Abstract

This paper analyses the evolution of fiscal policy in central and eastern European countries during the EU accession process, testing for country and time specific effects. This is done by constructing Taylor-type policy rules and by calculating three measures of fiscal stance. A key finding is that the differences across countries are more significant than those across time. Baltic countries tended to have had tighter fiscal policy which responded to the output gap, larger central European countries had more lax (and increasingly lax) fiscal policies which were unresponsive to the output gap. These differences correlate closely with cross-country differences in exchange rate regimes and no link is found to either spending composition or political variables. Taken together the results suggest that the exchange rate regime is by far the most significant determinant of fiscal performance. These results suggest that the “soft power” of the prospect of EU entry did not act as a spur to greater fiscal discipline and that higher budget deficits in recent years cannot be blamed on costs of accession.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Better policymaking and institutional reforms are often cited as key benefits of closer European integration. The experience of the EU expansions to the South and to the East provides compelling evidence for the accession process as an impetus for rapid and far reaching institutional reform in states seeking EU membership. On the economic front, as Berger et al. (2007) note, one of the strongest arguments for an early enlargement of the EU to Central and Eastern Europe was that the accession process would provide an external anchor for macroeconomic policies.

In addition, the run-up of Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) was also associated with major changes to policymaking. In the 1990s, following the signing of the Maastricht Treaty, the goal of EMU membership provoked strenuous efforts to meet the strict criteria governing entry. Meeting the inflation and exchange rate criteria required a substantial reduction in inflation rates in many countries, and on the fiscal side the need to comply with the debt and deficit criteria of the Maastricht Treaty led to a concerted and historically exceptional period of fiscal retrenchments across many countries.Footnote 1

This paper analyses whether the recently completed accession process fostered a similar improvement in fiscal policymaking alongside the political and institutional reforms already mentioned. This “accession period” is defined to be from 1996 to 2004. By 1996, all aspiring members the bulk of reforms concerning privatisation, property rights, banking and other market institutions had been made and all eight countries had lodged applications to become accession candidates. This process concluded on May 1 2004 with the full accession of 8 New Member StatesFootnote 2 (NMS) from central and Eastern Europe.

There are no fiscal, monetary or exchange rate criteria for joining the EU. The only economic criteria are a functioning market economy plus commitment to the single market for labour, goods and capital. However, all the NMS are committed to joining the Euro as part of the accquis communitaire. This means that unlike the original Maastricht signatories, the accession phase and the run-up to EMU membership may not be two distinct and very separate epochs. For the NMS these two epochs will overlap to a greater or lesser extent, depending on the speed with which policymakers target membership of the single currency. Thus one might expect so see some of the economic policy gains associated with the run-up to EMU occurring prior to May 1st 2004.

Previous theoretical and empirical work suggests various factors which may have influenced fiscal policy in NMS between 1996 and 2004. Empirical work on the first wave of EMU entrants (von Hagen et al. 2004; Hughes Hallett and Lewis 2007) suggest there was a marked improvement in fiscal discipline in the run up to EMU, followed by a loosening after EMU entry was assured. Smaller countries tended to make greater efforts to consolidate than larger countries, which is generally attributed to the fact that smaller countries have less political power. This means that they are easier to exclude from the initial union, and, after joining, are easier to take sanctions against, which makes threatened punishments for fiscal laxity more credible.

This was similar to the argument advanced by Berger et al. (2007) who find a significant loosening in the larger central European economies fiscal policy post-1999, once they believed their membership was assured. These authors’ preferred explanation is that the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland were of greater geopolitical importance, and that having joined NATO, they believed they could not be excluded by the EU; whereas the Baltic states had to maintain discipline, because their lesser geopolitical importance made the threat to exclude them credible.

