Abstract

Brown rats are a prolific synanthropic pest species, but attempts to control their populations have had limited success. Rat population dynamics, dispersal patterns, and resistance to rodenticides are important parameters to consider when planning a control programme. We used population genetics and genotyping to investigate how these parameters vary in contrasting landscapes, namely one urban and two rural municipalities from eastern France. A total of 355 wild brown rats from 5 to 6 sites per municipality were genotyped for 13 microsatellite loci and tested for mutations in the Vkorc1 gene which confers resistance to some rodenticides. Results revealed a strong genetic structure of the sampled rat populations at both regional (between municipalities) and local (between sites within municipalities) levels. A pattern of isolation by distance was detected in the urban habitat and in one of the rural municipalities. GeneClass and DAPC analyses identified 25 (7%) and 36 (10%) migrants, respectively. Migrations occurred mostly between sites within each municipality. We deduced that rat dispersal is driven by both natural small-scale movements of individuals and longer-distance (human-assisted) movements. Mutation Y139F on gene Vkorc1 was significantly more prevalent in rural (frequency 0.26–0.96) than in urban sites (0.00–0.11), likely due to differences in selection pressures. Indeed, pest control is irregular and uncoordinated in rural areas, whereas it is better structured and strategically organised in cities. We conclude that simultaneous pest control actions between nearby farms in rural habitats are highly recommended in order to increase rat control success while limiting the spread of resistance to rodenticides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Key message

-

We compared the genetic structure, population connectivity, and frequency of anticoagulant resistance (mutation in the Vkorc1 gene) in rat populations from rural and urban municipalities in eastern France.

-

Rat populations revealed a strong genetic structure although small and long-distance dispersals were evidenced.

-

Frequency of mutation Y139F was significantly higher in rural habitats.

-

In order to limit the frequency of resistance to rodenticides in rural areas, our results suggest that control programmes should be coordinated between neighbouring farms within each municipality.

Introduction

The brown rat, Rattus norvegicus (Berkenhout, 1769), is one of the most important and common pest species worldwide. It has significant adverse effects on agricultural productivity, ecosystems (i.e. on native species and habitats), and public health (Capizzi et al. 2014). Rat control is extremely costly, and since the 1950s, it has mostly relied on the use of antivitamin K (AVK) rodenticides, i.e. anticoagulants (Hayes and Gaines 1950). Anticoagulant rodenticides target the vitamin K epoxide reductase (VKOR) enzyme, preventing the production of functional clotting factors, thus inhibiting coagulation (Tie and Stafford 2008). Because anticoagulants are relatively safe for humans (an antidote, vitamin K1, exists) and are easy to use, rodents were largely managed through chemical intervention, with much less emphasis on mechanical and environmental measures. In 1958, however, it was discovered that brown rats were becoming resistant to first-generation anticoagulant rodenticides (FGARs) (Boyle 1960). Therefore, more potent second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides (SGARs) (e.g. bromadiolone, difenacoum, flocoumafen, difethialone, and brodifacoum) were developed in the 1970s/1980s. Nevertheless, both primary and secondary poisoning of non-target species (due to increased persistence of these more effective compounds within the body) were described (Hughes et al. 2013; Langford et al. 2013) as well as possible evidence of rodent resistance (Prescott et al. 2011).

Resistance to antivitamin K rodenticides is attributed to single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the vitamin K epoxide reductase complex subunit 1 (Vkorc1) gene (Pelz et al. 2005; Rost et al. 2004). In France, the Y139F mutation (tyrosine to phenylalanine amino acid at VKORC1 position 139) is the most widely distributed resistance allele in brown rat populations (Grandemange et al. 2010). The prevalence of resistance alleles in rodent populations is likely due to selection pressure caused by the intensity and frequency of anticoagulant use in rat control programmes (Bishop et al. 1977; Greaves et al. 1977), while mutant alleles are most probably spread by natural movements of rats and by anthropogenic displacement of individuals via terrestrial or shipping routes (Pelz et al. 2005). Genetic resistance and ecological considerations, combined with the paucity of alternative methods to control rodent populations, highlight the need for a better understanding of the interplay between rat population dynamics, rat dispersal, and the distribution patterns of resistance to AVKs.

Population genetics has become a well-established tool to infer population dynamics, gene flow, and movement pathways (Abdelkrim et al. 2005; Piertney et al. 2016; Richardson et al. 2017). In this study, we investigated how these parameters vary in different landscape contexts, namely one urban and two rural municipalities from eastern France. We also examined the distribution of Vkorc1 variants within the sampled populations. Our results highlight the importance of upstream genetic investigation in the planning of rat control programmes. Finally, we present our recommendations for improving the rat population management scheme of the studied region and more generally, we highlight some sociological and scientific limitations which could be better addressed in future rat control campaigns and associated research.

Materials and methods

Study sites and sampling

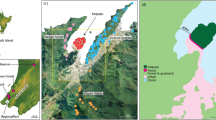

Trapping was conducted in two rural municipalities, Givors (GIV) and Saint-Romain-de-Popey (ROM), and one urban agglomeration, the city of Lyon (LYO), in eastern France (Fig. 1a). Pairwise distances (calculated using the fossil R package) between LYO, GIV, and ROM ranged from 18 to 34 km. Six sites (i.e. farms) per rural municipality (GIV1 to GIV6 and ROM1 to ROM6), selected on the basis of owner agreement and rat sighting reports, were investigated, while five urban sites in the city of Lyon (LYO1 to LYO5) were sampled. Animal trapping was conducted between 04/01/2010 and 28/03/2012.

