Abstract

While much can be learned about primates by means of observation, the slow life history of many primates means that even decades of dedicated effort cannot illuminate long-term evolutionary processes. For example, while the size of a contemporary population can be estimated from field censuses, it is often desirable to know whether a population has been constant or changing in size over a time frame of hundreds or thousands of years. Even the nature of “a population” is open to question, and the extent to which individuals successfully disperse among defined populations is also difficult to estimate by using observational methods alone. Researchers have thus turned to genetic methods to examine the size, structure, and evolutionary histories of primate populations. Many results have been gained by study of sequence variation of maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA, but in recent years researchers have been increasingly focusing on analysis of short, highly variable microsatellite segments in the autosomal genome for a high-resolution view of evolutionary processes involving both sexes. In this review we describe some of the insights thus gained, and discuss the likely impact on this field of new technologies such as high-throughput DNA sequencing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Primates are a favorite subject of studies in molecular ecology, a field which employs molecular genetic techniques to address questions linking ecology, behavior, social structure, and conservation in an evolutionary context. However, in contrast with other well-studied species groups, for example birds (Griffith et al. 2002; Westneat and Stewart 2003), reptiles (Uller and Olsson 2008), and fish (Garcia de Leaniz et al. 2007; Crispo and Chapman 2008; Rocha and Bowen 2008), studies of primates face particular challenges. First, as compared with most primates, many small vertebrates are numerous, occur at high density, and have a fast life-history and short generation time. This means it can take much more time and effort to accumulate data from a large-bodied primate population. Second, many small-bodied, and even large-bodied, vertebrates can be captured and directly handled, providing researchers with accurate measurements of morphological characteristics and high-quality samples of tissue or blood, for example Soay sheep (Coltman et al. 1999), deer on the Isle of Rum (Nussey et al. 2006), and meerkats (Griffin et al. 2003). With some exceptions, for example lemur (Wimmer and Kappeler 2002; Olivieri et al. 2007) and baboon (Jolly et al. 1997), noninvasive sampling methods and minimally disruptive observation are preferred for study of primates. Third, experimental manipulation of aspects such as resource availability, population density, and mating partners are increasingly eschewed for primates because of potentially negative impacts upon their social organization and stability. Finally, many primate species are difficult to observe because of their cryptic behavior. Therefore, to reduce the impact of human research activities on primates, molecular primatologists often rely on noninvasive samples bearing limited amounts of DNA; this makes genetic analysis more difficult.

Despite the challenges, molecular studies have been successfully undertaken on many primate species, as will be described in this review. Among the pioneers were Japanese researchers who conducted genetic structure analyses on endemic macaque species in the early 1980s using blood protein polymorphism (Nozawa et al. 1982). A landmark publication in 1992, a volume entitled Paternity in Primates, marked the advent of an intense focus on ascertaining genetic relationships, particularly paternity, among members of social groups (Martin et al. 1992). The aim of studies quickly broadened to understanding dispersal patterns, mating systems, reproductive strategies, and the influence of kinship on social behavior (Di Fiore 2003). Such studies have mainly been conducted at the level of the social group. However, processes operating at the level of the social group will affect the patterning of genetic variation across the population and species in question. In this review we will attempt to provide an overview of how behavior, social structure, and population genetic structure can be linked by genetic studies of primate populations aimed at providing insights into the size, structure, and evolutionary histories of primate populations.

What is a population?

The term population can and has been used in many different ways. In some cases a population is easily recognized as a group of individuals connected by gene flow, living in a continuous habitat and effectively isolated from any other groups of individuals of the same species. Gene flow exists within the population but is low or absent among the populations, although it might have been extensive in the past. Such a scenario is comparable with an isolated pond for aquatic species. However, in most cases it is much more difficult to define population boundaries and thus assess how many individuals constitute a population. For the purpose of this review we define a population very loosely as a group of individuals connected by gene flow that in recent times have occupied an approximately contiguous range. Commonly, such populations are defined in geographical terms corresponding to units such as a particular forest block, isolated forest fragment, or island.

How many individuals constitute a population?

Given a geographically defined or otherwise delimited population, a fundamental question concerns the number of individuals or social groups present. In addition, it is frequently of interest how many of these individuals are reproductively active and thus contribute to the next generation (i.e., the effective population size). Such questions not only reflect the innate interest of researchers in their study species but are also crucial for development and application of conservation and management plans. Especially in light of growing threats to many primate populations—35% of all primate species are threatened by extinction (IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group; website accessed on July 3, 2008), population dynamics, i.e. changes in population size over time, are of crucial interest.

Limitations of field-based population size estimates

Traditionally, field researchers have used individual identification or direct observations to assess the size of groups and populations (Collias and Southwick 1951; Chiarello 2000). If direct counts are impossible, because of factors such as the elusive nature of the species under study, challenging habitat, and the size of the area to be surveyed, indirect methods such as dung and nests counts, and track follows, are often used to estimate the population size (Aveling and Harcourt 1984; Fay 1991; Yamagiwa et al. 1993; Hashimoto 1995; Plumptre and Harris 1995; Gese 2001; Johnson et al. 2005; Morgan et al. 2006; Plumptre and Cox 2006). However, population surveys are complicated by the limitations of the methods used. Using direct observations, only a limited number of groups and/or individuals can be counted (Long et al. 1994), while most indirect methods require intensive and time-consuming field work prior to any attempts to census populations (Mathewson et al. 2008). For every traditional population size study there is the need to estimate “auxiliary variables”, for example:

-

construction/deposition and decay rates for nests and feces;

-

the influence of environmental factors, for example rainfall, on sign persistence;

-

vegetation identification, and evaluation of observer biases and detectability problems (Johnson et al. 2005; Marshall et al. 2006; Mathewson et al. 2008).

In addition, such studies have to be carried out separately for any new location and be randomly placed spatially, because important factors will differ and thus make population size estimates inaccurate and not comparable with one another (Laing et al. 2003; Kuehl et al. 2007; Mathewson et al. 2008). This is especially true if estimates from a small number of geographically restricted locations are extrapolated to bigger regions. In addition, even when carefully carried out, intrinsic limitations of estimates obtained by utilizing indirect methods may result in highly approximate numbers (Johnson et al. 2005; Mathewson et al. 2008). Accordingly, researchers are now beginning to use genetic methods to estimate animal population sizes, for example those of European otters (Arrendal et al. 2007), brown bears (Bellemain et al. 2005), pandas (Zhan et al. 2006), including primates (Guschanski et al. 2008a; Arandjelovic, unpublished data).

Molecular censusing

An advantage of molecular censuses is that noninvasive samples for genetic analysis, for example dung (Vigilant et al. 2001; Bergl and Vigilant 2007), hair (Goldberg and Wrangham 1997; Goossens et al. 2005), urine and saliva (Hayakawa and Takenaka 1999; Inoue et al. 2007), or extracts from discarded food items (Hashimoto et al. 1996), can be collected in parallel to field surveys (Guschanski et al. 2008a; Schubert, unpublished data) or opportunistically within the framework of other research activities in the area (Bellemain et al. 2005; Arandjelovic, unpublished data) (Fig. 1). This reduces the logistic and financial load. New advances in sample collection and storage methods (Nsubuga et al. 2004), extraction (Vallet et al. 2008), and molecular genotyping techniques (Lampa et al. 2008; Arandjelovic et al. 2008) using noninvasive samples enable rapid and efficient analysis of hundreds of samples (Lucchini et al. 2002; Banks et al. 2003; Creel et al. 2003; Nsubuga et al. 2004; Bellemain et al. 2005; Bergl and Vigilant 2007; Langergraber et al. 2007a; Puechmaille and Petit 2007). A complete mitochondrial genome was recently determined from fecal Propithecus (sifaka) samples (Matsui et al. 2007). Depending on the question of interest, the number of analyzed loci can be reduced to a minimum that is sufficient to discriminate between individuals, further reducing costs (Waits et al. 2001). Estimates of effective population size can be undertaken using genetic information (Schwartz et al. 1998) and thus close a gap left by traditional censusing techniques.

