Abstract

In several Latin American countries, conditional cash transfer programmes are a proven means of alleviating poverty in the short term and promoting education of children from disadvantaged families in the longer run. While the effectiveness of the Brazilian Bolsa Família for children’s education outcomes up to 15 years of age has been widely documented, its contribution to the promotion of students of secondary school age has not been fully explored in light of the programme’s expansion to 16-17 years olds in 2008. In this paper, I draw on Brazilian National Household Sample Survey data and use a difference-in-differences approach already applied in research in the context of Bolsa Família extension. Whereas these data were previously examined to detect intent-to-treat (ITT) effects due to insufficient information on treatment status, in this study I rely on a classifier method to additionally estimate average treatment effects on the treated who belong to families supposedly receiving Bolsa Família cash transfers. The results suggest that school attendance rates for 16-year-olds are particularly increased in the Brazilian Northeast, although the estimates are not significant when further time periods are taken into account. As comparably poor but non-recipient households have larger and consistently significant gains of school attendance, the effect on adolescent’s education directly caused by the expansion of Bolsa Família remains ambiguous and thus cast doubt on the specific parallel trend assumption. In addition, no long-run ITT effects of the programme’s expansion on school participation among 16 year old teenagers are found.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In Brazil, as of 2018, about 40% of the population over 25 years has not yet completed primary school (Globo 2019a). Although the average number of years of schooling has increased from 3.8 years in 1990 to 7.8 years in 2018 according to the Human Development Reports, this figure is still very low by global and even Latin American standards (United Nations Development Programme 2018). A particularly affected age group are young people between 15 and 17 years, since about one in eight stays away from school (Globo 2019b). For this reason, the main focus is on policies that reduce early school leaving and increase the likelihood that more and more young people will obtain higher qualifications. Understanding changes in school absenteeism are fundamental for the educational and long-term economic future of a country, for policy makers and for the effectiveness of social policies.

There is robust evidence for the promotion of educational outcomes through conditional cash transfer (CCT) programmes. In Brazil, the introduction of Bolsa Família in 2003 increased school attendance and completion rates and reduced the number of school dropouts. The average length of schooling has increased by about two years since its introduction. In addition, more than 99% of all children between the ages 6 and 14 now attend school regularly (Globo 2019b). However, due to the fact that school absenteeism is particularly prevalent among children over the age of 15, the support programme began to include 16 to 17-year-olds in 2007/2008. Since the proportion of young people with a secondary school leaving certificate has nevertheless not risen sufficiently, the question arises as to the effectiveness of such programmes.

Previous studies examined the programme effect calculating the intent-to-treat impact.

Replicating the difference-in-differences (DD) regression model used by (Chitolina et al. 2016), I also find positive ITT effects on school participation but conclude that the estimates are sensitive to the use of different time periods and that the influences are heterogeneous in nature. Aiming to achieve more conclusive evidence on the effect on school outcomes, in this paper I try to examine the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) of the expansion of Bolsa Família in 2008 among 16 year olds.

1.1 Educational spillovers effects

In Brazil as a low to middle income country with one of the highest income inequality indices in the world, Footnote 1 educational attainment is important and affects many different dimensions: First and foremost, education impacts on a country’s productivity, the level of income and individual chances on the labour market.Footnote 2 Paes de Barros et al. (2017) estimate that Brazilians with only a secondary school leaving certificate earn about 20% more per month than those with no more than a primary school diploma.Footnote 3

Furthermore, economic theory emphasises the amount of years of education which signals productivity and increases job market opportunities (Spence 1973). In addition, just attending school has an important impact on the students’ social understanding to find their role in the midst of their peer environment. This in turn contributes crucially to the development of social skills, which are elementary for success at work and in life. Another aspect is the attitude towards law and justice since education reduces the likelihood of criminal incarceration (Lochner and Moretti 2004; Machin et al. 2011).Footnote 4 The fact that education is negatively correlated with crime means that investments in this area in particular can hold enormous future potential for Brazil, especially when one considers its overburdened prison system and its low level of public safety compared to other countries. Beyond that, education influences family decisions and vice versa. By 2013, women in Brazil without high school diploma became mothers for the first time between the ages of 19 and 20 on average. Concluding secondary school, on the other hand, increased the age to 22 years (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE 2013).Footnote 5 Also, according to PNAD national household data from 2013, 8% of all girls in Brazil between the ages of 15 and 17 are already mothers. Of those affected, only about one in four attend school, only one in eight of them has a job (Globo 2015).

Increased education relates not only positively to reduced (teen) fertility (Olson et al. 2019), it also effects better health results and reduces mortality.

1.2 Estimating the causal impact of Bolsa Família

The exact estimation of the Bolsa Família cash transfer effect on schooling or labour outcomes is difficult for several reasons. First, self-selection is present in the implementation of the intervention, which, based on unobservable characteristics, contributes to the fundamental difference between treated and non-treated units and would therefore cause OLS regression estimates to be biased. Secondly, given cross sectional household data from Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicilios (PNAD), the occurrence of an actual intervention is not directly observable for the relevant treatment periods. The DD design and a classifier method used for this work try to solve these two points. One part of this approach is to infer the treatment on individuals by applying a set income limit as exclusion criterion of the programme. Instead of using the resulting intent-to-treat (ITT) estimator, in a second step, a classifier matches the queried incomes from social programmes with the benefit levels of Bolsa Família from each respective year to determine actual treatment status. The corresponding DD interaction term consequently represents the estimated average effect on the treated (ATT). Another mechanism is the exploitation of the age rule inherent in Bolsa Famílias extension since the division into treatment and control group is based on two slightly different age groups defining the reception (16-year-olds) or non-reception (15-year-olds) of the programme. As a result, both control and treatment groups are supposed to differ only slightly in terms of individual characteristics due to this income and age restriction. In fact, with regard to key socio-economic variables that could affect educational success, the two groups do not differ significantly from each other in most cases. Also, in order to raise the precision of the regression, a covariates vector emulating the one constructed by Chitolina et al. (2016) is added to the equation. Given the parallel trends assumption, it can be argued that the estimated effect is causal. The PNAD data used cover the years 2001 to 2015 with the exception of 2010.Footnote 6 As Chitolina et al. (2016) I previously had found significantly positive estimates on schooling for the entire country when using the ITT approach for the time span 2006-2009.

