Abstract

Studies on the foraging ecology of wildlife species are of fundamental importance, as foraging decisions are closely linked to ecological key issues such as resource partitioning or population dynamics. Using Black grouse as a model system, we applied Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIRS) to address some key questions in foraging ecology: (1) does FTIRS allow for determining plant taxa and plant parts? Can FTIRS suggest variation in digestibility of food and physiological mechanisms of consumers? (2) Can FTIRS be used to track changes in diets among populations? (3) Can FTIRS capture plants' phenology and shifts in diet? To answer these questions, we analyzed crop and gizzard contents of Black grouse via FTIRS looking for specific spectra and bands of plant taxa and plant parts. We compared spectral signals of undigested plant material and intestinal droppings, gained from wild-living birds and from aviaries. Our analyses yielded characteristic spectral fingerprints for several food plants and plant parts. Spectral fingerprints could differentiate between needles of J. communis and P. mugo and between fruits of J. communis, Sorbus sp., and Vaccinium sp. Spectral signals differed more between undigested material and crop samples than between crop and gizzard samples. Differences were more pronounced for berries than for needles. Apart from these differences, some fingerprints persisted for certain food items. The diverse foraging regime of wild-living individuals compared to captive Black grouse was reflected by spectral signals. Thus, FTIRS is a promising approach to explore variation in food choice of grouse species by means of non-invasively gained fecal samples.

Zusammenfassung

Von Pflanzen zum Kot – eine Pilotuntersuchung zur Anwendung der Fourier-Transform-Infrarotspektroskopie (FTIRS) für Untersuchungen zur Ernährungsökologie von pflanzenfressenden Vogelarten

Untersuchungen zur Ernährungsökologie von Wildtieren sind von grundlegender Bedeutung, da Entscheidungen im Nahrungsverhalten eng mit ökologischen Kernthemen wie etwa der Ressourcenaufteilung oder der Populationsdynamik zusammenhängen. Anhand des Modellsystems „Birkhuhn“ (Tetrao tetrix) untersuchten wir die Anwendung der Fourier-Transform-Infrarotspektroskopie (FTIRS), um einige zentrale Fragen in der Ernährungsökologie zu bearbeiten: (1) ermöglicht FTIRS eine Bestimmung von Pflanzenarten und Pflanzenteilen? Liefert FTIRS Hinweise auf die Variation der Verdaulichkeit von Nahrung und auf physiologische Mechanismen im Konsumenten? (2) Können mittels FTIRS Unterschiede in der Nahrungswahl zwischen Tierpopulationen entdeckt und nachvollzogen werden? (3) Sind die Phänologie von Pflanzen und entsprechende Änderungen der Nahrungswahl mittels FTIRS zu erfassen? Um diese Fragen zu beantworten, analysierten wir den Kropf- und Mageninhalt von Birkhühnern mittels FTIRS und suchten dabei vor allem nach spezifischen Spektren und Banden von Pflanzenarten und Pflanzenteilen. Wir verglichen dabei die spektralen Signale von unverdautem Pflanzenmaterial mit jenen von Kotwalzen, der sowohl von freilebenden Vögeln als auch von Gefangenschaftstieren stammte. Unsere Analysen ergaben typische spektrale Fingerabdrücke für mehrere Nahrungspflanzen und auch für Pflanzenteile. Diese Fingerabdrücke ließen eine Unterscheidung zwischen den Nadeln des Gemeinen Wacholders (Juniperus communis) und der Latsche (Pinus mugo) zu oder zwischen den Früchten des Gemeinen Wacholders, von Sorbus sp. und Vaccinium sp.. Die spektralen Signale unterschieden sich stärker zwischen unverdautem Pflanzenmaterial und Kropfproben als zwischen Kropf- und Magenproben und die Unterschiede waren bei Beeren deutlicher als bei Nadelmaterial. Abgesehen davon blieben spektrale Fingerabdrücke bestimmter Nahrungsbestandteile auch nach der Verdauung bestehen. Die spektralen Signale spiegelten auch die unterschiedliche Nahrungszusammensetzung von freilebenden vs. in Gefangenschaft lebenden Tieren deutlich wieder. Wir stufen daher FTIRS als vielversprechende Methode ein, um die Variation in der Nahrungswahl von Raufußhühnern auf Basis nicht-invasiv gewonnener Proben zu analysieren.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Foraging ecology addresses behavioral decisions of animals related to the acquisition of food, which, together with other behavioral expressions, affect chances of survival and reproductive success (McFarland 1977; Gaillard et al. 2010). Foraging decisions of animals determine, where and when animals search for food, which resources are consumed and when foraging is ceased in favor of other behavioral expressions (Schoener 1971; Pyke et al. 1977; Stephens and Krebs 1986). Foraging behavior follows a cascade of hierarchical decisions, which might be attributed to different temporal and spatial scales (García et al. 2011; Frye et al. 2013) and which ultimately affect animals’ survivorship, fecundity, and dispersal (Owen-Smith et al. 2010). Studies on foraging ecology of wildlife species are thus of fundamental interest as foraging of animals is closely linked to major ecological issues like resource partitioning or population dynamics. In terms of conservation targets, studies on foraging ecology provide important basics for adequate conservation and management planning.

A series of ecological theories aim at explaining foraging decisions of animals, e.g., optimal foraging theory (Pyke et al. 1977; Bolhuis and Giraldeau 2005), predator–prey theory (Hassell 1978), or social foraging theory (Giraldeau and Caraco 2000). Optimal foraging theory comprises several decision categories including decisions on optimal diet, patch choice, allocation of time to different patches, or patterns and speed of movement (Pyke et al. 1977). According to key assumptions of the optimal foraging and the predator–prey theories, predators concentrate spatially, where ever prey density is high. For herbivores, this process might be taken as habitat selection. However, habitat choice of herbivores might be also driven by predator avoidance behavior, by avoidance of insects, or by preference of thermal shelter (Crawley 1983). In the case of vertebrate herbivores, food selection might not entirely be in line with optimal foraging theory with diets typically comprising many different plant species for several reasons (Crawley 1983): e.g., (1) too low abundance of preferred food might not allow for selective foraging on the most preferred plant species; (2) food quality might not justify the costs of discriminating in terms of searching time; (3) plant species that provide maximum energy intake might not compulsorily fulfil other dietary requirements like intake of vitamins; and (4) palatability of plants might change rapidly with time. Both food quality and predation risk might vary distinctly within a landscape, resulting in a foraging dilemma for herbivores, requiring ultimate choices between the extremes of high-quality food at locations with high predation risk or of low-quality food at locations with low predation risk (McArthur et al. 2014). The above-mentioned aspects might show huge variation in space and time. For example, abundance, nutritional value, and palatability of plants can differ considerably with season (Jakubas et al. 1989) or site (Frye et al. 2013) or as a result of herbivore foraging (Bryant and Kuropat 1980). Moreover, digestive systems of herbivores might adapt to defense strategies of plants even within a lifetime of an animal (Moss 1997) and predator densities might show pronounced fluctuations, thus affecting habitat choice and habitat use of herbivores. Finally, plant communities as well as plants’ functional traits (such as flowering and masting) have been shown to follow changes in time and space (Kantorowicz 2000; Hilton and Packham 2003), partially as a more or less quantifiable consequence of climate change (Schmidt 2006; Övergaard et al. 2007). Ultimately, all these factors might affect habitat choice and foraging behavior of herbivores and lead to related variation in population performance (Plucinski and Hunter 2001; Schnurr et al. 2002; Nopp-Mayr et al. 2012).