Flow chart of sample processing from collection to genotyping. For sample collection it is best to target fresh dung (less than 24 h old). For known individuals we recommend collection of two or three samples to confirm identity. Three methods of sample collection provide good results. If conditions allow, one can freeze the sample at −20°C or in liquid nitrogen. Because freezing is usually difficult in the field, collection in RNAlater or using the two-step collection method (Nsubuga et al. 2004) is recommended. Researchers interested in the study of pathogens may prefer to collect samples in RNAlater (Leendertz et al. 2006). Such samples, of course, also contain DNA of the study individual and can be used for population genetic studies (Eriksson et al. 2004). The two-step collection method has been successfully used for a variety of species (great apes, macaques, black-and-white colobus). We recommend collection of approximately 5 g (equivalent to a teaspoonful) of fresh dung and immersion in ~35 ml 90–99% ethanol. The ratio of dung to ethanol should be approximately 1:7; lower ratios can result in lower genotyping success. After storage in ethanol for 24 h, the sample is transferred on to silica beads for complete desiccation. Whatever method is used for sample collection, DNA is extracted from dung samples either using commercially available kits (Bradley et al. 2000) or by use of other extraction methods (Vallet et al. 2008). Multiplexing procedures can increase the speed and accuracy of genotyping and help to save the valuable genetic material by utilizing only small amounts of template (Lampa et al. 2008; Arandjelovic et al. 2008). Pictures are courtesy of K. Langergraber, R. Ikfuingei, T. Harris, and M. Arandjelovic

Recognizing the high potential of molecular survey methods, several statistical capture–mark–recapture programs developed in recent years can utilize genetic information for population size estimates (White and Burnham 1999; Eggert et al. 2003; Miller et al. 2005; Petit and Valiere 2006) and provide reliable results compared with actual population sizes (Puechmaille and Petit 2007) (Table 1). Some take into account that sampling for genetic censusing is usually carried out in a single session (Miller et al. 2005; Petit and Valiere 2006). Such collection procedures reduce the costs associated with coordinating sampling sessions.

In contrast with traditional censusing techniques, genetic censuses can be carried out everywhere sample collection is possible, without the need of intensive resource-consuming and time-consuming prior studies. Pilot studies are recommended when working with a new species or in a new habitat. Such studies are valuable for development of efficient sample collection, storage, extraction, and genotyping procedures, but will often be already in place from previous genetic studies on a given species. Thus, use of molecular census techniques will reduce time and effort and produce accurate population size estimates (Eggert et al. 2003; Zhan et al. 2006; Puechmaille and Petit 2007).

Valuable additional information is recovered by molecular censusing

Although the use of molecular techniques will increase the costs of projects aimed at population size estimates (note, however, that these costs can be dramatically reduced by new procedures, as in Table 2), it is important to mention that genotyping generates additional information that cannot be recovered from traditional surveys. For example, the sex ratio of the population can be estimated (Guschanski et al. 2008a; Banks et al. 2003) using markers amplifying homologous segments that differ in size between the X and Y chromosomes (Bradley et al. 2001; Di Fiore 2005; Villesen and Fredsted 2006). Such sex-ratio information is important as it gives insights into population growth capacities. For instance, a male-biased sex ratio in a population of the northern hairy-nosed wombat raised serious concerns about the population growth ability of this species (Banks et al. 2003). Even for unhabituated social groups, parentage of offspring can be assigned and thus variance in reproductive success estimated, as was done for mountain gorillas (Bradley et al. 2005; Nsubuga et al. 2008). This is, of course, facilitated if additional information exists on the age of individuals—in gorillas the diameter of the dung bolus is used as a proxy for age (Schaller 1963). The noninvasive samples collected during population censuses can also be used in endocrinological analyses for assessment of the reproductive status of females in the study population (Garnier et al. 1998; Jurke et al. 2000; Heistermann et al. 2008).

Recurrent molecular censuses not only offer insights into the dynamics of a given population or species but also help to identify important life history data and aspects of social structure through “molecular tagging” and subsequent tracking of individuals. This can enable researchers to follow individual animals for many years and potentially throughout their lives, infer individual movement through space and time, try to understand their dispersal decisions, and study their (lifetime) reproduction success.

Individual identification by genetic censusing has been suggested as an efficient and accurate method for monitoring of re-introduced primate populations (Goossens et al. 2003). It can be a valid alternative to time-consuming direct follows and to potentially dangerous and time-limited radio-collar tagging, thus reducing the need for human–animal interactions.

Population size dynamics

Whether obtained through field observation or genetic approaches, population size estimates only reflect the census population size, i.e. the number of individuals present in the population, and do not give any indication about the effective population size, Ne, i.e. the number of individuals needed in a theoretically ideal population to account for the level of variation observed in the actual sampled population (Wright 1931, 1938). This quantity is important as it reflects the long-term history of the population, and populations with small effective population sizes are thought to be at greater risk of extinction as a result of genetic effects (Frankham et al. 2002). For mammals the census size is generally expected to be 3–10 times higher than the effective population size (Frankham 1995; Storz et al. 2001). Factors such as overlapping generations, skew in reproductive success, unequal sex ratios, spatial or temporally structured populations—all of which typically characterize primate populations—complicate efforts to estimate Ne. Thus, researchers usually try, instead, to focus on specific questions such as whether a population has experienced a loss in diversity and whether such a loss was recent or more ancient.

Mitochondrial DNA studies

One of the most effective tools offering insights into trends in population sizes has been the rapidly evolving maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) molecule. It has been shown that for populations that have experienced an expansion in numbers, plots of the “mismatch distribution” showing the numbers of differences between pairs of mtDNA sequences, exhibit a peak, rather than a flat or irregular distribution (Rogers and Harpending 1992). Such a peak is characteristic of all human populations except non-agricultural populations (Excoffier and Schneider 1999). It is also observed in eastern chimpanzees (Goldberg and Ruvolo 1997) but not in other chimpanzee populations or in the bonobo (Gagneux et al. 1999), suggesting chimpanzee population histories have varied among different parts of Africa or that there is genetic substructuring in some chimpanzee populations.

Japanese macaques are particularly interesting for study because of their distribution across the archipelago over a wide range of environmental zones. Study of mtDNA sequences revealed that the variants in Japanese macaques are very similar to those in eastern rhesus macaques, and it is suggested that the split between the species occurred less than a million years ago (Marmi et al. 2004). In an impressively complete study, Kawamoto et al. (2007) analyzed mtDNA control region sequences from 135 individuals collected across the entire distribution of Japanese macaques. A tree relating all of the sequences showed two main clusters whose distribution corresponded to geography. Specifically, sequences of the A group were only found in eastern Japan whereas sequences of the B group were found in both eastern and western Japan. In addition, nucleotide diversity was higher for the B group sequences than for those of the A group, while the A (eastern) group showed signs of population expansion. These results suggest that Japanese macaques originated in the west and more recently expanded to the east; by effectively linking their data to faunal evidence the authors suggest that the expansion occurred in the last 15,000 years.

On a smaller geographic scale, Hayaishi and Kawamoto (2006) were able to use mtDNA to make inferences regarding the history of Japanese macaques on Yakushima Island. Island populations typically have low diversity in comparison with closely-related mainland populations, and so the finding of low diversity for the Yakushima Island monkeys was not surprising. However, these workers argue persuasively that the diversity found is too low to be attributed to a founder event tens or hundreds of thousands of years ago, and instead that the data suggest a bottleneck and subsequent expansion following a volcanic eruption some 7,000 years ago.

Nuclear DNA studies

Many primate species populations have been shown to have decreased in size in the last several hundred years as a result of human population growth and habitat exploitation. Field surveys and historical records suggest a dramatic reduction in population size of snub-nosed monkeys in the last 400 years (Li et al. 2002), mostly because of high human population growth, wars, deforestation, and hunting. By use of nest surveys, habitat loss and hunting pressure were shown to have had a dramatic effect on the orang-utan populations (Marshall et al. 2006). In recent years, newly developed approaches, for example simulation studies that utilize genetic information to reveal demographic scenarios that could have generated the observed genetic signature, have enabled researchers to look into the past and not only infer whether changes in population sizes have occurred but also to estimate the sizes of the ancestral populations and determine the time-point of population size changes. For example, several recent studies (Storz et al. 2002; Goossens et al. 2006) have used data from microsatellite genotyping to test whether reductions in population size can be attributed to climatic events, such as happened during the Pleistocene, or to more recent fragmentations associated with anthropogenic changes.

Storz et al. (2002) reasoned that whatever conditions allowed a late Pleistocene expansion of humans and eastern chimpanzees (see above) might have had a similar effect upon other co-distributed primates, such as the savannah baboon. However, analysis using a suite of microsatellite markers actually uncovered evidence of decline in the population savannah baboons of a factor of eight over the past 1,000–250,000 years, underscoring the variability of primate population dynamics. This decline was far too ancient to be attributed to anthropogenic effects. In contrast, a study on orang-utans from northeastern Borneo could clearly date the population collapse to recent heavy forest exploitation in this region in the last few decades (Goossens et al. 2006). Although fragmented forests were shown to still harbor quite large numbers of orang-utans (Marshall et al. 2006) and therefore have high conservation value, logging and, especially, hunting were identified as factors most strongly affecting orang-utan chances of survival.