However, aiming at yielding ATT estimates for 2006/2009 and 2007/2009 intervals I find no significant treatment effects for 16-year-olds for the whole country in either period after accounting for additional controls, either in rural or urban areas. Though, I detect positive programme influences on school attendance in the Northeast for the first period, particularly pronounced for males. Additional placebo tests for non-treated groups reveal larger positive effects on school participation among ”fake” treatment groups, both in the Northeast and in national samples. Finally, I draw on five extra treatment periods (2011-2015) alongside additional pre-treatment years to examine the (ITT) effect from a longer-term perspective. In this context, I conduct heterogeneous analyses for different geographical regions by gender. There is no significant impact of the programme on additional school attendance rates in the longer term detectable. The overall (direct) effect of the Bolsa Família programme expansion on school participation therefore remains uncertain.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In the next Section 2, I will go into more detail about the relevant literature. After that, in Section 3, I describe the institutional background of the Brazilian education system and of Bolsa Família. In Section 4, I present the data. In Section 5, the empirical strategy applied and based on the paper by Chitolina et al. (2016) is explained. Afterwards, in Section 6, I summarise the results of the estimates. Finally, Section 7 concludes presenting final considerations.

2 Literature review

There is general evidence that conditional cash transfers do have positive and significant impacts on school outcomes (for an overview: Glewwe and Muralidharan (2016) and Filmer and Schady (2011)).

For the case of Brazil, there are considerable evidences on schooling outcomes. De Janvry et al. (2012) use household data and select a quasi-experimental difference in differences approach. For the predecessor of “Programa Bolsa Família” (BFP), Bolsa Escola, the authors estimate a reduced dropout rate of more than 8 percentage points between 1999 and 2003 in the Brazilian Northeast. A DD design is also chosen by Glewwe and Kassouf (2012): They make use of school census panel data from 1998 to 2005 and detect positive ATEs (average treatment effects) among all assigned students (up to 14 years) on attendance, attainment and negative impacts on dropout rates. Ferro et al. (2010) utilise PNAD data from 2003 and apply propensity score matching. They find positive effects on school enrolment (up to 4 percentage points) and negative impacts on child labour especially in rural areas (6-9 percentage points). When analysing the effects of BFP on youth and adult labour, results are mostly insignificant and negligible. Barbosa and Corseuil (2014) exploit the cut-off age exclusion rule for 16-year-olds valid in 2006 and compare marginally separated cohorts by employing a fuzzy RDD. They do not find effects on household labour supply neither in the extensive nor in the intensive margin towards informal work. Ribas and Soares (2011) evidence no statistically significant effects on labour force participation. Also, Ferro and Nicollela (2007) identify insignificant estimates of the work impact in the extensive and intensive margin for both boys and girls.

The expansion of the BFP for 16-17 year olds in 2008 through the introduction of the Beneficio Variável Jovem (Variable Benefit for Youngsters - VBY) allowed the study of educational success and effects on labour outcomes for older adolescents. Reynolds (2015) investigates this extension by conducting a triple difference in differences approach comparing school outcomes between sixteen and seventeen year olds throughout the transition period. She finds increases in school attendance for 16-year-old teenagers with urban boys contributing the most to this significant effect of six percentage points. On the other hand, no respective effects can be stated for the 17-years-olds who were not eligible one year before treatment in 2007. Furthermore, the author evidences only little effects on work outcomes. In a more recent paper, Machado et al. (2018) utilise the programme’s birthday exclusion rule assuming therefore random assignment close to the cut-off date to investigate the VBY impact on 18 year old teens in the Brazilian state of Rio de Janeiro. The authors find positive enrolment effects only for boys amounting to 5.5 percentage points with no implications on school progress. De Brauw et al. (2015) avail themselves on CadÚnico longitudinal household survey data on programme beneficiaries and non-recipients from 2005 and 2009. The authors employ a propensity score weighting strategy and estimate positive ATT impacts on school attainment and enrolment especially for urban girls of 15-17 years. Their findings for boys are mostly insignificant.

Chitolina et al. (2016) are the main reference for this work. They rely on PNAD data, applying a difference-in-differences (DD) approach. The calculated effects of programme expansion on school attendance among 16-year-olds are positive. These are larger for boys, in the rural North East and in the urban South East. There are no impacts on work within the extensive margin. Nevertheless, positive estimates of the programme on simultaneous completion of school and work are observed.

The main contributions of this paper are twofold. First, I apply the DD approach using cross-sectional PNAD household data to different time periods and compute insignificant long-term intent-to-treat estimates. Second, to the best of my knowledge, this paper is the first work that seeks to estimate average treatment effects on the treated on school attendance using PNAD household data in the context of the Bolsa Família programme expansion. In this respect, I employ a classifier approach to determine the treatment status within the utilised PNAD data, first discussed in the literature by Paes de Barros et al. (2007) and more recently by Belchior and Gomes (2019). Also, through the possible specification of non-treated groups, additional drivers of previously calculated positive ITT effects can be identified as non-recipients, especially in the Northeast of Brazil, hence challenging the assumption of parallel trends between control and treatment groups that is central to the DD approach. The increase in school attendance rates for 16-year-olds identified in the North East for the period 2006/2009 thus may lead back to causes beyond the programme expansion.

