Abstract

This paper introduces a new derivatization agent for the simultaneous quantification of formaldehyde and methanol during curing reactions of complex organic coatings. Formaldehyde emitted from a polyester-melamine coating is derivatized in a gas phase reaction with unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH) to form formaldehyde dimethylhydrazone (FDMH). UDMH and FDMH tend to degrade at temperatures above 200 °C rather fast. The applicability of derivatization agent and analyte as well as their degradation products are therefore discussed thoroughly. In this method curing temperatures of 150 °C with incubation times between 0.1 and 60 min are used to trigger crosslinking reactions. The emissions of formaldehyde and methanol are continuously quantified with headspace gas chromatography to obtain an emission trend. While one of the main sources of formaldehyde is the demethylolation during crosslinking, methanol is produced via hexamethoxymethylmelamine (HMMM) deetherification and as a condensation byproduct. The emission monitoring shows a high potential for comparative and mechanistic investigations. Results show good repeatability with low standard deviations (< 7%) with a quantification limit of 2.09 µg for formaldehyde and 2.08 µg for methanol.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Polycondensates based on alkylated melamine–formaldehyde resins—in particular hexamethoxymethylmelamine (HMMM)—release methanol during crosslinking as a condensation byproduct [1]. According to the specific formulation of the coating and its corresponding process conditions formaldehyde may occur as a byproduct, which is known to be a toxic chemical. When exposed to methanol or formaldehyde side effects can range from mucous membrane irritation to acute toxicity concerns [2, 3]. Besides toxicity issues the amount of formaldehyde and methanol produced might give insights into enhanced curability of individual coatings [4]. To assess these emissions, adequate analytical methods are needed. Quantitative methods to analyze methanol via Headspace-GC–MS (HS-GC–MS) have already been developed for other applications like solid insulation systems [5]. Formaldehyde on the other hand is, mainly due to its polarity, lack of chemical standards, and its high reactivity, relatively difficult to quantify. The conversion into a more stable substance is therefore needed. Published derivatization methods include the reduction of formaldehyde to methanol [6] and the addition of alcohols to form acetals [7]. Due to the simultaneous emission of methanol and formaldehyde during curing reactions, these derivatization methods cannot be used without any interferences. The most prominent way to derivatize formaldehyde is by the application of hydrazine species to form a stable Schiff base [8,9,10,11,12]. Thereby the primary amine specifically reacts with carbonyl functionalities [13]. Hydrazine derivates such as pentafluorophenylhydrazine (PFPH) or 2,2,2-trifloro-ethylhydrazine (TFEH) are known to form thermally stable derivatization products with aldehydes, which makes them suitable for GC–MS [14].

Unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH) was recently described as a potential reagent for the quantification of aldehydes using an HPLC–DAD method [11]. It is a stable component that acts as a strong reducing agent. The volatility of UDMH is very high compared to other hydrazines, which makes gas phase derivatization reactions possible even at low temperatures. UDMH is commonly used as a fuel in the space industry. During combustion, it can disintegrate into even more toxic compounds that can migrate into soil, water or air. Its hazardous characteristics and thermally initiated degradation are one of the main reasons why UDMH and its transformation products are an important topic in environmental analysis [15,16,17].

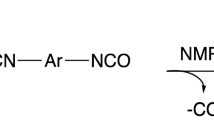

Formaldehyde dimethylhydrazone (FDMH) is one of the transformation products that occur when formaldehyde reacts with UDMH (Scheme 1) [18]. The reaction equilibrium is in favor of the products.

Under these aspects, this work provides insights into the stability of UDMH and FDMH under inert conditions. Furthermore, the usage of UDMH as a derivatization agent for an HS-GC–MS method with a focus on the simultaneous quantification of methanol emissions during the curing of melamine resin-polyester systems is discussed.