A well developed strand of literature on exchange rate regimes (see for example, Canzoneri et al. 1998) suggests that currency boards or hard pegs are only successful if fiscal policy is sustainable and thus governments are “forced” to run sound fiscal policies.Footnote 3 The argument is that if a currency board works successfully, then the hands of the monetary authorities are tied, and therefore, in the language of Sargent and Wallace (1981), there is “monetary dominance.” Fiscal authorities do not believe they will be bailed out by looser monetary policies, and are hence constrained from running up unsustainable deficit and debt paths.

These considerations suggest a natural split between the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) and the large central European countries—Large Hapsburgs—(Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland). The Baltic states have are characterised by fixed exchange rate policies, although the institutional arrangements and the currency to which they are fixed has varied across time and between countries.Footnote 4 The Hapsburgs have followed a variety of looser exchange rate regimes. In addition, within-group trading patterns, linkages to the Former Soviet Union as well as country size, suggest a natural division between the Baltics and Large Hapsburgs. Such a distinction is also drawn elsewhere in the literature, see for example Hughes Hallett and Lewis (2007), (Kopits and Székely 2003). A third group of Small Hapsburgs (Slovakia and Slovenia) is also identified—who, like the Baltics are of small size, but who are more similar to the bigger Hapsburgs in economic terms. Accordingly, this geographic classification is used alongside time specific variables as a potential determinant of fiscal policymakers behaviour.

The paper is organised as follows: Section 2 considers fiscal policy in terms of a Taylor-type rule, where fiscal policy responds to the output gap, adding in additional variables to capture regime effects. Section 3 examines the problem of sustainability and debt dynamics more explicitly, deriving measures of fiscal stance directly from the theory of sustainable fiscal policy. In Section 4 the composition of government spending is examined as a possible explanation for the differences across countries and over time. Section 5 concludes.

2 Fiscal policy rules

In this section fiscal policy is described by means of a simple rule, analogous to the Taylor Rule in the monetary policy literature, where the observed budget deficit is given as a function of the output gap.Footnote 5 This gives a measure of the pro- or counter-cyclicality of fiscal policy, and the extent to which fiscal policy is geared towards stabilising output.

Kattai and Lewis (2004) estimate such country-specific equations, but with a maximum of eight observations per country, only two parameters—an intercept and output gap co-efficient—may be estimated. To test for the impact of other variables such as country size, time effects, political factors etc requires the pooling of data across countries to conserve degrees of freedom. Pooling the data into a single sample (but allowing for fixed or random effects) is a widely used methodology in studies aiming to quantify such other influences on fiscal policy (See for example Turrini and In ’t Veld 2004; Berger et al. 2007).

The data are taken from Eurostat, supplemented where required by data from the IMF’s International Financial Statistics Database. Full details of the dataset used are given in the Appendix. The principal reasons for this choice were first, that it was these figures (rather than those of the IMF or another agency) that would be the figures utilised by European Union agencies monitoring the economic development of CEECs and second, that using a different dataset to Berger et al. (2007) provides the opportunity to see if their results are robust to a different data source.Footnote 6

2.1 Econometric methodology

In this section Taylor-type fiscal rules are estimated. The standard form of such rules is:

Where d is the deficit ratio, \( \widehat{y} \) is the output gap, and z is a vector capturing country-group and time specific effects. The methodology utilised is instrumental variables regression, where the money supply, inventories and gross fixed capital formation and its own lag are used to instrument the output gap.Footnote 7 To capture time effects, a pre-1999 time trend (equal to 0 from 2000 onwards) is included as are a post-1999 dummy and a post-1999 time trend. This corresponds to the date at which the Large Hapsburgs joined NATO, considered by Berger et al. (2007) to be the point at which these countries felt EU accession was assured.Footnote 8 Diagnostic tests also support the choice of 1999 as a “focal year” for time effects.

To account for country differences the sample is split up into the three groups described above, and experimented and both fixed and random effects were experimented with to capture country specific effects.Footnote 9 As an experiment economic variables expressed as ratios to potential as well as actual GDP were also used, but no differences were found between the two sets of results. The regression results (using economic variables as a percentage of actual GDP) are shown in Table 1.

