Abstract

Introduction

Quality of work life and perception affects the productivity of healthcare professionals. The study aimed to determine the quality of work life (QWL) and job satisfaction (JS) of military healthcare professionals in Nigeria.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted at three military hospitals, one each for the Army, Navy, and Air Force. The 35-item QWL and five-item JS Index questionnaires were used to record responses from consenting professionals between January–March 2022. Appropriate descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were conducted, with p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

The overall average QWL score for the population was 86.88 ± 23.04, while overall JS had a mean score of 23.2 ± 7.102. Years of experience (β = –0.292, p = 0.018), and previous posting to war areas (β = –0.285, p = 0.022) were significant predictors of QWL, just as years of experience (β=–0281, p = 0.024) and age (β = 0.235, p = 0.097) were for JS.

Conclusion

Healthcare professionals serving in the Nigerian Armed Forces have a fair perception of their QWL and JS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the health workforce in Africa is overburdened with a density of 14.1 in a 10,000 population, making it the 2nd largest continent with a deficit of health workers (WHO 2007). It was also reported in 2019 that the Nigerian health system is such that one physician serves 5000 people in an estimated 180 million population in contrast to the one to 300 people recommended by the WHO (Adebayo and Akinyemi 2022). These unfortunate records have not overridden the requirement for health workers to achieve Universal Health Coverage and fulfil health and wellbeing for all. It is of little wonder then that Cometto and Campbell (2016) reiterated the need for an ensured investment in the health sector. These investments, ranging from quality education, working conditions, and remuneration for labour, should consequently improve the work life of health workers and create the feeling of fulfilment in rendering their services.

The Nigerian military healthcare system was primarily instituted to cater to the health needs of the men of the armed forces and their families, although, over time, its services have evolved to include the civilian population of the nation (Adebayo and Hussain 2010). More importantly, the Nigerian military medical corps is tasked with providing medical coverage for the military during its operations/exercises both internationally and locally (Maksha et al. 2017). To date, the military has had notable representations in several medical missions across Africa (Congo, Lebanon, South Sudan, Sudan, Mali, Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast, and Liberia) and has been critical in the fights against the insurgency in different parts of the country, notably north-east, north-west, and south-east. This echoes the fact that military healthcare professionals are as essential as their non-military counterparts in serving national healthcare interests (Adebayo and Hussain 2010).

However, the Nigerian military medical corps has not been without its share of the national socio-economic crises. There were two recent strike actions by the health workers in 2014 and 2018 for reasons ranging from unpaid salaries to a call for a restructuring of the medical corps and hospitals, respectively (Obinna 2018). While the quality of work life (QWL) in solely profit-based businesses is important to increase the competitiveness of their human resources through increased job satisfaction, the effect of QWL in healthcare organizations cannot be underestimated (Akinwale and George 2020). With the average healthcare budget in Nigeria at $6 per person compared to the $10,000 per person budget in the United States (Abang 2019), the majority (over 80%) of Nigerian physicians are opting for work opportunities outside the country. The reason for this geometrically increasing brain drain in the health sector is linked to factors ranging from poor remuneration to diminished job satisfaction (Akinyemi et al. 2021; Raufu 2002).

QWL is the relationship between an employee and their work environment with the focus being the desire to improve employee wellbeing and to boost the organization’s performance: it is the link between an employee and their motivation to work (Ogbuabor and Okoronkwo 2019). While the quality of work life and job satisfaction are sometimes used interchangeably, job satisfaction refers to the overall orientation of an employee to their work (Jahanbani et al. 2018). According to Akinwale and George (2020), the climate of a work environment is an important consideration in the health industry. Awosusi (2010), having assessed the QWL of nurses in tertiary hospitals in Southwestern Nigeria, reported that only 4.2% of the nurses were very satisfied with their work. The study by Akinwale and George (2020) reported a level of dissatisfaction among the sampled health professionals. These findings raise serious concerns because arguments have supported the claim that QWL influences the job satisfaction of health workers and is consequential to the productivity and quality of healthcare service deliverables (Akinwale and George 2020; Jahanbani et al. 2018; Saygili et al. 2020).

The military healthcare service is a solely government-controlled health economy through the Ministry of Defence that is operated to serve the health needs of the armed forces while providing useful assistance to the civilian healthcare systems (Bricknell and Cain 2020). It is important to identify the factors that influence the quality of the work environment/conditions and the satiety desirable from the job. With the risk and challenges of working in the health sector, the additional military status can be a challenge to a professional.