Experimental

Chemicals and Samples

UDMH (98%) and methanol (LC–MS grade) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and Honeywell. Commercially available formaldehyde was purchased in the form of an aqueous formalin solution from Sigma Aldrich. Iodometry and a standard liquid injection GC–MS method were utilized to quantify the levels of formaldehyde and methanol in the formalin solution, revealing concentrations of 36.57 wt.% for formaldehyde and 11.67 wt.% for methanol. For the stock solution, methanol was added to the formalin resulting in an aqueous solution with 30.60 wt.% formaldehyde and 26.10 wt.% methanol. The derivatization agent was used without any further dilution. As a sample, hexamethoxymethylmelamine (HMMM, Cymel 300) from Allnex was mixed with a commercially available model coating based on a linear polyester-polyol system with a Mw of 2000 in a ratio of 30:70.

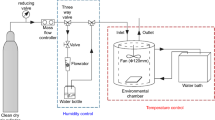

Headspace-GC–MS

All measurements were performed on a GC (Thermo Scientific, Trace GC Ultra) coupled to a MS (Thermo Scientific, ISQ) with an automated headspace sampler (Thermo Scientific, TriPlus RSH) in static mode. A ZB-624 column (30 m × 0.32 mm I.D., film thickness 1.80 µm) was used with a constant helium flow. The oven temperature was first held for 1 min at 40 °C, heated to 80 °C with 3 °C min−1, and lastly heated to 240 °C with 20 °C min−1 and held for 6 min. The PTV- and MS-inlet were operated at 220 °C. A split flow of 80 mL min−1 was used. The headspace incubation temperatures were 100, 150, or 200 °C respectively, depending on the subsequent measurement. Incubation times varied between 0.1 and 60 min. Peak areas were assigned via SIM mode by using the most abundant fragmentation ions (FDMH: 72 m/z and methanol: 31 m/z), unless otherwise stated.

Sample Preparation

Coating samples between 2–3 mg were applied on an aluminium pan, weighed, and transferred into an inert headspace vial. Inert handling was performed in a glove box. Handling of the derivatization agent and the samples under inert conditions is necessary since it prevents unwanted oxidation, potential combustion, and the introduction of carbonyls from laboratory air into the headspace vials. Finally, 1 µL of UDMH was introduced into the headspace vial. The sample is then measured via HS-GC–MS.

Results and Discussion

Reactivity

To trace the emission of formaldehyde during the curing process it is necessary to achieve full conversion between formaldehyde and UDMH as quickly as possible. UDMH and formaldehyde are both very reactive components and form their reaction product rather fast in aqueous media [11]. To test the reactivity in a gas phase reaction a volume with a molar ratio of 2:1 (UDMH:formaldehyde) was introduced into a headspace vial and measured immediately. To avoid reactions before the measurement, both components were placed individually in aluminium pans. Testing the reactivity at 150 °C with incubation times between 0.1 and 10 min results in very similar FDMH quantities (Table 1). The low standard deviation indicates a full conversion even at very short reaction times and enables emission monitoring for a longer period.

The primary amine functionality of UDMH can undergo various side reactions that are mostly studied under the aspect of combustion. Currently, more than 80 transformation products from UDMH are known [19].

Since no combustion occurs while operating under inert conditions, new transformation products were assessed at different temperatures (Fig. 1). Therefore, 1 µL UDMH and 0.8 µL formaldehyde in the form of a formalin solution were each introduced into a headspace vial and measured at 100, 150, and 200 °C, respectively. The hydrazine is present in a large molar excess, to show potential degradation products more effectively. The analytes were assigned according to spectral databases and literature [19].

Transformation products (a: acetaldehyde, b: methyl formate, c: UDMH, d: N-(dimethylamino)-N-methylformamide, e: N-(ethylideneamino)-N-methylmethanamine, f: 2-(dimethylamino)acetonitrile, g: N,N-dimethylnitrous amide and h: not identified) of FDMH and UDMH characterized by HS-GC–MS at different temperatures (green line: 100 °C, orange line: 150 °C and brown line: 200 °C) with an incubation time of one hour (colour figure online)