The results suggest a marked difference between the three groups. The output gap is only significant for the Baltic states, suggesting that in the large and small Hapsburgs fiscal policy is not used for stabilisation purposes. This could reflect the fact the Baltics have surrendered monetary policy to maintaining a fixed exchange rate, and so fiscal policy is the only instrument left for stabilisation, whereas countries with more flexible exchange rates are using monetary policy to stabilise and thus use fiscal policy for other objectives.

The time dummies also reveal a post-1999 fiscal expansion of around 1% per year in the Large Hapsburgs, and a smaller contraction in the Small Hapsburgs. This is consistent with the view that smaller countries made efforts to consolidate fiscal policy prior to EU entry, whereas larger countries felt the pressure had eased once their accession was perceived to be secure. However, there is some evidence of an expansion in the Baltic states post 1999, although only for the fixed effects regression, and with a lower significance level. This could well be explained by the observation that following the budget deficit rise in response to the 1999 Russian crisis, Lithuania and Latvia did not fully recover their budgetary position in the upswing (See the graphs of fiscal policy stance or the figures in Kattai and Lewis (2004) for a demonstration of this point).

There is no significant role for interest rates in the Baltics or Smaller Habsburgs, suggesting that the falling interest rate burden in the latter was simply used to expand the primary position. The co-efficient sign in the Large Hapsburgs random effects regression is implausibly high, suggesting that it could reflect the unsuitability of treating Slovenia and Slovakia as a homogenous group. This may also explain why the constant term is not significantly different from zero in this group.Footnote 10

Lastly, the constant term is only significant for the Large Hapsburgs—equal to some 3.6% per year, meaning that the bulk of the difference in fiscal performance between the Baltics and Large Hapsburgs was constant across the sample period. The post 1999 loosening only explains a small fraction of the difference between the groups, suggesting that some other factor must have been at work.

In addition to the variables shown in Table 1, a wide variety of other variables which may affect fiscal policymaking were also experimented with, such as the electoral cycle, population, decentralisation of government etc. However, none of these country specific factors turned out to be significant. As a robustness check the regressions were repeated with the output gap replaced by economic growthFootnote 11 on the right hand side. The results produced were similar—the only difference being that the expansion in the Baltic states showed up in the step dummy, rather than in the post-1999 trend.

3 Fiscal stance and fiscal sustainability

The previous section analysed fiscal policy in terms of a simple reaction function. In this section, a different question is considered, namely the sustainability of deficit and debt ratios over time. As several authors have pointed out,Footnote 12 the faster growth and nominal appreciation experienced by CEECs means that they can run larger deficits than Western European nations, without fiscal policy becoming unsustainable—indeed a structural budget deficit may, under certain circumstances, be compatible with a stable or even falling debt ratio. In addition, the burden of interest payments on outstanding debt could be an important determinant of fiscal policy. A falling interest rate burden creates a dividend which can be used either to run primary surpluses (and hence reduce the debt ratio) or to permit a looser primary balance.

Accordingly, in this section the focus is shifted from budget deficits, to measures of fiscal stance which are explicitly derived from the economic theory of sustainable fiscal policy. Specifically, the sustainability of fiscal policy derived theoretically from the relationship between interest payments on the existing debt stock, economic growth, inflation, alongside the primary and total budget balance.

To do this, three measures of fiscal stance are constructed. In each case, the measure of fiscal stance is obtained by taking the difference between actual fiscal policy and the policy implied by three hypothetical benchmarks:

-

(a)

The primary surplus is just sufficient to cover interest payments (i.e. the total deficit is zero)

-

(b)

The primary surplus is sufficient to cover interest payments over the course of the cycle (but not necessarily in each year)

-

(c)

The primary surplus ensures that the debt ratio remains stable.

