Abstract

Aim

This study assesses community readiness to prevent overweight/obesity among Ghanaian immigrants in Greater Manchester, England.

Subject and method

The Community Readiness Model (CRM) was applied using a semi-structured interview tool with 13 key informants (religious and other key community members) addressing five readiness dimensions. A maximum of 9 points per dimension (from 1 = no awareness to 9 = high level of community ownership), was assigned, alongside qualitative textual thematic analysis.

Results

The mean readiness score indicated that the study population was in the “vague awareness stage” (3.08 ± 0.98). The highest score was observed for community knowledge of the issue (4.42 ± 0.99) which was in the pre-planning phase, followed by community climate (vague awareness; 3.58 ± 0.62). The lowest scores were seen for resources (denial/resistance; 2.70 ± 0.61) and knowledge of efforts (no awareness; 1.53 ± 0.44). Findings identified structural barriers, including poor living conditions as a result of poorly paid menial jobs and high workload, contributing to the adoption of unhealthy lifestyle behaviours. Socio-cultural factors such as fatalism, hereditary factors, and social status were associated with acceptance of overweight.

Conclusion

Despite recognising overweight/obesity as an important health issue in these communities, especially among women, it is not seen as a priority for targeting change. To help these communities to become more ready for interventions that tackle overweight/obesity, the focus should initially be to address the structural barriers identified, including reducing poverty, alongside designing interventions that work with these structural barriers, and thereafter focus on the socio-cultural factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Immigrants from low- and middle-income (LMIC) countries are disproportionately affected by obesity and diabetes as compared to host populations in Europe (Agyemang and van den Born 2019). Findings from the RODAM (Research and Obesity and Diabetes among African Migrants) study show a higher prevalence of obesity and diabetes and cardiovascular disease among African immigrants in Europe, compared with compatriots in their home country (Agyemang et al. 2016). Current evidence also shows a high prevalence of obesity among people of African origin living in the UK (OHID 2021). Obesity impacts on the incidence of type 2 diabetes, cancers, and hypertension, and the prevalence is reported to be higher for women as compared to men (Agyemang et al. 2016).

The UK government has had several policies over the years to prevent obesity, and despite limited progress to date, the government has continued to show strong political commitment to addressing the high rates of overweight/obesity. The recent policy acknowledges the need to change the environment, and to empower people to make healthier dietary choices, in an effort to shift focus from curative care of obesity to prevention (Tackling obesity: empowering adults and children to live healthier lives: Public Health England 2020). The importance of the environment’s influence on health comes from ecological models of health behaviour which advocate acknowledging that individuals, their health, and their environment are interdependent (McLeroy et al. 1988). This is further supported by some of the literature which proposes community-based approaches, encompassing the context of the family, school, and healthcare environment in which obesity develops (Kesten et al. 2011). A systematic review of interventions that aim to prevent overweight/obesity in pre-adolescent girls suggests that interventions should include a broader range of social settings, supporting the potential effectiveness of approaches which focus on community settings (Kesten et al. 2011). Furthermore, there is a demand for community-tailored approaches to tackle public health issues such as obesity (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, NICE 2012). However, little is known about how these targeted approaches can be achieved in an affordable and sustainable way (Kesten et al. 2013).

Given the potential importance of community and environmental factors that contribute to obesity, the Community Readiness Model (CRM) may be an effective means of identifying tailored community-level interventions to prevent obesity (Kesten et al. 2013). CRM proposes the integration of a “community’s culture, resources, and level of readiness” (Plested et al. 2016) to effectively address community issues. “Readiness” refers to the preparedness of a group to “take action on an issue” (p 3) and can predict the likelihood that change will be achieved and be supported by communities (Plested et al. 2016). In support of the use of CRM, the NICE guidelines for working with local communities in efforts to tackle obesity, advocate engaging the community to identify local priorities and the most appropriate actions to address these priorities (Edwards et al. 2000).

CRM development and methodology has been described in detail elsewhere (Plested et al. 2016). In brief, it is based on the model of transtheoretical change (Prochaska 1992) and suggests that communities move through stages before they are ready to implement programmes, develop and deliver interventions, and take other actions to address an issue in the community. To incorporate the theories into assessing a community’s readiness, key informant interviews with community leaders are crucial because it is believed that within every community there will be people with extensive knowledge about the issue under study and the ability to suggest ways of tackling the problem (Oetting et al. 1995). The CRM to address an issue is assessed on five dimensions: community knowledge of the issue, community knowledge of efforts, community climate, leadership, and resources (Plested et al. 2016). The model was developed following expert consultation and a modified Delphi procedure that produced anchored rating statements describing a series of critical incidents needed to perform a certain task (Oetting et al. 1995). The CRM tool consists of 36 open-ended questions addressing these five dimensions.

The CRM was originally developed in the USA to address alcohol and drug abuse prevention (Oetting et al. 1995) but has been applied to multiple community health problems internationally. The model has been applied to childhood obesity prevention in the USA (Sliwa et al. 2011) and Australia (Millar et al. 2013). More recently, it has been applied to obesity prevention in adolescents in South Africa (Pradeilles et al. 2016) and adults in Ghana (Aberman et al. 2022; Pradeilles et al. 2016). However, obesity studies involving ethnic minority groups, particularly African immigrants, in the UK have seldom used the CRM, which is considered a suitable approach for understanding how ready community members are in addressing health and/or social issues in their communities (Edwards et al. 2000). It is for this reason that this study was needed to explore the views of Ghanaian immigrants’ resident in Greater Manchester regarding the problem of obesity, and their readiness to embrace and support policies/interventions to tackle the problem.

Thus, the aim of the current research was to assess the stage of community readiness to prevent overweight/obesity among Ghanaian immigrants in Greater Manchester, England. The results from this research will inform the design of tailored community-based interventions to tackle the problem of overweight and obesity.

Methods

This research was conducted in Greater Manchester in the Northwest region of the UK. Greater Manchester is a region with nearly 3 million people. According to the 2011 census, the total Black (African and Caribbean) population is almost 3% (Office for National Statistics 2014). Greater Manchester was selected because the prevalence of obesity is significantly higher than the national average, with 63% of adults estimated to be overweight/obese. Current adult obesity prevalence data show an increase from 23% in 2003 to 29% in 2017 in England (Council MC 2022). The rates are particularly high among Blacks and other minoritised communities. For instance, in 2020, 67.5% of Black adults in the UK were overweight or obese — the highest percentage of all ethnic groups (Edwards et al. 2000). According to the census data, Ghanaians are one of the largest immigrant population groups from Sub-Saharan Africa living in the UK and Greater Manchester (Office for National Statistics 2014).

