Abstract

Large numbers of gamebirds (pheasants Phasianus colchicus, red-legged partridges Alectoris rufa and mallard Anus platyrhynchos) are released annually in the UK to support recreational shooting. It is important to know how many of these birds are being released because their release and management has ecological effects on the wildlife and habitats of the UK. There is little regulation governing their release, and consequently, an accurate figure for the numbers being released is unknown. I took 12 different approaches, totalling 4329 estimates of the numbers of birds being released annually, based on a series of datasets that described numbers of birds being held for breeding, rearing or release, being released, managed or shot on game shoots, being shot by individual guns or being recorded during breeding bird surveys. These 12 approaches produced estimates ranging from 14.7 to 106.1 million with a mean of 43.2 million (95% CI 29.0–57.3 million). This suggests that 31.5 million pheasants (range 29.8–33.7 million), 9.1 million red-legged partridges (range 5.6–12.5 million) and 2.6 million mallard (range 0.9–6.0 million) are released annually in the UK. These figures differ substantially from both official records of gamebirds and previous published estimates, and I discuss why such differences may occur. I set these figures in the context of the number and behaviour of shoots operating in the UK. Improved estimates of numbers of gamebird being released are critical if we are to better understand the ecological effects occurring in areas where they are released and managed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

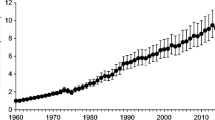

Recreational hunting (aka shooting) in lowland UK is predominantly based on the harvest of birds that have been specifically reared and released each year for the purpose (Martin 2011, 2012). Pheasant Phasianus colchicus and red-legged partridges Alectoris rufa are not native to the UK but have been introduced as quarry species on several occasions over the past centuries and have become naturalised (Lever 1977). Mallard Anas platyrhynchos are native, and their breeding and release for shooting are believed to have started in 1890 (Sellers and Greenwood 2019). It is estimated and commonly stated that tens of millions of individuals of these three species are released annually and an index of numbers being released has shown increases since the 1960s of around 900% for pheasants (Robertson et al. 2017), 590% for mallard (Aebischer 2019) and 6395% for red-legged partridges (Aebischer 2019). However, the most recent estimate of the numbers of pheasant and red-legged partridge involved is accompanied by very large margins of error (being between 38 and 49% of the mean values). For pheasants, Aebischer (2019) calculated that 47 million birds were released annually, with 95% confidence intervals spanning 39 to 57 million. For red-legged partridges, Aebischer (2019) calculated that 10 million birds were released annually, with 95% confidence intervals spanning 8.1 to 13 million. There was no estimate of the numbers of mallard released. The only published mallard release numbers date back to 1985 when around 500,000 were estimated to be released (Harradine 1985).

An accurate understanding of the number of birds being released is important. The release of large numbers of birds and their subsequent management is believed to cause a variety of positive and negative ecological impacts on the habitats and wildlife of the UK (reviewed by Madden and Sage 2020; Mason et al. 2020; Sage et al. 2020). Each year’s release introduces a large amount of biomass into the ecosystem (Blackburn and Gaston 2021). Releases usually occur in lowland UK during the late summer, with cohorts of birds being placed in woodland release pens (pheasants), farmland pens (partridges) and ponds (mallards) (The Game Conservancy Limited 1996). The direct effects, caused by the birds themselves, are typically bad for habitats and wildlife in the immediate areas where releases happen and might be expected to scale with the numbers of birds released in a rather predictable manner (Sage et al. 2005). At high densities, the released birds may exert effects including physical disturbance of soils, altering nutrient levels, changes in floral composition and changes in invertebrate community composition (reviewed in Madden and Sage 2020; Mason et al. 2020; Sage et al. 2020). The birds disperse from the release pens over the following months, and during this time, they are commonly killed or scavenged by generalist predators including foxes and raptors (Madden et al. 2018). The carcases provide a nutrient resource, and it has been suggested that they support higher numbers of predators than might naturally be expected (Roos et al. 2018). These releases are accompanied by associated effects on habitats and wildlife that are the result of human management motivated by gamebird release, including retaining, planting or managing areas of cover vegetation, the control of predators deemed a threat to the released birds and the provision of supplementary feed (reviewed in Madden and Sage 2020; Mason et al. 2020; Sage et al. 2020). Unlike direct effects, the relationship between the numbers of birds released and the occurrence or scale of associated effects is not likely to be so straightforward. In general, bird release is accompanied by larger areas of woodland being established or maintained, higher levels of predator control and large quantities of supplementary feed that is provided either via hoppers or seed-bearing crops (reviewed in Madden and Sage 2020; Mason et al. 2020; Sage et al. 2020). In order to better understand the scale of the direct and associated effects accompanying the release of birds for shooting, it is essential to have a reliable figure of the numbers of birds being released.

It would appear that the Poultry Register, administered by the Animal and Plant Health Authority (APHA), should be able to provide a definitive number of birds being released. Prompted by the growing recognition of risks to poultry and wild birds from avian influenza, a registration system was established in 2006 as a requirement of the Avian Influenza (Preventative Measures) (England) Regulations 2006. This register is obligatory for holdings with flocks of more than 50 birds, and voluntary registration of flocks that are smaller than 50 birds is encouraged. It covers the whole UK, explicitly includes birds kept for ‘restocking game birds’, and demands detailed numerical and spatial data about how many birds of what species are held where and for what purposes. It asks for separate numbers of birds of each species that are held for breeding for shooting, rearing for shooting and released for shooting.

Alternative estimates of the numbers of birds being released may be possible by conducting a series of extrapolations based on other current and historical datasets that relate to their rearing, release, management and shooting (Fig. 1). First, indications of the numbers of birds that are reared annually may be available from import figures relating to the numbers of chicks or eggs brought into the country. It may also be possible to calculate the number of eggs or chicks being produced in the UK based on the anticipated productivity of adult birds reported as being held for breeding. Second, non-regulatory, economic surveys of shoots may provide data on the numbers of birds that are being released on shoots of different types and sizes. By extrapolating these numbers while accounting for the size and type of shoots, estimates may be obtained. Third, released birds require intensive management and so by considering the numbers of gamekeepers available to manage them as well as the numbers of birds that a keeper may be able to manage, estimates may be obtained. Fourth, many shoots are commercial entities and so advertise the numbers of birds that they offer to be shot per day. Using these figures in conjunction with numbers of days when shooting occurs and incorporating measures of harvesting efficiency, estimates may be obtained. Fifth, individual hunters (known as and hereafter referred to as ‘guns’) may record the numbers of birds that they shoot, and when considered in conjunction with numbers of guns, perhaps divided into classes relating to the scale and regularity of their shooting, estimates may be obtained. Finally, released birds that survive to the following breeding season may be counted as part of national Breeding Bird Survey (Woodward et al. 2020). By incorporating mortality rates (both natural and from harvest) for released birds, it is possible to back-calculate how many birds might have had to be released in order that the observed populations might be surveyed. These approaches rely heavily on data that has been collected in an informal, often unstructured manner and so may be described as ‘messy data’ (Dobson et al. 2020). One solution to such messy data is available when several separate, alternative datasets can be used to address the same question, and therefore, our confidence in the result is increased if it is reached by multiple different analytical approaches. Consequently, I have adopted a triangulation approach in which I search for consistencies or inconsistencies across 12 methods of obtaining estimates (Dobson et al. 2020). The scale of releasing has increased markedly over the past few decades, with pheasant releases increasing on average 4.3%/year (Robertson et al. 2017; Aebischer 2019). Therefore, it is important to rely on recent data, and I have predominantly used sources collected since 2016.