Results of discriminant analysis of principal components of 355 brown rat genotypes collected in 17 different sites in the region of Lyon, eastern France. a Geographic location of the three studied municipalities in France. b Scatterplot of the genetic structure of the 355 sampled animals using 13 microsatellites, showing the individuals (points) and clusters (ellipses) in the first two axes of the DAPC space (horizontal: axis 1, vertical: axis 2). c Individual membership assignment of the 355 sampled animals to the genetic clusters identified by DAPC using 13 microsatellite loci. Individuals are represented by vertical bars, colours correspond to different genetic clusters, and each individual’s colour proportion indicates its membership to the corresponding cluster

Rats were trapped alive using Manufrance© live-traps (280 × 100 × 100 mm) baited with a mixture of peanut butter, oat flakes, and sardine oil. Traps were set at dusk and retrieved at dawn. Rats were euthanized by cervical dislocation, weighed, sexed, and a toe was collected and stored in individual tubes with 100% alcohol for subsequent DNA extraction. Body mass was used as a proxy for age (McGuire et al. 2006).

Animals were treated in accordance with European regulations and legislation governing the care and use of animals in research (Directive 86/609/EEC) (European Parliament 2010). The CBGP laboratory received approval (No. B34-169-003) from the Departmental Direction of Population Protection (DDPP, Hérault, France) for the sampling of rodents and the storage and use of their tissues. None of the species investigated in this study have protected status.

DNA extraction

Genomic DNA was extracted from toe samples using silica columns (Bio Basic Kit Inc, New York, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. DNA samples were stored at − 20 °C.

Microsatellite typing

We selected 13 unlinked (i.e. located on different chromosomes) microsatellite loci from the Rat Genome Database (http://rgd.mcw.edu/) (Table S1). Two further microsatellite loci, hereafter named Vka and Vkc (Table S1), were chosen for their physical proximity (9000 and 41,000 base pairs, respectively) to the locus Vkorc1. Because Vka and Vkc loci are physically linked to Vkorc1, they were expected to provide information on Y139F mutation flow between studied sites.

Microsatellite amplifications were performed in a 10 µl reaction volume containing 1 µl DNA, 5 µl 2X Qiagen Multiplex PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and 0.2 or 0.4 µM of each primer (Table S1). The microsatellite cycling protocol was: 95 °C for 15 min followed by 40 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 57 °C for 90 s, 72 °C for 60 s, and a final extension step of 60 °C for 10 min. Genotyping was carried out using an ABI3130 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, USA). Alleles were scored using GeneMapper™ software (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, USA). Fifteen per cent of the samples, chosen randomly, were genotyped twice, and repeatability was 100% for all loci.

Vkorc1 genotyping and sequencing

DNA samples were screened for the Y139F mutation using an allele-specific qPCR. A 91 base pair-segment was amplified using an Mx3000P qPCR System (Stratagene, Agilent Technologies, Massy, France). The reverse primer (5′-TCAGGGCTTTTTGACCTTGTG-3′) matched both the non-mutated Vkorc1 sequence and the Y139F mutated allele, whereas we used either a forward primer (Fwt) specific for the non-mutated wild-type Vkorc1 sequence (5′-CATTGTTTGCATCACCACCTA-3′) or a primer (F139F) specific for the Y139F mutated allele (5′-CATTGTTTGCATCACCACCTT-3′). Y139F genotyping could not be performed in 14 rats (GIV1 n = 1, GIV3 n = 4, GIV5 n = 1, GIV6 n = 2, ROM1 n = 2, ROM3 n = 1, ROM4 n = 1, ROM5 n = 2), leaving a genotyped sample size of 341.

To determine whether other Vkorc1 mutations existed in Y139F PCR-negative samples, Vkorc1 exons 1, 2, and 3 were PCR amplified as previously described (Grandemange et al. 2010), and then sequenced (Biofidal, France).

Statistical analysis

General statistics and mapping

The proportion test was used to compare allelic frequencies between urban and rural landscape. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare Ar, Ho, He, and distance of migration between urban and rural habitat. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was also used to compare FST statistics between population pairs located within a municipality (FSTintra) and population pairs from different municipalities (FSTextra). Statistical analyses were performed using R v.3.2.2 (R Development Core Team 2015), and the level of significance was set to 0.05. Base maps “BD ORTHO® 5 m”, freely available on the website of the National Institute of Geographic and Forestry Information (IGN, http://professionnels.ign.fr/bdortho-5m#tab-3), were used in QGIS v.2.16.2 (QGIS Development Team 2016).

Genetic diversity

At each site we calculated the frequency of the Y139F mutation. At each site the observed (Ho) and expected (He) heterozygosities were calculated at loci Vkorc1, Vka, Vkc, and for the 13 microsatellite loci, using unbiased estimates (Nei 1978) implemented in Genetix v.4.05 (Belkhir et al. 2004). Allelic association patterns between the Y139F mutation and the two linked microsatellite markers, Vka and Vkc, were investigated by comparing resistant and susceptible homozygous genotypes. At each site, deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was tested for each investigated locus and the 13 microsatellite loci using the exact test procedure implemented in Genepop v.4.2 (Raymond and Rousset 1995). Linkage disequilibrium (LD) between pairs of loci was tested using the exact probability test implemented in Genepop v.4.2 (Raymond and Rousset 1995). Correction for multiple testing was performed using the false discovery rate (FDR) method (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995) implemented in R. Genetix v.4.05 (Belkhir et al. 2004) was used to assess and test the significance of the unbiased inbreeding coefficient (FIS) at each site, calculated according to Weir and Cockerham (1984). Significance of FIS per site was determined using 10,000 FIS bootstraps per population. Allelic richness (Ar) was estimated using the rarefaction procedure implemented in Fstat v.2.9.3.2 (Goudet 2001) for a minimum sample size of six individuals (Goudet 1995).

Micro-Checker v.2.2.3 (Van Oosterhout et al. 2004) was used to test for the possibility of scoring errors, allelic dropout, and null alleles.