3 Institutional background

3.1 Education in Brazil

Brazil’s basic education in general is characterised by low school quality (see national IDEBFootnote 7 indicators), modest international test results (PISA)Footnote 8 and delays in schooling (Machado et al. 2018): By 2007, less than half of all 15-17 year-olds were enrolled in the age-appropriate secondary school. In addition to the enormous income inequality already mentioned, there is educational inequality in Brazil: A comparison of the school attendance rates of 16-year-olds by income shows that the poorest income quintile is just under 80 percent, while the richest twenty percent attend school to more than 96 percent. Among 17-year-olds, usually in the last grade of secondary school, this gap increases from 16 to about 28 percentage points in attendanceFootnote 9 (Chitolina et al. 2016). This difference is accompanied by considerable consequences both for the later life of the students and for society as a whole. The failure of 15-17 year olds to reach high school graduation through early school leaving is estimated to result in an annual private cost of nearly R$14 billion by 2016 (Paes de Barros 2016). In addition, the author quantifies the social costs that arise from tax losses, anti-crime and additional health care expenditures, among other factors, at approximately R$35 billion each year (about 0.55% of the GDP in 2016), which exceeded the annual expenditure for BFP at that time by about R$8 billion. In logical consequence, since 2009, with the promulgation of the constitutional amendment (Article 208), the universalisation of schooling between the ages of 4 and 17 has been Brazil’s educational policy goal. Footnote 10 However, the challenges for universalising schooling remain striking, due to socioeconomic inequalities in Brazil. In addition to a generally underfunded public school system , which makes learning success more difficult for children, early school leaving is often based on short-term projections and, of course, economic constraints: According to Neri (2009), of all 15-17 year olds who have already left school, 40% cite lack of interest as their main motive, for 27% work is the main reason. Although, from a legal point of view, work is only allowed from the age of 16, in PNAD 2006 more than 22% of 15-year-olds stated that they had a job (Bursztyn and Coffman 2012). Of course, this trend continues in the later age cohorts 16 (30% worked) and 17 (37% had a job) (Neri 2009). As indicated above, leaving school prematurely leads to long-term disadvantages in the Brazilian labour market. Both employment and remuneration are much lower for people without a secondary school leaving certificate.Footnote 11 Without this degree, there is also no access to the tertiary education sector, which is essential for a substantial improvement in personal economic prospects.

3.2 Bolsa Família

The first two CCT programmes in Brazil were introduced locally in 1995: ”Bolsa Escola” in the federal district of Brasília and PGRFMFootnote 12 in the city of Campinas. Three years later, in 1998, Bolsa Escola was implemented on a national basis. By unifying Bolsa Escola with three different pre-existing benefits for alimentation, childhood care and household energy, the ”world’s largest” CCT (Brollo et al. 2020; Glewwe and Kassouf 2012) Bolsa Família was introduced in late 2003. The programme is managed by the Federal Ministry of Social Development and Fight against Hunger (MDS). At the beginning of BFP, the funds were allocated to the respective communities through a local poverty determination. Based on the national census of 2000 and PNAD 2001, this monetary threshold was estimated at a per capita income of R$100 (at that time about USD 50), almost half of the minimum wage then (Ribas and Soares 2011). This resulted in a target of 11.2 million eligible families, representing approximately 25% of the total population in this period. In the course of the programme, the payments to the lower income quintile were increased proportionately from 40% in 2004 to 60% in 2012 (de Souza et al. 2019). This makes the BFP by far the most targeted programme in the world, according to the authors. Coverage rose from 200,000 families in 2001 to 11.1 million in 2006 (Olson et al. 2019 and Ribas and Soares 2011). Since about 2014, the proportion of Bolsa Familia recipients has been about 14 million families, representing about 20% of the total Brazilian population. In order to receive the aid, families must register locally in the respective community. This data is then compiled nationally in the Cadastro Único (Single Registry) database by the bank ”Caixa”, that is in charge of disbursement. The final approval of the grant is made by means-testing mechanisms and is the responsibility of the federal authority (Lindert et al. 2007).Footnote 13 Entitlement to BFP depends on earnings, which causes general treatment and control groups to differ in socioeconomic aspects. Eligible are people with an household income per capita below a specific poverty line. In 2004, it was defined to be 100 Brazilian Reais, in 2006 it was 120 R$ and in 2009 it rose to 140 R$ (Table 1).

Up to 2007, BFP consisted of two key components: Firstly, an unconditional payment (Basic Benefit) for people below a specific ”extreme” poverty line and secondly, a conditional, Variable Benefit (VB) for children up to secondary school students until 15 years of age from families below another poverty line (”poor”).Footnote 14 The latter requires to this day regular health exams in early childhood, children must also meet the vaccination schedules and - since 2011 - pregnant women are eligible for the subsidy and required to attend prenatal appointments in order to receive the benefits. In addition, pupils must be physically present for at least 85% of the lessons.

The significant drop-out rates for 15-17 year olds, prompted legislators to expand the programme. In December 2007, the Brazilian federal government introduced an additional benefit for adolescent students (VBY). Now 16 and 17 year olds were also supported through a monthly payment of a per capita supplement of R$30 (about USD 15 at the time). By 2008/2009, this amount was 50% higher than the support for children aged 0-15 (R$20).Footnote 15 In contrast to younger students (85%), attendance became compulsory for at least 75% of the lessons.