To address responses of herbivores in terms of foraging ecology, methods that provide comparable results at different spatial resolutions (García et al. 2011) and which maintain stable and applicable over time are needed. Developing and applying appropriate methods might be facilitated by the use of model systems or model species. For several reasons, grouse species lend themselves as model system for establishing new applications of analytical methods in foraging ecology: (1) they are classified as habitat specialists in many cases, ranging from food specialists to generalists in different areas, years, and seasons (Angelstam et al. 2000; Storch 2007; Frye et al. 2013). Foraging behavior of grouse species frequently shows plasticity (Pauli 1978; Starling-Westerberg 2001) and diet switching (Crawley 1983) is a known phenomenon. Some grouse species follow bottom-up processes in population dynamics [i.e., fluctuations in populations’ numbers in relation to fruiting of preferred food plants (Selas 2000)]. Consequently, several major ecological issues might be addressed using grouse as model system. (2) Grouse species defecate at comparatively constant intervals (Klaus et al. 1989; De Juana 1994) and the intestinal droppings are highly resistant to decay processes (Poggenburg et al. 2018). Hence, they offer the opportunity for simple, stable and non-invasive sampling. (3) Grouse produce two different kinds of feces, i.e., caecal droppings, which represent the result of microbial fermentation activity and thus show a high degree of modification and intestinal droppings, which do not pass the caeca and thus have a high content of more or less intact fibrous plant remains (Watson and Moss 2008). (4) Intestinal droppings might be roughly assigned to seasons in terms of shape and content. (5) Studies on foraging ecology of grouse species have a long history (Swanson 1940), peaking between the 1930s and 1990s and becoming less prominent afterwards (Moss et al. 2010). Thus, basic knowledge on foraging behavior is available, providing a useful basis for methods´ calibration and evaluation. (6) Grouse species are hunted in many parts of their distribution, which holds the potential for gaining crop and gizzard samples invasively, providing reference data for non-invasively gained samples (feces). (7) Many grouse species might be kept in captivity, allowing for food choice and other foraging experiments under controlled circumstances (e.g., Moss 1997; Schroth et al. 2005; Siano et al. 2011).

Traditional methods for exploring foraging behavior of grouse species such as direct observations of (tagged) birds, microscopic analyses of crop and gizzard contents (of hunted individuals) or of intestinal droppings (collected in the field) are costly in terms of labor (Keller 1979; Remington and Braun 1985; Bertermann et al. 1998). Such methods are frequently restricted to comparatively small sample sizes, to single seasons or small areas of occurrence. Recently, DNA metabarcoding was applied to determine primary animal and plant components in the diet of grouse species (Sullins et al. 2018). Despite the advantage, the DNA metabarcoding is an accurate, high-resolution, and comparatively cheap method that can be used for non-invasively gained fecal samples (Sousa et al. 2019), and it also has some limitations: it needs advanced expertise, it requires a comprehensive, established reference library, and it might be biased by plant contamination (Ando et al. 2018). FTIRS holds the potential for a broad application in studies on foraging ecology, as it represents a cheap, non-invasive opportunity to understand, monitor, and ultimately to manage foraging of herbivores. Moreover, FTIRS provides an opportunity to assess hypotheses related to the physiological mechanisms of herbivory, using feces as the in vivo window to plant–herbivore interactions. So far, Url et al. (2015) applied FTIRS to compare band positions and band heights of intestinal droppings of Black grouse (Tetrao tetrix L.) and undigested reference plant material, both collected in the field. However, the “true” content of droppings with a more detailed classification of plant taxa or plant parts (buds, shoots, leaves, fruits, and seeds) was not addressed within this pilot study.

Our study uses spectral signals to link what plants are available in habitats to what plants are consumed and digested by the model species. We used various, separate samples in our analysis including (a) crop and gizzard contents of hunted Black grouse individuals, (b) undigested plant material, collected in the field, (c) intestinal droppings of wild-living birds, collected in the field, and (d) food and intestinal droppings of grouse individuals kept in captivity.

Using Black grouse as a model system and applying FTIRS, we validated a method that could address the following key questions in foraging ecology: (1) food choice: does FTIRS provide an appropriate method to determine plant taxa and plant parts, potentially consumed by herbivores? Does FTIRS tell us anything about quality (digestibility) of plant parts being consumed and about physiological mechanisms of the consumers? (2) Spatial variation in food choice: does FTIRS hold the potential to determine changes in diets among populations of herbivores? (3) Temporal variation in food choice: does FTIRS offer the opportunity to capture aspects of plants’ phenology and shifts in diet relative to changes in habitats?

Materials and methods

Black grouse as model system

Black grouse is a galliform species with a distribution range from Great Britain to Siberia (BirdLife International 2016). It is listed in Annex I and II of the EU Birds Directive (Directive 2009/147/EC). In Central Europe, core areas of Black grouse distribution lie in the Alps (Klaus et al. 1990; Glutz von Blotzheim 1994), where the species mainly inhabits the treeline ecotone (Sachser et al. 2017). According to Storch (2007), Black grouse might be taken as an indicator species of this ecotone. Dwarf shrubs are important food sources as they can be directly consumed by adults or offer arthropods for juvenile nutrition (Wegge and Kastdalen 2008; Signorell et al. 2010; Patthey et al. 2011). In winter, woody plants that overtop the snow layer act as food sources. Adult Black grouse primarily use two main food sources, i.e., parts of heather (Ericaceae) species and conifers (Pinaceae), whereas other plants are classified as additional food (e.g., Pauli 1974; Zettel 1974; Zbinden 1984; Marti 1985; Glutz von Blotzheim 1994; Picozzi et al. 1996; Wegge and Kastdalen 2008). There is a seasonal change in the availability of food plants and the different parts of plants. During wintertime, Black grouse use food that contains a higher amount of crude fibers, switching to more protein-rich parts of the plants available in spring (Gremmels 1986).

