Abstract

Aim

This study aimed at comparing health literacy measures, and their correlates, for the district of Favoriten to those of Vienna and Austria. The Viennese district of Favoriten was of particular interest, due to present characteristics, such as its high cultural and ethnic diversity as well as a relatively high unemployment rate.

Subject and methods

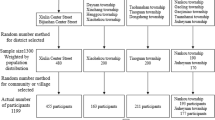

This study was set up as a cross-sectional, paper-based self-completion random sample survey. For each sample representing Favoriten, Vienna, and Austria, 500 adults were randomly drawn from the population register.

Results

Out of 1500 surveys sent out, 160 (10.7%) were included in the analysis. Regarding general health literacy, the sample of Favoriten scored highest (33.9; CI 95% 31.5, 36.3), followed by the samples of Austria (32.5; CI 95% 30.9, 34.2) and Vienna (31.5; CI 95% 29.6, 33.4). Higher household income (r = 0.46, p < 0.01), better education (r = 0.31, p = 0.09) and migration status outside the EU (d = −0.56, p = 0.12) showed moderately effect-sized associations to general health literacy in the sample of Favoriten, which was not the case for other characteristics such as age, gender, and employment status.

Conclusion

In the light of previous studies, reporting on associations of health literacy measures with social determinants, such as migration and employment status, the sample of Favoriten might well have been expected to result in impaired health literacy measures. Our results do not support this assumption, though. Despite the limited external validity of this study, policymakers and practitioners may be advised to design health literacy measures in such a way that specifically reaches out to the socially disadvantaged target population and not focus merely on pertinent districts or regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The concept of health literacy aims at empowering people to make decisions in order to improve or maintain a good quality of life throughout the entire life course. The term health literacy has been defined in numerous ways and is still considered an evolving and expanding concept (Rudd 2017). Within the WHO Health Promotion Glossary of 1998, health literacy was defined as the cognitive and social skills which determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health (WHO 1998). Sorensen et al. identified 17 definitions and 12 conceptual models of health literacy. Based on content analysis, they developed an integrative conceptual model containing 12 dimensions referring to the knowledge, motivation, and competencies of accessing, understanding, appraising, and applying health-related information within the healthcare, disease prevention, and health promotion settings respectively (Sørensen et al. 2012). A corresponding health literacy measurement instrument was derived from this model and used in a cross-national European survey: the European Health Literacy Survey (HLS EU) (Pelikan et al. 2012). An Austrian follow-up to this found weak, but statistically significant, associations of health literacy with gender, age, education, social status, and financial deprivation, as well as migration and employment status. The strongest correlation thereof was reported for financial deprivation (r = −0.29) (Pelikan et al. 2013). A systematic review of health literacy assessments of adults conducted in the United States up to 2004 found the prevalence of low health literacy to be associated with education, ethnicity, and age, whereas no associations were found with gender and measurement instrument (Paasche-Orlow et al. 2005). A study on African Americans found limited health literacy to be associated with gender, unemployment, and income (Davis et al. 2020). A recent Japanese nationally representative study found good self-reported health to be associated with younger age, employment, and higher communicative/critical health literacy, and hence concluded that policy interventions should focus on the promotion of health literacy among deprived sociodemographic groups (Furuya et al. 2015). An analysis of data of the Health Survey for Catalonia found education level, socioeconomic status, and physical limitations to be the factors with the strongest contribution to limited health literacy (Garcia-Codina et al. 2019). A recent Swiss exploratory study found lower functional health literacy in immigrants and length of stay in a country to be associated with language-dependent health literacy (Mantwill and Schulz 2017). A qualitative study of immigrant women in Taiwan highlighted that limited language and health literacy skills hinder access to proper health care (Tsai and Lee 2016). Low general literacy has also been shown to be associated with several adverse health outcomes (Dewalt et al. 2004).

With more than 200,000 residents, Favoriten is Vienna’s largest populated district, accounting for 10.8% of the city’s total population (Statistics Austria 2018). As compared to other districts, Favoriten has a relatively high unemployment rate, accounting for 14% of Vienna’s total unemployment (City of Vienna, MA 23 2018). With 49%, Favoriten has amongst 23 Viennese districts the third-highest share of residents of foreign origin (City of Vienna 2019). The Austrian HLS EU follow-up, which represents the most recent national health literacy survey, has identified modest associations of health literacy with social determinants such as migration status, education, self-indicated social status, financial deprivation, and employment (Pelikan et al. 2013). Consequently, our present study should contribute to this field with novel insights into the current characteristics of health literacy in a socially deprived urban district.

