Abstract

Pterocarya fraxinifolia, native to the southern Caucasus and adjacent areas, has been widely introduced in Europe. In this study, we investigate the following: (1) How did its current distribution form? (2) What are the past, current, and future suitable habitats of P. fraxinifolia? (3) What is the best conservation approach? Ecological niche modeling was applied to determine its climatic demands and project the distribution of climatically suitable areas during three periods of past, current, and future (2070) time. Then, an integrated analysis of fossil data was performed. Massive expansion of Pterocarya species between the Miocene and Pliocene facilitated the arrival of P. fraxinifolia to the southern Caucasus. The Last Glacial Maximum played a vital role in its current fragmented spatial distribution in the Euxinian and Hyrcanian regions with lower elevations, and Caucasian and Irano-Turanian regions with higher elevations. Climatic limiting factors were very different across these four regions. Future climate change will create conditions for the expansion of this species in Europe. Human activities significantly decreased the suitable area for P. fraxinifolia, especially in the Euxinian, Hyrcanian, and Irano-Turanian regions. Considering genetic diversity, climate vulnerability, and land utilization, the Euxinian, Hyrcanian, and Irano-Turanian regions have been recognized as conservation priority areas for P. fraxinifolia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The geographical ranges of species are not static in time, showing expansions and contractions that depend on changes in climate variability and human influence (Roces-Diaz et al. 2018; Scheffers et al. 2016). Warming climates and human activities have driven the success of alien plant invasions and a massive rearrangement of biota worldwide (Donaldson et al. 2014; Vila and Pujadas 2001). Moreover, the intentional movement of species for horticultural purposes may play an increasingly important role in the conservation of threatened species (Affolter 1997; Maunder et al. 2001). Relict trees (e.g. ginkgo, Liquidambar, Pterocarya, and Zelkova) have attracted the attention of naturalists and scientists for many centuries, and their cultivation in botanical gardens and arboreta has a long tradition (Maunder et al. 2001; Kozlowski et al. 2012).

Relict trees refer to trees that at an earlier time were abundant in a large area but now occur only in one or a few small areas (Milne and Abbott 2002). During the long period of the Pleistocene, most of Northern Europe was covered with extensive ice sheets (Bhagwat and Willis 2008; Willis 1996). Tree flora experienced a severe Plio-Pleistocene extinction in the European continent at the end of the Neogene due to: (1) the Mediterranean Sea and east–west-oriented mountains preventing southward migration of trees during cold stages (Svenning 2003; Tallis 1991), and (2) a climate shift from warm-temperate to summer-dry in the Mediterranean region from the middle Pliocene (Suc 1984; Svenning 2003).

Thus, a large proportion of tree genera disappeared in Europe, and only relict trees still survived to the present time in southwestern Eurasia (the Mediterranean and Euxino-Hyrcanian regions) (Kozlowski and Gratzfeld 2013; Medail and Diadema 2009; Tzedakis 1993; Tzedakis et al. 2013). One of the famous examples is Zelkova (Ulmaceae), which was widely distributed in Europe during the Miocene and contracted to the Sicily, Crete, and Euxino-Hyrcanian region (Kozlowski and Gratzfeld 2013). Other emblematic relict tree genera that followed a similar pattern are Aesculus, Forsythia, Liquidambar, Picea, and Pterocarya (Browicz and Zielinski 1982; Kozlowski et al. 2018a, b; Ozturk et al. 2008).

Ecological niche modeling (ENM) combines current natural occurrence data and environmental variables of species to estimate the geographic range of suitable habitats in the past, present, and future (Roberts and Hamann 2012). ENM has been widely applied in conservation biology and invasion biology to predict potential shifts in geographic ranges in response to climate change (Guisan et al. 2013; Song et al. 2019; Tang et al. 2017). A substantial amount of research has been conducted to understand the influence of ongoing climate warming on the geographic ranges of Mediterranean forest tree species (Montoya et al. 2007; Romo et al. 2017; Walas et al. 2019). In contrast, an important research gap exists for the Euxino-Hyrcanian region (Fig. 1a).

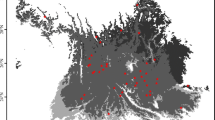

a Geographical distribution and four geographic regions of Pterocarya fraxinifolia from georeferenced data. EUX: Euxinian region; CAU: Caucasian region; HYR: Hyrcanian region; and ITU: Irano-Turanian region. b Map of climatically suitable habitats for Pterocarya fraxinifolia under current climate conditions (map shows suitable European, North African and West-Asiatic regions)

Pterocarya fraxinifolia (Caucasian wingnut) is a typical riparian relict tree (Figure S1, A-C) that currently exists in Euxino-Hyrcanian floristic regions and somewhat southerly dispersed localities. P. fraxinifolia is located mainly in the lowlands, occasionally reaching 600–800 m, and very rarely 1200 m (Kozlowski et al. 2018a). It is the only tree representative of the genus Pterocarya outside of eastern Asia, with special morphological characteristics (Figure S1, D-G). Thus, it is an important taxon for understanding the biogeography of East Asia versus southern European/West Asian disjunct patterns (Song et al. 2020). Locally, P. fraxinifolia provides riparian zone protection, and food for aquatic and terrestrial consumers. P. fraxinifolia has been introduced to Europe for horticulture and is now very commonly used in afforestation. For centuries, P. fraxinifolia habitats have been reduced, mainly due to conversion into agricultural land, and more recently because of gravel excavation and road and hydropower construction (Fink and Scheidegger 2018; Sabo et al. 2005; Yousefzadeh et al. 2018).

To derive systematic approaches for conservation, critical research is needed to better integrate fossil records, ENM, and phylogeographic surveys. Based on previous phylogeography and population genetics studies (Maharramova et al. 2018; Yousefzadeh et al. 2018), fossil synthesis and ENM were performed in this study. More specifically, the following questions were addressed: (1) What is the current geographic distribution of P. fraxinifolia and what are the climate characteristics of its potential niche? (2) What is the past distribution of climatically suitable habitats for P. fraxinifolia? (3) Where will potential niches be located in the future, considering three climate change scenarios? Finally, we assessed the reasonable manner for introducing P. fraxinifolia to Europe for conservation purposes.

Material and methods

Data collection

The past distribution of the genus Pterocarya in Europe was extracted and reviewed from the paleontological literature. Both pollen grains and macroremains (leaves and fruits) were considered for this study (Appendix). To better understand the historical distribution of Pterocarya, Europe was divided into five regions: Eastern Europe, Western Europe, Central Europe, Northern Europe, and Southern Europe (Table S1).

Data on the current natural distribution of P. fraxinifolia were extracted from the literature, herbaria, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF 2019), and our field survey. In total, 500 distribution records were collected, while 195 natural distribution records were finally identified as the present occurrence of P. fraxinifolia and used in our ENM (Fig. 1a; Table S2).