Crop and gizzard contents of hunted Black grouse

We analyzed crop and gizzard contents of 50 Black grouse males. The samples originated from the Piccole Dolomiti (Italy, 45°53′N, 11°02′E) from altitudes between 1400 m and 1900 m a.s.l.. In this region, Black grouse hunting season starts in the middle of October and lasts until the middle of December. We separated crop and gizzard contents into pure fractions of plant taxa and plant parts (i.e., leaves, shoots, flowers, fruits and seeds of the respective plant taxa) using a light microscope (Zeiss, Primo Star). Altogether, we separated 832 pure fractions with a range of 2–30 pure fractions in the crops and 4–22 pure fractions in the gizzards. We did not stain the samples, as this would have altered the chemical composition and thus the resulting spectral signals. The macroscopic identification was based on personal experience, supported by literature (mainly Aeschimann et al. 2004; Eggenberg and Möhl 2007; Fischer et al. 2008), herbarium specimens, and reference samples used for comparison of specific features (e.g., nature and type of hairs or bud scales; see Zettel 1974; Lieser 1996; Beeston et al. 2005). However, no comprehensive species reference collection or species list from the area, where the hunted individuals stemmed from, were available. While plant fragments from the crop samples often were in a relatively good condition, those from gizzards were partly digested. Exceptionally, those samples still showed characteristic details like the rust-colored scales at the leaf of Rhododendron ferrugineum (Fig. 1). Identification to genus or species level was possible in 46% of cases (i.e., 382 out of 832 pure fractions).

Field samples of undigested plant material

Samples of undigested plant material were collected in three Austrian study areas (Teufelstein/Styria, Tennengebirge/Salzburg and Hohe Tauern/Eastern Tyrol). We separated these 39 samples into 12 pure fractions (in terms of taxa and plant parts) with 1–5 replications per pure fraction (Table A-1).

Field samples of intestinal droppings of wild-living birds

To compare the spectral patterns of droppings from captive individuals with droppings from wild grouse individuals, we used field samples of intestinal droppings (n = 20) originating from previous field studies in Styria (Sachser et al. 2017). The dry field samples were stored in paper bags at room temperature.

Food and intestinal droppings of grouse individuals kept in captivity (aviary samples)

To explore changes in chemical composition and thus in spectral signals of plant material in the course of digestion, we compared spectral patterns of selected plant taxa/parts before and after digestion. We received 27 fecal samples of captive grouse individuals (n = 4) of the “Alpenzoo Innsbruck” and the “Wildpark Mautern”. Synchronously, samples of the daily offered diet were collected including both fresh plants as well as ready-made food mixtures. All samples were collected within 3 weeks, from October 11 to November 2, 2018 in the “Alpenzoo Innsbruck” and from October 1 to October 23, 2018 in the “Wildpark Mautern”. Both the intestinal droppings of the captive birds and food samples allowed for comparisons of spectral signals of digested and undigested known food items.

Sample preparation

All samples (i.e., ready-made food mixtures, undigested plant material, crop samples, gizzard samples, and intestinal droppings) were treated in the same way: Samples were dried in a drying oven at 80 °C for 24 h, a method proven not to influence spectral characteristics (Duboc et al. 2016). The dried samples were ground with a vibratory disc mill (Fritsch® Pulverisette 9) for 60–80 s and 1000 rotations per minute. In case of very low quantities, the samples were manually ground with a mortar, yielding a homogenous powder that allowed for reliable measurements of FTIR spectra.

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

FTIR spectra were recorded on a Bruker® FTIR spectrometer (Tensor 27) in the Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) mode. At a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1, 32 scans were collected. Five to ten replicates of each sample were performed. The replications were vector-normalized and averaged with the integrated software OPUS® 7.2.

Statistical analyses

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of selected spectral regions (i.e., 4000–2400 and 1800–400 cm−1) was performed with The Unscrambler® X 10.1 software to display the influencing factors (i.e., wild vs. captive birds, undigested material vs. intestinal droppings; Esbensen 2012). The excluded spectral region (2400–1800 cm−1) contains no signals of any relevant functional group but only disturbing signals of the diamond crystal.

Crop and gizzard samples showed high variability in composition and in proportions of pure fractions between individuals resulting in limited replication per fraction. We thus decided to compare averaged spectra of crop and gizzard samples with the spectra of fresh, undigested material in a descriptive way.

Results

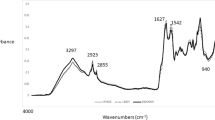

Spectral signals of selected, undigested plant taxa and plant parts—fingerprints

Our analyses brought evidence that plant taxa and also plant parts may produce specific spectral signals, which might be used as spectral fingerprints. Accordingly, Fig. 2 displays the spectral signature of undigested needles of Juniperus communis and Pinus mugo, and of undigested berries of Sorbus sp., J. communis, and Vaccinium myrtillus. These samples represent potential input material for further digestion processes. It is evident that plant parts like berries or needles feature specific patterns.

Average FTIR spectra of fresh, undigested plant parts (needles and berries) of selected plant taxa (Juniperus communis, Pinus mugo, Sorbus sp, and Vaccinium myrtillus). Vector-normalized spectra are shown for selected spectral regions (4000–2400 and 1800–400 cm−1). For band assignments see Table 1. Spectra are shifted along the y-axis for better representation

Furthermore, even within one group of plant parts, specific markers of different taxa may be found as it is the case with Juniperus needles containing Ca-oxalate, displayed by small but conspicuous bands at 1612 cm−1, 1316 cm−1, and 781 cm−1 (Franceschi and Nakata 2005; Piro et al. 2018; Tintner et al. 2018). All organic materials—from undigested plant material to the intestinal droppings—contain huge OH bands originating from diverse organic macromolecules. Methyl (CH3) and methylene (CH2) bands with maxima at 2920 cm−1 and 2850 cm−1 represent the backbone of many macromolecules. These bands indicate degradation and stabilization of organic matter during microbial transformation processes (Smidt et al. 2005).

Dynamics and persistence of markers in the course of digestion—the picture of crop and gizzard contents

Comparing spectral signals of undigested plant material with food items gained from crops and gizzards of wild grouse individuals showed distinct differences for certain bands. For example, the emerging band at 3010 cm−1 and the remarkable increase of intensity of methylene bands at 2920 and 2850 cm−1 (Fig. 3) exceed the common amplitude of normal degradation processes due to weathering (Tintner and Smidt 2018) or microbial decay (Meissl et al. 2008). The band at 3010 cm−1 can be assigned to the double bound of unsaturated oils (Wang et al. 2008). The bands at 1602 cm−1 and 1390 cm−1 indicate the presence of carboxylates (Smith 1998). The band at 1713 cm−1 can be assigned to aldehydes and ketones (Smidt et al. 2002). The double band at 798 cm−1 and 779 cm−1 indicates a quartz gastrolith (Reig et al. 2002). The differences in spectral signals among plant taxa and parts are more pronounced between undigested plant material and crops than between crops and gizzards (Fig. 3).

