Abstract

Aim

Electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) use among Irish teenagers has risen significantly. In 2019, prevalence of current use (last 30 days) among 15–17-year-olds was 17.3%. We examine social determinants of adolescent e-cigarette current use.

Subject and methods

A stratified random sample of 50 schools in Ireland was surveyed in 2019, part of the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and other Drugs (ESPAD), with 3495 students aged 15, 16, and 17. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression [providing adjusted odds ratios (AORs)] analyses were performed using Stata version 16.

Results

Current e-cigarette users were more likely to be male (AOR = 0.55, 95% CI:0.32–0.96, p < .01), younger (AOR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.17–0.67, p = < .05), to participate in sport (AOR = 2.21, 95% CI: 1.05–4.65, p < .05), to have higher-educated parents (maternal higher education: AOR = 27.54, 95% CI: 1.50–505.77, p = < .05, paternal higher education: AOR = 2.44, 95% CI: 1.00–5.91, p < .05), and less likely to consider their families better off (AOR = 0.29, 95% CI: 0.13–0.65, p < .01), or to report familial support (AOR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.64–0.95, p < .05). They were more likely to be cigarette smokers (AOR = 7.22, 95% CI: 3.97–13.12, p < .001), to report problem cannabis use (AOR = 3.12, 95% CI: 1.40–6.93, p < .01), to be ‘binge’ drinkers (AOR = 1.81, 95% CI : 1.00–3.32, p = .054), and to have friends who get drunk (AOR = 5.30, 95% CI: 1.34–20.86, p < .05).

Conclusion

Boys, smokers, binge drinkers, problem cannabis users, and sport-playing teenagers from higher-educated families, are at particular risk. As the number of young people using e-cigarettes continues to rise, including teenagers who have never smoked, improved regulation of e-cigarettes, similar to other tobacco-related products, is needed urgently to prevent this worrying new trend of initiation into nicotine addiction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

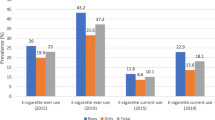

E-cigarette use among young people in Ireland has risen significantly in recent years, and among 15–17-year-olds, prevalence is now 37% for ever-use and 17.3% for current use (Sunday et al. 2020). The increase has been particularly steep since 2016 (Hanafin et al. 2021). Among young people who use e-cigarettes, 67% of them have never smoked combustible cigarettes (Sunday et al. 2020), representing a worrying new trend of initiation into nicotine addiction. Increasing prevalence in Ireland reflects similarly high rates elsewhere in Europe (ESPAD Group 2020; Kapan et al. 2020), the US (Evans-Polce et al. 2020; Gentzke et al. 2019) and the Asia-Pacific region (Wills et al. 2017). The 2019 European School Project on Alcohol and Drugs (ESPAD) survey (ESPAD Group 2020) of 99,647 students from 35 countries in Europe reported an average of 40% ever-use of e-cigarettes among students aged 15–16 years, ranging from 18% in Serbia to 65% in Lithuania. Average current use (during the last 30 days) was 14%, which is lower than in Ireland, with a range of 5.4% (Serbia) to 41% (Monaco). Prevalence of regular use in Scotland (once a week or more) was 3% (Scottish Government 2019). Increasing prevalence is not reported everywhere, however. In England between 2016 and 2018 there was no increase, with reported prevalence for current and regular e-cigarette prevalence remaining at 6% and 2% respectively (National Statistics, 2019).

Modern e-cigarettes were commercially developed in 2003 as an alternate nicotine delivery device for tobacco smokers (Bozier et al. 2020). E-cigarettes entered the US marketplace around 2007, and since 2014, they have been the most commonly used tobacco product among US youth, having risen to epidemic proportions (U.S. Surgeon General 2018). Between 2017 and 2018, e-cigarette current use among high school students increased 77.8% from 11.7% to 20.8% (Gentzke et al. 2019). The more recent evolution of “pod-mod” e-cigarettes such as JUUL introduced in 2015 is associated with an increase in e-cigarette use by youth and young adults in the US (Huang et al. 2018). In European countries, there is a higher prevalence of e-cigarette use among males, adolescents, and young adults, smokers of conventional combustible cigarettes, and former smokers (Kapan et al. 2020).

