Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to assess factors associated with the willingness to be vaccinated against hepatitis B among Indonesia’s adult population, considering cultural and geographic differences by analysing the two provinces of Aceh and Yogyakarta.

Subject and methods

An institution-based cross-sectional survey was conducted in 16 community health centres. A multivariable logistic regression model stratified by province was employed to assess variables associated with the willingness to receive hepatitis B vaccination.

Results

We found that participants from Yogyakarta more often had a higher knowledge and risk perception of hepatitis B and were more often willing to get vaccinated than participants from Aceh. We also found that a high-risk perception of hepatitis B infection was associated with the willingness to be vaccinated against hepatitis B in participants from both Aceh and Yogyakarta. Furthermore, in Yogyakarta, a fair and high knowledge of hepatitis B infection and vaccination, being female, and having health insurance covering hepatitis B vaccination costs were associated with the willingness to be vaccinated. In Aceh, health care workers in high-risk units for hepatitis B had a higher willingness to be vaccinated than those who were not high-risk health care workers.

Conclusion

Given the different factors associated with the willingness to be vaccinated against hepatitis B in Aceh and Yogyakarta, this study also highlights the need of a locally adjusted, culture-based approach to improve the hepatitis B vaccination programme.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Most people chronically infected with hepatitis B do not know that they are infected; thus, the infection goes unnoticed and undiagnosed until the virus has caused severe liver damage (WHO 2020a). In 2020, the World Health Organization reported that approximately 900,000 deaths are caused by hepatitis B virus infection annually (WHO 2020b). Indonesia is rated as an intermediate-to-high hepatitis B virus endemic region, and it is one of the 11 countries carrying almost 50% of the global burden of chronic hepatitis (WHO 2020a). The Indonesian Ministry of Health estimated that 7% of the population lives with hepatitis B, and approximately 20 million people were diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B in 2013 (The Indonesia Ministry of Health 2013). Moreover, hepatic cirrhosis was categorised as a catastrophic illness, with the seventh-highest expenditure of the Indonesian National Health Insurance between 2014 and 2017 (BPJS 2017).

Since 1997, a zero dose of hepatitis B for newborns, followed by three additional doses of hepatitis B for children has been implemented into Indonesia’s vaccination strategy (Purwono et al. 2016). However, hepatitis B vaccination coverage was overall low (less than 70% for each dose) with substantial differences between provinces (The Indonesia Ministry of Health 2018). In Yogyakarta, the coverage of hepatitis B vaccination was 97.8% for the first dose and 91% for each of three additional doses. While in Aceh, the coverage among newborns was only 53.9% for the first hepatitis B dose, followed by 26.9%, 24.9%, and 22.0% for three additional doses respectively (The Indonesia Ministry of Health 2018).

This difference may be due to the cultural and political situations in each province and the different histories. For example, Yogyakarta is a monarchy with an ancient sultanate (Harsono 2019), while Aceh is applying the Islamic Sharia Law which may have an indirect impact on the overall health program, including vaccination (Kholiq 2005; Syarkawi 2011; Harapan et al. 2021). Consequently, whereas in some countries, such as USA (Byrd et al. 2013) and Germany (Schenkel et al. 2008; Harder et al. 2013), hepatitis B vaccination is mandatory for health care personnel, many people in Indonesia, including high-risk populations such as health care workers, are unprotected from hepatitis B virus, especially in some provinces.

Although the Indonesian government published regulations about viral hepatitis prevention, recommending that the adult population and especially high-risk groups and people who have never received vaccinations should be vaccinated against hepatitis B (The Indonesia Ministry of Health 2015), currently, Indonesia does not have a compulsory hepatitis B vaccination programme for adults. Thus, people must actively decide to get immunized and bear the costs themselves. However, in order to reach the goals of the Global Hepatitis Elimination 2030 programme (WHO 2016), Indonesia is now preparing a new regulation of hepatitis B vaccination for adults. Starting in 2022, this program will first focus on voluntary vaccinations in health care workers (The Indonesia Ministry of Health 2020).

A study among nurses in Taiwan found that knowledge, the perceived benefit of immunisation, and the perceived barriers to it could predict the willingness to accept a hepatitis B vaccination (Chen et al. 2019). In China it was also found that socio-demographics, such as sex and education level, were the factors impacting the willingness to accept hepatitis B vaccination among migrant workers (Xiang et al. 2019). However, in Indonesia, data on knowledge of hepatitis B infection and vaccination and the community’s perception of both is limited.