4 Data

Data sources are from the National Household Sample Survey (PNAD), which was conducted annually until 2015 by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). I use PNADs remaining data between 2001 to 2015 (with the exception of 2010, when no study was conducted). The datasets are cross-sectional surveys and typically consist of about 150,000 families and about 390,000 individuals each year (Reynolds 2015), querying socioeconomic and household characteristics. A major drawback of PNAD data is the general lack of clear information from families about participation in the Bolsa Família programme. Nevertheless, for the pre-treatment years 2004 and 2006, supplementary data exist that clarify the question of receiving Bolsa Escola and Bolsa Família. It can be concluded that about half of all PNAD recipients in 2004 belonged to the first two income deciles, which is plausible because of their adherence to the programme’s income limit (Chitolina et al. 2016). For the year 2006, I observe similar results in the data.

I hence follow the approach by Chitolina et al. (2016) in selecting the first income quintile, located within the income limit as the main criterion for participation in the programme.

4.1 Treatment classifier

In addition, I refer to the strategy used by Paes de Barros et al. (2007) to determine treatment status. The amount of income received from social programmes is summarised, among other income, in the PNAD variable ”v1273 - Value of income received from interest, dividends and other”. In their paper, Paes de Barros et al. (2007) examine the variable and compare it with the legal level of social welfare originating from Bolsa Família/Bolsa Escola, Footnote 16 BPC (Benefício de Prestação Continuada ), Footnote 17 and PETI (Programa de Erradicação do Trabalho Infantil),Footnote 18 in order to derive the actual coverage of the individual social programmes separately. The indicator they develop identifies 95 percent of all Bolsa Família recipient households actually stated in PNAD 2004. Moreover, of the estimated total number of recipients, over 86% are actual beneficiaries of BFP, which means that about 13-14% are not recipients of the programme.

After first filtering the dataset for families from the first two income deciles (family income per capita) as described above, I repeat this procedure for 2006.Footnote 19 Trying to minimise the error rate, I exclude as many false-positive results as possible. On the one hand, this leads to a smaller sample and thus to higher standard errors in principle. On the other hand, the estimator of the causal programme effect is - given a sufficiently large sample - closer to the true (ATT) parameter if nearly all individuals in the estimated treatment group actually receive an intervention.

Contingency Table 2 presents the results of the classifier developed to predict beneficiary status in 2006. The method used, allows to define slightly less than 81 percent of all actual recipients belonging to the first income quintile (true positive rate). Furthermore, more than 96% of all estimated beneficiaries actually receive social assistance through Bolsa Família. This rate represents the positive predictive value and measures the precision of the classifier. Conversely, this again means an erroneous inclusion of false recipients, a false discovery rate, of 3.7 percent. The graph Fig. 1 compares the monthly grant distribution (in natural logs) of the true Bolsa Família recipient households according to PNAD with that of the recipients determined by the classifier. It is striking that despite small deviations in the frequencies (median income of the classifier sample), the shape of the two distributions is similar.Footnote 20 I then apply this procedure to the years 2007 and 2009 and compare the entries of the PNAD variable (v1273) with the respective official payment levels and possible combinations, which vary depending on the number of children under 15 and 16-17 year olds in the households. Of the possible Bolsa Família amounts listed in Table 3, I take into account the ones in bold, incorporating the above-mentioned household sizes. To increase precision, I also consider the grant distribution of recipient households observed in 2006 as well as the general distribution of payment levels for the subsamples in 2007 and 2009.

4.2 Summary statistics

The following summary statistics Table 4Footnote 21 compares the treatment and control group samples from 2006 obtained by the income restriction and the classifier method carried out thereafter. 15-year-olds form the control group, while 16-year-olds represent the treatment group. The sample obtained for the pre-treatment year 2006 is 1,336 observations, of which 577 teenagers belong to the treatment group and 759 adolescents to the control group.

It is striking that the treatment group is on average larger than the control group in terms of household size and (related) number of children in the household and differs significantly from the control group. In addition, it is noticeable that the average age of the youngest child in the treatment group is significantly lower than that of the control group. Furthermore, the age of the oldest child in the household as well as the remuneration through work for children and their total number of weekly working hours is significantly higher than the corresponding values in the control group. While the size of the household could influence the educational success of the children to a certain extent, since resources could be distributed in a more concentrated manner in smaller families, the above-mentioned differences in the age and work characteristics of the children are primarily due to the general age difference between 15 and 16 years of age (the latter even more so when the official age of entry into employment of 16 years is taken into account). With regard to all other characteristics, both groups are not distinguishable from zero in their averages: The age, education, pay and workload of the parents, the age of the head of household, as well as geographical and ethnic characteristics and the data on the Bolsa Família recipient status (both 96%) are numerically comparable in control and treatment groups and do not differ significantly in their respective means.

5 Estimation strategy

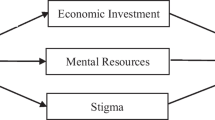

The hypothesis behind this paper is that an increase in benefits to adolescents of 16 years raises school participation outcomes. This is why I estimate the impact of VBY on school attendance through a lineary probability model for binary dependent variables. I follow (Chitolina et al. 2016) and use a DD-regression design with the following specification:

with Treatit being a dummy variable for treatment and Aftert as another indicator for the period after intervention, in this case 2009. The dependent variable Yit measures actual school attendance and is an indicator. Xit is a vector of covariates. I reconstruct it using the PNAD variables considered by Chitolina et al. (2016) and control for: number of children in households, educationFootnote 22, age of head, household compositionFootnote 23, eight different urban and rural areas for the whole sample and state dummies. The inclusion of these covariates reduces the error variance and improves identification by increasing the precision of the causal effect estimator which is captured by the interaction term for VBY beneficiaries during post-treatment Treati ∗ Aftert. Lastly, the error term, 𝜖it, accounts for all unobserved characteristics left that affect the response variable. This causal effect relies on the following assumption:

where, Di denoting treatment status, the unobserved error differences in both periods are equal between control and intervention group.

