Abstract

Aim

This study reviews the empirical evidence on care delivery in complex emergencies (CEs) to better understand ways of improving care delivery and mitigating inequity in care among refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) in CEs.

Subject and methods

A systematic search was conducted in Web of Science, MEDLINE, PubMed and Embase. A manual search was conducted in the WHO Global Index Medicus and Google Scholar. Peer-reviewed English-language publications that reported results on care delivery in CEs were included for review. There was no limitation on the year or the geographical location of the studies. The content of the publications was qualitatively analysed, and the results are thematically presented in tabular form.

Results

Thirty publications were identified. Information regarding coverage, accessibility, quality, continuity and comprehensiveness of care service delivery was extracted and synthesized. Findings showed that constant insecurity, funding, language barriers and gender differences were factors impeding access to and coverage and comprehensiveness of care delivery in CEs. The review also showed a preference for traditional treatment among some refugees and IDPs.

Conclusion

Evidence from this systematic review revealed a high level of unmet healthcare need among refugees and IDPs and the need for a paradigm shift in the approach to care delivery in CEs. We recommend further research aimed at a more critical evaluation of care delivery in CEs with a view to providing a more innovative and context-specific care service delivery in these settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

A complex emergency (CE) is defined as a “humanitarian situation characterized by political instability, violent conflict, large population displacements, food shortages, social disruption and collapse of public health infrastructure” (IASC 1994). Care delivery in CEs is multidimensional and challenging (Pottie 2015). Poor and unsanitary living conditions, along with low access to healthcare caused by overstretched and sometimes non-functional healthcare systems on the one hand, and funding and/or mandate constraints for aid agencies on the other hand, exacerbate the inadequacy and inequity in care delivery in CEs (Hansch and Burkeholder 1996; Olu et al. 2015; Sondorp et al. 2001).

In recent years, an increasing number of CEs are occurring, resulting in some 68.5 million refugees and internally displaced persons around the globe (UNHCR 2018). Against this backdrop, healthcare delivery in CEs is becoming overwhelming for stakeholders in those contexts. This raises the question of access to and quality of care for refugees and other forcibly displaced people who are caught up in CEs (Brennan and Nandy 2001; Nickerson et al. 2015).

In the literature, the lack of access to and the inadequacy of care delivery are consistently emphasized as factors responsible for inequity in care delivery in CEs (Adaku et al. 2016; Casey et al. 2015; MacDuff et al. 2011; Murphy et al. 2017). Bloland and Holly (2003) argue that “historically, those involved with care delivery in CEs have given little attention to the socio-cultural dimensions or to the wider global context within which CEs develop”. In resource-poor environments typical of such contexts, there is also the question of providing tailor-made culturally appropriate care for victims (Bloland and Holly 2003).

The World Health Organization’s Traditional Medicine (WHO-TM) Strategy 2014–2023 has recently become the basis for an increasingly popular argument in favor of traditional and alternative medicine (TAM) as a useful complement to the usual biomedical approach to care service delivery in CEs (Oyabode et al. 2016; WHO 2013). However, it is not known to what extent traditional care is accepted among the populations affected by CEs, nor is it clear whether this could be a useful strategy to mitigate inequity in care delivery among a population affected by CE (MacDuff et al. 2011).

In order to address care delivery inequity in the context of CE, an understanding of the major fundamental elements that create such inequity is necessary. One of the first steps is to review existing evidence on the various methods of care delivery in CEs However, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no systematic review of the overall care delivery in CEs, apart from the annual Global Emergency Medicine Literature Review (GEMLR). The GEMLR conducts an annual search of relevant peer-reviewed and grey literature articles in emergency medicine in order “to identify, review, and disseminate the most important new research in this field to a worldwide audience of academics and clinical practitioners” (Becker et al. 2018; Jacquet et al. 2013).

The purpose of this study is to systematically review the empirical evidence on care delivery in CEs. It aims to provide a bird’s-eye view of the entire care delivery in these settings to form a basis for understanding the relevance of TAM to care delivery in such contexts. The study may help guide policymakers in designing more all-inclusive, efficient, tailor-made care delivery approaches that minimize inequity in CEs. In terms of research implications, the study identifies areas for future research and also contributes to the literature on inequity in care delivery in CEs.

Methods

Search strategy

The literature review is based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework (Moher et al. 2015). The search was conducted between late October and early November 2018 in Web of Science, MEDLINE, PubMed and Embase (Ovid). In October 2019, we once again screened the databases for any relevant publications in the past 12 months. Manual searches were also conducted in the WHO Global Index Medicus and Google Scholar libraries for grey articles and publications that were not indexed in established academic journals.