Therefore, we investigated the willingness of Indonesia’s adult population to get vaccinated against hepatitis B in two Indonesian regions (Aceh and Yogyakarta). We determined associated variables, such as knowledge of hepatitis B infection and vaccination, its risk perception, as well as sociodemographic and other characteristics of the respondents. This is a first step in gauging the potential vaccine acceptance and will have large consequences for the upcoming vaccination program and economy (Neumann-Böhme et al. 2020; Yoda and Katsuyama 2021).

Materials and methods

Study design, study site, participants, and sampling procedure

An institution-based (community health centres, Indonesian “Puskesmas”), cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the factors associated with the willingness to accept hepatitis B vaccination among the adult population. In Indonesia, the public primary health care system is decentralized to the district level, with about more than 9,000 community health centres forming the backbone of the country’s health system (World Bank 2018). As a result, community health centres are considered to be a suitable setting in which to obtain a sample representing the population. This study was conducted from February to March 2020 at 16 community health centres in two provinces in Indonesia: Aceh and Yogyakarta. Both regions were selected because, according to the results of the Indonesian National Survey conducted in 2018, Yogyakarta Province had the highest vaccination coverage within the existing program (83.7% with complete vaccination, 16.3% with incomplete vaccination, and none without vaccination), while Aceh Province was reported to have the lowest coverage (19.5% with complete vaccination, 16.3% with incomplete vaccination, and 40.9% never vaccinated) (The Indonesia Ministry of Health 2013). This program is aimed at children aged 0 to 11 months and covers the first dose of hepatitis B, followed by three additional doses of hepatitis B, Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG), three doses of diphtheria–tetanus–pertussis, four doses of polio, as well as Haemophilus influenzae type B, and measles vaccination (The Indonesia Ministry of Health 2019).

Within the provinces, we selected two regions representing urban and rural areas. For the study purposes, the included urban area was defined as the province’s capital city, and the rural regions were randomly selected from the district list in each province. Consequently, we included the cities of Banda Aceh and Yogyakarta as the urban areas and the districts of Takengon and Gunungkidul as rural areas. Data were collected from four health centres that were randomly selected from the health centre list in each city/district. Only health centres that were accredited by the local health office were included in this study.

Health care workers and outpatients were included in this study. A health care worker was defined as a person who works in a health centre with both medical and non-medical backgrounds, such as medical doctors, dentists, nurses, midwives, analysts, pharmacy, helpers, administrative personnel, drivers, cleaners, and security personnel. An outpatient was a person who was registered as an outpatient at the health centre on the same day that the data were collected. Thereby, outpatients working in other health care centres could later be classified as health care workers. To be included in the study, a participant had to meet the following criteria: older than 15 years of age, in good physical condition, able to answer the questions, willing to participate in the study, and never received hepatitis B vaccination as adults before. Participant who have been infected with hepatitis B or who were already vaccinated against hepatitis B were excluded from this study.

The health care workers were selected through simple random sampling from the centres’ employment data. The outpatients were chosen through systematic random sampling, in which the sampling interval referred to the average number of visitors (outpatients) daily in each health centre. At health centres with a small number of health care workers and visitors of outpatients per day, we included all health care workers and outpatients that were eligible and willing to participate during the data collection day. Data collection was achieved through face-to-face interviews conducted by the interviewer. We involved two local enumerators, who were trained and supervised by one field coordinator. The collected data were double-checked by the field coordinator and the principal investigator.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was based on previous studies (Aaron et al. 2017; Abeje and Azage 2015; Abiodun et al. 2019; Abiye et al. 2019; Ahmad et al. 2016; Akibu et al. 2018; Chao et al. 2010; Pathoumthong et al. 2014; Rajamoorthy et al. 2019) and translated into Bahasa. A pre-test was conducted with 33 participants (health care workers and outpatients) in one of the health centres in West Java, and necessary modification was done after the pre-test. We also improved the data collection technique based on this experience. A structured questionnaire included 15 questions about socio-demographic information, 44 questions about knowledge and risk perception regarding hepatitis B infection, and five questions about the willingness to be vaccinated and pay for hepatitis B vaccination (see supplement 1).

