Abstract

Purpose

To determine causes of variability in communicable disease prevalence rates among students in secondary schools to inform policy formulation in the public health sector.

Methods

A representative cluster sample size for students was estimated using Fisher et al.’s formula while schools, sub-counties and education zones were clustered and sample size was calculated based on coefficient of variation by school type. Data were collected by questionnaire, medical examination using standard procedures, and focus group discussion, and descriptive analysis was performed on the completed questions. Comparisons between risk factors were made by chi-square and ANOVA analysis using SPSS for Windows (version 15.2; Chicago, IL) software. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

There was significant variation between communicable disease prevalence rates and age (X2 4, 0.05 = 2.458), school size (X2 12, 0.05 = 18.636), gender (X2 4, 0.05 = 5.723) and class of students (X2 12, 0.05 = 15.202), and bed and desk spacing (p < 0.05 at 95% CI). However, there was no significant association in prevalence rates between both locality and type of school. There was strong evidence that student age has an effect on prevalence rates. The prevalence rate of malaria was higher in male (14.02%) than female students (6.68%) compared to prevalence of diarrhea, which was higher in female (7.96%) than male students.

Conclusion

This study has revealed that the prevalences of diarrhea, tuberculosis, pneumonia and other respiratory tract infections are lower among female secondary school students than males and that the prevalence of malaria is higher in males than females. Age of secondary school students is a significant vulnerability factor for malaria, diarrhea, tuberculosis and pneumonia, which were the important communicable diseases most prevalent among secondary school students in Kisumu County, Kenya.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The majority of Kenyans continue to seek treatment in health care facilities for ailments that can be controlled through preventive and promotive measures (WHO 2007), with malaria as the leading cause of morbidity at 30% followed by respiratory diseases (24.5%). Tuberculosis control has been more challenging, with high tuberculosis (TB) prevalence of 319 per 100,000, TB/HIV co-infection prevalence of 53% and a growing threat of multidrug resistance/extra-drug resistance (MDR/XDR) TB (WHO 2008). Overcrowding and intermittent use of antibiotics are some of the challenges facing TB control.

Kisumu County suffers from a high burden of communicable diseases as well as emerging threats. According to the Kenya Demographic and Health Survey by the Government of Kenya (2010), the county has one of the highest HIV/AIDS prevalence rates at 17% higher than the NyanzaFootnote 1 region rate of 15.3% and national rate of 7.4%.

These results have been replicated by a demographic and health survey in Kisumu WestFootnote 2 (KWHDSS 2011), which found high levels of HIV/AIDS, diarrhea, malaria, multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB) and other communicable diseases with more than half of the population relying on surface water as the main source of drinking water while 42% of the households share toilets and 21% have no toilets.

Being a highly disaster-prone county, floods and drought affect different geographical zones annually with a varying degree of damage to the health infrastructure and people’s health, causing interruption of the access to safe water and collapse of the sanitation infrastructure (Mournie 2011). These facts indicate that many people in Kisumu County, students included, are at risk of contracting communicable diseases such as diarrhea, typhoid, intestinal parasite infections, trachoma and schistosomiasis, among others, which account for millions of school days lost (CDC 2007). A major contributing factor to this burden of communicable disease is inadequate access to safe water and sanitation infrastructures (Boschi-Pinto et al. 2008).

The introduction of free schooling in public schools in Kenya has witnessed increased enrollment in secondary schools with the number rising from 1.1 million in 2008 to 1.85 million in 2012 (GoK 2012a, b), leading to increased student membership in the existing hostels and other social amenities in the schools. At present, there is no national guideline to provide a framework for the transformation of school health service into an integrated county health service, while strategies and interventions to work with other ministries have not been spelled out in Kenya’s Health Sector Strategic Plan, 2012–2017 (GoK 2012a, b). Integration of school health services into National and County health services will ensure timely surveillance, prevention and treatment of communicable diseases in schools.

High school students are a neglected group in which very little research has been done concerning the health challenges they face in schools (Muna 2010). There is a need to determine the causes of variability in communicable disease prevalence rates among students to provide baseline information that can be used by policy makers to develop viable intervention programs to address the communicable disease burden in schools.

Materials and methods

The study applied mixed methods to collect and analyze public health-related risk factors using a correlational research design.

