives as outlined by the framework, content from the 2015–2019 NAP on AMR was analysed. For current and future planned activities, the 2020 and beyond NAP was analysed. In cases where an activity or priority area was mentioned within two or more documents, the one with the most detail was included to be displayed in the summary results. The documents searched and used for content analysis are found within Table 1.

A comprehensive text-based analysis of governance documents was completed to evaluate the implementation of Australia’s NAP by PD. A two-stage approach was employed in the analysis of the relevant governance documents. The first stage looked focused on assessing the compatibility of the objectives of the NAP with the GAP. The second stage employed an iterative detailed content analysis of the working documents using the domains definitions outlined within Anderson et al. (2019). The level of analysis focused on thematic alignment of the contents of the governance documents with the Anderson et al. (2019) domain definitions. If there was ideological similarity, the text was coded according to the domain in which it satisfies. The frequency of codes was recorded to identify prominence of themes throughout the documents. This process was undertaken with the understanding the inclusion of frequency provides an indication of commonality but has insignificant explanatory power with regard to the relative importance of each domain. A diagram illustrating the content analysis procedure can be seen in Fig. 2.

Data collection and storage

Content was analysed and iteratively coded using NVivo (Version 12, QSR International) by identifying congruencies between the item described and the definition outlined within Anderson et al.’s (2019) governance framework. Nodes were created in alignment with headings detailed by Chua et al. (2021). Documents were then reviewed and coded through an iterative procedure whereby coding was conducted theme by theme.

Results

Results of document analysis using the governance framework

Overall, a total of 1435 codes were produced following the analysis of relevant AMR governance documents. The final progress report on Australia’s first national antimicrobial resistance strategy represented the largest proportion of items coded (n = 515, 35.9%). This was followed by Australia’s First national antimicrobial resistance strategy 2015–2019 progress report (n = 286, 19.9%). The least coded document was Australia’s national antimicrobial resistance strategy 2020 and beyond (n = 33, 2.3%). Figure 3 presents the results of coding for all documents. Stratifying by theme, the most prominent category throughout the working documents was research and innovation (n = 180, 12.5%) followed by surveillance (n = 165, 11.5%). The least present theme was equity (n = 14, 0.9%) followed by future expansion and implementation (n = 24, 1.67%). The frequency of all codes is presented in Fig. 4.

The frequency distribution of themes across the Australian national plan documents using the framework definitions provided by Anderson et al. (2019)

Alignment of Global Action Plan and Australia’s National Action Plan on antimicrobial resistance strategic objectives

The content analysis of priorities and strategic objectives within Australia’s NAP is seen to be congruent with the GAP strategic objectives as summarised in Table 2. Whilst the GAP expresses five strategic objectives to mitigate AMR, Australia has seven. There were no absent domains not covered by the NAP. An additional priority included in Australia’s NAP was the strengthening of global collaboration and regional partnerships in AMR efforts.

Alignment with antimicrobial resistance governance framework

Key activities within Australia’s National Action Plan on AMR were aligned with Anderson et al. (2019) framework definitions. As a general trend, activities were continued with additions from the prior activities to future priorities. There was often repetition of activities throughout various working documents. Table 3 presents the main findings from the analysis using the governance framework. Full contents from the document analysis using the governance framework have been provided in supplementary file 1.

Policy design

Overall, 323 codes (22.5%) for items within the Australian NAP documents were categorised to policy and design. There was a change in goals that were reflective of achievements made from previous activities. All the individual elements of strategic vision, accountability and coordination, participation, transparency, and equity were detailed throughout the working documents in some capacity.

Strategic vision

No numerical goal was stipulated throughout any iteration of the working documents. Strategic goals have been qualitatively described and allocation of responsibility has been delegated to relevant stakeholders. The changes noted between the two documents have been detailed to reflect the growing scope of AMR with the future priority highlighting the need to encompass more classes of antimicrobials as an area of concern (Department of Health and Department of Argriculture Water and Environment 2020).

Accountability and coordination

Accountability and coordination of relevant stakeholders in AMR mitigation efforts is clearly defined by the plans. The implementation plan of 2015–2019 (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2016) and NAP of 2020 and beyond (Department of Health and Department of Argriculture Water and Environment 2020) detail the actors that are responsible for their respective priority area. The multi-sectorial input is managed by representatives in the AMRPC Steering group with technical support given by ASTAG (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2016).

