Summary

Background

Patients with end-stage liver disease can only be cured by liver transplantation. Due to the gap between demand and supply, surgeons are forced to use expanded criteria donor (ECD) organs, which are more susceptible to ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI). Therefore, enhanced storing techniques are required. Machine perfusion (MP) has moved into the spotlight of research because of its feasibility for investigating liver function prior to implantation. However, as the perfect MP protocol has not yet been found, we aimed to investigate the potential of sub-normothermic (SN)MP in this field.

Methods

Non-allocable human livers were subjected to 24 h of SNMP at 21 °C after delivery to the study team. Perfusion was performed with Custodiol® (Dr. Franz Köhler Chemie, Bensheim, Germany) or Belzer MPS® (Bridge to Life Europe, London, UK) and perfusate liver parameters were determined. For determination of biliary conditions, pH, glucose, and HCO3- levels were measured.

Results

Liver parameters were slightly increased irrespective of perfusate or reason for liver rejection during 24 h of perfusion. Six livers failed to produce bile completely, whereas the remaining 10 livers produced between 2.4 ml and 179 ml of bile. Biliary carbonate was increased in all but one liver. The bile-glucose-to-perfusate-glucose ratio was near 1 for most of the organs and bile pH was above 7 in all but one case.

Conclusion

This study provides promising data on the feasibility of long-term SNMP as a tool to gain time during MP to optimize ECD organs to decrease the gap between organ demand and supply.

Long-term (24 h) sub-normothermic liver machine perfusion seems to be possible, although some adjustments to the protocol might be necessary to improve the general outcome. This has so far been shown for normothermic machine perfusion, bearing some drawbacks compared to the sub-normothermic variant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Liver transplantation (LT), the best option to improve a patient’s quality of life in a broad spectrum of end-stage liver diseases, has evolved tremendously during recent decades. With the steadily growing gap between supply and demand, the use of expanded criteria donor (ECD) organs as well as new preservation technologies is gaining importance [1]. Static cold storage (SCS) is, due to its cost effectiveness and simplicity, still the method of choice when it comes to organ preservation. In the past few years, machine perfusion (MP) has stepped into the spotlight in that very field [2,3,4]. Especially for the use of ECD organs, MP improves characterization of the donor organs prior to implantation [5]. A variety of methods to estimate liver function during MP [6] are available right now, making it a very promising tool to narrow the gap between supply and demand.

To date, MP protocols vary widely according to the applied temperature, making it very hard to decide on the “optimal” protocol. While the higher temperatures (around normothermia of 37 °C) result in bile production and more physiologic metabolism [7,8,9], the main drawback of those so-called normothermic protocols is the vulnerability of the organ to machine malfunction leading to maximum ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI) [8]. Lower perfusion temperatures (hypothermia between 4 and 10 °C) decrease the vulnerability to IRI linked to the threat of machine malfunction [10], thus limiting the extent of metabolism and bile production limiting the validity of the classical liver parameters determined during MP [8, 11, 12]. To find a balance between those drawbacks, sub-normothermic machine perfusion (SNMP between 15 and 30 °C) seems to grant a practicable means, by reducing IRI while granting liver metabolism in an acceptable fashion [13, 14]. In this study we used SNMP in combination with two different types of perfusate to set up an MP protocol and investigate the changes in liver parameters during a 24-hour period of SNMP after varying periods of SCS.

Methods

Sixteen non-allocable human livers, rejected for transplantation by all centers the organs had been offered to, were included in this study. The institutional ethics committee of the Medical University of Graz (30-493 ex17/18) approved the use of non-allocable livers.

Organ preparation and back table procedure

After procurement, the organs were used for MP after SCS in Custodiol® (Dr. Franz Köhler Chemie GmbH, Bensheim, Germany) as soon as the study team received the organs from the clinical team. For MP, the hepatic portal vein and hepatic artery were cannulated (25 F portal or 8 F arterial cannula; Organ Assist, Xvivo, Groningen, Netherlands) by fixation with a Vicryl (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson Medical N.V., Belgium) ligature. To collect the produced bile, the common bile duct was cannulated by use of a polyurethane Nutrifit feeding tube (8 F, 125 cm length; Vygon, Paris, France), which was also fixed by means of a Vicryl ligature. Immediately prior to perfusion start, the organ was weighted and subsequently flushed with 2 L of 4 °C Custodiol®.

