Abstract

To maximize fitness, animals choose habitats by using a combination of direct resource cues, such as the quality and quantity of safe breeding sites or food resources, and indirect social cues, such as the presence or breeding performance of conspecifics. Many reports show that nest predation leads to reduced fitness. However, it remains unclear how birds assess predation risk and how it affects breeding-site selection. In this study, we analyzed the relationship between predation risk and breeding-site selection in Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica). We assessed the cues that swallows use in their selection. We used nest-site characteristics related to predation and foraging sites as direct resource cues, number of breeding pairs, and breeding success in the previous year as indirect social cues, and number of old and undamaged old nests as direct resource and/or indirect social cues. Breeding-site preference was assessed using the arrival date of males. We showed that only the number of undamaged old nests was used for breeding-site selection. When comparing effects at two spatial scales, nest-site and home-range, the effect of the number of undamaged old nests occurred at the home-range scale only, suggesting that these nests are used as an indirect social cue rather than a direct resource cue to reduce the energy or time-consuming costs of nest building. We suggest that undamaged old nests may indicate the presence and breeding performance of conspecifics for several previous years. Because Barn Swallows are migratory birds, undamaged old nests may be a reliable indirect social cue and may reduce the time required to sample information at breeding sites.

Zusammenfassung

Bei der Brutplatzwahl bevorzugen Rauchschwalben soziale Signale gegenüber Ressourcensignalen

Für die Maximierung von Fitness wählen Tiere Habitate mit Hilfe einer Kombination aus direkten Ressourcensignalen, wie Qualität und Quantität sicherer Brutplätze oder Nahrungsressourcen, und indirekten sozialen Signalen, wie die Anwesenheit oder Brutleistung von Artgenossen. Viele Berichte zeigen, dass Nestprädation die Fitness verringert. Allerdings bleibt unklar, wie Vögel das Prädationsrisiko abschätzen und wie es die Brutplatzwahl beeinflusst. In dieser Studie haben wir die Beziehung zwischen Prädationsrisiko und Brutplatzwahl bei Rauchschwalben (Hirundo rustica) analysiert. Wir haben die Signale bewertet, die Schwalben für die Brutplatzwahl nutzen. Wir haben Brutplatzcharakteristika in Bezug zu Prädation und Nahrungssuchorte als direkte Ressourcensignale, die Anzahl der Brutpaare und Bruterfolg im vorherigen Jahr als indirekte soziale Signale und die Anzahl alter und unbeschädigter alter Nester als direkte Ressourcen- und/oder indirekte soziale Signale verwendet. Die Präferenz für einen Brutplatz wurde mit Hilfe des Ankunftsdatums der Männchen eingeschätzt. Wir zeigten, dass lediglich die Anzahl alter, unbeschädigter Nester für die Brutplatzwahl eine Rolle spielte. Ein Vergleich der Effekte auf zwei räumlichen Skalen, Brutplatz und Streifgebiet, zeigte, dass der Effekt der Anzahl unbeschädigter Nester lediglich für das Streifgebiet gegeben war, was darauf hindeutet, dass diese Nester eher als indirektes soziales Signal genutzt werden als als direktes Ressourcensignal, um den Energie- oder Zeitaufwand für den Nestbau zu verringern. Wir schlagen vor, dass unbeschädigte alte Nester das Vorhandensein und die Brutleistung von Artgenossen für mehrere vorangehende Jahre anzeigen könnten. Da Rauchschwalben Zugvögel sind, könnten unbeschädigte alte Nester ein verlässliches indirektes soziales Signal darstellen und die Zeit verringern, die aufgebracht werden muss, um Informationen über Brutplätze zu sammeln.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Birds are known to gather information about habitat quality before making decisions on habitat selection (Jones 2001; Dale et al. 2006). They select habitats by using a combination of direct resource cues, such as the quality and quantity of safe nest sites or food resources, and indirect social cues, such as the presence or breeding performance of conspecifics (Danchin et al. 2004; Dall et al. 2005).