Three thematic keyword blocks, namely, intervention, population and context, were chosen to facilitate the search. Combinations of different synonyms of the keywords were used. Provisions were made for differences in spelling. Truncation functions were used to allow for the inclusion of all possible variations of identified words. This resulted in the following chain of keywords used for the search:

(Healthcare OR care delivery OR medicare OR medical intervention OR traditional medicine OR traditional healer OR health equity) AND (refugee OR internally displaced persons) AND (complex emergency OR conflict OR war)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were determined using the relevant elements of the population, intervention, comparison (PIC) concept for qualitative studies (Stern et al. 2014). Publications were included if the study population was a forcibly displaced population such as refugees or internally displaced persons, intervention consisted of all aspects of care delivery, and the context of interest was CE environments. Only English-language publications were included, but there was no limitation with regard to geographical location or year of publication. A librarian was contacted to review the search criteria.

Publications were excluded if they did not report results on a care-related topic, did not relate to a CE, had a target population of undocumented migrants or asylum seekers, were duplicates of already included publications, were non-empirical or were review papers.

Screening process

The screening process consisted of three steps. First, relevant publications were selected based on title and abstract. Publications that remained after the first screening step were downloaded and checked for relevance based on their full text. Publications that could not be downloaded were excluded. The reference lists of publications that remained after the second screening step were checked for additional relevant publications. This formed the third screening step. The selection was carried out by a member of the research team. The intermediate and final results were discussed with the other researchers in the team.

Method of analysis

All retained publications were thoroughly read and evaluated. To assess the quality of the papers reviewed, scores (low, moderate or high) were assigned based on representativeness of sample size and generalizability of study results (Table 2), bearing in mind how representative the data were for the specific refugee context or how representative the results were for refugee contexts in general. The quality of our review was assessed in line with the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al. 2015), see Appendix C. Publications were analysed using the directed qualitative content analysis technique (thematic analysis). This approach specifically allows data to be arranged thematically and thus “helps to systematically and objectively describe the study phenomenon” (Hsieh and Shannon 2005). The World Health Organization’s (WHO) key indicators for measuring efficient care service delivery, namely, coverage of the intervention, and accessibility, quality of care, continuity and comprehensiveness of service delivery (WHO 2010), were used as the themes for analysis of the evidence. Information relating to these themes was extracted from the publications and synthesized using a classification matrix. Each theme was scored as low, moderate or high (Appendix Table 3–7). The score was assigned according to the reported effects of the respective intervention on the target population or the target population’s perception of the intervention. The presentation of the results indicates whether a finding is confirmed by several sources or only a single source. We performed a qualitative data synthesis, and the results are presented in tabular form, accompanied by a formal narrative synthesis.

Results

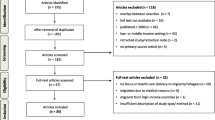

The initial search yielded a total of 2939 publications, of which 2787 were excluded because they were either duplicates, unrelated, reviewed other studies, or could not be downloaded. This left us with 152 publications. After reviewing their titles and abstracts, we excluded another 120 publications, leaving us with 32 publications. The full text of the 32 articles was read in detail, which led to the exclusion of another eight articles for not fully meeting the inclusion criteria. Six additional papers were identified from the reference lists of included articles. This left us with a total of 30 articles which were included for analysis.. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the detailed search procedure.

Selected publications were divided into five categories based on the WHO Global Health Observatory (GHO) theme. We considered these five categories to be the essential health services in refugee situations. Category 1 includes studies that relate to sexual and reproductive health, while category 2 include studies on non-communicable diseases. Categories 3 and 4 relate to infectious diseases and mental and psychosocial health, respectively. Category 5 is an omnibus category containing topics such as outbreak preparedness, malnutrition, and surgery and disability care in CEs.

As indicated in Figure 1, in category 1 (sexual and reproductive health) we have 11 papers, in category 2 (non-communicable diseases) we have 4 papers, in category 3 (mental health) we have 3 papers while we have 3 and 9 papers for category 4 (Infectious diseases) and category 5 (others) respectively.

Overall characteristics and quality of the reviewed publications

The overall characteristics of the reviewed publications are presented in Tables 1 and 2. All publications were empirical studies published in peer-reviewed journals between 2003 and 2018. Thirteen of the publications were from East Africa, followed by the Middle East with four publications. There were three publications from Greece, albeit with refugees from different parts of the globe. Finally, one and six publications reported results from West Africa and from multiple countries, respectively.

All studies were carried out in resource-limited refugee contexts. All publications related to different types of care delivery to refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) affected by CE resulting from protracted war or conflicts in their home countries. Overall, the topics were quite heterogenous both within and across the categories.