Sub-normothermic machine perfusion and sampling

For liver perfusion, the Liver Assist® (LiA) machine was used in combination with the LiA disposable set (Organ Assist). The 24-hour perfusion protocol was adapted from [15]. The system was pre-filled with 4 l of Custodiol® or Belzer MPS® (Bridge to Life Europe, London, UK) supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and amphotericin B (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vienna, Austria) to a final concentration of 40,000 U/l, 0.04 mg/l, and 1 mg/l, respectively. Machine setup was accomplished according to the manufacturer’s protocol, with the temperature set to 21 °C and oxygenation with 100% O2 at a constant flowrate of 1 l/min. After 6 h of perfusion, 50% of perfusate was replaced by the same type of fresh perfusate to dilute potentially harmful substances from the circulation.

Sampling (perfusate and tissue) was performed hourly for the whole 24 h of MP. Perfusate samples were shock frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further use. Bile samples were processed in the same way as perfusate samples if bile was produced in a sufficient quantity.

Liver-specific parameters

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), γ‑glutamyltransferase (GGT), alanine phosphatase (AP), lactate (LAC), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) were determined from frozen perfusate samples by a cobas® 8000 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) with reagents from the same manufacturer. Since the respective methods were not validated for this extraordinary sample matrix, we evaluated the analytical performance using a standard addition protocol.

A blood plasma pool was constituted from several anonymized leftover samples from laboratory routine. The concentrations of ALP, ALT, AST, GGT, LAC, and LDH were determined as the means of fivefold serial measurement for each marker in both the plasma pool and the pure perfusion solute. Thereafter, pure perfusion solute was mixed with pooled plasma at different proportions (10 + 0, 9 + 1, 8 + 2, 7 + 3, etc.) and every marker was determined for every mixture ratio. We calculated the percentage recovery as the ratio of the measured to the expected result, a value between 85 and 115% was considered acceptable. The best recovery rates were seen for ALT (91–112%), AST (90–106%), and LDH (94–101%). For ALP (67–100%) and GGT (69–103%), recovery was worse at lower concentrations. Linear regression analysis revealed a predominantly negative constant bias for these two markers. Because we only performed longitudinal analyses, we did not exclude these markers from the study, since a constant bias does not tarnish the interpretation of dynamics over time.

Perfusate pH and glucose levels as well as bile pH, glucose, and HCO3− levels as measures of biliary epithelial integrity [16] were monitored on site by an ePOCT Analyzer (Siemens Healthcare, Vienna, Austria) in combination with BGEM test cards. Perfusate pH was adjusted by addition of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate solution.

Statistical analysis

Graphs were drawn by means of GraphPad Prism 9 for Windows (version 9.1.2, GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA) and data were compared by means of the Mann–Whitney U test. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Organs included

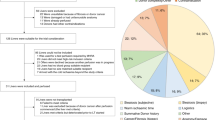

Sixteen non-allocable livers from 9 female and 7 male donors with a mean age of 66 years (range 44–81 years) were included into the study. The mean SCS time was 14 h 17 min (range 3–29 h 10 min). Donor characteristics, SCS time prior to SNMP onset, and the perfusate solution used for MP are listed in Table 1.

Liver parameters during SNMP

All liver parameter levels increased at different rates in SNMP, irrespective of the perfusate used, with LDH, AST, and ALT reaching statistical significance when changes in MPS were compared to changes in the Custodiol® group (Fig. 1b). A similar picture is observed when changes in liver parameters are grouped by reasons for rejection (cirrhosis, steatosis, other reasons as described in Table 1). The average slope depicts an increase at different rates in all liver parameters, irrespective of the state of the liver, but only for lactate did the differences reach statistical significance (Fig. 1a). The average amount of sodium bicarbonate added to sustain a stable, physiological pH was similar with respect to reason of rejection (median [Q1, Q3]: 205 ml [153 ml, 320 ml] liver rejected for other reasons, 175 ml [125 ml, 375 ml] steatotic livers, 290 ml [0 ml, 580] cirrhotic livers; n. s.), but was significantly higher in livers perfused with Custodiol® (median [Q1, Q3]: 365 ml [280 ml, 513 ml]) compared to Belzer MPS (median [Q1, Q3]: 140 ml [88 ml, 161 ml]; p = 0.0002). Liver parameters prior to start of SNMP (representing the enzymes produced during SCS), after 1 h of machine perfusion, and after 24 h of SNMP are listed in Table S1 and detailed information on changes over time are shown in Figures S1–S6.