Spectral characteristics of berries (Sorbus sp. and Vaccinium myrtillus), depicted for fresh, undigested material, crop samples, and gizzard samples, respectively. Average vector-normalized spectra are shown for selected spectral regions (4000–2400 and 1800–400 cm−1). For band assignments see Table 1. Spectra are shifted along the y-axis for better representation

However, apart from these differences, some fingerprints persist for certain food items when reaching the gizzard. The pattern of Rhododendron leaves (Fig. 4) corresponds to specifications in literature (Duboc et al. 2016). In contrast to berries, the spectral pattern of P. mugo needles and Rhododendron leaves is consistent even in crop and gizzard samples (Fig. 4). Only band intensities change marginally, e.g., the small band at 820 cm−1. The band at 1514 cm−1 can be assigned to the aromatic ring vibration of lignin. The broad band at around 1045 cm−1 is attributed to cellulose (Schwanninger et al. 2004). However, even though berries show differences in spectral signals between fresh, undigested material and gizzard samples, these patterns distinctly deviate from the spectral signals of leaves (Fig. 3 vs. Fig. 4).

Spectral characteristics of needles (Pinus mugo), depicted for fresh, undigested material, crop samples, and gizzard samples, and signals of leaves (Rhododendron), depicted for fresh, undigested material and crop samples, respectively. Average vector-normalized spectra are shown for selected spectral regions (4000–2400 and 1800–400 cm−1). For band assignments, see Table 1. Spectra are shifted along the y-axis for better representation

Fresh plants and droppings—fecal signals represent food intake

Species-appropriate feeding regimes in the aviaries showed spectra that differed distinctly from natural, high elevation foraging conditions (cf. Table A-1). Accordingly, intestinal droppings collected from the field also differed from aviary droppings. However, it is evident that the spectral signature of Rhododendron leaves is preserved in the spectral pattern of field droppings (Fig. 5).

Spectral characteristics of fresh, undigested material (leaves of Rhododendron spp. and yeast pellets) and intestinal droppings, gained from field sampling and from aviaries. Average vector-normalized spectra are shown for selected spectral regions (4000–2400 and 1800–400 cm−1). For band assignments see Table 1. Spectra are shifted along the y-axis for better representation

The food mixture for grouse kept in aviaries distinctly differs from field conditions, for instance in terms of yeast content. The spectral pattern of yeast was found to be comparable to literature (Berterame et al. 2016; Tareb et al. 2017). The bands at 3275 cm−1 and 1400 cm−1 can be assigned to the NH vibration of amines (Rozenberg and Shoham 2007) and to carboxylates in amino acids (Kumar et al. 2014; Mihoubi et al. 2017), respectively. The band at 1520 cm−1 represents the aromatic ring vibration of amino acids (Naumann et al. 1996). Again, the spectral signals of aviary droppings represent the food stuff consumed by captive grouse (Fig. 5).

Results of the PCA display the distinct separation of field and aviary droppings (Fig. 6). The position of undigested materials close to the respective dropping group indicates the strong representation of consumed foods in fecal signals.

Discussion

Our study yielded clear indications that FTIRS is a promising method for addressing key questions in herbivore foraging ecology. Food choice in terms of selected plant taxa and plant parts might be explored in a non-invasive and comparatively cost-efficient way. Thus, resource partitioning or bottom-up effects in population dynamics of herbivores, related to changes in plant phenology might be tracked over large temporal and spatial scales, which cannot easily be done with other direct (invasive) approaches. FTIRS additionally holds the potential to address food quality and digestibility and related aspects of their spatial and temporal variation. In the following, we address the key questions of our study more specifically.

Does FTIRS provide an appropriate method to determine plant taxa and plant parts (leaves, fruits etc.), potentially consumed by herbivores?

In our study, we could indeed observe characteristic spectral fingerprints for several potential food plants and plant parts of Black grouse including needles of J. communis and P. mugo or fruits of J. communis, Sorbus sp. and Vaccinium sp.. For example, spectra of J. communis needles differed from those of P. mugo by small, but conspicuous bands at 1612 cm−1, 1316 cm−1, and 781 cm−1. Thus, our study provided good indications, that both plant species and plant parts like fruits, leaves or needles might be determined via FTIRS. This outcome is consistent with first FTIRS analyses of food plants of Black grouse by Url et al. (2015). One prerequisite for non-invasively tracking food choice of grouse via feces is, that initially identified spectral fingerprints of food plants or plant parts are subsequently not significantly modified during digestion. In other words, fingerprints have to be more or less constant to detect features unique to plant taxa or plant parts to determine diet choices by herbivores. The chemical composition of feces and the resulting persistence of spectral markers strongly depend on the digestive system of target species and on the digestibility of consumed plant tissues (Pauli 1978).

Does FTIRS tell us anything about quality (digestibility) of plant parts being consumed and about physiological mechanisms of the consumers?

Typical characteristics of grouse food plants (with pronounced seasonal variability) are a comparatively low nutrient content (proteins, phosphorus and sodium) and a high content of ingestible components like fibers, tannins and resins (Höhn 1980; Watson and Moss 2008). However, plant parts (like berries) can have high nutritional quality and it is important to differentiate them.

The digestive process of grouse can alter spectral fingerprints and be a proxy for physiological mechanisms of the consumer. Addressing such mechanisms needs a clear picture of the digestive system of grouse, starting with undigested, fresh plants, continuing with the buccal cavity (saliva production) and ending with the large intestine and with released feces (see Robbins 1993). As for grouse species, the extensible crop is mostly described as an organ for food storage (Robbins 1993; Bergmann et al. 1996; Watson and Moss 2008), where ingested food might stay from a few seconds up to several hours (see Gremmels 1986). According to Klaus et al. (1989, 1990) and Robbins (1993), food is stored, defrosted and softened by saliva secretion in the crop. With the exception of the crop of Opisthocomus hoazin (Grajal et al. 1989), birds´ crop function is mainly described as storage and moistening organ (see Robbins 1993; Kierończyk et al. 2016). Only marginal notes indicate further possible functions such as a functional barrier for pathogens through decreasing pH values via microbial “fermentation” and a role in the “regulation of innate immune system” (Kierończyk et al. 2016). However, our analyses revealed a pronounced shift in chemical composition and thus in spectral signals of food items in the crop of Black grouse compared to patterns of fresh plant material. Such a shift was particularly obvious in berries of Vaccinium sp., where the intensity of methylene bands at 2920 cm−1 and 2850 cm−1 increased markedly in the crop samples, exceeding patterns of weathering and microbial decay (Meissl et al. 2008; Tintner and Smidt 2018). Two alternative explanations might account for these results: (1) a distinct process of decomposition is already taking place in the crop with enzymes (and likely microbes) altering the chemistry and spectra of food items compared to fresh plants, which has not been addressed or observed for (alpine) grouse species up to now; (2) food selection of grouse responds to chemical properties of food plants and thus spectral signals of selected food items might distinctly deviate from those of non-selected, but available fresh plant material. Diet selection may reduce the intake of plant secondary metabolites (PSMs), which has been demonstrated for different grouse species (Remington and Braun 1985; Jakubas et al. 1989; Frye et al. 2013). PSMs might induce high postingestive costs for herbivores, including detoxication processes and nutrient dilution (Jakubas et al. 1995), and birds may detect plants´ allelochemicals with their trigeminal sensory system (Jakubas and Mason 1991). Apart from such chemical senses, Siitari et al. (2002) provided some evidence that ultraviolet vision enables grouse to discriminate food items, potentially allowing them to select for ripe berries.