Using autosomal microsatellite markers and Y-chromosome-specific microsatellite loci, Kawamoto et al. (2008b) studied the Shimokita macaques that occupy the northernmost range of the species. The small number of microsatellite alleles and Y-chromosomal haplotypes, low allelic and haplotypic richness, and an overall low level of genetic variability were consistent with the contemporary isolation of the Shimokita macaques from other macaque populations. However, the population was found to have gone through a bottleneck much earlier than could be attributed to the recent events of hunting and habitat destruction by humans. The authors suggest that during the post-glacial warming period that occurred approximately 5,000–10,000 years ago, the Shimokita population might have been isolated from other populations by rising sea levels. Additionally, human activities that began approximately 120 years ago seem to have led to a more recent bottleneck of this population.

Determining the origin of a population

A similar signature of heterozygosity loss consistent with a bottleneck was observed in an artificially introduced population of longtail macaques (Macaca fascicularis) in Mauritius (Kawamoto et al. 2008a). This species is thought to have been brought to Mauritius from Asia about four centuries ago by Dutch or Portuguese travelers. The origin of the maternal lineage was studied using mtDNA sequences and inferred to be most likely from Java. Another study confirmed the insular origin of the female lineage and further suggested that the Y-chromosomal haplotype was of continental origin from the Asian mainland (Tosi and Coke 2007). Interestingly, the only other macaque population that exhibits this unusual pattern of mtDNA/Y variants is the population from Sumatra. Tosi and Coke 2007 suggested that the mainland Y-haplotype was introduced to Sumatra during the late Pleistocene as the water level dropped and a land bridge formed between Malaysia and Sumatra, enabling male migration. In study of the origin of the Mauritius macaques two hypotheses were invoked to explain the discrepant mtDNA/Y pattern. First, the founders of the macaque population on the island of Mauritius could be a mixed stock including females from the Asian islands and males from mainland Malaysia. Second, because the Sumatran macaques exhibit the same pattern of mtDNA/Y diversity, the founders of the Mauritian populations might have come from Sumatra. In any event, after a bottleneck associated with a small number of founders, the macaques spread through the island of Mauritius. Although only two mtDNA haplotypes and a single Y-haplotype were found in this population, the autosomal diversity estimated using ten microsatellite loci was still quite high (Kawamoto et al. 2008a).

Another macaque study performed to reveal the origin of a population focused on the only macaque found in Africa, the Barbary macaque (Macaca sylvanus) (Modolo et al. 2005). Using mitochondrial DNA the workers analyzed the relationship between Moroccan and Algerian Barbary macaques and revealed a deep separation of the maternal lineage in these two populations. They also addressed the origin of the Gibraltar macaque population and found that both Moroccan and Algerian macaques contributed to this population.

Studies on the likely origin(s) of captive primate populations are useful for biomedical research, management of captive populations, establishment of breeding programs, and proper scientific design of reintroduction programs and conservation. For instance, in biomedical research the genetic background of study animals might affect their response to test conditions and it is thus very important to take it into consideration when designing experiments (Stevison and Kohn 2008; Satkoski et al. 2008).

Dating population events and estimating population size changes

With the possibility of using genetic information to estimate when changes in population size occurred and times of lineage divergence, researchers have a means to test hypotheses about which historical events may have played a key role in these changes. For example, by using mitochondrial and nuclear sequences, the first colonization of Madagascar by lemuriform primates was dated to approximately 62 Ma (Yoder and Yang 2004), much earlier than suggested by fossil records. This discrepancy can most likely be attributed to the fact that comprehensive fossil records of primate evolution are far too scarce (Fleagle 2002). The accelerated rate of radiation within the lemuriforms was dated to 42 Ma, a period of major changes in global climate, with turnover of marine and terrestrial biota and major extinction events. In a study on Yunnan snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus bieti), one of the 25 most endangered primates, researchers used sequences of the hypervariable region of mtDNA to show that the species went through a period of older population subdivision with subsequent range expansion and more recent anthropogenic fragmentation (Liu et al. 2007). The initial split was estimated to coincide with the late Cenozoic uplift of the Tibetan Plateau around 1.10–0.60 Ma, which caused great diversification of the plateau planes, probably producing boundaries between populations of snub-nosed monkeys. Similarly, secondary contact after initial subdivision was suggested for the black and gold howler monkey (Alouatta caraya), which occupies the southernmost range of any New World primate (Ascunce et al. 2007). For this species mtDNA control region sequences show a signal of population expansion, and this is thought to have occurred at the beginning of the Holocene, as the climatic conditions allowed the spread of forests.

Access to complete genome sequence information and new sequencing tools is enabling the use of DNA sequence data for more extensive investigations into primate population histories. For example, as a complement to description of the complete rhesus macaque genome (Gibbs et al. 2007), researchers performed additional “resequencing” of segments totaling more than 150 kb in nine and 38 rhesus macaques originating in China and India, respectively (Hernandez et al. 2007). The data suggest that the two populations split around 162,000 years ago and underwent strikingly different demographic changes, with the Chinese population subsequently tripling in size while the Indian population decreased by a factor of four.

Nuclear DNA sequence data from chimpanzees also suggest very different evolutionary histories for the different populations or subspecies, with a split between western and central chimpanzees as recently as ~500,000 years ago and a split between the chimpanzee and bonobo species only ~800,000 years ago (Fischer et al. 2004; Becquet and Przeworski 2007). Newer estimates based on vastly larger amounts of data from just a few individuals have refined those estimates, and suggest that the western chimpanzee population size has decreased while the central chimpanzee population has increased fourfold since their split (Caswell et al. 2008). Thalmann et al. (2007) demonstrated that even DNA from fecal samples can be used in a large-scale sequencing study by generating ~15 kb of sequence information from western and eastern gorillas. Since only a few eastern gorillas live in captivity, two were represented by samples of feces. A complex history for gorillas was inferred, with an initial split around 1 Ma but continuing gene flow until about 80,000–200,000 years ago.

Dispersal, gene flow and population structure

Dispersal, one of the main life history characteristics of a species, results in gene flow within and between populations. How individuals disperse across landscapes determines the genetic structure of the population and so is of great interest and importance, especially for threatened species. Estimates of population structure and connectivity are necessary for development of efficient conservation plans, definitions of conservation units and assignment of new conservation priority areas. Researchers and conservation managers are now interested in aspects of population isolation and in establishment of connectivity between populations to provide gene flow and thus increase the genetic diversity and potential viability of threatened and small populations. By assessing the genetic structure of a population much can be learned about factors favoring or restricting dispersal. Furthermore, by evaluating sex-specific markers or studying the genetic structure of sexes separately, researchers can make inferences about the species’ social system.

Insights from genetics into dispersal patterns and events

Dispersal events are difficult to observe, because they are rare and it is often impossible to monitor many individuals and groups simultaneously. Even in well studied populations for which data have been collected for many decades, dispersal can be observed only on a very limited spatial scale. Molecular tracking that allows monitoring of a much bigger area can help to solve this problem on the individual level. At the population level, researchers have been using molecular markers for many years to infer the extent, distance, and frequency of dispersal.

Dispersal in primates is mostly male-biased (Pusey and Packer 1987), with the prominent exceptions of the great apes and hamadryas baboons (Hammond et al. 2006), several New World monkeys (Symington 1988; Strier 1990), and red colobus (Struhsaker 1980). Thus, to examine the effects of sex-biased dispersal researchers often use sex-specific markers to reveal male and female dispersal histories (Melnick and Hoelzer 1992). Such markers have included mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA); more recently, identification of variable Y-specific markers in primates (Erler et al. 2004) has facilitated the study of male-mediated gene flow.

In apes, several studies compared patterns of variation revealed using the mtDNA molecule and the Y-chromosome. Results for bonobos and chimpanzees found the expected strong signal of male philopatry (Eriksson et al. 2006; Langergraber et al. 2007b). In recent years the X-chromosome is gaining popularity, at least in studies of humans, as an addition to the mtDNA to help uncover female population history (Schaffner 2004). Despite its great potential, no primate studies focused on inter-population comparisons have yet used this valuable marker.

When working with sex-specific markers, one has to keep in mind that the comparisons using these different genetic systems have to be made with caution, because of the different effective population sizes and effects of the species’ social system. Different levels of differentiation between male and female lineages, such as are inferred for human populations, have traditionally been interpreted as reflecting higher dispersal rates for one of the sexes (Seielstad et al. 1998). However, high variance in reproductive success for one of the sexes, typically the males, might have contributed to such a signal. When sex-specific markers are not available or as a complement, sex-biased dispersal can be studied using autosomal markers and comparing F ST values of pre-dispersed and post-dispersed individuals for each sex separately. This was demonstrated in a study of a population of hamadryas baboons, and results suggested recent evolution of female-biased dispersal in this species (Hammond et al. 2006).