This study aimed to determine the QWL and job satisfaction of military healthcare professionals in Nigeria and the relationship between QWL and job satisfaction. The findings of this study would inform and educate all stakeholders of the health system inclusive of the government, administrators, medical professionals, trade unions, and researchers on the QWL of the military medical corps.

Methods

Design

This study adopted a cross-sectional questionnaire-based design.

Study settings, study population and sampling technique

The study was conducted among healthcare professionals who are serving in the Nigerian Armed Forces. The Nigerian Armed Forces comprise the triad of Army, Navy, and Air Force. The three arms have medical corps that serve in their hospitals which are either specialized referral centres in the cities or mobile facilities that attend to troops in military operations. Healthcare professionals that serve in the Nigerian Armed Forces include physicians, pharmacists, nurses, laboratory scientists and other support staff. An Army, a Naval and an Air Force hospital were purposively selected in the country: the criterion was that the selected hospital was the largest in terms of bed size.

Because of the job of the respondents and the restrictions to communicate with researchers, a time-based data collection was conducted between January and April 2022.

Study tool

The 35-item (eight dimensions) Quality of Work Life questionnaire by Walton and the five-item Job Satisfaction Index questionnaire adopted by House were used for this study. A section was added to document the sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents.

Study procedure

The two questionnaires were transformed into a google document and its link was shared with respondents who consented to participate in the study. Eligible respondents (military healthcare professionals in Nigeria) were approached and invited to participate in the study. The link was then sent to those that consented to participate in the study. Reminder messages were sent to the respondents after every 2 weeks until the third month with an explanation that the forms should not be completed more than once by a respondent. At the end of the pre-determined data collection period, the response submission was deactivated on the google link.

Data management and analysis

The responses were downloaded into Microsoft Excel (2019) and checked for correctness. Only the data of those who completed the sociodemographic section of the instrument in addition to the other two sections were deemed eligible for use in the data analysis. The cleaned data was exported into IBM SPSS version 25 for statistical data analysis. Frequencies and percentages were used to summarize the findings. The mean scores of the items in the QWL questionnaire were obtained as the scores of the respective dimensions. An Independent t-test (based on the test of normality) was used to compare the QWL between those who had been at the war front in the past 5 years and others. A correlation test was used to compare the association between the QWL and the job satisfaction of the respondents. The sociodemographic predictors of the respondents’ QWL and job satisfaction were determined using regression analysis. In both cases, all the variables were loaded into the regression model so that recommendations on factors to be used in improving the QWL or job satisfaction would be identified. For all analyses, p-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu State, Nigeria. The approval number is NHREC/05/01/2008B-FWA0000245 8-1RB0002323. Permission was obtained from the authorities of the selected hospitals.

Consent to participate

All respondents gave written informed consent to participate in the study. No identifier information was requested from the respondents. All information obtained from the respondents was treated with utmost confidentiality throughout the study.

Results

The total number of people that participated in the survey was 84. The demography showed that most of the respondents were within the age range of 26–34 years, 54 (64.3%), and the majority of the respondents identified as men, 60 (71.4%). Out of the 84 participants, 43 (51.2%) had single marital status, while most of the respondents, 36 (42.9%), served with the Navy division of the Nigerian military. Pharmacists represented the highest proportion 26 (31%) of health professionals that participated in the survey with nurses being the least. Overall, the majority of the health workers, 60 (71.4%), had never been posted to a battle area before (Table 1).

On the quality of work life, 12 (14.3%) and 25 (29.8%) were very dissatisfied and dissatisfied, with their remuneration (2.80 ± 0.183). Regarding the space the work occupies in the respondents’ life, 38 (45.2%) were dissatisfied with the influence of their job on their families (2.52 ± 0.114) while 33 (39.3%) were dissatisfied with the situation and frequency at which other personnel resigns from work (2.79 ± 0.102). Strikingly, 44 (52.4%) were satisfied with the pride that emanates from the social relevance and importance of being military personnel (3.26 ± 0.132). For job satisfaction, the overall mean satisfaction with the military job combined with being a health professional was 6.17 ± 0.1952, minimum–maximum of 1.0–10.0 (Tables 2 and 3).