Participation

Participation in the overall strategies have been multi-sectorial. The plans detail the engagement of animal and human health domains. Evidence of collaboration appears in AAW which endeavours to increase the public profile of AMR and relevance to society (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2016). Furthermore, participation is still growing as reflected by the development of greater animal health stewardship groups within the food industry.

Transparency

Transparency for AMR objectives and guidelines has been highlighted to be a priority. In both AMR strategies there is an emphasis on creating and maintaining the integrity of readily available resources for all relevant clinical and non-clinical stakeholders. Data and objectives used to inform decisions are also publicly available through the establishment of the One Health AMR website.

Equity

Equity in the plans is acknowledged to encompass the capacity for which the public can receive quality therapeutics. The priorities reflected within the 2015–2019 NAP highlight the need to improve incentives to vaccinations provision and the review of antibiotic supplies in the community (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2017). The subsequent 2020 and beyond plan consolidates the priorities by aiming to boost regulatory capacity to ensure the supply of quality antimicrobials for usage within the community (Department of Health and Department of Argriculture Water and Environment 2020).

Implementation tools

Implementation tools were the most frequent category of codes assigned to items within the NAP documents (n = 789, 54.98%). Implementation tools are the means in which the AMR objectives are to be achieved. This includes surveillance, optimisation of antimicrobial usage, infection prevention and control, education, research and innovation, and international collaboration. Past and future priorities within the NAP highlight a commitment to building and maintaining capacity to address AMR through surveillance, education and research (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2016, Department of Health and Department of Argriculture Water and Environment 2020).

Surveillance

Surveillance aims at gathering and evaluating the current evidence of antimicrobial usage and AMR within Australia. Past activities have established AURA surveillance to monitor AMR in human health (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2016). The surveillance system is supported by established data repositories with AGAR and NAUSP/NAPS. Furthermore, there is opportunity for the expansion of AMR surveillance capacity in non-human domains with the formation of animal health surveillance in food animals. Future priorities have expressed desire for expansion into non-human health domains and further refine surveillance methodology and its continued use as a monitoring and evaluative tool.

Optimising antimicrobial usage and infection prevention and control

The recognition of poor hygiene, sanitation and inappropriate antimicrobial usage, as drivers of AMR has been similarly expressed through the stewardship priorities detailed within both plans. Past priorities have been centred around assuring compliance with national health service standards and adequate dissemination of relevant guidelines. Future priorities in both reflect a growing need to increase regulatory power in both antimicrobial usage and biosecurity management standards.

Education

Education has been emphasised in both documents to be centred around support for animal and human health practitioners. This includes support in reinforcing messages with patients and clients, increasing knowledge of national standards and policies, and the modifying educational curriculum competencies to emphasise AMR. Initiatives within this area include analysis of general practitioner prescribing patterns and training activities and forums for research and clinical perspectives.

Research and innovation and international collaboration

The emphasis of research and innovation in the context of AMR has been identified as a priority throughout the documents as evidenced by the minimal variation in priorities over time. Initial priorities and objectives were centred around obtaining funding for research in the development of diagnostic tools and novel therapeutics, improvement of surveillance, and evaluation of stewardship programs. Subsequent priorities have reflected the notion for research in the need for coordination of research and development activities, flexible national AMR research and development agenda, and sustainability of funding. International collaboration builds upon the national research generated. The priorities included within this domain are to disseminate and contribute to overall AMR understanding within the Southeast Asia and Pacific regions. Other areas encompassed by international collaboration include the continued assurance for national surveillance data to be used by global surveillance programs.

Monitoring and evaluation

Categorisation of monitoring evaluation codes were less common (n = 248, 17.2%). Monitoring and evaluation focused on mechanisms to gather evidence from implementation processes and inform decision-making procedures. AURA surveillance was commonly referred to as the mechanism to relay feedback back to constituents.

Effectiveness, reporting andfeedback mechanisms

Effectiveness and feedback mechanisms are important to inform the decision-making processes within AMR strategies. The 2015–2019 NAP focused on establishing mechanisms for feedback which allowed for service evaluation and monitoring of trends in AMU and AMR. The main source of data is that of the AURA surveillance system. Future priorities are centred around the consolidation of such practices into relevant frameworks and review of current evidence.