During the thermal degradation of FDMH and UDMH, acetaldehyde was formed as a minor oxidation product at 200 °C. Due to the excess of UDMH, the aldehyde reacts further to N-(ethylideneamino)-N-methylmethanamine. As a result of oxidation processes, methyl formate might be formed indirectly from UDMH [20]. Formic acid and methanol are products from Fenton processes in liquid media, that are currently used for the catalytic detoxification of UDMH. Especially formic acid is known to develop fast during the oxidation of UDMH [21]. Interestingly, varying temperatures do not influence the amount of methyl formate generated. Nevertheless, further reactions of formic acid and its esters with trimethyl hydrazine and UDMH result in their respective amides [19]. The degradation and transformation reactions are particularly high at 200 °C since no UDMH could be detected. Another degradation product is also 2-(dimethylamino)acetonitrile. Product h in Fig. 1 could not be assigned via spectral databases. Interestingly it is the only compound that shows indirect properties. The molecular peak was assigned to a m/z ratio of 129. Fragmentation ions occurred at m/z ratios of 42, 58, 71 and 85. Due to its inverse characteristics, it is assumed to be an impurity within the derivatization agent, that is consumed in transformation processes. Overall, a drastic increase in thermally induced transformation products between 150 and 200 °C could be shown.

Liquid coating systems contain large amounts of organic solvents for viscosity adjustments. Mixtures of aromatic hydrocarbons partially include high boiling components, that are needed to achieve latent drying [22]. Less volatile solvents are also present in the pre-solubilized polyester resin, that was used as a sample. To avoid permanent condensation in the injection unit, temperatures above 200 °C have to be applied. This might lead to further unwanted transformation products of UDMH. UDMH and formalin were again introduced in equimolar amounts into a headspace vial, but measured with varying incubation times at 200 °C (Fig. 2).

Graph A shows the formation of increasing transformation products (brown solid line: N-(dimethylamino)-N-methylformamide, dark green dash-dot-dot line: N,N-dimethylnitrous amide, light green dotted line: 2-(dimethylamino)-acetonitrile, yellow dash-dot line: N-(ethylideneamino)-N-methylmethanamine) from FDMH and UDMH using different incubation times at 200 °C. Graph B discusses the formation of decreasing or constant products (dark green solid line: FDMH, black dotted line: UDMH) using the same method as graph A. The peak areas of the analytes were assigned via SCAN mode (colour figure online)

All transformation products were detected at 200 °C with incubation times of more than 5 min. For 2-(dimethylamino)acetonitrile and N-(ethylideneamino)-N-methylmethanamine a linear increase was found, while a near exponential increase could be shown for N-(dimethylamino)-N-dimethylformamide between 5 and 30 min. Due to structural similarities with N,N-dimethylnitrous amide, the high occurrence of N-(dimethylamino)-N-dimethylformamide cannot only be explained by different detector responses, but the formation seems to be highly favored. UDMH shows a constant behavior between 0.1 and 1 min, while after 5 min almost 25% of the residual derivatization agent is degraded. Although no degradation products were detected during this incubation time, it is most likely that some intermediates like organic acids are not detectable with this setup. The amount of FDMH produced stays within a standard deviation of ≤ 10% over several incubation times (Fig. 2, dark green solid line).

Further experiments were performed to investigate the stability of UDMH to distinguish products stemming from UDMH and FDMH. 1 µL of the derivatization agent was placed in an inert headspace vial three times and measured at 100, 150 and 200 °C (Fig. 3).

When comparing the stability graphs of FDMH/UDMH (Fig. 1) and UDMH (Fig. 3), dimethylamine and 1-methyl-2-methylenehydrazine are only detectable when pure UDMH is degraded at 200 °C. They are therefore assumed to be intermediates in the formation of other substances. Furthermore, the first oxidation stage products of UDMH include FDMH and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) [23]. The occurrence of FDMH at high temperatures is contradictory to the analysis method shown in this publication. It, therefore, needs careful assessment of the degradation process of UDMH. All transformation products were detected and the oxidation of UDMH to FDMH occurred within one hour at temperatures above 150 °C. FDMH was also found in minor but equal quantities at 30, 100, and 150 °C, which indicates low amounts of impurities in the derivatization agent. The use of a BLANK value is not necessary since the peak area within the standards compensates for the increased FDMH amount. In terms of thermal stability both, UDMH and FDMH, are stable enough within an incubation time of one hour at 150 °C under inert conditions to be used as a derivatization agent and to be quantitatively measured.

