Abstract

Dutch farmland bird populations are in steep decline as a result of agricultural intensification. The Yellow Wagtail (Motacilla flava flava) is one of those species, but its decrease has mainly occurred in grasslands, with its population in arable areas remaining more or less stable. In contrast, populations of other typical birds of arable habitats, such as the Skylark (Alauda arvensis) and Grey Partridge (Perdix perdix), are declining strongly in this habitat type. The favorable status of the Yellow Wagtail is probably caused by the crop-mosaic composition of arable farms in The Netherlands, which often includes winter cereals, potatoes, and sugar beet. This study focused on crop preference by the Yellow Wagtail during the breeding season. Early in the breeding season Yellow Wagtails showed a strong preference for winter cereals. However, as the breeding season progressed, their preference gradually shifted to broad-leaved crops, especially potatoes. Measurements of the crop structure as an indication for vegetation height or bare ground, revealed that the Yellow Wagtail strongly preferred crops 20–40 cm high. Higher crops were also used more than expected based on a uniform distribution, but to a lesser extent, and crops <20 cm in heigth were not preferred at all. In terms of ground coverage, Yellow Wagtails preferred crops providing a ground coverage of at least 60%. There was a negative association between Yellow Wagtail numbers and crops providing <20% ground coverage.

Zusammenfassung

Durch die Intensivierung der Landwirtschaft gehen die Bestände niederländischer Feldvogelarten stark zurück. Die Schafstelze (Motacilla flava flava) gehört zu diesen Arten, aber ihr Rückgang erfolgte hauptsächlich im Grasland, während die Population im Ackerland relativ stabil blieb. Im Gegensatz dazu gingen dort Populationen anderer typischer Feldvögel, wie Feldlerche (Alauda arvensis) und Rebhuhn (Perdix perdix), stark zurück. Die günstige Lage der Schafstelze auf niederländischen Farmen ist wahrscheinlich auf die Zusammensetzung der Feldfrüchte zurückzuführen, die oft aus Wintergetreide, Kartoffeln und Zuckerrüben bestehen. Diese Studie beschäftigt sich mit der Habitatwahl der Schafstelze in der Brutsaison. Zu Beginn der Brutsaison bevorzugte die Schafstelze Wintergetreide. Später verschob sich diese Präferenz jedoch zugunsten breitblättriger Anbaupflanzen, vor allem Kartoffeln. Um Vorlieben für bestimmte Vegetationshöhen oder bloßen Erdboden zu untersuchen, wurde die Struktur der Anbauflächen erfasst. Schafstelzen zeigten eine starke Vorliebe für Pflanzen mit einer Höhe von 20–40 cm. Höhere Pflanzen wurden auch mehr genutzt, als eine Gleichverteilung vermuten ließe, aber weniger als Pflanzen in der 20–40 cm Höhenklasse. Pflanzen von weniger als 20 cm wurden weniger genutzt. Überdies bevorzugten Schafstelzen Anbaupflanzen mit mindestens 60% Bodendeckung. Es gab einen negativen Zusammenhang zwischen dem Vorkommen von Schafstelzen und Anbaupflanzen mit weniger als 20% Bodendeckung.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Agricultural intensification has resulted in steep declines of farmland bird populations in Europe (e.g., Donald et al. 2001). The Netherlands is one of the most intensively farmed countries in the world, and many farmland bird species have been placed on the national Red List (van Beusekom et al. 2005). Declining bird populations have been observed in both grassland areas and arable areas, with some species, such as the Skylark (Alauda arvensis) experiencing similar declines in both habitat types. Other species, however, are showing a much stronger decline in grassland areas than in arable areas. One such example is the Yellow Wagtail (Motacilla flava flava): its population is relatively stable in Dutch arable landscapes (Provincie Groningen 2003) where it is one of the most common birds found in arable fields, reaching densities of 15–20 breeding pairs per 100 ha (Kragten and de Snoo 2008).

In current arable farming systems, several factors have been identified to be responsible for the declines in farmland bird populations (Robinson and Sutherland 2002). Suitable breeding habitat has been limited by farm specialization, increased field size, and the shift from spring to winter cereals (Chamberlain et al. 2000). Additionally, high inputs of pesticides and artificial fertilizers have limited food availability (Chamberlain et al. 2000; Stoate et al. 2009). Finally, as a result of more efficient harvesting methods and the disappearing of cereal stubble fields in winter, food availability for wintering birds is low and winter mortality rates have increased (e.g., Siriwardena et al. 2008). For long-distance migrating species, such as the Yellow Wagtail and Black-tailed Godwit (Limosa limosa), changing conditions in wintering areas also negatively impact on breeding population sizes (Zwarts et al. 2009).