Variables

This study’s outcome was the willingness to accept hepatitis B vaccination (“Are you willing to accept a hepatitis B vaccination for adults?”). The socio-demographic variables included in the study were age group (35 to 50 versus (vs) > 50 vs < 35 years old), sex (women vs men), marital status (married vs single/widowed/divorced), religion (Moslem vs Christian and others), residency (urban vs rural), education (secondary and higher education vs primary education), occupational status (employed vs unemployed), profession within the health centre (non health care worker vs high-risk vs low-risk health care worker), monthly income (middle–upper, and upper/high monthly-income vs low monthly-income), and having a health insurance covering hepatitis B vaccination costs (no vs yes). We also considered variables related to exposure to information on hepatitis B: having heard of hepatitis B and knowing someone infected with hepatitis B. In addition, we assessed knowledge of hepatitis B infection and vaccination and risk perceptions of hepatitis B infection. Twenty-nine questions were used to measure knowledge of hepatitis B infection and vaccination. Possible responses to the knowledge questions were “true”, “false”, and “do not know”. Fifteen questions were used to measure the level of risk perception regarding hepatitis B infection. There were two response options for the risk perception questions — “agree” and “disagree” — which measured the extent to which participants believed they could potentially be infected with hepatitis B. A correct answer of knowledge and an agreeing response regarding risk of hepatitis B infection and vaccination was given a score of one; an incorrect answer of knowledge and a disagreeing response of risk perception regarding hepatitis B infection was assigned a score of zero. Consequently, each subject had a total sum of correct and positive answers (see supplements 2 and 3). The total score of knowledge was divided into three categories: poor knowledge (less than 50% correct answers), fair knowledge (50% to 75% correct answers), and good knowledge (more than 75% correct answers). The risk perception was categorised into two groups based on the median cut-off point: low-risk perception and high-risk perception.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 20 was used for the data analysis. Descriptive analysis ascertained the frequencies of the data, presented as percentages for the categorical variables. We built a multivariable logistic regression to analyse factors associated with the willingness to accept hepatitis B vaccination. First, all independent variables that were associated with the outcome variable based on previous studies were included into univariable logistic regression analyses. This resulted in crude odds ratios of model 1 in Table 4 (Harapan et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2019; Xiang et al. 2019; Yoda and Katsuyama 2021; Abeje and Azage 2015; Abiodun et al. 2019; Abiye et al. 2019; Pathoumthong et al. 2014; Rajamoorthy et al. 2019; Eilers et al. 2014; Park et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2016; Ghomraoui et al. 2016; Machmud et al. 2021). Then, all variables were included in a multivariable logistic regression model resulting in adjusted odds ratios of model 2 (Table 4). For odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown. Economic status was not included in this analysis, because more than 80% of the data were missing. Since all participants of the variable “Christian and others” answered that they were willing to accept hepatitis B vaccination (thereby presenting a cell in the data table with the value zero), the odds ratios were obtained from standard contingency table analysis using Haldane's modification of Woolf's method (Ruxton and Neuhäuser 2013) and statistical significance was assessed by a two-tailed Fisher’s exact test.

Ethics approval

The Research and Community Engagement Ethical Committee, the Faculty of Public Health, University Indonesia (196/UN2.F10.D11/PPM.00.02/2020), and the ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Martin Luther University Halle–Wittenberg (processing number: 2021-140), approved the study protocol. All participants signed written informed consent forms prior to enrolment. The work was carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for studies that involve humans.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

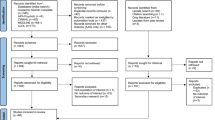

In this study, a total of 1000 participants were approached, of whom 98 refused to participate, seven started and refused to continue the interview, and 138 were excluded due to vaccination or infection with hepatitis B before, leaving a dataset with a total of 757 (84.6%) participants: 373 (49.3%) from Aceh and 384 (50.7%) from Yogyakarta (Fig. 1). Differences in socio-demographic variables between provinces were observed for age group, sex, religion, education level, profession, and health insurance (Table 1). Compared to participants from Yogyakarta, participants from Aceh were more often older than 35 years of age, women, Moslem, more often had a higher education level, and a profession as health care worker; they less often had insurance covering hepatitis B vaccination.

Exposure to information on hepatitis B

In both Aceh and Yogyakarta, around 50% of participants claimed that they had heard information on hepatitis B vaccination for adults. Most of them had heard information on hepatitis B from their health provider, followed by the media. Among the participants who had heard information on hepatitis B information in the media, most used television and social media as the platform to obtain that information (Table 2).

Knowledge and risk perception of hepatitis B and willingness to be vaccinated

Participants from Yogyakarta more often had good knowledge about hepatitis B infection (20.8% vs 8.6% in Aceh, Table 3), vaccination (17.2% vs 12.1% in Aceh) and high risk perceptions of hepatitis B infection (57.8% vs 42.6% in Aceh). In Yogyakarta, they were also more often willing to be vaccinated against hepatitis B (88% vs 81% in Aceh).

Variables associated with the willingness to be vaccinated against hepatitis B

The association between each independent variable and the likelihood of the willingness to take the vaccine was investigated. Crude odds ratios are presented in model 1 (Table 4).

After adjustment, risk perception of hepatitis B was the only variable positively associated with the willingness to accept a hepatitis B vaccination in both provinces. Thereby, the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) for respondents who, based on our questionnaire (see supplement 1), were considered to have a high-risk perception compared to those considered to have a low-risk perception was almost double in Yogyakarta (AOR 5.11; 95% CI: 2.29–11.41, Table 4) compared to Aceh (AOR 2.58; 95% CI: 1.34–4.98).