The overall average QWL score for the population was 86.88 ± 23.04, which was at a moderate level. The findings revealed that 36 (42.9%) of the respondents in the study had a moderate level of QWL score, 15 (17.9%) had a low level and 33 (39.3%) rated high in their QWL. With dimension analysis, the QWL presented in Table 4 showed that the respondents had a mean of <2.5 in all the dimensions, with social relevance having the highest average score of 2.19 ± 0.814 (Table 4). The result in Table 5 shows that overall job satisfaction had a mean score of 23.2 ± 7.102. It also indicated that only 4 (4.8%) were highly satisfied with their jobs. In addition, 29 (34.5%) and 51 (60.7%) of the respondents were poorly and moderately satisfied with their jobs, respectively. While the military health personnel that had been to war in the past 5 years had a mean QWL of 79.96 ± 22.38, it was not significantly lower than that of their colleagues that had not gone to the battlefield in the past 5 years (89.65 ± 22.90); p = 0.082, F = 0.012. Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference in the mean job satisfaction between those that had gone to the battlefield in the past 5 years (21.88 ± 7.95) and those who had not (23.77 ± 6.73), p = 0.273, F = 0.910.

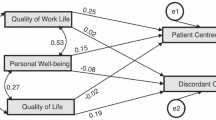

The distribution of data in Table 6 of QWL and job satisfaction from the Kolmogorov Smirnov test (KS) was normal (p = 0.067). Hence, a significant relationship exists between QWL and job satisfaction (p ≤ 0.001, r = 0.394) as indicated by the Pearson correlation coefficient results. A positive significant correlation was seen between all the components of QWL and job satisfaction (p ≤ 0.001) except in the constitutionalism component (r = 0.135). The component with the highest positive correlation was space occupation (r = 0.416), while social integration had the least (r = 0.252). The result of multivariate analysis between components of job satisfaction and QWL indicated that none of the independent variables could significantly predict job satisfaction variance. The multiple regression analysis in Table 7 shows that some components of socio-demographic data were able to predict QWL and JS. Years of experience (β = –0.292, p = 0.018) and previous posting to war areas (β = –0.285, p = 0.022) were significant predictors of QWL. Similarly, years of experience (β = –0281, p = 0.024), age (β = 0.235, p = 0.097), and previous posting to war area (β = –0.238, p = 0.055) are aspects of sociodemographic factors that can significantly predict job satisfaction.

Discussion

This research study evaluated the quality of work life and the job satisfaction of military healthcare professionals serving in the Nigerian Armed Forces. The personnel serving in the three arms of the Force, namely the Army, Navy, and Air Force were invited to participate in the study. The study sample consisted majorly of a young population, with many of them indicating that they identified with the male gender. Generally, men constitute a higher proportion of people that are recruited into the military globally. More than half of the military personnel that participated in this survey were men which is consistent with similar studies conducted among military personnel (Lopes et al. 2015; Sultan and Rashid 2015). The entry requirements for joining the military as a health professional are less stringent compared to the conditions stipulated for other individuals. In the United Kingdom, health professionals that want to serve in the military do not have to be athletically fit to join the Army reserve and have different ports of entry elucidated for them (Sultan and Rashid 2015). This is similar to the Direct Service Short Course programme that is conducted annually by the Nigerian Military to recruit persons from different walks of life.

According to the findings of this study, Nigerian military healthcare professionals have a ‘moderate’ perception of both their QWL and job satisfaction. The study found that the healthcare workers participating in the study had the highest average score in the QWL dimension’s social relevance. However, the mean score of this dimension is at a low level and is similar to other dimensions under the QWL. Previous research that was conducted among employees of Health Centers in Ahvaz Iran (Jahanbani et al. 2018) reported that the perceived QWL was generally moderate, but only low in the subscales ‘Adequate and fair compensation’, and ‘Total life space’. The ‘social relevance’ component also had the highest mean score in the study. This could mean that generally, health workers have a higher perception of social prestige which impacts the quality of work life irrespective of the aspect of service branch; civil or armed forces.

Results from another study showed that most health workers experienced low levels of QWL and expressed this dissatisfaction in terms of unfair compensation, occupational health, work safety, relationships with managers and work–family balance (Saraji and Dargahi 2006). They, however, expressed satisfaction in terms of social relevance. In this study, the employees were dissatisfied with their relatively low salaries and cited it as a component contributing to their low quality of work life, similar to that reported in another study conducted among nursing staff of Al-Zahra hospital (Dehaghani et al. 2012).