There were 30 publications in total. Nine studies reported results from two or more countries. Results from Kenya and Greece were reported by three studies each; results from South Sudan, Lebanon, Sudan, Jordan and Tanzania were each reported by two studies, and results from Uganda, Ethiopia, Somalia, Guinea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo were each reported by one study. Various study designs and analysis techniques were used: 14 quantitative, eight qualitative and eight mixed-methods designs. Each of the studies reported an empirical analysis on a form of care delivery in CEs. Most of the publications reported on data collected by healthcare aid organizations in refugee camps, with their health facilities as the research settings.

The internal validity, external validity and reliability of each study were scored as low, moderate or high. Overall, as shown in Table 2, there were 23, 6 studies and 1 study with high, moderate and low internal validity, respectively. For external validity, there were 17, 9 and 4 studies with high, moderate and low external validity, respectively. With regard to reliability, there were 18, 10 and 2 studies with high, moderate and low scores, respectively.

Sexual and reproductive health

A detailed assessment of sexual and reproductive healthcare use in CEs is presented in Appendix Table 3. The research objectives of the publications centred on three major themes, namely, sexual and reproductive health education, neonatal and maternal mortality, and the unmet need for family planning and post-abortion care (PAC) interventions in refugee situations.

Seven of the publications in this category reported high coverage of the various sexual and reproductive health interventions. Two publications reported moderate coverage, while the other two reported low coverage. Insufficient resources, inadequate facilities or exclusion of some patients were reported as the reasons for the less than high coverage.

Low scores in comprehensiveness and coverage were reported in the provision of general sexual and reproductive healthcare service delivery to disabled refugees and in neonatal care among refugees. Low accessibility to reproductive anatomy awareness, family planning and sexually transmitted infection care was reported for refugees with disabilities.

High quality of care was reported in the area of contraception, family planning and sexually transmitted infections, major obstetrics interventions and prevention of maternal mortality. However, continuity of delivery of these services might be a concern, as about 90% of the publications did not discuss it.

Seven publications reported that care-seeking behaviours of refugee women regarding contraception, sexually transmitted infections, maternal and newborn care, unintended pregnancies and PAC were significantly impacted by the women’s cultural and traditional beliefs. Resistance to the conventional type of newborn care was reported among refugee and host community women in South Sudan, even though it increased maternal mortality among this population. Similarly, Syrian refugee women in Lebanon reportedly maintained the same pregnancy and contraception behaviours as they had prior to displacement. Over-recourse to caesarean section was found. Indeed, some displaced Sudanese women were reported to strongly prefer traditional maternal practices and home delivery due to fear of medical doctors and surgical interventions. Nonetheless, the engagement of temporary health workers combined with the involvement of key religious and secular leaders was reported to increase the coverage and accessibility of PAC in Yemen, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Somalia. Evidence also showed the need for task sharing in care service delivery in CEs.

Non-communicable diseases (NCD)

Appendix Table 4 presents in detail the key findings of publications in category 2 focused on non-communicable diseases. Of the four publications in this category, two related to care, self-management, education and support for diabetes mellitus, while the others included other chronic diseases such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease and chronic respiratory diseases.

Two publications reported low accessibility and two reported high accessibility for diabetes and chronic disease care. Except for the continuity of the intervention, which was not discussed, all indicators were reported high for diabetes self-management education and support service delivery. There was low accessibility to care and low probability of continuity, but moderate coverage and comprehensiveness of care for disabilities and chronic diseases among refugees.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, patients with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) relied more on traditional healers for treatment and perceived traditional medicines as more effective than occidental drugs. In Jordan, refugees suffering from non-communicable diseases were entitled to the same care as uninsured Jordanians, meaning they had to pay a certain part of the cost of treatment. As a result, a significant number of refugees could not afford care. The effect of diabetes self-management education was also reported to be crucial to the survival of diabetes patients in a CE. It was thus concluded that diabetes care should be prioritized among CE-affected populations.

Mental health

As shown in Appendix Table 5, the three studies in this category reported divergent results on mental healthcare. In the case of support for neuropsychiatric disorders and mental conditions associated with stress, the coverage, accessibility and quality of care were reported to be high. The rate of visits related to emotional problems and substance use was reported to be high, and the comprehensiveness of the care system was moderate. Regarding mental health capacity building in refugee primary healthcare settings, evidence likewise showed that the use of non-specialized staff in a complex humanitarian setting was feasible and led to increased competency in care providers and better quality of care service delivery. However, one of the publications reported low coverage, low accessibility and low comprehensiveness of general psychosocial support. The lack of privacy and space in health facilities was reported to impede the quality of psychosocial support to patients.

Two publications reported that refugees with mental health needs were likely to first seek care from family members and traditional and religious healers before seeking professional help. All the publications suggested the need for context-specific psychosocial support interventions as an integral part of refugee care delivery systems.