While it is generally accepted that e-cigarette ‘vapour’ (i.e., the cloud of aerosol/mist/fog released by an e-cigarette) contains fewer toxicants than tobacco smoke, it still contains numerous toxicants, including nicotine (in the majority of e-liquids), the humectants propylene glycol and glycerine, flavour additives, and the presence of metal contaminants (Bozier et al. 2020). Reports from the Office of the Surgeon General (US Surgeon General 2018; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2014, 2016) drew attention to the effects of nicotine exposure during adolescence in terms of its impact on learning, memory, and attention, as well as increased risk for future addiction to other drugs. Adolescents, however, are often uninformed about the constituents of e-cigarettes, both in the US (Fadus et al. 2019) and in Europe (Kinnunen et al. 2020). Pulmonary risks of e-cigarette use have also emerged, including the condition electronic-cigarette/vaping associated lung injury (EVALI) as well as extrapulmonary cardiovascular, immunologic, and neuro-developmental effects (Overbeek et al. 2020).

Recurring themes in debates about e-cigarettes include lack of consensus among the tobacco control community about harm reduction, effects on tobacco control, and whether or not (or the extent to which) e-cigarettes act as a gateway drug, particularly for young people (Grana and Ling 2014). The first UK study to assess whether younger (aged 13–14 years at baseline) adolescent e-cigarette use was associated prospectively (at 12 months) with initiation or escalation of cigarette use found that ever-use of e-cigarettes was robustly associated with initiation but more modestly related to escalation of cigarette use (Conner et al. 2018; McCarthy et al. 2020). Young never-smokers in Scotland who had tried an e-cigarette were more likely to try a cigarette during the following year than those who had not (Best et al. 2018).

Since 1995, smoking prevalence has been decreasing in Ireland, markedly so among young people, with a 66% decline in 16–17-year-olds between 1995 and 2015 (Li et al. 2018). Now, for the first time in 25 years this decrease has stalled, with prevalence rates (30-day use) of smoking among young people in 2019 remaining the same (14.4%) as they were in 2015, accounted for by a notable increase in smoking prevalence among boys (16.2%), and a slight decrease among girls (12.8%) (Sunday et al. 2020). This halt in smoking prevalence reduction despite continued strong tobacco control measures has been accompanied by a rising prevalence of e-cigarette use, pointing to a possible link. Although marketed as a smoking cessation tool, e-cigarettes are rarely used for this purpose in youth (Fadus et al. 2019; Hanafin and Clancy 2020). Among adolescents in Ireland, the main motivation for using e-cigarettes was curiosity (66%) and because friends offered (29%), while only 3.4% said that their motivation was for smoking cessation (Sunday et al. 2020). Given the stark increase in e-cigarette experimentation and continued use among 15–17-year-olds in Ireland, we set out to establish a profile of young e-cigarette users. We examine socio-demographic, individual, peer, and familial associations with e-cigarette current use among 15–17-year-olds in Ireland.

Methods

Design, sample, data collection

A total of 3565 students aged 15, 16, and 17 years old were surveyed in 2019 for the Irish arm of ESPAD, the largest cross-national project on adolescent substance use in the world, with the overall aim of repeatedly collecting comparable data on substance use among young people (www.espad.org). ESPAD takes place concurrently every 4 years in some 35 European countries, and is based on a common set of questions and methodology (the full questionnaire is in Supplemental File I). Students were surveyed in a stratified random sample of schools (n = 50) in Ireland, based on geographic region and stratified according to school type (secondary, vocational, community/comprehensive), religious affiliation (Roman Catholic, Church of Ireland, inter-denominational), gender (all-boys, all-girls, mixed), and school-level disadvantage status (DEIS vs non-DEIS). Data were collected between March and May 2019, and completed surveys were entered manually into SPSS v22 exactly as they appeared in the survey. Data entry was cross-checked via double entry for 20% of surveys. Full accounts of the data cleaning procedure have been reported elsewhere (ESPAD Report 2019). The total valid sample was 3495.

