Abstract

Objective

Phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (PC-MRI) is a non-invasive method used to compute blood flow velocity and volume. This systematic review aims to discuss the current status of renal PC-MRI and provide practical recommendations which could inform future clinical studies and its adoption in clinical practice.

Methodology

A comprehensive search of all the PC-MRI studies in human healthy subjects or patients related to the kidneys was performed.

Results

A total of 39 studies were included in which PC-MRI was used to measure renal blood flow (RBF) alongside other derivative hemodynamic parameters. PC-MRI generally showed good correlation with gold standard methods of RBF measurement, both in vitro and in vivo, and good reproducibility. Despite PC-MRI not being routinely used in clinical practice, there are several clinical studies showing its potential to support diagnosis and monitoring of renal diseases, in particular renovascular disease, chronic kidney disease and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

Discussion

Renal PC-MRI shows promise as a non-invasive technique to reliably measure RBF, both in healthy volunteers and in patients with renal disease. Future multicentric studies are needed to provide definitive normative ranges and to demonstrate the clinical potential of PC-MRI, likely as part of a multi-parametric renal MRI protocol.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The assessment of renal blood flow (RBF) is particularly important for the diagnosis and monitoring of renal diseases, including chronic and acute kidney diseases, renovascular disease, and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), because changes in RBF are prominent at the earliest stages of disease. Different techniques have been used to determine RBF in patients with renal disease; however, these techniques may be unacceptably invasive or unable to accurately measure RBF [1]. Color Doppler ultrasonography is easily accessible, but is user dependent, and it can be technically challenging to make accurate flow measurements in overweight patients. RBF can be estimated from para-aminohippurate (PAH) renal clearance. PAH is filtered freely at the glomerulus and secreted by the tubules so that it is almost completely removed from the blood that passes through the kidneys. Therefore, the rate at which the kidneys can clear PAH (measured during a continuous infusion) reflects total renal plasma flow. However, the renal extraction rate of PAH is not 100%, meaning that the calculated ‘effective renal plasma flow’ (ERPF) tends to underestimate the true renal plasma flow. Renal extraction of PAH is usually assumed to be 85% in healthy subjects [2, 3], but can go down to 70% in patients with renal impairment [2], and the individual reduction in PAH clearance is rather unpredictable [4]. Since ERPF is calculated by dividing PAH clearance by PAH renal extraction ratio, the variability of the latter is a potential source of error [5] reducing the accuracy of the method. Phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (PC-MRI) is a MRI technique for determining blood flow velocity and volume in a specific vessel during the cardiac cycle. PC-MRI is already used in mainstream clinical practice in cardiology and has been extensively validated [6]. It is also reliably used in newborns [7] whose vessel size can be similar to adult renal vessels. PC-MRI, with no need for contrast agents potentially associated with risks for renal patients, provides a non-invasive alternative to measure RBF in patients.

The present article aims to systematically review all the existing literature on renal PC-MRI in healthy volunteers and patients with renal disease, to discuss the current status of renal PC-MRI as an imaging biomarker, and to provide practical recommendations which could inform future clinical studies and renal PC-MRI adoption in clinical practice.

Methodology (inclusion and exclusion criteria)

A comprehensive search of all the PC-MRI studies in human subjects or patients related to the kidneys, excluding animal experiments, and reporting renal blood flow velocity or volume, was performed on 31 March 2019 using PubMed, and crossed checked with references cited by the related publications. Search terms are available as Online Resource (supplementary material, Section S2). A total of 54 hits were found, identifying 39 papers meeting the inclusion criteria. All the human studies involving renal PC-MRI and reporting RBF values have been summarized in tables and are available as Online Resource (see Supplementary review table).

PC-MRI acquisition and analysis

PC-MRI acquisition methods

PC-MRI technique is based on applying magnetic gradients such that the signal phase is made sensitive to the velocity of moving tissue or blood. This is obtained by insertion of a bipolar gradient pair between excitation and signal read-out. The velocity or flow sensitivity of the sequence is defined by the velocity encoding (Venc) parameter, which can be modified by varying the amplitude and duration of the bipolar gradient pair, and can be computed using the following formula:

where \(\Delta \phi\) represents the phase difference. As signal phase is only unique between – \(\pi\) and \(+ \pi\), this corresponds to velocities being unique from – Venc to + Venc [8]. The obtained signal phase is carried over into the phase of the complex reconstructed images, and therefore, after reconstruction, two sets of images exist: the magnitude images and the velocity maps, which are the phase images.

The renal PC-MRI sequence is usually based on a 2D spoiled gradient echo pulse sequence with short repetition time (TR) and low flip angle. In general, TR and echo time (TE) should be the shortest possible to allow faster imaging and less flow induced artifacts. On a modern scanner, TE is usually below 6 ms, and TR is shorter that 13 ms. The flip angle should be low to allow rapid imaging, but is often slightly higher than the optimal flip angle, to increase inflow enhancement. Usually, in renal PC-MRI, flip angles between 10° and 30° are used. Since measurement of RBF is most commonly performed in arteries, ECG synchronization is normally applied. This can be performed either by prospective triggering or retrospective gating. The retrospective method, for which data are sampled continuously and sorted during reconstruction using the acquired ECG signal, is most commonly used currently. There have been attempts to measure renal artery flow without ECG gating [9, 10], which is faster and allows for breath-holding, but this reduces the spatial resolution or temporal sampling, degrading the accuracy and repeatability of RBF measurements [9].

PC-MRI scans are acquired as multi-phase or cine images, where a number of temporal frames during the cardiac cycle are acquired. The obtainable number of frames is inversely related to total scan time, because the number of sampled k-lines per frame (the turbo-factor) determines the duration for each frame. The number of frames used in renal artery blood flow measurements ranges from 15 to 80, but typically 20–30 frames are used. As flow measurements are based on the signal phase, the method is quite sensitive to \({B}_{0}\) inhomogeneity. Therefore, two segments with different velocity sensitivity are needed. These are acquired after each other, reducing the temporal resolution or increasing total scan time. The resulting velocity images are based on subtraction of the phase images from the two segments. Due to eddy-current effects and concomitant gradient fields, there might still be offset artifacts in the velocity images, i.e., zero velocity is not shown as zero. This can be corrected during post-processing by fitting a background plane to stationary regions [11]. This is still sometimes applied, but modern scanners have integrated correction methods for this error, and, therefore, offset correction should no longer be necessary [12]. When measuring blood flow in vessels which are moving significantly with respiration, such as the renal vessels, respiration control is often used. Three different strategies can be followed: making the imaging sequence so short (< 15 s) that breath-holding can be used [13]; using respiration gating [14, 15]; or making the scan time duration sufficiently long that motion-induced artifacts will partially be averaged out [16]. All three strategies have been successfully applied. The scan time for measuring in one artery, therefore, varies between 15 s [13] and 15 min [17]. Since a number of different functional MRI measurements are often included alongside PC-MRI, the scan time for the PC sequence should be kept below a few minutes. The spatial resolution needed for obtaining reasonably accurate mean flow values in vessels does not need to be too high. It has been shown that having just three pixels across the vessel diameter provides accurate blood volume flow rates [18]. With a renal artery diameter of about 5 mm, an acquired pixel size of about 1.5 mm should be sufficient. However, using a low spatial resolution may complicate the identification of the vessels during analysis, and, therefore, better spatial resolution is recommended, if possible. Typically pixel sizes between 1.0 and 1.5 mm have been used, and slice thickness of between 4 and 8 mm. Larger slice thickness would improve the signal-to-noise ratio, but at the risk of partial volume errors [19].