Ecological niche modeling

Modeling was performed using the maximum entropy method implemented in MaxEnt 3.3.2 (Elith et al. 2011; Philips et al. 2006) based on current species distribution data. A set of 19 bioclimatic variables at a 2.5 arc-min resolution that covered the P. fraxinifolia distribution range under current conditions were downloaded from the WorldClim website (Hijmans et al. 2005; www.worldclim.org). Seven climatic variables were removed from the analyses due to their significant correlation (r > 0.9), calculated using ENMTools v1.3 (Kolanowska 2013; Kolanowska and Konowalik 2014). Ultimately, 12 climatic variables were used as input data (Table 1; Hijmans et al. 2005). GIS data operations were carried out using ArcGIS 9.3 (ESRI) and QGIS 2.18.20 (QGIS Development Team 2018). Rasters with land cover were downloaded from the DIVA-GIS repository (Hijmans et al. 2001; www.diva-gis.org). These rasters allow comparison of the theoretical range of species with human-influenced areas.

Contemporary species–climate relationships were projected for the three past and three future layers using the procedures described above. Climate data layers were downloaded from the WorldClim database (Hijmans et al. 2005). Climatic data for the Last Interglacial (LIG) (approximately 125 ka BP) were adopted from Otto-Bliesner et al. (2006), while data for the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) (approximately 22 ka BP) and the Mid-Holocene (MH) (approximately 6 ka BP) were taken from Paleoclimate Modeling Intercomparison Project Phase II (Braconnot et al. 2007) (PMIP2, CCSM). For future climatic projections related to hypothetical climate change in 2070, the CCMS4 model was used (Gent et al. 2011) under three warming scenarios (Collins et al. 2013): Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 2.6 (+1 °C by 2100), RCP 4.5 (+1.8 °C by 2100), and RCP 8.5 (+3.7 °C by 2100).

The above procedures were performed for the whole data set, and the same bioclimatic variables were used in the analysis for each of the four geographic regions: (1) Euxinian, (2) Caucasian, (3) Hyrcanian, and (4) Irano-Turanian (Fig. 1a). Only locations within the selected region were used in each analysis. The four parts of the species geographic range were divided based on the fragmented geographic range and population genetic differences in this species (Maharramova et al. 2018; Mostajeran et al. 2017; Yousefzadeh et al. 2018; Zohary 1973). Finally, we also simulated the effects of artificial surfaces suitable for the establishment of this species.

Data analyses

Analysis results were mapped to represent climatic suitability ranging from 0 to 1 per grid cell. The maximum number of iterations was 10,000, and the convergence threshold was 0.00001. The ‘random seed’ option was used, which provided random test partitions and background subsets for each run. For each model run, 20% of the data were used to be set aside as the test points. Each run was performed as a bootstrap with 100 replicates, and the output was set to logistic (Elith et al. 2011; Philips et al. 2006).

Model predictions and the most important climatic variables were visualized using QGIS 2.14.21 ‘Lyon’ (QGIS Development Team 2018). The influence of particular climatic factors on the entire distribution and four geographic regions of P. fraxinifolia realized niches (Vetaas 2002) was verified using principal component analysis (PCA) implemented in R software (R Core Team 2016).

Results

Ecological niche modeling evaluation

The model was evaluated using the area under the curve (AUC) (Lobo et al. 2010). Our models showed excellent performance with AUC scores above 0.98, which indicates high reliability of the results. Common thresholds and corresponding omission rates for the evaluation of each model are presented in Table S3.

Current geographic range

Pterocarya fraxinifolia is characteristic of lowlands, riparian, and floodplain forests, mainly occurring between 0 and 400 m in the Euxinian (100%) and Hyrcanian (77.2%) regions, along the shores of the Black Sea and Caspian Sea. The populations in the Caucasian region are found mainly at elevations between 200 and 800 m (84.2%). Exceptionally, some can reach elevations above 400 m along the river valleys in the Hyrcanian region. The Irano-Turanian populations are only found above 400 m, mainly between 600 and 800 m (52.4%), and 19% is found higher than 1000 m, with a maximum elevation of 1730 m in the Zagros Mountains (Tables 2 and S2).

The actual P. fraxinifolia range is only half of its potential range that has been modeled based on climate data. The western edges of the Balkan Peninsula, southern part of Greece, and western Anatolian Peninsula lack natural populations of P. fraxinifolia but were modeled as having a suitable climate (Fig. 1b). After adding the effects of human activities (e.g. farmland and buildings), the actual suitable area for P. fraxinifolia decreased significantly (Figs. 2a and S2). Due to human activities, there are large suitable areas that disappeared in the Euxinian, Hyrcanian, and Irano-Turanian regions (Figs. 2a and S2).

When analyzed separately, different areas of potential suitable habitats were found in each of the distinguished regions with P. fraxinifolia occurrence (Fig. 2). Based on the data from the Hyrcanian region, small areas on the southern slopes of the Caucasus and Anatolian showed climatic similarities to the actual geographic range (Fig. 2b). However, the analysis based on climate parameters from the Euxinian (Fig. 2c), Caucasian (Fig. 2d), and Irano-Turanian (Fig. 2e) regions did not identify potential suitable habitats in other parts of the geographic range.

The average values for climatic factors that most impacted the potential habitats currently for P. fraxinifolia are presented in Table 1. The climatic conditions were different across the Euxinian, Caucasian, Hyrcanian, and Irano-Turanian regions. The highest differences were found in the Irano-Turanian region, which was placed in more continental regions with the lowest temperatures for the wettest quarter, the highest maximum temperatures during the warmest month, and the lowest precipitation level (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

The annual mean temperature and precipitation of the wettest month were the most important factors (contributing 28.5% and 24.4%, respectively) determining the current geographic range for P. fraxinifolia based on data from the entire distribution area (Table 3). Factors determining the current geographic range among the four regions were very different (Table 3). Annual precipitation (34.3%) was the most influential climatic factor for the actual habitats of P. fraxinifolia in the Euxinian region, followed by precipitation in the coldest quarter (23.1%). In the Caucasian region, annual mean temperature was the most important climate factor (35.2%). In the Hyrcanian region, precipitation of the wettest month (23.7%) and seasonality (23.1%) were equally important influential climatic factors. The annual mean temperature did not significantly influence the actual habitats in the Irano-Turanian region, while the decisive factor was precipitation in the coldest quarter (47.8%) and driest month (20.7%), which together were responsible for nearly 70% of the range prediction (Table 3).

Past geographic range

Fossil records for the genus Pterocarya in Europe are rich and common. The genus was represented by macroremains and pollen grains (Table 4). The first pollen grains were recorded from the Middle Eocene in western Europe and gradually discovered from rare records across Europe between the Late Miocene and the Late Oligocene. From the Miocene to the Early Pleistocene, pollen grains were common in all of Europe. Starting from the Middle Pleistocene, pollen grains became rare but were still reported from the interglacial periods, except for the last one (Table 4).