Addition of the Derivatization Agent

Stochiometric addition of most derivatization agents is not enough due to potential losses, side reactions, or low conversion. To assess the dosage of the derivatization agent different molar equivalents of UDMH were added in a headspace vial with a formalin solution. Each sample was measured with an incubation time of one hour at 150 °C (Fig. 4). A plateau is reached after about 2.2 molar equivalents, which marks the minimal needed amount of derivatization agent to achieve full conversion.

Method Development

Further method validation included calibration, accuracy testing, and precision. The calibration of methanol and formaldehyde was performed by diluting the stock solution with highly purified water (1:5, 1:10, 1:25, 1:50, 1:75, 1:100 and 1:150) and adding 1 µL of standard and 1 µL derivatization agent into an inert headspace vial. For methanol (1) and formaldehyde (2) a calibration equation was calculated. Linear regression is shown in Fig. 5. The response of the derivatized formaldehyde is significantly larger than that of methanol.

where Y is the peak area of FDMH and X is the formaldehyde (FA) content in µg in formula (1) and Y is the peak area of methanol (MeOH) and X is the methanol content in µg in formula (2).

The limit of quantification (LOQ) and the limit of detection (LOD) of the method are calculated according to [24]. The LOQ resulted in 2.08 µg for methanol and 2.09 µg for formaldehyde and the LOD for both analytes in 0.69 µg. To validate the method and to show that the calibration curve is accurate for several incubation times, samples were spiked with a standard containing 52.23 µg formaldehyde and 45.75 µg methanol. As a reference a sample without any spiking solutions was also prepared and measured. The difference between the emitted formaldehyde and methanol content per mass of liquid coating of the unspiked sample and the spiked coating sample was used to calculate the analyte content with formulas (1) and (2). The recovery for formaldehyde varies between 87 and 103% and for methanol between 95 and 109% depending on the incubation time (Table 2). Linear regression for both analytes was only done at an incubation temperature of 150 °C for one hour. The recovery for this method is 103% for formaldehyde and 99% for methanol. Nevertheless, non-calibrated incubation times can still be used with this method, but mostly show a much higher or lower recovery than calibrated analytes.

The precision was validated for the accuracy of the individual incubation times by measuring coating samples three times at the respective time. Lower incubation times (< 1 min) showed a higher potential for larger standard deviations (< 30%) for both analytes. At incubation times ≥ 1 min, the standard deviation was below 7% (Fig. 6).

Emission Monitoring

Since no methanol or formaldehyde is present in the polyester system, it can only occur as free formaldehyde in the HMMM solution, be a side product in melamine resin crosslinking or thermally/pH induced deetherification of HMMM. The reaction paths where methanol and formaldehyde are occurring as byproducts are depicted in Scheme 2. The split off of methanol from HMMM can spontaneously be achieved at high temperatures (180–200 °C). Lower temperatures still achieve the detachment of methanol, but take longer times. Depending on the degree of etherification, crosslinking of the melamine system is already possible at 120 °C. During crosslinking melamine resins, bonding is either formed via ether or methylene linkages. In either case, methanol is split off as a side product, while formaldehyde is only emitted in the latter [25]. Polycondensation of polyester-melamine systems also results in the emission of methanol. To quantify the analytes, the coating samples were measured three times, respectively, at seven incubation times (0.1, 0.3, 1, 10, 20, 30, and 60 min) at 150 °C (Fig. 6).