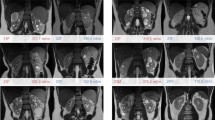

In 2D PC-MRI, the orientation of the measurement slice should be perpendicular to the vessel direction, as only the through-plane velocity component is usually acquired (Fig. 1). For measurements in renal arteries, a good survey image, such as an angiography scan, is, therefore, strongly recommended for clear depiction of the arteries, and also to ensure that the plane is positioned prior to any bifurcations of the artery. Novel PC-MRI acquisition methods, such as the 4D flow [3D Cine PC MR angiography (MRA)] technique, make the quantification of blood flow in three dimensions possible, even during free breathing [20, 21]. The main advantage of 3D PC-MRI over 2D PC-MRI is that the former allows extracting blood velocity and flow information on any plane, rather than in a single double oblique 2D slice. Renal flow measurements can be acquired on both 1.5 T and 3.0 T MR scanners. Both field strengths are being used, and there is no clear conclusion to which is preferable. Higher field strength will add to the signal-to-noise ratio, but artifacts, such as offset errors, might worsen. In most articles, the applied Venc is around 100 cm/s. It should be higher than the peak velocity to avoid aliasing, but not much higher as this will compromise the signal-to-noise ratio. Please refer to Table 1 for a summary of practical recommendations.

Schematic representation of phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (PC-MRI) acquisition and processing. a Prescription of PC-MRI of the right renal artery with acquisition plane perpendicular to the vessel direction. b Acquired coronal oblique magnitude (left) and velocity (right) images, with renal artery highlighted. c Profile of renal artery blood flow (RABF) in the acquisition plane defined in a. d 3D reconstruction showing average RABF computed in the right renal artery

In principle, RBF can be assessed in either renal arteries or renal veins, and the results should be comparable. However, renal vein blood flow has been measured only in a few papers [13, 19]. Measuring blood flow in the renal arteries is generally preferred, because they are easier to locate and the measurement planes are easier to position correctly. Alternatively, blood flow can be measured in the abdominal aorta before and after giving rise to renal arteries (inflow and outflow), with total RBF computed from the difference between the two aortic flows [22], based on the assumption that the inflow value should be equal to the sum of measurements of both renal arteries and outflow. The main advantages of measuring blood flow in the aorta is the easier detection of the vessel, the easier planning of the flow measurement slice, and the limited motion during breathing limiting blurring of the vessel contour [22]. Conversely, the main drawback is the sometimes difficult placement of the inflow measurement slice, due to the close proximity of renal arteries to the mesenteric artery.

PC-MRI processing

Since blood flow measurement on PC-MRI is heavily affected by aliasing artifacts, a careful visual inspection beforehand is needed to have reliable RBF measurements. In case of artifacts, even if only in few voxels of a single time frame, the whole scan should be discarded [23].

Circular and elliptical regions of interest (ROIs) are commonly drawn on either the magnitude or the velocity images, covering the lumen but not the wall of the vessel of interest, with manual or semi-automatic methods using one of several processing software programs [9, 10, 16, 24,25,26,27,27]. ROIs cannot be kept constant across time frames, and should rather be adjusted in each of them, to account for movement of the vessels during the cardiac cycle, unless spatial registration was performed beforehand. Alternatively, automatic ROI segmentation techniques requiring no adjustment, such as adaptive thresholding [28], graph searching [29], active contour [30, 31], paraboloid velocity profiles [32] and k-mean clustering [8], show promise.

The mean blood velocity (expressed in cm/s) is usually computed as the average of the velocity images over all segmented pixels of all time frames [22, 33]. Then, the mean blood flow (Q, expressed in mL/min) (Fig. 1) is computed by multiplying the mean velocity \(({v}_{\mathrm{m}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{n}},\mathrm{ }\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n} \; \mathrm{ }\mathrm{c}\mathrm{m}/\mathrm{s})\) by the ROI area \((A)\) and the conversion factor between seconds and minutes:

In case of 3D PC-MRI, 3D reconstruction modules from a number of software programs can be used to visualize streamlines, assess 3D blood velocity vectors, and compute other hemodynamic parameters [20, 21]. However, at present, despite 3D PC-MRI being possible, it still needs further refinement in spatial and temporal resolution to robustly allow for quantification.

PC-MRI biomarkers

Discovery

The feasibility of PC-MRI to measure blood flow in renal vessels, using acquisition and processing methods described above, has been well demonstrated in a number of clinical studies (see Supplementary review table, Tables 2 and 3). In 1992, Sommer et al. first showed the promise of PC-MRI to reproducibly measure blood flow in renal arteries and veins [19]. Since then, a large body of studies have used PC-MRI to measure RBF, alongside a number of derivative biomarkers: renal plasma flow (RPF), computed as the product of RBF times (1-hematocrit); renal vascular resistance (RVR), computed as ratio between the mean arterial pressure (MAP) and RBF, or ratio between (mean peritubular capillary − renal venous pressure) and afferent RBF [15, 25, 34,35,36]; resistive index (RI), computed as [peak systolic (PSV) − minimum diastolic velocity (MDV)]/PSV [12, 34]; renal blood flow index (RBFI), computed as RBF normalized to body surface area [37]; filtration fraction (FF), computed as percentage of the ratio between creatinine clearance and RPF [17, 25, 38]; pulsatility index (PI), computed as (PSV − MDV)/MDV [12]. An additional biomarker which could be computed from PC-MRI is the systemic vascular resistance index (SVRI), defined as (MAP − central venous pressure)/cardiac index [38, 39].

Technical validation

Technical validation of quantitative PC-MRI has been performed by comparison with alternative velocimetry/flow measurement techniques both in vitro and in vivo (see Table 4).

