Abstract

Vietnam is home to four species of otters, and while population numbers are unknown, they are thought to be rare and in decline. Studies on the illegal otter trade in Asia have shown Vietnam to be a key end use destination for illegally sourced live otters for the pet trade and otter fur for the fashion industry. This study focused on the otter trade in Vietnam through seizure data analysis and an online survey, revealing the persistent trade of otters in Vietnam in violation of national wildlife laws and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). We found a substantial quantity of otter fur products for sale though CITES permits for such products were lacking, indicating illegal origins. Similarly, all four species of otters are protected in Vietnam, yet they were openly available for sale online in violation of national wildlife laws. Clearly, the online trade of wildlife and wildlife products in Vietnam requires greater monitoring, regulation, and enforcement to prevent the advertising and trade of illicit wildlife. In-depth scrutiny of online sellers and product sourcing is particularly warranted. To support enforcement efforts, revision of policies and laws is needed to hold social media and other online advertising companies accountable for enabling the illegal trade of wildlife.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

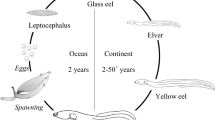

There are 13 species of otters globally, five of which are found in Asia: the Eurasian otter Lutra lutra, the hairy-nosed otter Lutra sumatrana, the small-clawed otter Aonyx cinereus, the smooth-coated otter Lutragale perspicillata, and the sea otter Enhydra lutris (although this species occurrence in Asia is limited to the eastern coastal areas of the Russian Federation and northern Japan). Based on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, all five species are at risk of extinction with the Eurasian otter assessed as near threatened, the small-clawed otter and smooth-coated otter assessed as vulnerable, and the hairy-nosed and sea otter assessed as endangered (Doroff et al. 2021; Khoo et al. 2021; Roos et al. 2021; Sasaki et al. 2021; Wright et al. 2021). Asian otters face a multitude of threats such as loss of suitable habitat, habitat pollution, human-otter conflicts, depletion of prey base, and the illegal and/or unsustainable wildlife trade (Doroff et al. 2021; Khoo et al. 2021; Roos et al. 2021; Sasaki et al. 2021; Wright et al. 2021). While information on population densities throughout their range is sparse, all five species are thought to be in decline. In particular, the commercial wildlife trade has had a considerable impact on otter populations throughout the region, from significant population declines of all otter species to local extinctions of some species in parts of their range due to high levels of poaching and unsustainable harvesting (Zaw et al. 2008; Lau et al. 2010; International Otter Survival Fund (IOSF) 2014). The hunting and trade of otters predominantly supplies demand for (1) fur used in the making of coats, hats, and scarves and as embellishments on traditional garments; (2) skins for trophies; (3) parts used in traditional medicines; and (4) live animals for the pet industry which is considered the most pressing threat to the survival of some otters, particularly the small-clawed otter in Southeast Asia (Banks et al. 2006; Kruuk 2006; Duckworth and Hills 2008; IOSF 2014; Gomez et al. 2016; Duplaix and Savage 2018; Gomez and Bouhuys 2018).

Research has shown the commercial exploitation of otters in Southeast Asia is in violation of national laws and international wildlife trade conventions, i.e. the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) (IOSF 2014; Gomez et al. 2016; Gomez and Bouhuys 2018). All five species have been listed in the CITES Appendices since 1977: the Eurasian Otter in CITES Appendix I and the other four in CITES Appendix II. In response to international trade threats, the small-clawed otter and the smooth-coated otter were up-listed from CITES Appendix II to Appendix I during the 18th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CoP18) held in Geneva, Switzerland, in 2019. This boost in protection was needed for otters particularly the small-clawed otter, which more than any other otter species is highly sought after for the international pet trade. The Appendix I listing generally bans all international commercial trade in wild otters of these two species. In theory, stronger regulation might lead to greater scrutiny of the illegal otter trade by enforcement agencies and strengthening of national laws protecting these two species. A CITES Appendix I listing also means that for these species to be in international commercial trade, they must be sourced from commercial captive-breeding facilities that are certified by and registered with national CITES authorities and the CITES Secretariat, must be second-generation captive-bred, and must be accompanied by permits issued in exporting and importing countries (refer https://cites.org/sites/default/files/document/E-Res-12-10-R15.pdf).