A perceived lack of promotional opportunities at a workplace may increase the intention to seek another job in a different setting (Islam and Alam 2014; Suadicani et al. 2013). The result from the study showed a low mean score for opportunities being made available at the workplace. This could be a result of the relatively stricter measures surrounding military establishments and the unwillingness to allow for flexibility in terms of the pursuit of professional growth outside the establishment. The same is seen in the reported mean score for space occupation. This means that the inability of the health workers in military establishments to have more control over their life/routine and the possibility of leisure and rest more than their work contributes to the low quality of work life in that area.

The results of the correlations analysis yielded a statistically significantly positive, but relatively weak, correlation between job satisfaction and the dimensions of QWL. This is corroborated by other studies (Jahanbani et al. 2018; Saraji and Dargahi 2006). The study reveals that space occupation had the highest coefficient of correlation, followed closely by working conditions, fair and appropriate salary, social relevance, opportunities component and distantly by social integration. Space occupation was an important factor affecting job satisfaction. Space occupation refers to creating a suitable working system including working hours and work schedules that will not pose a threat to the possibility of leisure and rest to the employees of the organization. It means that an organization should provide proper leisure and relaxation time to its employees so they can maintain a balance between their personal and professional life (Chmielewska et al. 2020). Hence, they should not be overburdened or pressured with extra work that will affect their work–life balance (Chai et al. 2017; Okeke et al. 2022).

The multiple regression analysis shows that some components of socio-demographic factors were able to predict QWL and job satisfaction variance. Years of experience and previous posting to war area were significant predictors of QWL, while years of experience was the only significant predictor of job satisfaction. This infers that the number of working years and non-exposure to war areas would influence the quality of work life of military health workers. A negative regression coefficient value indicated that there will be a decrease in QWL as years of experience increase. Similarly, this relationship exists between job satisfaction and respondents’ years of experience. This trend could be attributed to low budgetary allocations to the Nigerian military personnel, outdated facilities, poor welfare and an increase in banditry and insurgency over the years. A study conducted among military healthcare officers deployed to Iraq showed significant differences in the professional quality of life variables compared to those that were not deployed to a warzone (Leners et al. 2014). Constant exposure to life-demanding dangers by military personnel with less backup from the government is inimical to improving job satisfaction and quality of work life among officers.

This study prides itself as being the first, to the best of the researchers’ knowledge, to measure the quality of work life and job satisfaction of military healthcare professionals and compare their relationship with one another. It is noted that the sample size of the study is small, but that is understandable, considering that military personnel are most often under regulation not to provide responses to requests about their work lives. Nonetheless, this study has provided insight into the perception health workers have about their work and the need for stakeholders to implement strategies that would improve the same.

Conclusion

The military healthcare professionals serving in Nigeria’s Armed Forces have a fair perception of their quality of work life and job satisfaction. Their best perception of their quality of work life was on its social relevance, while the space occupation dimension had the worst perception. For job satisfaction, the military healthcare personnel scored the willingness to serve again the list value, although they were not that sad with the job. Both quality of work life and job satisfaction were related in the lives of the respondents, while years of experience on the job and being previously in a war zone were negative predictors of both quality of work life and job satisfaction.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during this study are not publicly available to protect confidentiality, but aggregated data is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abang M (2019) Nigeria’s medical brain drain: Healthcare woes as doctors flee. Nigeria News| Al Jazeera. [accessed and cited 2022 June 10]

Adebayo A, Akinyemi OO (2022) “What are you really doing in this country?”: emigration intentions of Nigerian doctors and their policy implications for human resource for health management. J Int Migr Integr 23(3):1377–1396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-021-00898-y

Adebayo ET, Hussain NA (2010) Pattern of prescription drug use in Nigerian army hospitals. Annals African Med 9(3). https://doi.org/10.4103/1596-3519.68366

Akinwale OE, George OJ (2020) Work environment and job satisfaction among nurses in government tertiary hospitals in Nigeria. Rajagiri Manag J 14(1):71–92. https://doi.org/10.1108/ramj-01-2020-0002

Akinyemi OO, Popoola OA, Fowotade A, Adekanmbi O, Cadmus EO, Adebayo A (2021) Qualitative exploration of health system response to COVID-19 pandemic applying the WHO health systems framework: Case study of a Nigerian state. Scientific African 13:e00945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2021.e00945

Awosusi O (2010) Assessment of quality of working-life of nurses in two tertiary hospitals in Ekiti State, Nigeria. African Res Rev 4(2). https://doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v4i2.58295

Bricknell M, Cain P (2020) Understanding the whole of military health systems: the defence healthcare cycle. RUSI J 165(3):40–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2020.1784039