Comparison of PC-MRI against fluid collection in phantoms of variable diameter Three studies have assessed PC-MRI flow measures in phantoms with a range of diameters to mimic the renal artery. King et al. [34] assessed RBF in a flow phantom of diameters of 2 and 5 mm with pulsatile flow. They showed PC-MRI accuracy was strongly related to phase-encoding pixel resolution, but when optimized, accuracy was excellent with errors in flow of < 1.4%. Dambreville et al. [40] performed prospective and retrospective gated PC-MRI in phantom studies, validating steady state and pulsatile PC-MRI flow measures against fluid collection. Results showed good accuracy, with deviations from true flow consistently below 13% for vessel diameters of 3 mm and above. Spithoven et al. [41] validated PC-MRI RBF measurements using flexible silicon phantoms of 5, 6, 7 and 8 mm renal artery diameter and 40% glycerol/60% purified water to mimic blood. RBF determined simultaneously with PC-MRI and fluid collection showed excellent agreement [correlation coefficient (r) of 0.97 (p < 0.001)].

Comparison of PC-MRI flow against ultrasound in vitro There are six studies using ultrasound measures as a reference technique for in vitro flow measurements, all of which show a high degree of correlation. Hoppe et al. [42] showed a good correlation (r = 0.95) between PC-MRI flow measurements in varying concentric stenosis with invasive Doppler guidewire measurements. PC-MRI velocity has been shown to be more accurate than Doppler ultrasound [43], suggested to arise from the fact that ultrasound only measures flow velocities along the axis of the ultrasonic beam. Laser Doppler velocimetry, which measures the velocity component of a single particle at a “given point” perpendicular to the axis of the light beam, has demonstrated a wide range of accuracy for PC-MRI for both steady state and pulsatile flows [44,45,46]. Particle image velocimetry, which concurrently acquires 2D velocity information, has been used to validate PC-MRI flow through stenotic phantoms with various degrees of narrowing (r > 0.99 and > 0.96 for steady and pulsatile flows) [47].

Comparison of in vivo PC-MRI flow measures with alternative methods In vivo measures of RBF measured using PC-MRI have been shown to yield a good correlation with “gold standard” methods of RBF measurement, including PAH clearance [41, 48,49,50,51,52,53], Doppler ultrasound flow probe measurements [53], 99mTc-DTPA scintigraphy [48] or 133Xenon washout flow measurements [54] (see “Biological validation”). Studies have developed and validated more advanced in vivo PC-MRI RBF measures. For example, Thomsen et al. [55] validated segmented k-space velocity mapping against conventional ECG-triggered PC-MRI, whilst Sommer et al. [50] compared spiral PC-MRI techniques, showing a range of agreement of ± 17.6% to ± 26.5%.

Reproducibility of in vivo PC-MRI flow measures Nine studies have shown good reproducibility and low intra- and inter-observer coefficient of variation (CV) of PC-MRI RBF measures, as summarized in Table 5. Keegan et al. [12] showed high reproducibility and low inter-observer variability of interleaved spiral phase velocity mapping for measurement of RBF and renal pulsatility indices. Abdominal 2D and 4D phase-contrast MR flow measurements have demonstrated strong repeatability and internal consistency of flow measurements [20]. Bax et al. [22] repeated PC-MRI measures in HVs as two successive scans or two scans collected at an interval of 7–21 days to differentiate between biological variation and measurement error. The mean total RBF of the HV kidney was 838 mL/min ± 244 (SD), whilst the CV was only slightly lower (17%) for two successive scans as opposed to the longer time interval (23%). A similar study assessed mean RBF and CV between two study days 1–2 weeks apart for HVs and chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients [15]. HVs and CKD patients had a single kidney RBF of 365 ± 119 mL/min and 170 ± 130 mL/min, with CVs of 8.3% and 12.9%, respectively. Dambreville et al. [40] demonstrated that breath-hold PC-MRI schemes show good week-to-week reproducibility, with a CV of 10.6%. Spithoven et al. [41] assessed PC-MRI flow measures performed three times in 21 ADPKD patients by two research physicians and showed an average intra-observer CV of 1.3% and inter-observer CV of 2.5% [34]. Both Cox et al. [13] and Kline et al. [36] measured the intra-subject repeatability of PC-MRI RBF as part of a multi-parametric renal MRI protocol, and reported a CV of 10.1% and 14.4%, respectively.

Biological validation

There are ten studies reporting comparisons of PC-MRI renal artery flow measurements against alternative techniques in humans. Of these, seven studies compared PC-MRI measurements against PAH clearance that, despite representing a suboptimal reference comparator [5], was used to estimate either ERPF or to calculate RBF from ERPF using the following equation: RBF = ERPF/(1 − hematocrit) [1, 19, 38, 48,49,50,51] (Table 4). A further three studies compared PC-MRI of renal artery flow with the difference in aortic flow (also measured by PC-MRI) above and below the renal arteries [14, 22, 52]. However, as this approach is making comparisons against the same measurement technique, it is best considered an assessment of internal validity. Finally, two of the included studies incorporated experimental arms in which PC-MRI was compared with direct measures of vessel flow. Schoenberg et al. obtained in vivo reference measurements using a transit-time US flow probe surgically implanted in the left renal artery of seven dogs [24] and using the same US method, Debatin compared measures of flow in an ex vivo phantom constructed using a 6-cm segment of human renal artery [49].

Comparisons against PAH clearance All studies were small in size (range 8–14 participants); five were undertaken in HVs [19, 38, 49,50,51], one in people with CKD [48] and one in renal transplant recipients [1]. Direct comparisons between studies are difficult as a variety of methods for PC acquisition were used, and in two studies more than one method were reported [14, 49, 50]. In addition, there was heterogeneity across studies in whether ERPF or RBF values were used as the comparator and in statistical analysis approaches. Three of the studies in HVs reported good agreement between PC-MRI renal artery flow and PAH methods. Debatin reported that the best of three different PC-MRI techniques studied had a low mean difference of 2.8 ± 7.1% versus PAH RPF [49]. In a similar study that also assessed different PC-MRI methods, Sommer et al. found mean differences that ranged from 0 mL/min (95% CI − 166 to 166 mL/min) at best to 95 mL/min (95% CI − 154 to 341 mL/min) [50]. Wolf et al. also reported good agreement [39 mL/min mean difference (95% CI − 100 to 177 mL/min)], although results differed slightly depending on velocity encoding [51]. A single study in nine participants reported better correlations between PC-MRI measures of renal vein flow and PAH as compared to arterial flow [50]; this informed a follow-on study in 14 renal transplant recipients with preserved renal function that found both good correlation (r = 0.92) and low mean difference (20 mL/min, 95% CI − 214 to 254 mL/min) between the two techniques [1]. The only study that included participants with reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) showed a reasonable correlation between PAH and PC-MRI measures of RBF, noting that only eight patients were studied and PAH may be less accurate if tubular secretion is impaired [48]. Finally, Van der Bel et al. reported changes in PC-MRI renal artery blood flow and ERPF in response to angiotensin infusion in 8 HVs and showed similar patterns of change but did not directly compare the two measurement techniques [38].