In several primate species both sexes disperse, and thus the dispersal distance and frequency of each sex is of interest. When dispersal distances are small, direct observations might suffice to detect at least its presence and to estimate its rate. Transfers between neighboring groups that are habituated to human presence have been reported in black-and-white colobus (Harris 2009), mountain gorillas (Harcourt 1978), chimpanzees (Kawanaka and Nishida 1975), and baboons (Alberts and Altmann 1995), among others. However, when individuals disperse out of the study area the certainty that a dispersal event has occurred is much smaller. Genetic studies, by providing information from non-study animals through noninvasive sample collection, can potentially cover a much larger area than is possible with direct observations, and thus enable study of long-distance dispersal and uncover the fate of disappeared individuals. Long-distance dispersal was revealed in male Japanese macaques by linking the mtDNA haplotypes of adult males to social troops 45 km away from the study area (Yoshimi and Takasaki 2003). A recent study of western gorillas suggested that while both sexes disperse, males travel farther (Douadi et al. 2007). In animals not habituated to human presence, dispersal events can be detected by indirect monitoring through sample collection that is spaced over time. For example, transfers of females between groups were detected in western lowland and mountain gorillas, although no direct observations were possible (Arandjelovic, unpublished data; Guschanski, unpublished data).

Dispersal facilitates hybridization

Much work has focused on untangling the evolutionary histories of various macaque species. Among the first studies on gene flow within and among primate populations were studies by Japanese researchers using blood protein polymorphisms to infer the genetic structure of Japanese macaques throughout their range (Nozawa et al. 1982). However, subsequent analysis of restriction site polymorphism of mtDNA among the macaques produced results inconsistent with phylogenies derived from morphological and protein analyses (Morales and Melnick 1998). A study including some of the earliest assessments of Y-chromosome variation in primates compared Y-chromosome and mtDNA-derived phylogenies and suggested that male-mediated gene flow has complicated the histories of macaque species, with a possible hybrid origin of Macaca arctoides (Tosi et al. 2000). Such male-mediated introgression may not be exceptional, as a study of two Sulawesi macaque species found evidence of male-mediated gene flow across a narrow hybrid zone between M. maura and M. tonkeana (Evans et al. 2001) and gene flow also occurs between M. fascicularis and M. mulatta (Tosi et al. 2002).

Assessing and explaining genetic structure

Genetic structure is the presence of a detectable pattern of genetic subdivision within a sampled population. In primate populations, genetic structure can be induced by several factors, including population history and demography, social structure of the species, presence of dispersal barriers, differences in dispersal abilities, and individual habitat preferences. While demographical and historical effects on population structure have been discussed above, with population bottlenecks, expansions and secondary contact leaving a detectable genetic trace, we will now focus on the other aspects.

In order to study factors influencing genetic structure, the structure itself must first be assessed. In recent years, the biases that can be introduced by defining the population structure a priori, as is done for the classical AMOVA and other F ST-like-based approaches, have been recognized by many researchers (Pearse and Crandall 2004). Consequentially, new approaches have been developed that enable estimation of population subdivision by use of individual-based analysis (Pritchard et al. 2000; Falush et al. 2003; Corander et al. 2003, 2004; Francois et al. 2006) (Table 1). In recognition of the great effect that biotic and abiotic factors have on primates and other animals, landscape genetic approaches, which integrate population genetics, landscape ecology, and spatial statistics and thus allow assessment of the role of landscape variables on population structure, are now more frequently used (see Storfer et al. 2007 for an excellent review). In a further step, several software packages are now able to implement additional information on sampling location in the genetic structure analysis (Chen et al. 2007; Corander et al. 2008).

Dispersal barriers

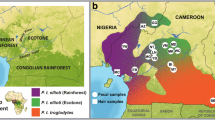

Whatever the method used, one long-standing preoccupation of studies of population structure is assessment of connectivity and isolation between different populations. For instance, habitat breaks, unsurpassable rivers, or mountain ridges are expected to negatively affect gene flow and thus result in genetic differentiation of populations. In humans, as in other primates, it seems that the pattern of genetic variation observed is largely consistent with isolation by distance, with some greater divisions corresponding to continental breaks (Rosenberg et al. 2005; Handley and Perrin 2007). Similarly, in a study of bonobos it was found that genetic distances estimated from mtDNA sequences increased with increasing geographical distances, but only when routes around impassable rivers were taken into account, suggesting that rivers and distance affect the genetic structure of bonobo populations (Eriksson et al. 2004). Recent work on another large-bodied ape, the orang-utan, has convincingly shown that rivers pose a barrier to gene flow on small and large geographical scales (Jalil et al. 2008). Other species for which river barriers seem to be important include, among others, gorillas (Anthony et al. 2007), chimpanzees (Gonder et al. 2006), and mouse lemurs (Guschanski et al. 2007). However, this is not always the case, and an effect of rivers was not detected in studies of spider monkeys (Collins and Dubach, 2000), long-tailed macaques (de Ruiter and Geffen 1998), and a number of lemur species (Pastorini et al. 2003; Craul et al. 2008).

If primate populations are isolated from each other by unfavorable habitat, for example human settlements, it is particularly difficult to assess the isolating effect of a presumed barrier. Although primates will usually avoid crossing such dangerous ground, the isolation might not be complete and some gene flow might still be present, as was shown for the highly endangered Cross River gorillas (Bergl and Vigilant 2007). Also, cryptic factors that might not be obvious to researchers will have an effect on gene flow and thus population structure. For instance, while animals may be capable of crossing areas of high elevation, they might prefer not to do so and thus limit gene flow between areas separated by mountains (e.g. mammals (Ernest et al. 2003; Rueness et al. 2003; Perez-Espona et al. 2008), birds (Hull et al. 2008), and amphibians (Funk et al. 2005; Spear et al. 2005). Human-induced savannahs and roads in Madagascar were shown to restrict gene flow between populations of mouse lemurs (Radespiel et al. 2008), resulting in diminished mtDNA diversity of populations inhabiting isolated forest fragments and in significant genetic isolation between populations (Guschanski et al. 2007).

Natal habitat preferences

Any preferences of individuals to remain in habitats familiar to them may affect genetic structure. Although natal habitat-biased dispersal is much discussed in the recent literature (Davis and Stamps 2004; Benard and McCauley 2008), it has been little applied to studies of primate populations (but see Murray et al. 2008; Radespiel et al. 2008; Guschanski et al. 2008b). Primates are as dependent as other animal species on a knowledge of their habitat. On the individual level, preference to forage in familiar habitats was shown for male chimpanzees (Murray et al. 2008). In this species, males are philopatric and their space use has often been explained by the distribution of females. However, when alone, male chimpanzees were shown to utilize areas in which they used to range when still dependant on their mother, suggesting the important role of habitat familiarity on individual space use. In chimpanzees and in gorillas, little is known about the factors emigrating females consider when choosing a new group. Recent work exploring the pattern of genetic variation in an entire population of mountain gorillas suggests that, in addition to social factors such as the number of males and females in the potential new group, female mountain gorillas may have a preference for groups ranging at a similar altitude and exploiting vegetation similar to that of their natal habitat (Guschanski et al. 2008b).

On the species level, different habitat preferences of sympatric species were shown for mouse lemurs, with the golden-brown mouse lemur (Microcebus ravelobensis) preferring low-altitude, humid habitats and the gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus) preferring higher altitudes and drier forest (Rakotondravony and Radespiel 2006). Furthermore, Microcebus ravelobensis showed a dispersal pattern that was consistent with dispersal along preferred habitats (Radespiel et al. 2008). Such habitat preferences would thus shape patterns of gene flow.

The presence of genetic structure within a continuous habitat, that might be puzzling at first, can thus be the result of unappreciated and cryptic habitat differences. If different habitats, even within a continuous landscape, have different degrees of permeability for primate species, dispersal may occur selectively along and into preferred habitats, resulting in substantial genetic structuring and high vulnerability to habitat breaks. In general, we suggest that natal habitat preferences will be increasingly recognized as playing an important role in affecting primate behavior on both the individual and population levels.

Landscape genetics

After population structure has been convincingly detected, the great challenge is then to assess the relative importance of different environmental factors, for example distance, habitat, temperature, different food resource availability, rainfall, and others, on the genetic structure. Several methods have been developed to help identify important factors. Traditionally, a multivariate Mantel test (Smouse et al. 1986) has been used in these cases. However, its applicability for different situations has recently been criticized (Raufaste and Rousset 2001; Rousset 2002). Now researchers increasingly use distance-based multivariate approaches (McArdle and Anderson 2001; Anderson 2004). Bayesian methods are also gaining popularity (Foll and Gaggiotti 2006; Faubet and Gaggiotti 2008) (Table 1). When evaluating habitat connectivity, new theoretical work, such as the isolation by resistance model that is based on the electric circuit theory (McRae 2006), provides a powerful tool that can simultaneously take into account multiple dispersal routes with varying degree of connectivity (McRae and Beier 2007).