Macroremain Pterocarya fossils appeared significantly later, with the first record found from the Late Oligocene. The macroremains confirmed that different taxa of the genus were common in Europe between the Miocene and the Pliocene. During the Early Pleistocene, Pterocarya was still common in Southern Europe and gradually went extinct from this age on (Table 4).

Past niche modeling

During the LIG, temperatures in the current P. fraxinifolia geographic range were one degree lower with much larger annual oscillations (Table 5). Precipitation, however, was higher, both in the driest and wettest months (Table 5). The most suitable habitats during the LIG may have been more than 28 times larger than the current areas (Table 6). The suitable habitats for P. fraxinifolia covered nearly all Mediterranean and sub-Mediterranean regions, with a center of occurrence in the Euxino-Hyrcanian region, but also in the Irano-Turanian region (Fig. 4a). The suitable habitats in Europe, however, were probably not occupied by P. fraxinifolia during the LIG, with the exception of single sites in southeastern Europe.

During the LGM, the annual mean temperature in the suitable habitats was only 65% of the current temperature, and precipitation was 29% and 22% lower in the wettest and driest periods of the year, respectively (Table 5). The most suitable habitats during the LGM were 10 times smaller than the current suitable range (Table 6). During this time, P. fraxinifolia was pushed into restricted areas, where it survived until present in three fragmented localities (Fig. 4b). ENM analyses indicated that no areas had sufficiently suitable climate conditions in Europe during the LGM. Suitable habitats for P. fraxinifolia were detected mostly in the small areas of Hyrcanian and Irano-Turanian regions (Fig. 4b).

During the MH, the climate was very similar to today (Table 5). The most suitable habitat areas may have been 6.5 times larger (Table 6). The MH climate conditions were more suitable for P. fraxinifolia occurrence in a broader area than the current climate conditions, covering the eastern coastal region of the Balkan Peninsula in Europe (Fig. 4c).

Future climatically suitable areas

Areas with climatically suitable habitats (suitability above 0.5) for P. fraxinifolia occurrence in the future increased for each model that was analyzed. The RCP2.6 and RCP4.5 climate change scenarios accelerated the extension of suitable habitats in southeastern Europe (Fig. 5a and b). The most significant enlargement of suitable habitats was found under the RCP8.5 scenario, which projects an average temperature increase of 3.7 °C by 2100 (Fig. 5c). Under this scenario, suitable habitats would cover most of the southern and central Europe, and some parts of western, eastern, and northern Europe. Areas characterized with high suitability could be between 3.6 and 13.0 times greater than current ranges (Table 6). Compared to the current scenario, temperatures would increase significantly, while precipitation would be reduced in all three tested scenarios, especially under the most drastic scenario (RCP8.5), where precipitation of the wettest month will decrease by 10% (Table 5).

Discussion

Current geographic range and climatic determinants

In addition to the discovery of new P. fraxinifolia populations, especially in the Irano-Turanian region (Akhani and Salimian 2003; Avşar et al. 2004), the natural geographic range has also gradually improved. Currently, there are four main distribution centers for P. fraxinifolia: the Euxinian, Caucasian, Hyrcanian, and Irano-Turanian regions.

In the Euxinian region, P. fraxinifolia is a component of humid broadleaved forests on plains and/or along riversides and grows with other broadleaved tree taxa from the genera Acer, Alnus, Carpinus, Diospyros, Ficus, and Quercus (Kozlowski et al. 2018a; Nakhutsrishvili 2012). The Caucasian region is on the southern slopes of the Great Caucasus between the Alazani and Shamakhi Rivers. Along the river valley, P. fraxinifolia is located at higher elevations in deciduous forests than the other genera mentioned above. In this region, species can form sporadic narrow belts of riparian woodlands between 800 and 1200 m (Iljinskaya 1953).

The most important region for P. fraxinifolia is the Hyrcanian. Here, populations of P. fraxinifolia have the largest altitudinal range and can grow from depressions of − 20 m up to 600 m, with a maximum elevation of 1100 m (Yousefzadeh et al. 2018). This region is also a reservoir of P. fraxinifolia genetic diversity (Maharramova et al. 2018). Areas within the Irano-Turanian region are poorly studied and the most atypical, with P. fraxinifolia reaching a maximum elevation of 1730 m (Akhani et al. 2010; Akhani and Salimian 2003).

The different climate conditions controlling P. fraxinifolia occurrence in the four regions described above may have facilitated its adaptation during a long period of spatial separation. This is partly seen in the pattern of genetic differentiation for the species and its division into at least two groups: the Hyrcanian and Euxinian-Caucasian regions (Maharramova et al. 2018). The Irano-Turanian region needs to be given greater protection, due to the special climatic demands, which differ from those of the other three regions.

Our analyses showed that climatic conditions in the Hyrcanian region provided very broad potential suitable habitats for P. fraxinifolia, which was not the case in the Euxinian and Caucasian regions. Surprisingly, climate conditions in the Irano-Turanian region also provided broad potential suitable habitats. Different climatic demands among fragmented regions have been reported for several other species (Anderson and Raza 2010; Jezkova et al. 2016; Walas et al. 2019). Differentiation of climatic demands and spatial isolation resulted in genetic differentiation among populations (Anderson and Raza 2010; Jezkova et al. 2016).

Historic expansion and contraction: Integrating fossil records, ENM and phylogeographic surveys

Fossils provide the best evidence for a species within a past window of space and time. According to the fossil records, it is highly likely that Pterocarya began to appear in Europe during the Oligocene. The expansion of Pterocarya in Europe may have occurred during the Late Oligocene and Early Miocene. During the Miocene and Pliocene, Pterocarya became common among European wetland vegetation (Mai 1995; Reumer and Wessels 2003). Fossil records indicate that Pterocarya was inferred to still have a large distribution throughout Europe by the Early Pleistocene (Hrynowiecka and Winter 2016; Segota1967; Stachowicz-Rybka et al. 2017). Due to significant climate cooling from the end of the Miocene and especially the end of the Pliocene, a major ice sheet expansion occurred in Europe (Zachos et al. 2001). Coincidentally, the most recent common ancestor of all P. fraxinifolia haplotypes has been dated to the Late Pliocene (Maharramova et al. 2018).

During the LIG, climatically suitable habitats shrank southward to southern Europe. Along with ice sheet expansion, Pterocarya disappeared from most of the areas in Europe during the Pleistocene. From the Middle Pleistocene, fossil records of pollen grains became rare in Europe and macroremains were found only in some southern European localities (Follieri 1958; Hrynowiecka and Szymczyk 2011; Magri et al. 2017; Martinetto 2015; Suc et al. 2018). The positive results between ENM and fossil records suggest that the first great contraction for Pterocarya occurred during the Middle Pleistocene.