In Yogyakarta, but not in Aceh, participants with fair and good knowledge of hepatitis B infection and vaccination were 5 times more likely to be willing to get vaccinated against hepatitis B than participants with poor knowledge (AOR 2.48; 95% CI: 1.01–6.14 and AOR 4.77; 95% CI: 1.04–21.83 for fair and good knowledge, respectively). Women in Yogyakarta also had higher odds for the willingness to be vaccinated (AOR 3.92; 95% CI: 1.93–7.96) than men, but not in Aceh. Furthermore, only participants from Yogyakarta with insurance covering vaccination costs were almost 5 times more likely to accept a hepatitis B vaccination compared to those without that kind of insurance (AOR 4.80; 95% CI: 1.01–22.78).

In contrast, only participants from Aceh working as health care workers in hepatitis B high-risk units were 4 times more likely to accept hepatitis B vaccination compared to non health care workers (AOR 4.07; 95% CI: 1.99–8.33). There were no associations in either province between age, residency, marital status, education level, occupational status, heaving heard about hepatitis B, and knowing someone infected with hepatitis B.

Discussion

We investigated the willingness of Indonesia’s adult population to get vaccinated against hepatitis B in two provinces, Aceh and Yogyakarta. Furthermore, we assessed factors associated with the willingness to accept hepatitis B vaccination as a first step in measuring the potential vaccine acceptance among the adult population in Indonesia.

In total, 84.5% of participants were willing to accept hepatitis B vaccination. This result may reflect the fact that most participants understood the benefits of hepatitis B vaccination. In contrast, a previous study in China found that only 30.3% of unvaccinated adults said hepatitis B vaccination was needed (Yu et al. 2016). This difference may be due to the fact that 50.2% of our population are health workers. We also found that 7% more participants from Yogyakarta were willing to accept a hepatitis B vaccination than from Aceh. This may result in a large effect when applied to a population such as Indonesia’s (World Bank 2021). Yogyakarta, located in Central Java, and Aceh in the western-most part of Indonesia each have their own decentralized health programmes (BPS 2020b; Nasution 2016). Furthermore, Yogyakarta is one of the provinces in Indonesia with a monarchy system (the kingdom Sultanate of Yogyakarta) (Harsono 2019). It is one of the provinces with a Javanese culture, which is famous for its high harmony, character of self-control, peace, and tolerance (Nashori et al. 2020) and one of the most popular places for education and tourism in Indonesia, with a multi-ethnic population (BPS 2020a). All the above may have valuable impact on the health program including vaccination. Therefore, it is not surprising we found people from Yogyakarta to be more amenable to new ideas or policies, including health programmes.

The common factor associated with a high willingness to get vaccinated against hepatitis B, in Yogyakarta and Aceh, was a high-risk perception of hepatitis B infection. Thereby, the awareness of risk may be associated with a person’s motivation to be vaccinated (Xiang et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2019). A systematic review among immigrants and refugees concluded that health decision-making, such as vaccination, is also influenced by attitude and risk perception (Owiti et al. 2015). Eilers et al. also found that people’s attitudes and beliefs regarding immunisation are the most critical factors of vaccine uptake in western societies (Eilers et al. 2014). Moreover, several studies found that one reason for participants not wanting to be vaccinated was that they never felt the need for it or were unaware of it (Park et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2016; Ibrahim and Idris 2014; Ghomraoui et al. 2016; Khandelwal et al. 2017; Machmud et al. 2021). Risk perception is also related to several factors such as education, information exposure, knowledge, and experience of exposure. For example, Mullins et al. found that as knowledge increased over time, risk perception often became more accurate (Mullins et al. 2015).

We also found different factors associated with the willingness to be vaccinated in the different regions, i.e., higher knowledge of hepatitis B infection and vaccination, being female, and having insurance covering hepatitis B vaccination in Yogyakarta and being a high-risk health care worker in Aceh. In Yogyakarta, the influence of the sultanate tradition fully supports the empowerment of women, and encourages women to make independent choices such as health action decisions (Ratnawati and Santoso 2021).

Furthermore, the provincial minimum wage is lower in Yogyakarta than in Aceh (approximately, Rp.1.700.000 vs Rp.3.100.000 or 117 USD vs 213 USD per month in 2021) (Yogyakarta Government 2020). The cost of the adult vaccination in Indonesia reached Rp.255.000 (16.34 USD) per dose (St. Carolus Hospital 2020), which is around 14% of the minimum monthly income in Yogyakarta and 8% of the minimum monthly income in Aceh per dose. Therefore, the coverage of vaccination costs by insurance has a larger effect in Yogyakarta than in Aceh. Furthermore, the inability to afford vaccination is a common reason for adult populations to choose not to be vaccinated (Akibu et al. 2018; Pathoumthong et al. 2014; Yuan et al. 2019; Tatsilong et al. 2016; Noubiap et al. 2013, 2014; Vo et al. 2018; Osei et al. 2019; Omotowo et al. 2018; Park et al. 2012).

