Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to analyse the number of deceased people who received different types of outpatient palliative care, the length of time prior to death that care was initiated, and their palliative care trajectory including the rate of hospital death.

Subject and methods

Data on 35,514 adults insured by the statutory health insurance who died in 2017 in Lower Saxony, Germany, were analysed. The study examined the provision of three different types of outpatient palliative care: general (GPC), intermediate (IPC) and specialised palliative care (SPC). In addition, oncological palliative care services (OS) were considered. Descriptive analyses include frequencies, timing and duration of these services, the number of inpatient hospital stays and hospital deaths.

Results

Prior to death, 31.4% of the deceased received outpatient palliative care: 21.3% GPC, 6.4% GPC with IPC and/or SPC and/or OS; and 3.7% IPC and/or SPC and/or OS, but no GPC. On average, GPC and OS were initiated 9 months and SPC 3 months prior to death. Six percent of the analytic sample received outpatient palliative care more than 2 years before death. Compared to those without outpatient palliative care, patients who received outpatient palliative care had more and longer inpatient hospital stays, but less frequently died in hospital.

Conclusion

Early outpatient palliative care took place in a minor percentage of deceased. Outpatient palliative care starts late before death for most patients, but enables more people not to die in hospital. However, significantly fewer people receive outpatient palliative care relative to current demand estimates. This is particularly true of general outpatient palliative care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to sociodemographic changes, the number of old and very old people is rising worldwide. In Germany, the absolute number of residents aged 80 years and older is expected to reach 10.5 million in 2050 (Statistisches Bundesamt 2019). This increase in the aged population will likely be accompanied by increased morbidity and rising healthcare costs (de Meijer et al. 2013).

Analyses have indicated that approximately 80% of people require palliative care before death. However, the precise figure varies as a function of age, with 40.7% of 30–39-year-olds requiring palliative care and 96.1% of those aged 80+ years (Scholten et al. 2016). In Germany, outpatient palliative care is differentiated into general and specialised palliative care. General outpatient palliative care (GPC) is the foundation of all palliative care approaches, and it is primarily administered by general practitioners (GPs), who do not require specific palliative care training for this purpose. GPC is specifically intended to treat patients suffering from chronic progressive diseases with low to medium symptom complexity (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin 2013). In contrast, the indication for specialised outpatient palliative care (SPC) is greater symptom complexity and patient care needs; an estimated 10–20% of people with incurable, progressive oncological and non-oncological diseases meet these criteria (Melching 2015; Bausewein et al. 2015). SPC is also applied by GPs, but requires specific training in PC.

In recent years, extensive political and social legislative measures have been taken to expand and strengthen outpatient palliative care in Germany. The key features of these measures include (i) the right for every patient to receive SPC (Spezialisierte Ambulante Palliatvversorgung 2019), (ii) an extended GPC reimbursement system (in 2013) (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin 2020; Institut des Bewertungsausschusses 2013) and (iii) the integration of a third type of intermediate outpatient palliative care in 2017 (Bundesmantelvertrag-Ärzte 2016). The intermediate outpatient palliative care (IPC) represents an in-between stage of palliative care for outpatients for whom SPC is not (yet) or no longer indicated, due to a lack of a complex symptom trajectory, but who nevertheless present increased care needs that cannot be met by GPC (Bundesmantelvertrag-Ärzte 2016). In addition, patients with a cancer disease have access to special oncological palliative care services (OS), which provides a fourth approach to outpatient palliative care (Bundesmantelvertrag-Ärzte 2009) delivered by oncologists.

The shared goals of these four outpatient palliative care approaches (i.e. GPC, IPC, SPC, OS) are improved quality of life, sufficient symptom control (as subjectively perceived by the patient), prevention of (unwanted) hospital stays, and allowing death to occur in the home environment (Bausewein et al. 2015; Hui et al. 2014; Radbruch et al. 2019).

Study aim

The present research aimed at analysing health insurance data to determine (i) the four different types and time points/duration of outpatient palliative care administered to insured people in the federal state of Lower Saxony who died in 2017; (ii) the relations between outpatient palliative care services, inpatient hospital stays and place of death; and (iii) a comparison between the actual services administered and the estimated demand for outpatient palliative care.