Sustainability

Sustainability represented the least frequent category of codes assigned to items (n = 75, 5.22%). The domain for sustainability describes mechanisms to maintain current stewardship efforts. The domains measured by sustainability are funding and resource allocation and expansion plans.

Funding, resource allocation and expansion plans

The allocation of funds and resources has been briefly mentioned through the initial NAP (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture 2015). Initial funding for AMR activities and objectives were funded by research call and grants. There was emphasis for greater financial sustainability as mentioned by the 2020 and beyond NAP (Department of Health and Department of Argriculture Water and Environment 2020). Expansion plans have focused on understanding the determinants of AMR in the environmental, plant and food sectors and integrating animal and human health surveillance systems.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the past and future priorities of Australia’s NAP on AMR using a governance framework provided by Anderson et al. (Anderson et al. 2019). The framework has provided a structural guide to assess NAP contents and facilitate the identification of opportunities and general trends in governance. The analysis has highlighted research and innovation as a top priority within the AMR strategy. As the most mentioned theme, the prominence of research and innovation as a theme suggests there has been a concerted focus on understanding AMR. The implication of the theme’s prominence indicates progress may be constrained by the absence of a consolidated evidence base for strategic objectives to be constructed from. The use of progress reports has also been demonstrated to be effective in facilitating discussion to ascertain the current state and direction of governance and identify potential levers for improvement.

The absence of strategic vision and objectives

As an overall trend, there is evidence to argue that general political apathy has been exercised towards AMR within Australia resulting in the absence of strategic objectives. Although the priorities outlined within the NAP (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture 2015) are congruent with the objectives of the GAP (WHO 2015), there is considerable questionability in Australia’s progress. The absence of strategic vision and objectives prohibits any insightful commentary to be made towards stewardship and initiative efficacy. The activities listed within the working documents superficially cover a considerable breath but lack any sector-specific accountability through the delegation of objectives. The superficiality is evidenced by the dichotomous nature of activities such as creating proof-of-concept models and program implementation (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2016) without associated feedback mechanisms to evaluate effectiveness. Ideally with political willingness and depth, AMR stewardship mimics Hannah and Baekkeskov’s (2020) observation of the United Kingdom’s NAP where the authors detail clear dissemination and delegation of measurable, sector-specific goals. The absence of strategic vision limits insight regarding the current direction of AMR governance within Australia and requires urgent attention.

A noteworthy point of discussion from the analysis is Australia’s organic approach to AMR governance and surveillance. Within the elements of policy design, there is an absence of legally binding agreements between stakeholders. Instead, the mechanisms identified suggest a greater emphasis on voluntary participation and partnerships between groups as evidenced by the formation of AMRPC and ASTAG (Department of Agriculture and Water Resources 2019; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture 2015; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2017; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2021a; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2016; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2021b; Department of Health and Department of Argriculture Water and Environment 2020). The contrast to the voluntary nature is active governance outlined by the goal-orientated and legislation supported approach found within Europe (Birgand et al. 2018). To demonstrate, a commonality between the German (Birgand et al. 2018) and Australian NAP (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture 2015) is the creation of AMR surveillance systems. Within the Australian context, AURA has been established through voluntary contributions by participating hospitals (ACSQHC 2021). In Germany, legal power provided by the Protection Against Infection Act (IfSG) necessitates mandatory surveillance by all hospitals (Birgand et al. 2018). The difference in governance draws discussion surrounding the efficacy of the respective approaches. As an interesting point of contention, the macroscopic structure of governance and outcomes of NAPs have yet to be thoroughly examined throughout literature. A potential implication of this finding may necessitate further discourse surrounding the benefits and feasibility of constructing legislation as a foundation for AMR stewardship within Australia.

The need for mechanisms in coordinating and holding accountability in Australia’s antimicrobial resistance strategy

Accountability and coordination have been emphasised as foundational elements of Australia’s AMR strategy by the frequency of mentions within the NAP documents. However, further examination of activities documented in the working documents using the governance framework reveal the macroscopic focus of programs are generally self-contained (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture 2015; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2017; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2021a; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2016; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2021b; Department of Health and Department of Argriculture Water and Environment 2020). Fundamentally, this suggests policy and AMR stewardship activity implementation have been done in a siloed manner. The implications of the isolated approach detracts from expressed objectives of the GAP for a One Health approach (WHO 2015) and contradict expressed interests for concerted action encompassing multiple sectors within the working documents (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture 2015; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2021b). A pragmatic explanation for the contradiction is the absence of an interfacing mechanism between stakeholders. Currently, there is no overarching governing body or working group with the capability to contend with the varying interests of stakeholders and set common objectives. This finding reinforces the need to develop cross-sector communication mechanisms for facilitating connections between stakeholders.