Methods

Overview

I drew on a variety of datasets, mainly collected since 2016, to supply measures of numbers of birds reared, numbers of birds being released, numbers of days when shooting occurred, harvest sizes, number of people that shoot and numbers of birds observed in the wild. I then multiplied various permutations of these measures in order to generate 12 sets of estimates (comprising 4329 individual estimates), each predominantly based on different approaches to calculating numbers of released birds (see “Results” section and Appendix 1).

Datasets

-

(a)

APHA Poultry Register (APHAPR2020)

Compulsory registration is required for individuals or organisations that breed, rear or release > 50 gamebirds. Voluntary registration is available to those releasing < 50 birds (Anon 2020a). During the registration process, registees are asked to report species (pheasant, partridge (no separation of red-legged and grey) and duck (no distinction by species), livestock unit animal production usage (shooting, other), livestock unit animal purpose (breeding for shooting, rearing for shooting, release for shooting) and usual stock numbers. I engaged in a Data Sharing Agreement with the Animal and Plant Health Agency in conjunction with Natural England received the data on 10 Feb. 2021.

-

(b)

Import figures

Daniel Zeichner MP asked DEFRA how many pheasant and partridge (a) poults and (b) fertilised eggs were imported into the UK in 2019. They responded on 21 July 2020 (Prentis 2020) with details of import figures for both partridges (presumed red-legged partridge) and pheasants during 2019.

-

(c)

Data extracted from Guns on Pegs advertising website (GOPDB 2019)

Guns on Pegs (https://www.gunsonpegs.com/) is a commercial advertising site where shoots looking to let days or attract syndicate members can advertise. They can enter free-text descriptions of their shoot. Entry dates are not recorded but it has been operating for 7–8 years. Between January and March 2020, I read through descriptions of 697 lowland shoots in England that advertised shooting of pheasant, partridge (no attempt is made to distinguish red-legged from grey partridge) and ‘duck’ (not specified as mallard but often contrasted with ‘wildfowl’). I extracted data on the quarry species and the bag sizes offered at each shoot, and any information about the numbers of birds released, although only 22 shoots reported this. Shoots advertising on the Guns on Pegs website (and consequently also those that participate in the website’s surveys of shoot owners and gun clients (see below)) are likely to be a non-random sample of shoots and guns in the UK, with a bias towards larger commercial shoots.

-

(d)

Guns on Pegs Game Shooting Census (GOPGSC 2017)

Guns on Pegs conducts an annual survey of guns. The results from their 2017 survey are available https://2391de4ba78ae59a71f3-fe3f5161196526a8a7b5af72d4961ee5.ssl.cf3.rackcdn.com/1815/3011/2351/1110_0118_Guns_on_Pegs_Four_Page_Leaflet_Hayley_Clifton_Final_Web.pdf. The survey included responses from 12,143 guns and reported numbers of days shot per gun and daily bag size with separation of participants by their patterns of spend. It is not specified how respondents were selected nor how representative the sample may be.

-

(e)

Guns on Pegs Shoot Owner Census (GOPSOC 2017)

This survey, also by Guns on Pegs, was conducted at the level of the shoot rather than individual guns, and the results from their 2017 survey are available https://www.gunsonpegs.com/articles/shooting-talk/the-shooting-world-by-numbers-2018-season. The survey included responses from 652 shoots across the UK and reported numbers of days shot per season, numbers of birds released, numbers of birds shot providing measures of bag size and harvest efficiency and an estimate of the numbers of UK shoots.

-

(f)

The Savills Shoot Benchmarking Survey (SSBS 2017)

Savills and the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust conducted a shoot benchmarking survey for the 2016/2017 season, and a summary of their findings is available https://www.gwct.org.uk/media/664264/shoot-benchmarking-example-participants-benchmarking-report-fictional.pdf. The survey included responses from 155 shoots and reported the numbers of shoots, numbers of birds released, number of days shot per season and average bag sizes across three different size classes. Shoots participating in this survey include those interested in the economic performance of their shoot and so the sample may be biased towards larger, more commercial shoots.

-

(g)

The economic and environmental impact of sporting shooting/the value of shooting (PACEC 2014)

PACEC (Public and Corporate Economic Consultants) conducted surveys of shooting providers and participants in 2011/2012 with responses from 16,234 in 2011/2012 (PACEC2014), including 3843 described as providers of recreational shooting including target sports, pest control, deer stalking, wild-bird game shooting and released bird game shooting. These reported numbers of people engaged in game shooting and the total number of gun-days when game shooting occurred.

-

(h)

The National Gamebird Census (NGC 2019)

The Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust coordinate the National Gamebird Census which is a voluntary scheme that collects bag statistics from up to 900 shoots annually across the UK (Aebischer 2019). The census requests data about the numbers of game species released and shot as well as data about the size of the shoot and the numbers of days it operates annually. A summary of the 2018/2019 data was kindly supplied by the GWCT on 19 Nov. 2020. Depending on the measure of interest, data from 371 to 431 shoots was available.

Estimating numbers of shoots in the UK and the distribution of their size classes

In order to make sense of the various mean values of numbers of days shot per season, mean bag size or mean numbers of birds released which could be obtained from the surveys described above, it is necessary to know how many shoots operate in the UK. I used published records and estimates and used available data to calculate a possible range of numbers that could then be used to calculate the numbers of birds being released.

The APHAPR2020 indicates that 3597 sites report holding gamebirds for release. Of these, 3441 sites (95.7%) hold pheasants for release, 1371 sites (38.1%) hold partridges for release and 602 sites (16.7%) hold duck for release. Numbers do not add up to 100% because sites can release more than just one species. Assuming that each release site is a shoot, then a minimum number of shoots in the UK is 3597.

A report by the Farm Animal Welfare Commission (FAWC 2008) provides an estimate of ~ 7000 shoots in the UK that release pheasants (presumably including 300 that release partridges), derived from the opinions of various stakeholders with no further detail to substantiate this.