Measures

The outcome variable, prevalence of e-cigarette current use was measured by the question: ‘How often have you smoked e-cigarettes during the last 30 days?’ — not at all; less than once per week; at least once a week; and almost every day; recoded as ‘current use’ no vs yes.

Independent variables (socio-demographic, individual, peer and familial characteristics) are shown in detail in Table 1. Socio-demographic variables included age, gender, parental education completed, perceived family wealth, and household composition. Individual behaviours which included polysubstance use as well as potentially protective behaviours were: use of combustible cigarettes, alcohol, cannabis — including problem cannabis use [Cannabis Abuse Screening Test (CAST) (Bastiani et al. 2017)] ( a 6-item, 5-point scale, Cronbach’s alpha 0.83), inhalants, tranquilizers (with prescription); age of smoking and alcohol initiation; problems with social media use (3-item, 5-point Likert scale, Cronbach’s alpha 0.67), internet use (14-item, 5-point Likert scale, Cronbach’s alpha 0.92), online gaming (12-item, 5-point Likert scale, Cronbach’s alpha 0.95), and gambling; missing school due to illness or truancy; reading books other than school books, actively participating in sport, having other hobbies, and average school grade. Variables measuring peer risk activities were: how many of their friends smoke combustible cigarettes, drink alcoholic beverages, get drunk, smoke cannabis, take tranquilizers/sedatives, take ecstasy, and use inhalants. The variable peer support measured friends’ help, support, sharing and communication (4-item, 7-point Likert scale, Cronbach’s alpha 0.94). Familial variables measured familial support (a 4-item, 7-point Likert scale, Cronbach’s alpha 0.92), familial regulation and relationship with parents.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to calculate prevalence of current use of e-cigarettes reported by young people aged 15,16, and 17 years old. Pearson’s X2 test (for categorical variables) and Student’s t test (for continuous variables) were conducted to compare e-cigarette use among current users, with differences being analysed in relation to sociodemographic behavioural factors including (other) substance use, absenteeism, peer risk activities, and familial regulation and support (characteristics of the sample, Table 1). To assess potential multicollinearity, all variables in the study were adjusted by the dependent variable (e-cigarette ever- and current use) using Spearman’s correlation coefficient and variance inflation factor (VIF) as appropriate between variables, and a VIF < 5 was used to detect multicollinearity. A forward stepwise logistic regression analysis was used to assess potential correlates of e-cigarette use, and only variables with a p value of less than 0.7 were retained in the final model and are presented in Table 3. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and their 95% confidence intervals were estimated, and associations with a p value of < .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata version 16.

Results

Characteristics of e-cigarette current users

A total of 3495 students were included in this survey. Sample characteristics of e-cigarette use among 15–17-year-olds are shown in Table 2. 17.3% (n = 604) were current users. Compared with boys, girls were less likely to be current users (54%, n = 1558 vs 46%, n = 1326, p < .001). Current e-cigarette users and non-users differed according to gender, parental education, household composition, absenteeism, ever- and current smoking, absence from school due to illness and skipping school, ever-, current, and binge alcohol use, ever- and current cannabis use, and problem cannabis use, ever-use of tranquilizers with or without prescription, perceived risks of using e-cigarettes, peer risk activities, and familial regulation (all p < .05). E-cigarette use is higher than cigarette current use (17.3% vs 13.8%); 44.9% (n = 270) of e-cigarette current users are not current smokers, while 95% (n = 2732, p < .001) of those who are not current e-cigarette users are not current smokers either.