Vietnam is a significant consumer country of illegal wildlife. This has not only resulted in the depletion and near extinction of many native species but drives the poaching and killing of wildlife on a global scale (EIA 2019; Sexton et al. 2021; USAID 2021). All Asian otter species occur in Vietnam except for the sea otter, but according to de Silva (2011), there are no current data on the status of these species in Vietnam although Duckworth and Le (1998) attributed the low sightings of otters throughout the country to either a significant drop in numbers or to more elusive behaviour by otters. Recent research into the otter trade in Southeast Asia has shown Vietnam to be a key end use destination for illegally sourced live otters for the pet trade and otter fur used in the fashion industry (Gomez and Bouhuys 2018). Seizure data analysis over the past decade provided evidence of the smuggling of otters from other parts of Asia into Vietnam (Gomez et al. 2016; Gomez and Bouhuys 2018). Coudrat (2016), in a preliminary assessment of otter populations in the Nakai-Nam Theun National Protected Area in Lao PDR, stated that while trapping pressure on otters has reduced to a certain extent due to less demand for otter skins, they are still targeted by Vietnamese hunters.

In general, the Eurasian otter, hairy-nosed otter, small-clawed otter, and smooth-coated otter are nominally protected by legislation in most range states in Southeast Asia. In Vietnam, native otter species are strictly protected under several laws governing the protection and trade of wildlife (Table 1). All four species are listed in Annex I of Decree 160/2013/ND-CP on Criteria for identification and management of endangered, rare and precious species, prioritized for protection which stipulates principles for the preservation and conditions for the exploitation, exchange, purchase, sale, transport, captive-breeding, rescue, etc. of listed species. They are also listed in Group IB of Decree 06/2019/ND-CP on Management of endangered, precious, and rare species of wild plants and animals and Enforcement of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora which prohibits the exploitation or use of native otter species for commercial purpose. Penalties for administrative violations of the country’s wildlife legislation are stipulated in Decree 35/2019/ND-CP on Administrative Penalties in the field of forestry (hereafter Decree 35), with maximum fines of VND500 million (~ USD21,360) and VND1 billion (~ USD42,719) for individuals and legal entities respectively. Criminal violations are stipulated in the Penal Code 100/2015/QH13 (hereafter Penal Code 100) and Law 12/2017/QH14 Amending and Supplementing articles in Penal Code No. 100/2015/QH13 (hereafter Law 12) and, for individuals, may lead to a maximum jail sentence of 15 years or a VND5 billion (~ USD213,597) fine. Legal entities may be fined up to VND15 billion (~ USD640,790) and could face suspensions of 6 months to 3 years. Additionally, since 1 January 2021, the commercial advertisement of wildlife is regulated under Law on Investment No.61/2020/QH14 dated 17 June 2020. Penalties under this law range between VND70 million (~ USD2990) and VND100 million (~ USD4272) for illegal exploitation of Class IB species.

Methodology

Seizure data

This study provides an update on previous otter seizure data analyses conducted in the Southeast Asian region from 1980 to 2017. Here, we focus specifically on otter seizures in Vietnam covering the period 2018 to 2021. Data were obtained from various sources including the CITES Trade Database, media reports, grey literature, and records from other non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as Education of Nature - Vietnam (ENV) and Robin des Bois. Searches for seizures were conducted in both English (search terms: hunting, trapping, confiscation, illegal trade in otter) and Vietnamese (search terms: bắt giữ rái cá, xử phạt rái cá, rái cá trái phép). All reported seizures were carefully checked to avoid duplication. Formal requests for otter seizure data were also sent to CITES Management Authorities (MA) in Vietnam. All records of seizures of live or dead otters, their parts and derivatives were then collated and analysed.

From each record obtained, we extracted, where available, information pertaining to date of seizure, species of otter seized, commodity (live animals, body parts, etc.), quantities of each commodity seized, purpose of hunting/trade (i.e. for consumption, pets, trophies, etc.), location of seizures and trafficking routes, suspects arrested, and prosecution outcomes. Using this data, we mapped trade hubs. Species identification was based on information extracted from seizure records obtained, and it is assumed to be as reported when further verification was not possible.