The GOPSOC2017 reports, without any supporting information, that there are between 8000 and 10,000 shoots in the UK. The PACEC (2006) report states that 91% of shoots in the UK harvest released birds. Therefore, I corrected their reported figures to include only shoots where birds were released to gives estimates of between 7280 and 9100 sites.

Shoots of any appreciable size require a gamekeeper to manage them. Therefore, by knowing the number of gamekeepers in the country, it may be possible to estimate the number of shoots. The occupation of gamekeeper was last recorded in the 1981 census when ~ 2500 were recorded (Tapper 1992). The National Gamekeepers Organisation (NGO) website reports, without any supporting information, that there are currently 3000 full-time and a similar number of part-time gamekeepers in the UK (Anon 2020b). This number includes gamekeepers on grouse moors (perhaps 500 such moors (Anon 2016)) and wild-bird shoots (where releasing does not occur) and deer managers. However, the ADAS (2005) report states that the NGO estimates that only 80–90% of gamekeepers are members. Therefore, I will use a figure of 3000 gamekeepers in each category in subsequent calculations. It is not clear from the NGO website whether the part-time gamekeepers include unpaid amateurs. The Gamekeepers and Wildlife Survey reported that of 965 gamekeepers participating, 52% were full time, 18% were part time and 30% were amateurs (Ewald and Gibbs 2019). If the part-time gamekeepers from the NGO figures include both employed part time and amateurs, then the ratios appear to be similar. The number of gamekeepers can be used to estimate the number of shoots in the country.

The PACEC (2014) report indicates that 33% of providers employ at least one full-time or part-time gamekeeper. Of these, 75.7% employ one gamekeeper, 21.2% employ two and 15.2% employ three or more. Therefore, assuming that those employing three or more employ exactly three gamekeepers, of the keepers employed full time or part time, 51.0% are employed on shoots with one employee, 28.6% on shoots with 2 employees and 20.4% on shoots with 3 + employees. Sharing the 6000 gamekeepers reported by the NGO survey between shoots in this way would reveal that there are 4266 shoots that employ at least one FT or PT gamekeeper. It is interesting to note that the distribution of these employment patterns closely matches the distribution of shoot sizes derived from separate datasets (see below). Of shoots, 71.7% employed one gamekeeper and 71.2% were classed as small shoots; 20.1% of shoots employed two gamekeepers and 18.3% were classed as medium; 9.6% of shoots employed three or more gamekeepers and 10.4% were classed as large.

As described above, it is not clear whether the NGO data included unpaid, amateur gamekeepers. Ewald and Gibbs (2019) report that 30% of gamekeepers that they surveyed were amateurs and so would have been excluded from the PACEC (2014) data. If we assume that they were excluded from the NGO data, then there may be a further 2571 amateur keepers in the UK. If each is in charge of a separate shoot, then total number of shoots in the UK would be 6837.

These different approaches provide widely differing estimates of the number of shoots in the UK. These range from an absolute minimum of 3597, based on APHAPR2020 records, through a calculation based on numbers of gamekeepers of 4266 and 6837, through unsubstantiated estimates by experts of 7000 (FAWC 2008) and 7280 to 9100 (GOPSOC 2017).

Shoots are not homogeneous in their size, structure or behaviours. The SSBS2017 divides shoots into three classes based on the mean number of birds released, the average acreage shot, days shot per season and mean bag size, all of which covary, with shoots that releasing more birds also occupying larger areas of land, shooting more days per season and shooting larger bags per (let) day. I used these classifications to determine the proportion of shoots in each size class from four datasets where releases were reported. Using data from APHAPR2020, of the 3597 locations reporting that they held any gamebirds for releasing, 2685 (74.6%) reported holding < 3000 birds and thus were classed as small shoots, 600 (16.7%) reported holding 3000–10,000 and thus were classed as medium shoots and 313 (8.7%) reported holding > 10,000 and thus were classed as large shoots. Using data from the NGC2019 based on the same definitions used in SSBS2017, of the 431 shoots participating in that scheme, 243 (56.4%) reported releasing < 3000 birds and thus were classed as small shoots, 111 (25.8%) reported releasing 3000–10,000 and thus were classed as medium shoots and 77 (17.9%) reported releasing > 10,000 and thus were classed as large shoots. The SSBS2017 itself reports that of the 155 shoots that participated, 52 (33.5%) were classed as small shoots, 54 (34.8%) were medium shoots and 49 (31.6%) were large shoots. Using data from the GOPDB2019 based on the same definitions used in SSBS2017, of the 22 shoots advertising release sizes, 15 (68.2%) reported releasing < 3000 birds and thus were classed as small shoots, 6 (27.3%) reported releasing 3000–10,000 and thus were classed as medium shoots and 1 (4.5%) reported releasing > 10,000 and thus was classed as a large shoot. The distributions of shoot classes did not differ across these in these four datasets (Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests between pairs of datasets, all K > 0.6, P > 0.1). Therefore, I calculated a weighted average (accounting for the number of shoots included/survey) across these four datasets meaning that 71.2% of shoots are small, 18.3% are medium and 10.4% are large.

A strong skew in release sizes is also indicated by the GOPGSC2018 which reports that of the 652 shoots included, 7% of them (46 shoots) accounted for releasing half of the 2,058,117 birds (a mean of 22,371 birds released/ ‘large’ shoot), and therefore, the remaining 606 smaller shoots have a mean release of 1698 birds.

The PACEC (2014) survey calculated that there are 23,000 providers of driven game shooting and 21,000 providers of walked up game shooting. It is not clear what the overlap between these two categories is. Potentially, all providers offering driven shooting also offer walked up shooting. Alternatively, the two sets of providers could have been entirely separate. It is also not clear that each provider represents a physical shoot that releases birds. Some providers may not release birds but instead shoot wild birds (including grouse) or shoot released birds that immigrate from neighbouring release sites. The class ‘providers’ include both the organisations that offer shooting (estates and syndicates) and individuals occupying key roles within those organisations (e.g. manager, secretary, treasurer, shoot captain, gamekeeper, farmer, estate manager, landowner, leaseholder). The survey attempted to correct for the risk of multiple providers representing single shoots, but there was no explicit link to individual shoot identity. The earlier PACE (2006) survey reports that 91% of respondent to that survey released gamebirds, so we might reduce the number of providers by that amount implying that the number of shoots ranges from 20,930 (if all providers of driven shoots simultaneously offer walked up shooting) to 40,040 (if providers exclusively offer driven or walked up shooting). I attempted to determine how well shoots, contributing to other surveys, correspond to these providers. I did this by using the class distributions and acreages reported in SSBS2017 and NGC2019 datasets to determine what area of the UK would be occupied if providers were synonymous with shoots. If we assume that gamebird release is concentrated in the lowlands and that of the 244,000 km2 of the UK (World Bank 2020), 40% of UK is uplands (RSPB 2007), then there might be around 146,400 km2 of land suitable to host released bird shoots. With 20,930 providers assigned to shoot classes in the same distributions as reported in other datasets and occupying the same mean area as reported in those datasets, they would be expected to occupy 184,810–291,822 km2. With 40,040 providers, 353,549–558,269 km2 would be required to host them (at least 1.4 times greater than the total land area of the UK). Therefore, either the estimates of providers by PACEC (2014) are inflated or more likely, they do not correspond well to other definitions of shoots on which the other datasets are based or the distributions of shoot classes in those datasets. This makes calculations treating PACEC (2014) provider data as synonymous with shoot data from other sources problematic. Therefore, I only consider provider data as a proxy for number of shoots when I have other data that is drawn from the PACEC (2014) provider survey to contribute to those calculations, specifically estimates based on mean harvests per shoot.

