Abstract

This paper discuss expectation (or news) shocks to government expenditures: consumption or investment spending in an otherwise standard RBC model of the U.S. economy. In addition, we study the differences emerging from modelling fiscal policy with and without fiscal rules. We find that news about future fiscal policy generate dramatically different effects, if fiscal policy follows a rule. Our findings have several implications for the design and the implementation of fiscal policy as well as the estimation of fiscal shocks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The literature uses two terms: first, the term “news” shock is used. A news shock is usually understood to be new information about future technology (or, in general, fundamental) changes. In contrast, an expectation shock does not represent information about fundamentals, instead it captures changes in market sentiment.

The boom-bust cycle of 1999-2001 is often used as an example of this type of expectation driven business cycles. The expectations of higher productivity were one driving force of the high growth rates of the years 1999 and 2000. Then, in 2001, those high expectations have been revised leading to a recession.

In addition, there is a transversality condition that prevents agents from going infinitely into debt.

Leeper et al. (2013) stress that fiscal foresight causes a fundamental problem, as it generates an equilibrium time series that contains a moving average component that is non-invertible in past and current observables.

Note that the government, although it may or may not have private information, is not able to use those information in setting the path of fiscal variables. Perfectly rational agents would observe the deviation between the theoretical path and the actual path and extract information about the accuracy of the signal.

Note that we use the same calibration of fiscal rule parameters as in Leeper et al. (2010).

References

Bassetto M (2005) Equilibrium and government commitment. J Econ Theory 124(1):79–105

Baxter M, King RG (1993) Fiscal policy in general equilibrium. Am Econ Rev 83(3):315–334

Beaudry P, Portier F (2004) An exploration into pigou’s theory of cycles. J Monet Econ 51(6):1183–1216

Blanchard OJ, Perotti R (2002) An empirical characterization of the dynamic effects of changes in government spending and taxes on output. Q J Econ 117 (4):1329–1368

Born B, Peter A, Pfeifer J (2013) Fiscal news and macroeconomic volatility. J Econ Dyn Control 37(12):2582–2601

Christiano LJ, Eichenbaum M, Evans CL (2005) Nominal rigidities and the dynamic effects of a shock to monetary policy. J Polit Econ 113(1):1–45

Forni L, Monteforte L, Sessa L (2009) The general equilibrium effects of fiscal policy: estimates for the euro area. J Public Econ 93(3-4):559–585

Fujiwara I, Kang H (2006) Expectation shock simulation with dynare. QM&RBC Codes, Quantitative Macroeconomics & Real Business Cycles

Hoon HT, Phelps ES (2008) Future fiscal and budgetary shocks. J Econ Theory 143(1):499–518

House CL, Shapiro MD (2006) Phased-in tax cuts and economic activity. Am Econ Rev 96(5):1835–1849

Leeper EM (1991) Equilibria under ‘active’ and ‘passive’ monetary and fiscal policies. J Monet Econ 27(1):129–147

Leeper EM, Plante M, Traum N (2010) Dynamics of fiscal financing in the United States. J Econ 156(2):304–321

Leeper EM, Walker TB, Yang S-CS (2013) Fiscal foresight and information flows. Econometrica 81(3):1115–1145

Mehra R, Prescott EC (1980) Recursive competitive equilibrium: the case of homogeneous households. Econometrica 48(6):1365–1379

Mertens K, Ravn MO (2008) The aggregate effects of anticipated and unanticipated U.S. tax policy shocks: theory and empirical evidence. CEPR discussion papers 6673, C.E.P.R. discussion papers

Mertens K, Ravn MO (2009) Empirical evidence on the aggregate effects of anticipated and unanticipated U.S. tax policy shocks. CEPR discussion papers 7370, C.E.P.R. discussion papers

Mertens K, Ravn MO (2010) Measuring the impact of fiscal policy in the face of anticipation: a structural VAR approach. Econ J 120:544

Milani F (2011) Expectation shocks and learning as drivers of the business cycle. Econ J 121(552):379–401

Mountford A, Uhlig H (2009) What are the effects of fiscal policy shocks? J Appl Econom 24(6):960–992

Ricco G (2015) A new identification of fiscal shocks based on the information flow. Working Paper series 1813, European Central Bank

Ricco G, Callegari G, Cimadomo J (2016) Signals from the government: policy uncertainty and the transmission of fiscal shocks. J Monet Econ 82:107–118

Romer CD, Romer DH (2010) The macroeconomic effects of tax changes: estimates based on a new measure of fiscal shocks. Am Econ Rev 100(3):763–801

Wesselbaum D (2015) Sectoral labor market effects of fiscal spending. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 34:19–35

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I am highly indebted to Gadi Barlevy, Marco Bassetto, Jeff Campbell, Alejandro Justiniano, and Marc Luik for highly valuable comments on an earlier version. Any remaining errors are my own. Furthermore, Iam deeply thankful to the Research Department of the Chicago FED for the opportunity to conduct aresearch visit, the hospitality throughout my stay, and the countless beneficial conversations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 A.1 Solution algorithm

Here, we follow the exposition in Fujiwara and Kang (2006). The solution to a rational expectation model

where Z gives the vector of endogenous variables and S is the vector of exogenous disturbances is given by

Combining those equations gives

The expectation shock is introduced by modifying the B matrix. Suppose a shock process is given by

where ξφ,t−p is the expectation shock that might occur in period p > 0. This shock can be introduced to the shock vector

and by adjusting the following matrices

Then, the new B∗ can be computed and the system can be solved.

1.2 A.2 Technology shock with fiscal rule

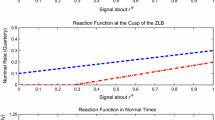

In this section, agents receive a signal about a positive, one percent favorable technology shock and fiscal policy follows fiscal rules with endogenous feedback to macroeconomic variables. Figure 6 presents the impulse responses.

The response of the model economy with fiscal rules is very different to the exogenous fiscal policy scenario discussed before. In contrast, the announcement of an increase in technology decreases output on impact. The reason is the countercyclicality of fiscal variables. We have established that in the absence of fiscal rules output would increase. With fiscal rules this - ceteris paribus - effect triggers a decrease in government consumption, government investment, and an increase in tax rates. Overall, those three fiscal effects counter the positive effect from higher anticipated technology and lead to an initial decrease of output.

Further, this implies that consumption and labor supply decrease. With less government investment firms increase investment activities by more than in the exogenous fiscal policy scenario.

If the shock materializes, the positive effects of higher technology materialize: output expands driving up consumption and reducing labor supply. Investment is further increased. Still, fiscal policy creates adverse effect towards the real economy due to its countercyclicality. Government consumption and investment decrease, while taxes further increase.

If the shock does not materializes, agents reverse plans and start to consume more and work more. Firms reduce investment activities. The government increases expenditures and lowers taxes given the low level of output and the falling level of debt. Debt increased on impact because lower labor supply and lower wages reduced the tax base. The adjustment to the steady state is quite persistent and takes several years.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wesselbaum, D. Expectation shocks and fiscal rules. Int Econ Econ Policy 16, 357–377 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-017-0389-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-017-0389-z