Abstract

We consider the role played by trade in differentiated inputs in the country-pair decision to form a PTA in goods and in their decision to expand it to trade in services with varying degrees of coverage, which transforms a preferential agreement into an Economic Integration Area (EIA). Our baseline model is very successful in predicting the formation of preferential agreements. Our model correctly predicts 84 percent of the country pairs with PTAs in our dataset and can successfully predict the 83 percent of the country pairs that do not form a PTA. Moreover, our model predicts 78 percent of the observations involving country pairs belonging to an EIA when a PTA exists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The dataset used in this paper will be available from the authors upon request.

Code availability

Our statistical analysis is based on a common software (Stata, version 16) used in the profession, and the code used to generate the results are available upon request.

Notes

The Post-WWII rules-based international trade system was established in part to avoid the "trade wars" and, more generally, the beggar-thy-neighbor policies that characterized the 1930 s. Douglas Irwin has recently discussed the fragmentation of the international economy during the 1930 s, and the main conclusions can be found at https://www.piie.com/experts/peterson-perspectives/trade-talks-episode-31-trade-wars-and-smoot-hawley-tariff-what-really.

In addition, the ninth round of negotiations initiated in Doha (Qatar) has failed to liberalize multilateral trade further.

The reader can check this information at http://rtais.wto.org/UI/charts.aspx. These figures correspond to physical agreements where double counting due to goods and service coverage and acceding processes is eliminated.

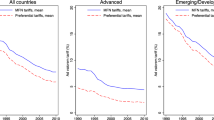

Nicita et al. (2018) argue that the combination of multilateral and preferential tariff reductions has led the average world exporter to face an average tariff of 2.6 percent. See details at https://voxeu.org/article/trade-war-will-increase-average-tariffs-32-percentage-points.

This definition follows the WTO. In particular, note that all country pairs with a preferential agreement covering some areas in services also have an agreement that involves goods, but, in many cases, preferential agreements only involve goods.

Researchers have investigated how preferential trade liberalization has affected multilateral tariffs and how it affects trade between member and non-member countries. Estevadeordal et al. (2008) and Limão (2006) consider whether lowering preferential tariffs tends to affect the MFN applied by Latin American economies and the multilateral tariff cuts negotiated by the U.S., respectively. Instead, Conconi et al. (2018) study the protectionist effects of the rules of origin used under the North American Free Trade Area (NAFTA) on the trade of intermediate products between members and non-members of that agreement.

Blanchard (2010) shows that the presence of FDI implies that the MFN and reciprocity rules do not completely control the negative effects of policy externalities across countries.

Bagwell et al. (2016) label these ideas as the Offshoring Theory of PTAs. More specifically, Antràs and Staiger (2012) argue that “...that in the presence of offshoring it is necessary to achieve “deep integration”-extending beyond a narrow market-access focus in ways that we formalize below-in order to arrive at internationally efficient policies.”

The WTO and IDE-JETRO (2011. pp. 15) use an example of a Japanese automaker outsourcing key components from four ASEAN countries (Malaysia, Philipines, Indonesia, and Thailand), taking advantage of the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA). More information regarding the example can be found in this publication by WTO and IDE- JETRO https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/stat_tradepat_globvalchains_e.pdf.

In this case, the Common Effective Preferential Tariff (AFTA-CEPT) applied by ASEAN members represents a cooperative arrangement among ASEAN member states to reduce intraregional tariffs and remove non-tariff barriers.

For instance, as part of the negotiations that led to the approval of the USMCA, Mexico received guarantees that its access to the U.S. automotive market would not change even if that country decided to impose additional tariffs on imports of cars from other WTO members. This strategy then implies that PTA formation can mitigate trade policy uncertainty. See side letter sent by the United States Trade Representative’s office to its Mexican counterpart at “https://ustr.gov/sites/default/_les/_les/agreements/FTA/USMCA/Text/MXUS Side Letter on 232.pdf."

Prusa and Teh (2010) explain that the formation of PTAs either rules out or significantly constrains the use of temporary trade barriers (Anti-dumping duties, countervailing duties, and safeguard measures) across member countries relative to the WTO negotiations. These agreements then decrease uncertainty relative to applying these measures as well. Tabakis and Zanardi (2019) show that PTA formation also leads to fewer applications of these tools against non-member countries by constraining these temporary trade measures of protection between members.

Information compiled from the WTO files provided at http://rtais.wto.org/UI/PublicAllRTAListAccession.aspx.

Of course, there are other essential papers in this literature. Notice that most articles tend to focus on the economic drivers of PTA formation with some notable exceptions. Liu and Ornelas (2014) focus on how the risk of interruption in a democratic regime may lead to an increase in the probability of PTA formation, which, in turn, tends to make democratic regimes last longer. On the other hand, Facchini et al. (2021) consider the political economy role of income inequality and trade imbalances on the decision to form a PTA and how geographic specialization of production affects the decision about PTA type (FTA or CU).