E-cigarette current use: multivariable analysis

Stepwise logistic regression analyses were carried out to identify significant associations with e-cigarette current use and to determine the effects of socio-demographic, individual, peer, and familial variables. Adjusted ORs (AOR) were computed. Multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 3) indicates that compared with boys, girls were significantly less likely to be e-cigarette current users (AOR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.32–0.96, p < .01). Older students were less likely to be current e-cigarette users (AOR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.17–0.67, p = < .05), as were those who perceived that their families were better off than other families (AOR = 0.29, 95% CI: 0.13–0.65, p < .01). Respondents whose parents had college or university education (reference group: completed primary or some secondary education) had significantly higher odds of reporting e-cigarette current use. This was the case for maternal higher education (AOR = 27.54, 95% CI: 1.50–505.77, p = < .05) and paternal higher education (AOR = 2.44, 95%CI: 1.00–5.91, p < .05). Household composition was not significantly associated with current use.

With regard to individual behaviours, the strongest associations with e-cigarette current use were with current smoking (AOR = 7.22, 95% CI: 3.97–13.12, p < .001), problem cannabis use (AOR = 3.12, 95% CI: 1.40–6.93, p < .01), and heavy episodic (‘binge’) drinking (AOR = 1.81, 95% CI: 1.00–3.32, p = .054). Current use of e--cigarettes was not significantly associated with ever polysubstance use. Older initiation of smoking was associated with lower odds of current e-cigarette use (AOR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.26–0.93, p < .05). Perceiving a great risk in trying e-cigarettes once or twice increased the odds by over 10 (AOR = 10.52, 95% CI: 1.25–87.98, p < .05) but perceiving a slight or moderate risk did not have a significant effect. However, the majority of current users (69.4%, n = 414) perceived no risk and only 3% (n = 18) of current users perceived a great risk. Actively participating in sports was associated with higher odds of current e-cigarette use (AOR = 2.21, 95% CI:1.05–4.65, p < .05). Academic attainment was not statistically associated.

In terms of peer risk activities, having peers who ‘get drunk’ was significantly positively associated with e-cigarette current use (AOR = 5.30, 95% CI:1.34–20.86, p < .05) whereas familial support was significantly negatively associated with current use (AOR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.64–0.95, p < .05). Neither peer support nor satisfaction with parental relationships was associated with current e-cigarette use.

Discussion

Main findings

E-cigarette use among young people in Ireland has risen dramatically and now stands at 37% ever-use and 17.3% current use (used in last 30 days). Initially, this rise occurred in tandem with a continuing trend of decreasing smoking prevalence, but latest figures for smoking in Ireland show that this decline in smoking has halted overall and, among boys, smoking has risen from 13% in 2015 (Taylor et al. 2016) to 16% in 2019 (Sunday et al. 2020). Boys are also more likely than girls to use e-cigarettes. Smoking combustible cigarettes and using e-cigarettes are risk activities that are closely aligned. Respondents in our survey who smoked were much more likely to use e-cigarettes. The apparent reversal in smoking prevalence, together with the great increase in prevalence of e-cigarette use, has implications for tobacco control policies, including, in particular, health education, regulation, and cessation services for young people (Hanafin and Clancy 2019).

Socio-demographic influences: age, gender, social class, and household composition

E-cigarette use, like smoking, is a gendered activity. Boys are now more likely to be at risk of both smoking and of e-cigarette use, and gender remains a predictor when covariates have been adjusted for. Smoking is well-established as a classed activity, but findings about e-cigarettes and social class have been ambivalent (Kapan et al. 2020). Recent Irish research found that, in a sample in which smoking was patterned by social class, e-cigarette use (ever- or current) was not (Költő et al. 2020). The prevailing consensus in the sociology of health is that higher socioeconomic status (SES) lowers illness risk (Martin 2019). Therefore, better-off families and having higher-educated parents might be expected to be protective variables but, as with other studies (Kapan et al. 2020), our findings about social class and e-cigarette use are inconsistent. When covariates were adjusted for, perceiving that one’s family was better off considerably reduced the odds of current e-cigarette use but having parents who were college/university educated increased the odds. This suggests some differences in young people’s views and motivations with regard to e-cigarettes compared with combustible cigarettes, as the association between smoking and lower socio-economic status is well-established. The association between SES and use of other addictive substances is also ambivalent. For example, young adults with the highest family background SES have been found to be most prone to alcohol and marijuana use, even after controlling for covariates (Patrick et al. 2012). They are also more likely to use other drugs, and to use alcohol and other substances to cope with stress (Martin 2019). Our findings may indicate that e-cigarette use has more in common with alcohol and other drug use than it has with smoking. Familial support was negatively associated with current use (AOR = 0.78, 95% CI: 0.64–0.95, p = .015) suggesting that, as familial support increases, the odds of being an e-cigarette current user decrease.