Data collection

Previous work in the UK (Agyemang et al. 2015) suggests that involvement of Ghanaian community leaders from religious groups and local key community members enhances study participation and could help promote understanding about the relevance of the study. Purposive sampling was therefore used to recruit key informants into the study from religious and ethnic groups using information sheets and mobile phone calls and through snowballing techniques. Other key informants were identified by the lead researcher (HO-K) through personal contacts within the Ghana Union Greater Manchester Branch.

Key informants in this study were therefore religious leaders such as elders, pastors, leaders of Muslim groups, hometown leaders, chiefs, and a queen mother (a powerful female leader who plays an important role in local government), and leaders of the Ghana Union of Greater Manchester.

Participants were eligible if they were ≥ 18 years, resident in Greater Manchester and self-identified as Ghanaian. Recruitment ceased when preliminary analysis revealed that no significant new issues emerged. Ethical approval for the study was obtained in January 2021 from the University of Sheffield.

Prior to interviews, participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity. Participants were told that they could withdraw before, during, or after data collection without any negative consequences. Interviews were conducted by the lead researcher (HO-K), who has extensive qualitative research experience (see, e.g., Osei-Kwasi et al. 2017 and 2019), between September and November 2021 either via mobile phone or virtually using Zoom because of the ongoing COVID pandemic in the UK at the time. Interviews were conducted mainly in English: however, some participants preferred to provide responses both in English and the Ghanaian language, Akan Twi (HO-K is fluent in Twi and English).

The interview guide was adapted from the CRM questionnaire to suit the aim of the study as recommended by the authors of the CRM tools (Plested et al. 2016). The CRM was first piloted with two community volunteers. As a result, the tool was adapted by rephrasing of sentences and altering of terminologies (S1 Table).

Data analysis

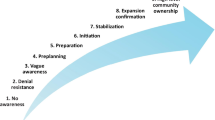

All key informant interviews were recorded with permission from participants using a digital audio recording device. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and where necessary translated, reviewed for accuracy, and scored by two independent scorers (HO-K and RA) following the CRM handbook (Plested et al. 2016). Prior to scoring, respondent validation was undertaken by discussing a sample of the transcripts for accuracy, and resonance with responses provided by two of the key informants via a phone call. Each transcript was read through thoroughly in full to gain a general idea of the content. For each of the five dimensions of the interview guide, there are nine anchored statement ratings. Each transcript was read systematically and compared to the most appropriate anchored statement in the handbook corresponding to a level of readiness on a scale from 1 (no awareness) to 9 (high level of community ownership). Once all transcripts had been scored, the average score for each dimension was calculated and a score for each key informant was calculated. Then the overall average was calculated by adding the scores across all of the interviews and dividing by the number of interviews. To calculate the overall community readiness score, the average of the five dimensions was calculated. The overall mean score was then compared with the nine stages of community readiness as depicted in the CRM handbook (Fig. 1), to assess the level of readiness of the community.

After scoring, thematic analysis was conducted using NVivo. To identify themes, a combination of inductive and deductive approaches was employed. HO-K conducted line-by-line coding to generate initial ideas that were later built into sub themes. A priori themes informed by the five dimensions of readiness served as themes, while new explanations that emerged from the interview transcripts were used to develop sub themes.

Three of the transcripts were independently coded by a second coder (RA) and final codes were agreed upon discussion. The codes were consolidated into a number of themes that were applied to all subsequent transcripts (S1 File).

Results

Thirteen key informant interviews were conducted with nine males and four females. Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the key informants interviewed from the Ghanaian community in Greater Manchester. Duration of stay in the UK ranged from 4 years to over 40 years since migration.

Community readiness scores

The mean community readiness score for Ghanaian immigrants in Greater Manchester was (3.10 ± 0.98) which corresponds to vague awareness (Table 2). This stage corresponds to the third lowest of the nine stages of community readiness. The vague awareness is reached when: i.) a few community members have at least heard about local efforts but know little about them, ii.) the leadership and community members believe that this issue may be a concern in the community, but they show no immediate motivation to act, iii.) the community members have only vague knowledge about the issue (e.g., they have some awareness that the issue can be a problem and why it may occur), and iv.) there are limited resources (such as a community room) identified that could be used for further efforts to address the issue.

The highest score was seen with community knowledge of the issue (4.42 ± 0.99) which was followed by community climate with a score of (3.58 ± 0.62). The lowest scores were observed for resources (2.7 ± 0.61) and knowledge of efforts (1.53 ± 0.44).

Community knowledge of efforts

Community knowledge of efforts raises the question “How much does the community know about current programmes and activities to address overweight or obesity within the Ghanaian immigrant community in Greater Manchester?” The score for this dimension was the lowest (1.53) which suggests that only a few members have any knowledge on current programmes and activities or local community efforts in place to address overweight/obesity for the community. The following themes were used to interpret the community knowledge of effort score: other priorities, individual efforts, and socio-cultural factors.

Other priorities

Although most key informants stated that overweight/obesity was of concern to the Ghanaian community, the low score suggests that there was no knowledge of local efforts specifically addressing overweight/obesity for their community. From the qualitative data, participants mentioned health seminars that had been organised on other health issues, such as on cancer, blood pressure, and diabetes, but not overweight/obesity.

“As I said earlier, we haven’t discussed anything, but it’s a concern for us. Personally, I need to reduce the size of my stomach. We have discussed blood pressure, stroke, and sugar. We get the nurses, but we haven’t tackled overweight” (#1, leader of an ethnic group).

Two key informants mentioned efforts by general practices (GP) and Slimming World targeting weight loss. There was also the mention of the Caribbean and Health Network by one key informant and the recognition of ongoing nutrition education sessions on social media.

“At the moment the efforts are at the GPs. For example, when I got to 40 onwards, every year I went for check-up, and I realised my sugar was going up, BP was going up, and my weight was also going up, so I needed to look at two things, diet. Are you eating too much sugar or salt, so I realised I had to cut down” (#4, leader of an ethnic group).

Generally, the interviews suggest that addressing overweight/obesity is not deemed as a priority by the Ghanaian community. Participants considered social events like funerals and birthday parties were more important. For instance:

“Like the way we plan for parties, funerals, no, we haven’t planned anything that will look at our diets or obesity. Even though that’s what is killing us, we don’t focus on that” (#3, local key figure).

Individual efforts

According to majority of the key informants, very few people were engaging in any activities to address the problem. For those who were motivated to take action, this was reported to be undertaken at the individual level, by for instance, subscribing to a gym, making dietary changes, and listening to talks on social media. For example:

“When we talk about obesity itself, I haven’t heard of any programme but individually people are talking to each other, people are taking courses at home and doing exercises” (#10, pastor).