As opposed to Yogyakarta, in Aceh, which has a strong history as the first area of the entry of Islam in Indonesia resulting in autonomy (Kholiq 2005) and the official implementation of Islamic Sharia Law (Kholiq 2005; Syarkawi 2011), knowledge of hepatitis B infection and vaccination may not affect someone in their willingness to be vaccinated. This may be due to a controversy of a forbidden ingredient in the vaccine opposing religious rules (the vaccine not being halal) (Harapan et al. 2021). For this reason, in Aceh, people may feel unconfident with regard to vaccination although they know about the benefit of vaccination. A possible motivation for high-risk health care workers in Aceh to be willing to get vaccinated may be self-protection (Adeyemi et al. 2013; Chung et al. 2012; Ochu and Beynon 2017).

Due to small numbers of non-Muslim participants, our analysis can only show a tendency of the association between religion and willingness to be vaccinated. In the literature, there are different reports on this relationship. Several studies show that religious law influences vaccination coverage, i.e., a study by Azizi et al. from Indonesia’s neighbour country Malaysia (Harapan et al. 2021; Basharat and Shaikh 2017; Syiroj et al. 2019; Azizi et al. 2017). However, some studies did not find an association between religion and vaccination at all (Osei et al. 2019; Shao et al. 2018). Therefore, further research in this field is needed and could assist strategic planning of vaccination programmes, especially in Muslim-majority countries.

Overall, we can see large differences regarding knowledge and risk perception between the provinces in our data. Thus, we believe that vaccine strategies have to be adapted based on local needs, and they should use culturally appropriate approaches for vaccination programmes since there may be no one-size-fits-all solution for all regions (Hardt et al. 2016; Frew et al. 2014). However, there are grounds for believing that increasing the risk perception of hepatitis B in the general population and adjusting measurements to local religion and culture could have a positive effect in a common Indonesian health programme.

To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to identify predictive factors of the willingness to accept hepatitis B vaccination involving two regions with different degrees of vaccination coverage in their vaccination programmes. However, this study also has some limitations. Selection bias is one of the limitations. Most of the visitors in the included health centres were women, which might be sufficient to reduce the ability to generalise the study’s results. Additionally, some studies have shown that economic factors were one of the factors that had a significant impact on vaccination status (Chung et al. 2012; Park et al. 2013; Park et al. 2012), but that was not included in this study due to a high amount of missing data. This study could also not show a difference between religions because most of the participants were Muslims (95.9%). Lastly, the participants might have provided favourable answers during the interview as a form of social desirability bias. Despite these limitations, this study’s results are considered to significantly contribute to public health knowledge.

Conclusions

This study found differences in knowledge, risk perception, and the willingness to be vaccination between the Indonesian provinces Yogyakarta and Aceh. Risk perception of hepatitis B infection impacts the willingness to be vaccinated in both provinces, which could provide ground for consideration in a common health care programme. However, other factors are also associated to the willingness to be vaccinated in Aceh and Yogyakarta. Our study shows that cost of hepatitis B is one of the main reasons for not getting vaccinated in Yogyakarta; as a result, the general health insurance could cover costs of hepatitis B vaccination. Furthermore, we identified that a local, culture-based approach may be needed for a successful vaccination programme. Therefore, further studies are necessary to identify the best cultural and local-based approaches, also considering religious rules.

Availability of data and material

The dataset generated and/or analysed during the current study is not publicly available due to the fact that it constitutes an excerpt of research in progress, but is available from the first author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable

References

Aaron D, Nagu TJ, Rwegasha J, Komba E (2017) Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among healthcare workers at national hospital in Tanzania: how much, who and why? BMC Infect Dis 17:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2893-8

Abeje G, Azage M (2015) Hepatitis B vaccine knowledge and vaccination status among health care workers of Bahir Dar City Administration, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 15:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-0756-8

Abiodun O, Shobowale O, Elikwu C, Ogbaro D, Omotosho A, Mark B, Akinbole A (2019) Risk perception and knowledge of hepatitis B infection among cleaners in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 7:11–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2017.12.001

Abiye S, Yitayal M, Abere G, Adimasu A (2019) Health professionals’ acceptance and willingness to pay for hepatitis B virus vaccination in Gondar City Administration governmental health institutions, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res 19:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4671-3