Due to inherent biases in the way seizure data are reported, i.e. due to varying levels of law enforcement, reporting and recording practices, language biases, etc., this dataset is interpreted with caution. It should be noted that the presented data set should not be assumed to encompass absolute trafficking volumes or scale of the otter trade in Vietnam given the inherently covert nature of the illegal wildlife trade.

Online survey

Online surveys were conducted over a 12-week period, between 1 December 2021 and 28 February 2022, focusing on Facebook groups and commercial trade portals advertising otters for sale. Advertisements posted from 1 January 2018 to 28 February 2022 were gathered. Surveys consisted of 1 h of research per week, gathering as many adverts on otters as possible. Survey platforms advertising otters for sale were identified using Google and searching for combinations of words like “otter”, “sale”, and “buy” in Vietnamese (Table 2). Through this process, Facebook, Lazada, and Shopee were the main platforms observed with advertisements for otters and otter products. Further search within these three platforms was subsequently conducted using the same survey keywords (Table 2). Only open access platforms/groups were surveyed.

Data extracted from each post/advertisement included location/base of operation of seller (if available), species of otter (accepted as stated where no pictures were provided), commodity for sale (live, fur, parts), quantity, size and age of live otters and price of item(s). Quantity of otters or products for sale was recorded based on either the caption or photos provided. Where these were not available, a minimum number of one was recorded. Posts/advertisements that did not display any intent of sale were left out of the data collection. No personal data about the sellers were collected and no interaction with sellers took place. To avoid any inflation of numbers, care was taken to review every advertisement and eliminate all duplicates, including those that appeared with different dates.

Results

Seizure data analysis

We obtained 22 records of otter seizures that occurred in Vietnam between 2018 and 2021. The highest number of incidents took place in 2020 followed by 2019 (Table 3). A total of 85 live otters and four dead otters were confiscated. In comparison to past otter seizure data analysis (refer: Gomez et al. 2016; Gomez and Bouhuys 2018), there appears to be a steady increase in the number of seizures involving otters in Vietnam over the years with a peak in 2020 (Table 3). The highest quantities of otters were seized in 2019 and 2020 (Table 3).

Small-clawed otter was the species most frequently seized with 74 animals confiscated in 16 incidents. At least nine Eurasian otters and one smooth-coated otter were seized in one incident each. In four incidents, the species of otter seized was not reported. Juvenile otters were reported as confiscated in 11 of the incidents obtained.

Seizures occurred in at least 14 provinces/cities with Ho Chi Minh City having the highest number of incidents (n = 6) followed by Hanoi (n = 3) (Fig. 1). The greatest quantity of otters was confiscated in Ho Chi Minh City (n = 22), followed by the provinces of Nghe An (n = 15) and Hai Phong (n = 14) (Fig. 1).

To date, 11 of the 22 seizure incidents have resulted in successful prosecution. Eight cases resulted in prison sentences of 1-year suspended sentence (n = 1), 1.6 years (n = 3), 6 years (n = 1), and 11 to 12 years (n = 3). Three cases resulted in fines only of VND10 million (~ USD427) (n = 2) and VND500 million (~ USD21,360) (n = 1).

Online survey findings

There were at least 130 advertisements for otters and otter fur products observed during the survey period. The majority of these were found on Facebook (89%) followed by Shopee (10%) and Lazada (1%).

At least 73 unique sellers were identified encompassing individuals (n = 45), online fashion stores (n = 26), online pet stores (n = 1), and Facebook page (n = 1). It is observed that the majority of individuals are opportunistic sellers as only three out of 45 individuals can be identified as non-opportunistic sellers. However, on Facebook, there were also regular sellers using individual accounts instead of ‘pages’. This is probably because Facebook groups can select whether or not to allow pages to post in groups. Another possible explanation is that, to promote Marketplace’s selling function, Facebook tends to limit engagement of posts by pages that are deemed for selling.

The location of sellers was only reported in five advertisements, i.e. Binh Duong (1), Da Nang (1), Ho Chi Minh (2), and Tien Giang (1), and all five advertisements were for live otters.