Socio-cultural factors

All key informants indicated that although overweight/obesity is an issue it is not prioritised in the community because of various reasons: cultural acceptance of overweight/obesity, higher social status attached to overweight, and time constraints making it hard to do anything to tackle overweight/obesity due to busy work schedules. Some key informants used expressions like “our culture” and “as Ghanaians” in describing the cultural acceptance and preference for overweight. For instance:

“I think most people know that it’s not right but, in our culture, people think when you are slim or thin then you are not well. But people know it’s not right. (#7, leader of an ethnic group).

Furthermore, overweight/obesity was also described as a sign of good living by some Ghanaians. For instance:

“So, within the community, people on the bigger side are seen as a sign of good living. It is not really highlighted as a problem until it becomes critical, and hospitalisation is involved”

Some factors associated with being an immigrant, and trying to settle in a new environment and poor living conditions were also identified by key informants as this quote illustrates:

“So, it is important to us, but our living conditions as immigrants does not allow for us to focus on it [obesity]." (#3, key informant)

Consequently, the need to take action is only apparent when it becomes critical and severely affects people’s health rather than thinking about prevention as an option.

Leadership

The leadership score was 3.35, which suggests that the Ghanaian community leadership believes that overweight/obesity may be a concern in the community; however, it may not be seen as a priority because leadership shows no immediate motivation to act. Key informants revealed that although they know it is an issue, they have not prioritised it as this quote illustrates:

“Hmmm, we think about it but we haven’t taken action to take this forward” (#2, queen mother).

All key informants interviewed noted that they and other community leaders will actively support efforts once they have understood the need and will mobilise their group members to get on board. However, a lot of awareness needs to be created among the community members about the need to take action. For other groups, like churches, the hierarchical structure means all directives had to come from the church headquarters. Thus, for any effort to be undertaken it must get the support from national headquarters before it can be supported at the community level.

There were conflicting responses to support for expanding efforts to other groups. For some churches due to competition, the leaders did not think scaling up would be possible even if there was interest. For instance:

“No, no because we don’t even communicate amongst ourselves as different churches because of competition in terms of membership. Some will feel like you are trying to poach their membership. So, scaling it up to the community will be very difficult.” (#11, church elder).

For others, this would depend on the level of education the leadership have, suggesting that leaders with higher education would support scaling up because they understand the need for this and are motivated to do so. Others stated that once it was initiated people would embrace it, support it, and would scale-up efforts because of the perceived benefits.

“Most of us know that obesity is not a good thing, we just need someone who will lead or initiate it, so as soon as someone comes to lead it, there will be so many people who will support it or contribute in different ways “(#5, leader of an ethnic group).

Socio-cultural factors

Three sub themes emerged: the role of the church, living conditions of Ghanaian immigrants, and social support. According to two key informants interviewed, the church just focuses on spiritual development and not physical health, and therefore addressing overweight/obesity was not important to leadership, as this quote illustrates:

“There has never been any seminar, or any preaching on the pulpit about this issue, since my 20 years that I have been with them. It’s all about the spiritual development only, nothing about the physical health” (#11, church elder)

In contrast, a pastor interviewed emphasised the need for good physical health as part of spiritual growth, and therefore stated that he incorporated the need for a healthy lifestyle in his sermons.

Participants also highlighted the poor living circumstances of most Ghanaian immigrants living in Greater Manchester, which was perceived as discouraging leadership from planning other activities. Poor living conditions referred to types of jobs and work schedules—menial jobs such as cleaning and working long hours coupled with the stress associated with trying to settle in the UK. The leaders are aware of these conditions, and assume that organising other programmes in addition to church service may overburden such people, as this quote illustrates:

“I don’t like to put pressure on people who are already under pressure (from work and trying to settle in as immigrants). Even in church when I ask people to become ushers, or volunteer to play keyboard, they moan. So, it makes it difficult to get things done.” (#11, Pastor).

Furthermore, one participant stated the internal conflicts within the leadership of the Ghanaian Union were an obstacle to focusing on important topics like this.

“Because of all the issues (conflicts) going on in the leadership, there is no transparency at the moment. When I was involved in the union, we put a lot of emphasis on health issues, and I believe if we have a good proposal and bring this to the community we will have people ready to support it.” (#6, Ghana Union leader).

Some participants suggested that the social support that exists within the African community will facilitate engagement in programmes, as people like to support one another.

"As Africans we always look after one other, so some may not even be interested in it [programmes to address overweight/obesity] personally, but because they care about other community members they may participate" (#8, Muslim leader).

On the contrary, a participant was of the view that only a few leaders will be willing to put in the commitment to ensure the sustainability of efforts. According to her, there was the need to motivate people to get involved and described this as a challenge.

"I think it’s just a few that will be willing to put the commitment in, to constantly drive the initiative, create the awareness, and motivate people. So, one of the key issues will be how to motivate community members to really get involved. That’s the challenge" (#13, Muslim women’s group leader).

Community climate

The third dimension — community climate — considers the community’s attitude toward addressing the issue. The score for the community climate was 3.58, at the vague awareness stage which in accordance with the CRM handbook suggests that some community members believe that overweight/obesity may be a concern in the community, but it is not seen as a priority, and they show no motivation to act.

The following themes were used to interpret the score: prevention not a priority and socio-cultural factors.

Prevention was not a priority

There were conflicting opinions expressed on the community level of concern on overweight/obesity. It appears to be a concern for some participants even if nothing was being done about it, and a priority when people are diagnosed with a chronic illness where obesity is a risk factor. However, overall, findings suggest prevention is not seen as a priority.

According to key informants, obesity was perceived to be more of a problem among the Ghanaian women compared to the men. Participants indicated that some women who were concerned about this and the risk to their health were taking some steps to lose weight and stay healthy. According to one key informant, a few women who were also taking actions to lose weight did so because they felt stigmatised in church which had affected their self-esteem.

“I think it is very much of a concern. They think about it a lot, for instance go to the gym. It is a big concern for a lot of women” (#2, queen mother)

A few participants reported that members of their groups take individual steps for instance, by going to the gym, but generally it was perceived that the issue was not taken seriously by most of the Ghanaian community. Some of the reasons highlighted included the cultural acceptance of overweight and the social status associated with overweight i.e., it is a sign of good living. Therefore, it was only highlighted as a problem when it becomes critical and severely affected people’s health.

"We Ghanaians naturally tend to be big but we don’t get the time for ourselves" (#1, leader of an ethnic group).

Furthermore, the nature of the jobs that most Ghanaians were perceived to be engaged in was highlighted as contributing to an unhealthy lifestyle, which is associated with overweight/obesity.

"Our jobs are on and off as Ghanaians. A White man knows he works from 9 to 5pm, but the time we use in working, doesn’t help. That also affects our dietary behaviours. Our jobs tend to be warehouse, cleaning, we have very few people doing office jobs, so depending on the job, someone might eat around 12 in the night, and then after work come home and just sleep" (#3, key informant).