Comparison against aortic inflow/outflow Three studies compared direct measures of renal artery flow by PC-MRI against difference in PC-MRI measures of aortic flow above and below the renal arteries [14, 22, 52]. In 18 HVs, Bax et al. reported a reasonable correlation between the two (r = 0.72, p = 0.002) [22]. De Haan showed a similar correlation in a graphical figure without reporting values [14], whilst Lundin reported no significant difference in mean total RBF calculated from the sum of the renal artery flows (RAs) versus flow calculated from the aortic difference (mean ratio RBF: aortic difference 1.06 ± 0.04, range 0.79–1.20) [52].

Experimental studies Whilst this review was restricted to studies in humans, two studies included experimental arms. Schoenberg reported that the relative accuracy of mean flow measured by PC-MRI was within 4.1 ± 2.9% of that measured by transit time ultrasound in the left renal artery of seven dogs [24]. In an ex vivo phantom built with a human renal artery, Debatin found a range of mean differences (42.1 ± 10%, − 10.4 ± 17.3% and − 2.4 ± 2.5%) across three PC-MRI methodologies [49]. Notably, the method that performed best in this study was shown to have the greatest bias in the study of Sommer comparing against PAH clearance in vivo [50].

PC-MRI clinical application in renal disease

Chronic kidney disease

In patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), structural changes, including reduction in total nephron number, interstitial fibrosis, and/or vascular rarefication [56] often develop before measurable functional changes [57]. Structural changes may be associated with multiple systemic diseases, for instance diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and arteriosclerosis, and may in turn affect RBF, likely reducing it due to the increased resistance of renal microcirculation. Moreover, while in healthy subjects the kidney is very effective in regulating blood flow over a wide range of blood pressures and in maintaining glomerular pressure and filtration rate, in patients with CKD this autoregulation may be gradually lost, as renal function declines, resulting in RBF decrease. In addition, CKD patients receive a wide range of drugs, including diuretics and renin–angiotensin system inhibitors, which may alter renal function and blood flow and influence renal hemodynamics. There are only few studies using PC-MRI in CKD (Table 3), and the method is currently not used routinely to assess RBF in patients with CKD in the clinic. A good reproducibility of respiratory-gated PC-MRI was identified in CKD patients and HVs, when examined 1–2 weeks apart, revealing coefficients of variation of 12.9% and 8.3%, respectively [15]. RBF measured by PC-MRI was significantly decreased in CKD patients compared to HVs [15, 48, 58], even in patients with mild-to-moderate CKD, although the HVs were 8 years younger [13]. Combining PC-MRI and arterial spin labeling (ASL), Michaely et al. were able to separate healthy kidneys from kidneys with vascular, parenchymal or combined disease [59]. In patients with CKD, measured GFR was reduced to a greater extent than RBF, resulting in a reduced filtration fraction, which may reflect an adaptation to keep intra-renal oxygenation within normal range [58]. Last, PC-MRI was used to measure renal arterial blood flow and calculate renal vascular resistance in a study comparing vasodilatory and non-vasodilatory antihypertensive treatment in patients with CKD. After 18-month follow-up, RABF increased significantly in both groups, but the change did not differ between groups [60].

Acute kidney injury

Changes in RBF and/or perfusion are considered critical to the etiology of many forms of acute kidney injury (AKI). However, PC-MRI has only rarely been applied in people with AKI, which may in part reflect the perceived logistical difficulties of scanning acutely unwell patients. Following an initial report of feasibility [39], Prowle et al. have shown that it is possible to successfully perform PC-MRI in intensive care unit (ICU) patients with sepsis-associated AKI. In a pilot study of 10 people, of whom 8 were mechanically ventilated, 9 were on continuous hemofiltration and 5 required vasopressors, RBF and cardiac output (CO) were measured and compared with 11 HVs [37]. Results, which should be regarded as exploratory, showed that median RBF in septic AKI (482 mL/min) was lower than that in healthy controls (1260 mL/min); that there was considerable variation in RBF measures (range 335–1137 mL/min in AKI group); and that RBF as a proportion of CO was also reduced (suggesting a dependency of RBF on changes in CO).

Renovascular disease/renal artery stenosis

Renal artery stenosis (RAS) is a leading cause of secondary hypertension and can cause CKD. In unselected populations, several large trials have failed to show significant benefit to intervention with angioplasty and/or stenting [61, 62]. Despite these findings, debate continues as to whether subgroups of patients with RAS may benefit from intervention, and if so how best to identify them. A small number of studies have, therefore, applied PC-MRI to patients with RAS to determine whether functional measurements of renal artery flow/velocity provide additional clinical information. Seven studies report on the use of PC-MRI in the context of renovascular disease [16, 17, 27, 59, 63,64,65].

Several studies evaluated whether PC-MRI can improve characterization or detection of anatomical severity of renal artery lesions (Table 3). In RAS, Cine PC-MRI demonstrates a damped systolic wave which is longer in duration [66]. Schoenberg et al. performed cardiac-gated Cine PC-MRI in 23 patients with 48 areas of RAS and MR flow measures were compared against severity of anatomical stenosis [24]. To separate those with > 50% stenosis from those with no stenosis, PC-MRI was reported to have 100% sensitivity and 93% specificity. In 11 patients, ultrasound flow measures of the renal artery were also taken at time of surgical intervention and correlated well with PC-MRI measures. Post-operative PC-MRI flow values improved, but no clinical outcomes were reported. It has also been hypothesized that intravenous angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) administration may improve diagnostic accuracy of waveform analysis, but this was not borne out in a study of 35 patients [16]. In a pilot study, Bock et al. compared two PC-MRI techniques (interleaved gradient echo-planar technique (IGEPI) Cine PC-MRI and conventional Cine PC-MRI [67]. IGEPI Cine PC-MRI detected 5/5 high-grade stenosis versus 3/5 (66%) with conventional Cine PC-MRI. Later, Schoenberg et al. demonstrated that a combined morphologic and functional MR examination significantly reduced inter-observer variability across 7 readers evaluating 43 renal arteries [65, 68]. They reported that this approach offered reliable, reproducible grading of RAS when compared with X-ray digital subtraction angiography (DSA) AND 3D gadolinium MR.