The second major contraction for Pterocarya occurred during the LGM. The lack of fossil records in Europe and the modeling results from this study indicated that the LGM was absolutely devastating for Pterocarya and other relict trees in Europe. During this time, a large number of relict trees disappeared from Europe or retreated to Mediterranean areas, such as Zelkova, Liquidambar, Forsythia, and Parrotia (Kozlowski and Gratzfeld 2013; Ozturk et al. 2008).

Our results showed that during the LGM, P. fraxinifolia occupied an extremely small area with suitable climatic conditions. The low-to-intermediate levels of genetic diversity in P. fraxinifolia further proved that there were very small climatic microrefugia for this species during the LGM (Maharramova et al. 2018). The Euxinian and Hyrcanian regions were modeled as climatic refugia during the LGM, so the hypothesis that colonization from the southeast (Hyrcanian region) to northwest (Colchis) occurred before the LGM was supported by this study (Maharramova et al. 2018). As the oldest population, the Hyrcanian region with the highest genetic diversity to the best of our knowledge is the key area for conservation.

The current warm period during the Holocene may have provided favorable conditions for P. fraxinifolia expansion. Compared with ENM for the LGM, the suitable habitats are more than 70 times larger for MH. Combined with phylogeographic surveys (Maharramova et al. 2018), the Caucasian became a new region for P. fraxinifolia that expanded from the Euxinian region during the Holocene. Currently, the other three regions are also much larger than the suitable habitats during the LGM.

The future of P. fraxinifolia under changes in climate and land utilization

Increasing annual mean temperature, which is the most important bioclimatic variable for P. fraxinifolia, may create suitable conditions for this species in large areas of Europe. Suitable habitat expansions have been detected for other tree species, mainly from the nemoral biome (Dyderski et al. 2018; Svenning et al. 2008), but they restrict their geographic ranges within the strictly Mediterranean biome (Romo et al. 2017; Walas et al. 2019).

However, because the species has not expanded significantly since the LGM, the extensive presence of new suitable habitats in Europe in the future does not mean that P. fraxinifolia will colonize these areas. Generally, the genus Pterocarya is a Cenozoic relict genus of the Northern Hemisphere, which is believed to have climate niche conservatism (Shiono et al. 2018). The tree diversity of Europe is to a large extent a result of postglacial dispersal limitation and not exclusively by climate habitat availability and suitability (Svenning and Skov 2007). Furthermore, with riparian habitat fragmentation, it will be difficult for the species to spread to potentially suitable habitats (Fink and Scheidegger 2018). Land-use change will also reduce Caucasian wingnut dispersal rates and prevent settling within potential habitats (Miller and McGill 2018). Thus, we propose that climatic opportunities alone likely will not facilitate the natural expansion of the species, even within its current range.

Holocene warming is considered to be the main reason behind successful European recolonization by Quercus spp., Castanea sativa, Corylus avellana, Tilia spp., Ulmus spp. and others (Brewer et al. 2002; Kunes et al. 2008; Roces-Diaz et al. 2018). The failure of the return P. fraxinifolia to Europe was supposedly due to its limitations in migration and seed dispersal, which inhibited its ability to return to Europe naturally (Prilipko 1961; Tarkhnishvili et al. 2012).

Within the suitable habitat areas, arable land and urbanized areas occupied a considerable proportion, indicating that there is a large disturbance of human activities in the suitable habitats of P. fraxinifolia. Thus, the species will face a more severe survival situation in the future.

Effective conservation of relict P. fraxinifolia from microrefugia and avoidance of invasion risk legitimately

Historical expansions and contractions during the Quaternary, especially the LGM, led to the formation of the current disjunctive pattern of P. fraxinifolia. Since the Anthropocene, human activities have compressed suitable areas, especially in the Euxinian region. Combined with the results of this study and population genetics, we could provide a clear idea for the in situ conservation of P. fraxinifolia. The Caucasian region has the most stable habitat, with less impact from human activities. Conservation efforts need to focus on the three climatic microrefugia during the LGM: (1) the Hyrcanian region possessed high genetic diversity, (2) the Euxinian region lost most of its habitat due to human activities, and (3) the Irano-Turanian region has special climatic demands that have been poorly studied.

Pterocarya fraxinifolia has been planted in European gardens, forests, and parks for centuries (Sukopp et al. 2015). Many other woody species introduced to Europe for agriculture, forestry, medicine, and decorative purposes (Essl et al. 2018), such as Abies grandis, Acer negundo, Ailanthus altissima, Eucalyptus spp., Quercus rubra, Robinia pseudoacacia, and Tsuga heterophylla, have already become invasive in Europe (Krumm and Vitkova 2016; Fanal et al. 2021). Identifying emerging invasive species is a priority to implement early preventive and control actions. This study indicated that P. fraxinifolia has a wide range of future suitable habitats in Europe. Many wetland plants fit the definition of being invasive as species that rapidly increase their spatial distribution by expanding into native plant communities (Zedler and Kercher 2004). The high demands of P. fraxinifolia for light and soil humidity will help seedlings establish and provide favorable conditions for rapid growth (Prilipko 1961). Population expansions of nonnative P. fraxinifolia have already been observed, such as in Belgium, France, Germany, Poland, Switzerland, etc. (Andeweg 2013; Sukopp et al. 2015; Verloove 2011). In the future, the invasiveness (impact on biodiversity and ecosystems) of life traits of the species needs to be assessed. Thus, it would be very important to carry out a detailed survey of ex situ collections and forest plantations of P. fraxinifolia across the whole European continent, as well as monitor their dynamics.

Conclusions

Pterocarya fraxinifolia is a typical element of riparian and floodplain forests in lowlands of the Euxinian, Caucasian, and Irano-Turanian regions. The annual mean temperature and precipitation of the wettest month are the most important factors determining the current distribution of this relict tree species. However, climatic limiting factors clearly diverged among the four main distributed areas. Interestingly, its actual range is only half of the potential range of this taxon in Western Eurasia, with large parts of the Balkan Peninsula, Greece and Anatolia without P. fraxinifolia. However, these areas possess suitable climatic conditions. In the past, P. fraxinifolia possessed the largest suitable habitats during LIG (more than 28 times larger). This area was dramatically reduced during the LGM (10 times smaller than today) with only three fragmented localities in the Hyrcanian and Irano-Turanian regions. Accelerated human-made climate change will significantly increase the suitable habitats for P. fraxinifolia. Under the RCP8.5 scenario, for example, the taxon would cover most of southern and central Europe, as well as large parts of western, eastern, and even northern Europe. However, strong fragmentation of riparian habitats and land use changes for agriculture and urbanization will significantly slow or even make impossible the natural expansion of the species to the West. Nevertheless, since the species is largely planted in parks, forests, and gardens, monitoring such artificial plantations, and potential sources of expansion would be highly desirable.