This study aimed at gathering insights into the characteristics of health literacy in the Viennese district of Favoriten, as compared to the city of Vienna and the entire state of Austria. Moreover, associations of health literacy with demographic characteristics and dimensions of social inequality such as gender, age, migration status, and employment status should be identified. Following the HLS-EU (Pelikan et al. 2012) and its Austrian national follow-up conducted in 2013 (Pelikan et al. 2013), the present survey delivers recent data concerning the health literacy of the Austrian and Viennese adult population. However, the primary research question was whether health literacy measures of adults in Favoriten differ from those in the city of Vienna and the state of Austria. Based on previous research, we hypothesized that people living in the district of Favoriten, with lower socioeconomic status, would have lower health literacy compared with other Austrian regions with higher socioeconomic status.

Materials and methods

Study design and outcome measures

This study was set up as a cross-sectional paper-based random sample survey. Three samples, each encompassing 500 persons, of men and women aged 18 to 64 years, having their principal residence registered in Favoriten, Vienna, or Austria, were randomly drawn from the central population register. The survey was only provided in German, and therefore it is assumed that only German-speaking recipients completed the survey. Persons having their residence in Favoriten were not excluded from the citywide and national sample, and persons having their residence in Vienna were not excluded from the national sample. The number of 500 subjects per sample was selected with respect to feasibility. The existing survey HLS-EU-Q47 developed within the HLS EU Project 2009-2012 was provided with permission via Gesundheit Österreich GmbH. The survey follows the holistic model of health literacy which integrates medical and public health views considering the domains of healthcare, prevention, and health promotion in combination with the ability of accessing, understanding, processing, and applying information (Sørensen et al. 2012). Respondents rated their perceived difficulty on a pre-coded four-point Likert scale (very easy, rather easy, rather difficult, very difficult) (Pelikan et al. 2012). Answers were scored assigning one point for the most positive answer very easy and four points for the least positive answer very difficult. The general and the three domain-specific health literacy scores were transformed towards a comparable minimum of 0 points and a maximum of 50 points, as described by Pelikan et al. Scores were furthermore classified by means of the following cut-offs: 0–25 points — inadequate, > 25–33 points — problematic; > 33–42 points — sufficient; > 42–50 points — excellent (Pelikan et al. 2013). The threshold below 26 points reflects that those individuals who were classified into inadequate health literacy rated at least 50% of the items as very difficult or rather difficult (Pelikan et al. 2013). Internal consistency of the HLS-EU-Q47 survey expressed as Cronbach’s alpha was assessed to be reasonably high across Europe, ranging from 0.95 to 0.99 for general health literacy and from 0.87 to 0.92 for the domain-specific scores. All items have been shown to correlate higher than 0.3 (Pearson’s r) with the respective index, indicating adequate selectiveness of all items included. With respect to content- and face validity, the HLS-EU-Q47 survey was developed in a stepwise and participative approach by an international expert consortium (Pelikan et al. 2012). Agreement with the Newest Vital Sign Test (Rowlands et al. 2013), as a measure of functional health literacy, was on average weak across Europe (r = 0.25). Due to reasons of feasibility, the existing survey designed for telephone interviews was adapted to a paper-based self-completion version. The best possible congruence with the telephone interview version was aimed for. A one-page invitation letter and a return envelope with printed address and mail charge clearance were added to the sending. Consequently, participation did not cause any costs for those taking part in the survey. The invitation letter included information on the aim of the study and how to complete and return the survey, as well as measures taken to ensure anonymity. In terms of anonymity, participants were asked not to indicate any information such as the name or address of the sender, in order to disable the identification of the person. Returned surveys were included in the analysis, if the survey came back within a period of 8 weeks, at least 23 questions (50%) were answered accurately, and the general score, as well as the three domain-specific scores, could be calculated. The general health literacy score has been suggested to require a minimum of 43 valid answers out of 47 questions. With regard to sub-scores, the domain healthcare requires a minimum of 15 valid answers out of 16 questions, the domain disease prevention requires a minimum of 14 valid answers out of 15 questions, and the domain health promotion requires a minimum of 15 valid answers out of 16 questions (Pelikan et al. 2013). In terms of measures to maximize response rate, the return period was extended from the initially foreseen 4 to 8 weeks (19 Feb to 16 Apr 2019), and a reminder letter was sent to the sample of Favoriten.

The Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of Vienna approved the study protocol and related material (EK Nr. 2228/2018). The invitation letter informed that participation in the survey was voluntary and about data being processed anonymously. Consequently, the need for consent was waived by the aforementioned Institutional Review Board.