Binkert et al. combined arterial flow volume and renal volume in 130 kidneys from 65 patients in attempt to determine functional significance of RAS lesions [64]. Of 31 kidneys with RAS, 18 had significantly reduced volume [3.08 ± 0.75 (au)] and significantly reduced flow volumes (91.56 vs 279.15 mL/min without RAS). Based on the Renal Flow Index (RFI) (flow/renal volumes), there was only minimal overlap between normal volume kidneys with RAS and those without RAS suggesting that RFI could be used to predict the likelihood of hemodynamically significant RAS. The same group later went on to investigate whether this information could be used to predict positive clinical outcomes following percutaneous angioplasty [63]. In a group of 23 patients, 34 areas of RAS were present and 11 people had bilateral disease. Clinical success (defined as a fall in diastolic BP by > 15% or a fall in creatinine of > 20%) was observed in 11 patients, 10 of whom had normal kidney volume pre-intervention. The sensitivity of RFI to predict response to therapy was reasonable (91%) but specificity low, suggesting that direct translation of this method to clinical practice would result in a significant rate of unnecessary procedures. RFI < 1.5 mL/min/cm3 had a 100% sensitivity predicting clinical benefit, but low specificity of 33%, although combining with clinical variables improved specificity somewhat to 67%.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

PC-MRI has been used to non-invasively measure RBF in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) (Table 3) since 2003 when, in a large study of 127 patients with early ADPKD, RBF was shown to have high accuracy and intra- and inter-observer reproducibility, to strongly correlate with both renal volumes and GFR, and to predict GFR [34]. In a subsequent longitudinal study by the same group including 131 patients with early ADPKD, RBF decreased over 3-year follow-up, preceding GFR decline, was negatively correlated with total kidney (TKV) and total cyst volume slopes, and positively correlated with GFR slope, predicting structural and functional disease progression and showing promise as outcome measure in clinical trials on ADPKD [25]. PC-MRI was used in a small clinical trial to investigate, alongside GFR and TKV, the short-term effects of Tolvaptan in patients with ADPKD; the study found no significant change in RBF after 1 week of Tolvaptan treatment, with PC-MRI mirroring PAH clearance flow measurements [69]. More recently, Spithoven and colleagues provided additional evidence of accuracy and validity of RBF measurement by PC-MRI as compared with RBF measured by continuous hippuran infusion, in a cohort of 91 ADPKD patients with a wide range of eGFR values. In this study, RBF values were associated with ADPKD severity, and technical problems preventing RBF measurement occurred predominantly in patients with lower eGFR (< 70 mL/min), suggesting that RBF measurement may be less feasible in patients with ADPKD at an advanced stage [41]. Last, PC-MRI was performed in a small cohort of young patients with early-stage ADPKD and normal controls, as part of a comprehensive multi-parametric renal MRI protocol. Besides its preliminary results, showing no statistically significant difference in RBF between young ADPKD patients and normal controls [36], the study represents a valuable attempt to combine PC-MRI with other quantitative renal MR techniques towards a comprehensive characterization of the ADPKD kidney tissue and function.

Discussion

The current published literature supports PC-MRI as a feasible and valid non-invasive technique to reliably measure renal blood flow, alongside a number of derivative hemodynamic parameters, in both HVs and patients with renal disease. There are a few key recommendations (summarized in Table 1) to be followed to accurately measure RBF by PC-MRI, possibly reducing the wide variability in the measurements reported so far (Table 2). As a potential confounder, patient hydration should be controlled whenever possible. The acquisition slice should be placed perpendicularly to the vessel direction, and prior to any bifurcation; to this purpose, a good survey scan (e.g. angiography) is extremely helpful. To minimize acquisition time and flow-induced artifacts without compromising signal-to-noise ratio, relaxation and echo times should be minimum, velocity encoding should be higher than the peak velocity (around 100 cm/s), flip angle should be low [in [10°–30°] range); spatial resolution should be sufficient to enable reliable identification of the vessels. Motion compensation should be performed by breath-hold or respiratory gating, and either prospective or retrospective cardiac gating should be used, especially for arterial flow measurements. Once acquired, PC-MRI should undergo a careful visual inspection, and images with any artifact should be discarded. To quantify renal blood velocity and volume, circular or elliptic ROIs should be defined, covering the lumen but not the vessel wall. Importantly, these ROIs should be adjusted to account for movement of the vessels during the cardiac cycle, many software packages perform such automatic tracking but this should be visually checked. PC-MRI acquisition and post-processing procedures are quite straightforward with standard software, so there is no need for a high-level of technical expertise.

PC-MRI has been technically validated in a number of studies both in vitro, using flow phantoms, and in vivo, generally showing good correlation with gold-standard methods of RBF measurement. Moreover, a large number of studies have investigated the reproducibility, and intra- and inter-observer CV of RBF measures obtained by PC-MRI, showing an overall good reproducibility. PC-MRI has been biologically validated against alternative techniques in humans, especially against PAH clearance, showing an overall good agreement between PC-MRI and PAH measurements. In addition, PC-MRI has been experimentally validated against direct measures of vessel flow [24, 49], although this is out of the scope of this clinical review. Despite PC-MRI not being routinely used in clinics, there are a number of clinical studies showing its potential to support diagnosis and monitoring of renal diseases, in particular CKD, renovascular disease, and ADPKD, particularly in the earlier stages. In HVs, the variability in RBF values, both in individual studies and across studies, is rather large, making the definition of normative ranges not possible yet. Future large multicentric studies are needed to provide reliable and definitive reference ranges.

PC-MRI is likely to benefit from combination with other promising renal MRI techniques (such as BOLD [70], DWI [71], T1 and T2 mapping [72], and ASL [73]) providing complementary information on renal microstructure and function and enabling a complete assessment of the normal and diseased kidney, potentially improving renal disease diagnosis and monitoring. Multi-parametric renal MRI has been recently pioneered in patients with CKD [13] and ADPKD [36]. Future multicenter studies are needed to demonstrate the clinical potential of PC-MRI as part of a multi-parametric renal MRI protocol. International collaborative efforts such as the COST action PARENCHIMA (https://www.renalmri.org) may help in answering this need.