Sampling strategy

The first three sub-counties out of the six were purposively selected based on the decreasing value of the coefficient of variation by student gender and type of school. A representative cluster sample size (n = 400) for 60,230 students was estimated using Fisher et al.’s formula, while the sample size per sub-county was based on the coefficient of variation by student gender. Thirty percent of schools, 38 out of 129, were selected based on the coefficient of variation by school type. Students in sampled schools were clustered and selected by cluster sampling. Key informants and observation units were purposively sampled, while focus group discussions were sampled by quota.

Data collection and analysis

A series of data collection tools were used. These included:

-

(1)

Use of a questionnaire to collect data on the locality of the school, type of school, size/enrollment of the school, demographic information and morbidity of students. Bed spacing in hostels and desk spacing in classrooms were observed using an observation checklist.

-

(2)

Focus group discussion guide used to listen and gather information from different people to corroborate data from the field. Thematic issues included groups’ perceptions of skill-based education and a communicable disease surveillance system. An in-depth interview guide was used for index cases.Footnote 3

Students who did not self-report clinically confirmed illnesses in the questionnaire were taken to the nearest health facility for medical examination. The observed medical examination results of interest were:

-

(a)

Blood slides testing positive for the malaria parasite;

-

(b)

A positive culture for Mycrobacterium tuberculosis confirming tuberculosis infection. An acceptable sputum specimen had more than 25 leukocytes and fewer than 10 epithelial cells per lower field. The most common pathogens detected were bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella species. Sensitivity testing was done for positive results;

-

(c)

Positive rapid urine antigen testing for Streptococcus pneumonia;

-

(d)

Positive stool tests for Clostridium difficile for respondents having diarrhea or watery stools. Other tests done were an antigen test for notavirus, ova and parasite examinations and antigen tests specific for the parasites Giardia lambia, Entamoeba, histolyca, Crystosporidium and Parvum.

-

(3)

A descriptive analysis was performed on completed questions. Comparisons between risk factors were made by chi-square and ANOVA analysis using SAS version 9.3. (Carry, NC, USA). A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We ensured the study was conducted within the international standard procedures for medical examinations. As a result medical examinations were carried out in health facilities in the neighborhood of the schools and performed by medical professionals. Verbal consent from participants was obtained before any data were collected. Participants were informed about the intention to utilize data collected for the dissertation and then intervention. Research authorization was sought from the School of Graduate Studies at Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology and the administration of Kisumu County, Kenya.

Results

There were 400 (31%) respondents, 212 male and 188 female students sampled in 38 schools. Characteristics of respondents, including age, gender and classFootnote 4 showed significant variation, p < 0.05; however, there was no significant variation in the religion of respondents. The most predominant student age bracket was 14–17 years, forming 67.8% of the sampled population.

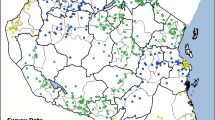

We observed wide geographical variations in prevalence rates of communicable diseases among schools with the highest being malaria at 20.7% and the lowest being pneumonia at 5.2% (Fig. 1).

There was significant variationFootnote 5 in the prevalence of communicable diseases among secondary schools in Kisumu County. This study found a significant association between the communicable disease prevalence rates and age (X2 4, 0.05 = 2.458, Fig. 2) of students, school size (X2 12, 0.05 = 18.636, Fig. 3)/enrollment, gender (X2 4, 0.05 = 5.723, Fig. 4) and class (X2 12, 0.05 = 15.202, Fig. 5)/form of student, bed spacing in hostels (X2 6, 0.05 = 8.21, Fig. 6) and desk spacing in classrooms.

However, for both the locality and type of school there was no significant association with prevalence rates of communicable diseases. Further analysis using ANOVA showed strong evidence that age has an effectFootnote 6 on prevalence rates of communicable diseases among secondary school students.

The prevalence rates of tuberculosis and pneumonia were 7.2 and 5.2% in schools where standard bed spacing in hostels was not observed and 0% for other observations.

A significant association12 between bed spacing and prevalence rates of tuberculosis and pneumonia was observed among students; however, there was no strong evidence that the intervention had an effect.

Prevalence rates of tuberculosis and pneumonia were high at 4.8 and 5.0%, respectively, in schools where standard desk spacing in classrooms was not observed and almost zero percent in schools that observed standard bed spacing. Desk spacing in classrooms and prevalence rates of tuberculosis and pneumonia had a significant association (X2 6, 0.05 = 8.21, Fig. 7) but there was no strong evidence that the intervention had an effect.