Prospects for the near future

New sequencing technologies (Margulies et al. 2005; Bentley 2006) promise to have as big an effect on the scope of genome research as did the invention of PCR (polymerase chain reaction) some twenty years ago. These technologies allow a typical researcher to produce orders of magnitude more sequence information than was previously possible. By using information from the whole genome sequences that are being generated from primate and other animal species, we can target areas of the genome for resequencing. This ability to sample more of the genome will give us a much more representative view of genome wide variation, and this can improve inferences regarding population relationships and histories. Wild primate populations are often, of necessity, sampled using noninvasively obtained DNA, which is typically low in concentration, degraded, and mixed with large quantities of non-target DNA from food, bacteria, and random environmental contamination. Thus, the challenge to be overcome is the effective use of such DNA with these new approaches.

As mentioned above, study of gorilla, macaque, baboon, and even human and chimpanzee population histories (Patterson et al. 2006) suggests that periods of inter-species gene flow are typical in the past, or even in the present, for primate populations or species. More studies need to be conducted to determine whether it is usual for populations to split over a relatively short period of time, or whether complex scenarios involving long periods of gene flow are more typical, and to identify the factors affecting these transitions and the subsequent demographic histories of the daughter populations. Theoretical studies have discussed scenarios that would promote sympatric speciation (Doebeli and Dieckmann 2003) and we now have the opportunity to test these theoretical concepts. The complex scenarios revealed thus far remind us that the multidimensional patterns of variation and gene flow among populations make debating species definitions and classifications a futile undertaking (Jolly, 1993).

In this new era of genome sequencing, there are still many insights to be gained from studies using microsatellite loci to establish individually distinctive genotypes of hundreds of individuals. Steadily decreasing costs and increased efficiency of genotyping from noninvasively collected samples means that it is conceivable to assess hundreds or even a few thousand samples in a reasonable amount of time. As described above, these data can increase the precision of population census estimates and contribute additional information such as sex ratios, individual relationships, dispersal events, and individual monitoring. While much attention has been paid to the role of barriers in structuring genetic variation, less research has focused on the effects of valuable and attractive resources, for example bais for western lowland gorillas (Parnell 2002), water-holes for baboons (Hamilton et al. 1975), and high-sodium resources such as eucalyptus and aquatic vegetation for black-and-white colobus (Harris, personal communication; Oates 1978). Such attractants might reduce population genetic structure by attracting many social groups and promoting gene flow. This hypothesis can be tested by direct observations at these spots of attraction by evaluating the frequency of extra-group copulations or inter-group transfers. Subsequently it would be possible to genetically assess reproductive success, stability of group membership, and genetic structure in comparison with populations without such valuable resources. Another topic deserving attention in the near future includes the use of genetic data to identify asymmetrical patterns of gene flow typical of source-sink dynamics (Pulliam 1988). The understanding of these dynamics is important for evaluation of habitat quality and identification of dispersal corridors. This knowledge can in turn guide conservation efforts.

While working on this review we were encouraged to see the large number of recent high-quality studies using molecular approaches to study primate populations. We found numerous studies on great apes, our particular research focus, and on baboons, macaques, and lemurs. However, studies on other primate taxa are much less common, and comprehensive studies on a wider range of different populations and species of primates are needed. This is a challenge as funding for wild primate studies is not always easy to acquire. However, the importance of deepening our understanding of present and historic population dynamics, population sizes, and the factors that influence gene flow among populations remains unquestionable. This is especially true now while so many primate species are threatened by extinction and action needs to be taken to preserve them for future generations.

References

Alberts SC, Altmann J (1995) Balancing costs and opportunities: dispersal in male baboons. Am Nat 145:279–306

Anderson MJ (2004) DISTLM v.5: a FORTRAN computer program to calculate a distance-based multivariate analysis for a linear model. Department of Statistics, University of Auckland, New Zealand

Anthony NM, Johnson-Bawe M, Jeffery K, Clifford SL, Abernethy KA, Tutin CE, Lahm SA, White LJT, Utley JF, Wickings EJ, Bruford MW (2007) The role of Pleistocene refugia and rivers in shaping gorilla genetic diversity in central Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:20432–20436

Arandjelovic M, Guschanski K, Schubert G, Harris T, Thalmann O, Siedel H, Vigilant L (2008) Two-step multiplex PCR improves the speed and accuracy of genotyping using DNA from noninvasive and museum samples. Mol Ecol Res. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02387.x

Arrendal J, Vilà C, Björklund M (2007) Reliability of noninvasive genetic census of otters compared to field censuses. Conserv Genet 8:1097–1107

Ascunce MS, Hasson E, Mulligan CJ, Mudry MD (2007) Mitochondrial sequence diversity of the southernmost extant New World monkey, Alouatta caraya. Mol Phylogenet Evol 43:202–215

Aveling C, Harcourt AH (1984) A census of the Virunga gorillas. Oryx 18:8–13

Banks SC, Hoyle SD, Horsup A, Sunnucks P, Taylor AC (2003) Demographic monitoring of an entire species (the northern hairy-nosed wombat, Lasiorhinus krefftii) by genetic analysis of non-invasively collected material. Anim Conserv 6:101–107

Becquet C, Przeworski M (2007) A new approach to estimate parameters of speciation models with application to apes. Genome Res 17:1505–1519

Bellemain EVA, Swenson JE, Tallmon D, Brunberg S, Taberlet P (2005) Estimating population size of elusive animals with DNA from hunter-collected feces: four methods for brown bears. Conserv Biol 19:150–161

Benard MF, McCauley SJ (2008) Integrating across life-history stages: Consequences of natal habitat effects on dispersal. Am Nat 171:553–567

Bentley DR (2006) Whole-genome re-sequencing. Curr Opin Genet Dev 16:545–552

Bergl RA, Vigilant L (2007) Genetic analysis reveals population structure and recent migration within the highly fragmented range of the Cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli). Mol Ecol 16:501–516

Bradley BJ, Boesch C, Vigilant L (2000) Identification and redesign of human microsatellite markers for genotyping wild chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus) and gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) DNA from faeces. Conserv Genet 1:289–292

Bradley BJ, Chambers KE, Vigilant L (2001) Accurate DNA-based sex identification of apes using non-invasive samples. Conserv Genet 2:179–181

Bradley BJ, Robbins MM, Williamson EA, Steklis HD, Steklis NG, Eckhardt N, Boesch C, Vigilant L (2005) Mountain gorilla tug-of-war: silverbacks have limited control over reproduction in multimale groups. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:9418–9423

Caswell JL, Mallick S, Richter DJ, Neubauer J, Gnerre CSS, Gnerre S, Reich D (2008) Analysis of chimpanzee history based on genome sequence alignments. PLoS Genet. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000057

Chen C, Durand E, Forbes F, Francois O (2007) Bayesian clustering algorithms ascertaining spatial population structure: a new computer program and a comparison study. Mol Ecol Notes 7:747–756

Chiarello AG (2000) Density and population size of mammals in remnants of Brazilian Atlantic forest. Conserv Biol 14:1649–1657

Collias N, Southwick C (1951) A field study of population density and social organization in howling monkeys. Anat Rec 111:491–492

Collins AC, Dubach JM (2000) Biogeographic and ecological forces responsible for speciation in Ateles. Int J Primatol 21:421–444

Coltman DW, Bancroft DR, Robertson A, Smith JA, Clutton-Brock TH, Pemberton JM (1999) Male reproductive success in a promiscuous mammal: behavioural estimates compared with genetic paternity. Mol Ecol 8:1199–1209

Corander J, Siren J, Arjas E (2008) Bayesian spatial modeling of genetic population structure. Comput Stat 23:111–129

Corander J, Waldmann P, Marttinen P, Sillanpaa MJ (2004) BAPS 2: enhanced possibilities for the analysis of genetic population structure. Bioinformatics 20:2363–2369

Corander J, Waldmann P, Sillanpaa MJ (2003) Bayesian analysis of genetic differentiation between populations. Genetics 163:367–374

Craul M, Radespiel U, Rasolofoson DW, Rakotondratsimba G, Rakotonirainy O, Rasoloharijaona S, Randrianambinina B, Ratsimbazafy J, Ratelolahy F, Randrianamboavaonjy T, Rakotozafy L (2008) Large rivers do not always act as species barriers for Lepilemur sp. Primates 49:211–218

Creel S, Spong G, Sands JL, Rotella J, Zeigle J, Joe L, Murphy KM, Smith D (2003) Population size estimation in Yellowstone wolves with error-prone noninvasive microsatellite genotypes. Mol Ecol 12:2003–2009

Crispo E, Chapman LJ (2008) Population genetic structure across dissolved oxygen regimes in an African cichlid fish. Mol Ecol 17:2134–2148

Davis JM, Stamps JA (2004) The effect of natal experience on habitat preferences. Trends Ecol Evol 19:411–416

de Ruiter JR, Geffen E (1998) Relatedness of matrilines, dispersing males and social groups in long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis). Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 265:79–87