Material and methods

Study design

The study involved a retrospective secondary analysis of the routine data of the statutory health insurance company AOK Lower Saxony (AOK Niedersachsen; AOKN), relating to insured persons who died in 2017. With 2.9 million insured persons, the AOKN has a market share of 36% in this region (AOK Niedersachsen 2021). Lower Saxony is one of 16 federal states in Germany with a total population of more than 7.9 million residents and a population density of 167 residents per km2, which is slightly less than the German average with 232 per km2 (Statistikportal 2018).

Study population and group formation

Initially, 36,855 data sets of people who died in 2017 were exported. Individuals were included if they were at least 18 years old at the time of death and if they were continuously insured with the AOKN in a pre-observation period from 2014 until death (see Fig. 1). If these criteria were not met, they had to be excluded. Following this, a cohort of 35,514 was created for the present evaluation. They represented 96.4% of all people insured by the AOKN who died in 2017 and form the study sample for the following analyses.

The cohort was analysed with respect to the different forms of outpatient palliative care (GPC, SPC, IPC, OS) that individuals received prior to death, according to the billing codes from the remuneration system for outpatient medical care in Germany (EBM: uniform value scale) indicated by physicians (see Table 1).

Focusing on GPC delivered by GPs, the following four subgroups were formed for the analyses: (i) persons who received only GPC (group 1), (ii) persons who received GPC and other outpatient palliative services (SPC and/or IPC and/or OS) (group 2), (iii) persons who received no GPC but did receive other outpatient palliative services (group 3) and (iv) persons who received no outpatient palliative care (group 4) (see Fig. 1).

The IPC was not included in the EBM until the fourth quarter of 2017; therefore, it was only indicated for a subgroup of the cohort during a very short interval prior to death. For this reason, it was categorised as an ‘other outpatient palliative service’ and not considered in detail in the present results.

Statistical analysis

For our analysis in general, we investigated persons who died in 2017 and used an observational period since 2014. Only for the differentiation, classification and analysis of the diagnosis groups, an observation period was defined as the 12-month period prior to the quarter of the year in which death occurred. Both confirmed outpatient diagnoses and principal and secondary inpatient diagnoses were analysed (see Table 1).

In 37 data sets, 40 treatments/prescription of all forms of palliative care services (out of >75,000 analysed palliative care performances) were accidentally dated after the date of death due to delays in the GPs’ documentation; in these instances, the final treatment date was converted to the date of death.

For hospital treatments, only full inpatient stays with at least one overnight stay were considered, as well as cases in which the person died on the day of hospital admission. In cases where the hospital discharge date was equivalent to the date of death, it was assumed that the person died in hospital.

The Social Science Statistics software (IBM SPSS Statistics), version 25, was used to calculate descriptive statistics (i.e. means, standard deviations, medians, minimum–maximum ranges).

Results

Study population: Sociodemographic and disease-related data

The mean age of the cohort at the time of death was 79.6 ± 12.4 years (range 18–107), with a gender distribution of 53.2% women and 46.8% men. Almost the entire study population suffered, amongst other conditions, from non-oncological chronic diseases (96.5%); approximately one-third (34.7%) had at least one cancer diagnosis.

Palliative care in the cohort

Approximately one-third of the cohort (31.4%, n = 11,155) received any type of outpatient palliative care prior to death. Of these, 27.7% received GPC, 8.8% received SPC, 0.5% received IPC and 1.8% received OS. For the remaining 68.6% (n = 24,359), no form of outpatient palliative care was documented in the observation period (group 4) (see Fig. 1).

Persons who received outpatient palliative care

Patients who received outpatient palliative care could be classified into three groups. Only GPC was received by 67.7% (n = 7549) of those with outpatient palliative care (group 1). Both GPC and additional outpatient palliative care (IPC, SPC and OS) were received by 20.5% (n = 2283) (group 2), and 11.9% (n = 1323) did not receive GPC but received another form of outpatient palliative care (group 3) (see Table 2, Fig. 1).

Switching between forms of outpatient care

The majority (78.6%; n = 8765) of the cohort received only one form of outpatient palliative care; 19.6% (n = 2190) received two forms, 1.7% (n = 193) received three forms and 0.1% (n = 7) received all four forms of outpatient palliative care.

Considering switching between GPC to SPC which occurred in n = 2000 cases, 70% (n = 1400) of them received GPC first and SPC subsequently; 15.6% (n = 312) received SPC first and GPC subsequently; and 14.4% (n = 288) received both on the same day.