Statistical analysis

Undesirable answers very difficult and rather difficult were aggregated in a secondary outcome expressed as a percentage. Except for the sample characteristics, all data underwent a re-harmonization procedure for gender and age using six strata (two genders by three age groups: 18–34 years, 35–49 years, and 50–64 years). Reference rates for the weighting factors were taken from the Austrian population statistics, as per January 2018 (Statistics Austria 2018), and divided by the actual rates to obtain the weighting factors for each stratum. All data were inspected for outliers by boxplots and tested for the assumption of normality by Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests and graphical inspection of q–q-plots. ANOVA was applied to test differences between the three regions. No contrasts were defined a priori. Gabriel’s procedure was applied for multiple posthoc comparisons. This procedure provides greater power than conservative approaches, such as Bonferroni, and is being suggested when variances are equal and sample sizes are slightly different (Field 2013). Associations of health status, lifestyle, demographic, and socioeconomic characteristics with the general health literacy were assessed by Spearman’s correlations. Effect sizes were interpreted according to the scheme of Cohen (Cohen 1988). Alpha was set at 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics in its recent version (IBM Corp 2018).

Results

Participants

After the exclusion of seven surveys due to partial completion, 160 (10.7%) out of 1500 surveys were included in the analysis. The number of valid responses was higher in the Austrian sample (n = 71) as compared to the sample of Vienna (n = 47) and the sample of Favoriten (n = 42). There were more women than men amongst the valid respondents (57.5%). The mean age was 44.2 years (sd 13.1). Participants from Favoriten reported a markedly lower median household net income category (1850–2399€) as compared to participants from Vienna (3600–4399€). However, the self-rated social status was in Favoriten only slightly below that of the Viennese and Austrian samples (Table 1). Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) tests supported the assumption of normality in all three samples with regard to the four health literacy scores, except for the score healthcare' in the Vienna sample [KS(47): 0.13, p = 0.03)]. However, a graphical inspection of the respective q–q plot did not show a major violation, and hence parametric presentation and test procedures were carried out consistently, except for correlations of general health literacy with health status, lifestyle behavior, and demographic characteristics.

Comparison of health literacy levels in the samples of Favoriten, Vienna, and Austria

Figure 1 shows percentage shares of levels of general and domain-specific health literacy in the samples of Favoriten, Vienna, and Austria. The sum of inadequate and problematic health literacy has also been referred to as limited health literacy, whereas the sum of sufficient and excellent health literacy has been referred to as non-limited health literacy (Pelikan et al. 2013). With regard to general health literacy, the sample of Favoriten showed a lower share of inadequate health literacy, for the benefit of excellent health literacy, as compared to the samples of Vienna and Austria. This causes a somewhat lower share of limited health literacy (52.9%) in Favoriten, as compared to Vienna (64.1%) and Austria (56.6%). The same thing applies equally to the three domain-specific health literacy classifications. The share of limited health literacy was relatively low in the domains of healthcare (FAV: 14.5%, W: 33.9%, AT: 23.8%) and health promotion (FAV: 17.5%, W: 33.9%, AT: 30.9%).

Percentage shares of levels of general and domain-specific health literacy. Samples: Favoriten (FAV) (n = 42), Vienna (W) (n = 47), and Austria (AT) (n = 71). Blue: inadequate (0–25 points); orange: problematic (> 25–33 points); grey: sufficient (> 33–42 points); yellow: excellent (> 42–50 points) (Pelikan et al. 2013)

Comparison of health literacy scores in the samples of Favoriten, Vienna, and Austria

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics of general and domain-specific health literacy scores in the samples of Favoriten, Vienna, and Austria. Table 3 shows the corresponding test statistics providing effect sizes and p-values of multiple comparisons across the three samples. For general health literacy and the three domains, the sample of Favoriten resulted in the highest scores, whereas the sample of Vienna resulted in the lowest scores. However, effect sizes were either small or negligible and except for the comparison of the score healthcare between Favoriten and Vienna (d = 0.47, p = 0.04), none of these differences was statistically significant at the level of 0.05.