Infectious diseases

Appendix Table 6 presents the key findings of publications in category 4 focused on infectious diseases. All three publications in this category were set in the Horn of Africa and reported results on sleeping sickness, sexually transmitted infections, HIV and tuberculosis interventions. Though quality and comprehensiveness of care were reported to be either moderate or high, accessibility was reported to be low for both sleeping sickness and HIV interventions. Tuberculosis treatment was the only intervention reported to have a high probability of continuing. Constant insecurity was reported to have a negative impact on accessibility and comprehensiveness of care. In such instances, care interventions were carried out remotely from safer locations. Donor pressure to contain costs was also reported to create governance and operational challenges, resulting in reduced refugee equitable access to care.

Other forms of care service delivery

Appendix Table 7 highlights the results of the nine publications in category 5. This category is related to other forms of care service delivery. The studies reported results on themes including the assessment and perceptions of stakeholders and patients of the quality of care delivery, disease outbreak preparedness, paediatric surgical care, dental and oral care, malnutrition and caring for refugees with childhood disabilities.

Regarding paediatric surgical care, except for continuity of care, which was not discussed, all indicators were reported to be high. On the other hand, dental care was reported to have moderate coverage and moderate probability of continuing the intervention. The low accessibility reported was attributed to a very high fee (by refugees standards) of $3 charged per consultation.

The studies that reported results on the assessment of care delivery and outbreak preparedness reported low accessibility, low comprehensiveness of care or both. Dental care and care for those with disabilities were reported to be on the back burner of healthcare provision in refugee settings. This was evident in Tanzania, where a $3 fee was charged per dental care consultation, resulting in significantly reduced access to dental care, as a considerable number of patients could not afford the “enormous” cost of the treatment. Our review also showed that other factors such as language barriers and gender differences between refugees and healthcare providers, and the lack of privacy and space in clinics, impeded the quality of and access to care service delivery. Healthcare and social work providers who spoke the language of the patients were frequently reported to face fewer challenges and were better able to provide care than providers working with interpreters.

The study on caring for children with disabilities demonstrated how the healthcare needs of children with disabilities and their carers were not being met by either community social support systems or humanitarian aid interventions, and how this resulted in persons seeking treatment for disabilities from traditional healers. One study that reported results on refugee perceptions of quality of healthcare in a CE found a situation wherein traditional healers often referred patients to the health facilities. In line with this approach, two publications suggested a culturally sensitive and context-specific care delivery approach in the CE context.

Discussion

The increase in the occurrence of CEs around the world has led to an explosion in the number of refugees and IDPs, which in turn has significantly increased the burden of care delivery by aid organizations and other stakeholders working in these contexts (WHO 2018; UNHCR 2018). The results of this review highlight the high levels of unmet healthcare need among populations affected by CEs. While funding was found to be a major determinant in the comprehensiveness, coverage and quality of care delivery in CEs (Elliot et al. 2018), cultural beliefs and previous health practices among refugees and IDPs significantly influenced their health-seeking behaviours and, by extension, accessibility of care delivery (Doocy et al. 2013, 2015; Rutta et al. 2005; Tanabe et al. 2015).

Evidence showed a resistance to conventional medicine and a preference for traditional treatment among some beneficiaries. This was reported in various cases when refugees in need of mental health or maternal care and those with NCDs were likely to first seek care from family members or traditional and religious healers before seeking professional help, even though they were aware of such services (Kane et al. 2014). This was born out of the belief that traditional medicines were more effective than occidental drugs, but also from fear of medical doctors and surgical interventions (Adam 2015; Murphy et al. 2017; Sami et al. 2018). The reasons for such attitudes may not be unreasonable. Prior to displacement, some of these people, especially those from rural sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), had lived in very remote and resource-poor environments all their lives, and as such may have developed different coping mechanisms based purely on traditional ways of life, which include a strong affinity for symbiotic family relationships and the use of traditional medicines. In the same vein, making use of non-specialized medical staff and the involvement of religious and community leaders significantly increased accessibility, coverage and quality of care service delivery (Echeverri et al. 2018; Gallagher et al. 2019). Although better funding may improve the quality, comprehensiveness and coverage of care delivery, optimal care delivery may not be achieved in a CE unless a culturally sensitive care system is in place.

Another factor impeding access to care was the cost of care. On the supply side, evidence showed donor pressure on operators to contain costs, which created governance and operational challenges resulting in reduced equitable access to care. On the demand side, however, evidence showed that it was difficult for refugees and IDPs to pay for care, no matter how meagre. Because refugees and IDPs are not entirely isolated from their host communities, care service delivery should be designed to accommodate these two sets of populations in order to mitigate disease spread and care inequity. This is particularly important in areas with a high prevalence of infectious diseases (Doocy et al. 2015; Palmer et al. 2017; Roucka 2011).