Individual behaviours

Polysubstance use is highly prevalent among adolescents who use e-cigarettes (Gilbert et al. 2020) and, in our study, the strongest associations with e-cigarette use were found to be with other substance use. Current use of e-cigarettes was strongly associated with current smoking and current cannabis problem use, and to a lesser extent, current heavy episodic (‘binge’) drinking.

Our initial descriptive analyses suggested that particular individual behaviours were associated with either lower e-cigarette use (being active in sports, reading books for enjoyment, having hobbies such as art and music) or more e-cigarette use (truancy, early tobacco or alcohol initiation (aged 13 years or younger), using alcohol to get high, problem or compulsive internet/social media/gambling behaviours). When we adjusted for covariates, most of the individual behaviour variables were not significantly associated, but early smoking initiation remained associated with e-cigarette current use. Actively participating in sport showed a 2.2 increased odds of e-cigarette current use pointing again to differences in how adolescents view e-cigarettes compared with combustible cigarettes, perhaps considering them a “healthier” substance.

Peer influences

Adolescents are more likely to engage in risky behaviors in the presence of peers (Gardner and Steinberg 2005; Chein et al. 2011). In our study, we report very strong correlations between all peer substance use and e-cigarette current use. However, we observe that once covariates are adjusted for, peer risk activities are largely not predictive of e-cigarette current use, with the single exception of having peers who “get drunk”.

Dependency

E-cigarette users in our survey were more likely to be current users of combustible cigarettes, to have increased odds of problem cannabis use and ‘binge’ drinking, perhaps indicating problems with substance dependency and they may, therefore, have difficulty quitting e-cigarettes (Wills et al. 2017).

We agree with others (Gilbert et al. 2020) that e-cigarette screening should include the assessment of other substances, with a view to identifying and implementing prevention efforts and improving population health.

Regulation of tobacco products

Smoking prevalence in Irish teens and adults declined significantly during the period 1995 to 2015, and Ireland’s very progressive tobacco control policies and legislation have been shown to account for a great deal of this decline (Li et al. 2018, 2020). A study estimating the impact of individual policies implemented between 1995 and 2015 on reduction of smoking prevalence in teenagers in Ireland (Li et al. 2020) examined seven tobacco control interventions: price, Smokefree legislation, health warning on packages, advertising ban, availability of cessation treatment, youth access, and mass media campaigns. For both male and female adolescents, real price increases and legislation banning smoking in workplaces were significantly associated with reductions in smoking.

Implications for regulation of e-cigarettes

Lack of full knowledge of the harms of e-cigarettes and also their potential role in smoking cessation in adults causes hesitancy in introducing regulations. Messaging might need to be more nuanced in terms of smoking cessation in adults, where e-cigarettes may have a role.

Further regulation of e-cigarettes is urgently required in Ireland in order to reduce e-cigarette use among young people and prevent the re-normalisation of tobacco products use in Irish society. The extension of existing regulation and legislation would be an expeditious approach, and there is a convincing argument for a re-framing of the paradigm about e-cigarettes. Re-framed as new tobacco products, they lend themselves to being regulated as are combustible cigarettes. Existing harm-reduction arguments in relation to e-cigarettes only have currency in relation to adult users, but they probably have none in relation to children. Indeed, e-cigarettes may come to represent another twist in the ‘safer cigarettes’ discourses that have been used by the tobacco industry for many decades (Hanafin and Clancy 2015).