References

Affolter JM (1997) Essential role of horticulture in rare plant conservation. Hortscience 32:29–34. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.32.1.29

Akhani H, Salimian M (2003) An extant disjunct stand of Pterocarya fraxinifolia (Juglandaceae) in the central Zagros Mountains, W Iran. Willdenowia 33:113–120. https://doi.org/10.3372/wi.33.33111

Akhani H, Djamali M, Ghorbanalizadeh A, Ramezani E (2010) Plant biodiversity of Hyrcanian relict forests, N Iran: an overview of the flora, vegetation, palaeoecology and conservation. Pak J Bot 42:231–258

Anderson RP, Raza A (2010) The effect of the extent of the study region on GIS models of species geographic distributions and estimates of niche evolution: preliminary tests with montane rodents (genus Nephelomys) in Venezuela. J Biogeogr 37:1378–1393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02290.x

Andeweg R (2013) Kaukasische vleugelnoot komt uit de schaduw. Straatgras 25:36–37

Avşar MD, Ok T, Gündeşli A (2004) Kahramanmaraş-dereköy yöresindeki bir dişbudak (Pterocarya fraxinifolia (Poiret) Spach) Topluluğunda kahramanmaraş sütçü imam üniversitesi. J Sci Eng 7:73–77

Bhagwat SA, Willis KJ (2008) Species persistence in northerly glacial refugia of Europe: a matter of chance or biogeographical traits? J Biogeogr 35:464–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01861.x

Binka K, Nitychoruk J, Dzierzek J (2003) Parrotia persica C.A.M. (Persian witch hazel, Persian ironwood) in the Mazovian (Holsteinian) Interglacial of Poland. Grana 42:227–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/00173130310016220

Braconnot P, Otto-Bliesner B, Harrison S, Joussaume S, Peterchmitt JY, Abe-Ouchi A, Crucifix M, Driesschaert E, Fichefet T, Hewitt CD, Kageyama M, Kitoh A, Laine A, Loutre MF, Marti O, Merkel U, Ramstein G, Valdes P, Weber SL, Yu Y, Zhao Y (2007) Results of PMIP2 coupled simulations of the mid-holocene and last glacial maximum – Part 1: experiments and large-scale features. Climate Past 3:261–277

Brewer S, Cheddadi R, de Beaulieu JL, Reille M (2002) The spread of deciduous Quercus throughout Europe since the last glacial period. For Ecol Manage 156:27–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00646-6

Browicz K, Zielinski J (1982) Chorology of trees and shrubs in south-west Asia and adjacent regions, vol I. Polish Scientific Publisher, Poznan

CIA World Factbook (2019). Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/

Collins M, Knutti R, Arblaster J, Dufresne JL, Fichefet T, Friedlingstein P, Gao XJ, Gutowski WJ, Johns T, Krinner G, Shongwe M, Tebaldi C, Weaver AJ, Wehner MF, Allen MR, Andrews T, Beyerle U, Bitz CM, Bony S, Booth BBB (2013) Long-term climate change: projections, commitments and irreversibility. In: Stocker TF, Qin DH, Plattner GK, Tignor MMB, Allen SK, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley PM (eds) Climate change 2013 - The physical science basis: contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, New York NY USA, pp 1029–1136

Donaldson JE, Hui C, Richardson DM, Robertson MP, Webber BL, Wilson JRU (2014) Invasion trajectory of alien trees: the role of introduction pathway and planting history. Glob Chang Biol 20:1527–1537. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12486

Dyderski MK, Paź S, Frelich LE, Jagodziński AM (2018) How much does climate change threaten European forest tree species distributions? Glob Chang Biol 24:1150–1163. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13925

Elith J, Phillips SJ, Hastie T, Dudik M, Chee YE, Yates CJ (2011) A statistical explanation of MaxEnt for ecologists. Divers Distrib 17:43–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2010.00725.x

Essl F, Bacher S, Genovesi P, Hulme PE, Jeschke JM, Katsanevakis S, Kowarik I, Kuhn I, Pysek P, Rabitsch W, Schindler S, van Kleunen M, Vila M, Wilson JRU, Richardson DM (2018) Which taxa are alien? Criteria, applications, and uncertainties. Bioscience 68:496–509. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biy057

Eurovoc (2018). Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eurovoc

Fanal A, Mahy G, Fayolle A, Monty A (2021) Arboreta reveal the invasive potential of several conifer species in the temperate forests of western Europe. NeoBiota 64:23–42. https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.64.56027

Fink S, Scheidegger C (2018) Effects of barriers on functional connectivity of riparian plant habitats under climate change. Ecol Eng 115:75–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2018.02.010

Follieri M (1958) La foresta colchica fossile di Riano Romano: I. Studio dei fossili vegetali macroscopici. Annali Di Botanica (rome) 26:129–142

Follieri M (1962) La foresta colchica fossile di Riano Romano. II Analisi Polliniche Annali Di Botanica 27:245–280

GBIF (2019) GBIF Occurrence Download, https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.qxxlnk.

Gent PR, Danabasoglu G, Donner LJ, Holland MM, Hunke EC, Jayne SR, Lawrence DM, Neale RB, Rasch PJ, Vertenstein M, Worley PH, Yang ZL, Zhang MH (2011) The community climate system model version 4. J Clim 24:4973–4991. https://doi.org/10.1175/2011JCLI4083.1

Gruas-Cavagnetto C (1978) Étude palynologique de l’Éocène du Bassin Anglo-Parisien. Mémoires De La Société Géologique De France 56:1–64

Guisan A, Tingley R, Baumgartner JB, Naujokaitis-Lewis I, Sutcliffe PR, Tulloch AIT, Regan TJ, Brotons L, McDonald-Madden E, Mantyka-Pringle C, Martin TG, Rhodes JR, Maggini R, Setterfield SA, Elith J, Schwartz MW, Wintle BA, Broennimann O, Austin M, Ferrier S, Kearney MR, Possingham HP, Buckley YM (2013) Predicting species distributions for conservation decisions. Ecol Lett 16:1424–1435. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12189

Hijmans R, Cruz M, Rojas E, Guarino L (2001) DIVA-GIS version 1.4: A geographic information system for the analysis of biodiversity data, manual. International Potato Center (CIP)

Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A (2005) Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol 25:1965–1978. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1276

Hrynowiecka A, Szymczyk A (2011) Comprehensive palaeobotanical studies of lacustrine-peat bog sediments from the Mazovian/Holsteinian interglacial at the site of Nowiny Zukowskie (SE Poland) – preliminary study. Bullet Geograp, Phy Geogra Series 4:21–45. https://doi.org/10.2478/bgeo-2011-0002

Hrynowiecka A, Winter H (2016) Palaeoclimatic changes in the Holsteinian Interglacial (Middle Pleistocene) on the basis of indicator-species method – Palynological and macrofossils remains from Nowiny Żukowskie site (SE Poland). Quat Int 409:255–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2015.08.036

Iljinskaya IA (1953) Monograph of the genus Pterocarya Kunth. Flora Et Systematica Plantae Vasculares 10:7–123

Jezkova T, Jaeger JR, Oláh-Hemmings V, Jones KB, Lara-Resendiz RA, Mulcahy DG, Riddle BR (2016) Range and niche shifts in response to past climate change in the desert horned lizard Phrynosoma platyrhinos. Ecography 39:437–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.01464

Kolanowska M (2013) Niche conservatism and the future potential range of Epipactis helleborine (Orchidaceae). PLoS ONE 8:e77352. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0077352

Kolanowska M, Konowalik K (2014) Niche conservatism and future changes in the potential area coverage of Arundina graminifolia, an invasive Orchid species from Southeast Asia. Biotropica 46:157–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.12089

Kovar-Eder J (2003) Vegetation dynamics in Europe during the Neogene. In: Reumer, JWF, Wessels W (Eds), Distribution and migration of Tertiary mammals in Eurasia. A volume in honour of Hans de Bruijn. Deinsea 10:373–392.