Since nest predation is the main cause of reproductive failure leading to reduced fitness (Martin 1993), and the risk of predation varies among nest sites (Fontaine and Martin 2006), birds are expected to select nest sites that are safe from predation. Social information about habitat quality is easily gathered compared to information on individual experiences in a changing environment (Danchin et al. 2004).

However, it remains unclear how birds assess nest predation risk and how it affects other factors in the decision-making process for breeding-site selection (Eggers et al. 2006; Lima 2009). Additionally, although these factors and their interactions vary spatially and temporally, only a few studies have simultaneously assessed resource factors and social factors (but see Müller et al. 2005; Betts et al. 2008a). Most studies have used individual density as an indicator of habitat preference without obtaining direct estimates of habitat preference (Robertson and Hutto 2006). However, when habitat preference is assessed using the density of individuals alone, the actual effect of predation risk cannot be determined (Chalfoun and Martin 2007). This is because nest predation is related to fine-scale factors, such as nest-site characteristics, whereas density mainly represents large-scale effects, such as food availability (Pulliam 1988; Martin 1998).

High-quality breeding sites are settled first, and arrival time correlated with habitat preference in migrant birds (Aebischer et al. 1996; Currie et al. 2000). Since high-quality male swallows arrive at the nest sites first (Møller 1994), such nest sites might be preferable. If poor-quality males arrive late, all the good nest sites will probably have been selected and they would not have a real breeding-site selection. However, there are many buildings available for nest sites in our study area, and since there were more buildings without new nests than buildings with new nests, we think that the breeding-site selection of high-quality males does not influence that of other males. Although the date that females lay the first eggs was assumed as an indicator of breeding-site preference in birds (Forsman et al. 2008), it is affected by seasonal climate variables, such as temperature (Visser et al. 2009), and male quality (Helfenstein et al. 2003). Considering the direct effects of nest-site quality in breeding-site preference, it may be important to use the male arrival date as an indicator of breeding-site preference.

Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica) are migratory, insectivorous, small passerines (Turner and Rose 1989) that breed in close association with human activity and build nests on man-made structures such as barns, bridges, or residential houses. They build open cup-shaped nests and often reuse old nests built by conspecifics in previous breeding seasons (Barclay 1988; Møller 1990).

Here, we analyzed the relationship between predation risk and breeding-site selection in Barn Swallows by using male arrival date as an indicator of breeding-site preference. Several possible resource and social factors were considered as direct and indirect cues. First, we examined the nest-site characteristic related to the occurrence of nest predation. Second, we investigated the cues that are preferentially used in the process for breeding-site selection, including the nest-site characteristic related to predation as one of the direct resource cues.

Methods

Study area and species

From 2008 to 2010, we conducted field studies at three volcanic islands, Niijima (34°38′N, 139°26′E, 23.9 km2), Shikinejima (34°33′N, 139°22′E, 3.9 km2), and Kouzushima (34°21′N, 139°13′E, 18.9 km2), which are part of the Izu-Islands located about 47–52 km south of Tokyo, Japan. Since suitable breeding habitat ranges for swallows (i.e., residential areas) are patchy and limited on these islands, nests and breeding swallows are easily detected.

Barn Swallows breed from the end of March until the end of August. Generally, adult males arrive first and establish small breeding territories. After forming breeding pairs, they nest on buildings. Barn Swallows prefer to breed in barns and stables that contain cattle (Ambrosini et al. 2002a) and mostly nest in colonies, in Europe and North America. In contrast, in our study area, the Barn Swallow nests were mostly solitary and the nests were observed on residential houses or on stores. Further, nest predation during the breeding seasons in our study area was attributed to Jungle Crows (Corvus macrorhynchos) or Japanese Rat Snakes (Elaphe climacophora).