Results

I took 12 different approaches to calculate estimations (Fig. 2).

The 12 estimation methods of the total numbers of gamebirds released in the UK. Small black dots represent individual estimates within each method. Large red dots indicate mean values for each method. Violin plots about the means depict the distribution of the estimates. The dashed line indicates the mean value derived from the 12 estimation methods

Published data estimating numbers of released birds

Aebischer (2019) calculated that a mean of 47 million pheasants and 10 million partridges were released in 2016. Estimates of mallard release were not made. A total of 0.94 million mallard were reported shot. If all of these were released birds and that these represent one-third of the mallard that were released (matching similar ratios for pheasant and partridges), then I estimate that 2.8 million mallard were released, giving a total of 59.8 million birds being released annually. If all the mallard shot were wild born, then 57 million birds were released.

Poultry register data reporting numbers of birds held for rearing

APHAPR2020 Records for 2019 show that 11,515,950 pheasants, 4,681,749 partridges and 201,308 duck (species unspecified) were reported as reared for shooting. This produces a total of 16.4 million birds (of all species) that were reared. If these are subject to the mortality rates reported by Đorđevic et al. (2018), then between 14.8 million and 15.9 million gamebirds might be released annually.

Poultry register data reporting numbers of birds held for release

APHAPR2020 Records for 2019 show that 10,448,166 pheasants and 3,807,263 partridges and 439,827 duck (species unspecified) were reported as held for release for shooting. This produces a total of 14.7 million birds (of all species) released annually.

Estimates based on numbers bred and reared for release

In addition to birds bred in the UK, gamebird eggs and chicks are commonly produced outside the UK where more clement conditions stimulate higher and earlier productivity. Therefore, to estimate the numbers of birds that may be being bred for release, it is necessary to consider numbers of eggs and chicks from UK and EU origins and account for various stages of productivity and mortality according to the species of interest. For pheasants (1,023,036 registered as held for breeding in APHAPR2020, the ratio of males to females maintained by breeders varies from one male to between seven and 10 females is reported (Butler and Davis 2014; Kontecka et al. 2014), so we might presume that 88–91% of the birds registered for breeding are females. Đorđevic et al. (2018) summarise data reporting pheasant productivity from various studies across Europe and state that females lay 40–45 eggs, of which 85–95% are classed as fertile and of these 55–70% hatch, with 3–10% of chicks dying before the age of release. For mallard (43,677 registered as held for breeding in APHAPR2020, the breeding ratio is similar to that of pheasants (Kontecka et al. 2014). Cheng et al. (1980) report that mallard reared in the USA closed-flock game farms produced mean clutches of 41 eggs with a fertility of 99.5% and a hatchability of 71%. I could find no data on survival post-hatching to release age, so use those reported for pheasants (Đorđevic et al. 2018). For red-legged partridge (313,945 registered as held for breeding in APHAPR2020, their naturally monogamous breeding system is replicated by breeders with partridges kept in pairs. Using clutch sizes and hatchability, values (accounting for fertilisation) derived from breeding pairs on a commercial game farm in Spain of 39.5 eggs/female and 58.6% respectively (Prieto et al. 2018) based on a mix of free choice and imposed pair breeders. Again, I could find no data on survival post-hatching to release age, so use those reported for pheasants (Đorđevic et al. 2018).

In addition to birds bred in the UK, records for 2019 show that 28,248,773 pheasant eggs were imported into the UK from Europe (Prentis 2020). I calculated the number of birds that might be released from these eggs by using the range of fertility, hatchability and survival figures for pheasants described above. Furthermore, 3,299,780 live pheasants and 1,673,165 live partridges were imported (Prentis 2020). I calculated the number of these birds that might survive rearing to be released by using the survival figures described above. I made 4096 calculations (Appendix 1) of how many birds might be bred and released based on all possible combinations of the extremes of the range of sex ratios, egg productivity, fertility, hatchability and survival values described above for each species and origin source (UK bred, EU eggs, EU chicks). This gave a mean estimate of 44.3 million birds (range 35.7–54.4 million) that could be released annually.

Estimates based on mean numbers of birds reported released on an average shoot

The GOPSOC (2017) reports a mean of 4307 birds being released on each of the 652 shoots that completed their survey. The GOPDB2019 reports a mean of 4666 birds being released across the 22 shoots reporting release sizes. The APHAPR2020 reports a mean of 4085 birds being held for release across the 3597 locations. The NGC2019 reports a mean of 6142 birds being released across the 431 shoots reporting release data. I multiplied these 4 figures by the six possible numbers of shoots in the UK described above to generate 24 estimates with a mean of 30.5 million (range = 14.7–55.9 million) birds released annually.

Estimates based on reported releases accounting for variations in the scale of different shoots

As described above, the size distribution of UK shoots is skewed with a large number of small shoots releasing relatively few birds and shooting relatively small bags on relatively few days, and a smaller number of large shoots releasing and shooting many birds. Therefore, I incorporated an assumption about the distribution of shoots in my estimations. According to the SSBS2017, small shoots reported a mean release of 1532 birds of all species, medium shoots reported a mean release of 6212 birds and large shoots reported a mean release of 26,241 birds. I multiplied each of the six estimates of shoot numbers in the UK by the mean proportions of shoots in each class (calculated above) and multiplied these values by the mean numbers of birds per class. This produced 6 estimates with a mean of 31.5 million (range = 17.8–45.1 million) birds released annually.

Estimates of birds released on shoots given the available keepers to manage them

The SSBS2017 reports that the mean number of birds released per full-time keeper is 10,204. Assuming a decline in numbers that can be managed with a decline in job intensity, then each full-time gamekeeper can and does manage 10,204 released birds, each part-time keeper can and does manage 5102 released birds, and each amateur keeper can and does manage 2551 birds. I calculate from the NGO figures that if the 6000 gamekeepers included amateurs at the ratios reported by Ewald and Gibbs (2019), then with 3000 FT, 1125 PT and 1875 amateur gamekeepers, a total of 41.1 million birds could be released and managed. If the NGO figures excluded amateur gamekeepers, the 3000 part-time keepers can all manage 5102 birds each, and an additional 2571 amateur keepers are included, then 52.5 million birds could be released and managed. A mean of these two estimates is 46.8 million birds that could be released and managed annually.