Whilst discussing the potential for community engagement, key informants indicated that a few community members would support efforts to prevent overweight/obesity, especially those who think their lives have been impacted by it or are at risk. However, even fewer people would be willing to put in the commitment to constantly drive the initiative. For example:

“Maybe a few…people whose lives are being impacted will take it up (#11, church elder)

“A few people will do that. I think it’s just a few that will be willing to put the commitment in, to constantly drive the initiative, create the awareness, and motivate people.”. (#13, Muslim women’s group leader)

Further, it was believed that generally most people will expect anything to do with disease prevention to be free and they would therefore not be willing to pay to take part in initiatives. People will prioritise paying or contributing to other social events like funerals. Only a few may be willing to support with money once they are convinced about the benefits.

“I don’t think anyone will pay for it, if the church is willing to take it up and then fine, if not for individuals, it is not in the Ghanian DNA to pay for something like that. They don’t see the need to do anything outside of their jobs, and church. For instance, people die and there is a burden on the church, so I have told people, educated them, given them life insurance and funeral plans, the uptake is .0000%, people are not receptive to things that are important to their own life” (#11, church elder).

Social support

Key informants stated that the social support that exists within the Ghanaian community will facilitate engagement, as people want to support one another in any way that they can. Some members share social media videos on health topics on the community WhatsApp platform so others can benefit from it.

"Like I am saying, the project (social media video on health) that was shared onto the platform was not initiated by a leader, but a member, so that shows that it’s important to them" (#5, leader of an ethnic group).

Cultural acceptance of overweight

According to some key informants, being overweight is perceived as part of the Ghanaian culture and this acceptance together with other misconceptions (to be discussed) were highlighted as barriers to prioritising the prevention of overweight/obesity. However, this may not be the case for the more educated community members, as this quote illustrates:

"It is divided opinion, some people especially the educated ones think it’s a problem, so it needs to be tackled, but on the other hand, others think it’s not a problem, because culturally, we think if someone is obese, it's seen as good, and it’s not a problem. Those who think it’s not a problem, don’t know the consequences of obesity ,and that is concerning, because it is our cultural representation of obesity” (#5, leader of an ethnic group).

Even when activities have been organised locally, it was reported that participation was low as in the case of a women’s fellowship fitness activity that focused on cooking and exercise. Another possible explanation for the low engagement discussed was the recurring issue to do with work schedules of Ghanaian immigrants because these schedules do not allow them to fit in any other activities. For instance, engaging in manual jobs and having night shifts means that one will need to sleep during the day and eat late at night which contributes to the problem.

Community knowledge of the issue

This dimension is concerned with how much the community knows about overweight/obesity. The readiness score for knowledge of the issue was the highest (4.42) of all the dimensions. This result suggests that at least some community members know a little about causes, consequences, signs, and symptoms of overweight/ obesity. In addition, at least some community members are aware that the issue occurs locally. Factors identified were mainly at the individual level. The themes that emerged were unhealthy dietary behaviours, physical inactivity, lack of knowledge, and experience of living with obesity. Other socio-cultural factors were cultural acceptance of overweight and misconceptions such as ‘being fat’ was a sign of good living.

Key informants indicated that unhealthy lifestyles, such as late-night eating and a lack of physical activity, were the causes of overweight/obesity and this was seen as widely known by the community. For example:

“Most people are beginning to understand that they don’t have to eat fufu late in the night, otherwise they will put on weight. Some ideas are there” (#11, church elder).

In contrast, two community leaders did not think that the Ghanaian community was well informed about the causes because unhealthy behaviours persist.

“We know nothing about the causes, if we know, we will not be eating certain foods we are eating” (#6, leader of an ethnic group).

There was disagreement on the prevalence of overweight/obesity in the community and how much the community knows about it. Some key informants thought community members’ perceptions on weight differed for different people:

“Some people are naturally big, some medium, so most people know when they are obese and do something about it…but when they get the education they will improve” (#1, leader of an ethnic group).

According to key informants, what is easily recognisable is the extreme cases (i.e., morbid obesity) but overweight may not always be perceived, as this quote illustrates:

“If one is too fat, people can tell, but if it’s just a little they cannot tell (#6, leader of an ethnic group).

Perceptions of knowledge on the prevention of overweight/obesity varied. It ranged from no knowledge of prevention to a lot of knowledge. Responses suggest that those who were well informed about how to prevent overweight/obesity were those who have experienced it and the people around them.

“People are beginning to realise that, if you eat late in the night or if you eat a lot of meat, so it’s all coming out, this is because of the seminars we have on diseases on other things. So, people are becoming aware, especially people who are so obese and can’t climb the stairs and come to church. So heavy that it’s impacting their hips and knees. Some come to church in crutches. So, people have become aware that if you become overweight you will experience such problems. The awareness is coming gradually” (#11, leader of an ethnic group).

Misconceptions about obesity

Key informants had mixed views about whether misconceptions still existed within the Ghanaian community. These were perceived as cultural or superstitious. For instance, ‘being fat’ was acceptable in the community because of the social status linked to it indicating wealth and good living. Some were fatalistic, suggesting that ‘being fat’ was one’s natural disposition or that it is hereditary, and nothing can be done about it. For example:

“It’s seen as sign of good living, being overweight is hereditary and there is nothing they can do about it, it’s just in our family, and especially among women, it is an expectation when you start having kids, there is not much awareness that it can be corrected or something can be done about it” (#13, leader of an ethnic group).

Furthermore, it was suggested that Ghanaian immigrants had other priorities and did not care so much about their eating habits, but would rather pay attention to their appearance in terms of clothes and building properties as this quote illustrates:

“As people think they have a natural predisposition to be a certain weight, and we do not pay much attention to our food and eating habits as we should, we perhaps pay more attention to our appearance. And a classic one is, I remember I went to this place, where people were all wearing £70 hat, but they were eating burgers from Iceland [a discount food outlet], and that’s where they shop. These are Ghanaians. Interesting, but generally Ghanaians we tend to buy our foods from the cheapest places, and we want to use our money on other things rather than food. Building houses, saving our money, clothes” (#9, leader of an ethnic group).

Others attributed being obese with superstition, praying about it rather than taking action to lose weight:

“Most African communities will associate everything to superstition. So, when someone is obese, instead of using good nutrition, they may attribute it to superstition and pray about it” (#8, Muslim leader)

Lack of information

Almost all participants agreed there were no sources of information on obesity as a condition within the Ghanaian community. A few mentioned the news, social media, or their GP. However, the general view was that even when these are available, most people will not access them or make the effort to go and find any resources because it was not perceived as a big problem. It was stated that people would prefer to listen to a presentation because they do not have the time to read through brochures or may not be well educated to comprehend the information. A participant also mentioned others learn from experience, i.e., seeing others or themselves get affected by overweight/obesity.