Nest location and individual monitoring

During the breeding season, we located and monitored active nests every day in Niijima and twice every 10 days in Kouzushima. Because of fewer active nests in Kouzushima than in Niijima, and because we complemented our information with that from building owners about the breeding schedule of swallows, periodic monitoring on the island seemed sufficient to estimate the breeding schedule. In 2010, the islands had a maximum of 66 active nests (Niijima, n = 47; Kouzushima, n = 19) where males arrived and became active, namely, including nests where males arrived but failed to breed. We recorded the egg-laying date, clutch size, hatching date, hatching success, fledging date, and fledging success. The arrival dates of males were only recorded in Niijima in 2010. After the swallows had settled at the nest sites and formed breeding pairs, we monitored the breeding schedule at each nest every 3 days.

Swallows were individually identified by marking nestlings (2008: n = 172, about 50 % of all nestlings; 2009: n = 398, about 95 % of all nestlings; 2010: n = 244, about 90 % of all nestlings) and breeding pairs (2009: n = 54, about 65 % of all breeders; 2010: n = 14, about 25 % of all breeders) by using combinations of colored plastic rings (A.C. Hughes) and individually numbered aluminum rings authorized by the Ministry of Japan Environment Agency. Breeding pairs were caught with butterfly nets while sleeping in the nests at night, and nestlings were caught from the nests by hand during the day.

Factors for determining nest-site characteristics related to predation

Nest predation

Predator species were determined using field signs such as nest damage, carcasses of nestlings, and broken eggs, in addition to information provided by the building owners where swallows nested. Crows were the main predators in our study area (85 % of all predation) and usually depredated all the eggs or nestlings simultaneously. Thus, we only analyzed the above datasets to determine nest-site characteristics related to predation.

Nest-site characteristics

Nest-site characteristics, such as concealment, are thought to decrease nest predation rates (Martin 1993). In addition, Barn Swallows build open-cup nests on the walls of buildings, and the building structure is thought to influence the number of fledglings (Fujita 1993). Therefore, we considered building structure and nest location to represent possible nest-site characteristics related to the occurrence of predation. The characteristics may be relatively stable compared to other predation related factors, such as local crow densities. Since stable characteristics are a reliable cue for habitat selection (Schlaepfer et al. 2002), we considered nest-site characteristics as a direct resource cue for breeding-site selection.

In our study area, most nests were located in buildings surrounded by at least three or four walls with an entrance, such as a garage or storage area. Thus, three nest-site characteristics associated with nesting location were evaluated: width and height of the entrance that crows could use to approach nests, and distance from the entrance to the nests.

In addition to nest-site characteristics, the proximity of people to nests was evaluated to determine predation risk. Birds breeding indoors tended to have lower predation rates than those that bred outdoors (Møller 2010). Furthermore, crows did not approach swallow nests when people were present (Ringhofer, unpublished data). Thus, we assumed that the proximity of people would likely reduce predation. We recorded the daytime presence and flow of people during observations of male arrival dates (see detailed description in “Breeding-site preference”). The proximity of people to nest sites (i.e., within 2–4 m) was divided into three levels: (1) no persons present within 30-min (level 1), (2) one person present every 15 min (level 2), and (3) at least one person almost always present every 5 min (level 3).

Variables for analyzing breeding-site selection

Breeding-site preference

We used the arrival date of males as indicators of breeding site preference and conducted observations at each existing nest at the onset of the breeding season (from March 22, 2010) in Niijima. Each nest site was monitored during two 15-min observations per day every 3 days. If a swallow appeared at the nest site at least once during an observation, we changed the observation schedule at that nest to two 1-h observations per day to determine if the male had actually settled at the nest site or was only searching for breeding sites.

To estimate reliable values reflecting breeding site preference, we did not include datasets of individuals that returned to the same nest sites used in the previous year to exclude the effect of site fidelity. We aimed to investigate how swallows select breeding-sites using cues in the current year, and site-faithful males might select nest sites based on cues from the beginning of previous breeding seasons. Also, we did not include datasets of individuals that moved from other nest sites because of breeding failure. Because most Barn Swallows in our study area were solitary breeders, we only used data for the first male that arrived at each nest site. During observations, we identified the age of the breeding individuals (adults or first-years) by visually checking the combination of colored plastic rings on their legs. Of all the males that arrived, 10 were locally born yearlings (born in Niijima). Two males that successful bred in the previous year moved to other nest sites this year. The 23 males used in our analysis included 7 first-time breeders.