We noted that the beneficiaries were reportedly very often satisfied with the quality of care received. However, this could be in relative terms and not necessarily because the care they received was of high quality. In other words, the satisfactory rating could be because most of the beneficiaries live in resource-poor environments and may have experienced either substandard or no formal care attention all of their lives, and thus had no proper benchmark for comparison. Evidence also indicated that access to and comprehensiveness of care were restricted by constant insecurity in CEs. At such times, care delivery could only be carried out remotely from safer and sometimes more distant locations (Liddle et al. 2013). Given that such insecurity is a characteristic of CEs, it is important that alternative strategies are put in place by designating an “on-the-ground team” to carry on delivering care to beneficiaries. If well co-opted, traditional caregivers could provide one of these alternatives. Thus, morbidity and mortality among beneficiaries could be reduced during periods of insecurity.

Some specialized services such as dental, orthopaedics, and paediatric and general surgery that should be an integral part of healthcare delivery in a CE were rarely available (Hermans et al. 2017; Roucka 2011; Trudeau et al. 2015). Indeed, given the volatile nature of CEs, these specialized healthcare services are as important and as necessary as other general care services. While our review did not identify specific reasons for the short supply of these services, it is not unreasonable to suspect that inadequate funding and the lack of specialized medical practitioners were contributing factors. The negative impact of limited access to this specialized healthcare by patients was severe. They were either given palliative care or were left unattended (Hermans et al. 2017; Roucka 2011). The possibility for continued care delivery was not discussed in the majority of the publications. This may be due to the notion that refugee and IDP camps are meant to be temporary in nature. However, many camps have become long-stay and have existed for more than a decade, with no clear sign of any resolution of the conflicts that initiated the mass movement. The unpredictability of a CE context in terms of possible duration of events and the size of the affected population coupled with lack of adequate funding, which seemed the norm rather the exception, made long-term healthcare planning very complicated if not impossible (Hémono et al. 2018; Hermans et al. 2017).

Other points of discussion are the language- and gender-related barriers, both of which had negative effects on quality of care in a CE. Language and gender differences between healthcare providers and refugees were sometimes substantial. Healthcare providers faced difficulties in providing quality care if they did not speak the language of the patients and had to engage the services of interpreters. It was especially challenging in cases involving psychosocial support, where patients may have been reluctant to divulge vital but useful information that could aid in proper prognosis of their condition, if they had to communicate through a third party (Hémono et al. 2018).

Limitations

This systematic review was not without limitations. Although the literature search was systematic and explored all related studies within the scope of the review, it is possible that some relevant publications were missed during initial filtering. It was surprising that no study on malaria was found, given that malaria is endemic in rural SSA and some parts of Asia, where most of the refugee camps were situated. It may be that this topic has not been studied in the context of CEs, or it could be due to the exclusion of non-English-language journals and publications other than peer-reviewed studies, which meant that relevant grey literature such as reports and academic theses were left out. Another limitation was the selection process, which was performed by a single researcher, even though the output and any questions were discussed at each search with the project team. Thus, selection bias may not have been completely excluded. Also, the heterogeneity of the study topics and design techniques makes the comparison of findings challenging.

Conclusion

This review has focused on outlining the available evidence on care delivery in CEs. The results show that limited funding, security restrictions and exclusion of some groups of patients were factors reported as hindering access and coverage of care service delivery in CEs. Our findings also show that cultural beliefs, language barriers and gender differences between refugees and healthcare workers frequently impeded quality of care delivery in CEs. Cultural beliefs and practices were quite evidently often ignored in these settings. Many of the studies reviewed indicated that the design of culturally sensitive and context-specific medical interventions should be a routine element in refugee assistance programmes. Given all these facts, and considering the remoteness and resource-austere nature of most CEs, it may be counterproductive to put the burden of care delivery in CEs solely on aid agencies. So far, evidence has not shown otherwise. However, strands of studies have documented the belief in and patronage of traditional caregivers among some refugees in CEs, especially in SSA (Kane et al. 2014; Murphy et al. 2017; Rutta et al. 2005). Meanwhile, the WHO-TM Strategy 2014–2023 is also making a case for TAM as a complement to a biomedical approach to care delivery. Therefore, it may be advantageous to make use of traditional caregivers and healthcare professionals as well, especially in CEs occurring in SSA. Such a decision could be significant in a number of ways. On the one hand, it could be a tool for overcoming the cultural and language barriers acting as impediments to quality of and access to service delivery to beneficiaries. Aid organizations and those charged with care delivery in CEs could thereby put limited resources to optimal use, increasing coverage and comprehensiveness of care delivery that was hindered by inadequate funding. On the other hand, for those patients who were reluctant towards occidental care, it would reduce, if not eliminate, the scepticism of such beneficiaries by boosting their confidence and increasing the acceptance of the care systems in CEs. This would in turn increase accessibility to care, reduce inequity and, by extension, reduce morbidity and mortality among populations affected by CEs.