Estimates based on mean harvests reported from shoots

Harvest levels depend on the number of birds shot per day, the numbers of days shot per season and the harvest efficiency of the guns. I obtained four estimates across all shoots for daily bag size. These ranged from 98/day (GOPSOC 2017), through 112/day (GOPGSC 2017), 114.5/day (NGC 2019) to 165/day (GOPDB 2019). For shoot days per season, the GOPSOC2017 reported a mean of 13 days shooting/shoot while the mean NGC2019 data reports 13.7 days shooting/shoot. I could also use the PACEC (2014) provider data in these estimates. The 40,040 providers of driven and walked up shooting report a mean of 5 days shooting/provider, and by dividing the 18.4 million pheasant, partridge and duck shot between the 220,000 shooting days, the estimated bag size was 83.6/day. The harvest or bag size represents only a fraction of the birds that will have been released. The GOPSOC2017) reports 40%, SSBS2017 reports 38% and (for pheasants) Robertson et al. (2017) reports 33% return rates. I multiplied the various combinations of harvest levels, number of shoot days, harvest efficiencies and number of shoots in the UK to generate 147 estimates with a mean of 28.4 million (range = 11.5–61.7 million) birds being released annually.

Estimates based on reported harvests accounting for variations in the scale of different shoots

As described above, shoots in the UK differ greatly in scale, so I incorporated an assumption about the distribution of shoots in my estimations in which larger shoots offer more days and harvest larger bags. The SSBS2017 described small shoots as offering 9 days/season with a bag of 80 birds, medium shoots offering 16 days/season with a bag of 148 birds and large shoots offering 41 days/season with a bag of 232 birds. The NGC2019 described small shoots as offering 7.8 days/season with a bag of 63 birds, medium shoots offering 15.3 days/season with a bag of 153 birds and large shoots offering 30.3 days/season with a bag of 223.5 birds. By using the mean distribution of shoot classes calculated above (71.2% small, 18.3% medium, 10.4% large) and considering the range of numbers of shoots in the UK and the range of harvest efficiencies as above, I generated 36 estimates with a mean of 29.4 million (range = 13.3–52.8 million birds) being released annually.

Estimates based on harvests by individuals based on the total number of guns in the UK

According to PACEC (2014), 280,000 guns shoot driven game with 150,000 shooting walked up game. These two categories are not exclusive, but there is a maximum of 380,000 people shooting live quarry (including deer, wildfowl and avian and mammalian pests), so I considered the two extreme values of 280,000 and 380,000 people shooting. The numbers of birds shot per gun varies, and this variation is captured by the GOPGSC2017. The survey identified three classes of gun from 6510 individuals (of the 12,143 surveyed) who reported spend data. Like the shoots themselves, the number of birds shot per day typically increased with the number of days shot per year. Those described as ‘low spend’ comprised 2031 guns (17%) and shot a mean of 8 days/year with a mean bag size of 73 birds/shoot. Those described as ‘medium spend’ comprised 3759 guns (31%) and shot a mean of 12 days/year with a mean bag size of 123 birds/shoot. Those described as ‘high spend’ comprised 730 guns (6%) and shot a mean of 21 days/year with a mean bag size of 212 birds/shoot. A further 5623 guns (46%) did not report their annual spend, but they shot a mean of 9 days/year with a mean bag size of 99 birds. PACEC (2014) reports a mean of 10.4 guns/day across both walked up (7 guns) and driven (3 guns) days. I assume that a day’s bag was split equally between the 10.4 guns in attendance, meaning that over one shooting season, a mean low spend gun shot 56.2 birds, a medium spend gun shot 141.9 birds, a high spend gun shot 428.1 birds, and a no spend gun shot 85.7 birds. I assumed that the distribution of people reported as shooting birds in the PACEC survey matched the distribution of the behaviours of those in the GOPGSC2017. I multiplied all combinations of numbers of guns and harvest efficiencies by the distribution of gun classes and their harvest rates to generate 6 estimates with a mean value of 106.1 million (range = 83.1–135.3 million) birds being released annually.

Estimates based on harvests by individuals based on the number of shooting days

An alternative approach to relying on estimates of the total number of people shooting live quarry is to calculate the number of days that people shoot per season. Because the four different classes of guns described above shot different numbers of days/season as well as shooting different numbers of birds on each day, I calculated the percentage of the total number of shooting days that were taken by people of the four classes (low = 13%, medium = 35%, high = 12%, no spend data = 40%) and calculated the mean number of birds that the gun was likely to shoot on that day (low = 7.0, medium = 11.8, high = 20.4, no spend data = 9.5). The PACEC (2014) reports 1.6 million gun days/season targeting driven lowland game and a further 680,000 days/season targeting walked up lowland game which may include released birds. This gives a total of 2.28 million gun days/season with a conservative estimate of 1.6 million days if all driven days also include shooting at walked up birds. Therefore, I calculated estimates of harvests based on these reported gun days being shared among the gun classes as described above and accounting for harvest efficiency. This approach produced 6 estimates with a mean of 59.7 million (range = 45.1–77.9 million) birds being released annually.

Estimates assuming that BTO breeding bird survey data is a remnant of the release population

An alternative to calculating release numbers from birds being shot is to extrapolate backwards from the numbers of birds recorded as surviving following the shooting season and before the next year’s cohort has been released. Female pheasants (2.3 million) were calculated to be present in GB during the 2016 breeding season (Woodward et al. 2020). Assuming that each hen has a single partner (generous, because pheasants are a polygynous breeding species with single males holding harems of several females, although other males may be classed as non-reproductive satellites), there are 4.6 million pheasants present in the breeding season. If these are the all the remnant survivors of the released birds and 9% of released birds survive to the start of following breeding season (Hoodless et al. 1999), I estimate a release of 51.1 million pheasants. Seventy-two thousand and five hundred red-legged partridge territories were calculated to be present in GB during 2016 breeding season (Woodward et al. 2020). Assuming that each territory comprises a single male and female, and that survival of released partridges matches that of released pheasants to the same period (9%), I estimate a release of at least 1.6 million partridges. Wintering mallard in the UK include migrants so it is not possible to reliably attempt to calculate the size of mallard releases based on breeding populations. It was estimated that there were 665,000 mallard individuals present during winter 2012/2013–2016/2017 (Woodward et al. 2020), but these could include both wild and released birds. By combining values for pheasants and partridges (but excluding mallards due to unreliable data), I estimate that 52.7 million birds could be released annually.

What is the species composition of the released birds?