Direct resource cues

We used nest-site characteristics related to predation (which we detected in our previous analyses on nest predation) and areas of potential foraging habitats as possible direct resource cues influencing breeding-site selection. Foraging habitats were represented by the total area of three types of vegetation, including forest, forest edge, and farmland, where foraging behavior by swallows was mainly observed during the breeding season (71/89 incidents in 2009). We analyzed a vegetation map provided by the Japanese Ministry of the Environment by using Arc GIS 9.3 (ESRI) to measure the areas of the three foraging habitats within a 250-m buffer of each nest site. We used a buffer size of 250 m because 85 % (n = 308) of foraging swallows observed during the peak of the breeding season (June) in 2009 were located within this range. This supports the results from previous studies on European swallow populations, in which >90 % of Barn Swallows foraged within a distance of 500 m from their nests (Møller 1987).

Indirect social cues

As possible indirect social cues for breeding-site selection, we focused on the number of breeding pairs and breeding success in the previous year. The number of breeding pairs was assumed to represent the presence of conspecifics. We also used this variable to control for the possibility that previous breeding pair density might affect the number of early-arriving individuals in the next year. Breeding success was defined as the number of total fledglings per pair at each nest site during the breeding season and was assumed to indicate the breeding performance of conspecifics.

Number of old nests

The number of old nests has been suggested to play a crucial role in breeding-site selection of Barn Swallows (Safran 2004). Nest predations were not rare in our study area. Since swallows build nests that remain for several breeding seasons and often reuse old nests (Barclay 1988; Møller 1990), if predation occurred at a nest, the damage to the nest likely remained, unless repaired. To repair damaged nests, swallows must spend more time and energy than that by individuals breeding in old undamaged nests (Barclay 1988; Cavitt et al. 1999). Therefore, we assume that the presence of old or undamaged nests or the extent of damages may be direct resource and/or an indirect social cue for breeding-site selection. If the number of undamaged old nests is related to breeding-site preference only at the finer spatial scale, the nest-site scale (see “Spatial scales for analysis” below for details), this can be regarded as a direct resource cue, because swallows can benefit from using an undamaged old nest instead of building a new nest. Conversely, if it is related only at the larger spatial scale, the home-range scale, this can be regarded as an indirect social cue, because it is important for swallows to breed near undamaged old nests, which could be indicators of a safe area with little or no predation risk.

Prior to the breeding season, we counted the number of old nests in our study area and categorized the degree of nest damage into four levels: (1) old nests with no or minimal damage to the edge, (2) nests with up to 50 % lost, (3) nests with 50–80 % lost, and (4) only the imprint of a nest remaining on the walls of buildings. Because swallow nests are broken during predation attacks by crows, we assumed that undamaged old nests (level 1) were nests that had not been recently depredated by crows.

Spatial scales for analysis

When analyzing breeding-site selection, we used indirect social cues, number of old nests, and number of undamaged old nests at two spatial scales. The large spatial scale was within a 250-m buffer of each nest and defined as the foraging-habitat range (i.e., the home-range scale; see “Direct resource cues” for more details). The finer spatial scale was the actual nest site, including the building. At the home-range scale, we summarized the values of the cues for all nests within 250 m of each nest site by using ArcGIS.

Statistical analysis

Nest-site characteristics related to predation occurrence

To examine the nest-site characteristics related to the incidence of predation, we included the occurrence of predation at each nest site (depredated: 1; not depredated: 0) as a response variable in generalized linear models (GLMs) assuming binomial distribution.