Bottleneck v.1.2.02 (Cornuet and Luikart 1996; Piry et al. 1999) was used to determine whether the populations had undergone a recent bottleneck. A two-tailed Wilcoxon sign rank test was performed under a two-phase model. We constrained the model by defining 70% of mutations as conforming to a stepwise mutation model and 30% as multi-step model. Variance was set at 10% and number of replications at 10,000.

Spatial genetic structure and migration

Genetic differentiation between all sites was quantified with FST statistics computed in Genepop v.4.2 (Raymond and Rousset 1995; Weir and Cockerham 1984) using the pairwise distance matrix, and significance was tested using Fisher’s exact probability test. Within each municipality, isolation by distance (IBD) was tested using a Mantel test implemented in R (ade4 package) by regressing the pairwise estimates of FST/(1 − FST) against the logarithm of Euclidean geographical distances between sites (Rousset 1997).

First-generation migrants were detected in GeneClass v.2.0 (Piry et al. 2004) using a likelihood computation (Paetkau et al. 2004) with 10,000 simulated genotypes and the Lh statistics (i.e. the likelihood of finding an individual in a given population in which it was sampled), as recommended when all source populations have not been sampled. Only individuals with a probability < 0.01 were considered as putative migrants (Paetkau et al. 2004).

Genetic structure within and genetic differentiation between sites and municipalities was investigated using discriminant analysis of principal components (DAPC) (Jombart et al. 2010) in the adegenet package (Jombart 2008) implemented in R. DAPC does not require the assumption of HWE, so all unlinked microsatellite loci were included in this analysis. For each analysis, the optimal number of clusters was determined using k-means clustering, run sequentially with increasing values of k, and the different clustering results were compared using Bayesian information criterion (BIC) (Jombart et al. 2010). For each migrant, the distance between sampling and assignment sites was calculated using the fossil R package.

To evaluate the power of the marker set for individual identification, the unbiased probability of identity (PIDunbiaised) (i.e. PID corrected for small sample size) and PID for siblings (PIDsib) (i.e. PID among a population of siblings) were calculated using Gimlet v.1.3.3. (Nathaniel 2002). PID was calculated for each microsatellite locus and then multiplied across loci to give the overall PID (Waits et al. 2001). We sought PIDunbiaised and PIDsib values < 0.001 (Waits et al. 2001).

Results

Genetic diversity

A total of 355 brown rats were trapped (Table S2). The number of alleles at each microsatellite locus ranged from 5 to 17 (Table S3). Calculated at each site, Ar, computed for a minimum sample size of six individuals, ranged between 3.36 and 3.94 in GIV, 3.11–4.11 in ROM, and 3.12–3.82 in LYO (Table 1). There was no statistical difference in Ar between urban (Lyon city) and rural (GIV and ROM) sites (Wilcoxon W = 33.5, p = 0.75).

After FDR correction, 61/1326 (4.6%) pairs of neutral microsatellite combinations had significant LD (p < 0.05). These significant associations did not systematically affect the same pairs of loci in each site. Therefore, we concluded that the 13 microsatellite loci used were independent, which is consistent with their physical location on the rat chromosomal map. Results from LD tests are shown in Fig. S1.

Micro-Checker did not detect evidence for scoring errors due to stuttering, neither for large allele dropout, nor for a high frequency of null alleles in any of the tested loci (van Oosterhout values are given in Table S3).

Three sites in GIV (GIV3, GIV4, GIV6), four in ROM (ROM1, ROM3, ROM5, ROM6), and two in LYO (LYO2, LYO4) showed significant deviation from HWE (Table 1). HWE deviation was associated with heterozygote deficiency at GIV6, ROM1, and LYO2 (FIS = 0.024, 0.118, and 0.014, respectively), whereas for the other sites the deviation was associated with heterozygote excess (FIS = −0.017 to − 0.180).

In rural habitat, Ho across the 13 loci ranged from 0.49 (ROM2) to 0.77 (GIV5) and He ranged from 0.55 (ROM4) to 0.68 (GIV2 and ROM1). In Lyon, Ho across the 13 loci ranged from 0.56 to 0.77 and He from 0.56 to 0.66 (Table 1). No statistical differences in Ho (W = 30.5, p = 1) and He (W = 38, p = 0.43) were observed between rural and urban populations.

Under the two-phase model, the results displayed a bottleneck signature for the populations in GIV1, GIV5, and LYO4 (Table 1).

Spatial genetic structure and migration

Pairwise FSTintra estimates (between population pairs within each municipality) ranged from 0.095 to 0.217 in GIV, from 0.077 to 0.268 in ROM, and from 0.033 to 0.232 in LYO (Table 2). A significant IBD pattern was observed in GIV (Mantel r = 0.54, p = 0.03) and LYO (Mantel r = 0.87, p = 0.04), but not in ROM (Mantel r = 0.37, p = 0.20) (Fig. S2). Pairwise FSTextra estimates (between population pairs located in different municipalities) ranged from 0.127 to 0.355 (Table 2). Pairwise FSTintra estimates were significantly smaller than pairwise FSTextra estimates (W = 442, p < 0.001) (Fig. S3).

PIDunbiaised and PIDsib were 9.64e−15 and 5.46e−06, respectively (Table S3).

The DAPC run on all sampled individuals (355) assigned most individuals to their municipality of capture (Fig. 1b and 1c). However, two clusters from LYO largely overlapped with ROM clusters, indicating potential gene flow between LYO and ROM (Fig. 1b). ROM and GIV clusters were highly differentiated by DAPC although two individuals from ROM were assigned to a GIV cluster (green bars in ROM, Fig. 1c) and one individual from GIV was assigned to a ROM cluster (orange bar in GIV, Fig. 1c).