Of the 130 advertisements, 87 were selling otter fur products (e.g. coats, scarves, gloves, hats) amounting to 3243 items, and 43 were selling live otters amounting to 72 animals (Table 4; Fig. 2). Of these, it was not possible to ascertain the authenticity of the otter fur products or to identify the otter species. Of the 72 live otters being advertised for sale, 36 were identified to species level, all of which were the small-clawed otter (Fig. 2). None of the advertisements mentioned CITES permits.

Only 15 advertisements provided information on origin. The majority of these were from Japan (n = 11 advertisements; 1010 products) followed by China (n = 3 advertisements; 72 products) and South America (n = 1 advertisement, 1 product). There were an additional six advertisements offering 12 products that stated ‘imported from overseas’, but no specific country was provided.

Price data were obtained for 3054 otters and otter fur products. The total quoted value of these products was VND8,934,960,000 (~ USD390,000). The price for otter fur products ranged widely, i.e. from VND249,000 (~ USD11) for a coat with otter fur trimmings to VND24.5 million (~ USD1072) for a whole otter fur coat. For live otters, the price ranged from VND2.5 million to VND4.5 million (~ USD110–USD197).

Discussion

Otters face a multitude of threats, not the least of which is exploitation for commercial trade. The treatment of wild plants and animals as commercial commodities has come to be among the greatest threats to biodiversity, economic security, and human health. The high economic value of wildlife trade has meant that legal and illegal markets flourish alongside each other (Phelps et al. 2016; Wong 2019; UNODC 2020). In this study, we found that Vietnam’s trade in otters revolves primarily around the fashion and exotic pet industries. This is consistent with past studies on the otter trade in Asia (Gomez et al. 2016; Gomez and Bouhuys 2018). When comparing the data of all studies, the scale of the otter trade in Vietnam appears to be greater than previously reported (see Table 3). This could possibly be due to increased trade levels, enforcement effort or perhaps better reporting of seizure incidents. That said, online advertisements for otter products were also substantially higher than the previous study. Gomez and Bouhuys (2018) found 15 advertisements of otter fur products and six advertisements for 12 small-clawed otters in a 5-month survey. In comparison, we found 130 advertisements for live otters (72 animals) and otter fur products (3241 items) in the same time frame. Otters are protected species in Vietnam. During the survey, it was observed that many sellers and buyers are aware of the illegality of trading in live otters based on the comments and open discussions on the posts. However, it was not the case for otter fur products which were openly advertised and traded without any mention of permits in clear violation of Vietnam’s wildlife laws.

Fur trade

We found large quantities of various otter fur products for sale online including coats, gloves, hats, and scarves. Based on at least 15 advertisements, the claimed origin of some otter fur products was reportedly Japan (n = 11) and China (n = 3). Most advertisements (88.5%) however provided no information on origin. It was also never reported which species of otter the products were made from.

It is legal in some parts of the world such as Canada and the United States of America (US) to trap and trade wild otters (Nichol 2015; Yoxon 2021). It is also legal to trade otters internationally with a valid CITES permit. According to the CITES Trade Database, between 2010 and 2020, there were 599 records of international trade involving otter products (skins, garments, trophies) globally amounting to 298,207 items (importer reported quantities) and 436,577 items (exporter reported quantities). Canada and the US were the main exporters of otter fur products while China was the main importer. There were no records of otter fur imports into Vietnam during this time. There were also very few records of otter fur imports (7 records of 45 items) or exports (1 record of 2 garments) involving Japan. None of the advertisements observed during the study period mentioned CITES permits. It therefore seems likely that the trade in otter fur products occurring online in Vietnam is illegal and in violation of CITES. Our study suggests that Japan has an active trade in otter fur products. Japan’s native otter species, the Japanese Otter Lutra lutra whiteleyi, has been declared extinct since 2012 (though there have been reports of sea otter sightings in Japan, generally of single individuals except for a recent sighting of 20 — Doroff et al. 2021). It is therefore fair to assume the source of otter fur is derived from outside the country.