Since the three nest-site characteristics were intercorrelated, we first used principal component analysis (PCA) based on the correlation matrix to derive two components (Table 1). Principal component I (PCI) primarily represented the narrowness of the entrance, and principal component II (PCII) primarily represented the distance from the entrance to the nest. Then, we used PCI and PCII, proximity of people, and islands (Niijima or Kouzushima) as explanatory variables. We only analyzed nest-site datasets for which all records of the response and explanatory variables included in the models were available (n = 32). We first constructed the initial model by incorporating all the explanatory variables. Then, we conducted a series of stepwise deletion tests, where any nonsignificant explanatory variable was removed. The significance of the terms in the model was determined by calculating the deviance of the model with and without those terms and comparing the reduction in deviance with the Chi square test.

Breeding-site selection in swallows and predation risk

We tested whether swallows select breeding sites based on nest-site characteristics related to predation as a direct cue of predation risk or based on social cues that may indirectly indicate predation risk. We used GLMs with quasi-Poisson as the error distribution. The arrival date of males was the response variable representing breeding-site preference. Two types of direct resource cues (i.e., nest-site characteristics related to predation and potential foraging habitats), two types of indirect social cues (i.e., the number of breeding pairs and breeding success in the previous year), number of undamaged old nests, number of old nests, and individual age were used as the explanatory variables. Since the arrival dates were suggested to differ with age in European Barn Swallows (Balbontin et al. 2009), ages of males that arrive first at the nest sites were used. The considered spatial scales were the nest-site and home-range. We only used the datasets for nest sites where all records of the response and explanatory variables included in the models were available (n = 23). Since our sample size was limited, we investigated the breeding-site selection of swallows by using minimal variables and did not include the interactions between variables or the number of old nests for four different categories as explanatory variables. To investigate whether swallows select their breeding-sites based on the degree of damage to the old nests and whether they use undamaged old nests more frequently than other old nests, we included the numbers of undamaged old nests and total old nests. We tested the multicollinearity of the explanatory variables based on the value of variance inflation factor (VIF; Montgomery and Peck 1982). Since the VIF was >0.1 and <10 for all the variables (i.e., in the tolerance range; Bowerman and O’Connell 1990), all were used as the explanatory variables in the model. We selected the variables by using the same procedure as that used for the analysis of predation occurrence. The significance of the terms in the model was determined using F test. All analyses were conducted using R statistical software (R project for Statistical Computing; http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Nest-site characteristics related to predation

The incidence of nest predation (7/32 nests) was negatively related to the narrowness of the entrances (PCI; from the PCA of nest-site characteristics) to the buildings where swallows nested (Table 2). In contrast, none of the other variables indicated a risk of predation.

Breeding-site selection in swallows and predation risk

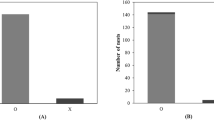

The number of undamaged old nests was negatively related to the arrival date of males at the home-range scale (i.e., within 250 m of the nest site), but not at the nest-site scale (Table 3; Fig. 1; n = 23). We detected no relationship between male arrival date and nest-site characteristics related to predation (i.e., narrowness of the entrances to the buildings where swallows nested). Other direct resource and indirect social cues were not related at either spatial scale.

Relationship between the arrival date of male Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica) and the number of undamaged old nests. Relative male arrival date is expressed as the number of day after the arrival date of the first male swallow at the nest site in our study area (considered as March 10, day1). The line represents the trend of the data

Discussion

The incidence of nest predation by Jungle Crows, the main predators of Barn Swallow eggs and nestlings, was reduced if the entrances to the buildings where swallows nested were narrow. Crows appeared to avoid approaching nests that were located in buildings with narrow entrances. Therefore, the narrowness of the entrance may make it more difficulty for crows to see inside a building or approach the nests.

In this study, we compared the significance of direct resource and indirect social cues for breeding-site selection in Barn Swallows. Our results indicate that, when male swallows select their breeding sites, they likely use an indirect social cue, such as the number of undamaged old nests.