The most likely number of genetic clusters, as determined by DAPC performed on each municipality, was five in GIV (Fig. 2e), seven in ROM (Fig. 3e), and four in LYO (Fig. 4e). Cluster 3 in ROM included only two individuals while cluster 5 consisted of one animal (Fig. 3e). These three animals could not be assigned to any of the sampled populations in ROM but two were assigned to GIV and one to LYO in the global DAPC (Fig. 1c). Similarly, cluster 1 in LYO was composed of two individuals (Fig. 4e) which were assigned to ROM in the global DAPC (orange bars in LYO, Fig. 1c). Interestingly, these two individuals, detected as first-generation migrants (LYO829 and LYO830, Table 3), were also the only two individuals from LYO with the Y139F mutation. Rat populations were highly structured in GIV (Fig. 2d and 2e). In contrast, DAPC analysis highlighted potential gene flow between ROM1, ROM2, ROM3, and ROM6 (Fig. 3d, e) and substantial gene flow was also detected between LYO1, LYO2, and LYO3 (Fig. 4d, e).

Results of the genetic analyses of 170 brown rat genotypes collected in the rural municipality of Givors (GIV), eastern France. a Sampling sites in Givors. Map data: BD ORTHO® 5 m, National Institute of Geographic and Forestry Information (IGN). b Individual Vkorc1 genotypes determining resistance to AVK rodenticides. Dark blue: resistant homozygote Y139F/Y139F (mutated on both alleles), cyan: resistant heterozygote Y139F/−, light blue: susceptible −/− (wild type, non-mutated), white: data not available. c First-generation migrants detected with GeneClass (dark grey bars). d Individual membership assignment of rats to the genetic clusters identified by DAPC conducted on animals sampled in GIV using data from 13 microsatellite loci. Individuals are represented by vertical bars, colours correspond to different genetic clusters, and each individual’s colour proportion indicates its membership to the corresponding cluster. e Scatterplot of the genetic structure in GIV using 13 microsatellite loci, showing the individuals (points) and clusters (ellipses) in the first two axes of the DAPC space (horizontal: axis 1, vertical: axis 2). For b–d sampling site for each individual is indicated at the bottom

Results of the genetic analyses of 118 brown rat genotypes collected in the rural municipality of Saint-Romain-de-Popey (ROM), eastern France. a Sampling sites in Saint-Romain-de-Popey. Map data: BD ORTHO® 5 m, National Institute of Geographic and Forestry Information (IGN). b Individual Vkorc1 genotypes determining resistance to AVK rodenticides. Dark blue: resistant homozygote Y139F/Y139F (mutated on both alleles), cyan: resistant heterozygote Y139F/−, light blue: susceptible −/− (wild type, non-mutated), white: data not available. c First-generation migrants detected with GeneClass (dark grey bars). d Individual membership assignment of rats to the genetic clusters identified by DAPC conducted on animals sampled in ROM using data from 13 microsatellite loci. Individuals are represented by vertical bars, colours correspond to different genetic clusters, and each individual’s colour proportion indicates its membership to the corresponding cluster. e Scatterplot of the genetic structure in ROM using 13 microsatellite loci, showing the individuals (points) and clusters (ellipses) in the first two axes of the DAPC space (horizontal: axis 1, vertical: axis 2). For b–d sampling site for each individual is indicated at the bottom

Results of the genetic analyses of 67 brown rat genotypes collected in Lyon city (LYO), eastern France. a Sampling sites in Lyon. Map data: BD ORTHO® 5 m, National Institute of Geographic and Forestry Information (IGN). b Individual Vkorc1 genotypes determining resistance to AVK rodenticides. Dark blue: resistant homozygote Y139F/Y139F (mutated on both alleles), cyan: resistant heterozygote Y139F/−, light blue: susceptible −/− (wild type, non-mutated), white: data not available. c First-generation migrants detected with GeneClass (dark grey bars). d Individual membership assignment of rats to the genetic clusters identified by DAPC conducted on animals sampled in LYO using data from 13 microsatellite loci. Individuals are represented by vertical bars, colours correspond to different genetic clusters, and each individual’s colour proportion indicates its membership to the corresponding cluster. e Scatterplot of the genetic structure in LYO using 13 microsatellite loci, showing the individuals (points) and clusters (ellipses) in the first two axes of the DAPC space (horizontal: axis 1, vertical: axis 2). For b–d sampling site for each individual is indicated at the bottom

GeneClass and DAPC conducted on each site identified 25 (7%) and 36 (10%) migrants, respectively (20 migrants were identified by both methods) (Table 3). GeneClass evidenced 12/25 (48%) migrants as males (9/12 were adults) and 12 as females (7 adults, 1 NA data on sex) while 10/25 (40%) presented genotype Y139F/Y139F at locus Vkorc1 (homozygote resistant to AVKs) and 7 (28%) presented the wild genotype (homozygote susceptible −/−). DAPC evidenced 19/36 (53%) migrants as males (13/19 were adults) and 12 (33%) as females (8 adults, 5 NA data on sex) while 13/36 (52%) presented genotype Y139F/Y139F at locus Vkorc1 and 9 (36%) presented the wild genotype (Table 3, Figs. 2b, c, 3b, c, 4b, c).

Based on DAPC results, median distance between sampling and assignment sites did not statistically differ between rats sampled in Lyon city (3.6 km) and individuals captured in rural habitats (2.0 km) (W = 84, p = 0.08). Five individuals were unlikely to originate from any of the sampled sites.

Genetic resistance to rodenticides

The Y139F mutation was present in all rural sites, with allelic frequency varying between 0.26 and 0.96 (Table 1). In Lyon, Y139F was found in one single site (LYO1) with frequency 0.11 (two homozygous individuals Y139F/Y139F). Y139F frequencies were significantly different in rural versus urban habitat (p < 0.01). The proportion of individuals carrying the homozygous Y139F/Y139F genotype varied, depending on the site, between 0 (LYO2, LYO3, LYO4, LYO5) and 0.92 (ROM5); the proportion of heterozygous Y139F/− individuals varied from 0 (ROM2, LYO1, LYO2, LYO3, LYO4, LYO5) to 0.61 (ROM6), while the proportion of individuals with the non-mutated (−/−, wild type) genotype ranged between 0 (GIV1, GIV3, ROM3) and 1 (LYO2, LYO3, LYO4, LYO5) (Table 1). No other mutations were detected in Vkorc1 following sequencing. HWE deviations at locus Vkorc1 occurred in ROM1 (p = 0.025) and LYO1 (p = 0.003) (Table 1).