Maybe brochures, but I think what I have observed in our community is that people don’t have time, so they won’t have time for those resources, they prefer to just listen to one time talk, and most people don’t have much education, so they would prefer to just listen to talk, the last woman I invited brought her blackboard, posters and pictures to illustrate her talk, and I think they appreciate those ones more than having to read documents or brochures. (#1, leader of an ethnic group)

Resources related to the issue

The CRM suggested that there are limited resources available that could be used for further efforts. There was no action to allocate these resources to this issue. Funding for any current efforts was not stable or continuing.

Funding, donations, and grants

Participants were either not aware or stated no/very little funding (either locally or more generally from the council) was available for programmes to prevent overweight/obesity. Although one participant stated that members have made contributions to support a previous event, they had organised to get a talk by an expert, most participants seem to suggest that once the community groups made it a priority, they will allocate funding to it as they do with other projects.

Three NGOs were mentioned by three different participants (Humanity first, Jesuscina foundation and Sahara Nutrition). Other participants did not know of any NGOs within the community.

Similar to funding, some participants were not aware of any financial donations and others stated they were not receiving any. One religious leader indicated how the church has funds, but this may not be used for such programmes because it’s not a priority. No participants were aware of any grants except for one, the director of an NGO who indicated that they had applied for some grants in the past and had not been successful.

“You won’t get donations within the African community, but from the other side (non-African organisations), there are some donations” (#6, leader of an ethnic group).

“Not at all, if something is going to come from the church fund, it should come from the top, headquarters, but since it’s not their priority it won’t be used and people don’t know that the city council is a potential source of funding” (#11, leader of an ethnic group).

Volunteers and experts

There were a lot of community members that would volunteer to help, if recruited for a programme, especially the youth. One key informant emphasised the need for incentives to motivate volunteers, and another suggested that volunteers may begin helping but may not continue to help throughout a programme. On the contrary, a participant indicated that because most immigrants struggle with issues in trying to settle, it is difficult to ask them to volunteer for free.

“Because most people have their own problems and others are now trying to find their feet here in Europe so asking people to do this for free is not easy. Asking them to leave their work and family to do something totally different for free is not easy (#11, Pastor).

There was disagreement on whether there were experts within the community. Some stated there were none while others said there were nurses, medical doctors, and nutritionists within the community who could educate people on how to prevent obesity.

Two participants who were health professionals lamented that, although they had the capacity to do education to prevent overweight/obesity, the community has not given the opportunity, because it is not perceived as a big problem.

"They know I am a nutritionist, but they have never called me to do a talk” (#12, leader of an ethnic group).

"There are medical doctors, who give seminars here and there when they are given the time, again it has to come from the time. And we have annual health week. Never have we actually talked about overweight and obesity. There are few professionals who can do it but if you are not given the chance, you can’t" (#11, leader of an ethnic group).

Space for action

All participants were of the view that space was available for any efforts or programmes to address the issue. This could be rented space, or the properties owned by religious institutions and other groups. Even when it was rented, they stated that the space could be utilised for programmes, particularly if it was embedded in the usual meetings of these groups.

“We have some space. It’s not a problem, we have our own place that take over 200 people” (#11, church leader).

“I think, what we can use…in our association, we can embed it into our meeting, and when people come for the meeting, it becomes part of the events. Other than that, Ghana community is planning to have its own space. It’s in the pipeline, I believe when that is completed, then we can have that space” (#5, leader of an ethnic group).

Action or inaction to mobilise resources

Generally, responses suggest that little to no effort is being made to allocate resources to prevent overweight/obesity, except for one participant who stated that the Ghana Union in the past mobilised resources and collaborated with the local council for various activities aimed at improving the lives of Ghanaians, and this route could be leveraged to tackle the issue:

“In the past we have worked in conjunction with the Manchester social services council in Manchester. We used to have Ghanaians working there, and we tap into those resources. The city council recognised Ghana Union as an organisation so with new leaderships, we can have health topics. And the city council can support “(#7, leader of an ethnic group).

There was agreement that there will be support from the leadership and the community once more awareness was created on the need to prevent overweight/obesity. Even though the issue is not a priority, it was recognised as a concern, and responses suggest that once efforts are for a good cause that will benefit the community, there will be no opposition by leadership or the community members:

“Yeah, they will support, sure. Because like I am saying they know that obesity is not good, especially the educated ones, though we know it’s not good, some think it can be natural, which is the negative associated to it. So, since people know it’s not good, they will support it”. (#7, leader of an ethnic group).

Discussion

This research assessed the stage of community readiness to prevent overweight/obesity among Ghanaian immigrants in Greater Manchester. While similar studies have been conducted in high-income countries (Findholt 2007; Sliwa et al. 2011), in Africa (Aberman et al. 2022; Pradeilles et al. 2016 and 2019) and among other 'minoritised’ communities in the UK (Islam et al. 2018), this is the first study to apply CRM to a Ghanaian immigrant group, making relevant comparison with other Ghanaian immigrant groups difficult. However, in the absence of similar studies, it is useful to make comparison with similar populations in different settings. The operant model of acculturation (Landrine and Klonoff 2004) suggests the need to understand the context of the country of origin to be able to understand immigrant health behaviour and therefore, findings of this study will be discussed first by comparing with Ghanaian CRM studies (Aberman et al. 2022; Pradeilles et al. 2019) and other minoritised communities (Islam et al. 2018).

In the present study, the highest score of 4.42 was seen with community knowledge of the issue which assesses how much the community knows about overweight/obesity. This indicates that the Ghanaian communities in Greater Manchester are in the pre-planning stage wherein at least some community members know a little about causes, consequences, signs, and symptoms. By comparison, the readiness scores for the study conducted in Ghana (Aberman et al. 2022) were lower (Hohoe 2.87 and Techiman 2.54), indicating that both communities are moving towards stage 3, wherein they have some knowledge about the issue and how to avoid it but do not prioritise it or appreciate the associated health risks. Findings from the two communities in Ghana suggest that although some information has been disseminated in Ghana, this was not sufficient to support deeper understanding of the health risks associated with overweight/obesity. This difference in scores of the level of awareness raises questions about the effects of migration on health literacy. Are Ghanaian immigrants exposed to more information on the issue or are they selectively different? Another possible explanation could also be differences regarding the stages of nutrition transition between Ghana and the United Kingdom. The two communities in Ghana, like many communities in low- and middle-income countries, may be described as being in the early stages of the nutrition transition (Popkin 2004), whilst the UK may be described as being in the advanced stage of the nutrition transition. Although, in the present study the reported level of awareness did not indicate that the Ghanaian immigrant community has necessarily changed dietary behaviours towards healthier ones, in another CRM study to address obesity in a minoritised community, i.e., Roma communities in the UK, an overall score of 3 was reported, also indicating vague awareness about the issue (Islam et al. 2018). However, unlike the present study, the highest score was reported for community efforts and knowledge of efforts, indicating that most key informants acknowledged a variety of services that had been made available to tackle obesity within their communities. Community knowledge about obesity scored low, indicating denial/resistance. This implied that while the interventions were available, they had not yet penetrated the Roma communities.