Four datasets report relative numbers of the three species of released gamebirds (Table 1). These mean values of released birds are similar to percentages reported as shot in PACEC (2014): pheasants 71%, partridges 24% and duck 5%.

Summary results

Depending on the approach taken, I derived 4329 estimates of total numbers of birds being released annually with a mean of 43.6 million and range between 11.5 and 135.3 million. These estimates were derived by one of 12 different methods. The distribution of estimates across methods was unbalanced with 8 methods being based on < 10 estimates and one method based on 4096 estimates. When I weighted all 12 estimate methods equally, I obtained a mean of 43.2 million (95% CI 29.0–57.3 million, range = 14.7–106.1 million) birds released annually. These estimate methods fall into four rough groupings which approximately double in their mean value. The two estimation methods that depend on APHAPR2020 data on numbers of birds held for rearing or for release give mean values of ~ 15 million birds being released. The four estimation methods that depend on data reported by shoots about the numbers of birds that they release and harvest give mean values of ~ 30 million birds. A broad set of four different estimation methods including those based on BTO bird surveys, assumptions about gamekeeper numbers, breeding calculations from UK and EU sources and the estimated number of days that individual guns shoot produced estimates of ~ 45–60 million birds and the previous calculation by Aebischer (2019) falls within this range. Finally, the estimation method dependent on the number of guns involved in game shooting in the UK produced a notably higher mean estimate of 106 million birds.

By sharing the mean estimate for total gamebirds being released of 43.2 million birds between the mean and extreme proportions of each species reported in the datasets in Table 1, it is probable that 31.5 million pheasants (range 29.8–33.7 million), 9.1 million red-legged partridges (range 5.6–12.5 million) and 2.6 million mallard (range 0.9–6.0 million) are released annually in the UK.

Discussion

The estimates of numbers of gamebirds being released for shooting in the UK that I derived were markedly different from either of the two currently available published estimates. The mean value derived from the 12 different estimation methods of around 43 million birds is 75% of the previous estimate by Aebischer (2019) for release in 2016. Both Aebischer (2019) and Robertson et al. (2017) have reported that release numbers have been increasing annually, with Robertson et al. concluding that release densities for pheasants have been rising by 4.3%/year. If these increases apply to number of gamebirds more generally, then the 57–59.8 million released birds calculated by Aebischer (2019) from 2016 might be expected in 2020 to stand at 67.5–70.8 million. Most datasets used in my study were collected in the past 5 years, so comparisons with these higher figures are also justifiable, in which case they are around 61–64% of the previous estimation method. My mean value is also almost three times that of the numbers of birds reported as being held for release or rearing in the APHA Poultry Register for 2020. Although 2020 was an unusual year due to the COVID19 pandemic, the total reported (14.7 million birds held for release) is slightly higher than that reported in 2019 (14.3 million) suggesting that the discrepancy cannot be explained by pandemic-induced changes in reporting.

Because data reporting numbers of birds shot or their release and management did not commonly separate by species, it is difficult to be confident in the exact numbers of each species that are released. Pheasants are clearly the most commonly released birds, comprising ~ 70% of the release population. They are also released at the most sites (96%). In contrast, the numbers of partridge and mallard being released is less well known. This may be because some shoots specialise in (one of) these two species and so a small number of shoots that release large numbers of these species, indicated by the skewed APHAPR2020, NGC2019 and GOPDB2019 data, which may mean that numbers of these species are especially sensitive to records from a small number of sites. Generally, the release patterns and broader ecology of partridge and mallard is less well understood compared to pheasants (Madden and Sage 2020), and a better understanding of these species is desirable in future work.

My estimates were based on messy data (Dobson et al. 2020) for which collection did not conform to a formal study design and are thus potentially subject to unmeasured bias. This messiness is reflected by the mean estimate being highly susceptible to the methods used to derive it. However, the numerous separate datasets and estimation approaches provide alternative methods to address the same question and thus offer the opportunity to triangulate on the result (Dobson et al. 2020). The four methods that rely on shoots themselves reporting the numbers of birds that they release and shoot, either as part of their advertising or when participating in industry surveys, all produce mean estimates of around 30 million birds being released (range 11.5–61.7 million). This comparatively low estimate is surprising because there is little incentive to under-report releases or bag sizes when advertising because guns looking to purchase shooting generally want to be assured that birds will be available, and indeed perhaps prolific, to shoot. There is also little incentive to under-report these figures when responding to industry surveys, especially when they are conducted by land agencies who determine the value of land according to the scale of shooting that can be conducted there. This is in contrast with the two methods that rely on the harvest reports of the guns, which produced the highest estimates of 59.7 and 106.1 million birds (range 45.2–135.3 million) with both methods producing estimates whose ranges do not contain the mean value derived from all 12 estimates. These high estimates may result from the GOPSOC2017 focussing on a sample of guns who shoot a lot and not accounting for many guns who shoot much less regularly and on smaller days, such that the distribution of gun classes that I used does not match the distribution of guns that make up the 280,000–380,000 individuals reported in PACEC (2014). The two estimates that fell closest to the mean estimate were based on entirely separate datasets and made no assumptions about either the number of shoots in the UK or the behaviour of guns. Estimates based on gamekeeper efforts and breeding calculations both produced mean estimates of around 45 million birds. They suggest that regardless of uncertainty over how many shoots there are in the UK or how many birds guns shoot, there is the capacity to produce, release and care for about 45 million birds annually in the UK. For any estimates higher than these, it is necessary to explain where these additional birds are coming from and who is caring for them post-release. There is currently very little structured data collection on the behaviour of shoots and guns in the UK, perhaps because as a demographic, people who are involved in shooting operate as a closed shop with membership, rules, traditions and language that make it hard for academic researchers to engage (Hillyard 2007). In the absence of this and paucity of other representative data related to game release and management, it is necessary to rely on messy data. Triangulations based on estimations that independently draw on data about on the numbers of birds being produced, released, managed, shot and the survivors being counted provides a novel approach to population estimates for game species and can strengthen our confidence in their accuracy.

There are several obvious sources of variation in the datasets that I used which may contribute to noise in the resulting estimates. Variation in four of the estimate methods may be due to the uncertainty over the numbers of shoots operating in the UK. With numbers ranging from 3597 to 9100 shoots, this introduces an almost threefold variation in many estimates. If we include the providers from PACEC (2014), then the variation increases to 6- to 11-fold. It is not simply the number of shoots that is likely to be critical, but also their size and activities. The distribution of releases across shoots appears to be very skewed. Both the APHAPR2020 data and the GOPDB2019 data reveal that there are many small shoots that operate over a relatively small area, shoot relatively few birds either on each shoot day or across the season as a whole because they only shoot on a few days, and consequently release few birds. There are also a small number of very large shoots that shoot large bags on many days, typically over much larger areas of land, and consequently release many birds. From the SSBS2017 classification of shoot sizes and based on APHAPR2020 release data, 313 large shoots make up only < 9% of UK shoots, yet they appear to release 64% of the birds. In the GOPSOC 2017, it is reported of the distribution of their data that “just over 7% of shoots accounted for half of the total number of birds put down and shot”. Therefore, my estimates may not be especially sensitive to the total number of shoots in the country, but rather to the number of these especially large shoots. Given that such shoots are more likely to be commercial, they are also more likely to have advertised on Guns on Pegs website and hence have been included in the three datasets based on that website that I considered.