The number of alleles at loci Vka and Vkc was 10 and 8, respectively (Table S1), while per site it ranged from 2 to 6 and from 2 to 4, respectively. Corrected allelic richness (Ar), computed for a minimum sample size of six individuals, ranged between 1.15 and 4.13 for Vka and 0.00–3.57 for Vkc (Table 1). Locus Vka demonstrated HWE deviations in ROM1 (p = 0.019) and LYO1 (p = 0.01). All populations were in HWE for locus Vkc. Mutation Y139F was almost exclusively associated with allele 328 at locus Vka (99.5% of the haplotypes) and with allele 327 at locus Vkc (98.3%) (Fig. S4). Linkage disequilibrium was examined at the 13 sites where Y139F was present. Significant LD (p < 0.05) both between Y139F and Vka, and between Y139F and Vkc, was found at nine sites. Significant LD reflected the physical proximity between loci Vkorc1 and Vka/Vkc on chromosome 1. However, in GIV5 and ROM2 no LD was observed between Y139F and Vka or Vkc, perhaps due to weak statistical power caused by low sample sizes (N = 6 at both sites). No LD was detected at ROM5 despite a large sample size (N = 40).

Discussion

Rat population dynamics and dispersal

Because urban habitats present several physical barriers to rat movements, urban rat populations are expected to be more fragmented than in rural landscapes (Combs et al. 2018b; Gardner-Santana et al. 2009; Kajdacsi et al. 2013). On the contrary, we showed that, as in urban habitats, rural rat colonies present low gene flow between populations from nearby farms. In particular, the demographically meaningful genetic parameters we tested were not significantly different between rural and urban populations. Genetic diversity, estimated by He, averaged 0.61 in farms and 0.60 in urban sites, which is close to values reported from urban rat populations investigated near Paris, France (He = 0.63) (Desvars-Larrive et al. 2017), in Salvador, Brazil (mean He = 0.66) (Kajdacsi et al. 2013), and in Baltimore, USA (mean He = 0.73) (Gardner-Santana et al. 2009). The mean genetic differentiation between rat populations within the three investigated municipalities, measured by mean FSTintra, was 0.15, a value close to those reported in Salvador (mean FST = 0.17) (Kajdacsi et al. 2013) and Baltimore (mean FST = 0.10) (Gardner-Santana et al. 2009). In comparison, the mean genetic differentiation between rat populations located in different municipalities (FSTextra) was 0.23. These results are indicative of a low gene flow between sites within each municipality and quasi null exchanges among municipalities, and therefore suggest a low level of effective dispersal (dispersal followed by reproduction in the new location) and a strong isolation of the populations. The presence of physical barriers between the investigated municipalities (e.g. major waterways and roads, valleys) can explain the intra-municipal isolation of the rat populations in GIV, ROM, and LYO (Combs et al. 2018a; Richardson et al. 2017).

Effective dispersal between adjacent populations is expected to induce a stepping-stone pattern of IBD (Gardner-Santana et al. 2009; Kimura and Weiss 1964). Our results are unclear on this; the pattern of IBD was verified in GIV and LYO, although only on the outer margin of significance, but not in ROM. Absence of correlation between genetic diversity and geographical distances is expected when effective dispersal is a rare event and/or when passive (human-assisted) dispersal occurs, for example, when the intensity of connections between different locations is not correlated to inter-location distance but to anthropogenic parameters, such as frequency of social or commercial exchanges (Fountain et al. 2014; Holland and Cowie 2007). We surmise that intrinsic differences in habitat traits (e.g. in resource abundance and quality, number of harbourages, and rat control actions) can impact connectivity and gene flow between neighbouring populations, leading to deviations from IBD and genetic structuring at small spatial scales. In line with this hypothesis, we detected large variations in the genetic diversity of the investigated rat populations (He = 0.49–0.77), a finding consistent with similar studies in Baltimore (0.57–0.84) (Gardner-Santana et al. 2009) and Salvador, Brazil (0.57–0.72) (Kajdacsi et al. 2013).

As we could not investigate all rat populations within the three surveyed municipalities, it is difficult to give a precise estimate of dispersal distances. However, several movements between farms or between urban sites located a few kilometres apart were detected (one-fourth of migrants were assigned to locations > 2.5 km). Such instances of long-distance dispersal, albeit infrequent, have been described in other genetic studies on urban brown rats (Gardner-Santana et al. 2009; Glass et al. 2016; Heiberg et al. 2012; Richardson et al. 2017). In Combs et al. (2018b), several rats were assigned to areas between 2 and 11.5 km apart. Long-distance movements were also suspected for five rats in our study, although none of them could be assigned to any identified genetic clusters.

We observed a small but consistent percentage of first-generation migrants across rural and urban sites. Seven and ten per cent of migrants were detected using GeneClass and DAPC, respectively, percentages relatively close to those reported in Baltimore (6.5%) (Gardner-Santana et al. 2009) and Salvador (6.8%) (Kajdacsi et al. 2013). Moreover, our results strongly suggest that not only males migrate (Calhoun 1963; Kajdacsi et al. 2013) but also females (33–48% of migrants were females). These results are consistent with the study of Gardner-Santana et al. (2009) who did not see sex-biased dispersal in urban brown rats. Although their study identified only mature adults as first-generation migrants, our results showed that a third of the identified migrants was composed of young animals and subadults. It is unclear whether rats are capable of mating after dispersal (attacks from socially dominant males towards new males have been described) (Blanchard and Blanchard 1977; Calhoun 1963; Davis and Christian 1956), but our data presume that female and young rats may contribute considerably to gene flow.