Adeyemi AB, Enabor OO, Ugwu IA, Bello FA, Olayemi OO (2013) Knowledge of hepatitis B virus infection, access to screening and vaccination among pregnant women in Ibadan, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol 33:155–159. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2012.711389

Ahmad A, Munn Sann L, Abdul Rahman H (2016) Factors associated with knowledge, attitude and practice related to hepatitis B and C among international students of Universiti Putra Malaysia. BMC Public Health 16:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3188-5

Akibu M, Nurgi S, Tadese M, Tsega WD (2018) Attitude and vaccination status of healthcare workers against Hepatitis B Infection in a teaching hospital, Ethiopia. Scientifica 2018:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6705305

Azizi FSM, Kew Y, Moy FM (2017) Vaccine hesitancy among parents in multi-ethnic country, Malaysia. Vaccine 35:2955–2961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.010

Basharat S, Shaikh BT (2017) Polio immunization in Pakistan: ethical issues and challenges. Public Health Rev 38:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0049-4

BPS (Statistics Indonesia) (2020a) Kota Yogyakarta dalam angka 2020. BPS-Statistics of Yogyakarta Municipality, Yogyakarta

BPS (Statistics Indonesia) (2020b) Statistical yearbook of Indonesia. BPS-Statistics Indonesia, Jakarta

Byrd KK, Lu PJ, Murphy TV (2013) Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among health-care personnel in the United States. Public Health Rep 128:498–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491312800609

Chao J, Chang ET, So SK (2010) Hepatitis B and liver cancer knowledge and practices among healthcare and public health professionals in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 10:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-98

Chen I, Master SH, Wu JJ, Master YW, Lin Y, Chung M, Huang P, Miao N (2019) Determinants of nurses’ willingness to receive vaccines: application of the health belief model. J Clin Nurs 28:3430–3440. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14934

Chung PW, Suen SH, Chan OK, Lao TH, Leung TY (2012) Awareness and knowledge of hepatitis B infection and prevention and the use of hepatitis B vaccination in the Hong Kong adult Chinese population. Chin Med J 125:422–427. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2012.03.004

Eilers R, Krabbe PFM, de Melker HE (2014) Factors affecting the uptake of vaccination by the elderly in Western society. Prev Med 69:224–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.10.017

Frew PM, Alhanti B, Vo-Green L, Zhang S, Liu C, Nguyen T, Schamel J, Saint-Victor DS, Nguyen ML (2014) Multilevel factors influencing hepatitis B screening and vaccination among Vietnamese Americans in Atlanta, Georgia. Yale J Biol Med 87:455–471

Ghomraoui FA, Alfaqeeh FA, Algadheeb AS, Al-Alsheikh AS, Al-Hamoudi WK, Alswat KA (2016) Medical students' awareness of and compliance with the hepatitis B vaccine in a tertiary care academic hospital: an epidemiological study. J Infect Public Health 9:60–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2015.06.008

Harapan H, Shields N, Kachoria AG, Shotwell A, Wagner AL (2021) Religion and measles vaccination in Indonesia, 1991–2017. Am J Prev Med 60:44–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.07.029

Harder T, Remschmidt C, Falkenhorst G, Zimmermann R, Hengel H, Ledig T, Oppermann H, Zeuzem S, Wicker S (2013) Background paper to the revised recommendation for hepatitis B vaccination of persons at particular risk and for hepatitis B postexposure prophylaxis in Germany. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz 11:1565–1576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-013-1845-8

Hardt K, Bonanni P, King S, Santos JI, El-Hodhod M, Zimet GD, Preiss S (2016) Vaccine strategies: optimising outcomes. Vaccine 34:6691–6699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.078

Harsono D (2019) A monarchy without a kingdom: Yogyakarta's exceptional system of government. Dissertation, La Trobe University, Melbourne

Hospital SC (2020) Adult vaccination and promotion. St. Carolus Hospital, Jakarta

Ibrahim N, Idris A (2014) Hepatitis B awareness among medical students and their vaccination status at Syrian Private University. Hepatitis Res Treat 2014:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/131920

Khandelwal V, Khandelwal S, Gupta N, Nayak UA, Kulshreshtha N, Baliga S (2017) Knowledge of hepatitis B virus infection and its control practices among dental students in an Indian city. Int J Adolesc Med Health 30(5):/j/ijamh.2018.30.issue-5/ijamh-2016-0103/ijamh-2016-0103.xml. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2016-0103

Kholiq MA (2005) Pemberlakuan Syari’at islam di Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam (NAD). Jurnal Hukum 12:60–75