Change history

11 June 2020

The article Phase���contrast magnetic resonance imaging to assess renal perfusion: a systematic review and statement paper, written by Giulia Villa, Steffen Ringgaard, Ingo Hermann, Rebecca Noble, Paolo Brambilla, Dinah S. Khatir, Frank G. Z��llner, Susan T. Francis, Nicholas M. Selby, Andrea Remuzzi and Anna Caroli, was originally published electronically on the publisher���s internet portal on 17 August 2019 without open access

References

Myers BD, Sommer FG, Li K, Tomlanovich S, Pelc N, McDonnell C, Pagtalunan E, Newton L, Jamison R (1994) Determination of blood flow to the transplanted kidney. A novel application of phase-contrast, cine magnetic resonance imaging. Transplantation 57:1445–1450

Morelli E, Loon N, Meyer T, Peters W, Myers BD (1990) Effects of converting-enzyme inhibition on barrier function in diabetic glomerulopathy. Diabetes 39:76–82

Molina CR, Fowler MB, Mccrory S, Peterson C, Myers BD, Schroeder JS, Murad F (1988) Hemodynamic, renal and endocrine effects of atrial natriuretic peptide infusion in severe heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 12:175

Battilana C, Zhang HP, Olshen RA, Wexler L, Myers BD (1991) PAH extraction and estimation of plasma flow in diseased human kidneys. Am J Physiol 261:F726–F733

Smith HW (1952) The kidney: structure and function in health and disease. Oxford University Press, New York

Nayak KS, Nielsen J-F, Bernstein MA, Markl M, Gatehouse PD, Botnar M, R, Saloner D, Lorenz C, Wen H, Hu BS, Epstein FH, Oshinski JN, Raman SV, (2015) Cardiovascular magnetic resonance phase contrast imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 17:71

Groves AM (2011) Cardiac magnetic resonance in the study of neonatal haemodynamics. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 16:36–41

Zöllner FG, Ankar Monssen J, Rørvik J, Lundervold A, Schad LR (2009) Blood flow quantification from 2D phase contrast MRI in renal arteries using an unsupervised data driven approach. Zeitschrift für Medizinische Physik 19:98–107

Park JB, Santos JM, Hargreaves BA, Nayak KS, Sommer G, Hu BS, Nishimura DG (2005) Rapid measurement of renal artery blood flow with ungated spiral phase-contrast MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 21:590–595

Steeden JA, Muthurangu V (2015) Investigating the limitations of single breath-hold renal artery blood flow measurements using spiral phase contrast MR with R–R interval averaging: spiral PCMR with R–R interval averaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 41:1143–1149

Nickander J, Lundin M, Jenner J, Maret E, Sörensson P, Sigfridsson A, Ugander M (2015) Background phase correction in phase contrast velocity encoded CMR reduces gender differences and improves the accuracy and precision of Qp/Qs. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-17-S1-P65

Keegan J, Patel HC, Simpson RM, Mohiaddin RH, Firmin DN (2015) Inter-study reproducibility of interleaved spiral phase velocity mapping of renal artery haemodynamics. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-014-0105-x

Cox EF, Buchanan CE, Bradley CR, Prestwich B, Mahmoud H, Taal M, Selby NM, Francis ST (2017) Multiparametric renal magnetic resonance imaging: validation, interventions, and alterations in chronic kidney disease. Front Physiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00696

de Haan MW, Kouwenhoven M, Kessels AGH, van Engelshoven JMA (2000) Renal artery blood flow: quantification with breath-hold or respiratory triggered phase-contrast MR imaging. Eur Radiol 10:1133–1137

Khatir DS, Pedersen M, Jespersen B, Buus NH (2014) Reproducibility of MRI renal artery blood flow and BOLD measurements in patients with chronic kidney disease and healthy controls: reproducibility of RABF and BOLD in CKD. J Magn Reson Imaging 40:1091–1098

Lee VS, Rofsky NM, Ton AT, Johnson G, Krinsky GA, Weinreb JC (2000) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-enhanced phase-contrast MR imaging to measure renal artery velocity waveforms in patients with suspected renovascular hypertension. Am J Roentgenol 174:499–508

Maier SE, Scheidegger MB, Liu K, Schneider E, Bellinger A, Boesiger P (1995) Renal artery velocity mapping with MR imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 5:669–676

Hofman MB, Visser FC, van Rossum AC, Vink QM, Sprenger M, Westerhof N (1995) In vivo validation of magnetic resonance blood volume flow measurements with limited spatial resolution in small vessels. Magn Reson Med 33:778–784

Sommer G, Noorbehesht B, Pelc N, Jamison R, Pinevich AJ, Newton L, Myers B (1992) Normal renal blood flow measurement using phase-contrast cine magnetic resonance imaging. Investig Radiol 27:465–470

Wentland AL, Grist TM, Wieben O (2013) Repeatability and internal consistency of abdominal 2D and 4D phase contrast MR flow measurements. Acad Radiol 20:699–704

Scheuer S, Zöllner FG, Tumat E, Schad LR (2010) Untersuchung von Strömungsverhältnissen an künstlichen Modellen mittelgroßer stenotischer Gefäße mit der 3D-Phasenkontrast-Magnetresonanztomographie. Zeitschrift für Medizinische Physik 20:34–45

Bax L, Bakker CJG, Klein WM, Blanken N, Beutler JJ, Mali WPTRM (2005) Renal blood flow measurements with use of phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging: normal values and reproducibility. J Vasc Interv Radiol 16:807–814

Lotz J, Meier C, Leppert A, Galanski M (2002) Cardiovascular flow measurement with phase-contrast MR imaging: basic facts and implementation. RadioGraphics 22:651–671

Schoenberg SO, Knopp MV, Bock M, Kallinowski F, Just A, Essig M, Hawighorst H, Schad L, van Kaick G (1997) Renal artery stenosis: grading of hemodynamic changes with cine phase-contrast MR blood flow measurements. Radiology 203:45–53

Torres VE, King BF, Chapman AB, Brummer ME, Bae KT, Glockner JF, Arya K, Risk D, Felmlee JP, Grantham JJ, Guay-Woodford LM, Bennett WM, Klahr S, Meyers CM, Zhang X, Thompson PA, Miller JP, The Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease (CRISP) (2006) Magnetic resonance measurements of renal blood flow and disease progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2:112–120

Wittsack H-J, Lanzman RS, Quentin M, Kuhlemann J, Klasen J, Pentang G, Riegger C, Antoch G, Blondin D (2012) Temporally resolved electrocardiogram-triggered diffusion-weighted imaging of the human kidney: correlation between intravoxel incoherent motion parameters and renal blood flow at different time points of the cardiac cycle. Investig Radiol 47:226–230

Ishikawa T, Takehara Y, Yamashita S, Iwashima S, Sugiyama M, Wakayama T, Johnson K, Wieben O, Sakahara H, Ogata T (2015) Hemodynamic assessment in a child with renovascular hypertension using time-resolved three-dimensional cine phase-contrast MRI: RVH assessed with 3D Cine PC MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 41:165–168

Alperin N, Lee SH (2003) PUBS: pulsatility-based segmentation of lumens conducting non-steady flow. Magn Reson Med 49:934–944