As shown in this systematic review, the complexity, peculiarity and resource poorness of the CE contexts call for a paradigm shift in the modus operandi of care delivery to refugees and IDPs. Greater creativity and innovation are needed for effective care service delivery in CE settings. Evidence has shown some form of interaction between medical professionals and traditional caregivers in terms of patient referrals by the latter to medical facilities. And based on the results of our systematic review, traditional care enjoys some acceptance within the refugee and IDP communities, especially in SSA. However, it would be incorrect to conclude that traditional care may indeed be used as a strategy to mitigate the unmet need, especially in the area of accessibility and other non-medical care needs such as health promotion and community mobilization. The available evidence thus far is insufficient and cannot be used as the basis for advocating collaboration between traditional caregivers and medical professionals. For such collaboration to be strongly advocated, further research aimed at a critical evaluation of care delivery in CEs with a view to providing more innovative and context-specific care service delivery is needed. The synergy between professional medical practitioners and traditional caregivers in CEs may not be a one-size-fits-all model. Furthermore, stakeholders must understand the areas and the modus operandi of such complementarity to be able to design and implement all-inclusive and context-specific care delivery in a CE. So far, there is insufficient evidence to recommend traditional care as a strategy for care delivery in CEs.

Abbreviations

- SRH:

-

Sexual and reproductive health

- NCD:

-

Non-communicable disease

- IF:

-

Infectious disease

- MH:

-

Mental health

- PAC:

-

Post-abortion care

References

Adaku A, Okello J, Lowry B, Kane JC, Alderman S, Musisi S, Tol WA (2016) Mental health and psychosocial support for South Sudanese refugees in northern Uganda: a needs and resource assessment. J Confl Health 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-016-0085-6

Bader F, Sinha R, Leigh J, Goyal N, Andrews A, Valeeva N, Sirios A, Doocy S (2009) Psychosocial health in displaced Iraqi care seekers in non-governmental organization in Amman, Jordan: an unmet need. J Prehosp Dis Med 24(4):312–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X00007032

Balinska M, Nesbitt R, Ghantous Z, Ciglenecki I, Staderini N (2019) Reproductive health in humanitarian settings in Lebanon and Iraq: results from four cross-sectional studies 2014-2015 Lebanon and Iraq. J Confl Health 13(24):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-019-0210-4

Becker TK, Trehan I, Hayward AS, Hexom BJ, Kivlehan SM, Lunney KM, Levine A, Modi P, Osei-Ampofo M, Pousson A, Cho DK, (2018) Global Emergency Medicine: A review of the literature from 2017. Soc Acad Emerg Med 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13456

Bloland PB, Holly WA (2003) Community involvement in malaria prevention. In: Malaria control during mass population movements. The National Academies Press, Washington DC, pp 93–102

Brennan R, Nandy R (2001) Complex humanitarian emergencies: a major global health challenge. J Emerg Med 13:147–156

Casey S, Chynoweth S, Cornier N, Gallagher M, Wheeler E (2015) Progress and gaps in reproductive health in three humanitarian settings: mixed-methods case studies. J Confl Health 9:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-9-S1-S3

Chen M, von Roenne A, Souare Y, von Roenne F, Ekirapa A, Hpward N, Borchert M (2008) Reproductive health for refugees by refugees in Guinea II: sexually transmitted infections. J of Confl Health 2(14):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-2-14

Cherri Z, Cuesta J, Rodriguez-Llanes J, Guha-Sapir D (2017) Early marriage and barriers to contraception among Syrian refugee women in Lebanon: a qualitative study. Intl J Env Res and Pub Health 14(836):1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080836

Doocy S, Sirois A, Tileva M, Storey J, Burnham G (2013) Chronic disease and disability among Iraqi populations displaced in Jordan and Syria. Intl J Health Plan Mgt 28:e1–e12. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2119

Doocy S, Lyles E, Roberton T, Akhu-Zaheya L, Oweis A, Burnham G (2015) Prevalence and care-seeking for chronic diseases among Syrian refugees in Jordan. BMC Pub Health 15:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2429-3

Echeverri C, Le Roy J, Worku B, Ventevogel P (2018) Mental health capacity building in refugee primary healthcare settings in sub-Saharan Africa: impact, challenges and gaps. J Glob Ment Health 5(e28):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2018.19