Discussion

The prevalence of malaria varies widely from area to area, as has been shown by several studies in Uganda (Nankabirwa et al. 2013; Pullan et al. 2010; Kabatereine et al. 2011). The findings of these studies, which showed that in Uganda 14–64% of school-age children have parasitemia at any one time, concurs with the determined prevalence rate of malaria that we observed (Fig. 1; X2 4, 0.05 = 2.458). This also concurs with the results of a study on the prevalence of malaria parasitema by Gitonga and others (2010) in 480 Kenyan schools between September 2008 and March 2010, which found an overall prevalence rate of 4%; however, this ranged from 0 to 71%. It also agrees with the findings of a study by Dai et al. (2008); Oduro et al. (2013) and others for Senegal, The Gambia, and Mauritania in which the prevalence of malaria infection in school-age children ranged from 5 to 50%.

It is very concerning that malaria prevalence among secondary school students may interfere with their educational development. The effect of malaria infection on school absenteeism has been confirmed in several studies (Leighton and Foster 1993; Brooker et al. 2000) showing that it contributes to between 17 and 54% of school absenteeism per year.

Studies by Lengeler (2004) and Lim et al. (2011) have shown there is strong evidence that, at the individual level, regular use of an insecticide-treated net (ITN) or long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLIN) substantially lowers the risk of malaria infection. This may be attributed to the fact that as children become older and more independent, parents have less control over the time when they go to bed, where they sleep and whether they use a net, frequently resulting in low net coverage in children in this age group. However, evidence is needed to concretize the reasoning.

This study has revealed that student age is a predisposing factor to infectious diseases (Fig. 6). The same results were observed in a study by Baker et al. (2013) on infectious diseases attributable to household crowding in New Zealand, which showed that children less than 5 years old exposed to greater household crowding had 1.69 times the odds of pneumonia as children exposed to the least crowding. The findings of this study showed that the prevalence of tuberculosis and pneumonia is high among students where there is overcrowding in hostels and classrooms (Figs. 2 and 7). It also revealed that students in the 14–17-year age bracket have a higher incidence of tuberculosis and pneumonia than those in the 18 years and greater age bracket16. Findings by the CDC (2007) also confirm these results.

The World Health Organization (WHO 2007), while addressing sex and gender in epidemic-prone infectious diseases, found that differences between males and females arise because gender-based roles, behavior and power.

For most infectious diseases (Fig. 4), the difference in prevalence rates between males and females is more likely to be due to differences in exposure than to differences in immunity. For example, in many societies females spend more time at home than males during the day and therefore experience greater daytime household exposure to infections, for instance caring for the sick and changing baby diapers, than males.

Male students, in their normal lives, spend more time outside the households in the evening than female students, so they are more exposed to mosquito bites than females. This study has revealed that the prevalences of malaria, tuberculosis, pneumonia and other respiratory tract infections are lower among female than male secondary students.

For reasons that are not well understood, a study by WHO (2003) found that females had lower mortality rates from severe acute respiratory syndrome than males, a pattern that was maintained after adjusting for age. Despite the scarcity of information, there are strong indications that sex and gender are necessary for the transmission and control of epidemic-prone diseases.

Age of secondary school students is a significant vulnerability factor for malaria, diarrhea, tuberculosis and pneumonia, which were the important communicable diseases most prevalent among secondary school students in Kisumu County, Kenya.

Notes

Nyanza is an administrative region in Kenya comprised of Kisumu and five other Counties.

Kisumu West is one of the sub-counties in Kisumu County.

Index cases were students with clinically confirmed communicable disease illnesses.