The internal validity of this research design is crucial to measure reliable causal programme effects, considering the non-experimental implementation of Bolsa Família.

In BFP, selection bias is present since entitlement depends on (self-reported) income levels and requires the recipient family to become active through its own registration. These different family attributes in turn might correlate with the outcome variables and would consequently lead to confounding bias. Let us assume that due to different incomes of their parents, the students also differ in education of their parents, upbringing, equipment and other factors that correlate with the educational success of the children. In this case, treatment and control units differ with regards to unobservable and observable characteristics that influence the dependent variable ”school attendance”, i.e.:

where this term captures the differences in average school attendance outcomes between the treatment group had they not been treated (through VBY) and the control unit (Angrist and Pischke 2008). The DD estimation strategy accounts for selection bias due to the parallel-trends assumption stated in Eq. 2. In addition, the programme-specific expansion for 16-17 year-olds can strengthen the credibility of parallel trends and thus underpin the identification of the causal effect as follows: Selecting only 15 and 16 year-olds of the 20% poorest families leads to greater comparability of the groups, as both units would be eligible for the treatment with respect to income. Also, a division into control (15-year-olds) and treatment units (16-year-olds) is only made on the basis of the slightly different age.

A further advantage of a DD design is the possibility to include regressors into the specification that come from rich individual-level data: By taking into account the covariates vector discussed in chapter 4, the estimated effects are closer to the true value.

However, we cannot rule out the possibility that we may overlook time-variant unobservables that occur between the pre-treatment and post-treatment periods and affect each group’s dependent variable differently. Of importance for this assumption is the significant disparity in school attendance rates between 15 and 16 year olds. One of the reasons for the differences in levels is certainly the start of secondary school in Brazil in the 14-16 age range, where within the first two income deciles, 16-year-olds are significantly more likely to attend secondary school than 15-year-olds. In the absence of the programme, 16-year-olds could thus exhibit different trends of school participation than their 15-year-old counterparts for the period up to 2009. Yet, anticipation effects among the control group and as a barrier to the chosen strategy do not seem to apply to any of the pre-treatment years 2006 and 2007 in the author’s understanding, due to lack of prior knowledge of the Bolsa Família expansion and rather short-term schooling decisions despite proven long-term benefits of higher education for career success in Brazil (on this, see also Belchior, 2019).

5.1 Pre-trend-analysis

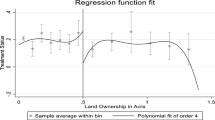

To further check the comparability of the samples obtained by the indicator described above, I additionally determine treatment and control groups for the years 2004 and 2005 and graphically analyse the possible existence of pre-trends of the outcome variable for the period from 2004 to 2007 before the introduction of the treatment.

In Fig. 2, an almost constant discrepancy in school attendance rates between the two cohorts can be found in the overall length of the observed period. Thus, the 15-year-olds start at a frequency of about 81.2%, whereas the 16-year-olds in 2004 start at a participation rate of 74.0%. A positive, parallel trend until 2006 follows. This year the signs are reversed, while the control group continues to increase school attendance, it decreases in 2006 for the treatment group. The concluding year 2007 is in contrast characterised by a rise for the 16-year-olds, reaching a rate of about 78.0% (compared to 85.5% within the control group of 15-year-olds). Over the whole period up to the time the policy was introduced (2008), the difference in the dependent variables increased by 0.3 percentage points. Although the experimental and control groups show similar pre-trends, it cannot be ruled out that the school attendance rate of the control group would develop differently from that of the intervention group in the absence of the treatment. Due to the drop in school attendance rates of the treatment group for 2006, one could expect an upward biased estimate of the treatment effect for the period 2006/2009.

6 Results

To estimate the programme’s ATT on school attendance I use Eq. 1.Footnote 24 In the following results, I conduct regression analyses for the periods 2006/2009 and 2007/2009 to detect the school effect of expanding Bolsa Família. I find significant effects solely for the former period for the Northeast, especially for boys: Table 5 presents the different regressions for the entire region as well as for urban and rural Northeast. The total effect (column 2) taking into account the controlling variables is 7.4 percentage points (significant at a 5 per cent level). In the urban Northeast (column 3), the impact of the programme on school attendance rates is positive, though insignificant. For the rural Northeast (column 4), the result amounts to 8.1 percentage points, significant at a 10 per cent level. Further, Table 6 illustrates the estimated effect of the programme expansion on boys living in the Northeast: Column 1 maps the overall impact and shows that the growth in school presence in the North East is mainly explained by the increase for boys. The estimate is 11.3 percentage points and it is significant at a 5 per cent level. Columns 2 and 3 present the subdivisions: for boys in the urban North East (column 2) the effect turns out to be positive but insignificant, for boys from rural areas of this macro-region (column 3) the estimate is 13.0 percentage points (significant at a 10 per cent level).

In contrast to these results, programme effects examined in a separate analysis for the North East prove not to be significant for the period 2007/2009. The same applies to possible effects all over Brazil, whether urban or rural, for both 2006/2009 and 2007/2009. In the following regression Table 7, we see that all specifications - with or without covariates vector, in rural or urban areas - show no significant average treatment effects on the treated when referring to school participation. Column 1 contains no other controls and shows a positive, statistically indistinguishable from zero, interaction term of 4.1 percentage points. Column 2 includes additional controls from the previously applied regressions, which breaks down the effect from column 1 to 1.1 percentage points and is also insignificant. For urban areas in column 3 the DD estimator is slightly negative at 0.6 percentage points, for rural areas in column 4 it is positive at 3.3 percentage points, but in both cases, as described above, the estimates are not significant.