Much more prominent descriptions of the digestive tract of grouse exist for the strong second gizzard and the caeca (Höhn 1980; Moss and Hanssen 1980; Gremmels 1986; Klaus et al. 1989, 1990; Bergmann et al. 1996; Watson and Moss 2008): The second gizzard is a muscular organ with ridges, containing particles of grit, which allow for a grinding of coarse food items into fine particles. Comparing spectral patterns of undigested plant material with material gained from crops and gizzards in our study, shifts in spectral signals were more pronounced between undigested material and crops compared to differences in patterns between crops and gizzards. However, some fingerprints persisted in spite of observed changes in spectral signals. For example, R. hirsutum leaves and P. mugo needles retained spectral patterns with marginally changing band intensities, e.g., at 820 cm−1. These results support the idea of the above-described major function of the Black grouse gizzard as a grinding organ.

At the junction of the small and the large intestine, two paired, blind intestinal diverticula (= caeca) exist, where the more liquid fraction of chyme is further processed (Moss and Hanssen 1980; Robbins 1993). These caeca play an important role in the decomposition of plant fibers, as cellulose and lignin are fermented by microbes there. Moss and Parkinson (1972) observed significantly lower contents of lignin, cellulose and carbohydrates in the caeca than in the intestine. Furthermore, peristaltic contractions of the colon induce urine reflux to the caeca, providing oxygen for lignin decomposition there (Watson and Moss 2008). Output of the caecal digestion process are soft and shapeless feces (= caecal droppings), whereas the harder and less digestible fraction of chyme is excreted as fibrous, cylindrical feces (= intestinal droppings; see Moss and Parkinson 1972). Both types of feces represent different ways of digestion within the same grouse species (and individual) and different fractions of initial food intake. Consequently, larger and harder food particles might not reach the caeca and remain nearly unchanged in terms of spectral signals, whereas other softer particles (like berries) might be digested to a higher degree and thus may not be detected in fecal dropping and may be highly modified in caecal droppings. Tracking food remains in grouse feces using FTIRS and inferring food choice seems possible with intestinal droppings, whereas physiological modification of food by the consumer might be more adequately addressed by considering both intestinal and caecal droppings.

Spatial variation in food choice: does FTIRS hold the potential to determine changes in diets among populations of herbivores?

For ultimate statements on the applicability of FTIRS for a non-invasive determination of food items of grouse species and for comparisons among populations, spectral signals of undigested plant material have to correspond to signals of intestinal droppings. First FTIRS analyses of Url et al. (2015) provided an indication of this assumption, but direct links between undigested plant material and intestinal droppings were missing. In our study, FTIR spectra of dropping samples gained from aviaries and those of field samples yielded a distinct separation of these two dropping groups in terms of PCA scores. The diverse feeding regime (and related differences in anatomy and physiology, Moss 1997; Liukkonen-Anttila et al. 2000; Wienemann et al. 2011; Salgado-Flores et al. 2019) of captive birds compared to wild-living individuals thus became evident, particularly on the first PCA axis, which explained nearly 60% of the variability in spectra. Moreover, the spatial proximity of undigested plant material and droppings within the captive versus the wild-living group on the PCA plot supported the idea, that spectral signals of intestinal droppings might adequately reflect variation in food choice. As a consequence, FTIRS seems to be a promising approach, when coupled with reference FTIRS of fresh plants, to study and compare diets among populations of grouse.

Temporal variation in food choice: does FTIRS offer the opportunity to capture aspects of plants´ phenology and shifts in diet relative to changes in habitats?

In general, a large list of potential food plants of grouse species is already available (e.g., Zbinden 1984; Beeston et al. 2005). However, depending on the habitat, grouse show more or less distinct shifts in food choice with season or among years (Pauli 1974; Zbinden 1984; Marti 1985). These shifts may reflect the phenology of availability of plants, temporal modifications in plant chemistry (Jakubas et al. 1989) or changing energetic requirements of grouse. Additionally, various studies demonstrated, that both plant communities and their functional traits have distinctly changed within the last decades with an earlier start of flowering, an altered synchronization of flowering or with higher frequencies of masting events (Kantorowicz 2000; Hilton and Packham 2003; Övergaard et al. 2007) inducing bottom-up (Selas 2000; Plucinski and Hunter 2001; Schnurr et al. 2002) as well as top–down (Selas 2000) responses in herbivore species.

Particular plant parts might distinctly drive population dynamics of grouse species, as it has been shown for capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) and bilberry masting in Norway (Selas 2000). Thus, depending on the research target, analyses with FTIRS may hold a clear advantage to metabarcoding approaches (Sullins et al. 2018), which do not support the determination of specific parts of a plant. One pre-condition to track such effects, however, is, that plant species and plant parts, being available, might be determined via characteristic spectral markers (fingerprints).

Conclusions and further perspectives

Our study provided clear evidence, that FTIRS is a promising approach to explore variation in food choices of grouse species by means of non-invasively gained fecal samples. However, for a comprehensive applicability of the method, further developmental steps are necessary. This requires both further feeding experiments and fecal analyses to validate spectral correlations between undigested plant material (input of fresh food) and digested plant material (output of fecal droppings). Thereby, the design of feeding experiments seems to be crucial, as galliform birds show significant differences between wild and captive individuals in the caecal microbiome, in their physiology, in the morphology of the gastrointestinal tract and in resulting life histories (Moss 1997). Two implications are arising from this fact: the more artificial feeding and living conditions of captive birds deviate from natural conditions, the less the digestive system (in terms of gizzard weight, gut length and physiology) is comparable with wild-living birds. Unpredictable factors might be reduced by feeding experiments and links between plants and feces might be derived more clearly, but inference on the foraging ecology of wild birds might nevertheless be tricky. Apart from feeding experiments, a calibration with traditional microscopic methods and further efforts in calibrating FTIRS for quantitative analyses should be pursued.