Chai SC, Teoh RF, Razaob NA, Kadar M (2017) Work motivation among occupational therapy graduates in Malaysia. Hong Kong J Occup Ther 30:42–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hkjot.2017.05.002

Chmielewska M, Stokwiszewski J, Filip J, Hermanowski T (2020) Motivation factors affecting the job attitude of medical doctors and the organizational performance of public hospitals in Warsaw, Poland. BMC Health Serv Res 20:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05573-z

Cometto G, Campbell J (2016) Investing in human resources for health: beyond health outcomes. Hum Resour Health 14(1):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-016-0147-2

Dehaghani AR, Akhormeh KA, Mehrabi T (2012) Assessing the effectiveness of interpersonal communication skills training on job satisfaction among nurses in Al-Zahra Hospital of Isfahan, Iran. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 17(4):290

Islam MF, Alam J (2014) Factors influencing Intention to Quit or Stay in Jobs: An Empirical Study on selected sectors in Bangladesh. Stamford Journal of Business Studies 6(1):142–164

Jahanbani E, Mohammadi M, Noruzi NN, Bahrami F (2018) Quality of work life and job satisfaction among employees of health centers in Ahvaz, Iran. Jundishapur J Health Sci 10(1). https://doi.org/10.5812/jjhs.14381

Leners C, Sowers R, Quinn Griffin MT, Fitzpatrick JJ (2014) Resilience and professional quality of life among military healthcare providers. Issues Mental Health Nurs 35(7):497–502. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2014.887164

Lopes S, Chambel MJ, Castanheira F, Oliveira-Cruz F (2015) Measuring job satisfaction in Portuguese military sergeants and officers: validation of the job descriptive index and the job in general scale. Mil Psychol 27(1):52–63. https://doi.org/10.1037/mil0000060

Maksha DT, Friday NT, Stephen ON, Wilberforce NY, Hassan AB (2017) State of health care in the Nigerian military. J Family Med Health Care 3(3):52–55. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.jfmhc.20170303.12

Obinna C (2018) Nigerian Army set to restructure medical corps facilities. Vanguard News [Internet]. [accessed and cited 2022 June 2]

Ogbuabor DC, Okoronkwo IL (2019) The influence of quality of work life on motivation and retention of local government tuberculosis control programme supervisors in South-eastern Nigeria. PLoS One 14(7):e0220292. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220292

Okeke MN, Osuachala CF, Umeakuana CA (2022) Work-life balance and female employee performance in Anambra state Deposit Money Banks. International Journal of Business & Law Research 10(4):34–46

Raufu A (2002) Nigerian health authorities worry over exodus of doctors and nurses. BMJ 325(7355):65. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7355.65/b

Saraji GN, Dargahi H (2006) Study of quality of work life (QWL). Iran J Public Health 35(4):8–14 https://ijph.tums.ac.ir/index.php/ijph/article/view/2143

Saygili M, Avci K, Sönmez S (2020) Quality of work life and burnout in healthcare workers in Turkey. J Health Manag 22(3):317–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972063420938562

Suadicani P, Bonde J, Olesen K, Gyntelberg F (2013) Job satisfaction and intention to quit the job. Occup Med 63(2):96–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqs233

Sultan S, Rashid S (2015) Perceived social support mediating the relationship between perceived stress and job satisfaction. J Educ Psychol 8(3):36–42 https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1098167

World Health Organization (2007) Everybody’s business—strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43918

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants and acknowledge the hospital management for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AI, EED, AAB, MMA and BOU-K devised the study and developed/refined the main conceptual ideas. AI and BOU-K led the study protocol development, ethical application and gaining approvals, with input from the whole team. All authors undertook recruitment and data collection. EED and AAB undertook the main analysis with critical input from AI and BOU-K. BO-UK, AI, MMA and UAE drafted the manuscript. All authors helped refine the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee of the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Ituku-Ozalla, Enugu State, Nigeria. The approval number is NHREC/05/01/2008B-FWA0000245 8-1RB0002323. Permission was obtained from the authorities of the selected hospitals.

Consent to participate

All respondents gave written informed consent to participate in the study. No identifier information was requested from the respondents. All information obtained from the respondents was treated with utmost confidentiality throughout the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Isah, A., Duru, E.E., Babatunde, A.A. et al. Predictors of the quality of work life and job satisfaction among serving military healthcare personnel in the Nigerian armed forces. J Public Health (Berl.) (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-01880-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-023-01880-x