Correlates of general health literacy

Table 4 shows correlates of general health literacy in the samples of Favoriten, Vienna, and Austria. Variation in sample sizes results from the exclusion of cases where participants selected the option I do not know/no indication. Self-perceived social status in the Viennese sample resulted in the highest association with health literacy (Rho = 0.49, p = 0.00). Observed effects varied fairly in between the three samples. While higher household income showed a moderate association in the sample of Favoriten, this was not the case in the samples of Vienna and Austria. Better education was in Favoriten and Vienna moderately correlated with general health literacy, but not so in the Austrian sample. In the Favoriten sample, participants with migration background outside the European Union (mean = 31.6, sd = 7.5, n = 12) had a lower general health literacy score than those without such a background (mean = 35.5, sd = 6.5, n = 25). This difference (−3.82), t(35) = 1.58 was not statistically significant (p = 0.12), however it represents a medium sizes effect (d = −0.56). Female participants (mean = 34.0, sd = 7.7, n = 20) had in this sample almost similar general health literacy scores, compared to male participants (mean = 33.8, sd = 7.9, n = 81).

Discussion

With regard to general and domain-specific health literacy, Favoriten had the highest and Vienna had the lowest scores, with Austria consequently being in the middle. However, only one of these comparisons, opposing the score' healthcare' between Favoriten and Vienna, resulted in a statistically significant difference. The hypothesis of lower health literacy in the socially deprived district of Favoriten was consequently rejected. The percentage of limited health literacy in Austrian adults was similar (56.4% vs 56.6%) as compared to the result from the HLS EU 2012 survey (Pelikan et al. 2012). In line with previous studies, higher household income (Pelikan et al. 2013; Davis et al. 2020), better education (Pelikan et al. 2013; Paasche-Orlow et al. 2005; Garcia-Codina et al. 2019), and migration status (Pelikan et al. 2013) were in the sample of Favoriten associated to general health literacy, with effect sizes being moderate. In contrast to previous studies reporting associations of health literacy with age (Pelikan et al. 2013; Paasche-Orlow et al. 2005; Furuya et al. 2015), gender (Pelikan et al. 2013; Davis et al. 2020), and employment status (Pelikan et al. 2013; Davis et al. 2020; Furuya et al. 2015), we found only negligible effects in this context. Correlates of health literacy varied largely in between the three samples.

Questions related to calling an ambulance in an emergency, judging where life affects health and well-being, and judging how housing conditions help to stay healthy, resulted in the Favoriten sample in a remarkably higher prevalence of undesirable answers (very difficult or rather difficult), as compared to the samples of Vienna and Austria. In contrast, questions related to understanding what the doctor says, understanding the leaflet that comes with the medicine, and finding out how political changes that may affect health, resulted in a remarkably lower prevalence of undesirable answers. A low level of health literacy in a region can be interpreted in different ways; either the population has specifically low competencies, or the health system is characterized by specifically high demands, or a mixture of both (Pelikan et al. 2012). Considering the excellent Austrian health care system — fourth highest health care expenditure relative to GDP in 2017 within the EU (Eurostat 2020) — low health literacy may predominantly be attributable to low population competencies. However, fewer difficulties with reading instruction leaflets or understanding what the doctor says may also arise from an elevated share of people who rarely read instruction leaflets or visit physicians.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The internal validity based on the data collection process and analysis applied equally to the three samples, and the large randomly drawn sample can be considered a strength of the study. The relatively low rate of 10.7% being included in the analysis, in contrast, represents a considerable weakness, involving the risk of attrition bias and systematic exclusion of people with low health literacy, including those without an adequate command of the German language. In addition, the low and presumed selective response, the relatively low general number of cases (n = 160) limits the generalizability and statistical power of the test statistics. Methodological differences with regard to the data assessment (paper-based survey vs telephone interview) have to be kept in mind when comparing results from previous research with the present study. The study design did not permit taking the situation of people into account who are unable to read and complete a German questionnaire, and those not being included in the population register. Generally, correlations can be caused partly or fully by confounders and should be interpreted accordingly.

Conclusion

According to associations of health literacy with social determinants as reported in previous studies, such as and migration status and employment status, the district of Favoriten might well be expected to result in impaired health literacy measures. However, our results do not support this assumption. Hence, policymakers and practitioners may be advised to design health literacy measures in such a way that specifically reaches out to the socially disadvantaged target population, and not to focus merely on pertinent districts or regions. Nonetheless, measures to convey health literacy specifically to the people of Favoriten may put special emphasis on how to call an ambulance in the case of an emergency, judging where life affects health and well-being, and judging how housing conditions help people to stay healthy. Further research may focus on investigating the health literacy of people affected by language barriers in socially deprived areas, and the efficacy of related measures such as translation services. New assessment concepts should handle language barriers and follow a more focused approach, e.g. via key opinion leaders into certain population strata.