Despite a solid number of sampled grouse individuals in our study, the high between-subject variability in terms of pure fractions of plant remains in crops and gizzards limited our analyses to descriptive rather than multivariate analyses. Targets for future studies thus should aim at higher numbers of replications (both for invasively and for non-invasively gained samples), which then could allow for comparing specific, highly indicative bands or spectral regions (i.e., fingerprints) in a multivariate statistical way (e.g., via derivatizing spectra and PCA). This could be done in several steps: (a) comparing spectral patterns of plant species and plant parts for fresh plant material and for crop contents, respectively; (b) comparing patterns for the same species or plant parts, but contrasting fresh plant material vs. crop contents; (c) comparing feces of animals eating high proportions of a defined plant species or a defined plant part versus those eating low proportions (or none); (d) contrasting patterns of fresh plants vs. crop contents vs. gizzard contents vs. fecal pellets separately (e.g., by selecting individuals with similar diets, based on crop analysis). These steps would allow for multivariate statistical analyses of the spectral differences between “treatments” and for detailed answers to the key ecological questions listed above.

Further support of the hypothesis that spectral signals of the same plant change in the course of digestion, but fingerprints persist could allow researchers to predict digestibility and physiological modification of food by host consumers and their microbes. Concretely, if spectra from plants were similar to those in feces, this would mean that animals are specializing (eating primarily one plant species or part) and that the modification of the plant by the consumer is minimal, which in turn would be an indication of low digestibility and detoxification of plants as they pass through crop, gizzard, small and large intestine. Vice versa, large changes in spectra would indicate, that the plant chemistry is being modified during its route through the intestine. Significant variation in spectra from single plants to feces could also indicate, that animals are eating mixed diets possibly interacting with each other and this could be an indication of habitat plant diversity, of movement of animals, or of the physiological state of animals. Summing up, our pilot study opens the floor for a variety of future studies in the field of foraging ecology.

References

Aeschimann D, Lauber K, Moser D, Theurillat J-P (2004) Flora alpina. Haupt Verlag, Bern

Ando H, Fujii C, Kawanabe M et al (2018) Evaluation of plant contamination in metabarcoding diet analysis of a herbivore. Sci Rep 8:15563. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32845-w

Angelstam P, Runfors O, Mikusinski G, Seiler C (2000) Long-term dynamics of three types of Black Grouse habitat in the centre and at the edge of the distribution range in Sweden. Cah Ethologie 20:165–190

Beeston R, Baines D, Richardson M (2005) Seasonal and between-sex differences in the diet of Black Grouse Tetrao tetrix. Bird Study 52:276–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/00063650509461400

Bergmann H-H, Klaus S, Müller F et al (1996) Die Haselhühner. Westarp Wissenschaften, Magdeburg

Berterame NM, Porro D, Ami D, Branduardi P (2016) Protein aggregation and membrane lipid modifications under lactic acid stress in wild type and OPI1 deleted Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Microb Cell Fact 15:39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-016-0438-2

Bertermann C, Weber-Sparenberg C, Pechura A et al (1998) Zur Ernährung von Alpenschneehühnern Lagopus mutus helveticus im Sommer. Egretta 41:15–26

Bolhuis J, Giraldeau L-A (2005) The behavior of animals: mechanisms, function and evolution. Blackwell Publishers, USA

Bryant JP, Kuropat PJ (1980) Selection of winter forage by subarctic browsing vertebrates: the role of plant chemistry. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 11:261–285

Crawley M (1983) Herbivory: the dynamics of animal–plant interactions. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford

De Juana E (1994) Family Tetraonidae (Grouse). In: Del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J (eds) Handbook of the birds of the world, vol 2. Lynx Editions, Barcelona, p 385

Duboc O, Tintner J, Zehetner F, Smidt E (2016) Does sample drying temperature affect the molecular characteristics of organic matter in soil and litter? A statistical proof using ATR infrared spectra. Vib Spectrosc 85:215–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vibspec.2016.05.002

Eggenberg S, Möhl A (2007) Flora Vegetativa. Ein Bestimmungsbuch für Pflanzen der Schweiz im blütenlosen Zustand. Haupt Verlag, Bern

Esbensen KH (2012) Multivariate data analysis—in practice: an introduction to multivariate data analysis and experimental design, 5th edn. repr. CAMO, Oslo

Fischer M, Oswald K, Adler W (2008) Exkursionsflora für Österreich, Liechtenstein und Südtirol. Biologiezentrum der Oberösterreichischen Landesmuseen, Linz

Franceschi VR, Nakata PA (2005) Calcium oxalate in plants: formation and function. Annu Rev Plant Biol 56:41–71. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144106

Frye GG, Connelly JW, Musil DD, Forbey JS (2013) Phytochemistry predicts habitat selection by an avian herbivore at multiple spatial scales. Ecology 94:308–314. https://doi.org/10.1890/12-1313.1

Gaillard J-M, Hebblewhite M, Loison A et al (2010) Habitat–performance relationships: finding the right metric at a given spatial scale. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 365:2255–2265. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0085

García D, Zamora R, Amico GC (2011) The spatial scale of plant–animal interactions: effects of resource availability and habitat structure. Ecol Monogr 81:103–121. https://doi.org/10.1890/10-0470.1

Giraldeau L-A, Caraco T (2000) Social foraging theory. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Glutz von Blotzheim UN (ed) (1994) Handbuch der Vögel Mitteleuropas. Band 5. Galliformes und Gruiformes, vol 2. Akademische Verlagsbuchhandlung, Wiesbaden

Grajal A, Strahl SD, Parra R et al (1989) Foregut fermentation in the hoatzin, a neotropical leaf-eating bird. Science 245:1236–1238

Gremmels H-D (1986) Das Verdauungssystem der Rauhfußhühner—Eine Übersicht zur Physiologie und Mikroanatomie dieses Organsystems. Z Für Jagdwiss 32:96–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02241243

Hassell MP (1978) The dynamics of predator–prey systems. Monogr Popul Biol 35:1–237

Hilton GM, Packham JR (2003) Variation in the masting of common beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) in northern Europe over two centuries (1800–2001). Forestry 76:319–328

Höhn OE (1980) Die Schneehühner: Gattung Lagopus. A. Ziemsen, Wittenberg Lutherstadt

Jakubas WJ, Mason JR (1991) Role of avian trigeminal sensory system in detecting coniferyl benzoate, a plant allelochemical. J Chem Ecol 17:2213–2221. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988002

Jakubas WJ, Gullion GW, Clausen TP (1989) Ruffed grouse feeding behavior and its relationship to secondary metabolites of quaking aspen flower buds. J Chem Ecol 15:1899–1917. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01012275