For a full derivation of the benchmarks, see the Appendix. For now it can be noted that the third measure is a more “liberal” measure than the others, because it implies a constant debt ratio, as opposed to a steadily declining debt ratio.Footnote 13 In addition, the measures may give quite differing pictures of fiscal position—for example, if a government is relying on fast growth and inflation to pay down its debt, then they will perform well on indicator (c), but poorly on indicators (a) and (b). Thus considering all three measures gives a better picture of how fiscal policy is evolving.

At this juncture it is necessary to have data for debt ratios and interest payments, as well as taxes and revenues. In the case of Slovakia and Slovenia, observations of all these variables are not available throughout the period, and so these countries are dropped from the analysis. For the other six countries, the dataset is broadly adequate.Footnote 14

These indicators can be used in two ways. First, they can be plotted for each country over time for visual inspection. This can be a useful tool in small datasets—since econometric tests have low power, the trained eye may pick up what formal analysis cannot. Second, these fiscal policy indicators are used as variables in econometric analysis.

3.1 Fiscal policy by country

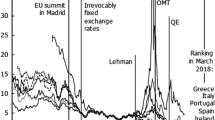

In what follows, the fiscal policy measures for each country are graphed, grouping the nations into Baltics and Large Hapsburgs as before. Figure 1 shows the Baltics, Fig. 2 the Large Hapsburgs. Where debt or interest rate data is added from IMF dataset, this is indicated by a break in the line.

The y-axis measures fiscal stance as a percentage of GDP. A positive number corresponds to an expansionary stance, a negative number represents a contractionary stance. All three measures derived above are graphed, t−g = z is the stance relative to the benchmark where the primary surplus covers interest payments in each and every year, t−g = z l/t where the benchmark is that the primary surplus covers interest payments over the cycle, and b stab’y where the benchmark is a stable debt ratio over time.

The three graphs reveal a relatively consistent picture across all three countries. The congruence of the three indicators reflects the low debt ratios of these countries—hence inflation and growth effects on existing debt stocks are small. Prior to 1999 fiscal policy is broadly consistent with stable debt ratios. In 1999, the Russian crisis causes a sharp fall in output, and a corresponding rise in deficits. In subsequent years, fiscal stance reverts to its pre-shock state, although Latvia and Lithuania show some sluggishness in recovering their budgetary positions during the upswing.

In comparison with the Baltics, fiscal policy is significantly looser in all three countries. In the early part of the accession period, inflation helped to keep debt ratios down in Poland and Hungary, but as inflation slowed debt dynamics worsened. However, this fall in inflation cannot account for the fiscal slippage post-1999, because all three fiscal policy indicators rise in this period, indicating that it was deteriorations in the primary balances that were to blame rather than slow growth or lower inflation.

3.2 Fiscal policy by country group: a cross-sectional analysis

Next, fiscal policy stance is analysed using each of the derived fiscal policy measures as a dependent variable. As in the last section, the data are pooled according to the country groups, the only difference being that the Small Hapsburgs are excluded due to data problems. To do this, regressions are estimated of the form:

where fp corresponds to the fiscal policy measure for country i at time t, and z corresponds to a vector of possible explanatory variables. Time specific variables are included as before, and also include interest payments, following Berger et al. (2007), to see if the burden of debt repayments has an effect on fiscal policy. As with the earlier estimations, political variables were originally included, but found to be insignificant.

The results are shown in Table 2.

For the Baltic states, there is some evidence of a fiscal expansion in 1999—but this is probably due to the budgetary consequences of the Russian Crisis. Moreover, it can be seen that fiscal policy gradually tightened after 1999. However, for the large Hapsburgs, a quite different picture emerges. For these nations, fiscal policy gets looser after 1999, by around 0.9 percentage points of GDP per year. Cumulatively, this implies that fiscal policy was around 4.5% of GDP looser on the date of accession than it was in 1999.