References

City of Vienna (2019) Wiener Bevölkerung — Staatsbürgerschaft, Herkunft, Bezirke, Zuwanderung, Abwanderung, Wahlrecht. Stadt Wien, Vienna. https://www.wien.gv.at/menschen/integration/daten-fakten/bevoelkerung-migration.html. Accessed 04 Sept 2019

City of Vienna, MA 23 (2018) Arbeitslose (inkl. SchulungsteilnehmerInnen) nach Bezirk und Geschlecht 2018. Stadt Wien, Vienna. https://www.wien.gv.at/statistik/arbeitsmarkt/tabellen/arbeitslos-bezirk.html-bez-zr.html. Accessed 04 September 2019

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ

Davis SN, Wischhusen JW, Sutton SK, Christy SM, Chavarria EA, Sutter ME, Roy S, Meade CD, Gwede CK (2020) Demographic and psychosocial factors associated with limited health literacy in a community-based sample of older black Americans. Patient Educ Couns 103(2):385–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.08.026

Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP (2004) Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med 19(12):1228–1239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x

Eurostat (2020) Healthcare expenditure statistics 2017. European Statistical Office, Luxembourg. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Healthcare_expenditure_statistics#Healthcare_expenditure. Accessed May 2020

Field A (2013) Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: and sex and drugs and rock'n'roll, 4th edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Furuya Y, Kondo N, Yamagata Z, Hashimoto H (2015) Health literacy, socioeconomic status and self-rated health in Japan. Health Promot Int 30(3):505–513. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dat071

Garcia-Codina O, Juvinyà-Canal D, Amil-Bujan P, Bertran-Noguer C, González-Mestre MA, Masachs-Fatjo E, Santaeugènia SJ, Magrinyà-Rull P, Saltó-Cerezuela E (2019) Determinants of health literacy in the general population: results of the Catalan health survey. BMC Public Health 19(1):1122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7381-1

IBM Corp (2018) SPSS. IBM Corp., Armonk, NY

Mantwill S, Schulz PJ (2017) Does acculturation narrow the health literacy gap between immigrants and non-immigrants-an explorative study. Patient Educ Couns 100(4):760–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.021

Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR (2005) The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med 20(2):175–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40245.x

Pelikan JM, Röthlin F, Ganahl K (2012) Comparative Report of the HLS-EU Project. HLS-EU Consortium. https://cdn1.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/135/2015/09/neu_rev_hls-eu_report_2015_05_13_lit.pdf. Accessed 03 Mar 2020

Pelikan JM, Röthlin F, Ganahl K (2013) Die Gesundheitskompetenz der österreichischen Bevölkerung — nach Bundesländern und im internationalen Vergleich. Abschlussbericht der Österreichischen Gesundheitskompetenz (Health Literacy) Bundesländer-Studie. LBIHPR Forschungsbericht.

Rowlands G, Khazaezadeh N, Oteng-Ntim E, Seed P, Barr S, Weiss BD (2013) Development and validation of a measure of health literacy in the UK: the newest vital sign. BMC Public Health 13:116. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-116

Rudd RE (2017) Health literacy: insights and issues. Stud Health Technol Inform 240:60–78

Sørensen K, van den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z, Brand H (2012) Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 12:80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-80

Statistics Austria (2018) Population Statistics 2018. Statistics Austria, Vienna

Tsai T-I, Lee S-YD (2016) Health literacy as the missing link in the provision of immigrant health care: a qualitative study of southeast Asian immigrant women in Taiwan. Int J Nurs Stud 54:65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.03.021

WHO (1998) Health Promotion Glossary. WHO, Geneva. https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/about/HPG/en/. Accessed 03 Mar 2020

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the scientific merit of the HLS EU consortium. Special thanks go to the student collaborators Justin Dyett, Verena Kircher, and Simone Löffler, as well as all participants who completed and returned the survey. No external funding was obtained.

Availability of data and material (data transparency)

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability (software application or custom code)

Not applicable.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FH Campus Wien - University of Applied Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PP and AP developed the study protocol and obtained ethical approval. AP and PP collected and analyzed the data. PP wrote the first draft. AP reviewed and commented on subsequent drafts of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/competing interests (include appropriate disclosures)

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval (include appropriate approvals or waivers)

The Institutional Review Board of the Medical University of Vienna approved the study protocol and related material (EK Nr. 2228/2018).

Consent to participate (include appropriate consent statements)

The invitation letter informed that participation in the survey was voluntary and about data being processed anonymously. Consequently, the need for consent was waived by the aforementioned Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication (consent statement regarding publishing an individual’s data or image)

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Putz, P., Patek, A. Health literacy measures are not worse in an urban district high in migration and unemployment compared to a citywide and a national sample. J Public Health (Berl.) 31, 947–954 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01612-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01612-z