Changes of liver parameters in perfusate during 24 h of sub-normothermic machine perfusion grouped by reason for non-allocability (a) and perfusate (b). Perfusates used are Custodiol® (CUST, Dr. Franz Köhler Chemie, Bensheim, Germany; n = 8); Belzer MPS (MPS, Bridge to Life Europe, London, UK n = 8). CIRR cirrhosis (n = 2), STEAT steatosis (n = 7), ELSE other reasons for rejection (n = 7), LAC lactate, GGT Gamma-glutamyltransferase, AP alkaline phosphate, Avge average. Horizontal lines represent the median of each dataset

In this study, six (one steatotic in Custodiol®; two steatotic, one cirrhotic, and two livers rejected for other reasons in the Belzer MPS group) out of 16 livers did not produce any bile during 24 h of SNMP. Among those livers producing bile, the total quantity varied between 2.40 and 179 ml (Custodiol®: average 43.69 ml; Belzer MPS: average 17.37 ml). In the hours prior to perfusate renewal at 6 h of SNMP, the average bile production was about 1.69 ml/h (Custodiol®: 2.16 ml/h; Belzer MPS: 0.59 ml/h) compared to about 1.43 ml/h (Custodiol®: 1.71 ml/h; Belzer MPS: 0.77 ml/h) between hours 7 and 24 of SNMP (Table 2). It seems that upon perfusion with Custodiol®, bile production during the first 6 h of SNMP was higher than in the later period, whereas upon perfusion with Belzer MPS, bile production seems stable over the whole period of SNMP. None of the reported differences in bile production reached statistical significance. The ratios of bile/perfusate glucose levels, a surrogate for bile duct injury [17], are close to 1 for all, except for two livers during the whole time of perfusion. The bile/perfusate glucose ratio for L5 is much lower, whereas the cirrhotic liver (L7) revealed a ratio of around 4. For all but one liver, bicarbonate levels increased over time at different rates.

Discussion

In this experimental study, we demonstrate for the first time that 24-hour SNMP of human livers is feasible. Although the classic liver parameters tend to increase during perfusion, the extent of increase varies widely because of the heterogeneity of groups. With respect to perfusion solution, it is not possible to pick the “most suitable” solution from the data in this study, as both used solutions have pros and cons in one parameter or another, as has also been discussed previously [18, 19]. If bile production is used as a measure of liver function, one might speculate that Belzer MPS is less suitable for liver SNMP than Custodiol®, as 5 out of 8 livers (62.5%) in that group failed to produce bile at all, whereas only 1 out of 8 livers (12.5%) in the Custodiol® group failed to do so.

It has been previously been reported that biliary pH as well as glucose and bicarbonate levels are markers for biliary injury in normothermic machine perfusion and that a high (close to 1) ratio of bile glucose to perfusate glucose levels is predictive for biliary complications [17, 20]. In our study, the ratios were around one for almost all livers, one even reaching a ratio of 4 and leading to the assumption that upon implantation, biliary complications might occur and an adaptation of the protocol might be inevitable in that context. Furthermore, it will be of interest for future projects to investigate if the predictive potential of that ratio holds true for SNMP conditions, as was published for normothermic conditions [17]. Biliary bicarbonate, as a surrogate for bile tract function described as the “bicarbonate umbrella” [20,21,22], increases in all but one liver, leading to the assumption that bile duct injury might not be as severe as indicated by the previously discussed ratio. This interesting topic needs further in-depth investigation to elucidate whether and to what extent SNMP might be able to resolve one of the main problems in liver transplantation.

Lower perfusion temperatures have been shown to be able to protect livers from injury [13, 23], but the field is wide and protocols are far from consistent [24]. As the metabolic activity of organs declines with a decrease in temperature, the gold standard liver parameters might not be the best surrogates to be looked at if it comes to estimation of liver function, but valid alternatives are coming up [25]. Herein, we found that liver function, mirrored by increasing levels of liver parameters, over the course of 24 h of SNMP seems to worsen only slightly, encouraging further research in the field to move towards the final goal to overcome organ shortage by re-conditioning or simply “storing” the organ with minimal damage until transplantation.

References

Bodzin AS, Baker TB. Liver transplantation today: where we are now and where we are going. Liver Transpl. 2018;24(10):1470–5.

Tingle SJ, Figueiredo RS, Moir JA, et al. Machine perfusion preservation versus static cold storage for deceased donor kidney transplantation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3:CD11671.

Czigany Z, Lurje I, Tolba RH, et al. Machine perfusion for liver transplantation in the era of marginal organs-new kids on the block. Liver Int. 2019;39(2):228–49.

Bruns H, Schemmer P. Machine perfusion in solid organ transplantation: where is the benefit? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2014;399(4):421–7.