Kozlowski G, Gratzfeld J (2013) Zelkova - an ancient tree. Global status and conservation action. Natural History Museum Fribourg, Fribourg.

Kozlowski G, Gibbs D, Huan F, Frey D, Gratzfeld J (2012) Conservation of threatened relict trees through living ex situ collections: lessons from the global survey of the genus Zelkova (Ulmaceae). Biodivers Conserv 21:671–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-011-0207-9

Kozlowski G, Bétrisey S, Song YG (2018a) Wingnuts (Pterocarya) and walnut family. Relict trees: linking the past, present and future. Natural History Museum Fribourg, Fribourg.

Kozlowski G, Bétrisey S, Song YG, Fazan L, Garfi G (2018b) The Red List of Zelkova. Natural History Museum Fribourg, Fribourg

Krumm F, Vitkova L (2016) Introduced tree species in European forests: opportunities and challenges. European Forest Institute, Freiburg

Krupinski KM (1995) Stratygrafia pyłkowa i sukcesja roślinności interglacjału mazowieckiego w świetle badań osadów z Podlasia. Acta Geographica Lodziensia 50:1–189

Kunes P, Pokorny P, Sida P (2008) Detection of the impact of early Holocene hunter-gatherers on vegetation in the Czech Republic, using multivariate analysis of pollen data. Veg Hist Archaeobot 17:269–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-007-0119-5

Kvacek Z, Teodoridis V (2007) Tertiary macrofloras of the Bohemian Massif: a review with correlations within Boreal and Central Europe. Bull Geosci 82:383–408. https://doi.org/10.3140/bull.geosci.2007.04.383

Lenz OK, Wilde V, Riegel W (2011) Short-term fluctuations in vegetation and phytoplankton during the Middle Eocene greenhouse climate: a 640-kyr record from the Messel oil shale (Germany). Geol Rundsch 100:1851–1874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-010-0609-z

Lobo JM, Jiménez-Valverde A, Hortal J (2010) The uncertain nature of absences and their importance in species distribution modelling. Ecography 33:103–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.06039.x

Magri D, Rita FD, Aranbarri J, Fletcher W, Gonzalez-Samperiz P (2017) Quaternary disappearance of tree taxa from Southern Europe: timing and trends. Quat Sci Rev 163:23–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2017.02.014

Maharramova E, Huseynova I, Kolbaia S, Gruenstaeudl M, Borsch T, Muller LAH (2018) Phylogeography and population genetics of the riparian relict tree Pterocarya fraxinifolia (Juglandaceae) in the South Caucasus. Syst Biodivers 16:14–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2017.1333540

Mai DH (1995) Tertiäre Vegetationsgeschichte Europas Jena. Gustav Fischer Verlag, New York, Stuttgart

Martinetto E (2015) Monographing the Pliocene and early Pleistocene carpofloras of Italy: methodological challenges and current progress. Palaeontographica B 293:57–99. https://doi.org/10.1127/palb/293/2015/57

Maunder M, Higgens S, Culham A (2001) The effectiveness of botanic garden collections in supporting plant conservation: a European case study. Biodivers Conserv 10:383–401. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016666526878

Medail F, Diadema K (2009) Glacial refugia influence plant diversity patterns in the Mediterranean Basin. J Biogeogr 36:1333–1345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.02051.x

Miller KM, McGill BJ (2018) Land use and life history limit migration capacity of eastern tree species. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 27:57–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12671

Milne RI, Abbott RJ (2002) The origin and evolution of Tertiary relict floras. Adv Bot Res 38:281–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2296(02)38033-9

Montoya D, Rodriguez MA, Zavala MA, Hawkins RA (2007) Contemporary richness of holarctic trees and the historical pattern of glacial retreat. Ecography 30:173–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0906-7590.2007.04873.x

Mostajeran F, Yousefzadeh H, Davitashvili N, Kozlowski G, Akbarinia M (2017) Phylogenetic relationships of Pterocarya (Juglandaceae) with an emphasis on the taxonomic status of Iranian populations using ITS and trnH-psbA sequence data. Plant Biosyst 151:1012–1021. https://doi.org/10.1080/11263504.2016.1219416

Muller J (1981) Fossil pollen records of extant angiosperms. Bot Rev 47:1–142. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02860537

Nakhutsrishvili G (2012) The Vegetation of Georgia (South Caucasus). Springer, Stuttgart

Nitychoruk J (1994) Stratygrafia plejstocenu i paleogeomorfologia południowego Podlasia. Rocznik Międzyrzecki 26:23–107

Otto-Bliesner BL, Marshall SJ, Overpeck JT, Miller GH, Hu A, CAPE Last Interglacial Project members (2006) Simulating Arctic climate warmth and icefield retreat in the last interglaciation. Science 311:1751–1753

Ozturk M, Celik A, Guvensen A, Hamzaoglu E (2008) Ecology of tertiary relict endemic Liquidambar orientalis Mill. forests. For Ecol Manage 256:510–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.01.027

Phillips SJ, Anderson RP, Schapire RE (2006) Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol Modell 190:231–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026

Prilipko LI (1961) Pterocarya Kunth. In: Gulisashvili VZ (ed) Dendroflora Kavkaza, 2. Akademia Nuak Gruzinskoy SSR, Tbilisi

QGIS Development Team (2018) QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. Available from: http://qgis.osgeo.org

R Core Team (2016) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available from: www.R-project.org

Reumer JWF, Wessels W eds, (2003) Distribution and migration of Tertiary mammals in Eurasia. Deinsea: Annual of the Natural History Museum Rotterdam, 10, pp. 576

Roberts DR, Hamann A (2012) Predicting potential climate change impacts with bioclimate envelope models: a palaeoecological perspective. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 21:121–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00657.x

Roces-Diaz JV, Jimenez-Alfaro B, Chytry M, Diaz-Varela ER, Alvarez-Alvarez P (2018) Glacial refugia and mid-Holocene expansion delineate the current distribution of Castanea sativa in Europe. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 491:152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.12.004