Ground-nesting farmland passerines, such as the Skylark and Yellow Wagtail, need multiple broods within a single breeding season to produce sufficient offspring to maintain population levels (e.g., Wilson et al. 1997). However, studies on the Skylarks have shown that the possibilities for multiple breeding attempts in modern arable landscapes are often limited (Wilson et al. 1997; Kragten et al. 2008). Skylarks prefer spring cereals as a breeding habitat, and the switch from spring cereals towards winter cereals is likely one of the main causes of declines in Skylark populations (Donald 2004). In contrast to the Skylarks, the British Yellow Wagtail (Motacilla flava flavissima) seems to prefer winter cereals and potatoes as a breeding habitat (Gilroy et al. 2009a). As these crops are the two most dominant crops in arable farming systems in The Netherlands, this preference may explain the stable population of Yellow Wagtails on Dutch arable fields.

The study reported here was designed to assess crop preference by breeding populations of Yellow Wagtails in an intensively used arable landscape in order to develop a better understanding of why these birds are still relatively common in Dutch arable fields. The study also focused on how crop preference changes during the breeding season. The results of this study could lead to recommendations for improving agri-environment schemes.

Methods

Study area

This study was carried out on two polders in the province of Flevoland, The Netherlands: Oostelijk Flevoland and the Noordoostpolder. These polders were reclaimed during the 1950s and 1930s, respectively, and were designed for optimal agricultural production. Both polders have a similar homogenous landscape characterized by rectangular parcels of approximately 22 (Noordoostpolder) and 30 (Oostelijk Flevoland) ha. Soil type is clay of marine origin. Most parcels are bordered by ditches and larger waterways. The landscape is very open, and the only tree lines are along roads; at several locations there are operational wind turbines. Land use is mainly agricultural and predominantly arable farming. Dominant crops are potatoes, winter cereals, sugar beet, and onions. On average, about 3–4% of the farm area consists of non-crop habitats, mainly grassy field margins and ditch banks. Fields are generally ploughed in the autumn, with no stubble being left in the winter. Pesticide use by farmers on these polders is comparable to that in other Dutch arable regions (de Snoo and de Jong 1999).

Data collection and analysis

The study was carried out on ten and 20 conventionally managed arable farms during the spring of 2004 and 2005, respectively. All farms investigated in 2004 were investigated once again in 2005. Mean farm size was about 40 ha. In 2004, a total area of 392 ha was investigated; in 2005, 816 ha. Mean territory density (±standard deviation) per 100 ha in each year was 20.1 ± 11.4 and 14.1 ± 12.6, respectively. Dominant crops were potatoes, sugar beet, winter cereals, and onions. An overview of crops grown on the farms and their relative acreage is given in Table 1.

The standard method of the Dutch Breeding Bird Monitoring Project was employed to assess the presence of breeding Yellow Wagtails (van Dijk 2004). Farms were visited on five occasions between April and July, with each visit beginning 30 min before sunrise and lasting until 3 h after sunrise. Birds were mapped while walking transects along the field edges, with only those birds showing behaviour indicating breeding recorded. The following behaviour categories were considered as indicating breeding activity: (1) singing males, (2) displaying males, (3) territorial conflicts between birds, (4) birds carrying nest material, (5) alarming birds, and (6) birds carrying food. Yellow Wagtail pairs present between April 15 and July 20 or individual birds present between June 1 and July 20 were also considered to be breeding. These dates are comparable to those of van Dijk (2004).

In addition to the bird surveys, crop height (centimeters) and ground coverage (percentage) were also determined for each crop. This occurred on the same days as the bird surveys took place, with the measurements made at randomly chosen fixed points that were a minimum distance of 25 m from the field edge. Mean crop height was determined using a measuring stick; ground coverage was determined by visual estimation at the same location as where the crop height was determined.

In order to assess crop preference by breeding Yellow Wagtails, all farms were considered to be one study area within which the birds could select their breeding habitat. This design was chosen because most crops were not grown by all farmers. The observed number of territorial Yellow Wagtails was then compared with the expected values based on a uniform territory distribution over different crop types. This calculation was made for all five visits on which breeding birds were counted. Using this approach, it was possible to analyze and identify crop preference in terms of different periods of the breeding season and shifts in crop preference.