Kvietkauskas M, Leber B, Strupas K, Stiegler P, Schemmer P. Machine perfusion of extended criteria donor organs: immunological aspects. Front Immunol. 2020;11:192.

Kvietkauskas M, Zitkute V, Leber B, et al. The role of metabolomics in current concepts of organ preservation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(18):6607.

Kataria A, Magoon S, Makkar B, Gundroo A. Machine perfusion in kidney transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2019;24(4):378–84.

Selten J, Schlegel A, de Jonge J, Dutkowski P. Hypo- and normothermic perfusion of the liver: which way to go? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;31(2):171–9.

Imber CJ, St. Peter SD, Lopez de Cenarruzabeitia I, et al. Advantages of normothermic perfusion over cold storage in liver preservation. Transplantation. 2002;73(5):701–9.

Petrenko A, Carnevale M, Somov A, et al. Organ preservation into the 2020s: the era of dynamic intervention. Transfus Med Hemother. 2019;46(3):151–72.

Fuller BJ, Lee CY. Hypothermic perfusion preservation: the future of organ preservation revisited? Cryobiology. 2007;54(2):129–45.

Jochmans I, Pirenne J. Graft quality assessment in kidney transplantation: not an exact science yet! Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2011;16(2):174–9.

Bruinsma BG, Yeh H, Ozer S, et al. Subnormothermic machine perfusion for ex vivo preservation and recovery of the human liver for transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(6):1400–9.

Tolboom H, Izamis ML, Sharma N, et al. Subnormothermic machine perfusion at both 20 °C and 30 °C recovers ischemic rat livers for successful transplantation. J Surg Res. 2012;175(1):149–56.

Bruinsma BG, Avruch JH, Weeder PD, et al. Functional human liver preservation and recovery by means of subnormothermic machine perfusion. J Vis Exp. 2015;98:52777. https://doi.org/10.3791/52777.

Op den Dries S, Sutton ME, Karimian N, et al. Hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion prevents arteriolonecrosis of the peribiliary plexus in pig livers donated after circulatory death. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e88521.

Matton APM, de Vries Y, Burlage LC, et al. Biliary bicarbonate, pH, and glucose are suitable biomarkers of biliary viability during ex situ normothermic machine perfusion of human donor livers. Transplantation. 2019;103(7):1405–13.

Adam R, Delvart V, Karam V, et al. Compared efficacy of preservation solutions in liver transplantation: a long-term graft outcome study from the European liver transplant registry. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(2):395–406.

Hameed AM, Laurence JM, Lam VWT, Pleass HC, Hawthorne WJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cold in situ perfusion and preservation of the hepatic allograft: working toward a unified approach. Liver Transpl. 2017;23(12):1615–27.

Westerkamp AC, Mahboub P, Meyer SL, et al. End-ischemic machine perfusion reduces bile duct injury in donation after circulatory death rat donor livers independent of the machine perfusion temperature. Liver Transpl. 2015;21(10):1300–11.

Hohenester S, Wenniger LM, Paulusma CC, et al. A biliary HCO3− umbrella constitutes a protective mechanism against bile acid-induced injury in human cholangiocytes. Hepatology. 2012;55(1):173–83.

Beuers U, Hohenester S, de Buy Wenniger LJ, et al. The biliary HCO(3)(−) umbrella: a unifying hypothesis on pathogenetic and therapeutic aspects of fibrosing cholangiopathies. Hepatology. 2010;52(4):1489–96.

Vairetti M, Ferrigno A, Carlucci F, et al. Subnormothermic machine perfusion protects steatotic livers against preservation injury: a potential for donor pool increase? Liver Transpl. 2009;15(1):20–9.

Schlegel A, Muller X, Dutkowski P. Machine perfusion strategies in liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2019;8(5):490–501.

Schurink IJ, de Haan JE, Willemse J, et al. A proof of concept study on real-time LiMAx CYP1A2 liver function assessment of donor grafts during normothermic machine perfusion. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):23444.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by B. Leber, S. Schlechter, J. Weber, L. Rohrhofer, and T. Niedrist. The first draft of the manuscript was written by B. Leber and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

B. Leber, S. Schlechter, J. Weber, L. Rohrhofer, T. Niedrist, A. Aigelsreiter, P. Stiegler, and P. Schemmer declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leber, B., Schlechter, S., Weber, J. et al. Experimental long-term sub-normothermic machine perfusion for non-allocable human liver grafts: first data towards feasibility. Eur Surg 54, 150–155 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10353-022-00756-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10353-022-00756-w