The effects identified are of a heterogeneous character and are found in the Northeast for the period 2006/2009 among boys. For all other estimates, no significant impacts of the expansion of Bolsa Família on school attendance can be detected if, beyond the narrowing of the sample by the first two income decimals, only allegedly treated families are considered.

6.1 Placebo tests

In this section, I check the results found with the help of the classifier method described above. For this placebo test, I only consider individuals from households with “NA” entries in the variable “v1273”, since Bolsa Família amounts from all recipients declared in the PNAD are broken down under this variable and entries must consequently be larger than zero.Footnote 25 Here again, the control group consists of 15-year-olds, while the 16-year-olds form the treatment group. As the previous sample, both groups belong to the first income quintile and therefore have similar socio-economic conditions. Since this is a fake treatment, it would be expected that the evolution of the school attendance rates of 15- and 16-year-olds would be similar if the parallel trend assumption were to hold.

In the following Table 8, I examine the impact of programme expansion on school participation in the North East for the years 2006 and 2009. Whereas the related ATT estimates for this period were positive and significant, it is striking here that they are larger in magnitude, both for the North East as a whole in column 1 (12.0 percentage points) and for 16-year-old boys living there (18.2 in the whole North East and in urban areas 19.4 percentage points). Assuming a school attendance rate for the treatment group comparable to the ATT sample for 2006 (about 73%), the increase in the urban northeast may represent a relative growth of more than a quarter. Almost as large is the gain in school participation rates of this placebo-treatment group for the period 2007/2009.Footnote 26 Further, the estimates for period 2007/2009 are significant and positive for the whole country. Table 9 shows the individual effects for the whole of Brazil including controls (column 2), subdivided into urban (column 3) and rural areas (column 4). Also, the estimates for the period 2007/2009 are significant and positive for urban Brazil (see also Table 9).

6.2 Multiple time period design

This ITT analysis involves an extension of the Differences in Differences approach incorporating multiple time periods for the available data from 2001 to 2015. In Figure 3 we see the development of school attendance rates of 15- and 16-year-olds up to the year 2015. Although it is apparent that by the year 2009, a relative convergence of the school attendance rate between 15 and 16 year-olds can be observed, nevertheless, the gap between the control and experimental groups widens again in the following years until 2015.

School attendance rates for 15 and 16 year olds from the first income quintile across Brazil between 2001 and 2015 (except for 2010 data, as no PNAD was conducted for that year). The vertical line marks the start of the treatment. Grey shaded areas indicate the respective 95% confidence interval of the cohorts

For the subsequent regression, I consider the specification (1) used in Section 5 with the time interval 2001-2007 as the pre-treatment period, while the years 2008-2015 fall under the dummy variable “Aftert”, indicating one. As before the interaction term includes the causal effect of the expansion of Bolsa Família on the school attendance rate of 16-year-olds. By considering more than two periods than in the canonical model, the intention is to make the estimate more precise and reliable (Angrist and Pischke 2014).

In sum, the effect decreases when considering further time periods until 2015 and the interaction term is not significantly different from zero when using the covariates vector in the pertinent specification. This applies to urban as well as rural Brazil.

7 Final considerations

In the background of the expansion of Bolsa Família in 2008, previous ITT estimations on school participation among 16 year old adolescents exhibit positive and significant results (especially for boys), as stated in the work of Chitolina et al. (2016) and Reynolds (2015). Identifying actual treatment by means of classifier, in this paper, I try to compare these findings on school attendance with estimated average treatment effects of the treated. The ATTs found in this work suggest solely regionally significant results in the Northeast of Brazil - for one of the two periods tested (2006/2009). There are no statistically significant effects on school participation caused by the progamme expansion of Bolsa Família either for the country as a whole or for other geographical areas in both periods 2006/2009 and 2007/2009. Having incorporated a placebo test, the final conclusion regarding the contribution of the Bolsa Família expansion to raising school attendance remains difficult, as even untreated 16-year-olds increase significantly more in school presence compared to 15-year-olds, and even to a greater extent than the ATT estimates. This in turn suggests that the Parallel Trends assumption between the selected control and treatment groups for the respective time period might not be valid.

In a previously conducted ITT analysis, I also found that the estimated cross-regional effects on schooling decrease and become mostly insignificant when changing the base year from 2006 to 2007. In addition, there is a clear decline to be observed especially in the strongly influenced Northeast. Secondly, no long-run effects are found being statistically different from zero. Overall, the existence of placebo effects and the prevalence of sensitive outcomes raise the question of the extent to which reliable calculations are possible using PNAD cross-sectional household data aiming to estimate (ITT) effects. For example, the strategy of the lowest income quintile may fit the national eligibility criteria in terms of size. However, conditions, individual’s characteristics and number of beneficiaries may vary regionally and in time, thus distorting heterogeneous estimates. In this context, additionally resorting to a classifier method that enhances the quality of the information regarding the family’s treatment status may be useful to check the model’s validity. It should be kept in mind that due to the consequent underestimation of recipients number in PNAD data mentioned in the literature, declared non-recipients of Bolsa Família might still be treated. Positively estimated placebo effects for 16-year-olds could also be partly due to this circumstance, in addition to spillover effects. Another disadvantage of the PNAD data is the partial limitation of the outcome variable, which only provides information on the current school attendance at the time of the survey.

For further studies of the school effects of the expansion of Bolsa Família, the coupling of different databases in particular can be useful. The merging of panel datasets, such as the programme payroll database, the registered entries in the Cadastro Único or school databases such as Censo Escolar, are of particular importance, as they provide more detailed information on the same (de-anonymised) individuals, their characteristics including recipient status as well as school performance and attendance. Furthermore, with this approach it is possible to identify local effects at municipal basis. Having additional individual-level employer-employee datasets (RAIS) available, an examination of the VBY impact on the youth’s future job market outcomes should be taken into account.