Switches between GPC to OS were observed in n = 380 cases. The majority, 62.1% (n = 236), received GPC first and OS subsequently; 34.5% (n = 131) received OS first and GPC subsequently; and 3.4% (n = 13) received both on the same day.

OS and SPC were switched during the disease trajectory in a minority (n = 258) of the full cohort. Here, 62.8% (n = 162) received OS first and SPC subsequently; 26.7% (n = 69) received SPC first and OS subsequently; and 10.5% (n = 27) received both on the same day.

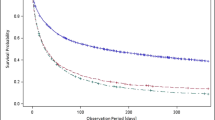

Integration of palliative care in the illness trajectory

The interval between the initiation/prescription of outpatient palliative care and death differed among all three forms of care. Persons receiving GPC services (n = 9832) had an average of 263.69 ± 377.82 days (range: 0–1455), those receiving SPC services (n = 3121) an average of 81.30 ± 165.12 days (range: 0–1429), and those receiving OS services (n = 634) an average of 259.07 ± 352.15 days (range: 0–1420) between the initiation/prescription of outpatient palliative care and their death. Overall, 6% of the cohort received outpatient palliative care more than 2 years before death. Details of the timing of service initiation/prescription are presented in Fig. 2.

Time of the first provision of GPC, SPC and OS in 30-day intervals as a cumulative share of all patients receiving outpatient palliative care (GPC = general outpatient palliative care; IPC = intermediate outpatient palliative care; SPC = specialised outpatient palliative care; OS = oncological palliative care services)

Hospitalisation during the last year of life and place of death

In total, 81.7% (n = 29,009) of the cohort received full inpatient care in a hospital during their last year of life.

In group 1, 81.9% of the cohort who received exclusively GPC had an average of 2.96 ± 2.22 hospital stays (range: 1–27), with an average of 30.57 ± 32.03 total hospital days in the last year of life. In this group, 31.1% died in hospital.

In group 2, 92.0% of the cohort who received GPC in combination with other outpatient palliative services had an average of 3.55 ± 2.59 hospital stays (range: 1–26), with an average of 36.12 ± 34.53 total hospital days in the last year of life. In this group, 19.9% died in hospital.

In group 3, 93.4% of the cohort who received outpatient palliative services other than GPC had an average of 3.34 ± 2.28 hospital stays (range: 1–18), with an average of 33.53 ± 31.02 total hospital days in the last year of life. In this group, 23.5% died in hospital.

In group 4, 80.0% of the cohort with no form of outpatient palliative care had an average of 2.57 ± 1.90 hospital stays (range: 1–33), with an average of 27.67 ± 30.23 total hospital days in the last year of life. In this group, 52.4% died in hospital (see Table 2).

Discussion

Using secondary data from the AOKN, the present study examined the delivery of outpatient palliative care in Lower Saxony, Germany. According to the data, 31.4% of the insured persons who died in 2017 received outpatient palliative care during the course of their illness; this figure is significantly below the estimated demand of up to 80% (Scholten et al. 2016). Although this demand figure does not exclusively refer to outpatient services, which was the sole consideration of our data, the results nonetheless provide a clear indication of an undersupply of outpatient palliative care (Soziale Pflegeversicherung 2021; Ditscheid et al. 2020; van Baal et al. 2020).

The present analysis of the distribution of specific forms of outpatient palliative care revealed considerable differences. In particular, GPC fell far short of the estimated demand, considering that general palliative care is necessary for the vast majority of seriously ill and dying patients (Scholten et al. 2016; Murray et al. 2015). In contrast, demand for SPC, at just under 10%, was generally consistent with the actual service provision (Melching 2015).

A palliative undersupply of GPC in Germany was already described in the Bertelsmann Foundation’s 2015 Health Fact Check, which recorded a national average rate of GPC in the last year of life at 24.2% and a Lower Saxony average of 28% (Radbruch et al. 2015). It is apparent that GPC has stagnated at a level that is insufficient to meet current estimates of need. While it could be argued that, in 2015, GPC had only been recently introduced (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin 2020) and may not have been used extensively, this argumentation does not apply to the current results. It is conceivable that the GPC data found in the present study reflect the fact that indications for palliative treatment at the end of life can be difficult to determine. In particular, the progression of non-cancer diseases is difficult to assess prognostically, as such diseases are characterised by intermittent crises and re-stabilisations (Murray et al. 2005); this can engender difficulty in identifying whether—and at what point in the illness trajectory—palliative care should be initiated. In particular in general practice, which is characterised by the long-term, continuous care of many (older) patients with chronically progressive diseases (Stiel et al. 2020), the timing of any transition to palliative care is frequently difficult to pinpoint. To improve the identification of patients who might benefit from outpatient palliative care, instruments such as the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT-DE) could be integrated into general practice (Afshar et al. 2018).