Romo A, Iszkuło G, Taleb MS, Walas Ł, Boratyński A (2017) Taxus baccata in Morocco: a tree in regression in its southern extreme. Dendrobiology 78:63–74

Sabo JL, Sponseller R, Dixon M, Gade K, Harms T, Heffernan J, Jani A, Katz G, Soykan C, Watts J, Welter J (2005) Riparian zones increase regional species richness by harboring different, not more, species. Ecology 86:56–62. https://doi.org/10.1890/04-0668

Scheffers BR, Meester LD, Bridge TCL, Hoffmann AA, Pandolfi JM, Corlett RT, Butchart SHM, Pearce-Kelly P, Kovacs KM, Dudgeon D, Pacifici M, Rondinini C, Foden WB, Martin TG, Mora C, Bickford D, Watson JEM (2016) The broad footprint of climate change from genes to biomes to people. Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf7671

Segota T (1967) Paleotemperature changes in the upper and middle Pleistocene. E&G Quater Sci J 18:127–141

Shiono T, Kusumoto B, Yasuhara M, Kubota Y (2018) Roles of climate niche conservatism and range dynamics in woody plant diversity patterns through the Cenozoic. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 27:865–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12755

Song YG, Petitpierre B, Deng M, Wu JP, Kozlowski G (2019) Predicting climate change impacts on the threatened Quercus arbutifolia in montane cloud forests in southern China and Vietnam: conservation implications. For Ecol Manage 444:269–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.04.028

Song YG, Li Y, Meng HH, Fragnière Y, Ge BJ, Sakio H, Yousefzadeh H, Bétrisey S, Kozlowski G (2020) Phylogeny, taxonomy, and biogeography of Pterocarya (Juglandaceae). Plants 9:1524. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9111524

Stachowicz-Rybka R, Pidek IA, Żarski M (2017) New palaeoclimate reconstructions based on multidisciplinary investigation in the Ferdynandów 2011 stratotype site (eastern Poland). Geolog Quart 61:276–290. https://doi.org/10.7306/gq.1353

Suc JP (1984) Origin and evolution of the Mediterranean vegetation and climate in Europe. Nature 307:429–432. https://doi.org/10.1038/307429a0

Suc JP, Popescu SM, Fauquette S, Bessedik M, Jimenez-Moreno G, Taoufiq NB, Zheng Z, Medail F, Klotz S (2018) Reconstruction of Mediterranean flora, vegetation and climate for the last 23 million years based on an extensive pollen dataset. Ecol Mediterr 44:53–85

Sukopp H, Bocker R, Brande A (2015) Die Kaukasische Flugelnuss in und um Berlin. Verh Bot Ver Berlin Brandenburg 148:31–81

Svenning JC (2003) Deterministic Plio-Pleistocene extinctions in the European cool-temperate tree flora. Ecol Lett 6:646–653. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00477.x

Svenning JC, Skov F (2007) Ice age legacies in the geographical distribution of tree species richness in Europe. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 16:234–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2006.00280.x

Svenning JC, Normand S, Kageyama M (2008) Glacial refugia of temperate trees in Europe: insights from species distribution modelling. J Ecol 96:1117–1127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2008.01422.x

Tallis JH (1991) Plant community history: long-term changes in plant distribution and diversity. Chapman and Hall, London

Tang CQ, Dong YF, Herrando-Moraira S, Matsui T, Ohashi H, He LY, Nakao K, Tanaka N, Tomita M, Li XS, Yan HZ, Peng MC, Hu J, Yang RH, Li WJ, Yan K, Hou XL, Zhang ZY, Lopez-Pujol J (2017) Potential effects of climate change on geographic distribution of the tertiary relict tree species Davidia involucrata in China. Sci Rep 7:43822. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep43822

Tarkhnishvili D, Gavashelishvili A, Mumladze L (2012) Palaeoclimatic models help to understand current distribution of Caucasian forest species. Biol J Linn Soc Lond 105:231–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.2011.01788.x

Traiser C, Dalitz H, Krause M, Lange J, Roth-Nebelsick A, Kovar-Eder J (2019) Digiphyll - A digital tool for competence building in palaeobotany for teaching and research. Version 1.0; Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart. Available from: http://digiphyll.smns-bw.org

Tzedakis PC (1993) Long-term tree populations in northwest Greece through multiple quaternary climatic cycles. Nature 364:437–440. https://doi.org/10.1038/364437a0

Tzedakis PC, Emerson BC, Hewitt GM (2013) Cryptic or mystic? Glacial tree refugia in northern Europe. Trends Ecol Evol 28:696–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2013.09.001

Verloove F (2011) Fraxinus pennsylvanica, Pterocarya fraxinifolia en andere opmerkelijke uitheemse rivierbegeleiders in België en Noord-west Frankrijk. Dumortiera 99:1–10

Vetaas OR (2002) Realized and potential climate niches: a comparison of four Rhododendron tree species. J Biogeigr 29:545–554. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.2002.00694.x

Vila M, Pujadas J (2001) Land-use and socio-economic correlates of plant invasions in European and North African countries. Biol Conserv 100:397–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00047-7

Walas Ł, Sobierajska K, Ok T, Dönmez AA, Kanoğlu SS, Dagher-Kharrat MB, Douaihy B, Romo A, Stephan J, Jasinska AK, Boratyński A (2019) Past, present and future geographic range of an oro-Mediterranean Tertiary relict: The Juniperus drupacea case study. Reg Environ Chang 19:1507–1520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-019-01489-5

Westerhoff WE, Cleveringa P, Meijer T, van Kolfschoten T, Zagwijn WH (1998) The lower pleistocene fluvial (clay) deposits in the Maalbeek pit near Tegelen, The Netherlands. Mededelingen Nederlands Instituut Voor Toegepaste Geowetenschappen TNO 60:35–70

Willis KJ (1996) Where did all the flowers go? The fate of temperate European flora during glacial periods. Endeavour 20:110–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-9327(96)10019-3

Winter H (2001) Nowe stanowisko interglacjału augustowskiego w północno-wschodnej Polsce. In: Kostrzewski, A. (Ed.), Geneza, litologia i stratygrafia utworów czwartorzędowych 3, Seria Geografia 64:439–450

Worobiec E, Gedl P (2018) Upper Eocene palynoflora from Łukowa (SE Poland) and its palaeoenvironmental context. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 492:134–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.12.019

Yousefzadeh H, Rajaei R, Jasinska A, Walas L, Fragniere Y, Kozlowski G (2018) Genetic diversity and differentiation of the riparian relict tree Pterocarya fraxinifolia (Juglandaceae) along altitudinal gradients in the Hyrcanian forest (Iran). Silva Fennica 52:5–10000

Zachos J, Pagani M, Sloan L, Thomas E, Billups K (2001) Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science 292:686–693. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1059412

Zastawniak E, Lancucka-Srodoniowa M, Baranowska-Zarzycka Z, Hummel A, Lesiak M (1996) Flora megasporowa, liściowa i owocowo-nasienna. In: Malinowska, L. & Piwocki, M. (Eds), Budowa Geologiczna Polski, T. 3, Atlas Skamieniałości Przewodnich i Charakterystycznych, 3a, kenozoik, trzeciorzęd, neogen. Polska Agencja Ekologiczna, Warszawa, pp 855–940.