A previous study on variation in the colony size of Barn Swallows (Safran 2004) suggested that old nests are a cue for settlement decisions by site-unfamiliar individuals. In this study, although we obtained a similar result showing the importance of undamaged old nests for site selection in male swallows, there were some differences. In addition to the number of old nests, we also focused on damage that might have been caused by predation. As described previously, most of the swallows in our study area were patchily distributed on the islands and were solitary breeders, and nest predation by crows was not rare. Thus, we considered possible resources and social cues to determine the breeding-site preference variables of individuals (i.e., male arrival date) rather than the settled number of individuals in breeding sites. As a result, we detected the actual and relative importance of possible cues for individual breeding-site selection in Barn Swallows. Our results and those of the previous study (Safran 2004) clearly show that, although there was a slight difference between the study sites, the presence of old nests at the beginning of the breeding season substantially influences decision-making in Barn Swallows.

The number of undamaged old nests was related to breeding-site selection in males at the home-range scale but not at the finer nest-site scale. Previous studies have suggested that old nests could be used by birds to reduce the costs (i.e., energy or time) of nest building (Cavitt et al. 1999). If swallows were attracted to undamaged old nests only as a means of reducing the cost of nest building and for use as direct resource cues, the presence of undamaged old nests should have also been related to breeding site selection at the nest-site scale. However, our findings did not support this hypothesis. Consequently, swallows likely used undamaged old nests as an indirect social cue that may indirectly predict resource quality and quantity.

A previous study in Europe investigated the effect of the presence of livestock on the number of breeding pairs at two spatial scales and showed that the presence of livestock are more influential at the nesting scale than at the foraging-range scale (Ambrosini and Saino 2010). This result appears to differ from our results in that breeding-site preference was related to the number of undamaged old nests at the home-range scale, but not the nest-site scale. We suspect that this discrepancy could arise from the relatively high level of predation risk at our study sites. Predation on eggs and nestlings, mainly by Jungle Crows, was common at our study sites. As previously explained (see above), because predation is likely to occur in a non-deterministic way and may be related to the home-range of such predators, it is likely to be difficult for swallows to make precise evaluations of predation risk at the nest-site scale (<10 m), while it could be possible at the home-range scale (≥250 m). We surmise that a certain number of undamaged nests at the home-range scale might be indicative of a low risk of predation by crows.

Among the possible indirect social cues, number of breeding pairs and breeding success in the previous year did not contribute to breeding-site selection. Birds have been shown to gather information about the presence and breeding performance of conspecifics during the breeding season to select a suitable breeding site in the following year (Pärt and Doligez 2003; Parejo et al. 2007; Betts et al. 2008b). However, the number of breeding pairs and breeding success provide information about the presence and breeding performance of conspecifics for a single year only, whereas undamaged old nests may provide information from several years. Thus, in birds that maintain nests over many seasons, such as swallows, an undamaged old nest may be a reliable indirect social cue that represents a low risk of predation. Moreover, a previous study in Europe showed that past ecological conditions are better predictors of the distribution of Barn Swallows than that by the current ecological conditions (Ambrosini et al. 2002b). Although study sites differ, it is likely that swallows select their breeding sites based on reliable cues that provide information from prior years, and, thus, their distribution is related to the conditions of past breeding sites.

The use of indirect social cues for breeding-site selection reduces the costs associated with trial and error learning (Danchin et al. 2004). Additionally, breeding performance is higher in individuals using indirect socials cues than those using environmental cues (Boulinier and Danchin 1997). Social factors integrate the effects of environmental factors on breeding-site selection (Doligez et al. 2003). Moreover, indirect social cues are assumed as useful when birds have limited time for habitat sampling because of the seasonal constraints of breeding (Boulinier and Danchin 1997; Valone and Templeton 2002). Since swallows are migratory birds, they likely have limited habitat-sampling opportunities. Therefore, they may use indirect social cues as reliable cues for breeding-site selection.