In the present study, it was suggested that more highly educated people were most aware of the causes and consequences than less educated participants, which concurs with findings from the CRM study conducted in Ghana (Aberman et al. 2022) that reported the wealthy to be more likely to understand the causes and risks associated with the issue. Wealth is often associated with increased education, and both are very important factors that have been shown to influence lifestyle behaviours amongst different populations (Gissing et al. 2017; Ismail et al. 2022; Osei-Kwasi et al. 2016).

It is important to note that, although price is considered to be a barrier to healthy eating (Osei-Kwasi et al. 2016), in our study, affordability was not mentioned although indirect reference was made to Ghanaians choosing cheaper foods and prioritising other goods over food expenditure. Unhealthy dietary habits, such as the consumption of energy-dense foods, which was perceived as part of Ghanaian traditional diets and late-night eating, were referred to as drivers of overweight/obesity. Late-night eating, however, was perceived as unavoidable due to the kinds of jobs many Ghanaian immigrants in Greater Manchester engaged in. Earlier studies among Ghanaian immigrants in Greater Manchester have reported that many people engage in two or three menial jobs that do not pay well, taking night shifts, and these have been highlighted as barriers to the adoption of a healthy lifestyle (Osei-Kwasi et al. 2017 and 2019). This pattern of work is further supported by a survey conducted in London focusing on Ghanaian and Nigerian immigrants employed in low-paid sectors (Herbert et al. 2006). Findings showed that most respondents in the study engaged in cleaning jobs while others were employed as care workers. The survey also reports that 94% of Ghanaians who participated earned less than the minimum wage (£6.70/hour) in 2008 (Herbert et al. 2008). It is worth emphasising that the survey only focused on low-income earners and thus cannot be generalised to all Ghanaian immigrants. Studies have shown that many Ghanaian immigrants integrate into the UK system by educating themselves and applying for high-paying jobs (Orozco et al. 2005). This study also showed that most Ghanaian immigrants had a financial obligation to remit money back to family in Ghana towards supporting family members and securing property. This was prioritised and thus had implications for access to healthy foods. This finding has been corroborated in an earlier study conducted amongst Ghanaian immigrants (Osei-Kwasi et al. 2017) and among immigrants in Australia (Koc and Welsh 2001), which shows the importance placed on the extended family system within the community.

Previous studies have highlighted the urban food environment and the increase in fast-food chains to be important dietary causes of overweight (Pradeilles et al. 2019; Gissing et al. 2017); however, there was no mention of this in our study. A possible explanation may be that most Ghanaian immigrants do not necessarily eat out or buy fast foods, unless they were buying to prepare at home (Osei-Kwasi 2017). Previous studies have shown that Ghanaians continue to cook and eat traditional foods (Osei-Kwasi et al. 2017), as this is important in maintaining Ghanaian cultural identity.

Overweight/obesity were generally perceived to be of concern especially among women. It was suggested that although acceptability and desirability of overweight women persists within some members of the community, most people were now aware that this needed to change. Similarly, findings from a study conducted in Ghana (Aberman et al. 2022) indicates that overweight/ obesity were overwhelmingly described as acceptable or desirable in both communities until it impacted on health negatively. Acceptability of overweight among many African women has been reported in a recent systematic review, which concluded that most studies on body size preferences for adolescents and women living in Africa reported a preference for normal or overweight body sizes (Pradeilles et al. 2022).

The readiness score for leadership in this present study suggests that leadership believes that the issue may be a concern in the community, but they show no immediate motivation to act. Religious leaders highlighted obstacles that members faced as immigrants and how this could affect additional efforts or activities organised. On the contrary, findings from the CRM study in Ghana showed health promotion activities were being championed by religious leaders (Aberman et al. 2022). Across both settings in Ghana, localised efforts such as fitness clubs and health talks were commonly implemented, although they may not be targeted at tackling overweight or obesity. These were perceived as affordable and integrated into existing activities often organised by churches. Although churches are increasingly recognised as popular settings for implementing health promotion programmes (Campbell et al. 2007; Ammerman et al. 2003; Corbie-Smith et al. 2003), the present study showed that churches or mosques in Greater Manchester are currently not spearheading any specific activities to prevent overweight/obesity. Given the extant evidence on health promotion using church settings, the present finding could be because these types of church-based interventions just have not found their way to Manchester yet, so the church leaders do not have an example of what can be done, or it could be an artefact of the limited number of church leaders interviewed. There is therefore a need for research to further explore the potential to use religious settings for obesity prevention within the UK-based Ghanaian community, as these are important social institutions that can reach lots of individual and families.

The readiness score for resources in this present study suggests that there is no dedicated funding or action allocated to address the issue. This is not surprising given that overweight/obesity are not prioritised within this community, but also because most people may not have the financial latitude to contribute to such programmes. However, key informants suggested that the community had some untapped potential, for instance there were experts such as doctors, nurses, nutritionists, and other health workers within the Ghanaian community who could be engaged in interventions to address the issue.

In this study, ‘knowledge of efforts’ had the lowest score of 1.35, which suggests that the community had little or no awareness about local community efforts to address the issue. Very few people stated the GP surgery as a resource, although it was perceived that most people will not patronise these, due to work commitments. These are structural barriers that need to be addressed for such interventions to be inclusive.

Over the years, there have been several policies and strategies to address obesity. In 2020, the UK government announced a new set of policies to tackle obesity alongside a “Better Health Campaign” (NHS 2022: no date for campaign). This campaign aims to reach millions of people to lose weight and make behavioural changes to prevent diseases. However, this has been criticised as being flawed as it does not address the complex underlying causes of obesity such as environmental and socioeconomic factors. Critics have accused the UK government of putting the blame on citizens for the obesity epidemic, rather than tackling its root causes (LifeConnect24 2020).

The present study supports this criticism. The study population is clearly an example of a group for which a simplistic message of eating less and moving more is not enough because, except for a few people, most in the community may not be able to do anything with the message. People on low income often have more pressing concerns than losing weight, which may explain why overweight/obesity is not a major concern in this study. Greater Manchester declared itself as a Marmot region in 2019 and worked towards developing a sustained programme of action on health inequalities and inequalities in social determinants (Marmot 2020). The Manchester Healthy Weight strategy has a vision to create an environment and culture where all people of Manchester have the opportunity and are supported to eat well, be physically active, and achieve and maintain a healthy weight (Council MC 2022). Its aim is to reverse the rising trend of overweight and obese children and adults in Manchester utilising a whole systems approach. It has four strategic themes: food and culture, physical activity, prevention and support, and environment and neighbourhood. Current policies at the national and local levels targeted at obesity including the Manchester Healthy Weight strategy (Council MC 2022) are clearly not reaching minoritised communities such as the Ghanaian community included in this study, as evidenced by the very low scores for community knowledge of effort observed.