A second notable source of potential imprecision is the sparsity of human data covering the behaviour of those people rearing, releasing, managing and shooting the birds. The behaviour of guns and game managers is not homogenous and mirrors the skew seen in the scale of shoots described above, with the three groups of guns identified in the GOPGSC2017 varying more than sevenfold in the numbers of birds that they shot each season, ranging from 56 to 428. Despite these values being derived from a large sample of > 6000 people who declared their annual spend, the fact that it drew on people who had joined a website in order to purchase shooting suggests that they may be those individuals that shot more birds than most guns in a year. To refine these numbers, we require a deliberate sampling method that equally captures the behaviour of the occasional gun who is invited to walk around a friend’s farm twice a year, as well as that of the person for whom shooting is their main recreational hobby, shooting large numbers of birds on many days of the year at multiple sites and a methodology that can provide a reliable count of the numbers of such individuals. The PACEC (2014) report did indeed attempt to collect such large and representative samples of gun and game manager behaviour, including survey results from > 16,000 participants. Yet the authors of the 2014 report state that even this sample was likely to under-represent those with low levels of involvement or over-represent larger providers of driven game shooting. Furthermore, the report was framed as investigating economic, environmental and social benefits of shooting sports, and as such, respondents may have been moved to over-report their activities in order to support an idea that their actions had these benefits. Such over-reporting, specifically in the numbers of people involved in shooting and of days that they shot each year, may explain why my estimates based on gun days and numbers of guns produce some of the highest estimates. Consequently, one explanation for the discrepancy between my own estimates and those of Aebischer (2019) is that his analyses drew on data from the PACEC surveys reporting the numbers of birds (and other quarry) shot. If those data, like those regarding the shooting behaviour of respondents, were also imprecise and over-reported, then they may lead to especially high estimates of numbers of birds being released.

A third indicator of likely imprecision in these measures is clear contradictions or anomalies when comparing data sources. For example, the data on egg imports (Prentis 2020) records ~ 28 million pheasant eggs and no partridge eggs being imported, whereas Canning (2005) states that around 90% of red-legged partridges are hatched from imported eggs. One explanation is that some of the eggs described as being from pheasants are actually partridge eggs. A second example is that the APHAPR2020 records 16,408,007 birds being reared for released but 14,695,256 actually being held for release, a drop of 12% which is at the top end of the reported mortality rates at this stage of 3–10% (Đorđevic et al. 2018). The fate of these missing birds is unknown. The APHAPR2020 also reports that 201,308 duck were held for rearing whereas more than twice as many (439,827) were held for releasing. It is unclear where these additional birds came from. These anomalies are all seen in official DEFRA records (of imports, poultry registration or background reports) which might usually be assumed to be the more reliable data sources. Consequently, although it may be desirable to base estimates of releases on the most credible data sources, it is unclear which these may be.

Given such messy data, is there any value in trying to make estimates? I would argue that even if my mean or range of estimates are inaccurate, they highlight four aspects of our current understanding about the release of gamebirds in the UK that have important implications for future work concerning the ecological effects of gamebird release and management. First, even my most conservative mean estimate is more than twice that of the APHA figures which suggests that many game managers, perhaps most, are failing to comply with the register regulations. This is problematic, from an ecological research perspective, because it means that our data on not just the numbers of birds being released, but perhaps more importantly, their release locations, is inaccurate. Whilst it may be possible to extrapolate numbers of birds, it may be much harder to interpolate missing release locations meaning that large-scale analyses of bio-spatial patterns are difficult. If the poultry register is to form the basis of our knowledge of gamebird release numbers and locations then, if my estimations are correct, there needs to be a marked improvement in compliance. Second, my results starkly illustrate the skew in both the distributions of gamebird release sizes and the behaviour of those shooting them. Crudely, a small proportion of sites release a large proportion of the birds in the UK, and a small proportion of people who shoot them are responsible for shooting a lot of them. Most shoots release, and most guns shoot, comparatively few birds each year. The direct effects of released birds may scale with release numbers (although the strongest evidence currently suggests that their release density is a critical determinant of their effects (Madden and Sage 2020)). Additionally, the associated management effects may scale with release with larger shoots managing larger areas more intensively (e.g. larger areas of game crop planting, more thorough predator control, greater supplementary feeding). Therefore, this small number of large shoots may be responsible for disproportionate ecological effects, both positive and negative. Consequently, if we are trying to understand the net ecological effects then it is critical to ensure that sites being sampled encompass the full range of release and management scales. Third, the variation in my estimates clearly demonstrates that we have a poor understanding of even the most fundamental aspects of the ecology of gamebird release in the UK. Sutherland et al. (2006) highlighted the ecological effects of released gamebirds on biodiversity as one of the 100 questions of high policy relevance. In the 15 years since, little progress has been made in addressing this question and this may partly be because reliable data on the size and location of releases is lacking. Finally, my estimates are lower than that of Aebischer (2019), perhaps markedly so, and this has implications for how gamebird release and management is perceived both inside and outside the shooting. Currently, the figure of 57 million gamebirds being released annually (excluding mallard) is one that is quoted by both advocates and opponents of gamebird release. For both ‘sides’, there is an incentive to report high figures: for opponents, such as the League Against Cruel Sports (LACS 2020), a large number of birds can be presented as both an increased source of direct negative environmental effects (Blackburn and Gaston 2021) and a large pool of individuals that might be considered to suffer from poor husbandry or death; for advocates, high numbers can support high figures of employment (including that directed at habitat conservation) and economic benefits derived from game shooting. If my mean estimates are correct, being around 75% of the previously published figure, then it suggests that neither the scale of negative ethical or ecological effects of release, nor the positive economic benefits are as high as are currently assumed.

Availability of data and material

All data are provided in the text or in accompanying references.