These results reveal a clear difference between the country groups. The constant term shows that other things being equal, the Baltic nations had a more restrictive fiscal policy stance (as shown by the constant term) than the Large Hapsburgs. Moreover, comparing the post-1999 coefficients, it can be seen that fiscal policy tended to tighten in the Baltics, whereas it loosened in the Large Hapsburgs (Table 3).

4 De-composition of deficits by spending type

In this section the focus is on the expenditure side, because several contributions—theoretical and empirical—highlight link between expenditure (as opposed to the revenue side) and deficits. First, it has been noted by Buiter and Grafe (2004) and others, that given the higher economic growth and higher inflation implied by the catch-up process, allied with the low levels of public capital in many new EU members, there is a rationale for running budget deficits, if those deficits are used to finance public sector investment. In other words, as argued by Blanchard and Giovazzi (2004), investment should be treated differently to other categories of government spending in assessing fiscal discipline. A disaggregated analysis shows whether higher deficits reflect higher levels of investment, or simply higher levels of other items of spending. Second, the recent literature on public finances suggests that the composition of public spending affects fiscal stance (Table 4). For example von Hagen et al. (2002), find that the success of fiscal consolidations is related to whether expenditure or revenues are targeted, and by what sort of expenditure is cut.

4.1 Linear regression analysis

To analyse the relationship between the deficit ratio and the type of spending, two regression equations are estimated:

Where E i and s j correspond to the proportion of GDP spent on, and the share of total government spending devoted to, expenditure type j. The six types of government spending used are transfers in kind, cash transfers, government wages and salaries, gross fixed capital formation, collective consumption and subsidies.

Shares of government spending are utilised so as to come up with a measure which is independent of the size of the government sector. One may argue that the size of the government sector is determined by other factors, not least social preferences, and therefore, what matters is the proportion of collective expenditure given to various uses. On the other hand, the regression using shares of GDP has the advantage that it directly captures the effects of varying the level of each component. For instance, one may argue that the relative shares of different components in total government expenditure are largely independent—in the sense that the choice of how much public investment is independent of the level of say subsidies. In addition, total government spending data is not available for all countries over the sample period, so expressing variables as a ratio to GDP allows the inclusion of more observations.

These equations can then be used to test various hypotheses about budget deficits. If higher budget deficits simply reflect (say) greater capital investment, then one would observe a negative coefficient on capital investment. On the other hand, if one observes no significant coefficients, then it means there is no linkage between the composition of budget deficits and their size, in which case, it can be concluded that differences in budget deficits are the result of different intertemporal preferences, political structures or some other unobserved variable.

The regression using shares of government spending has 24 observations spanning four countries—Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland, therefore, it should be borne in mind that the results are derived from using only half of the countries in the sample.

The regression using shares of GDP is estimated for two different samples, one using the most possible observations, and one using the same observations as the shares of total government spending regression. This enables a direct comparison between the results to be made, by estimating two equations over the sample set of observations. Results are presented in Table 4.

These results indicate that the only significant compositional effect comes from the subsidy components which enter with a strongly negative sign. This implies that higher spending on subsidies is associated with higher deficits—specifically that a 1% rise in the share of subsidies in government spending is associated with a worsening fiscal position of around 1.5% of GDP. One possible explanation of this is that both are symptoms of a common problem—if political and institutional structures are such that governments are unable to resist political pressure for subsidies, they are also unable to resist political pressure for greater spending and/lower taxes and hence find it harder to consolidate public finances. On the other hand, there is no evidence that higher deficits are associated with higher investment, transfer payments, transfers in kind, collective consumption or government employees.

Various other specifications were estimated—breaking the data down into the same country specific groups as in Section 3, and using primary as well as total balances. In each case, no different or significant results were found.