An intriguing observation derived from the analysis of NAP documents posits that the paucity of sectoral interfaces could be attributed to the adoption of a non-binding governance approach. An illustrative example is the isolation AMR and AMU data necessary to develop a One Health surveillance system. AMR and AMU data from the animal health sector is a necessary component to achieve the NAP objective for One Health surveillance (Department of Health 2019; Department of Agriculture and Water Resources 2019; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture 2015; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2017; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2021a; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2016; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2021b; Department of Health and Department of Argriculture Water and Environment 2020). As it remains, integration of data sources has not been attempted and no tangible One Health system has been conceptualised. Wider literature provides explanations of financial incentives associated with agricultural antibiotic use (Mitchell et al. 2020) or ambivalence to the subject matter (Golding et al. 2019) as barriers to data sharing. From a governance perspective, the development of an organisation with legislative endorsement to rigidly define and disseminate common goals across the different sectors may act as impetus to overcome the barriers. In a theoretical capacity, this organisation should be capable of deliberating through sector-specific interests, delegating accountability to stakeholders, and act as a facilitator towards One Health surveillance. Through this example, the benefit of binding governance should be explored as an avenue to improve progress in the overall AMR mitigation strategy.

Antimicrobial resistance surveillance: the key for strategic vision

The enhancement of AMR surveillance is crucial to facilitating improved political engagement by delineating strategic objectives. Surveillance of AMR has been emphasised within the working documents as a fundamental element of governance. Through its function, public health surveillance systems provide data to identify trends and monitor progress to generate action and inform refinement procedures (Wolicki et al. 2016). Improving AURA will strengthen AMR enumeration endeavours and provide a foundation for action to be generated. However, the materialisation of goals has yet to be demonstrated in any capacity suggesting the absence of improvement processes. Indeed, the enumeration of AMR as impetus for action has been acknowledged by AURA annual reports (ACSQHC 2021; ACSQHC 2016). Explanations offered by AURA reports suggest the naivety in surveillance structure and the construction of goals being contingent on further improvement of the system (ACSQHC 2021; ACSQHC 2016). By strengthening surveillance efforts through addressing the concerns, the potential benefit will facilitate the generation of strategic vision and potentially allow for lesser discussed themes such as equity to be targeted. This promotion of strengthened surveillance has a cascading effect whereby it may potentially incite heightened political willingness with progress being measurable.

Potential opportunities for implementation in the National Action Plan

Under-representation of sectors presents a difficult challenge to implementing a holistic AMR strategy. There exists a disconnect between the desired interconnectedness between health sectors and discernible outputs from implementation of the NAP. The results of the analysis indicate there is an absence of activities which demonstrate any significant level of integration beyond speculative conceptualisation. For example, amongst NAP governance documents there exists a unanimous sentiment to emphasise a One Health approach in surveillance (Department of Agriculture and Water Resources 2019; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture 2015; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2017; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2021a; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2016; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2021b; Department of Health and Department of Argriculture Water and Environment 2020). The private healthcare sector and animal health AMR data remains to be integrated despite being crucial elements to monitoring AMR through a One Health paradigm (Department of Health and Department of Agriculture 2015; Department of Health and Department of Argriculture Water and Environment 2020; Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment 2021a; ACSQHC 2021). The difficulty in engaging stakeholders in consolidation efforts of data, and the sectors in general, may be a consequence of the current governance structure possessing inadequate legislative remit to facilitate integration. A solution to enable remit over these sectors requires strategic objectives to be established. With strategic objectives established, auxiliary systems and processes can be implemented to achieve the desired interconnectedness through procedures that are structured in a manner that deliberates stakeholder accountability. Indeed, the solution is simplistic but, requires political willingness to commit and the refinement of current monitoring and evaluation systems to enumerate goals.

Strengths and limitations

The research completed has its own strengths and weaknesses. A strength of the research is the use of Anderson et al.’s (2019) framework to analyse Australia’s NAP on AMR. The framework has two innate benefits. The first is it allows for elements within the working documents to be systematically analysed against definitions. Secondly, the framework was specifically developed for AMR governance, so the usage of the framework facilitates a holistic view of the status of AMR governance.