In sum, it is questionable to which degree the programme expansion achieves its goal of increasing the school participation of over 15 years old teenagers, ideally raising the completion rate to ultimately reduce the educational gap between low- and high-income groups. This is seen to be crucial to alleviate the intergenerational inequalities existing in Brazilian society. In addition to the necessary investments in the public school system, support targeted at early childhood could be particularly promising in this context to increase academic success in adolescence and beyond.

Notes

In a country comparison using the latest GINI coefficients, Brazil is the most unequal country outside Africa (World Bank 2018).

Reynolds (2015) also stress the important role of the conclusion of the ensino médio and estimate for 2006 a similarly high income effect of 23% even for younger cohorts.

In Brazil, the country examined in this article, as of 2018, 90% of all detainees have not obtained a secondary school leaving certificate (ensino médio) before their sentencing (Ministério da Nacional Justiça e Segurança Pública do Brasil 2018).

These years can be decisive for a woman’s future (financial) independence due to lack of educational or work experience.

No PNAD was produced in that year due to the implementation of the census.

Índice de Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica - Basic Education Development Index.

Programme for International Student Assessment.

66% for students from poorer families versus 94% for students from richer backgrounds.

The adoption of the Education Plan (PNE) regulates the specific goals, according to which all Brazilians between the ages of 15 and 17 must be enrolled. In addition, there is still a requirement that 85% of these students in this age group attend at least secondary school by 2024.

According to Neri, in 2007 the average salary of secondary school graduates (regardless of socioeconomic characteristics) was about 40% higher than that of those with only a primary school diploma (Neri 2009).

(Programa de Garantia de Renda Familiar Mínima.)

The main selection criteria are per capita income below the poverty threshold and family size, which the larger it is, improves the family’s position in an eligibility ranking.

(This line is twice as large the extreme poverty line.)

Over the following years, the premium for 16-17 year olds decreased. In 2020, the subsidies were R$41 and R$48 respectively.

(including subsidies for gas and food)

A social benefit for people over 65 and/or with disabilities equivalent to the current minimum wage

A programme designed to eliminate child labour and, from 2005, officially part of Bolsa Família

After examining the actual recipient households, the validity of the applied method by the authors is also given in 2006, as the entries in the PNAD variable are always greater than zero.

Also, the difference between the two arithmetic means (R$ 93,261 and R$ 92,982 per month) does not differ significantly from zero.

Table created using the R package by Hlavac (2018).

Here, I use the maximum amount of schooling represented by one of the two spouses.

In total, PNAD data considered eight different family types.

This ATT estimator measures the effect of the additional amount of money provided by the extension. Families that, according to the classifier, were not Bolsa Família recipients before the introduction of VBY are excluded in the DD approach. Consequently, new recipient households from 2008 onwards would be expected to show a comparatively higher increase in school attendance rates for youth aged 16-17 due to the support of the whole family by the Basic Benefit or the Variable Benefit for additional siblings. This is because their counterparts from existing recipient households would have been at least indirectly exposed to treatment beforehand. Furthermore, the classifier approximates the treatment status of the entire family and does not provide a definitive inference about the support of the presumptively treated youth. Thus, in turn, non-receipt of this treatment would only result from the inactivity at school and not from the family’s ineligibility.

In a check for the period 2006, there is not a single social assistance recipient among these ”NA” entries.

The positive results for the Northeast are repeated for the period 2007/2009.

References

Aghion P, Howitt PW (2008) The economics of growth. MIT press, Cambridge

Angrist J D, Pischke JS (2008) Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Angrist J D, Pischke JS (2014) Mastering’metrics: The path from cause to effect. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Barbosa A, Corseuil C (2014) Conditional cash transfer and informality in brazil. IZA Journal of Labor & Development 3:1–18

Paes de Barros R (2016) Abandono escolar de jovem tem custo igual a gasto do país com ensino médio. https://www.insper.edu.br/noticias/abandono-escolar-de-jovem-tem-custo-igual-a-gasto-do-pais-com-ensino-medio/ Online; Accessed 22 May 2021

Paes de Barros R, de Carvalho M, Franco S (2007) O papel das transferências públicas na queda recente da desigualdade de renda brasileira. Desigualdade de renda no Brasil: uma aná,lise da queda recente 2:41–86

Paes de Barros R, et al. (2017) Políticas públicas para redução do abandono e evasão escolar de jovens. Fundação Brava Instituto Unibanco, Insper, Instituto Ayrton Senna

Belchior C A, Gomes Y (2019) Her money, their chores: Bargaining over domestic work in brazil, paper presented at the annual lacea - lames meeting, 2019 https://sistemas.colmex.mx/Reportes/LACEALAMES/LACEA-LAMES2019_paper_552.pdf. Online Accessed 22, May 2021

Brollo F, Maria Kaufmann K, La Ferrara E (2020) Learning spillovers in conditional welfare programmes: evidence from Brazil. The Economic Journal 130(628):853–879. https://academic.oup.com/ej/article-pdf/130/628/853/33377465/ueaa032_online_appendix.pdf

Bursztyn L, Coffman L C (2012) The schooling decision: Family preferences, intergenerational conflict, and moral hazard in the brazilian favelas. J. Polit. Econ. 120(3):359–397

Card D (1999) The causal effect of education on earnings. In: Handbook of labor economics, vol 3. Elsevier, pp 1801–1863