Despite their protection status in Asia, the poaching and killing of otters for illegal trade exists throughout the region (IOSF 2014; Gomez and Bouhuys 2018; Kitade and Naruse 2018; Siriwat and Nijman 2018). Between 1980 and 2015, there were a minimum of 161 recorded otter seizures across 15 countries in Asia, the majority of which were skins (Gomez et al. 2016). These seizures implicated China as the main destination. Vietnamese nationals have also been reported in the poaching of otters in neighbouring countries due to demand for their fur. Prior to 2019, Japan was as a major destination for smuggled otter pups for the exotic pet trade (Gomez and Bouhuys 2018; Kitade and Naruse 2018). The otter fur trade in Japan has not been previously examined but at least one otter skin belonging to the Eurasian otter and originating from South Korea was seized in Japan (Gomez et al. 2016). Kruuk (2006) also noted Japan as an important market for Eurasian otter skins. This considering, further investigation into its role in the potential illegal trade of otter fur/skin products is worth exploring.

Pet trade

The trade in exotic species as pets is on the rise in Vietnam (ENV 2021). There is a clear demand for pet otters in Vietnam which is perpetuating this illegal trade. All seizures involving otters in Vietnam were of live animals, the majority of which were small-clawed otters. Furthermore, at least 33% of online advertisements were for live otters. The online advertisements and sale of live otters is in violation of national laws. Despite this, the online market for pet otters appears to be increasing in Vietnam. In 2017, six advertisements for 12 live otters were found in a 5-month study. In 2021/2022, the number of advertisements for live otters has risen to 43 and the number of otters for sale to 72 in a similar study time frame. Of the seizure incidents found, nine were the result of further investigation into the advertising of otters for sale on Facebook (n = 8) and Tik Tok (n = 1).

The sourcing of live otters requires in-depth investigation considering the threat status of otters in Asia. While otter populations in Vietnam are unknown, they are considered rare and in decline (Duplaix and Savage 2018). In Vietnam, captive breeding is allowed for any species with a valid permit. However, because otter species are all listed in CITES Appendix I or II, the harvesting of otters from the wild is prohibited under Vietnam’s legislation. This, in theory, would prevent the harvesting of native otters (i.e. to obtain parent stock) for commercial captive-breeding purposes. As it stands, there are no legitimate commercial otter captive-breeding facilities in Vietnam. There are some rescue centres and zoos in Vietnam that do have otters, but these are not bred for commercial trade. Based on CITES Trade Data, there are only two import records of live otters into Vietnam: in 1997, two captive-bred small-clawed otters from Indonesia were exported to Vietnam for the purpose of circus/travelling exhibition, and in 2016, eight captive-bred small-clawed otters from Uzbekistan were exported to Vietnam for commercial purposes. Indonesia’s role in trafficking otters both domestically and internationally is well known (Gomez and Bouhuys 2018), and corruption facilitates the laundering of wild-caught otters as captive-bred (Parker and Slattery 2020). Much less is known about the captive-breeding and trade of otters in Uzbekistan. Vietnam’s current wildlife legislation however allows the import of protected species if accompanied by the appropriate CITES permits. Hence, otters that are reportedly captive-bred can be imported into Vietnam legally and subsequently kept as pets. Despite this, the seizure data shows that more wild caught otters are being trafficked than are being legally imported for the pet trade in Vietnam. This is supported by previous studies into the illegal otter trade in Asia (An 2015; Gomez et al. 2016; Gomez and Bouhuys 2018).

Conclusion

The trade of otter fur products and live otters in Vietnam is occurring in violation of domestic wildlife laws and the CITES convention. The export of otter fur products to Vietnam should be accompanied by CITES permits, yet there are no import/export records involving Vietnam and as such any otter fur product brought into Vietnam should therefore be deemed illegal. Similarly, as protected species, the advertising and trade of live otters in Vietnam is illegal but continues to persist on social media. The increasingly easy access online platforms provide consumers to wildlife products and wildlife traders to consumers presents a considerable threat to biodiversity in Vietnam and the region. According to the Vietnam E-Commerce Association (VECOM), the country’s e-commerce market grew at an average annual rate of 30% between 2015 and 2019 (VECOM 2021). In 2021, as the COVID-19 pandemic slowed down the world’s economy, the growth rate of e-commerce in Vietnam still recorded a high rate of more than 20%, while other sectors and industries struggled to grow or recorded deficit (VECOM 2022). Clearly the online trade of wildlife and wildlife products in Vietnam requires greater monitoring, regulation, and enforcement to prevent the advertising and trade of illicit wildlife. In-depth scrutiny of online sellers and product sourcing is particularly warranted. Policing the trade of wildlife on online platforms is acknowledged to be a significant enforcement challenge (Xu et al. 2020; Nijman 2022). To mitigate this challenge, holding social media and other online advertising companies accountable for enabling the illegal trade of wildlife therefore needs to be strongly considered (Goodman 2019; Mazúr and Patakyová 2019; Renctas 2022).