The limitations of the study lie within the text-based analysis. The coding of activities is dependent on the interpretation of the researcher which has the potential to produce bias. However, the use of the framework allows for a foundation for activities to be coded and as such limit the bias. Another limitation of the work completed is the exclusion of academic literature. As the work was primarily focused on the analysis of governance documents, it is possible for other academic literature surrounding Australia’s AMR governance to be excluded. Despite the limitations, this study serves to facilitate discussion surrounding Australia’s AMR strategy.

Conclusions and further work

The Australian NAP on AMR has been found to be in alignment with the GAP through the analysis using Anderson et al.’s (2019) framework. The discussion facilitated by the framework has identified the misalignment of the desired, idealistic One Health approach with what is presently actioned. Noteworthy findings from the study suggest there is an inherent need for strategic indicators and objectives to be materialised to truly measure progress in AMR mitigation efforts. Whilst the conceptualisation of strategic vision is necessary, in the current state it is an idealistic hypothetical. There exists further complexity in the need for the development of mechanisms which aim to overall coordinate stakeholders and facilitate deliberation, refinement of AURA surveillance and agreeance on the responsibilities of One Health. Furthermore, there are inherent opportunities to explore overall governance and understand if current political structures are adequate for delegating accountability and improving coordination amongst relevant stakeholders.

The study’s findings can be translated into actionable recommendations to strengthen Australia’s AMR governance. The recommendations are to:

-

Develop strategic objectives and goals that are a necessity for evaluating and monitoring the current direction and effectiveness of current and future actions.

-

Further refine and develop Australia’s AMR surveillance system needs to materialise objectives under the premise of One Health.

-

Develop cross-sector interfacing mechanisms for which stakeholders deliberate on responsibilities and accountability.

-

Examine the political and governance structures that enable capacity for initiatives and action.

Data availability

All data is provided in the supplementary files.

Code availability

Not applicable. The software required to view results is NVivo (Version 12, QSR International).

References

ACSQHC (2016) AURA 2016: First Australian report on antimicrobial use and resistance in human health - full report, Australian commission on safety and quality in health care. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/AURA-2016-First-Australian-Report-on-Antimicrobial-use-and-resistance-in-human-health.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2021

ACSQHC (2021) AURA 2021: Fourth Australian report on antimicrobial use and resistance in human health, australian commission on safety and quality in health care. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-09/aura_2021_-_report_-_final_accessible_pdf_-_for_web_publication.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2021

Anderson M, Schulze K, Cassini A, Plachouras D, Mossialos E (2019) A governance framework for development and assessment of national action plans on antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect Dis 19(11):e371–e384

Basak S, Singh P, Rajurkar M (2016) Multidrug Resistant and Extensively Drug Resistant Bacteria: a Study. J Pathog 2016:4065603

Birgand G, Castro-Sanchez E, Hansen S, Gastmeier P, Lucet JC, Ferlie E, Holmes A, Ahmad R (2018) Comparison of governance approaches for the control of antimicrobial resistance: analysis of three European countries. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 7(1):28

Butler MS, Paterson DL (2020) Antibiotics in the clinical pipeline in October 2019. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 73:329–364

Chua AQ, Verma M, Hsu LY, Legido-Quigley H (2021) An analysis of national action plans on antimicrobial resistance in Southeast Asia using a governance framework approach. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 7:100084

Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (2019) Responding to antimicrobial resistance: australian animal sector national antimicrobial resistance plan 2018, Australian Government. https://www.awe.gov.au/sites/default/files/sitecollectiondocuments/animal/health/aus-animal-sectornational-amr-plan-2018.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2022

Department of health and department of agriculture (2015) Australia's first national antimicrobial resistance strategy 2015-2019, Australian Government. https://www.amr.gov.au/resources/national-amr-strategy. Accessed 30 Oct 2021

Department of health and department of agriculture water and the environment (2017) Australia’s first national antimicrobial resistance strategy 2015–2019 Progress Report, Australian Government. https://www.amr.gov.au/file/761/download?token=pW2frTWR. Accessed 15 Sep 2022

Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment (2021a) Final Progress Report: Australia’s First National Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy 2015–2019, Australian Government. https://www.amr.gov.au/file/1411/download?token=ikXgOPVe. Accessed 12 Jan 2022