Significant deviation from HWE was observed in more than half of our investigated sites. HWE deviation is indicative of a limited population size where a reduced number of males produce descendants and/or of a recent admixture of two or more populations or families (Berdoy et al. 1995). Indeed, in brown rat colonies, dominant males tend to monopolise females and have privileged access to reproduction (Calhoun 1963). Also, population recovery after a control event might result from both the recovery of local survivors and the colonisation by migrants from the nearby areas.

Another future study could use slower-evolving markers (e.g. cytochrome oxidase gene I) to enlighten global brown rat phylogeographic patterns in eastern France, but also over the whole country. Elucidating global routes of brown rat expansion, genomic contribution of the first migrants within invaded areas, urban/rural population differentiation, and global population structure will allow for a better design of rat control efforts.

Resistance to rodenticides and rat control strategy

Although more than one mutated allele of the Vkorc1 gene can coexist within a region (Grandemange et al. 2010) and also within the same population (Pelz et al. 2005), our results clearly established the presence of one single mutation (Y139F) in the investigated region. The Y139F mutation was almost exclusively associated with allele 328 at locus Vka and allele 327 at locus Vkc which demonstrates that Y139F was introduced, together with the haplotype allele 328 at locus Vka and allele 327 at locus Vkc, to the region of Lyon via a single introduction event or via recurrent introductions from the same source. The low genetic diversity at nearby loci suggests that the introduction of the Y139F mutation to this part of France was recent (Barton 2000) and was most likely followed by a wide geographical dispersal of Y139F across the region.

Mutation Y139F was highly prevalent in the two rural municipalities, while it was almost absent in Lyon city. Disparities in the prevalence of the mutation Y139F could derive from differences in rat control practices. Pest control in Lyon city involves the Department of Urban Ecology, which mainly uses bromadiolone and difenacoum in the public urban green spaces and buildings, while pest management professionals are in charge of the sewer system (where difenacoum is mostly used) and private buildings. Rat control measures are administered at the macro-city scale and follow a strict protocol, with concerted rotation of the molecules and fixed bait stations. Therefore, urban rats undergo a continuous and strong selection pressure that keeps resistance alleles at a low prevalence in the rat populations. In contrast, pest control in rural areas is handled at the farm level, by the farmers themselves. It involves mostly the use of bromadiolone outdoor and FGARs indoor, typically without rotation of the compounds, and at a frequency mostly depending on rat (or rat signs) sightings and economic considerations. This type of management creates a fluctuating selection pressure that helps to promote the selection of alleles which confer resistance to some rodenticides (Bishop et al. 1977; Grandemange et al. 2009; Pelz et al. 2005). In our study, 78% of the migrants carried one or two Y139F mutated alleles. In spite of intense aggression reported towards migrants (Blanchard and Blanchard 1977; Calhoun 1963) resistance to rodenticides is probably advantageous for migrants to establish locally during a rat control event. A fine-scale longitudinal monitoring programme of rat population recovery after control events is needed to understand the underlying ecological processes.

Implications for rat control programmes

The presence of rat populations resistant to FGARs often encourages the use of more potent, and more ecotoxic, SGARs, presenting higher risks of secondary poisoning and environmental contamination. There is little published evidence, however, about the practical effectiveness of anticoagulants against Y139F-mutated rats. Grandemange et al. (2009) recommended not using FGARs and bromadiolone when this mutation is present. They suggested that difenacoum might be efficient, although its use could increase the frequency of the resistance mutation. Highly potent compounds, such as difethialone (and by extrapolation presumably brodifacoum and flocoumafen), may also be effective (Grandemange et al. 2009).

Information campaigns for an educated and safe use of rodenticides, combined with technical and possibly financial support, will be essential to change rodent control practices in rural habitats. Resistance is likely to spread locally, either by natural dispersal or through human transport. Within the investigated region in eastern France, attempts to eradicate rat populations at the local scale of an urban patch or a farm are most likely doomed to fail because interconnectivity with neighbouring populations is quite common. In the rural municipalities, a coordinated pest control strategy employed by several neighbouring farms would likely yield the most immediate positive impact and thus be the best strategy to consider. Non-chemical control methods must also be developed through integrated pest management programmes, involving both environmental (habitat modification, sanitation, harbourage reduction, rat-proofing) and mechanical (trapping) measures (Meerburg et al. 2004; Mughini Gras et al. 2012).

Limitations of the study

Studies that compare population characteristics (e.g. pathogen prevalence, population genetics, genotyping diversity) in urban versus other habitat types, without considering any detailed environmental parameters or meaningful features, do not allow understanding the specific habitat characteristics that may effectively contribute to the observed differences (Rothenburger et al. 2017). Nevertheless, they can highlight a trend. Further investigations, taking into account micro-environmental and societal parameters (e.g. farmers´ practices), are needed to highlight fine-scale environmental specificities that could explain the observed differences. For example, a landscape genetics study along presumed pathways across the rural–urban gradient may help to identify genetic units, mode of migration, and corridors, providing critical information for rat population management.

Sociological data are missing to support our different hypotheses. No data are available on truck movements within and between rural municipalities, neither on the intensity of connections between Lyon city and the surrounding municipalities. Detailed data about the use of anticoagulants in the field were not available and constitute the major limitations of this study. Most of the interviewed farmers did not wish to answer our questions regarding their practices, whereas in the city, the number of rodenticide users is high and pest management professionals were difficult to contact, which rendered the collection of precise data infeasible.