In conclusion, the findings of this study show that breeding-site selection in Barn Swallows is based on the cue of undamaged old nests and that nest sites surrounded by undamaged old nests are preferred breeding sites. This investigation is one of the few studies that simultaneously analyzed the relative effects of resource and social cues on breeding-site selection (Müller et al. 2005; Betts et al. 2008a). This study shows the importance of an indirect social cue in the process of breeding site selection in migratory birds. Furthermore, we show that factors affecting breeding-site selection may vary at different spatial scales. Although the nest-site characteristics related to predation did not affect the analysis in terms of predator activity (Schmidt et al. 2006) and memories (Sonerud 1993), swallows might cue on nest-site characteristics in hierarchical breeding-site selection strategies. Further analysis is required to examine whether swallows use a combination of undamaged old nests and nest-site characteristics as cues at different spatial scales.

References

Aebischer A, Perrin N, Krieg M, Studer J, Meyer DR (1996) The role of territory choice, mate choice and arrival date on breeding success in the Savi’s warbler Locustella luscinioides. J Avian Biol 27:143–152

Ambrosini R, Saino N (2010) Environmental effects at two nested spatial scales on habitat choice and breeding performance of barn swallow. Evol Ecol 24:491–508

Ambrosini R, Bolzern AM, Canova L, Arieni S, Møller AP, Saino N (2002a) The distribution and colony size of barn swallows in relation to agricultural land use. J Appl Ecol 39:524–534

Ambrosini R, Bolzern AM, Canova L, Saino N (2002b) Latency in response of barn swallow Hirundo rustica populations to changes in breeding habitat conditions. Ecol Lett 5:640–647

Balbontin J, Møller AP, Hermosell IG, Marzal A, Reviriego M, De Lope F (2009) Individual responses in spring arrival date to ecological conditions during winter and migration in a migratory bird. J Anim Ecol 78:9819–9989

Barclay RMR (1988) Variation in the costs, benefits, and frequency of nest reuse by barn swallows (Hirundo rustica). Auk 105:53–60

Betts MG, Rodenhouse NL, Sillett TS, Doran PJ, Holmes RT (2008a) Dynamic occupancy models reveal within-breeding season movement up a habitat quality gradient by a migratory songbird. Ecography 31:592–600

Betts MG, Hadley AS, Rodenhouse N, Nocera JJ (2008b) Social information trumps vegetation structure in breeding-site selection by a migrant songbird. Proc R Soc Lond B 275:2257–2263

Boulinier T, Danchin E (1997) The use of conspecific reproductive success for breeding patch selection in territorial migratory species. Evol Ecol 11:505–517

Bowerman BL, O’Connell RT (1990) Linear statistical models: an applied approach, 2nd edn. Duxbury, Belmont

Cavitt JF, Pearse AT, Miller TA (1999) Brown Thrasher nest reuse: a time saving resource, protection from search-strategy predators, or cues for nest-site selection? Condor 101:859–862

Chalfoun AD, Martin TE (2007) Assessments of habitat preferences and quality depend on spatial scale and metrics of fitness. J Appl Ecol 44:983–992

Currie D, Thompson DBA, Burke T (2000) Patterns of territory settlement and consequences for breeding success in the Northern Wheatear Oenanthe oenanthe. Ibis 142:389–398

Dale S, Steifetten O, Osiejuk TS, Losak K, Cygan JP (2006) How do birds search for breeding areas at the landscape level? Interpatch movements of male Ortolan buntings. Ecography 29:886–898

Dall SRX, Giraldeau LA, Olsson O, McNamara JM, Stephens DW (2005) Information and its use by animals in evolutionary ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 20:187–192

Danchin E, Giraldeau LA, Valone TJ, Wagner RH (2004) Public information: from nosy neighbors to cultural evolution. Science 305:487–491

Doligez B, Cadet C, Danchin E, Boulinier T (2003) When to use public information for breeding habitat selection? The role of environmental predictability and density dependence. Anim Behav 66:973–988

Eggers S, Griesser M, Nystrand M, Ekman J (2006) Predation risk induces changes in nest-site selection and clutch size in the Siberian jay. Proc R Soc Lond B 273:701–706