A further reason that the administration of GPC may be failing to meet the assumed demand pertains to the unclear demarcations and overlaps between GPC and other care approaches. For example, empirical findings from our work group have shown that, for GPs, the distinction and transition between palliative care concepts and geriatric care concepts is often unclear (Stiel et al. 2019). Moreover, the international literature describes difficulties inherent in GP palliative care relating to an unclear distribution of roles (Quill and Abernethy 2013), increasingly difficult communication and cooperation (Oishi and Murtagh 2014) with SPC providers, and uncertainty due to a subjective lack of palliative care experience, knowledge and skills (Malpas and Mitchell 2017).

The intervals between outpatient palliative care initiation/prescription and death show that GPC and OS were initiated, on average, almost 9 months prior to death; for SPC, in contrast, the interval was approximately 3 months. These results show that the different palliative care services are generally integrated into patient care at different points in time. Encouragingly, our data showed that SPC was integrated into the care trajectory at an earlier stage than during the years 2010–2014, when it was integrated at an average of 51 days before death (Radbruch et al. 2015). The early integration of outpatient palliative care makes sense in many cases, as it improves quality of life (Temel et al. 2010) and may even contribute to an extension of life (Temel et al. 2010) and fewer hospital stays (Hui et al. 2014).

Within the last year of life, all groups of analytic samples who received outpatient palliative care experienced more frequent and longer hospital stays than those who did not receive outpatient palliative care. A possible reason for this is that most patients who receive palliative care (including specialised services such as SPC and OS) suffer from an oncological disease. The present data are unable to determine the extent to which inpatient stays were planned, acute or (potentially) avoidable. However, data on the rate of hospital deaths were encouraging, showing that the proportion of patients who died in hospital was lower for those who received outpatient palliative care. This finding suggests that outpatient palliative care may contribute to enabling as many patients as possible to die in their own home or in an outpatient setting, but not in hospital, which is what most people prefer (Radbruch et al. 2019).

Strengths and limitations

The analysis of a large cohort of persons insured by the AOK Lower Saxony might provide valuable insights for palliative care in Germany, which is the major strengths of the present work. Moreover, the study sample was recruited from one of the largest German states, which features a mixture of small, medium and large urban agglomerations, as well as rural regions. One limitation is that all evaluations were based on descriptive secondary data. There were no further measures available (e.g. patients’ need for care, (lack of) access and quality of care, and possible under-, mis- or over-provision). In addition, distortions of the results are possible because the AOKN morbidity level might have exceeded that of other statutory health insurance funds (Geyer et al. 2019). The socioeconomic composition of the AOKN’s insurance population included a higher proportion of persons with lower professional qualifications than in Germany as a whole (Geyer et al. 2019). However, the age and sex distribution was consistent with that of Lower Saxony and Germany more broadly. Looking closer at details of our analysed data, we cannot differentiate whether prescriptions for SPC have led to actual SPC treatment, because patients may not have made use of this care.

Conclusions

Overall, early outpatient palliative care starting several months up to 2 years before death took place in a minor percentage of deceased. Outpatient palliative care starts rather late before death for most patients, but enables more people not to die in hospital (Dasch and Zahn 2021). However, far fewer people receive outpatient palliative care at the end of life than is estimated, according to current needs and demand assessments. This applies, in particular, to GPC. On the positive side, GPC is integrated comparatively early in treatment, in alignment with the recommendation for the early integration of palliative care in the trajectory of patients suffering from a chronic progressive disease.