Elliott J, Das D, Cavailler P, Schneider F, Shah M, Ravaud A, Boulle P et al (2018) A cross-sectional assessment of diabetes self-management, eduaction and support needs of Syrian refugees in Bekaa Valley, Lebanon. J Confl Health 12(40):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-018-0174-9

Gallagher M, Morris C, Aldogani M, Eldred C, Shire AH, Managhan E, Ashraf S, Meyers J, Amsalu R (2019) Postabortion Care in Humanitarian Emergencies: improving treatment and reducing recurrence. Glob Health Sci Pract 7(2):231–246. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-18-00400

Hansch S, Burkholder B (1996) When chaos reigns. Harvard International Review. https://web-b-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.ub.unimaas.nl/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=ec1a8fda-d9bc-46d3-a170-7c6a87b290a4%40sessionmgr103&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#AN=9709080254&db=bth. Accessed 3 May 2019

Hémono R, Relyea B, Scott J, Khaddaj S, Douka A, Wringe A (2018) "the needs have clearly evolved as time has gone on": a qualitative study to explore stakeholders' perspectives on the health needs of Syrian refugees in Greece following the 2016 European Union-Turkey agreement. J Confl Health 12(24):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-018-0158-9

Hermans M, Kooistra J, Cannegieter S, Rosendaal F, Mook-Kanamori D, Nemeth B (2017) Healthcare and disease burden among refugees in long-stay refugee camps at Lesbos, Greece. Eur J Epi 32:851–854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-017-0269-4

Holt B, Effler P, Brady W, Friday J, Belay E, Parker K, Toole M (2003) Planning STI/HIV prevention among refugees and mobile populations: situation assessment of Sudanese refugees. Intl J Dis 27(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7717.00216

Hsieh H, Shannon S (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. J qual health res 15(9):1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Hynes M, Sakani O, Spiegel P, Cornier N (2012) A study of refugee maternal mortality in 10 countries, 2008 - 2010. Intl Persp Sex Repro Health 38(4):205–213. https://doi.org/10.1363/3820512

IASC (1994) Definition of complex emergency. Inter-Agency Standing Committee. www.interagencystandingcommittee.org/content/definition-complex-emergency. Accessed on 07 March 2018,

Jacquet G, Foran M, Bartels S, Becker T, Schroeder E, Duber H, Levine A (2013) Global emergency medicine: a review of the literature from 2012. Academic Emerg Med 20(8):834–843. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12173

Kane J, Ventevogel P, Spiegel P, Bass J, van Ommeren M, Tol W (2014) Mental, neurological, and substance use problems among refugees in primary healthcare: analysis of the health information system in 90 refugee camps. J Med Glob Health 12(228):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0228-9

Kim G, Torbay R, Lawry L (2007) Basic health, women's health, and mental health among internally displaced persons in Nyala province, south Dafur. Amer J Pub Health 97(2):353–361

Liddle K, Elema R, Thi S, Greig J, Venis S (2013) Tuberculosis treatment in a chronic complex emergency: treatment outcomes and experiences in Somalia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 107:690–698. https://doi.org/10.1093/trstmh/trt090

MacDuff S, Grodin M, Gardiner P (2011) The use of complementary and alternative medicine among refugees: a systematic review. J Immigrant Minority Health 13:585–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-010-9318-8

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticre M, Shekelle P (2015) Stewart LA (2015) preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews 4:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Murphy A, Biringanine M, Roberts B, Stringer B, Perel P, Jobanputra K (2017) Diabetes care in a complex humanitarian emergency setting: a qualitative evaluation. Health Serv Res 17:431–440. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2362-5

Nickerson J, Hatcher-Roberts J, Adams O, Attaran A, Tugwel P (2015) Assessments of health services availability in humanitarian emergencies: a review of assessments in Haiti and Sudan using a health systems approach. J Confl and Health 9:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-015-0045-6

Odero W, Otieno-Nyunya B (2001) Major obstetric interventions among encamped refugees and the local population in Turkana District, Kenya. EA Med J 78(12):666–672

Olu O, Usman A, Woldetsadik S, Chamla D, Walker O (2015) Lessons learnt from coordinating emergency health response during humanitarian crises: a case study implementation of health cluster in northen Uganda. J Confl Health 9(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-9-1

Oyabode O, Kandala N, Chilton P, Lilford R (2016) Use of traditional medicine in middle-income countries: WHO-SAGE study. J Health Pol Plan 31:984–991. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw022

Palmer J, Robert O, Kansiime F (2017) Including refugees in disease elimination: challenges observed from a sleeping sickness programme in Uganda. J Confl Health 11(22):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-017-0125-x

Polonsky J, Ronsse A, Ciglenecki I, Rull M, Porten K (2013) High levels of mortality, malnutrition, and measles among recently displaced Somali refugees in Dagahaley camp, Dadaab refugee camp complex, Kenya, 2011. J Confl Health 7(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1505-7-1