Conclusion

This research provides the first comparative genetic study on rural and urban rat populations and produces substantial advances on the understanding of rat population dynamics and dispersal in these two contrasting landscapes. Our results highlight the interest of population genetics and genotyping as tools for determining the most appropriate spatial scale for rat control measures. Overall, our study calls for greater coordination of rat management between neighbouring farms in order to limit the frequency and spread of anticoagulant resistance. We feel that we must now bridge the gap between rodenticide users and researchers. In a mutually beneficial collaboration, rodenticide users would supply ground data (about rodenticide use and rodent observations) while researchers would share results which could provide support to implement best-practice guidelines for a responsible use of rodenticides.

Author contributions

JFC, EB, PB designed the research, obtained funding, and conducted the field work. AHa, AHo, PB, EB, VL contributed reagents and analytical tools. ADL and JFC performed the data curation, analysis, and visualisation. ADL and JFC wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

References

Abdelkrim J, Pascal M, Calmet C, Samadi S (2005) Importance of assessing population genetic structure before eradication of invasive species: examples from insular Norway rat populations. Conserv Biol 19:1509–1518

Barton NH (2000) Genetic hitchhiking. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 355:1553–1562

Belkhir K, Borsa P, Chikhi L, Raufaste N, Bonhomme F (2004) GENETIX 4.05, Windows TM software for population genetics. Laboratoire génome, populations, interactions, CNRS UMR 5000

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Methodol 57:289–300

Berdoy M, Smith P, Macdonald DW (1995) Stability of social status in wild rats: age and the role of settled dominance. Behaviour 132:193–212

Bishop JA, Hartley DJ, Partridge GG (1977) The population dynamics of genetically determined resistance to warfarin in Rattus norvegicus from mid Wales. Heredity 39:389–398

Blanchard RJ, Blanchard CB (1977) Aggressive behavior in the rat. Behav Biol 21:197–224

Boyle CM (1960) Case of apparent resistance of Rattus norvegicus Berkenhout to anticoagulant poisons. Nature 188:517

Calhoun JB (1963) The ecology and sociology of the Norway rat. U.S. Deptartment of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Bethesda, Maryland

Capizzi D, Bertolino S, Mortelliti A (2014) Rating the rat: global patterns and research priorities in impacts and management of rodent pests. Mammal Rev 44:148–162

Combs M, Byers KA, Ghersi BM, Blum MJ, Caccone A, Costa F, Himsworth CG, Richardson JL, Munshi-South J (2018a) Urban rat races: spatial population genomics of brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) compared across multiple cities. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 285:20180245

Combs M, Puckett EE, Richardson J, Mims D, Munshi-South J (2018b) Spatial population genomics of the brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) in New York City. Mol Ecol 27:83–98

Cornuet JM, Luikart G (1996) Description and power analysis of two tests for detecting recent population bottlenecks from allele frequency data. Genetics 144:2001–2014

Davis DE, Christian JJ (1956) Changes in Norway rat populations induced by introduction of rats. J Wildl Manag 20:378–383

Desvars-Larrive A, Pascal M, Gasqui P, Cosson J-F, Benoît E, Lattard V, Crespin L, Lorvelec O, Pisanu B, Teynié A, Vayssier-Taussat M, Bonnet S, Marianneau P, Lacôte S, Bourhy P, Berny P, Pavio N, Le Poder S, Gilot-Fromont E, Jourdain E, Hammed A, Fourel I, Chikh F, Vourc’h G (2017) Population genetics, community of parasites, and resistance to rodenticides in an urban brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) population. PLoS ONE 12:e0184015

European Parliament (2010) Directive 2010/63/EU of the European parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes

Fountain T, Duvaux L, Horsburgh G, Reinhardt K, Butlin RK (2014) Human-facilitated metapopulation dynamics in an emerging pest species, Cimex lectularius. Mol Ecol 23:1071–1084

Gardner-Santana LC, Norris DE, Fornadel CM, Hinson ER, Klein SL, Glass GE (2009) Commensal ecology, urban landscapes, and their influence on the genetic characteristics of city-dwelling Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus). Mol Ecol 18:2766–2778

Glass GE, Klein SL, Norris DE, Gardner LC (2016) Multiple paternity in urban Norway rats: extended ranging for mates. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 16:342

Goudet J (1995) FSTAT (Version 1.2): a computer program to calculate F-statistics. J Hered 86:485–486

Goudet J (2001) FSTAT, a program to estimate and test gene diversities and fixation indices v.2.9.3. Lausanne University, Lausanne, Switzerland. https://www2.unil.ch/popgen/softwares/fstat.htm

Grandemange A, Kohn MH, Lasseur R, Longin-Sauvageon C, Berny P, Benoit E (2009) Consequences of the Y139F Vkorc1 mutation on resistance to AVKs: in vivo investigation in a 7th generation of congenic Y139F strain of rats. Pharmacogen Genom 19:742–750

Grandemange A, Lasseur R, Longin-Sauvageon C, Benoit E, Berny P (2010) Distribution of VKORC1 single nucleotide polymorphism in wild Rattus norvegicus in France. Pest Manag Sci 66:270–276

Greaves JH, Redfern R, Ayres PB, Gill JE (1977) Warfarin resistance: a balanced polymorphism in the Norway rat. Genet Res 30:257–263

Hayes WJ, Gaines TB (1950) Control of Norway rats with residual rodenticide warfarin. Public Health Rep 1896–1970(65):1537–1555

Heiberg A-C, Sluydts V, Leirs H (2012) Uncovering the secret lives of sewer rats (Rattus norvegicus): movements, distribution and population dynamics revealed by a capture–mark–recapture study. Wildl Res 39:202–219

Holland BS, Cowie RH (2007) A geographic mosaic of passive dispersal: population structure in the endemic Hawaiian amber snail Succinea caduca (Mighels, 1845). Mol Ecol 16:2422–2435

Hughes J, Sharp E, Taylor MJ, Melton L, Hartley G (2013) Monitoring agricultural rodenticide use and secondary exposure of raptors in Scotland. Ecotoxicology 22:974–984