Machmud PB, Glasauer S, Gottschick C, Mikolajczyk R (2021) Knowledge, vaccination status, and reasons for avoiding vaccinations against Hepatitis B in developing countries: a systematic review. Vaccines 9:1–26. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9060625

Mullins TLK, Widdice LE, Rosenthal SL, Zimet GD, Kahna JA (2015) Risk perceptions, sexual attitudes, and sexual behavior after HPV vaccination in 11–12 year-old girls. Vaccine 33:3907–3912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.060

Nashori F, Iskandar TZ, Setiono K, Siswadi AGP, Andriansyah Y (2020) Religiosity, interpersonal attachment, and forgiveness among the Javanese population in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Ment Health Relig Cult 23:99–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2019.1646233

Nasution A (2016) Government Decentralization Program in Indonesia. ADBI working paper series. Asian Development Bank Institute, Japan

Neumann-Böhme S, Varghese NE, Sabat I, Barros PP, Brouwer W, van Exel J, Schreyögg J, Stargardt T (2020) Once we have it, will we use it? A European survey on willingness to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Eur J Health Econ 21:977–982. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-020-01208-6

Noubiap JJ, Nansseu JRN, Kengne KK, Ndoula ST, Agyingi LA (2013) Occupational exposure to blood, hepatitis B vaccine knowledge and uptake among medical students in Cameroon. BMC Med Educ 13:148. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-148

Noubiap JJ, Nansseu JRN, Kengne KK, Wonkam A, Wiysonge CS (2014) Low hepatitis B vaccine uptake among surgical residents in Cameroon. Int Arch Med 7:11–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1755-7682-7-11

Ochu CL, Beynon CM (2017) Hepatitis B vaccination coverage, knowledge and sociodemographic determinants of uptake in high risk public safety workers in Kaduna State, Nigeria: a cross sectional survey. BMJ Open 7:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015845

Omotowo IB, Meka IA, Ijoma UN, Okoli VE, Obienu O, Nwagha T, Ndu AC, Onodugo OO, Onyekonwu LC, Ugwu EO (2018) Uptake of hepatitis B vaccination and its determinants among health care workers in a tertiary health facility in Enugu, South-East Nigeria. BMC Infect Dis 18:288. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3191-9

Osei E, Niyilapah J, Amenuvegbe GK (2019) Hepatitis B knowledge, testing, and vaccination history among undergraduate public health students in Ghana. Biomed Res Int 2019:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7645106

Owiti JA, Greenhalgh T, Sweeney L, Foster GR, Bhui KS (2015) Illness perception and explanatory models of viral hepatitis B and C among immigrants and refugees: a narrative systematic review. BMC Public Health 15:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1476-0

Park B, Choi KS, Lee H, Jun JK, Park E (2012) Socioeconomic inequalities in completion of hepatitis B vaccine series among Korean women: results from a nationwide interview survey. Vaccine 30:5844–5848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.022

Park B, Choi KS, Lee H, Kwak M, Jun JK, Park E (2013) Determinants of suboptimal hepatitis B vaccine uptake among men in the Republic of Korea: where should our efforts be focused: results from cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 13:218–218. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-218

Pathoumthong K, Khampanisong P, Quet F, Latthaphasavang V, Souvong V, Buisson Y (2014) Vaccination status, knowledge and awareness towards hepatitis B among students of health professions in Vientiane, Lao PDR. Vaccine 32:4993–4999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.07.022

Purwono PB, Juniastuti, Amin M, Bramanthi R, Nursidah REM, Wahyuni RM, Yano Y, Hotta H, Hayashi Y, Utsumi T, Lusida MI (2016)Hepatitis B virus infection in Indonesia 15 years after adoption of a universal infant vaccination program: possible impacts of low birth dose coverage and a vaccine-escape mutant. Am J Trop Med Hyg 95:674–679. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.15-0121

Rajamoorthy Y, Taib NM, Munusamy S, Anwar S, Wagner AL, Mudatsir M, Müller R, Kuch U, Groneberg DA, Harapan H, Khin AA (2019) Knowledge and awareness of hepatitis B among households in Malaysia: a community-based cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 19:47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6375-8

Ratnawati, Santoso P (2021) Gender politics of Sultan Hamengkubuwono x in the succession of Yogyakarta Palace. Cogent Social Sciences 7:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1976966

Ruxton GD, Neuhäuser M (2013) Review of alternative approaches to calculation of a confidence interval for the odds ratio of a 2 3 2 contingency table. British Ecol Soc 4:9–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00250.x

Schenkel K, Radun D, Bremer V, Bocter N, Hamouda O (2008) Viral hepatitis in Germany: poor vaccination coverage and little knowledge about transmission in target groups. BMC Public Health 8:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-132