If the effects of Tobacco Control interventions on e-cigarettes in young people mirrored effects on smoking, the greatest efficacy might be expected from price and taxation policies, and extension of Smokefree legislation to include use of e-cigarettes (Li et al. 2020). Price has been identified as a motivator for reduced e-cigarette use among young people (Pesko et al. 2018), with higher prices associated with reduced e-cigarette use among adolescents in the US. Current regulation of e-cigarettes in Ireland is largely confined to compliance with the EC Tobacco Products Directive 2014/40/EU (TPD) (European Parliament and Council 2014). An extension of the existing Irish Smokefree legislation to include e-cigarettes would mean that e-cigarettes would be prohibited in workplaces, enclosed public places, restaurants, bars, education facilities, healthcare facilities, and public transport. Proposed new tobacco control legislation policies by the Irish government, to include age restriction for e-cigarette purchase to over-18s, may have an impact on e-cigarette use among students, as support for tobacco control, including non-combustible products, is high (Wipfli et al. 2020).

Implications for health education and cessation

Future research surveys in adolescents should include intention and readiness to quit e-cigarettes. Health education may have a role in encouraging cessation as there is evidence from adults that learning about nicotine risk through fact sheets may lead to being motivated to re-evaluate the risks of e-cigarettes (Yang et al. 2020).

Perceiving slight or moderate risk in using e-cigarettes appears to be protective against current use, also suggesting a role for health education by providing clear, focused, up-to-date information for adolescents about the risks of e-cigarette use. It would seem that efforts could be stepped up in the junior cycle of post-primary schooling to develop health education curricula that are appropriate in terms of content, pedagogy, resources, and evaluation (Hanafin and Clancy 2019, Hanafin, Clancy, the SILNE R Partners 2020).

Conclusion

Boys are more likely than girls to be current users of e-cigarettes, as are children of college/university-educated parents; but those who perceive their family to be better off than others are less likely to be current e-cigarette users. Individual risk behaviours, particularly in terms of polysubstance use, are most relevant. Current smoking shows the highest odds of current e-cigarette use, with adjusted odds of over 7. In this sense, tobacco control remains a primary goal in protecting young people from other substance abuse.

References

Bastiani L, Potente R, Scalese M, Siciliano V, Fortunato L, Molinaro S (2017) The cannabis abuse screening test (CAST) and Its applications. In: V. R. Preedy (Ed.) Handbook of cannabis and related pathologies: biology, pharmacology, diagnosis, and treatment. Elsevier Academic Press, Cambridge, MA, pp 971–980

Best C, Haseen F, Currie D, Ozakinci G, MacKintosh AM, Stead M, Eadie D, MacGregor A, Pearce J, Amos A, Frank J (2018) Relationship between trying an electronic cigarette and subsequent cigarette experimentation in Scottish adolescents: a cohort study. Tob Control 27(4):373–378

Bozier J, Chivers EK, Chapman DG, Larcombe AN, Bastian NA, Masso-Silva JA, Byun MK, McDonald CF, Alexander LE, Ween MP (2020) The evolving landscape of e-cigarettes: a systematic review of recent evidence. Chest 157(5):1362–1390

Chein JM, Albert D, O’Brien L, Uckert K, Steinberg L (2011) Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain’s reward circuitry. Dev Sci 14(2):F1–F10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01035.x

Conner M, Grogan S, Simms-Ellis R, Flett K, Sykes-Muskett B, Cowap L, Lawton R, Armitage CJ, Meads D, Torgerson C, West R (2018) Do electronic cigarettes increase cigarette smoking in UK adolescents? Evidence from a 12-month prospective study. Tob Control 27(4):365–372

European Parliament and Council (2014) Directive 2014/40/Eu of The European Parliament And Of The Council on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/37/EC Text with EEA relevance. European Parliament, Brussels. Eur-lex.europa.eu. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=celex:32014L0040