Data availability

The data is generally available upon request to Monitor Conservation Research Society.

References

An K (2015) Ho Chi Minh City pet shop owner arrested for wildlife smuggling. http://www.thanhniennews.com/society/ho-chi-minh-city-pet-shop-owner-arrested-for-wildlife-smuggling-55571.html. Accessed 3 Feb 2018

Banks D, Desai N, Gosling J, Joseph T, Majumdar O, Mole N, Rice M, Wright B, Wu V (2006) Skinning the cat: crime and politics of the big cat skin trade. London, UK and Wildlife Protection Society of India, New Delhi, India, Environmental Investigation Agency

Coudrat CNZ (2016) Preliminary camera-trap otter survey in Nakai-Nam Theun National Protected Area, Nov–Dec 2015. Final Report (PDF) (Unpublished)

de Silva PK (2011) Status of otter species in the Asian region status for 2007. Proceedings of Xth International Otter Colloquium, IUCN Otter Spec Group Bull 28A:97–107

Doroff A, Burdin A, Larson S (2021) Enhydra lutris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021:e.T7750A164576728. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T7750A164576728.en. Accessed 8 Jul 2022

Duckworth D, Le XC (1998) The smooth-coated otter Lutrogale perspicillata in Vietnam. IUCN Otter Spec Group Bull 15(1):38–44

Duckworth JW, Hills DM (2008) A specimen of Hairy-nosed otter Lutra sumatrana from far northern Myanmar. IUCN/SCC Otter Spec Group Bull 25(1):60–67

Duplaix N, Savage M (2018) The global otter conservation strategy. IUCN/SSC Otter Specialist Group, Salem, Oregon, USA

EIA (2019) Running out of time: wildlife crime justice failures in Vietnam. Environmental Investigation Agency, London, UK. https://eia-international.org/wp-content/uploads/EIA-report-Running-out-of-Time.pdf

ENV (2021) A snapshot: exotic species trade in Vietnam 2021. Education for Nature – Vietnam. https://env4wildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/A-Snapshot-of-Exotic-Species-Trade-in-Vietnam-2021-EN-November-4-2021-final.pdf. Accessed 23 Jun 2022

Gomez L, Bouhuys J (2018) Illegal otter trade in Southeast Asia. TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia

Gomez L, Leupen BTC, Theng M, Fernandez K, Savage M (2016) Illegal otter trade: an analysis of seizures in selected Asian countries (1980–2015). TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia

Goodman AEJ (2019) When you give a terrorist a twitter: holding social media companies liable for their support of terrorism. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2489&context=plr. Accessed 1 Jul 2022

International Otter Survival Fund (IOSF) (2014) The shocking facts of the illegal trade in otters. International Otter Survival Fund (IOSF), Broadford, Isle of Skye, Scotland, UK

Khoo M, Basak S, Sivasothi N, de Silva PK, Reza Lubis I (2021) Lutrogale perspicillata. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T12427A164579961. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T12427A164579961.en. Accessed 8 Jul 2022

Kitade T, Naruse Y (2018) Otter alert: a rapid assessment of illegal trade and booming demand in Japan. TRAFFIC Japan

Kruuk H (2006) Otters: ecology, behavior and conservation. Oxford University Press, New York

Lau MW, Fellowes JR, Chan BPL (2010) Carnivores (Mammalia: Carnivora) in South China: a status review with notes on the commercial trade. Mammal Rev 40(4):247–292

Mazúr J, Patakyová MT (2019) Regulatory approaches to Facebook and other social media platforms: towards platforms design accountability. Masaryk Univ J Law Technol 13(2):219–242