Jakubas WJ, Guglielmo CG, Vispo C, Karasov WH (1995) Sodium balance in ruffed grouse as influenced by sodium levels and plant secondary metabolites in quaking aspen. Can J Zool 73:1106–1114. https://doi.org/10.1139/z95-132

Kantorowicz W (2000) Half a century of seed years in major tree species of Poland. Silvae Genet 49:245–249

Keller H (1979) Zur Winternahrung des Birkhuhns Tetrao tetrix im subalpinen Fichtenwald der Nordalpenzone. Ornithol Beob 76:9–32

Kierończyk B, Rawski M, Długosz J et al (2016) Avian crop function: a review. Ann Anim Sci 16:653–678. https://doi.org/10.1515/aoas-2016-0032

Klaus S, Andreev V, Bergmann H et al (1989) Die Auerhühner. Die Neue Brehm-Bücherei, Magdeburg

Klaus S, Bergmann H-H, Marti C et al (1990) Die Birkhühner: Tetrao tetrix und T. mlokosiewiczi. A. Ziemsen, Wittenberg Lutherstadt

Kumar N, Thomas S, Tokas RB, Kshirsagar RJ (2014) Investigation on the adsorption characteristics of sodium benzoate and taurine on gold nanoparticle film by ATR–FTIR spectroscopy. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 118:614–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2013.09.014

Lieser M (1996) Zur Nahrungswahl des Auerhuhns Tetrao urogallus im Schwarzwald. Ornithol Beob 93:47–58

Liukkonen-Anttila T, Saartoala R, Hissa R (2000) Impact of hand-rearing on morphology and physiology of the capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus). Comp Biochem Physiol A: Mol Integr Physiol 125:211–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1095-6433(99)00174-9

Marti C (1985) Unterschiede in der Winterökologie von Hahn und Henne des Birkhuhns Tetrao tetrix im Aletschgebiet (Zentralalpen). Ornithol Beob 82:1–30

McArthur C, Banks PB, Boonstra R, Forbey JS (2014) The dilemma of foraging herbivores: dealing with food and fear. Oecologia 176:677–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-014-3076-6

McFarland DJ (1977) Decision making in animals. Nature 269:15–21

Meissl K, Smidt E, Schwanninger M, Tintner J (2008) Determination of humic acids content in composts by means of near- and mid-infrared spectroscopy and partial least squares regression models. Appl Spectrosc 62:873–880. https://doi.org/10.1366/000370208785284277

Mihoubi W, Sahli E, Gargouri A, Amiel C (2017) FTIR spectroscopy of whole cells for the monitoring of yeast apoptosis mediated by p53 over-expression and its suppression by Nigella sativa extracts. PLoS One 12:e0180680. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180680

Moss R (1997) Grouse and ptarmigan nutrition in the wild and in captivity. Proc Nutr Soc 56:1137–1145

Moss R, Hanssen I (1980) Grouse nutrition. Nutr Abstr Rev Ser B 50:555–567

Moss R, Parkinson JA (1972) The digestion of heather (Calluna vulgaris) by red grouse (Lagopus lagopus scoticus). Br J Nutr 27:285–298

Moss R, Storch I, Müller M (2010) Trends in grouse research. Wildl Biol 16:1–11. https://doi.org/10.2981/09-055

Naumann D, Schultz C, Helm D (1996) What can infrared spectroscopy tell us about the structure and composition of intact bacterial cells? In: Mantsch H, Chapman D (eds) Infrared Spectroscopy of Biomolecules. Wiley, New York, pp 279–310

Nopp-Mayr U, Kempter I, Muralt G, Gratzer G (2012) Seed survival on experimental dishes in a central European old-growth mixed-species forest—effects of predator guilds, tree masting and small mammal population dynamics. Oikos 121:337–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2011.19099.x

Övergaard R, Gemmel P, Karlsson M (2007) Effects of weather conditions on mast year frequency in beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) in Sweden. Forestry 80:555–565. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpm020

Owen-Smith N, Fryxell JM, Merrill EH (2010) Foraging theory upscaled: the behavioural ecology of herbivore movement. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 365:2267–2278. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0095

Patthey P, Signorell N, Rotelli L, Arlettaz R (2011) Vegetation structural and compositional heterogeneity as a key feature in Alpine black grouse microhabitat selection: conservation management implications. Eur J Wildl Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-011-0540-z

Pauli H-R (1974) Zur Winterökologie des Birkhuhn Tetrao tetrix in den Schweizer Alpen. Ornithol Beob 71:247–278

Pauli H-R (1978) Zur Bedeutung von Nährstoffgehalt und Verdaulichkeit der wichtigsten Nahrungspflanzen des Birkhuhnes Tetrao tetrix in den Schweizer Alpen. Ornithol Beob 75:57–84

Picozzi N, Moss R, Catt DC (1996) Capercaillie habitat, diet and management in a Sitka spruce plantation in central Scotland. Forestry 69:373–388

Piro OE, Echeverría GA, González-Baró AC, Baran EJ (2018) Crystal structure and spectroscopic behavior of synthetic novgorodovaite Ca2(C2O4)Cl2·2H2O and its twinned triclinic heptahydrate analog. Phys Chem Miner 45:185–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00269-017-0907-0

Plucinski KE, Hunter ML (2001) Spatial and temporal patterns of seed predation on three tree species in an oak–pine forest. Ecography 24:309–317

Poggenburg C, Nopp-Mayr U, Coppes J, Sachser F (2018) Shit happens ··· and persists: decay dynamics of capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus L.) droppings under natural and artificial conditions. Eur J Wildl Res 64:29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-018-1187-9

Pyke GH, Pulliam HR, Charnov EL (1977) Optimal foraging: a selective review on theory and tests. Q Rev Biol 52:137–154

Reig F, Gimeno-Adelantado JV, Moya Moreno MCM (2002) FTIR quantitative analysis of calcium carbonate (calcite) and silica (quartz) mixtures using the constant ratio method. Application to geological samples. Talanta 58:811–821. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0039-9140(02)00372-7

Remington TE, Braun CE (1985) Sage grouse food selection in winter, North Park, Colorado. J Wildl Manag 49:1055. https://doi.org/10.2307/3801395

Robbins CT (1993) Wildlife feeding and nutrition, 2nd edn. Academic Press, San Diego

Rozenberg M, Shoham G (2007) FTIR spectra of solid poly-l-lysine in the stretching NH mode range. Biophys Chem 125:166–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpc.2006.07.008

Sachser F, Nopp-Mayr U, Zohmann M et al (2017) Searching the right tie—expert-based vs. statistical niche modeling for habitat management at the alpine treeline ecotone. Ecol Eng 100:107–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.12.009