ESPAD Report (2019) Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs. EMCDDA/ESPAD, Lisbon

Evans-Polce R, Veliz P, Boyd C, McCabe V, McCabe S (2020) Trends in E-cigarette, cigarette, cigar, and smokeless tobacco use among US adolescent cohorts, 2014–2018. Am J Public Health 110(2):163–165

Fadus MC, Smith TT, Squeglia LM (2019) The rise of e-cigarettes, pod mod devices, and JUUL among youth: factors influencing use, health implications, and downstream effects. Drug Alcohol Depend 201:85–93

Gardner M, Steinberg L (2005) Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: an experimental study. Dev Psychol 41(4):625–635. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.625

Gentzke A, Creamer M, Cullen K, Ambrose B, Willis G, Jamal A et al (2019) Vital signs: tobacco product use among middle and high school students — United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68(6):157–164

Gilbert PA, Kava CM, Afifi R (2020) High-school students rarely use E-cigarettes alone: a sociodemographic analysis of polysubstance use among adolescents in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res 23(3):505–510

Grana RA, Ling PM (2014) “Smoking revolution”: a content analysis of electronic cigarette retail websites. Am J Prev Med 46(4):395–403

Hanafin J, Clancy L, the Silne R partners (2020) Tobacco-related health education in schools in seven EU cities. Tob Prev Cessation 6(Supplement):A40. https://doi.org/10.18332/tpc/128422

Hanafin J, Clancy L (2020) A qualitative study of e-cigarette use among young people in Ireland: incentives, disincentives, and putative cessation. PLoS One 15(12):e0244203. eCollection 2020.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244203

Hanafin J, Clancy L (2015) History of tobacco production and use. In: Loddenkemper R, Kreuter M (eds) The tobacco epidemic 2015. Karger, Basel, Vol. 42, 1–18

Hanafin J, Clancy L (2019) Youth smoking in Europe. Strategies for prevention and reduction. TFRI, Dublin

Hanafin J, Sunday S, Keogan K, Clancy L (2021) Worrying changes in adolescent e-cigarette use 2014-2019: A secondary analysis of five Irish health datasets. Ir J Med Sci 190(Suppl 1, S 31):S57–S58

Huang J, Duan Z, Kwok J, Binns S, Vera L, Kim Y et al (2018) Vaping versus JUULing: how the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette market. Tob Control 28(2):146–151

Kapan A, Stefanac S, Sandner I, Haider S, Grabovac I, Dorner T (2020) Use of electronic cigarettes in European populations: a narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(6):1971

Kinnunen J, Rimpelä A, Lindfors P, Clancy L, Alves J, Hoffmann L et al (2020) Electronic cigarette use among 14- to 17-year-olds in Europe. Eur J Public Health 31(2):402–408. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa145

Költő A, Gavin A, Molcho M, Kelly C, Walker L, Nic Gabhainn S (2020) The Irish Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Study 2018. Department of Health & Health Promotion Research Centre, National University of Ireland, Dublin & Galway

Li S, Keogan S, Clancy L (2020) Does smoke-free legislation work for teens too? A logistic regression analysis of smoking prevalence and gender among 16 years old in Ireland, using the 1995–2015 ESPAD school surveys. BMJ Open 10(8):e032630

Li S, Levy D, Clancy L (2018) Tobacco Free Ireland 2025: SimSmoke prediction for the end game. Tob Prev Cessat 4:23

Martin CC (2019 May 12) High socioeconomic status predicts substance use and alcohol consumption in US undergraduates. Substance Use & Misuse 54(6):1035–1043

McCarthy A, Lee C, O’Brien D, Long J (2020) Harms and benefits of e-cigarettes and heat-not-burn tobacco products: a literature map. Health Research Board, Dublin. Available from: https://www.hrb.ie/fileadmin/2._Plugin_related_files/Publications/2020_publication-related_files/2020_HIE/Evidence_Centre/Harms_and_benefits_of_e-cigarettes_and_heat-not-burn_tobacco_products_Literature_map.pdf