Nichol LM (2015) Sea otter conservation. Conserv Practice 369–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801402-8.00013-5

Nijman V (2022) Analysis of trade in endemic Javan hill partridges over the last quarter of a century period. Avian Biol Res 17581559221086469

Parker A, Slattery L (2020) Trade and trafficking in Small-clawed otters for the exotic pet market in Indonesia, Japan and Thailand. In: Lemieux, A.M. (Ed). The poaching diaries (vol. 1): crime scripting for wilderness problems. https://popcenter.asu.edu/sites/default/files/the_poaching_diaries_vol._1_crime_scripting_for_wilderness_problems_lemieux_2020.pdf

Phelps J, Biggs D, Webb EL (2016) Tools and terms for understanding illegal wildlife trade. Front Ecol Environ 14(9):479–489

Renctas (2022) Facebook fined U$2 million for facilitating the trafficking of wild animals in Brazil. https://renctas.org.br/facebook-fined-u2-million-for-facilitating-the-trafficking-of-wild-animals-in-brazil/. Accessed 8 Jul 2022

Roos A, Loy A, Savage M, Kranz A (2021) Lutra lutra. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021:e.T12419A164578163. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T12419A164578163.en. Accessed 8 Jul 2022

Sasaki H, Aadrean A, Kanchanasaka B, Reza Lubis I, Basak S (2021) Lutra sumatrana. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021:e.T12421A164579488. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T12421A164579488.en. Accessed 8 Jul 2022

Sexton R, Nguyen T, Roberts DL (2021) The use and prescription of pangolin in traditional Vietnamese medicine. Tropical Conservation Science 14:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082920985755

Siriwat P, Nijman V (2018) Using online media-sourced seizure data to assess the illegal wildlife trade in Siamese rosewood. Environ Conserv 45(4):352–360. https://doi.org/10.1017/S037689291800005X

UNODC (2020) Pangolin scales. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2020

USAID (2021) Counter Wildlife Trafficking Digest: Southeast Asia and China, 2020. Issue IV. https://www.usaidwildlifeasia.org/resources/reports/inbox/cwt-digest-2020/view. Accessed 19 Jun 2021

VECOM (2021) E-commerce development cooperation in Ho Chi Minh City. The Vietnam E-commerce Association. http://en.vecom.vn/e-commerce-development-cooperation-in-ho-chi-minh-city. Accessed 23 Jun 2022

VECOM (2022) Vietnam E-commerce Index Report 2022. https://vecom.vn/bao-cao-chi-so-thuong-mai-dien-tu-viet-nam-2022. Accessed 23 Jun 2022

Wong R (2019) The illegal wildlife trade in China: understanding the distribution networks. Palgrave Macmillan, Switzerland

Wright L, de Silva PK, Chan B, Reza Lubis I, Basak S (2021) Aonyx cinereus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T44166A164580923. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T44166A164580923.en. Accessed 8 Jul 2022

Xu Q, Cai M, Mackey TK (2020) The illegal wildlife digital market: an analysis of Chinese wildlife marketing and sale on Facebook. Environ Conserv 47:206–212. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892920000235

Yoxon B (2021) A review of trapping of North American river otters (Lontra canadensis). OTTER, Journal of the International Otter Survival Fund 2021:26–39

Zaw T, Htun S, Po SHT, Maung M, Lynam AJ, Latt KT, Duckworth JW (2008) Status and distribution of small carnivores in Myanmar. Small Carnivore Conservation 38:2–28

Acknowledgements

We thank Chris R. Shepherd, Loretta Shepherd, and Jason Palmer for their constructive comments that improved earlier versions of this manuscript. We also thank our many donors who made undertaking this project possible.

Funding

This study was supported by funding obtained through the Global Giving Platform.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lalita Gomez contributed to the study conception, design, and data analysis. Online survey and data collection was performed by Minh Nguyen. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Lalita Gomez, and Minh Nguyen commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Both authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gomez, L., Nguyen, M.D.T. A rapid assessment of the illegal otter trade in Vietnam. Eur J Wildl Res 69, 77 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-023-01707-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-023-01707-w