Salgado-Flores A, Tveit AT, Wright A-D et al (2019) Characterization of the cecum microbiome from wild and captive rock ptarmigans indigenous to Arctic Norway. PLos One 14:e0213503

Schmidt W (2006) Temporal variation in beech masting (Fagus sylvatica L.) in a limestone beech forest (1981–2004). Allg Forst J Z 177:9–19

Schnurr JL, Ostfeld RS, Canham CD (2002) Direct and indirect effects of masting on rodent populations and tree seed survival. Oikos 96:402–410

Schoener TW (1971) Theory of feeding strategies. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 2:369–404

Schroth K-E, Lieser M, Berthold P (2005) Zur Winternahrung des Auerhuhns (Tetrao urogallus) - Versuche zur Bevorzugung von Nadeln verschiedener Koniferenarten. Forstarchiv 76:75–82

Schwanninger M, Rodrigues JC, Pereira H, Hinterstoisser B (2004) Effects of short-time vibratory ball milling on the shape of FT-IR spectra of wood and cellulose. Vib Spectrosc 36:23–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vibspec.2004.02.003

Selas V (2000) Population dynamics of capercaillie Tetrao urogallus in relation to bilberry Vaccinium myrtillus production in southern Norway. Wildl Biol 6:1–11

Siano R, Herzog SA, Exo K-M, Bairlein F (2011) Nahrungswahl ausgewilderter Auerhühner (Tetrao urogallus L.) im Harz. Vogelwarte 49:137–148

Signorell N, Wirthner S, Patthey P et al (2010) Concealment from predators drives foraging habitat selection in brood-rearing Alpine black grouse Tetrao tetrix hens: habitat management implications. Wildl Biol 16:249–257. https://doi.org/10.2981/09-028

Siitari H, Viitala J, Hovi M (2002) Behavioural evidence for ultraviolet vision in a tetraonid species—foraging experiment with black grouse Tetrao tetrix. J Avian Biol 33:199–202. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-048X.2002.330212.x

Smidt E, Lechner P, Schwanninger M et al (2002) Characterization of waste organic matter by FT-IR spectroscopy: application in waste science. Appl Spectrosc 56:1170–1175. https://doi.org/10.1366/000370202760295412

Smidt E, Eckhardt K, Lechner P et al (2005) Characterization of different decomposition stages of biowaste using FT-IR spectroscopy and pyrolysis-field ionization mass spectrometry. Biodegradation 16:67–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-004-0430-8

Smith BC (1998) Infrared spectral interpretation: a systematic approach. CRC Press, USA

Sousa LL, Silva SM, Xavier R (2019) DNA metabarcoding in diet studies: Unveiling ecological aspects in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Environ DNA. https://doi.org/10.1002/edn3.27(edn3.27)

Starling-Westerberg A (2001) The habitat use and diet of Black Grouse Tetrao tetrix in the Pennine hills of northern England. Bird Study 48:76–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/00063650109461205

Stephens DW, Krebs JR (1986) Foraging theory. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Storch I (2007) Assessing Grouse habitats in the Alps. In: Bissonette JA, Storch I (eds) Temporal dimensions of landscape ecology. Springer, USA, pp 143–154

Sullins DS, Haukos DA, Craine JM et al (2018) Identifying the diet of a declining prairie grouse using DNA metabarcoding. Auk 135:583–608. https://doi.org/10.1642/AUK-17-199.1

Swanson G (1940) Food habits of the sharp-tailed grouse by analysis of droppings. J Wildl Manag 4:432–436. https://doi.org/10.2307/3796013

Tareb R, Bernardeau M, Amiel C, Vernoux JP (2017) Usefulness of FTIR spectroscopy to distinguish rough and smooth variants of Lactobacillus farciminis CNCM-I-3699. FEMS Microbiol Lett. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnw298

Tintner J, Smidt E (2018) Resistance of wood from black pine (Pinus nigra var. austriaca) against weathering. J Wood Sci 64:816–822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10086-018-1753-5

Tintner J, Smidt E, Aumüller C et al (2018) Taphonomy of prehistoric bark in a salt environment at the archaeological site in Hallstatt, Upper Austria—an analytical approach based on FTIR spectroscopy. Vib Spectrosc 97:39–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vibspec.2018.05.006

Url S, Schwanninger M, Nopp-Mayr U (2015) Analyses of Black Grouse (Tetrao tetrix) faeces with infrared spectroscopic methods. J Ornithol 156:635–646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-015-1160-2

Wang Y, Wang Q, Artz WE, Padua GW (2008) Fourier transform infrared spectra of drying oils treated by irradiation. J Agric Food Chem 56:3043–3048. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf073545m

Watson A, Moss R (2008) Grouse. HarperCollins Publishers, London

Wegge P, Kastdalen L (2008) Habitat and diet of young grouse broods: resource partitioning between Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) and Black Grouse (Tetrao tetrix) in boreal forests. J Ornithol 149:237–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-007-0265-7

Wienemann T, Schmitt-Wagner D, Meuser K et al (2011) The bacterial microbiota in the ceca of Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) differs between wild and captive birds. Syst Appl Microbiol 34:542–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.syapm.2011.06.003

Zbinden N (1984) Zur Herbstnahrung des Birkhahns Tetrao tetrix im Tessin in Jahren mit unterschiedlichem Vaccinien-Beerenangebot. Ornithol Beob 71:186–246

Zettel J (1974) Nahrungsökologische Untersuchungen am Birkhuhn Tetrao tetrix in den Schweizer Alpen. Ornithol Beob 71:186–246

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna (BOKU). We are grateful to the “Alpenzoo Innsbruck” and the “Wildpark Mautern” for the valuable cooperation and for supplying feeding stuff as well as dropping samples. We thank Karin Wriessing (Institute of Applied Geology, University of Natural Resource and Life Sciences, Vienna) and the Institute of Zoology, University of Natural Resource and Life Sciences, Vienna for providing their lab facilities for the sample preparation. We thank Josef Pennerstorfer (Institute of Forest Entomology, Forest Pathology and Forest Protection, University of Natural Resource and Life Sciences, Vienna) for the assistance during the photo documentation of the samples. We are grateful to Andreas Daim and Gert Niederkofler for collecting plant material. We cordially thank Veronika Grünschachner-Berger for her expert consultation and for sharing her field experience. Finally, we thank the three anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on previous versions of this manuscript and for encouraging stimuli for future studies.

Funding

We thank the Department of Integrative Biology and Biodiversity Research for financial support of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by F. Bairlein.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nopp-Mayr, U., Zohmann-Neuberger, M., Tintner, J. et al. From plants to feces: pilot applications of FTIR spectroscopy for studies on the foraging ecology of an avian herbivore. J Ornithol 161, 203–215 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-019-01718-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-019-01718-y