To obtain more insight in the effects of crop height and ground coverage on the presence of Yellow Wagtails, all records of Yellow Wagtails indicating breeding activity were assigned to categories of crop height and ground coverage. For crop height, the following categories were applied: 0–20, 21–40, 41–0, 61–80, 81–100, and >100 cm. Ground coverage was expressed as the percentage of soil covered with green vegetation; the categories used were: 0–20, 21–40, 41–60, 61–80, and 81–100%. For the dominating crop types (winter cereals, potatoes, sugar beet and onions) also, the presence of Yellow Wagtails was related to crop structure using these categories.

Results

Shift in crop preference

Basically, a similar pattern of crop preference was found in both years. Yellow Wagtails showed a preference for winter cereals during the entire breeding season, but the preference for this crop type decreased as the breeding season progressed (Table 2). Territorial Yellow Wagtails were mainly found among winter cereals, especially during the first part of the breeding season. In 2004, this was the case until approximately mid May, but in 2005 this lasted until mid June (Fig. 1). In this period, relative Yellow Wagtail numbers were high in territories with winter cereals, varying from 37 to 60%, which was much higher than the number of territories expected based on a uniform distribution (Table 2). Although the relative numbers of Yellow Wagtails decreased in territories with winter cereals as the breeding season progressed, this crop type was still relatively important to the birds (19–33% of the records). Potatoes were only preferred during the second half of the breeding season, with the preference for this crop increasing towards the end of the breeding season: at the end of the breeding season the majority of Yellow Wagtails were to be found in this crop type (40–51%). The other two dominant crop types in The Netherlands, sugar beet and onions, were not preferred by Yellow Wagtails. At the beginning of the breeding season, Yellow Wagtails were hardly recorded in sugar beet fields at all (0–4%), but as the breeding season progressed, the number of Yellow Wagtails in sugar beet fields increased to 7–16%. Compared to winter cereals and potatoes, these numbers are relatively low, but on a similar level as what could be expected under a uniform distribution. The presence of Yellow Wagtails in onion fields was also low, decreasing as the breeding season progressed from 10–13% to 0–6%. In 2005, Yellow Wagtails seemed to have a weak preference for onion fields at the beginning of the breeding season, but thereafter there was a distinct negative association between Yellow Wagtails and onion fields. Of the minor crops, only tulips seemed to be of importance to Yellow Wagtails. Early in the breeding season, this crop type attracted up to 30% of the territorial birds, even though it covered only 0.5% of the total study area. As the season progressed, the number of birds in this crop remained more or less equal, while numbers in other crop types increased.

Preference for crop height and ground coverage

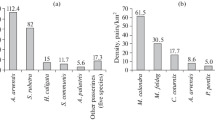

Figure 2 shows the preference of Yellow Wagtails for crops of a certain height. During the whole breeding season there was a preference for crops 20–40 cm in height; Yellow Wagtails also showed a preference for crops taller than this, but to a lesser extent. During the first two sampling periods, Yellow Wagtails showed a relatively strong preference for crops of 60–80 cm in height, of which the main constituents were winter cereals. Crops <20 cm in height were used less than expected in comparison to a uniform use of the area.

Preference of territorial Yellow Wagtails for certain crop heights. y-axis Preference by birds based on the difference between observed numbers of birds and expected numbers in a uniform distribution. Positive values indicate a preference, negative values indicate avoidance. Categories of crop height (in centimeters) are indicated on the x-axis. Periods represent sampling periods: 1 April 15–April 30, 2 May 1–May 15, 3 May 16–May 31, 4 June 1–June 15, 5 June 15–June 30

For the winter cereals, most Yellow Wagtails were recorded when the crop was 60–100 cm high (70%); 18% of observations were recorded in winter cereals 20–60 cm in height and 12% of observations were recorded in crops >100 cm. In potatoes, 63% of the observations were recorded when the crop was 20–40 cm high; other records of Yellow Wagtails were made when the crop was <20 cm (15%), between 40 and 60 cm (18%), or >60 cm (3%). In sugar beet fields, Yellow Wagtails were mostly recorded when the crop was 20–40 cm high (75%), with 13% of records made when the crop was <20 cm in height, which was also the case when the crop was 40–60 cm high. For onions, 66% of the records was made in fields when the crop was 0–20 cm high and 33% in fields where the crop was 20–40 cm high. These results indicate that mainly high cereals are used as breeding habitat by Yellow Wagtails, while broad-leaved crops, such as potatoes and sugar beet, are suitable when they are 20–40 cm high.