Methylolated melamine resins (1) have a random distribution of three distinct functionalities that are involved in specific reaction mechanisms: methylolated groups (light green), primary or secondary amines (light blue) and hydroxy methyl groups (light red). The reaction partners and products are indicated in the same color as the functionalities of the melamine resin. Melamine resins (1) can undergo selfcondensation (2) and form methylene bridge formation under the emission of formaldehyde (3, light red). Another reaction that includes formaldehyde as a byproduct is the demethylolation of melamine (5, light red). Polycondensation of melamine and a polyester results in ether linkages with methanol as a byproduct (4, light green). Also, primary or secondary amines can form methylene linkages even without the emission of formaldehyde (6, light blue). Depending on the polyester system R’ can be either a hydrogen atom, a carbon atom or a carbonyl functionality (colour figure online)

Free formaldehyde is the first component to be released. Considering that 1 mg of sample consists of 30 wt.% HMMM with ≤ 0.25% of free formaldehyde, the amount of free formaldehyde should be ≤ 0.75 µg mg−1. This is in accordance with the first two incubation times (0.1 and 0.3 min). The cleavage of the ether linkages in HMMM leads to an increase in methanol production after 0.3 min and the formation of partially etherified HMMM. The unprotected hydroxy groups can then undergo self-condensation to form oligomeric structures, polycondensation with the polyester system, or a thermally initiated release of formaldehyde. Another formaldehyde source is the elimination of formaldehyde from ether bridges of oligomeric melamine structures. The highest emission rate for methanol is about 0.8 µg mg−1 min−1 and for formaldehyde 1.8 µg mg−1 min−1. Both rates were found at an incubation time of ≤ 1 min. At incubation times ≥ 1 min the rate of formaldehyde produced decreases again until the quantity of methanol and formaldehyde are nearly identical after 20 min, resulting in about 10 µg each. After about 30 min the emission rates of both analytes show a similar decreasing behavior.

Since the amount of analyte produced is highly dependent on the crosslinking agent, comparative studies on the technical properties of different polymer systems or curability based on the production of methanol are aspects that can be assessed with these curing profiles.

Conclusion

A derivatization headspace-GC–MS method was successfully developed for quantifying formaldehyde and methanol during low-temperature (≤ 150 °C) curing. Formaldehyde is derivatized in a gas phase reaction with UDMH to form FDMH. Inert handling and low-temperature curing are needed to avoid thermal degradation (> 150 °C) of the derivatized products. The method enables the assessment of curing profiles of complex formaldehyde-based polycondensates. Low standard deviations (< 7%) during repeatability testing and low quantification limits for formaldehyde (2.09 µg) and methanol (2.08 µg) make comparative studies on technical properties or curability possible.

Data Availability

The data from this work will be provided upon reasonable request.

References

Blank WJ (1979) Reaction mechanism of melamine resins. J Coat Techn 51:61–70

Kim K-H, Jahan SA, Lee J-T (2011) Exposure to formaldehyde and its potential human health hazards. J Environ Sci Health C Environ Carcinog Ecotoxicol Rev 29(4):277–299

Moon C-S (2017) Estimations of the lethal and exposure doses for representative methanol symptoms in humans. Ann Occup Environ Med 29:44–44

McGuire JM, Nahm SH (1991) Determination, by GC-MS using deuterated internal standards, of formaldehyde and methanol evolved during curing of coatings. J High Resol Chromatogr 14(4):241–244

Molavi H, Yousefpour A, Mirmostafa A, Sabzi A, Hamedi S, Narimani M, Abdi N (2017) Static headspace GC/MS method for determination of methanol and ethanol contents, as the degradation markers of solid insulation systems of power transformers. Chromatographia 80(7):1129–1135

Hu H-C, Tian Y-X, Chai X-S, Si W-F, Chen G (2013) Rapid determination of residual formaldehyde in formaldehyde related polymer latexes by headspace gas chromatography. J Ind Eng Chem 19(3):748–751

Del Barrio M-A, Hu J, Zhou P, Cauchon N (2006) Simultaneous determination of formic acid and formaldehyde in pharmaceutical excipients using headspace GC/MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal 41(3):738–743

Ding N, Li Z, Hao Y, Zhang C (2022) Design of a new hydrazine moiety-based near-infrared fluorescence probe for detection and imaging of endogenous formaldehyde in vivo. Anal Chem 94(35):12120–12126