Di Fiore A (2003) Molecular genetic approaches to the study of primate behavior, social organization, and reproduction. Am J Phys Anthropol Suppl 37:62–99

Di Fiore A (2005) A rapid genetic method for sex assignment in non-human primates. Conserv Genet 6:1053–1058

Doebeli M, Dieckmann U (2003) Speciation along environmental gradients. Nature 421:259–264

Douadi MI, Gatti S, Levrero F, Duhamel G, Bermejo M, Vallet D, Menard N, Petit EJ (2007) Sex-biased dispersal in western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla). Mol Ecol 16:2247–2259

Eggert LS, Eggert JA, Woodruff DS (2003) Estimating population sizes for elusive animals: the forest elephants of Kakum National Park, Ghana. Mol Ecol 12:1389–1402

Eriksson J, Hohmann G, Boesch C, Vigilant L (2004) Rivers influence the population genetic structure of bonobos (Pan paniscus). Mol Ecol 13:3425–3435

Eriksson J, Siedel H, Lukas D, Kayser M, Erler A, Hashimoto C, Hohmann G, Boesch C, Vigilant L (2006) Y-chromosome analysis confirms highly sex-biased dispersal and suggests a low male effective population size in bonobos (Pan paniscus). Mol Ecol 15:939–949

Erler A, Stoneking M, Kayser M (2004) Development of Y-chromosomal microsatellite markers for nonhuman primates. Mol Ecol 13:2921–2930

Ernest HB, Boyce WM, Bleich VC, May B, Stiver SJ, Torres SG (2003) Genetic structure of mountain lion (Puma concolor) populations in California. Conserv Genet 4:353–366

Evans BJ, Supriatna J, Melnick DJ (2001) Hybridization and population genetics of two macaque species in Sulawesi, Indonesia. Evolution 55:1686–1702

Excoffier L, Heckel G (2006) Computer programs for population genetics data analysis: a survival guide. Nat Rev Genet 7:745–758

Excoffier L, Schneider S (1999) Why hunter-gatherer populations do not show signs of Pleistocene demographic expansions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:10597–10602

Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK (2003) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 164:1567–1587

Faubet P, Gaggiotti OE (2008) A new Bayesian method to identify the environmental factors that influence recent migration. Genetics 178:1491–1504

Fay JM (1991) An elephant (Loxodonta africana) survey using dung counts in the forests of the Central African Republic. J Trop Ecol 7:25–36

Fischer A, Wiebe V, Paabo S, Przeworski M (2004) Evidence for a complex demographic history of chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol 21:799–808

Fleagle JG (2002) The primate fossil record. Evol Anthropol 11:20–23

Foll M, Gaggiotti O (2006) Identifying the environmental factors that determine the genetic structure of populations. Genetics 174:875–891

Francois O, Ancelet S, Guillot G (2006) Bayesian clustering using hidden Markov random fields in spatial population genetics. Genetics 174:805–816

Frankham R (1995) Effective population size/adult population size rations in wildlife: a review. Genet Res Cambridge 66:95–107

Frankham R, Ballou JD, Briscoe DA (2002) Introduction to conservation genetics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Funk WC, Blouin MS, Corn PS, Maxell BA, Pilliod DS, Amish S, Allendorf FW (2005) Population structure of Columbia spotted frogs (Rana luteiventris) is strongly affected by the landscape. Mol Ecol 14:483–496

Gagneux P, Wills C, Gerloff U, Tautz D, Morin PA, Boesch C, Fruth B, Hohmann G, Ryder OA, Woodruff DS (1999) Mitochondrial sequences show diverse evolutionary histories of African hominoids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:5077–5082

Garnier JN, Green DI, Pickard AR, Shaw HJ, Holt WV (1998) Non-invasive diagnosis of pregnancy in wild black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis minor) by faecal steroid analysis. Reprod Fertil Dev 10:451–458

Garcia de Leaniz C, Fleming IA, Einum S, Verspoor E, Jordan WC, Consuegra S, Aubin-Horth N, Lajus D, Letcher BH, Youngson AF, Webb JH, Vollestad LA, Villanueva B, Ferguson A, Quinn TP (2007) A critical review of adaptive genetic variation in Atlantic salmon: implications for conservation. Biol Rev 82:173–211

Gese EM (2001) Monitoring of terrestrial carnivore populations. In: Gittleman JL, Funk SM, Macdonald D, Wayne RK (eds) Carnivore conservation (conservation biology 5). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 372–396

Gibbs RA, Rogers J, Katze MG, Bumgarner R, Weinstock GM, Mardis ER, Remington KA, Strausberg RL, Venter JC, Wilson RK, Batzer MA, Bustamante CD, Eichler EE, Hahn MW, Hardison RC, Makova KD, Miller W, Milosavljevic A, Palermo RE, Siepel A, Sikela JM, Attaway T, Bell S, Bernard KE, Buhay CJ, Chandrabose MN, Dao M, Davis C, Delehaunty KD, Ding Y, Dinh HH, Dugan-Rocha S, Fulton LA, Gabisi RA, Garner TT, Godfrey J, Hawes AC, Hernandez J, Hines S, Holder M, Hume J, Jhangiani SN, Joshi V, Khan ZM, Kirkness EF, Cree A, Fowler RG, Lee S, Lewis LR, Li ZW, Liu YS, Moore SM, Muzny D, Nazareth LV, Ngo DN, Okwuonu GO, Pai G, Parker D, Paul HA, Pfannkoch C, Pohl CS, Rogers YH, Ruiz SJ, Sabo A, Santibanez J, Schneider BW, Smith SM, Sodergren E, Svatek AF, Utterback TR, Vattathil S, Warren W, White CS, Chinwalla AT, Feng Y, Halpern AL, Hillier LW, Huang XQ, Minx P, Nelson JO, Pepin KH, Qin X, Sutton GG, Venter E, Walenz BP, Wallis JW, Worley KC, Yang SP, Jones SM, Marra MA, Rocchi M, Schein JE, Baertsch R, Clarke L, Csuros M, Glasscock J, Harris RA, Haviak P, Jackson AR, Jiang HY, Liu Y, Messina DN, Shen YF, Song HXZ, Wylie T, Zhang L, Birney E, Han K, Konkel MK, Lee JN, Smit AFA, Ullmer B, Wang H, Xing J, Burhans R, Cheng Z, Karro JE, Ma J, Raney B, She XW, Cox MJ, Demuth JP, Dumas LJ, Han SG, Hopkins J, Karimpour-Fard A, Kim YH, Pollack JR, Vinar T, Addo-Quaye C, Degenhardt J, Denby A, Hubisz MJ, Indap A, Kosiol C, Lahn BT, Lawson HA, Marklein A, Nielsen R, Vallender EJ, Clark AG, Ferguson B, Hernandez RD, Hirani K, Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Kolb J, Patil S, Pu LL, Ren Y, Smith DG, Wheeler DA, Schenck I, Ball EV, Chen R, Cooper DN, Giardine B, Hsu F, Kent WJ, Lesk A, Nelson DL, O’Brien WE, Prufer K, Stenson PD, Wallace JC, Ke H, Liu XM, Wang P, Xiang AP, Yang F, Barber GP, Haussler D, Karolchik D, Kern AD, Kuhn RM, Smith KE, Zwieg AS, Consortium RMGS (2007) Evolutionary and biomedical insights from the rhesus macaque genome. Science 316:222–234

Goldberg TL, Ruvolo M (1997) The geographic apportionment of mitochondrial genetic diversity in East African chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii. Mol Biol Evol 14:976–984

Goldberg TL, Wrangham RW (1997) Genetic correlates of social behaviour in wild chimpanzees: evidence from mitochondrial DNA. Anim Behav 54:559–570

Gonder MK, Disotell TR, Oates JF (2006) New genetic evidence on the evolution of chimpanzee populations and implications for taxonomy. Int J Primatol 27:1103–1127

Goossens B, Chikhi L, Ancrenaz M, Lackman-Ancrenaz I, Andau P, Bruford MW (2006) Genetic signature of anthropogenic population collapse in orang-utans. PLoS Biol 4:285–291

Goossens B, Chikhi L, Jalil MF, Ancrenaz M, Lackman-Ancrenaz I, Mohamed M, Andau P, Bruford MW (2005) Patterns of genetic diversity and migration in increasingly fragmented and declining orang-utan (Pongo pygmaeus) populations from Sabah, Malaysia. Mol Ecol 14:441–456

Goossens B, Setchell JM, Vidal C, Dilambaka E, Jamart A (2003) Successful reproduction in wild-released orphan chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes troglodytes). Primates 44:67–69

Griffin AS, Pemberton JM, Brotherton PNM, McIlrath G, Gaynor D, Kansky R, O’Riain J, Clutton-Brock TH (2003) A genetic analysis of breeding success in the cooperative meerkat (Suricata suricatta). Behav Ecol 14:472–480