Figure 3 shows the preference of Yellow Wagtail for different categories of ground coverage. In general, there were positive associations between Yellow Wagtail presence and a ground coverage of >60%. Yellow Wagtails especially preferred crops with a ground coverage of >80%. Relatively strong negative associations were found with crops having a ground coverage of <20%.

Preference of territorial Yellow Wagtails for crops with a certain ground coverage. y-axis Preference by birds based on the difference between observed numbers of birds and expected numbers in a uniform distribution. Positive values indicate a preference, negative values indicate avoidance. x-axis Categories of ground coverage (%). Periods represent sampling periods: 1 April 15–April 30, 2 May 1–May 15, 3 May 16–May 31, 4 June 1–June 15, 5 June 15–June 30

All records of Yellow Wagtails in winter cereals were made when ground coverage was between 80 and 100%. In potatoes, 73% of the records were made when ground coverage was >60%. Other records were only made in crops with a ground coverage of <40%. The pattern for sugar beet was similar to that for potatoes. In total, 81% of the records were made when ground coverage was >60%. Other records were made in sugar beet fields with a ground coverage of between 20 and 40%. In contrast, most Yellow Wagtails (83%) in onions were recorded when the ground coverage was <20%. Only 17% of all records were made in onion fields with a ground coverage of between 60 and 80%. These results strongly indicate that Yellow Wagtails prefer dense crop types that provide sufficient cover.

Discussion

In general, small passerine birds need multiple broods to produce sufficient offspring to maintain population levels. Ground-nesting farmland passerines, such as the Yellow Wagtail and Skylark often nest within arable crops. Cover provided by these crops determines whether a crop is suitable as a nesting site. However, as crops grow, the crop structure changes and, consequently, so does the suitability of a crop as nesting site. Therefore, ground-nesting birds likely require a mosaic of crops that provide suitable conditions throughout the entire breeding season. The results of this study showed that, especially during the first part of the breeding season, Yellow Wagtails have a strong preference for winter cereals. As the breeding season progresses, other crops, potatoes in particular, are also used more frequently. These findings are similar those reported in the UK (Gilroy et al. 2009a) and indicate that an ideal crop mosaic for Yellow Wagtails should at least consist of winter cereals and potatoes. These are the two dominate crops on the intensive arable farms of The Netherlands and likely account for the densities of Yellow Wagtails tending to be higher on conventional arable farms than on organic arable farms (Kragten and de Snoo 2008). Another factor to be considered is that on organically managed farms the availability of winter cereals is very limited, and there are not many other crops providing enough cover early in the breeding season (Kragten et al. 2008).

It was evident from our records that Yellow Wagtails especially preferred winter cereals during the first period (April 15–May 15) of the breeding season. Two factors may account for this preference: (1) winter cereals were one of the few crops providing sufficient cover during this period; (2) winter cereals were available in relatively large areas at the study sites. High numbers of Yellow Wagtails were also present in tulip fields during this period. Tulips provide cover as early as the beginning of April (crop height 20–40 cm, ground coverage approx. 80%). Other dominant crops, such as potatoes, sugar beet, and onions, are all spring sown crops and therefore provide only little cover during the first half of the breeding season. However, from more or less the end of May, the Yellow Wagtails showed a decreased preference for winter cereals and an increased preference for potatoes. Their numbers also increased in sugar beet fields during this time, but to a lesser extent compared to the potato fields. The decrease in a preference for winter cereal fields is probably a result of the crop becoming too high and dense as the breeding season progresses. Skylarks have also been found to have this same changing preference (e.g. Donald 2004; Kragten et al. 2008). However, during the second half of the breeding season, broad-leaved crops, such as potato and sugar beet, still provide sufficient cover, possibly explaining the partial shift from winter cereals to these crop types.

It remains unclear whether crop height or ground coverage is the best factor accounting for Yellow Wagtail abundance. Yellow Wagtails partly feed on ground-dwelling invertebrates, which supports ground coverage as the most determining factor. However, in onion fields, most of the observations of Yellow Wagtails were recorded in fields with little ground coverage, although this could only mean that food is easily available there and that these fields are possibly mainly used as only feeding sites. Crop structures can be very different between crops. Potato fields might provide a high percentage of ground coverage, but birds still have access to the ground to forage, while this is much less the case for a dense cereal crop with a similar amount of ground coverage. In addition, small open patches, such as tramlines, can be used as foraging sites (Poulsen et al. 1998). Thus, dense crops can still provide sufficient foraging opportunities.