Level of education of respondent

p < 0.05; X2 5, 0.05 = 252.672

p = 0.05 at 95%confidence interval; dF = 3.033

References

Baker MG, Mcdonald A, Zhang J, Howden-Chapman P (2013) Infectious diseases attributable to household crowding in New Zealand: A Systematic review and burden of disease estimate. Available at http://www.healthyhousing.org.nz/publications. Accessed 30 Nov 2014

Boschi-Pinto C, Velebit L, Shibaya K (2008) Estimating child mortality due to diarrhea in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 86:710–717

Brooker S, Guyatt H, Omumbo J (2000) Situation analysis of malaria in school-age children in Kenya—what can be done? Parasitol Today 16:183–186

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2007) Summary health statistics for US children: National Health Interview Survey. Washington DC

Dai I, Konate L, Samb B (2008) Bionomics of malaria vectors and relationship with malaria transmission and epidemiology in three physiographic zones in Senegal River Basin. Acta Trop 105:145–153

Gitonga CW, Karanja PN, Kihara J (2010) Implementing school malaria surveys in Kenya: towards a national Surveillance System. Malar J 9:306

Government of Kenya [GoK] (2012). Education sector. Medium term expenditure 2012/2013–2014/15.January 2012. Government Printer, Nairobi

Government of Kenya [GoK] (2012). Kenya Health Sector Strategic Plan (KHSSP) July 2012–June 2017: Transforming Health; Accelerating attainment of Health Goals

Government of Kenya (GoK) (2010) Population and housing census. Ministry of Planning. Government Printer, Nairobi

Kabatereine NB, Standley CJ, Sousa-Figueiredo JC (2011) Integrated prevalence mapping of schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminthiasis and malaria in lakeside and island communities in Lake Victoria, Uganda. Parasit Vectors 4:232

Kisumu West Health and Demographic Surveillance System [KWHDSS] (2011). Walter Reed Project. Kisumu

Leighton C, Foster R (1993). Economic impacts of Malaria in Kenya and Nigeria, report submitted to the office of Health. USAID, Washington

Lengeler C (2004) Insecticide treated bed nets and curtains for preventing malaria. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews CD000363

Lim SS, Fullman N, Stokes A (2011) Net benefits: a multicounty analysis of observational data examining associations between insecticides treated mosquito nets and health outcomes. PLoS Med 8, e1001091

Mournie M (2011) Health Needs assessment for Kisumu, Kenya. MCI Social Sector Working Paper Series No. 19/2011

Muna BME (2010) Effect of Zinc supplementation on morbidity due to diarrhea in infants and children in Elsabeen Hospital in Sana’a, Yemen. WHO Regional Office for Eastern Mediterranean

Nankabirwa J, Wandera B, Kiwanuka N, Staedke SG, Kanya MR, Brooker SJ (2013) Asymptomatic plasmodium infection and cognition among primary school children in a high malaria transmission setting in Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg 88:1102–1108

Oduro AR, Conway DJ, Schellenberg D (2013) Seroepidemiological and parasitological evaluation of the heterogeneity of malaria infection in the Gambia. Malar J 12:222

Pullan RL, Bukirwa H, Staedke SG (2010) Plasmodium infection and its risk factors in eastern Uganda. Malar J 9:2

World Health Organization [WHO] (2008). Kenya: Epidemiological Country Profile on HIV and AIDS. World Health Organization and UNAIDS. Available at http://app.who.int/globalatlas/predefinedReports/EFS2008/short/EFSCCountryProfiles2008_K.E.pdf. Accessed 01 Jan 2014

World Health Organization [WHO] (2007) Communicable diseases epidemiological profile for HORN OF AFRICA. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization [WHO] (2003) Summary table of SARS by country 1 November 2002–2007 August 2003.At http://www.who.int/entity/csr/sars/country/country2003_08_15.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2004

Acknowledgments

This work was not supported by any organization. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors. All authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors would like to thank the members of the Centre for Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance of Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology for their continued guidance during the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research was fully funded by the corresponding author who is a PhD student at Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology. The research was in pursuit of an academic degree and therefore the other two authors were supervisors.

Ethical approval

Research authorization was granted by the School of Graduate Studies of Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology and the administrators of Kisumu County, Kenya. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. As a result, medical procedures were carried out in health facilities in the neighborhood of the schools and performed by medical professionals.

Informed consent

Verbal consent from participants was obtained prior to the commencement of focus group discussion, in-depth interviews, use of the questionnaire, school transect walking during the environmental health observation and medical examination. Permission to capture some of the research sessions on tape was obtained prior to the event. Participants were informed of the intention to utilize data collected for the dissertation.

Conflict of interest

The authors have not received any grants from any companies. All authors report no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Odongo, D.O., Wakhungu, W.J. & Stanley, O. Causes of variability in prevalence rates of communicable diseases among secondary school Students in Kisumu County, Kenya. J Public Health 25, 161–166 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-016-0777-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-016-0777-9