References

Anon (2016) Grouse shooting. https://www.animalaid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Grouse.pdf. accessed 14 May 2021

Anon (2020a) Poultry (including game birds): registration rules and forms. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/poultry-including-game-birds-registration-rules-and-forms. accessed 14 May 2021

Anon (2020b) About gamekeeping. https://www.nationalgamekeepers.org.uk/about-gamekeeping. accessed 14 May 2021

Aebischer NJ (2019) Fifty-year trends in hunting bags of birds and mammals and calibrated estimation of national bag size using GWCT’s National Gamebag Census. Eur J Wildl Res 65:64–77

Blackburn TM, Gaston KJ (2021) Contribution of non-native galliforms to annual variation in biomass of British birds. Biol Invasions 23:1549–1562

Butler DA, Davis C (2014) The effects of plastic spectacles on the condition and behaviour of pheasants. Vet Rec 174:198–198

Canning P (2005) The UK game bird industry—a short study. Ed Adas, Lincoln, England

Cheng KM, Shoffner RN, Phillips RE, Lee FB (1980) Reproductive performance in wild and game farm mallards. Poult Sci 59:1970–1976

Dobson ADM, Milner-Gulland EJ, Aebischer NJ, Beale CM, Brozovic R, Coals P, Critchlow R, Dancer A, Greve M, Hinsley A, Ibbett H, Johnston A, Kuiper T, Le Comber S, Mahood SP, Moore JF, Nilsen EB, Pocock MJO, Quinn A, Travers H, Wilfred P, Wright J, Keane A (2020) Making messy data work for conservation. One Earth 2 (5):455-465

Đorđević N, Popović Z, Beuković D, Beuković M (2018) Production losses and mortality in voliers, nutrition and hunting conditions. Int Symp Anim Sci 83–89, Belgrade-Zeman, Serbia

Ewald J, Gibbs S (2019) Gamekeepers: conservation and wildlife. https://www.gwct.org.uk/media/1095291/NGOGWCT-Survey2019-final.pdf. accessed 14 May 2021

FAWC (2008) Opinion on the welfare of farmed gamebirds. Farm and Animal Welfare Committee, London. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/325047/FAWC_opinion_on_the_welfare_of_farmed_gamebirds.pdf. accessed 14 May 2021

Harradine J (1985) Duck shooting in the United Kingdom. Wildfowl 36:81–94

Hillyard S (2007) The sociology of rural life. Berg, Oxford

Hoodless AN, Draycott RAH, Ludiman,MN, Robertson PA (1999) Effects of supplementary feeding on territoriality, breeding success and survival of pheasants. J Appl Ecol 36(1), 147–156

Kontecka H, Nowaczewski S, Krystianiak S, Szychowiak M, Kups K (2014) Effect of housing system on reproductive results in ring-necked pheasants (Phasianus colchicus L.). Czeh J Anim Sci 59:319–326

LACS (2020) Pheasant and partridge shooting. https://www.league.org.uk/pheasant-and-partridge-shooting. accessed 14 May 2021

Lever C (1977) The naturalized animals of the British Isles. Hutchinson, London

Madden JR, Hall A, Whiteside MA (2018) Why do many pheasants released in the UK die, and how can we best reduce their natural mortality? Eur J Wildl Res 64:40–48

Madden JR, Sage RB (2020) Ecological consequences of gamebird releasing and management on lowland shoots in england: a review by rapid evidence assessment for Natural England and the British Association of Shooting and Conservation. Natural England Evidence Review NEER016. Peterborough, UK

Martin J (2011) The transformation of lowland game shooting in England and Wales since the Second World War: the supply side revolution. Rural Hist 22:207–226

Martin J (2012) The transformation of lowland game shooting in England and Wales in the twentieth century: the neglected metamorphosis. The International Journal of the History of Sport 29:1141–1158

Mason LR, Bicknell JE, Smart J, Peach WJ (2020) The impacts of non-native gamebird release in the UK: an updated evidence review. RSPB Research Report No. 66. RSPB Centre for Conservation Science, Sandy, UK

PACEC (2006) The economic and environmentaleffect of sporting shooting. A report prepared by public and corporate economic consultants (PACEC) on behalf of BASC, CA, and CLA and in association with GCT

PACEC (2014) The value of shooting: the economic, environmental and social contribution of shooting sports to the UK. http://www.shootingfacts.co.uk/pdf/The-Value-of-Shooting-2014.pdf

Prieto R, Sánchez-García C, Tizado EJ, Alonso ME, Gaudioso VR (2018) Mate choice in red-legged partridges (Alectoris rufa L.) kept in commercial laying cages; does it affect laying output? Appl Anim Behav Sci 199:84–88

Prentis V (2020) Partridges and pheasants: imports. Written question – 73867. https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2020-07-14/73867. accessed 14 May 2021

Robertson PA, Mill AC, Rushton SP, McKenzie AJ, Sage RB, Aebischer NJ (2017) Pheasant release in Great Britain: long-term and large-scale changes in the survival of a managed bird. Eur J Wildl Res 63:100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-017-1157-7

Roos S, Smart J, Gibbons DW, Wilson JD (2018) A review of predation as a limiting factor for bird populations in mesopredator-rich landscapes: a case study of the UK. Biol Rev 93:1915–1937

RSPB (2007) The uplands: time to change? http://ww2.rspb.org.uk/Images/uplands_tcm9-166286.pdf. accessed 14 May 2021

Sage RB, Ludolf C, Robertson PA (2005) The ground flora of ancient semi-natural woodlands in pheasant release pens in England. Biol Cons 122:243–252

Sage RB, Hoodless AN, Woodburn MIA, Draycott RAH, Madden JR, Sotherton NW (2020) Summary review and synthesis—effects on habitats and wildlife of the release and management of pheasants and red-legged partridges on UK lowland shoots. Wildl Biol. https://doi.org/10.2981/wlb.00766

Sellers RM, Greenwood JJD (2019) Sir Richard Graham and the marking of ducks at Netherby, Cumberland, 1908–1933—an early bird-ringing project. Ringing Migr 33:86–93

Sutherland W, Armstrong-Brown S, Armsworth P, Brereton T, Brickland J, Campbell C, Watkinson A (2006) The identification of 100 ecological questions of high policy relevance in the UK. J Appl Ecol 43:617–627

Tapper SC (1992) Game heritage. The Game Conservancy Trust, Fordingbridge

The Game Conservancy Limited (1996) Gamebird releasing. The Game Conservancy Trust, Fordingbridge

Woodward ID, Aebischer NJ, Burnell D, Eaton MA, Frost TM, Hall C, Stroud DA, Noble DG (2020) Population estimates of birds in Great Britain and the United Kingdom. British Birds 113:69–104

World Bank (2020) United Kingdom Country Profile. https://databank.worldbank.org/views/reports/reportwidget.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&tbar=y&dd=y&inf=n&zm=n&country=GBR. accessed 14 May 2021

Acknowledgements

I thank Nicholas Aebischer and an anonymous reviewer for detailed comments and critiques of the MS. The APHAPR2020 dataset was obtained in conjunction with Dave Stone of Natural England. The NGC2019 dataset was kindly supplied by the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust.

Funding

This work was conducted during research time paid for by the University of Exeter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Madden, J.R. How many gamebirds are released in the UK each year?. Eur J Wildl Res 67, 72 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-021-01508-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-021-01508-z