Another explanation for the shift in crop preference by Yellow Wagtails during the breeding season may be linked with food availability. Kragten et al. (2010) investigated invertebrate abundance on the same farms which were used in this study. During this study, invertebrates were sampled during the first week of June among the most dominant crops of the farms, including winter cereals and potatoes. Total invertebrate abundance did not differ between the two crop types, but the abundance of Diptera was more than sevenfold higher in potato fields. Diptera are known to be an important prey item for Yellow Wagtails (Holland et al. 2006) and therefore this abundance also have played a role in the increased use of potato fields during the second half of the breeding season.

Although the preference for winter cereals decreased during the second half of the breeding season, Yellow Wagtails were still frequently recorded in fields of this crop type, possibly indicating that some Yellow Wagtails also make their second nest in winter cereals. The second or third nests of Skylarks built in winter cereal fields are often located close to tramlines, where access to the ground is easier. Consequently, these nests suffer high predation rates as many ground predators use these tramlines to cross fields (Donald 2004). Therefore, more detailed studies are needed that focus on the breeding success of Yellow Wagtails in large scale arable habitats.

The author would like to draw the reader’s attention to the fact that the results reported here are based on records of birds showing breeding or territorial behaviour. The location of the nest may be in a different field than where the bird was spotted. However, based on similar results found in other studies (e.g., Gilroy et al. 2009a, b), this bias is probably limited.

As winter cereals and potatoes are dominating crops in Dutch arable landscapes, the crop preference of the Yellow Wagtail as described in this study could provide an explanation for the stable population development of this species compared to other ground-nesting birds of arable fields (Provincie Groningen 2003). For other species, such as the Skylark, the current crop mosaic in Dutch arable landscapes does not provide a suitable habitat during the peak of the breeding season (Kragten et al. 2008), which likely explains, at least partially, the strong decline of Skylark populations in arable habitats (Provincie Groningen 2003). However, ensuring a crop mosaic that provides suitable nesting sites during the entire breeding season is only one aspect of conserving ground-nesting farmland passerines. There must also be sufficient food available to assure adult and chick survival. As Yellow Wagtails are insectivorous birds (Smith 1950; Gilroy et al. 2009b), they need insect-rich habitats to survive. Grassy or herbaceous field margins generally contain high numbers of invertebrates (Marshall and Moonen 2002). These margins are frequently used by birds, and there are indications that this use results in chicks with a better body condition (Teunissen et al. 2009). Wet ditches and tracks are also often used as foraging habitats (Gilroy et al. 2009b). In addition, unsprayed crop edges are also known to be attractive foraging habitats for Yellow Wagtails (de Snoo et al. 1994). Finally, Yellow Wagtails frequently forage in the same fields that are used for nesting (Gilroy et al. 2009b). Several studies have shown that invertebrate abundance is higher on organically managed fields (i.e., fields that lack inputs of chemical pesticides and artificial fertilizers) than on conventionally managed fields (e.g., Hole et al. 2005; Kragten et al. 2010). Consequently, organic farm management could have positive effects on the breeding success of Yellow Wagtails.

In most European countries agri-environment schemes for arable fields focus on field margin management or on the implementation of set-aside plots. However, most ground-nesting birds of arable fields use the area covered by crops as nesting sites. Field margin management is particularly aimed at creating insect-rich habitats for birds, but field margins generally do not provide a suitable nesting habitat. Therefore, future agri-environment schemes should also focus on creating crop mosaics which provide suitable nesting sites throughout the entire breeding season. By adopting such an approach, management programs increase the chance that ground-breeding farmland passerines will be able to produce a sufficient number of broods to maintain sustainable population levels.