Shao ER, Mboya IB, Gunda DW, Ruhangisa FG, Temu EM, Nkwama ML, Pyuza JJ, Kilonzo KG, Lyamuya FS, Maro VP (2018) Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and associated factors among healthcare workers in northern Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis 18:474. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3376-2

Syarkawi (2011) Revitalisasi adat istiadat dan pembentukan karakter: Analisis terhadap adat istiadat dan pembentukan karakter Syari’at di Aceh. Lentera 11:40–51

Syiroj AT, Pardosi JF, Heywood AE (2019) Exploring parents’ reasons for incomplete childhood immunisation in Indonesia. Vaccine 37:6486–6493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.08.081

Tatsilong HOP, Noubiap JJN, Nansseu JRN, Aminde LN, Bigna JJR, Ndze VN, Moyou RS (2016) Hepatitis B infection awareness, vaccine perceptions and uptake, and serological profile of a group of health care workers in Yaoundé, Cameroon. BMC Public Health 15:706–706. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3388-z

The Indonesia Ministry of Health (2013) Indonesia National Health Survey Report 2013. The Indonesia Ministry of Health, Jakarta, Indonesia

The Indonesia Ministry of Health (2015) Regulation of hepatitis virus prevention in Indonesia no. 53/2015. The Indonesian Ministry of Health, Jakarta, Indonesia

The Indonesia Ministry of Health (2018) Indonesia National Health Survey Report 2018. The Indonesia Ministry of Health, Jakarta, Indonesia

The Indonesia Ministry of Health (2019) Program imunisasi ibu hamil, bayi dan batita di Indonesia. The Indonesia Ministry of Health, Jakarta, Indonesia

The Indonesia Ministry of Health (2020) National Action Plan of Hepatitis 2020 to 2024. MoH, Indonesia

The Indonesian National Health Insurance System (BPJS) (2017) Laporan pegelolaan program dan laporan keuangan jaminan sosial kesehatan tahun 2017. The Indonesian National Health Insurance System (BPJS), Jakarta

Vo TQ, Nguyen TLH, Pham MN (2018) Exploring knowledge and attitudes toward the hepatitis B virus: an internet-based study among Vietnamese healthcare students. J Pharm Pharmacogn Res 6:458–470

World Bank (2018) Is Indonesia ready to serve? An analysis of Indonesia’s primary health care supply-side readliness. World Bank, Jakarta

World Bank (2021) Data of population: Indonesia. World Bank, Jakarta

World Health Organization (WHO) (2016) Combating Hepatitis B and C to reach elimination by 2030 (Advocacy Brief). WHO, Villars-sous-Yens, Switzerland

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020a) Hepatitis B. WHO, Geneva

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020b) Toward the elimination of Hepatitis B and C 2030. WHO, Geneva

Xiang H, Tang X, Xiao M, Gan L, Chu K, Li S, Tian Y, Lei X (2019) Study on status and willingness towards hepatitis B vaccination among migrant workers in Chongqing, China: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16:1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16204046

Yoda T, Katsuyama H (2021) Willingness to receive COVID-19 vaccination in Japan. Vaccines 9:1–8. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9010048

Yogyakarta Government (2020) Sri Sultan tetapkan UMP DIY 2021 naik 3.54%. Yogyakarta Government, Yogyakarta

Yu L, Wang J, Wangen KR, Chen R, Maitland E, Nicholas S (2016) Factors associated with adults' perceived need to vaccinate against hepatitis B in rural China. Hum Vaccin Immunother 12:1149–1154. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2015.1132964

Yuan Q, Wang F, Zheng H, Zhang G, Miao N, Sun X, Woodring J, Chan P, Cui F (2019) Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among health care workers in China. PLoS One 14:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216598

Acknowledgment

The author (PBM) greatly appreciates the support (scholarship) from the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP). The authors are grateful to the health offices of Banda Aceh, Aceh Tengah, Yogyakarta, and Gunungkidul for allowing us to collect data in the selected health centres

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Partial financial support was received from the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) and open access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.B.M. investigated, analysed the data, and wrote the original draft. C.G. and R.M. validated and supervised. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Research and Community Engagement Ethical Committee, the Faculty of Public Health, University Indonesia (196/UN2.F10.D11/PPM.00.02/2020), and the ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Martin Luther University Halle–Wittenberg (processing number: 2021-140). Informed consent forms and authorization forms were obtained from each eligible participant who volunteered to participate in the study.

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

ESM 1

(DOCX 138 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Machmud, P.B., Mikolajczyk, R. & Gottschick, C. Understanding hepatitis B vaccination willingness in the adult population in Indonesia: a survey among outpatient and healthcare workers in community health centers. J Public Health (Berl.) 31, 1969–1980 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-022-01775-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-022-01775-3