5 Conclusions

Section 2 examined fiscal policy on a country by country basis. This analysis revealed a marked contrast between different countries. A key finding is that fiscal policy was generally more expansionary in the Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary. In addition, for the latter two, debt ratios were moderated initially by higher inflation, and once inflation slowed, debt ratios began to rise more sharply. The Baltic nations tended to follow less expansionary fiscal policies, apart from during 1999 when there was a strong expansionary response to the Russian crisis. However, after 1999, fiscal policy returns to more or less the same position as prior to the crisis.

Section 3 tested for time and regional specific effects. The finding was that there was a worsening of fiscal discipline post-1999 in the larger central European countries, which was not matched in the Baltic states, or in Slovakia and Slovenia. This finding is consistent across a variety of measures and provides further empirical support for the hypothesis of Berger et al. (2007) that fiscal discipline became looser once EU membership was secured. However, these results could simply be the result of the budgetary costs of the accquis communitaire. That said, this explanation of deficits is troubling because it would appear that from a disaggregated analysis these higher deficits cannot be explained by higher public investment, and these effects do not show up for other member states, even those with lower levels of GDP. The Baltic states tended to run tighter fiscal policies, perhaps as a consequence of the greater need for discipline under a currency board. The analysis of Section 2 suggested that inflation was being used to reduce debt ratios in many larger central European economies, an option that is largely ruled out under a currency board.

In Section 4, it was found that there is a relatively weak correlation between the type of government spending, and deficits. On the one hand, this means that higher deficits cannot simply be attributed to greater investment, but equally it suggests that fiscal discipline is not strongly associated with targeting any one particular component. It was found that subsidies was correlated with deficits, suggesting that higher spending on subsidies was associated with looser fiscal policies. In addition there was little evidence of cyclical influences on each category.

Overall, the evidence suggests that accession process did not exert widespread fiscal discipline on applicant countries during the accession process. There was a loosening of fiscal policy in the large central European countries post-1999 which could be interpreted as a relaxation of stance after the discipline provided by the implicit threat of exclusion from the EU was lifted. However, the results indicate that the loosening began well before 1999, suggesting that the subsequent loosening was the continuation of the previous trend, rather than a new innovation.

Far more striking than the temporal effects are the differences between countries. Testing for the effect of various political variables or the composition of spending yielded no significant explanatory results. Rather, fiscal discipline appears to be much more closely correlated with cross-country effects, and in particular the currency board/tight peg arrangements of the Baltic nations. It could be argued that what is being picked up here is a “small country” effect, rather than an exchange rate regime effect.Footnote 15 This is difficult to test for directly since there are no observation of a large country with a currency board, or of a Baltic country with a floating exchange rate. However, it should be noted that with the possible exception of Poland, none of the central European countries are particularly large by GDP or population size.

In addition it is difficult to blame larger deficits on the costs of the accession process, since there was no uniform loosening of fiscal policy across all countries. If anything, one might expect the Baltic nations to have had higher costs, since they were starting from lower levels of GDP and with fewer market institutions in the early 1990s.

It could be argued that the real spur to fiscal discipline is provided by EMU rather than EU membership, since it is only the former which imposes binding numerical entrance criteria for fiscal variables. The effects of this would be almost observationally equivalent in this sample, because two of the three nations targeting a swift entry to the Eurozone are the Baltic states of Lithuania and Estonia. However, it is difficult to believe that a desire for early EMU entry can explain the observed differences in fiscal discipline over the sample period for the simple reason that for much of this time, EU entry, let alone EMU entry was not assured for either Estonia or Lithuania. A more plausible explanation is that Estonia and Lithuania were candidates for early entry on account of their currency boards which meant that—(a) pushing for early Euro entry carried no opportunity cost in terms of lost monetary policy autonomy and (b) public finances were already in a reasonably good shape.

In sum, the accession process did not produce any uniform effects on fiscal policy over the eight countries considered here. The “soft power” of the prospect of EU membership did not discipline fiscal policies. As with previous expansions of the EU, it is the specific numerical criteria required for EMU entry, rather than EU membership itself which appear to foster fiscal discipline.