Chitolina L, Foguel M N, Menezes-Filho N A (2016) The impact of the expansion of the bolsa família program on the time allocation of youths and their parents. Rev. Bras. Econ. 70(2):183–202

De Brauw A, Gilligan D O, Hoddinott J, Roy S (2015) Bolsa família and household labor supply. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 63(3):423–457

De Janvry A, Finan F, Sadoulet E (2012) Local electoral incentives and decentralized program performance. Rev Econ Stat 94(3):672–685

Ferro A, Nicollela A (2007) The impact of conditional cash transfers programs on household working decision in Brazil. São Paulo

Ferro A R, Kassouf A L, Levison D (2010) The impact of conditional cash transfer programs on household work decisions in Brazil. In: Child labor and the transition between school and work. Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Filmer D, Schady N (2011) Does more cash in conditional cash transfer programs always lead to larger impacts on school attendance? J. Dev. Econ. 96(1):150–157

Glewwe P, Kassouf A L (2012) The impact of the bolsa escola/familia conditional cash transfer program on enrollment, dropout rates and grade promotion in brazil. Journal of Development Economics 97(2):505–517

Glewwe P, Muralidharan K (2016) Improving education outcomes in developing countries: Evidence, knowledge gaps, and policy implications. In: Handbook of the economics of education, vol 5. Elsevier, pp 653–743

Hlavac M (2018) Stargazer: Well-formatted regression and summary statisticstables. r package version 5.2.2 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=stargazer. Online Accessed 22, May 2021

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE (2013) Pesquisa nacional de saúde : 2013 : ciclos de vida : Brasil e grandes regiões / ibge, coordenação de trabalho e rendimento. https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv94522.pdf. Online Accessed 22 May 2021

Krueger A B, Lindahl M (2001) Education for growth: Why and for whom? J Econ Lit 39(4):1101–1136

Lindert K, Linder A, Hobbs J, De la Brière B (2007) The nuts and bolts of Brazil’S Bolsa família program: implementing conditional cash transfers in a decentralized context. World Bank social protection discussion paper 709

Lochner L, Moretti E (2004) The effect of education on crime: Evidence from prison inmates, arrests, and self-reports. Am Econ Rev 94(1):155–189

Machado C, Pinho Neto VRd, Szerman C (2018) Youth responses to cash transfers: Evidence from Brazil. In: Economic and behavioral effects of safety net programs by V.R. Pinho Neto. PhD thesis

Machin S, Marie O, Vujić S (2011) The crime reducing effect of education. Econ J 121(552):463–484

Ministério da Nacional Justiça e Segurança Pública do Brasil Departamento Penitenciário (2018) Levantamento nacional e informações penitenciárias infopen junho de 2016

Neri MC (2009) Motivos da evasão escolar. www3.fgv.br/ibrecps/TPE/TPE_MotivacoesEscolares_fim.pdf. Online: Accessed 22 May 2021

Globo O (2015) No Brasil, 75% das adolescentes que têm filhos estão fora da escola. http://g1.globo.com/educacao/noticia/2015/03/no-brasil-75-das-adolescentes-que-tem-filhos-estao-fora-da-escola.html. Online: Accessed 22 May 2021

Globo O (2019a) No brasil, 40% da população acima de 25 anos não têm nem ensino fundamental. https://oglobo.globo.com/sociedade/educacao/no-brasil-40-da-populacao-acima-de-25-anos-nao-tem-nem-ensino-fundamental-23745880. Online Accessed 22 May 2021

Globo O (2019b) O desafio de manter jovens no ensino médio, principal obstáculo à universalização da educação. https://g1.globo.com/educacao/noticia/2019/06/20/o-desafio-de-manter-jovens-no-ensino-medio-principal-obstaculo-a-universalizacao-da-educacao.ghtml. Online: accessed 22 May 2021

Olson Z, Clark R G, Reynolds S A (2019) Can a conditional cash transfer reduce teen fertility? the case of Brazil’S Bolsa familia. J Health Econ 63:128–144

Reynolds S A (2015) Brazil’s bolsa familia: Does it work for adolescents and do they work less for it? Econ Educ Rev 46:23–38

Ribas R P, Soares F V (2011) Is the effect of conditional transfers on labor supply negligible everywhere. Unpublished manuscript Tinker Fellowship. Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

de Souza P H, Osorio R G, Paiva L H, Soares S (2019) Os efeitos do programa bolsa família sobre a pobreza e a desigualdade: Um balanço dos primeiros quinze anos. Tech. rep. Texto para Discussão

Spence M (1973) Job market signaling. Q J Econ 87(3):355–374

United Nations Development Programme (2018) Human development reports. http://hdr.undp.org/en/ data#. Online: accessed 22 May 2021

World Bank Development Research Group (2018) Gini index (world bank estimate) https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?most_recent_value_desc=true. Online; Accessed 22, May 2021

Acknowledgements

The topic of this thesis has been on my mind since I studied at PUC Rio, Brazil. I am very grateful for the courses I was able to take at PUC due to the exchange programme, especially I would like to thank Brit Sperber-Fels, Linda Cristina and Prof. Nazareth Maciel as well as Prof. Claudio Ferraz and Prof. Gabriel Ulyssea.

I also want to thank my supervisor Prof. Pia Pinger from my home university for making it possible to conduct the research as part of my Master’s thesis.

In these sometimes turbulent times, I could also always count on the support of close fellow human beings, without whom I would not have been able to write this paper. My special thanks therefore go to Tilmann and to my family Jana, Armin and Grandma. Last but not least, I like to thank Amanda, who always stood by my side - even in moments when others would have given me the boot long ago.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Draeger, E. Do conditional cash transfers increase schooling among adolescents?. Int Econ Econ Policy 18, 743–766 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-021-00505-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-021-00505-6