Lalande A, Khau van Kien P, Salve N, Ben Salem D, Legrand L, Walker PM, Wolf J-E, Brunotte F (2002) Automatic determination of aortic compliance with cine-magnetic resonance imaging: an application of fuzzy logic theory. Investig Radiol 37:685–691

Kozerke S, Botnar R, Oyre S, Scheidegger MB, Pedersen EM, Boesiger P (1999) Automatic vessel segmentation using active contours in cine phase contrast flow measurements. J Magn Reson Imaging 10:41–51

Herment A, Kachenoura N, Lefort M, Bensalah M, Dogui A, Frouin F, Mousseaux E, De Cesare A (2010) Automated segmentation of the aorta from phase contrast MR images: validation against expert tracing in healthy volunteers and in patients with a dilated aorta. J Magn Reson Imaging 31:881–888

Oyre S, Ringgaard S, Kozerke S, Paaske WP, Scheidegger MB, Boesiger P, Pedersen EM (1998) Quantitation of circumferential subpixel vessel wall position and wall shear stress by multiple sectored three-dimensional paraboloid modeling of velocity encoded cine MR. Magn Reson Med 40:645–655

Hackstein N, Schneider C, Eichner G, Rau WS (2007) Effect of IV injection of radiographic contrast media on human renal blood flow. Am J Roentgenol 188:1367–1372

King BF, Torres VE, Brummer ME, Chapman AB, Bae KT, Glockner JF, Arya K, Felmlee JP, Grantham JJ, Guay-Woodford LM, Bennett WM, Klahr S, Hirschman GH, Kimmel PL, Thompson PA, Miller JP; Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease (CRISP) (2003) Magnetic resonance measurements of renal blood flow as a marker of disease severity in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 64:2214–2221

van der Bel R, Verbree J, Gurney-Champion OJ, van Osch MJP, Stroes ESG, Nederveen AJ, Krediet CTP (2018) Sympathetic activation by lower body negative pressure decreases kidney perfusion without inducing hypoxia in healthy humans. Clin Auton Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10286-018-0570-7

Kline TL, Edwards ME, Garg I, Irazabal MV, Korfiatis P, Harris PC, King BF, Torres VE, Venkatesh SK, Erickson BJ (2018) Quantitative MRI of kidneys in renal disease. Abdom Radiol 43:629–638

Prowle JR, Molan MP, Hornsey E, Bellomo R (2012) Measurement of renal blood flow by phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging during septic acute kidney injury: a pilot investigation*. Crit Care Med 40:1768–1776

van der Bel R, Coolen BF, Nederveen AJ, Potters WV, Verberne HJ, Vogt L, Stroes ESG, Krediet CTP (2016) Magnetic resonance imaging-derived renal oxygenation and perfusion during continuous, steady-state angiotensin-II infusion in healthy humans. J Am Heart Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.115.003185

Prowle JR, Molan MP, Hornsey E, Bellomo R (2010) Ciné phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging for the measurement of renal blood flow. In: Ronco C, Bellomo R, McCullough PA (eds) Contributions to nephrology. Karger, Basel, pp 329–336

Dambreville S, Chapman AB, Torres VE, King BF, Wallin AK, Frakes DH, Yoganathan AP, Wijayawardana SR, Easley K, Bae KT, Brummer ME, Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease (CRISP) (2010) Renal arterial blood flow measurement by breath-held MRI: accuracy in phantom scans and reproducibility in healthy subjects. Magn Reson Med 63:940–950

Spithoven EM, Meijer E, Borns C, Boertien WE, Gaillard CAJM, Kappert P, Greuter MJW, van der Jagt E, Vart P, de Jong PE, Gansevoort RT (2016) Feasibility of measuring renal blood flow by phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Eur Radiol 26:683–692

Hoppe M, Heverhagen JT, Froelich JJ, Kunisch-Hoppe M, Klose KJ, Wagner HJ (1998) Correlation of flow velocity measurements by magnetic resonance phase contrast imaging and intravascular Doppler ultrasound. Investig Radiol 33:427–432

Lee VS, Spritzer CE, Carroll BA, Pool LG, Bernstein MA, Heinle SK, MacFall JR (1997) Flow quantification using fast cine phase-contrast MR imaging, conventional cine phase-contrast MR imaging, and Doppler sonography: in vitro and in vivo validation. Am J Roentgenol 169:1125–1131

Siegel JMJ, Oshinski JN, Pettigrew RI, Ku DN (1996) The accuracy of magnetic resonance phase velocity measurements in stenotic flow. J Biomech 29:1665–1672

Hollnagel DI, Summers PE, Poulikakos D, Kollias SS (2009) Comparative velocity investigations in cerebral arteries and aneurysms: 3D phase-contrast MR angiography, laser Doppler velocimetry and computational fluid dynamics. NMR Biomed 22:795–808

Ku DN, Biancheri CL, Pettigrew RI, Peifer JW, Markou CP, Engels H (1990) Evaluation of magnetic resonance velocimetry for steady flow. J Biomech Eng 112:464–472

Khodarahmi I, Shakeri M, Kotys-Traughber M, Fischer S, Sharp MK, Amini AA (2014) In vitro validation of flow measurement with phase contrast MRI at 3 tesla using stereoscopic particle image velocimetry and stereoscopic particle image velocimetry-based computational fluid dynamics. J Magn Reson Imaging 39:1477–1485

Cortsen M, Petersen LJ, Ståhlberg F, Thomsen C, Søndergaard L, Petersen JR, Ladefoged SD, Henriksen O (1996) MR velocity mapping measurement of renal artery blood flow in patients with impaired kidney function. Acta Radiol 37:79–84

Debatin JF, Ting RH, Wegmüller H, Sommer FG, Fredrickson JO, Brosnan TJ, Bowman BS, Myers BD, Herfkens RJ, Pelc NJ (1994) Renal artery blood flow: quantitation with phase-contrast MR imaging with and without breath holding. Radiology 190:371–378

Sommer G, Corrigan G, Fredrickson J, Sawyer-Glover A, Liao JR, Myers B, Pelc N (1998) Renal blood flow: measurement in vivo with rapid spiral MR imaging. Radiology 208:729–734

Wolf RL, King BF, Torres VE, Wilson DM, Ehman RL (1993) Measurement of normal renal artery blood flow: cine phase-contrast MR imaging vs clearance of p-aminohippurate. Am J Roentgenol 161:995–1002

Lundin B, Cooper TG, Meyer RA, Potchen EJ (1993) Measurement of total and unilateral renal blood flow by oblique-angle velocity-encoded 2D-CINE magnetic resonance angiography. Magn Reson Imaging 11:51–59