An important question our study raises is: how do we help this community to become more ready for interventions that tackle overweight/obesity? Although education may still be relevant, there is a need to address the recurring structural barriers highlighted in this study, such as low pay, poor living conditions, and long working hours in multiple jobs should be priority. These structural barriers are risk factors for obesity, so policies should aim to work with communities to find ways to intervene that work with their structural barriers.

Strengths and limitations of the CRM model

This study is the first to assess the stage of community readiness to prevent overweight/obesity among a Ghanaian immigrant community. The qualitative thematic data that complemented the quantitative scores has provided important contextual information that can be leveraged to plan, design and implement effective interventions for the Ghanaian immigrant community to tackle overweight/obesity in the future.

While the views of the 13 key informants may be perceived as small and not be representative of Ghanaian community groups in Greater Manchester, each key informant was carefully selected to represent a distinct sub-group within the community, and the number of interviews in this study is in line with what is recommended in the CRM handbook. Also, given the disagreements in the literature about who community leaders and key informants are (Marshall 1996; Poggie 1972), participants were therefore selected from different ethnic and religious backgrounds, and varied in age and gender. Thus, this study has a good coverage of the variety of groups and demographics within this study population.

Furthermore, the scoring systems used, as defined in the CRM handbook, have been criticised (Kesten et al. 2015) for the potential of researcher subjectivity. To reduce this potential bias, however, the CRM interviews were scored independently by two researchers, and all discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached. Finally, by focusing only on key informants, the CRM can be criticised for placing undue responsibility for tackling obesity on the community rather than on other institutions and government actors with whom responsibility is shared.

Conclusion

The CRM assessment suggests that this community is in the ‘vague awareness’ stage for prevention of overweight/obesity. Despite recognising overweight/obesity as an important health issue in the Ghanaian immigrant community, especially among women, it is not seen as a priority. Thus, there is an urgent need for interventions to be implemented to tackle overweight/obesity amongst this population. For such interventions to be successful, however, there is a need to support the community to become ready. This study concludes that the initial focus should be on addressing the structural barriers to community readiness, including reducing poverty and addressing living conditions, alongside designing interventions that work with these structural barriers and thereafter focus on the socio-cultural factors, such as body-size preferences.

References

Aberman NL, Nisbett N, Amoafo A, Areetey R (2022) Assessing the readiness of small cities in Ghana to tackle overweight and obesity. Food Security 14:381–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01234-z

Agyemang C, Van den Born BJ (2019) Non-communicable diseases in migrants: an expert review. J Travel Med 26(2):tay107. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/tay107

Agyemang C, Beune E, Meeks K, Owusu-Dabo E, Agyei-Baffour P, Aikins Ad, Dodoo F, Smeeth L, Addo J, Mockenhaupt FP, Amoah SK, Schulze MB, Danquah I, Spranger J, Nicolaou M, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Burr T, Henneman P, Mannens MM, van Straalen JP, Bahendeka S, Zwinderman AH, Kunst AE, Stronks K (2015) Rationale and cross-sectional study design of the Research on Obesity and type 2 Diabetes among African Migrants: the RODAM study. BMJ Open 4(3):e004877. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004877

Agyemang C, Meeks K, Beune K, Owusu-Dabo E, Mockenhaupt FP, Addo J, de Graft MA, Bahendeka S, Danquah I, Schulze MB, Spranger J et al (2016) Obesity and type 2 diabetes in sub-Saharan Africans—is the burden in today’s Africa similar to African migrants in Europe? The RODAM study. BMC Med 14(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0709

Ammerman A, Corbie-Smith G, George DMM, Washington C, Weathers B, Jackson-Christian B (2003) Research expectations among African American church leaders in the PRAISE! project: a randomized trial guided by community-based participatory research. Am J Public Health 93(10):1720–1727. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.10.1720

Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J, Emery J, Farmer A, Griffiths F, Guthrie B, Lester H, Wilson P, Kinmonth AL (2007) Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ 334(7591):455–459. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39108.379965.BE

Corbie-Smith G, Ammerman AS, Katz ML, George DMM, Blumenthal C, Washington C, Weathers B, Keyserling TC, Switzer B (2003) Trust, benefit, satisfaction, and burden: a randomized controlled trial to reduce cancer risk through African-American churches. J Gen Intern Med 18(7):531–541. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.21061.x

Council MC (2022) Manchester’s plan to tackle obesity —Healthy Weight Strategy 2021.https://www.manchester.gov.uk/news/article/8791/manchesters_plan_to_tackle_obesity_-_healthy_weight_strateg. Accessed February 5, 2022

Edwards RW, Jumper-Thurman P, Plested BA, Oetting ER, Swanson L (2000) Community readiness: research to practice. J Commun Psychol 28(3):291–307. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(200005)28:3<291::AID-JCOP5>3.0.CO;2-9

Findholt N (2007) Application of the Community Readiness Model for childhood obesity prevention. Public Health Nurs 24(6). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00669.x

Gissing SC, Pradeilles R, Osei-Kwasi HA, Cohen E, Holdsworth M (2017) Drivers of dietary behaviours in women living in urban Africa: a systematic mapping review. Public Health Nutr 20(12):2104–2113. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017000970

Herbert J, Datta K, Evans Y, May J, McIlwaine C, Wills J (2006) Multiculturalism at work: the experiences of Ghanaians in London. Department of Geography, Queen Mary, University of London, London ISBN: 0-902238-39-8

Herbert J, May J, Wills J, Datta K, Evans Y, McIlwaine C (2008) Multicultural living? Experiences of everyday racism among Ghanaian migrants in London. Eur Urban Regional Stud 15(2):103–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776407087

Islam S, Small N, Bryant M, Yang T, De Chavez AC, Saville F, Dickerson J (2018) Addressing obesity in Roma communities: a community readiness approach. Int J Human Rights Healthcare 12(2):79–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHRH-06-2018-0038

Ismail SU, Asamane EA, Osei-Kwasi HA, Boateng D (2022) Socioeconomic determinants of cardiovascular diseases, obesity, and diabetes among migrants in the United Kingdom: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(5):3070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19053070

Kesten JM, Griffiths PL, Cameron N (2011) A systematic review to determine the effectiveness of interventions designed to prevent overweight and obesity in pre-adolescent girls. Obes Rev 12(12):997–1021. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00919.x