Jombart T (2008) adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24:1403–1405

Jombart T, Devillard S, Balloux F (2010) Discriminant analysis of principal components: a new method for the analysis of genetically structured populations. BMC Genet 11:94

Kajdacsi B, Costa F, Hyseni C, Porter F, Brown J, Rodrigues G, Farias H, Reis MG, Childs JE, Ko AI, Caccone A (2013) Urban population genetics of slum-dwelling rats (Rattus norvegicus) in Salvador. Brazil. Mol Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12455

Kimura M, Weiss GH (1964) The stepping stone model of population structure and the decrease of genetic correlation with distance. Genetics 49:561–576

Langford KH, Reid M, Thomas KV (2013) The occurrence of second generation anticoagulant rodenticides in non-target raptor species in Norway. Sci Total Environ 450–451:205–208

McGuire B, Pizzuto T, Bemis WE, Getz LL (2006) General ecology of a rural population of Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) based on intensive live trapping. Am Midl Nat 155:221–236

Meerburg BG, Bonde M, Brom FWA, Endepols S, Jensen AN, Leirs H, Lodal J, Singleton GR, Pelz HJ, Rodenburg TB, Kijlstra A (2004) Towards sustainable management of rodents in organic animal husbandry. NJAS Wagen J Life Sci 52:195–205

Mughini Gras L, Patergnani M, Farina M (2012) Poison-based commensal rodent control strategies in urban ecosystems: some evidence against sewer-baiting. EcoHealth 9:75–79

Nathaniel V (2002) GIMLET: a computer program for analysing genetic individual identification data. Mol Ecol Notes 2:377–379

Nei M (1978) Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics 89:583–590

Paetkau D, Slade R, Burden M, Estoup A (2004) Genetic assignment methods for the direct, real-time estimation of migration rate: a simulation-based exploration of accuracy and power. Mol Ecol 13:55–65

Pelz H-J, Rost S, Hünerberg M, Fregin A, Heiberg A-C, Baert K, MacNicoll AD, Prescott CV, Walker A-S, Oldenburg J, Müller CR (2005) The genetic basis of resistance to anticoagulants in rodents. Genetics 170:1839–1847

Piertney SB, Black A, Watt L, Christie D, Poncet S, Collins MA (2016) Resolving patterns of population genetic and phylogeographic structure to inform control and eradication initiatives for brown rats Rattus norvegicus on South Georgia. J Appl Ecol 53:332–339

Piry S, Luikart G, Cornuet JM (1999) Computer note. BOTTLENECK: a computer program for detecting recent reductions in the effective size using allele frequency data. J Hered 90:502–503

Piry S, Alapetite A, Cornuet J-M, Paetkau D, Baudouin L, Estoup A (2004) GENECLASS2: a software for genetic assignment and first-generation migrant detection. J Hered 95:536–539

Prescott CV, Buckle AP, Gibbings JG, Allan NW, Stuart AM (2011) Anticoagulant resistance in Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus Berk.) in Kent: a VKORC1 single nucleotide polymorphism, tyrosine139phenylalanine, new to the UK. Int J Pest Manage 57:61–65

QGIS Development Team (2016) QGIS geographic information system. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project v. 2.18.12. http://www.qgis.org/

R Development Core Team (2015) R: A language and environment for statistical computing v.3.2.2 R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org

Raymond M, Rousset F (1995) GENEPOP (Version 1.2): population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J Hered 86:248–249

Richardson JL, Burak MK, Hernandez C, Shirvell JM, Mariani C, Carvalho-Pereira TSA, Pertile AC, Panti-May JA, Pedra GG, Serrano S, Taylor J, Carvalho M, Rodrigues G, Costa F, Childs JE, Ko AI, Caccone A (2017) Using fine-scale spatial genetics of Norway rats to improve control efforts and reduce leptospirosis risk in urban slum environments. Evol Appl 10:323–337

Rost S, Fregin A, Ivaskevicius V, Conzelmann E, Hortnagel K, Pelz H-J, Lappegard K, Seifried E, Scharrer I, Tuddenham EGD, Muller CR, Strom TM, Oldenburg J (2004) Mutations in VKORC1 cause warfarin resistance and multiple coagulation factor deficiency type 2. Nature 427:537–541

Rothenburger JL, Himsworth CH, Nemeth NM, Pearl DL, Jardine CM (2017) Environmental factors and zoonotic pathogen ecology in urban exploiter species. EcoHealth. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-10017-11258-10395

Rousset F (1997) Genetic differentiation and estimation of gene flow from F-statistics under isolation by distance. Genetics 145:1219–1228

Tie JK, Stafford DW (2008) Structure and function of vitamin K epoxide reductase. Vitam Horm 78:103–130

Van Oosterhout C, Hutchinson WF, Wills DPM, Shipley P (2004) MICRO-CHECKER: software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol Ecol Notes 4:535–538

Waits LP, Luikart G, Taberlet P (2001) Estimating the probability of identity among genotypes in natural populations: cautions and guidelines. Mol Ecol 10:249–256

Weir BS, Cockerham CC (1984) Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution 38:1358–1370

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna. Data used in this work were partly produced by the technical facilities of the SFR119/Labex CeMEB. We thank Karine Berthier and Anne Loiseau for their help in the genotyping of microsatellites, and the farm owners and the municipality of Lyon, who have facilitated access to the rat colonies for the sampling. We acknowledge Rachel Peat and James Robins for language editing of the manuscript. Financial support was provided by Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA Grant) and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (RODENT programme, ANR-2009-CESA-008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by J. Jacob.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Desvars-Larrive, A., Hammed, A., Hodroge, A. et al. Population genetics and genotyping as tools for planning rat management programmes. J Pest Sci 92, 691–705 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-1043-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-018-1043-4