Department of Health and Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment (2021b) One Health Master Action Plan for Australia's National Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy – 2020 and beyond, Australian Government. https://www.amr.gov.au/file/1407/download?token=rGYapZkl. Accessed 12 Jan 2022

Department of Health and Department of Agriculture (2015) Australia's First National Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy 2015 - 2019, Australian Government. https://www.amr.gov.au/resources/national-amr-strategy. Accessed 15 Sep 2021

Department of health and department of agriculture water and environment (2020) Australia’s national antimicrobial resistance strategy – 2020 and beyond. https://www.amr.gov.au/file/1398/download?token=NLvVTd_j. Accessed 12 Jan 2022

Department of Health (2019) 2018–19 Report on the Operation of the Aged Care Act 1997, Department of Health. https://gen-agedcaredata.gov.au/www_aihwgen/media/ROACA/2018-19-ROACA.pdf. Accessed 12 Sep 2021

Golding SE, Ogden J, Higgins HM (2019) Shared goals, different barriers: a qualitative study of UK veterinarians’ and farmers’ beliefs about antimicrobial resistance and stewardship. Front Vet Sci 6(APR):132

Hannah A, Baekkeskov E (2020) The promises and pitfalls of polysemic ideas: ‘One Health’ and antimicrobial resistance policy in Australia and the UK. Policy Sci 53(3):437–452

IACG (2018a) Antimicrobial resistance: national action plans, 2015, Interagency Coordination Group. https://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/publications/global-action-plan/en/. Accessed 15 Sep 2021

IACG (2018b) Future global governance for antimicrobial resistance IACG discussion paper. Interagency Coordination Group. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/antimicrobial-resistance/amr-gcp-tjs/iacg-future-global-governance-for-amr-120718.pdf

Kahn LH (2017) Antimicrobial resistance: a One Health perspective. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 111(6):255–260

Mitchell MEV, Alders R, Unger F, Nguyen-Viet H, Le TTH, Toribio JA (2020) The challenges of investigating antimicrobial resistance in Vietnam - what benefits does a One Health approach offer the animal and human health sectors? BMC Public Health 20(1):213

Moran D (2019) A framework for improved one health governance and policy making for antimicrobial use. BMJ Glob Health 4(5):e001807

Naylor NR, Lines J, Waage J, Wieland B, Knight GM (2021) Quantitatively evaluating the cross-sectoral and One Health impact of interventions: a scoping review and case study of antimicrobial resistance. One Health 11:100194

Padiyara P, Inoue H, Sprenger M (2018) Global governance mechanisms to address antimicrobial resistance. Infect Dis (auckl) 11:1178633718767887

Ruckert A, Fafard P, Hindmarch S, Morris A, Packer C, Patrick D, Weese S, Wilson K, Wong A, Labonte R (2020) Governing antimicrobial resistance: a narrative review of global governance mechanisms. J Public Health Policy 41(4):515–528

White A, Hughes JM (2019) Critical importance of a one health approach to antimicrobial resistance’. EcoHealth 16(3):404–409

WHO (2015) Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. World Health Organization. https://ahpsr.who.int/publications/i/item/global-action-plan-on-antimicrobial-resistance. Accessed 31 Jul 2021

Wolicki SB, Nuzzo JB, Blazes DL, Pitts DL, Iskander JK, Tappero JW (2016) Public health surveillance: at the core of the global health security agenda. Health Secur 14(3):185–188

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions Phu Cong Do is a recipient of the Research Training Program (RTP) scholarship for higher degree research provided by The University of Queensland. The funders have no input in the conceptualisation, data analysis, or drafting of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

• Phu Cong Do – Writing of main manuscript, editing, analysis, conceptualisation of concept and approval for publication.

• Yibeltal Assefa Alemu – Editing of manuscript, conceptualisation, approval for publication.

• Simon Andrew Reid – Editing of manuscript and approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable. The study conducted was an analysis of publicly available secondary data from reports. No human or animal subjects were involved in the study.

Consent for publication

All authors consent for the following works with figures and data to be published.

Consent to participate

No human subjects were involved in the research study conducted.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Do, P.C., Alemu, Y.A. & Reid, S.A. An analysis of Australia’s national action plan on antimicrobial resistance using a governance framework. J Public Health (Berl.) (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-02029-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-02029-6