Griffith SC, Owens IPF, Thuman KA (2002) Extra pair paternity in birds: a review of interspecific variation and adaptive function. Mol Ecol 11:2195–2212

Guschanski K, Olivieri G, Funk SM, Radespiel U (2007) MtDNA reveals strong genetic differentiation among geographically isolated populations of the golden brown mouse lemur, Microcebus ravelobensis. Conserv Genet 8:809–821

Guschanski K, Vigilant L, McNeilage A, Gray M, Kagoda E, Robbins MM (2008a). Counting elusive animals: comparing field and genetic census of the entire mountain gorilla population of Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda. Biol Conserv. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.10.024

Guschanski K, Caillaud D, Robbins MM, Vigilant L (2008b) Females shape the genetic structure of a gorilla population. Curr Biol 18:1809–1814

Hamilton WJ, Buskirk RE, Buskirk WH (1975) Chacma baboon tactics during intertroop encounters. J Mammal 56:857–870

Hammond RL, Handley LJL, Winney BJ, Bruford MW, Perrin N (2006) Genetic evidence for female-biased dispersal and gene flow in a polygynous primate. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 273:479–484

Handley LJL, Perrin N (2007) Advances in our understanding of mammalian sex-biased dispersal. Mol Ecol 16:1559–1578

Harcourt AH (1978) Strategies of emigration and transfer by primates, with particular reference to gorillas. Z Tierpsychol 48:401–420

Harris TR, Caillaud D, Chapman CA, Vigilant L (2009) Neither genetic nor observational data alone are sufficient for understanding sex-biased dispersal in social-group-living species. Mol Ecol (in press)

Hashimoto C (1995) Population census of the chimpanzees in the Kalinzu forest, Uganda: comparison between methods with nest counts. Primates 36:477–488

Hashimoto C, Furuichi T, Takenaka O (1996) Matrilineal kin relationship and social behavior of wild bonobos (Pan paniscus): Sequencing the D-loop region of mitochondrial DNA. Primates 37:305–318

Hayaishi S, Kawamoto Y (2006) Low genetic diversity and biased distribution of mitochondrial DNA haplotypes in the Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata yakui) on Yakushima Island. Primates 47:158–164

Hayakawa S, Takenaka O (1999) Urine as another potential source for template DNA in polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Am J Primatol 48:299–304

Heistermann M, Brauch K, Mohle U, Pfefferle D, Dittami J, Hodges K (2008) Female ovarian cycle phase affects the timing of male sexual activity in free-ranging Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) of Gibraltar. Am J Primatol 70:44–53

Hernandez RD, Hubisz MJ, Wheeler DA, Smith DG, Ferguson B, Rogers J, Nazareth L, Indap A, Bourquin T, McPherson J, Muzny D, Gibbs R, Nielsen R, Bustamante CD (2007) Demographic histories and patterns of linkage disequilibrium in Chinese and Indian rhesus macaques. Science 316:240–243

Hull JM, Hull AC, Sacks BN, Smith JP, Ernest HB (2008) Landscape characteristics influence morphological and genetic differentiation in a widespread raptor (Buteo jamaicensis). Mol Ecol 17:810–824

Inoue E, Inoue-Murayama M, Takenaka O, Nishida T (2007) Wild chimpanzee infant urine and saliva sampled noninvasively usable for DNA analyses. Primates 48:156–159

IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group, http://www.primate-sg.org

Jalil MF, Cable J, Inyor JS, Lackman-Ancrenaz I, Ancrenaz M, Bruford MW, Goossens B (2008) Riverine effects on mitochondrial structure of Bornean orang-utans (Pongo pygmaeus) at two spatial scales. Mol Ecol 17:2898–2909

Johnson AE, Knott CD, Pamungkas B, Pasaribu M, Marshall AJ (2005) A survey of the orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii) population in and around Gunung Palung National Park, West Kalimantan, Indonesia based on nest counts. Biol Conserv 121:495–507

Jolly CJ (1993) Species, subspecies, and baboon systematics. In: Kimbel WH, Martin LB (eds) Species, species concepts, and primate evolution. Plenum Press, New York, pp 67–107

Jolly CJ, Woolley-Barker T, Beyene S, Disotell TR, Phillips-Conroy JE (1997) Intergeneric hybrid baboons. Int J Primatol 18:597–627

Jurke MH, Hagey LR, Jurke S, Czekala NM (2000) Monitoring hormones in urine and feces of captive bonobos (Pan paniscus). Primates 41:311–319

Kawamoto Y, Kawamoto S, Matsubayashi K, Nozawa K, Watanabe T, Stanley MA, Perwitasari-Farajallah D (2008a) Genetic diversity of longtail macaques (Macaca fascicularis) on the island of Mauritius: an assessment of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms. J Med Primatol 37:45–54

Kawamoto Y, Shotake T, Nozawa K, Kawamoto S, Tomari K, Kawai S, Shirai K, Morimitsu Y, Takagi N, Akaza H, Fujii H, Hagihara K, Aizawa K, Akachi S, Oi T, Hayaishi S (2007) Postglacial population expansion of Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata) inferred from mitochondrial DNA phylogeography. Primates 48:27–40

Kawamoto Y, Tomari KI, Kawai S, Kawamoto S (2008b) Genetics of the Shimokita macaque population suggest an ancient bottleneck. Primates 49:32–40

Kawanaka K, Nishida T (1975) Recent advances in the study of inter-unit-group relationships and social structure of wild chimpanzees of the Mahale Mountains. In: Kondo S, Kawai M, Ehara A, Kawamura S (eds) The proceedings from the symposia of the 5th congress of the International Primatological Society. Japan Science Press, Nagoya, pp 173–186

Kuehl HS, Todd A, Boesch C, Walsh PD (2007) Manipulating decay time for efficient large-mammal density estimation: gorillas and dung height. Ecol Appl 17:2403–2414

Laing SE, Buckland ST, Burn RW, Lambie D, Amphlett A (2003) Dung and nest surveys: estimating decay rates. J Appl Ecol 40:1102–1111

Lampa S, Gruber B, Henle K, Hoehn M (2008) An optimisation approach to increase DNA amplification success of otter faeces. Conserv Genet 9:201–210

Langergraber KE, Mitani JC, Vigilant L (2007a) The limited impact of kinship on cooperation in wild chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:7786–7790

Langergraber KE, Siedel H, Mitani JC, Wrangham RW, Reynolds V, Hunt K, Vigilant L (2007b) The genetic signature of sex-biased migration in partilocal chimpanzees and humans. Plos One 10:1–6

Leendertz FH, Pauli G, Maetz-Rensing K, Boardman W, Nunn C, Ellerbrok H, Jensen SA, Junglen S, Boesch C (2006) Pathogens as drivers of population declines: the importance of systematic monitoring in great apes and other threatened mammals. Biol Conserv 131:325–337

Li BG, Pan RL, Oxnard CE (2002) Extinction of snub-nosed monkeys in China during the past 400 years. Int J Primatol 23:1227–1244

Liu Z, Ren B, Wei F, Long Y, Hao Y, Ll M (2007) Phylogeography and population structure of the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus bieti) inferred from mitochondrial control region DNA sequence analysis. Mol Ecol 16:3334–3349

Long YC, Kirkpatrick CR, Zhong T, Xiao L (1994) Report on the distribution, population, and ecology of the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus-Bieti). Primates 35:241–250

Lucchini V, Fabbri E, Marucco F, Ricci S, Boitani L, Randi E (2002) Noninvasive molecular tracking of colonizing wolf (Canis lupus) packs in the western Italian Alps. Mol Ecol 11:857–868

Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, Attiya S, Bader JS, Bemben LA, Berka J, Braverman MS, Chen YJ, Chen ZT, Dewell SB, Du L, Fierro JM, Gomes XV, Godwin BC, He W, Helgesen S, Ho CH, Irzyk GP, Jando SC, Alenquer MLI, Jarvie TP, Jirage KB, Kim JB, Knight JR, Lanza JR, Leamon JH, Lefkowitz SM, Lei M, Li J, Lohman KL, Lu H, Makhijani VB, McDade KE, McKenna MP, Myers EW, Nickerson E, Nobile JR, Plant R, Puc BP, Ronan MT, Roth GT, Sarkis GJ, Simons JF, Simpson JW, Srinivasan M, Tartaro KR, Tomasz A, Vogt KA, Volkmer GA, Wang SH, Wang Y, Weiner MP, Yu PG, Begley RF, Rothberg JM (2005) Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 437:376–380

Marmi J, Bertranpetit J, Terradas J, Takenaka O, Domingo-Roura X (2004) Radiation and phylogeography in the Japanese macaque, Macaca fuscata. Mol Phylogenet Evol 30:676–685