Availability of data and material

The data sets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author at stiel.stephanie@mh-hannover.de on request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Afshar K, Feichtner A, Boyd K, Murray S, Junger S, Wiese B, Schneider N, Muller-Mundt G (2018) Systematic development and adjustment of the German version of the supportive and palliative care indicators tool (SPICT-DE). BMC Palliat Care 17(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0283-7

AOK Niedersachsen (2021) Wir versichern Niedersachsen. https://www.aok.de/pk/niedersachsen/inhalt/wir-versichern-niedersachsen/. Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Bausewein C, Voltz R, Radbruch L, Simon S (2015) Erweiterte S3-Leitlinie Palliativmedizin für Patienten mit einer nicht heilbaren Krebserkrankung - Langversion 2.1 – Januar 2020 - AWMF-Registernummer: 128/001-OL. https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/128-001OLe_KF_S3_Palliativmedizin_2018-12.pdf. Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Bundesmantelvertrag-Ärzte (2009) Vereinbarung über die qualifizierte ambulante Versorgung krebskranker Patienten „Onkologie-Vereinbarung“ (Anlage 7 zum Bundesmantelvertrag-Ärzte). In: Der GKV-Spitzenverband (Spitzenverband Bund der Krankenkassen), Körperschaft des öffentlichen Rechts, Berlin, die Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung Körperschaft des öffentlichen Rechts, Berlin. https://www.aok.de/gp/fileadmin/user_upload/Arzt_Praxis/Aerzte_Psychotherapeuten/Vertraege_Vereinbarungen/Vertraege_Bayern/by_onkologievereinbarung_anlage7_bmv_aerzte_2016.pdf. Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Bundesmantelvertrag-Ärzte (2016) Vereinbarung nach § 87 Abs. 1b SGB V zur besonders qualifizierten und koordinierten palliativ-medizinischen Versorgung. https://www.kbv.de/media/sp/Anlage_30_Palliativversorgung.pdf. Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Dasch B, Zahn P K (2021) Place of death trends and utilization of outpatient palliative Care at the end of life-analysis of death certificates (2001, 2011, 2017) and Pseudonymized data from selected palliative medicine consultation services (2017) in Westphalia, Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int 118 (forthcoming). https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0124

de Meijer C, Wouterse B, Polder J, Koopmanschap M (2013) The effect of population aging on health expenditure growth: a critical review. Eur J Ageing 10:353–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-013-0280-x

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin (2013) Arbeitspapier zur allgemeinen ambulanten Palliativversorgung (AAPV) - Stand 23.04.2013. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin und Deutscher Hospiz- und Palliativverband e.V. https://www.dgpalliativmedizin.de/images/stories/20130422_Arbeitspapier_DGP_DHPV.pdf. Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin (2020) Entwicklung der allgemeinen ambulanten Palliativversorgung. https://www.dgpalliativmedizin.de/allgemein/allgemeine-ambulante-palliativversorgung-aapv.html Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Information (2020) Internationale statistische Klassifikation der Krankheiten und verwandter Gesundheitsprobleme 10. Revision German Modification Version 2020 https://wwwdimdide/static/de/klassifikationen/icd/icd-10-gm/kode-suche/htmlgm2020/ Acessed 6 September 2021

Ditscheid B, Krause M, Lehmann T, Stichling K, Jansky M, Nauck F, Wedding U, Schneider W, Marschall U, Meissner W, Freytag A, die SAVOIR-Studiengruppe (2020) Palliative care at the end of life in Germany: utilization and regional distribution. Bundesgesundheitsbl Gesundheitsforsch Gesundheitsschutz 63:1502–1510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-020-03240-6

Geyer S, Tetzlaff J, Eberhard S, Sperlich S, Epping J (2019) Health inequalities in terms of myocardial infarction and all-cause mortality: a study with German claims data covering 2006 to 2015. Int J Public Health 64:387–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-019-01224-1

Hui D, Kim S H, Roquemore J, Dev R, Chisholm G, Bruera E (2014) Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Wiley Online Library https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28628. Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Institut des Bewertungsausschusses (2013) Erratum zum Beschluss des Bewertungsausschusses nach § 87 Abs. 1 Satz 1 SGB V in seiner 309. Sitzung am 27. Juni 2013, pp. 15–17. https://www.sozialgesetzbuch-sgb.de/sgbv/87.html. Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (2021) Einheitlicher Bewertungsmaßstab (EBM). Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung, Berlin https://www.kbv.de/media/sp/EBM_Gesamt_-_Stand_1._Quartal_2021.pdf. Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Malpas PJ, Mitchell K (2017) "doctors Shouldn’t underestimate the power that they have": NZ doctors on the Care of the Dying Patient. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 34:301–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909115619906

Melching H (2015) Palliativversorgung - Modul 2: Strukturen und regionale Unterschiede in der Hospiz- und Palliativversorgung. Faktencheck Gesundheit. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/publikationen/publikation/did/faktencheck-palliativversorgung-modul-2. Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A (2005) Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 330:1007–1011. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1007