Notes

The eight countries were: The Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. Malta and Cyprus also joined on this date but are not considered here as the focus is on Central and Eastern European countries.

However, whether the threat of exchange rate regime collapse is sufficient to discipline fiscal policy is a separate issue. Recent empirical work (e.g. Tornell and Velasco 1995 and Sun 2003) has suggested that tight exchange rate regimes are not, in and of themselves sufficient to discipline fiscal policy.

The Estonian Kroon has operated under a currency board since its inception in 1992—first backed by the German Mark, and latterly the Euro. Lithuania operated a currency board backed by the US dollar until January 2002, and subsequently the Euro. The Latvian Lats was pegged first to the IMFs Special Drawing Right, and, from 2005 to the Euro.

See Balabriga and Martinez Mongay (2002) for a detailed justification of the use of fiscal “Taylor Rules” to describe the behaviour of fiscal policymakers.

In the context of formerly centrally planned economies, there are many methodological issues concerning the compilation of data on government finances which mean that the different statistical sources may yield significantly different raw data.

The data for all the variables used as instruments are taken from the IMF’s IFS database.

(Kopits and Székely 2003) also highlight this year as a potential structural break.

There is no consensus between similar studies on whether to use fixed or random effects. To preserve generality, enhance comparability, and to demonstrate that the results are robust to estimation method chosen, both results are reported.

The t-statistic turns out not to be significant, due to high variance of the co-efficient estimate rather than an estimated co-efficient close to zero.

This was the approach used by Berger et al. (2007).

If the real debt stock is held constant, then under positive economic growth the debt:GDP ratio will decline over time.

The IMF’s IFS database was used to replace the missing observations for debt and interest rate figures. As a consequent the debt stability benchmark (but not the others) is calculated using data drawn from two different accounting methodologies. However, a comparison between the datasets for years where both record observations suggests that the methodologies produced very similar figures. A further check was made comparing the different fiscal policy measures for consistency. These suggested that the additional degrees of freedom gained by supplementing the data with IMF figures outweighed any possible problems induced by mixing the data. Using IMF data for taxes, revenues and deficits however does affect the other two fiscal policy indicators. Since policymakers in NMS use EU figures, it seemed reasonable to use EU data wherever possible for this analysis.

For example, von Hagen et al. (2004) find greater discipline in smaller EU15 countries.

From here on, time subscripts are suppressed for simplicity.

References

Balabriga F, Martinez Mongay C (2002) Has EMU shifted fiscal policy? Economic Papers 166, European Commission

Berger H, Kopits G, Székely P (2007) Fiscal indulgence in Central Europe: loss of the external anchor? Scott J Polit Econ 54(1):116–135

Blanchard O, Giovazzi F (2004) Improving the SGP through a proper accounting of public investment. CEPR Discussion paper 4220, Centre for Economic Policy Research, London

Buiter W, Grafe C (2004) Patching up the pact. Econ Transit 12(1):67–102

Canzoneri MB, Cumby RE, Diba B (1998) Fiscal discipline and exchange rate regimes. CEPR Discussion Paper 1899

Hughes Hallett A (2002) Pre-committing monetary policies without fiscal commitment. Could fiscal austerity have saved Argentina? Mimeo, Vanderbilt University

Hughes Hallett AJ, Lewis JM (2007) Debt, deficits, and the accession of the new member States to the Euro. Europ J Polit Economy (in press)

Kattai R, Lewis J (2004) Hooverism, hyperstablisation or halfwayhouse? Fiscal policy in the Central and Eastern Europe. Bank of Estonia Working Paper Series

Kopits G, Székely I (2003) Fiscal policy challenges of EU accession for the baltics and Central Europe. In: Trumpel-Gugerell G, Mooslechner P (eds) Structural challenges for Europe. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK

Sargent K, Wallace N (1981) Some unpleasant monetarist arithmetic. Q Rev—Fed Reserve Bank Minneapolis 5:1–17 (Fall)

Sun Yan (2003) Do fixed exchange rates induce more fiscal discipline? IMF Working Papers 03/78, International Monetary Fund, Washington DC

Turrini A, In ’t Veld J (2004) The impact of the EU fiscal framework on economic activity. Mimeo, European Commission

Tornell A, Velasco A (1995) Fiscal discipline and the choice of exchange rate regime. Eur Econ Rev 39:759–770 (April)

von Hagen JA, Hughes Hallett A, Strauch R (2002) Budgetary consolidation in Europe: quality, economic conditions and persistence. J Jpn Int Econ

von Hagen JA, Hughes Hallet AJ, Lewis JM (2004) Fiscal policy in Europe, 1991–2003: an evidence-based analysis. Centre for Economic Policy Research, London

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to two anonymous referees for helpful comments. The author is grateful to Bank of Estonia’s research department where the bulk of the research for this paper was carried out during two 6-month stints under the auspices of their visiting researcher programme. The responsibility for any remaining errors or omissions lies entirely with the author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of De Nederlandsche Bank or the Bank of Estonia.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 A.1 Dataset

The primary data source is Eurostat. Where necessary this is supplemented by data from national statistical agencies. The dataset contains variables for all EU member states, acceding and candidate countries as well as Japan, Norway and the US. They are comparable across countries and utilize the ESA95 methodology. The data is used by the European Commission in the preparation of its reports, including European Economy and its assessments of each member states convergence programme.

Eurostat data was used wherever possible, and supplemented with IMF data where no comparable figures existed. The additions from IMF data are the following:

-

Total Deficits/Interest Payments: HU 1996–2001, SI 1996–1998

-

Debt:GDP Ratio: CZ, EE, LV, LT, HU, PL, SK 1996, SI 1996–1997

-

Taxes & Govt Spending: EE, HU, SK, SI 1996–2000

1.2 A.2 Derivation of fiscal benchmarks

This paper uses the same analytical framework for the dynamics of debt in relation to economic growth following Hughes Hallett (2002). The starting point is the government’s budget constraint at time t, expressed in real terms:

Suppose the government debt takes the form of one period bonds. B. In any given period, government spending G plus the costs of servicing the stock of debt, B, accumulated in previous periods must be less than or equal to the sum of tax revenue, T, plus the current period’s debt.

Dividing both sides by output gives:

where lower case letters denote ratios of variable to GDP, and x is the growth rate of nominal GDP, and where \( Y_{t} = {\left( {1 + x_{t} } \right)}Y_{{t - 1}} \). This then yields the following equation for the dynamics of the debt burdenFootnote 16:

x can be decomposed into the sum of real GDP growth, γ, and the rate of inflation, π. Similarly, the nominal interest rate can be decomposed into the sum of the real interest rate, r, and the rate of inflation. Making those substitutions, Eq. 3 can be re-written in real terms.

Inserting \( {\mathop b\limits^ \cdot } = 0 \) into Eq. 4 and re-arranging, gives the condition for debt ratio stability:

From this analysis three “benchmark” fiscal policies can be generated and by comparing actual fiscal policy with these benchmarks, three measures of fiscal stance. The first benchmark is where the government runs a primary surplus sufficient to cover all interest payments:

This can be modified in order to take into account fluctuations in the rate of output. Assume that the government increases real expenditures in line with long-run economic growth each year, setting a (time invariant) average tax rate consistent with running a primary surplus equal to interest payments over the cycle. This yields:

where γγ is the long rate rate of growth obtained by calculating the average compound growth rate over the sample.

The last benchmark is that of debt stability, this is given by Eq. 5

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lewis, J. Fiscal policy in central and Eastern Europe: what happened in the run-up to EU accession?. IEEP 4, 15–31 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-007-0080-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-007-0080-x