Kesten JM, Cameron N, Griffiths PL (2013) Assessing community readiness for overweight and obesity prevention in pre-adolescent girls: a case study. BMC Public Health 13(1):1–15 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/1205

Kesten JM, Griffiths PL, Cameron N (2015) A critical discussion of the Community Readiness Model using a case study of childhood obesity prevention in England. Health Soc Care Community 23(3):262–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12139

Koc M, Welsh J (2001) Food, foodways and immigrant experience. Centre for Studies in Food Security, Toronto. https://www.academia.edu/53150838/Food_Foodways_and_Immigrant_Experience. Accessed February 20, 2022

Landrine H, Klonoff EA (2004) Culture change and ethnic-minority health behavior: an operant theory of acculturation. J Behav Med 27(6):527–555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-004-0002-0

LifeConnect24 (2020) New obesity strategy: Is PM’s plan more harm than help? https://www.lifeline24.co.uk/obesity-strategy/. Accessed February 5, 2022

Marshall MN (1996) The key informant technique. Fam Pract 13:92–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/13.1.92

McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K (1988) An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 15(4):351–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818801500401

Marmot M (2020) Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on. The Health Foundation, London. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on. Accessed 16 October, 2022

Millar L, Robertson N, Allender S, Nichols M, Bennett C, Swinburn B (2013) Increasing community capacity and decreasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in a community based intervention among Australian adolescents. Prev Med 56(6):379–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.02.020

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2012) Obesity: working with local communities. Public health guideline [PH42]. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, London. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph42. Accessed March, 15, 2022

National Health Service (2022) Better health. National Health Service, London. https://www.nhs.uk/better-health/. Accessed March 16, 2022

Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF, Plested BA, Edwards RW, Kelly K, Beauvais F (1995) Assessing community readiness for prevention. Int J Addict 30(6):659–683. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826089509048752

Office for National Statistics (2014) UK population by country of birth and nationality: 2013. Office for National Statistics, Newport, Wales. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/migration1/population-by-country-of-birth-and-nationality/2013/index.html. Accessed January 5, 2022

Orozco M, Bump M, Fedewa R, Sienkiewicz K (2005) Diasporas, development and transnational integration: Ghanaians in the US, UK and Germany. Institute for the Study of International Migration and Inter-American Dialogue, Washington, DC. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Diasporas%2C+Development+and+Transnational+integration%3A+Ghanaians+in+the+US%2C+UK+and+Germany.&btnG=. Accessed 14 March, 2022

Osei-Kwasi HA, Nicolaou M, Powell K, Terragni L, Maes L, Stronks K, Lien N, & Holdsworth, M on behalf of the DEDIPAC consortium (2016) Systematic mapping review of the factors influencing dietary behaviour in ethnic minority groups living in Europe: a DEDIPAC study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, 13(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0412-8.

Osei-Kwasi HA, Nicolaou M, Powell K, Holdsworth M (2019) “I cannot sit here and eat alone when I know a fellow Ghanaian is suffering”: perceptions of food insecurity among Ghanaian migrants. Appetite 140:190–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.05.018

Osei-Kwasi HA, Powell K, Nicolaou M, Holdsworth M (2017) The influence of migration on dietary practices of Ghanaians living in the United Kingdom: a qualitative study. Ann Hum Biol 44(5):454–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/03014460.2017.1333148

Osei-Kwasi HA (2017) An exploration of dietary practices and associated factors amongst Ghanaians living in Europe. Doctoral dissertation, University of Sheffield

Plested BA, Jumper-Thurman P, Edwards RW (2016) Assessing community readiness for change. Increasing community capacity for HIV/AIDS prevention. Creating a climate that makes healthy change possible. Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO. http://www.oneskycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/CommunityReadinessManual_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 20 March, 2022

Poggie Jr (1972) Toward quality control in key informant data. Hum Organ 31(1):23–30. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44125113

Popkin BM (2004) The nutrition transition: an overview of world patterns of change. Nutr Rev 62(suppl_2):S140–S143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00084.x

Pradeilles R, Rousham EK, Norris SA, Kesten JM, Griffiths PL (2016) Community readiness for adolescents’ overweight and obesity prevention is low in urban South Africa: a case study. BMC Public Health 16(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3451-9

Pradeilles R, Marr C, Laar A, Holdsworth M, Zotor F, Tandoh Α, Klomegah S, Coleman N, Bash K, Green M, Griffiths PL (2019) How ready are communities to implement actions to improve diets of adolescent girls and women in urban Ghana? BMC Public Health 19(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6989-5

Pradeilles R, Holdsworth M, Olaitan O, Irache A, Osei-Kwasi HA, Ngandu CB, Cohen E (2022) Body size preferences for women and adolescent girls living in Africa: a mixed-methods systematic review. Public Health Nutr 25(3):738–759. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021000768

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC (1992) Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors. Prog Behav Modif 28:183–218 https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/psy_facpubs/53

Public Health England (2020) Tackling obesity: empowering adults and children to live healthier lives. Public Health England, London. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/tackling-obesity-government-strategy/tackling-obesity-empowering-adults-and-children-to-live-healthier-lives. Accessed 16, February, 2022

Public Health England (2021) Health priorities 2021. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID), London. https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/office-for-health-improvement-and-disparities/about%0Ahttps. Accessed March 16, 2022

Sliwa S, Goldberg JP, Clark V, Collins J, Edwards R, Hyatt RR, Bridgid Junot B, Nahar E, Nelson ME, Tovar A, Economos CD, (2011) Using the Community Readiness Model to select communities for a community-wide obesity prevention intervention. http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2011/nov/10_0267.htm. Accessed 16 March 2022

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the key informants who participated in this research, and AXA research fund for funding Dr Osei-Kwasi’s fellowship that resulted in the paper.

Funding

This paper is an output of Dr. Hibbah Araba Osei-Kwasi’s Research Fellowship, funded by AXA Research Fund. The content of the paper does not represent views of the funder.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HAO-K designed the study, collected the data, and wrote the first manuscript. HAO-K and RA processed and analysed the data. PJ, MH, ADA, RA, and PG reviewed the manuscript and made intellectual inputs. All authors read and endorsed the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The University of Sheffield Department of Geography Ethics Review Committee granted ethics approval to conduct the study.

Consent to participate

Consent was received from all study participants prior to recruitment and data collection, and they were informed that the findings will be written up and published in a widely read academic journal to benefit the public and other researchers.

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Osei-Kwasi, H.A., Jackson, P., Akparibo, R. et al. Assessing community readiness for overweight and obesity prevention among Ghanaian immigrants living in Greater Manchester, England. J Public Health (Berl.) 31, 1953–1967 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-022-01777-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-022-01777-1