Overbeek DL, Kass AP, Chiel LE, Boyer EW, Casey AM (2020 Jul 2) A review of toxic effects of electronic cigarettes/vaping in adolescents and young adults. Crit Rev Toxicol 50(6):531–538

Patrick ME, Wightman P, Schoeni RF, Schulenberg JE (2012 Sep) Socioeconomic status and substance use among young adults: a comparison across constructs and drugs. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 73(5):772–782

Pesko MF, Huang J, Johnston LD, Chaloupka FJ (2018) E-cigarette price sensitivity among middle-and high-school students: evidence from monitoring the future. Addiction 113(5):896–906

Scottish Government (2019) Scottish Schools Adolescent Lifestyle and Substance Use Survey (SALSUS) 2018 Smoking Report. Scottish Government, Edinburgh [cited 9 July 2020]. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/statistics/2019/11/scottish-schools-adolescent-lifestyle-substance-use-survey-salsus-smoking-report-2018/documents/scottish-schools-adolescent-lifestyle-substance-use-survey-salsus-smoking-report-2018/scottish-schools-adolescent-lifestyle-substance-use-survey-salsus-smoking-report-2018/govscot%3Adocument/scottish-schools-adolescent-lifestyle-substance-use-survey-salsus-smoking-report-2018.pdf

NHS (2019) Smoking, Drinking and Drug Use among Young People in England 2018 [NS]. NHS Digital, Leeds, UK. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/smoking-drinking-and-drug-use-among-young-people-in-england/2018

Sunday S, Keogan S, Hanafin J, Clancy L (2020) ESPAD 2019 Ireland: results from the European Schools Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs in Ireland. TFRI, Dublin. Available from: www.tri.ie

U.S. Surgeon General (2018) Surgeon General’s advisory on e-cigarette use among youth. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, Washington, DC. Available from: https://e-cigarettes.surgeongeneral.gov/documents/surgeon-generals-advisory-on-e-cigarette-use-among-youth-2018.pdf

Taylor K, Babineau K, Keogan S, Whelan E, Clancy L (2016) ESPAD 2015. European schools project on Alcohol & Other Drugs in Ireland. TFRI, Dublin.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2016) E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta, GA

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2014) The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta, GA

Wills T, Sargent J, Gibbons F, Pagano I, Schweitzer R (2017) E-cigarette use is differentially related to smoking onset among lower risk adolescents. Tob Control 26(5):534–539

Wipfli H, Bhuiyan MR, Qin X, Gainullina Y, Palaganas E, Jimba M, Saito J, Ernstrom K, Raman R, Withers M (2020) Tobacco use and E-cigarette regulation: perspectives of university students in the Asia-Pacific. Addict Behav 106420

Yang B, Owusu D, Popova L (2020) Effects of a nicotine fact sheet on perceived risk of nicotine and e-cigarettes and intentions to seek information about and use e-cigarettes. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(1):131

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium. Funding was obtained from the Royal City of Dublin Hospital Trust (RCDHT) Grant no.184 and from the Dept. of Health Ireland ESPAD Tender 2019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Joan Hanafin and Luke Clancy conceptualized the structure, and agreed the methodology and the content of the study, Salome Sunday did the initial analysis, and Joan Hanafin wrote the initial version of the MS; all authors contributed to the development of the MS and read and approved of the final version. Luke Clancy acquired the funding and was responsible for resources and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest declared by any of the authors.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics and integrity Committee of the TU Dublin REC-18-26.

Informed consent

Parent/guardian information sheet and school information sheets were distributed. Parent non-consent forms were distributed to each student.

No individual data or image is published.

Data available from author on request.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanafin, J., Sunday, S. & Clancy, L. E-cigarettes and smoking in Irish teens: a logistic regression analysis of current (past 30-day) use of e-cigarettes. J Public Health (Berl.) 31, 955–966 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01610-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01610-1