Li Z, Jacobus LK, Wuelfing WP, Golden M, Martin GP, Reed RA (2006) Detection and quantification of low-molecular-weight aldehydes in pharmaceutical excipients by headspace gas chromatography. J Chromatogr A 1104(1–2):1–10

Prabhu P, Shelton CT (2011) Detection and quantification of formaldehyde by derivatization with pentafluorobenzylhydroxyl amine in pharmaceutical excipients by static headspace GC/MS. Perkin Elmer Application Note

Zhao J, Liu F, Wang G, Cao T, Guo Z, Zhang Y (2015) High performance liquid chromatography determination of formaldehyde in engine exhaust with unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine as a new derivatization agent. Anal Methods 7(1):309–312

Schenk J, Carlton DD, Smuts J, Cochran J, Shear L, Hanna T, Durham D, Cooper C, Schug KA (2019) Lab-simulated downhole leaching of formaldehyde from proppants by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), Headspace gas chromatography-vacuum ultraviolet (HS-GC-VUV) Spectroscopy, and headspace gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (HS-GC-MS). Environ Sci Process Impacts 21(2):214–223

Szulejko JE, Kim K-H (2015) Derivatization techniques for determination of carbonyls in air. TrAC, Trends Anal Chem 64:29–41

Kishikawa N, El-Maghrabey MH, Kuroda N (2019) Chromatographic methods and sample pretreatment techniques for aldehydes determination in biological, food, and environmental samples. J Pharm Biomed Anal 175:112782–112782

Chai Y, Chen X, Wang Y, Guo X, Zhang R, Wei H, Jin H, Li Z, Ma L (2023) Environmental and economic assessment of advanced oxidation for the treatment of unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine wastewater from a life cycle perspective. Sci Total Environ 873:162264–162264

Hu C, Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Liu Z-F, Feng X-S (2022) Unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine and related compounds in the environment: recent updates on pretreatment, analysis, and removal techniques. J Hazard Mater 432:128708–128708

Kosyakov DS, Ul’yanovskii NV, Pikovskoi II, Kenessov B, Bakaikina NV, Zhubatov Z, Lebedev AT (2019) Effects of oxidant and catalyst on the transformation products of rocket fuel 1,1-dimethylhydrazine in water and soil. Chemosphere 228:335–344

Dallas JA, Raval S, Alvarez GJ, P., Saydam S., Dempster A. G., (2020) The environmental impact of emissions from space launches: a comprehensive review. J Clean Prod 255:120209–120209

Milyushkin AL, Karnaeva AE (2023) Unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine transformation products: a review. Sci Total Environ 891:164367–164367

Kenessov BN, Koziel JA, Grotenhuis T, Carlsen L (2010) Screening of transformation products in soils contaminated with unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine using headspace SPME and GC-MS. Anal Chim Acta 674(1):32–39

Makhotkina O, Kuznetsov E, Preis S (2006) Catalytic detoxification of 1,1-dimethylhydrazine aqueous solutions in heterogeneous fenton system. Appl Catal B 68(3–4):85–91

Stout LR (2000) Solvents in today’s coatings. In: Applied polymer science: 21st Century. Elsevier, pp 527–543

Wu J, Bruce FNO, Bai X, Ren X, Li Y (2023) Insights into the reaction kinetics of hydrazine-based fuels: a comprehensive review of theoretical and experimental methods. Energies 16(16):6006–6006

Green JM (1996) Peer reviewed: A practical guide to analytical method validation. Anal Chem 68(9):305A-309A

Merline DJ, Vukusic S, Abdala AA (2013) Melamine formaldehyde: Curing studies and reaction mechanism. Polym J 45(4):413–419

Funding

Open access funding provided by Johannes Kepler University Linz. This work is funded by the FFG (Austrian Research Promotion Agency) under grant 898670 and 906791.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ER: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization. CS: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—Review & Editing, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing financial or personal interests, which could have influenced this work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rippatha, E., Schwarzinger, C. Simultaneous Analysis of Formaldehyde and Methanol Emissions During Curing Reactions of Polyester-melamine Coatings. Chromatographia 87, 275–283 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10337-024-04325-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10337-024-04325-z