Marshall AJ, Nardiyono, Engstrom LM, Pamungkas B, Palapa J, Meijaard E, Stanley SA (2006) The blowgun is mightier than the chainsaw in determining population density of Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus morio) in the forests of East Kalimantan. Biol Conserv 129:566–578

Martin RD, Dixson AF, Wickings EJ (eds) (1992) Paternity in primates: genetic tests and theories. Karger, Basel

Mathewson PD, Spehar SN, Meijaard E, Nardiyono, Purnomo, Sasmirul A, Sudiyanto, Oman, Sulhnudin, Jasary, Jumali, Marshall AJ (2008) Evaluating orangutan census techniques using nest decay rates: implications for population estimates. Ecol Appl 18:208–221

Matsui A, Rakotondraparany F, Hasegawa M, Horai S (2007) Determination of a complete lemur mitochondrial genome from feces. Mammal Study 32:7–16

McArdle BH, Anderson MJ (2001) Fitting multivariate models to community data: a comment on distance-based redundancy analysis. Ecology 82:290–297

McRae BH (2006) Isolation by resistance. Evolution 60:1551–1561

McRae BH, Beier P (2007) Circuit theory predicts gene flow in plant and animal populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:19885–19890

Melnick DJ, Hoelzer GA (1992) Differences in male and female macaque dispersal lead to contrasting distributions of nuclear and mitochondrial-DNA variation. Int J Primatol 13:379–393

Miller CR, Joyce P, Waits LP (2005) A new method for estimating the size of small populations from genetic mark-recapture data. Mol Ecol 14:1991–2005

Modolo L, Salzburger W, Martin RD (2005) Phylogeography of Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) and the origin of the Gibraltar colony. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:7392–7397

Morales JC, Melnick DJ (1998) Phylogenetic relationships of the macaques (Cercopithecidae: Macaca), as revealed by high resolution restriction site mapping of mitochondrial ribosomal genes. J Hum Evol 34:1–23

Morgan D, Sanz C, Onononga JR, Strindberg S (2006) Ape abundance and habitat use in the Goualougo Triangle, Republic of Congo. Int J Primatol 27:147–179

Morin PA, Chambers KE, Boesch C, Vigilant L (2001) Quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of DNA from noninvasive samples for accurate microsatellite genotyping of wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus). Mol Ecol 10:1835–1844

Murray CM, Gilby IC, Mane SV, Pusey AE (2008) Adult male chimpanzees inherit maternal ranging patterns. Curr Biol 18:20–24

Nozawa K, Shotake T, Kawamoto Y, Tanabe Y (1982) Population genetics of Japanese monkeys. II. Blood protein polymorphisms and population structure. Primates 23:252–271

Nsubuga AM, Robbins MM, Boesch C, Vigilant L (2008) Patterns of paternity and group fission in wild multimale mountain gorilla groups. Am J Phys Anthropol 135:265–274

Nsubuga AM, Robbins MM, Roeder AD, Morin PA, Boesch C, Vigilant L (2004) Factors affecting the amount of genomic DNA extracted from ape faeces and the identification of an improved sample storage method. Mol Ecol 13:2089–2094

Nussey DH, Pemberton J, Donald A, Kruuk LEB (2006) Genetic consequences of human management in an introduced island population of red deer (Cervus elaphus). Heredity 97:56–65

Oates JF (1978) Water-plant and soil consumption by Guereza monkeys (Colobus guereza): a relationship with minerals and toxins in the diet? Biotropica 10:241–253

Olivieri G, Zimmermann E, Randrianambinina B, Rasoloharijaona S, Rakotondravony D, Guschanski K, Radespiel U (2007) The ever-increasing diversity in mouse lemurs: three new species in north and northwestern Madagascar. Mol Phylogenet Evol 43:309–327

Parnell RJ (2002) Group size and structure in western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) at Mbeli Bai, Republic of Congo. Am J Primatol 56:193–206

Pastorini J, Thalmann U, Martin RD (2003) A molecular approach to comparative phylogeography of extant Malagasy lemurs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:5879–5884

Patterson N, Richter DJ, Gnerre S, Lander ES, Reich D (2006) Genetic evidence for complex speciation of humans and chimpanzees. Nature 441:1103–1108

Pearse DE, Crandall KA (2004) Beyond FST: analysis of population genetic data for conservation. Conserv Genet 5:585–602

Perez-Espona S, Perez-Barberia FJ, McLeod JE, Jiggins CD, Gordon IJ, Pemberton JM (2008) Landscape features affect gene flow of Scottish Highland red deer (Cervus elaphus). Mol Ecol 17:981–996

Petit E, Valiere N (2006) Estimating population size with noninvasive capture–mark–recapture data. Conserv Biol 20:1062–1073

Plumptre AJ, Cox D (2006) Counting primates for conservation: primate surveys in Uganda. Primates 47:65–73

Plumptre AJ, Harris S (1995) Estimating the biomass of large mammalian herbivores in a tropical montane forest: a method of fecal counting that avoids assuming a ‘steady-state’ system. J Appl Ecol 32:111–120

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155:945–959

Puechmaille SJ, Petit EJ (2007) Empirical evaluation of non-invasive capture–mark–recapture estimation of population size based on a single sampling session. J Appl Ecol 44:843–852

Pulliam HR (1988) Sources, sinks, and population regulation. Am Nat 132:652–661

Pusey AE, Packer C (1987) Dispersal and philopatry. In: Smuts BB, Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM, Struhsaker TT, Wrangham RW (eds) Primate societies. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 250–266

Radespiel U, Rakotondravony R, Chikhi L (2008) Natural and anthropogenic determinants of genetic structure in the largest remaining population of the endangered golden-brown mouse lemur, Microcebus ravelobensis. Am J Primatol 70:860–870

Rakotondravony R, Radespiel U (2006) Regional biogeography of two sympatric mouse lemurs, Microcebus ravelobensis and M. murinus in the Ankarafantsika National Park, Madagascar. In: XXI Congress of the International Primatological Society. International Journal of Primatology, Entebbe, Uganda

Raufaste N, Rousset F (2001) Are partial mantel tests adequate? Evolution 55:1703–1705

Rocha LA, Bowen BW (2008) Speciation in coral-reef fishes. J Fish Biol 72:1101–1121

Rogers AR, Harpending H (1992) Population growth makes waves in the distribution of pairwise genetic differences. Mol Biol Evol 9:552–569

Rosenberg NA, Mahajan S, Ramachandran S, Zhao CF, Pritchard JK, Feldman MW (2005) Clines, clusters, and the effect of study design on the inference of human population structure. PLoS Genet 1:660–671

Rousset F (2002) Partial mantel tests: reply to Castellano and Balletto. Evolution 56:1874–1875

Rueness EK, Stenseth NC, O’Donoghue M, Boutin S, Ellegren H, Jakobsen KS (2003) Ecological and genetic spatial structuring in the Canadian lynx. Nature 425:69–72

Satkoski J, George D, Smith DG, Kanthaswamy S (2008) Genetic characterization of wild and captive rhesus macaques in China. J Med Primatol 37:67–80

Schaffner SF (2004) The X chromosome in population genetics. Nat Rev Genet 5:43–51

Schaller GB (1963) The mountain gorilla: ecology and behaviour. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Schwartz MK, Tallmon DA, Luikart G (1998) Review of DNA-based census and effective population size estimators. Anim Conserv 1:293–299

Seielstad MT, Minch E, Cavalli-Sforza LL (1998) Genetic evidence for a higher female migration rate in humans. Nat Genet 20:278–280

Smouse PE, Long JC, Sokal RR (1986) Multiple regression and correlation extensions of the mantel test of matrix correspondence. Syst Zool 35:627–632

Spear SF, Peterson CR, Matocq MD, Storfer A (2005) Landscape genetics of the blotched tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum melanostictum). Mol Ecol 14:2553–2564

Stevison LS, Kohn MH (2008) Determining genetic background in captive stocks of cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis). J Med Primatol 37:311–317

Storfer A, Murphy MA, Evans JS, Goldberg CS, Robinson S, Spear SF, Dezzani R, Delmelle E, Vierling L, Waits LP (2007) Putting the ‘landscape’ in landscape genetics. Heredity 98:128–142

Storz JF, Beaumont MA, Alberts SC (2002) Genetic evidence for long-term population decline in a savannah-dwelling primate: inferences from a hierarchical Bayesian model. Mol Biol Evol 19:1981–1990

Storz JF, Ramakrishnan U, Alberts SC (2001) Determinants of effective population size for loci with different modes of inheritance. J Hered 92:497–502

Strier KB (1990) New world primates, new frontiers: insights from the woolly spider monkey, or muriqui (Brachyteles arachnoides). Int J Primatol 11:7–19

Struhsaker TT (1980) The red colobus monkey. University of Chicago Press, Chicago