Pelc LR, Pelc NJ, Rayhill SC, Castro LJ, Glover GH, Herfkens RJ, Miller DC, Jeffrey RB (1992) Arterial and venous blood flow: noninvasive quantitation with MR imaging. Radiology 185:809–812

de Haan MW, van Engelshoven JMA, Houben AJHM, Kaandorp DW, Kessels AGH, Kroon AA, de Leeuw PW (2003) Phase-contrast magnetic resonance flow quantification in renal arteries: comparison with 133Xenon washout measurements. Hypertension 41:114–118

Thomsen C, Cortsen M, Söndergaard L, Henriksen O, Ståhlberg F (1995) A segmented k-space velocity mapping protocol for quantification of renal artery blood plow during breath-holding. J Magn Reson Imaging 5:393–401

Levey AS, Coresh J (2012) Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 379:165–180

Wang X, Vrtiska TJ, Avula RT, Walters LR, Chakkera HA, Kremers WK, Lerman LO, Rule AD (2014) Age, kidney function, and risk factors associate differently with cortical and medullary volumes of the kidney. Kidney Int 85:677–685

Khatir DS, Pedersen M, Jespersen B, Buus NH (2015) Evaluation of renal blood flow and oxygenation in CKD using magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Kidney Dis 66:402–411

Michaely HJ, Schoenberg SO, Ittrich C, Dikow R, Bock M, Guenther M (2004) Renal disease: value of functional magnetic resonance imaging with flow and perfusion measurements. Investig Radiol 39:698–705

Khatir DS, Pedersen M, Ivarsen P, Christensen KL, Jespersen B, Buus NH (2019) Effects of additional vasodilatory or nonvasodilatory treatment on renal function, vascular resistance and oxygenation in chronic kidney disease: a randomized clinical trial. J Hypertens 37:116–124

Wheatley K, Ives N, Gray R, Kalra PA, Moss JG, Baigent C, Carr S, Chalmers N, Eadington D, Hamilton G, Lipkin G, Nicholson A, Scoble J (2009) Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 361:1953–1962

Cooper CJ, Murphy TP, Cutlip DE, Jamerson K, Henrich W, Reid DM, Cohen DJ, Matsumoto AH, Steffes M, Jaff MR, Prince MR, Lewis EF, Tuttle KR, Shapiro JI, Rundback JH, Massaro JM, D’Agostino RBS, Dworkin LD (2014) Stenting and medical therapy for atherosclerotic renal-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med 370:13–22

Binkert CA, Debatin JF, Schneider E, Hodler J, Ruehm SG, Schmidt M, Hoffmann U (2001) Can MR measurement of renal artery flow and renal volume predict the outcome of percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty? Cardiovasc Interv Radiol 24:233–239

Binkert CA, Hoffman U, Leung DA, Matter H-G, Schmidt M, Debatin JF (1999) Characterization of renal artery stenoses based on magnetic resonance renal flow and volume measurements. Kidney Int 56:1846–1854

Schoenberg SO, Knopp MV, Londy F, Krishnan S, Zuna I, Lang N, Essig M, Hawighorst H, Maki JH, Stafford-Johnson D, Kallinowski F, Chenevert TL, Prince MR (2002) Morphologic and functional magnetic resonance imaging of renal artery stenosis: a multireader tricenter study. J Am Soc Nephrol 13:158–169

Westenberg JJM, Wasser MNJM, van der Geest RJ, Pattynama PMT, de Roos A, Vanderschoot J, Reiber JHC (1998) Variations in blood flow waveforms in stenotic renal arteries by 2D phase-contrast cine MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 8:590–597

Bock M, Schoenberg SO, Schad LR, Knopp MV, Essig M, van Kaick G (1998) Interleaved gradient echo planar (IGEPI) and phase contrast CINE-PC flow measurements in the renal artery. J Magn Reson Imaging 8:889–895

Schoenberg SO, Rieger JR, Michaely HJ, Rupprecht H, Samtleben W, Reiser MF (2006) Functional magnetic resonance imaging in renal artery stenosis. Abdom Imaging 31:200–212

Irazabal MV, Torres VE, Hogan MC, Glockner J, King BF, Ofstie TG, Krasa HB, Ouyang J, Czerwiec FS (2011) Short-term effects of tolvaptan on renal function and volume in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 80:295–301

Pruijm M, Mendichovszky IA, Liss P, Van der Niepen P, Textor SC, Lerman LO, Krediet CTP, Caroli A, Burnier M, Prasad PV (2018) Renal blood oxygenation level-dependent magnetic resonance imaging to measure renal tissue oxygenation: a statement paper and systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transpl 33:ii22–ii28

Caroli A, Schneider M, Friedli I, Ljimani A, De Seigneux S, Boor P, Gullapudi L, Kazmi I, Mendichovszky IA, Notohamiprodjo M, Selby NM, Thoeny HC, Grenier N, Vallée J-P (2018) Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging to assess diffuse renal pathology: a systematic review and statement paper. Nephrol Dial Transpl 33:ii29–ii40

Wolf M, de Boer A, Sharma K, Boor P, Leiner T, Sunder-Plassmann G, Moser E, Caroli A, Jerome NP (2018) Magnetic resonance imaging T1- and T2-mapping to assess renal structure and function: a systematic review and statement paper. Nephrol Dial Transpl 33:ii41–ii50

Odudu A, Nery F, Harteveld AA, Evans RG, Pendse D, Buchanan CE, Francis ST, Fernández-Seara MA (2018) Arterial spin labelling MRI to measure renal perfusion: a systematic review and statement paper. Nephrol Dial Transpl 33:ii15–ii21

Jin N, Lewandowski RJ, Omary RA, Larson AC (2009) Respiratory self-gating for free-breathing abdominal phase-contrast blood flow measurements. J Magn Reson Imaging 29:860–868

Eckerbom P, Hansell P, Cox E, Buchanan C, Weis J, Palm F, Francis S, Liss P (2019) Multiparametric assessment of renal physiology in healthy volunteers using noninvasive magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol 316:F693–F702

Acknowledgements

This article is based upon work from COST Action Magnetic Resonance Imaging Biomarkers for Chronic Kidney Disease (PARENCHIMA), funded by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology). https://www.cost.eu. For additional information please visit PARENCHIMA homepage: https://www.renalmri.org.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GV: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of manuscript. SR: analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision. IH: analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision. RN: analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision. PB: analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision. DK: analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision. FGZ: analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision. SF: analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision. NMS: analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision. AR: study conception and design, and critical revision. AC: study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Villa, G., Ringgaard, S., Hermann, I. et al. Phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging to assess renal perfusion: a systematic review and statement paper. Magn Reson Mater Phy 33, 3–21 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-019-00772-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-019-00772-0