Fontaine JJ, Martin TE (2006) Habitat selection responses of parents to offspring predation risk: an experimental test. Am Nat 168:811–818

Forsman JT, Hjernquist MB, Taipale J, Gustafsson L (2008) Competitor density cues for habitat quality facilitating habitat selection and investment decisions. Behav Ecol 19:539–545

Fujita G (1993) Nest site selection and reproductive success in barn swallows. Strix 12:35–39 (in Japanese)

Helfenstein F, Wagner RH, Danchin E, Rossi JM (2003) Functions of courtship feeding in black-legged kittiwakes: natural and sexual selection. Anim Behav 65:1027–1033

Jones J (2001) Habitat selection studies in avian ecology: a critical review. Auk 118:557–562

Lima SL (2009) Predators and the breeding bird: behavioral and reproductive flexibility under the risk of predation. Biol Rev 84:485–513

Martin TE (1993) Nest predation and nest sites-new perspectives on old patterns. Bioscience 43:523–532

Martin TE (1998) Are microhabitat preferences of coexisting species under selection and adaptive? Ecology 79:656–670

Møller AP (1987) Advantages and disadvantages of coloniality in the swallow Hirundo rustica. Anim Behav 35:819–823

Møller AP (1990) Effects of parasitism by a haematophagous mite on reproduction in the barn swallow. Ecology 71:2345–2357

Møller AP (1994) Sexual selection and the barn swallow. Oxford University Press, New York

Møller AP (2010) The fitness benefit of association with humans: elevated success of birds breeding indoors. Behav Ecol 21:913–918

Montgomery DC, Peck EA (1982) Introduction to linear regression analysis. Wiley, New York

Müller M, Pasinelli G, Schiegg K, Spaar R, Jenni L (2005) Ecological and social effects on reproduction and local recruitment in the red-backed shrike. Oecologia 143:37–50

Parejo D, White J, Danchin E (2007) Settlement decisions in Blue tits: difference in the use of social information according to age and individual success. Naturwissenschaften 94:749–757

Pärt T, Doligez B (2003) Gathering public information for habitat selection: prospecting birds cue on parental activity. Proc R Soc Lond B 270:1809–1813

Pulliam HR (1988) Sources, sinks, and population regulation. Am Nat 132:652–661

Robertson BA, Hutto RL (2006) A framework for understanding ecological traps and an evaluation of existing evidence. Ecology 87:1075–1085

Safran RJ (2004) Adaptive site selection rules and variation in group size of Barn swallows: individual decisions predict population patterns. Am Nat 164:121–131

Schlaepfer MA, Runge MC, Sherman PW (2002) Ecological and evolutionary traps. Trends Ecol Evol 17:474–480

Schmidt KA, Ostfeld RS, Smyth KN (2006) Spatial heterogeneity in predator activity, nest survivorship, and nest-site selection in two forest thrushes. Oecologia 148:22–29

Sonerud GA (1993) Reduced predation by nest box relocation: differential effect on Tengmalm’s Owl nests and artificial nests. Ornis Scand 24:249–253

Turner A, Rose C (1989) Swallows and martins. Christopher Helm, London

Valone TJ, Templeton JJ (2002) Public information for the assessment of quality: a widespread social phenomenon. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 357:1549–1557

Visser ME, Holleman LJM, Caro SP (2009) Temperature has a causal effect on avian timing of reproduction. Proc R Soc Lond B 276:2323–2331

Acknowledgments

We thank Go Fujita for helpful advice about the field study and comments about the manuscript. We also thank Masami Hasegawa and Takeshi Kitamura for facilitating the fieldwork, and the local residents in the study area for their cooperation. The study complied with the current Japanese Law and was permitted by the Ministry of the Environment.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by F. Bairlein.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ringhofer, M., Hasegawa, T. Social cues are preferred over resource cues for breeding-site selection in Barn Swallows. J Ornithol 155, 531–538 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-013-1035-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-013-1035-3