Pottie K (2015) Health equity in humanitarian emergencies: a role for evidence aid. J Evidence Based Med 8:36–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12137

Rojek MA, Gkolfinopoulou K, Veizis A, Lambrou A, Castle L, Georgakopoulou T, Blanchet K, Panagiotopoulos HPW (2018) Clinical assessment is a neglected component of outbreak preparedness: evidence from refugee camps in Greece. BMC Med 16(43):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1015-9

Roucka T (2011) Access to dental care in two long-term refugee camps in western Tanzania; programme development and assessment. Intl Dental J 61:109–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00023.x

Rutta E, Williams H, Mwansasu A, Mung’ong’o F, Burke H, Gongo R, Veneranda R, Qassim M (2005) Refugee perceptions of the quality of healthcare: findings from a participatory assessment in Ngara, Tanzania. J Disaster 29(4):292–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0361-3666.2005.00293.x

Sami S, Kerber K, Tomczyk B, Amsalu R, Jackson D, Scudder E, Dimiti A, Meyers J, Kenneth K, Kenyi S, Kennedy CE, Ackom K, Mullany LC (2017) “You have to take action”: changing knowledge and attitudes towards newborn care practices during crisis in South Sudan. J Repr Health Matters 25(51):124–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2017.1405677

Sami S, Amsalu R, Dimiti A, Jackson D, Kenyi S, Meyers J, Mullany LC, Scudder E, Tomczyk B, Kerber K (2018) Understanding health systems to improve community and facility level newborn care among displaced populations in South Sudan: a mixed methods case study. BMC Preg Childbirth 18(325):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1953-4

Sondorp E, Kaiser T, Zwi A (2001) Beyond emergency care: challenges to health planning in complex emergencies. Tropical Med Intl Health 6(12):965–970

Stern C, Jordan Z, McArthur A (2014) Developing the review question and inclusion criteria: the first steps in conducting a systematic review. Am J Nursing 114(4):53–56

Tanabe M, Nagujjah Y, Rimal N, Bukania F, Krause S (2015) Intersecting sexual and reproductive health and disability in humanitarian settings: risks, needs, and capacities of refugees with disabilities in Kenya, Nepal and Uganda. J Sex Disability 33:411–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-015-9419-3

Trudeau M, Baron E, Hérard P, Labar A, Lassalle X, Teicher C, Rothstein D (2015) Surgical Care of Pediatric Patients in the humanitarian setting: the Médecins Sans Frontières experience, 2012-2013. J Am Med Ass Surg 150(11):1080–1085. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1928

UNHCR (2018) Figures at a glance. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. http://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html. Accessed 09 December 2018

WHO (2010) Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. World Health Organization, Geneva

WHO (2013) Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014–2023. World Health Organization, Geneva

WHO (2018) Health of refugees and migrants: regional situation analysis, practises, lessons learned and ways forward. WHO African Region, Brazzaville

Zuurmond M, Nyapera V, Mwenda V, Kisia J, Rono H, Palmer J (2016) Childhood disability in Turkana, Kenya: understanding how carers cope in a complex humanitarian setting. Afr J Disability 5(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v5i1.277

Funding

No funds were received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Olabayo Ojeleke (OO) set up the review aim and objectives. OO, Wim Groot (WG) and Milena Pavlova (MP) set up the review protocol. OO undertook the literature search, selection and the final review of the results and findings with the guidance of WG and MP. OO drafted the manuscript. WG and MP provided supervisory assistance to the manuscript drafting and revisions. All authors reviewed the final manuscript and have approved it for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Statement of non-submission of manuscript elsewhere

The authors declare that this manuscript has not been published elsewhere and that it is not under submission for publication elsewhere.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval/review

As this is a review paper, no ethical approval or review is needed for this study.

Consent for publication

The authors of this review have consented to its publication in the Journal of Public Health.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Highlights

• A complex emergency is a humanitarian situation characterized by political instability, violent conflict, large population displacements, social disruption and collapse of public health infrastructure.

• A high level of unmet healthcare need exists among populations affected by complex emergencies (CEs).

• Cultural beliefs and previous health practices of refugees and internally displaced persons have a significant influence on their health-seeking behaviours.

• Culturally sensitive and context-specific care delivery systems are essential in CEs.

• Traditional caregivers could play a complementary role in the delivery of care in CEs.

PROSPERO Reg. No.: 143144

Review protocol available on https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ojeleke, O., Groot, W. & Pavlova, M. Care delivery among refugees and internally displaced persons affected by complex emergencies: a systematic review of the literature. J Public Health (Berl.) 30, 747–762 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01343-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01343-7