Zedler JB, Kercher S (2004) Causes and consequences of invasive plants in wetlands: opportunities, opportunists, and outcomes. Crit Rev Plant Sci 23:431–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352680490514673

Zohary M (1973) Geobotanical foundations of the Middle East. Fischer, Stuttgart

Funding

The State Scholarship Fund to pursue Yi-Gang Song's PhD study is provided by the program of China Scholarship Council (CSC) (File No. 201608310121). This work was supported by (1) the W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, Kraków, Poland (under statutory activity), (2) the Institute of Dendrology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Kórnik, Poland (under statutory activity), (3) the Fondation Franklinia, and (4) Shanghai Municipal Administration of Forestation and City Appearances, Grant Nos. G212406 and G202401.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Andrés Bravo-Oviedo.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix

Fossil record synthesis of Pterocarya in Europe

Rich fossil record of the genus Pterocarya in Europe includes both pollen grains and macroremains (mainly isolated leaflets and fruits, rarely wood, and exceptionally also inflorescences). The macroremains of Pterocarya in the European Paleogene and Neogene are represented by fossil leaflets, usually classified as fossil-species Pterocarya paradisiaca (Unger) Ilinskaya, rarely also as Pterocarya castaneifolia (Goeppert) Schlechtendal and Pterocarya denticulata (Weber) Heer, and fossil fruits (winged nutlets) described as Pterocarya limburgensis C. Reid & E. Reid (Pterocarya raciborskii Zabłocki). Early Pleistocene fruits of Pterocarya were reported usually as Pterocarya limburgensis. P. paradisiaca morphologically is similar to the contemporary P. fraxinifolia (Traiser et al. 2019) and fruits of P. limburgensis are compared both to winged nuts of P. hupehensis and P. fraxinifolia (Martinetto 2015).

To better describe the distribution of fossils, the whole Europe were divided into five regions: Eastern Europe (EE), Western Europe (WE), Central Europe (CE), Northern Europe (NE) and Southern Europe (SE), based on the Eurovoc and CIA World Factbook (CIA 2019; Eurovoc 2018).

Pterocarya pollen grains are known since Paleogene. The oldest, rather sparse pollen grains were recorded from Eocene localities (ca. 47 Ma) (Gruas-Cavagnetto 1978; Lenz et al. 2011; Muller 1981; Worobiec and Gedl 2018). Although Oligocene localities are more numerous, pollen grains of Pterocarya were still insignificant components of the palynofloras. The role of Pterocarya become significant in the pollen floras of Neogene period (Miocene and Pliocene), thus indicating the common occurrence of the wingnut in the wetland vegetation of Europe in this epoch. During the Pleistocene, pollen grains of Pterocarya were found in NE, WE, CE and EE in all interglacial phases, until the Holsteinian (Binka et al. 2003; Hrynowiecka and Winter 2016; Krupinski 1995; Nitychoruk 1994; Segota 1967; Stachowicz-Rybka et al. 2017; Winter 2001). In Southern Europe, Pterocarya pollen was found in most profiles, ranging from very low frequencies, from less than 2% to even more than 50% in the Middle Pleistocene site of Riano (Follieri 1962), where also macroremains of wingnut were discovered (Follieri 1958).

Pterocarya was present until 0.4 Ma in almost all studied European and south-west Asiatic sites, e.g. from Anatolia, Central Italy, Greece, French Massif Central, French Alps, and in two Portuguese marine cores. After this time its distribution was severely fragmented resulting from its disappearance until probable last recorded occurrence of the species during the Eemian interglacial (Magri et al. 2017). The research of Suc et al. (2018), based on two offshore cores including long pollen records in the Gulf of Lions and near the Gargano Peninsula (Italy), shows that the Pterocarya occurred during each warm phase up to the end of the Eemian. It was absent in all the colder phases since 0.5 Ma, which proves its extreme frailty during the recent glacial–interglacial cycles. However, the only scarce presence of the species was proved by pollen and macroremains from southern Apennine Peninsula (Magri et al. 2017).

Contrary to pollen records, fossils considered as macroremains of the genus Pterocarya in Cenozoic of Europe were reported beginning from the late Paleogene, that is middle/late Oligocene (Kvacek and Teodoridis 2007; Mai 1995). Earlier record of macrofossils of the wingnut (mainly leaflets) is rather doubtful and needs revision. In the late Oligocene, both leaflets and fruits of Pterocarya were rather rare in Europe. Neogene is the period when Pterocarya became the widespread and common component of the wetland communities of whole of Europe (Kovar-Eder 2003; Mai 1995; Zastawniak et al. 1996). Beginning from the early Miocene, remains of wingnut leaflets and fruits were reported in fossil plant assemblages from Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain and Ukraine. Similarly as in Miocene, in the Pliocene of Europe, macroremains of Pterocarya were also common component of wetland plant assemblages found in Bulgaria, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Poland, and Italy.

Due to significant cooling of the climate of Europe at the end of Pliocene, Pterocarya disappeared from the most area of Europe in the beginning of Pleistocene. In the early Pleistocene, however, macroremains of wingnut were still being found in some localities of western Europe, e.g. Maalbeek in the Netherlands, Alsace in Germany, through England, up to southern Europe in Italy, Spain and France (Magri et al. 2017; Martinetto 2015; Westerhoff 1998). In Italy, the fossil records of Pterocarya fruits are rather dense at the beginning of early Pleistocene, afterwards there is a surprising lack in the Calabrian, when Pterocarya is documented only by one endocarp in the earliest Calabrian site Santerno-Codrignano and by scanty leaflets of Pterocarya at the Oriolo site (Martinetto 2015). Middle Pleistocene record of wingnut macroremains comes from localities of Nowiny Zukowskie, Poland (fruit; Hrynowiecka and Szymczyk 2011) and Riano, Italy (fruits and leaflets; Follieri 1958).

The lack of P. fraxinifolia fossil data from Europe after 400–500 ka BP, even in the southernmost parts of the continent recognized as refugial areas of the Tertiary floras (Medail and Diadema 2009), could be interpreted as their very restricted abilities for migration, which was commented earlier.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, YG., Walas, Ł., Pietras, M. et al. Past, present and future suitable areas for the relict tree Pterocarya fraxinifolia (Juglandaceae): Integrating fossil records, niche modeling, and phylogeography for conservation. Eur J Forest Res 140, 1323–1339 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-021-01397-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-021-01397-6