References

Chamberlain DE, Fuller RJ, Bunce RGH, Duckworth JC, Shrubb M (2000) Changes in the abundance of farmland birds in relation to the timing of agricultural intensification in England and Wales. J Appl Ecol 37:771–788

de Snoo GR, de Jong FMW (1999) Bestrijdingsmiddelen en Milieu. Jan van Arkel, Utrecht

de Snoo GR, Dobbelstein RTJM, Koelwijn S (1994) Effects of unsprayed crop edges on farmland birds. BCPC Monogr 58:221–226

Donald PF (2004) The skylark. T & AD Poyser, London

Donald PF, Green RE, Heath MF (2001) Agricultural intensification and the collapse of Europe’s farmland bird populations. Proc R Soc B 268:25–29

Gilroy JJ, Anderson GQA, Grice PV, Vickery JA, Sutherland WJ (2009a) Mid-season shifts in the habitat association of Yellow Wagtails Motacilla flava breeding in arable farmland. Ibis 152:90–104

Gilroy JJ, Anderson GQA, Grice PV, Vickery JA, Watts N, Sutherland WJ (2009b) Foraging habitat selection, diet and nestling condition in Yellow Wagtails Motacilla flava breeding on arable farmland. Bird Study 56:221–232

Hole DG, Perkins AJ, Wilson JD, Alexander IH, Grice PV, Evans AD (2005) Does organic farming benefit biodiversity? Biol Conserv 122:113–130

Holland JM, Hutchison MAS, Smith B, Aebischer NJ (2006). A review of invertebrates and seed-bearing plants as food for farmland birds in Europe. Ann Appl Biol 148:49–71

Kragten S, de Snoo GR (2008) Field-breeding birds on organic and conventional arable farms in The Netherlands. Agric Ecosyst Environ 126:270–274

Kragten S, Trimbos KB, de Snoo GR (2008) Breeding Skylarks on organic and conventional arable farms in The Netherlands: the effects of cropping pattern and crop management. Agric Ecosyst Environ 126:163–167

Kragten S, Tamis WLM, Gertenaar E, Midcap Ramiro SM, van der Poll RJ, Wang J, de Snoo GR (2010) Abundance of invertebrate prey for birds on organic and conventional arable farms in The Netherlands. Bird Conserv Int. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270910000079

Marshall EJP, Moonen AC (2002) Field margins in northern Europe: their functions and interactions with agriculture. Agric Ecosyst Environ 89:5–21

Poulsen JG, Sotherton NW, Aebischer NJ (1998). Comparative nesting and feeding ecology of skylarks Alauda arvensis in southern England with special reference to set-aside. J Appl Ecol 35:131–147

Provincie Groningen (2003) De toestand van natuur en landschap in de provincie Groningen 2002. Provincie Groningen, Groningen

Robinson RA, Sutherland WJ (2002) Post-war changes in arable farming and biodiversity in Great Britain. J Appl Ecol 39:157–176

Siriwardena GM, Calbrade NA, Vickery JA (2008) Farmland birds and late winter food: does seed supply fail to meet demand? Ibis 150:585–595

Smith SG (1950) The Yellow Wagtail. Collins, London

Stoate C, Báldi A, Beja P, Boatman ND, Herzon I, van Doorn A, de Snoo GR, Rakosy L, Ramwell C (2009) Ecological impacts of early 21st century agricultural change in Europe—a review. J Environ Manage 91:22–46

Teunissen W, Koks BJ, Kragten S, van ‘t Hoff J, Arisz J, Ottens HJ, Roodbergen M (2009) Conservation measures for breeding skylarks on arable land in The Netherlands. In: British Ornithologists’ Union (ed) Lowland farmland birds III: delivering solutions in an uncertain world (abstract). In: BOU 2009 annual conference. British Ornithologists’ Union, Sacramento

van Beusekom R, Huigen P, Hustings F, de Pater K, Thissen J (2005) Rode Lijst van de Nederlandse broedvogels. Tirion Uitgevers, Baarn

van Dijk AJ (2004) Handleiding Broedvogel monitoring project (Broedvogelinventarisatie in proefvlakken). SOVON Vogelonderzoek Nederland, Beek-Ubbergen

Wilson JD, Evans J, Browne SJ, King JR (1997) Territory distribution and breeding success of skylarks Alauda arvensis on organic and intensive farmland in southern England. J Appl Ecol 34:1462–1478

Zwarts L, Bijlsma RG, Kamp J vander, Wymenga E (2009). Living on the edge; wetlands and birds in a changing Sahel. KNNV Uitgeverij, Zeist

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to all of the farmers who allowed me to carry out bird surveys on their farms. Erwin Reinstra and Cathy Wiersema assisted with the field work. The comments of two anonymous reviewers significantly increased the quality of the paper. This study was financed by Leiden University.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by F. Bairlein.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kragten, S. Shift in crop preference during the breeding season by Yellow Wagtails Motacilla flava flava on arable farms in The Netherlands. J Ornithol 152, 751–757 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-011-0655-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-011-0655-8