Murray SA, Firth A, Schneider N, Van den Eynden B, Gomez-Batiste X, Brogaard T, Villanueva T, Abela J, Eychmuller S, Mitchell G, Downing J, Sallnow L, van Rijswijk E, Barnard A, Lynch M, Fogen F, Moine S (2015) Promoting palliative care in the community: production of the primary palliative care toolkit by the European Association of Palliative Care Taskforce in primary palliative care. Palliat Med 29:101–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216314545006

Oishi A, Murtagh FE (2014) The challenges of uncertainty and interprofessional collaboration in palliative care for non-cancer patients in the community: a systematic review of views from patients, carers and health-care professionals. Palliat Med 28(1081-1098). https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216314531999

Quill TE, Abernethy AP (2013) Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 368:1173–1175 http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1215620. Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Radbruch L, Andersohn F, Walker J (2015) Faktencheck Gesundheit: Palliativversorgung – Modul 3 – Überversorgung kurativ – Unterversorgung palliativ? Analyse ausgewählter Behandlungen am Lebensende. www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de. https://faktencheck-gesundheit.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/Studie_VV__FCG_Ueber-Unterversorgung-palliativ.pdf. Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Radbruch L, Maier BO, Bausewein C (2019) Ambulante Palliativversorgung. Schmerz 33:285–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00482-019-0385-z

Scholten N, Günther AL, Pfaff H, Karbach U (2016) The size of the population potentially in need of palliative care in Germany - an estimation based on death registration data. BMC Palliat Care 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0099-2

Soziale Pflegeversicherung (2021) Sozialgesetzbuch (SGB) - Elftes Buch (XI) §14 Begriff der Pflegebedürftigkeit. Bundesamt für Justiz, Germany

Spezialisierte Ambulante Palliatvversorgung (2019) Social Security Code V §37b Sozialgesetzbuch V, Germany

Statistikportal (2018) Fläche und Bevölkerung nach Ländern. Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder. https://www.statistikportal.de/de/bevoelkerung/flaeche-und-bevoelkerung. Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Statistisches Bundesamt (2019) Bevölkerung im Wandel: Ergebnisse der 14. koordinierten Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung. https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressekonferenzen/2019/Bevoelkerung/pressebroschuere-bevoelkerung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Accessed 6 Sept 2021

Stiel S, Krause O, Berndt CS, Ewertowski H, Muller-Mundt G, Schneider N (2019) Caring for frail older patients in the last phase of life: challenges for general practitioners in the integration of geriatric and palliative care. Z Gerontol Geriat 53:763–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00391-019-01668-3

Stiel S, Ewertowski H, Krause O, Schneider N (2020) What do positive and negative experiences of patients, relatives, general practitioners, medical assistants, and nurses tell us about barriers and supporting factors in outpatient palliative care? A critical incident interview study. Ger Med Sci 18:Doc08. https://doi.org/10.3205/000284

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733–742. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1000678

van Baal K, Schrader S, Schneider N, Wiese B, Stahmeyer JT, Eberhard S, Geyer S, Stiel S, Afshar K (2020) Quality indicators for the evaluation of end-of-life care in Germany - a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of statutory health insurance data. BMC Palliat Care 19:187. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00679-x

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. ALLPRAX (BMBF FK 01GY1610) by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research of Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AW, SSt, MH and JS conceived and designed the study. MH and JS provided the data. MH and JS analysed the data and provided results. AW wrote and edited the manuscript draft, tables, and figures. SSt contributed substantially to conception and design of the study. SSt co-drafted and co-edited the manuscript. NSch enhanced the quality of the manuscript by revising it critically for important intellectual content, based on his long-standing expertise in the social sciences, public health research and primary palliative care.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding either this work or its funding body.

Ethics approval

Ethics Commission of the Hannover Medical School (MHH) (No. 7260, February 14, 2017) and the Data Protection Officer of the MHH has given positive feedback on the study design.

All data for the cohort were processed, anonymised and evaluated by the AOKN before being shared with the study team. Results were stored on a secure and password-protected institutional server.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Given by all authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Willinger, A., Hemmerling, M., Stahmeyer, J.T. et al. The frequency and time point of outpatient palliative care integration for people before death: an analysis of health insurance data in Lower Saxony, Germany. J Public Health (Berl.) 31, 1351–1359 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01672-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01672-1