In this paper, we focus on free trade areas (FTAs) and customs unions (CUs) since these PTAs usually aim at implementing duty-free trade among members. As such, we do not use partial scope agreements as a PTA in testing the robustness of our results using data provided by Egger and Larch (2008) and Baier et al. (2014).

Egger et al. (2008) study how the endogenous formation of PTAs affects intra-industry trade. Instead, our focus is the effects of the bilateral share of trade on differentiated and differentiated-manufactured products, alongside interdependence, on PTA and EIA formation. Thus, our papers study different causalities and rely on different dependent and explanatory variables while we consider additional policy coverage across preferential agreements.

Egger and Shingal (2017) explore the role of the intensity of bilateral trade on goods and services in the formation of preferential agreements in services. They also consider the role of these variables in determining whether a preferential agreement in goods will be formed jointly or sequentially, given the decision to form an agreement in services. They find that the size of bilateral merchandising trade and bilateral trade in services are important determinants in forming preferential agreements.

Tsirekidze (2021) incorporates trade in inputs to the “competing exporters” model outlined in Bagwell and Staiger (1999). He shows that forming FTAs creates a free riding incentive for non-members countries due to lower tariffs on final goods while continuing their free-trade reliance on the non-member country for inputs. This result then makes free trade less likely as the importance of GVC (trade on inputs) grows. The paper then shows that sufficiently restrictive RoOs can be used to diminish this free-rider incentive, by shifting input demand towards FTA members. Thus, RoOs can be used as a policy device to increase the likelihood of free trade in equilibrium.

Likewise, Chen and Joshi (2010) use three-year time intervals for the same reason.

Mario Larch’s database defines that an EIA is present if the preferential agreement involves liberalization of service products included in the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). Details about his database can be found at https://www.ewf.uni-bayreuth.de/en/research/RTA-data/index.html. Instead, Baier et al. (2014) define the presence of unilateral trade agreements (e.g., GSP, African Growth and Opportunity Act, etc.), partial PTAs, FTAs, CUs, Common Markets, and Economic Unions. This dataset includes information for 195 country pairs from 1950 to 2012 and uses these six categories to provide information on the depth level of preferential liberalization between a country pair. Their dataset is available at https://sites.nd.edu/jeffrey-bergstrand/database-on-economic-integration-agreements/.

Hofmann et al. (2019) confirms this information.

Ornelas and Tovar (2022) investigate the decision to set preferential trade margins across FTAs and CUs. They explain that preferential tariffs are not necessarily set to zero because of PTAs created under the Enabling Clause, for instance. Their dataset focuses on several Latin American PTAs during the 1990s, where positive internal tariffs deviating from duty-free access across members were widespread.

According to the WTO’s Regional Trade Agreement Database, there are no countries pairs where an EIA exists for a country-pair, while it does not also share a PTA. In this case, only the European Economic Association (EEA) corresponds to a standalone EIA. However, notice that its members (Switzerland and the EU) have a separately negotiated FTA.

For comparison, the PTA database used in Baier et al. (2014) suggests that 7.5 percent of the total sample corresponds to country-pairs that belong to the same PTA.

Lake and Yildiz (2016) show that higher trade costs between members (distance) can turn CUs welfare-inferior relative to FTAs.

Mattoo et al. (2022) show that deep agreements lead to more trade creation and less trade diversion than shallow agreements.

This dataset is available at https://datatopics.worldbank.org/dta/table.html on the world bank site.

The dataset covers 52 policy areas and their legal enforceability in 279 PTAs among 189 countries up till 2015.

Osnago et al. (2019) find that the depth of trade agreements is correlated with vertical foreign direct investment. The relationship being positive when the provisions improve the contractibility of inputs provided by suppliers, and negative when these provisions relate to intellectual property rights and investment protection.

TRIMS covers Trade-Related Investment Measures that affect trade in goods. Hofmann et al. (2017) indicate that “These are provisions on requirements for local content and export performance on FDI and applies only to measures that affect trade in goods”. Moreover, TRIPS covers provisions that reinforce WTO commitments, including harmonization of standards and provisions related to intellectual property rights.

Investment under WTO-X relates to provisions on promotion, protection, and liberalization of investment measures or common investment policies, whereas IPRs includes any provision beyond that covered under TRIPS.

This dataset is available at https://econweb.ucsd.edu/~jrauch/rauch_classification.html

His commodity classification distinguishes among homogeneous (“w”), reference pricing (“r”), and differentiated goods (“n”). We use his code “n” to identify differentiated products.

The BEC labels intermediate goods as group “1”, final goods as group “2”, and capital goods as group “3”.

In this case, the average of \(RatioINP_{abt}\_diffman1\) for PTA country pairs is 32 percent higher than the equivalent average for the entire sample.

The only difference is that this measure focuses on the share of other country pairs with an EIA in place rather than a PTA.

Our baseline results use the two right-hand-side controls in expression (5) while applying our Probit with sample selection strategy. This strategy reflects limited information on determinants of policy related to services, investments, and IPR relative to the numerous literature on PTAs. Notice that we include all elements of matrix X in the latent equation (expression (5)) as a robustness test in Table 10 of the appendix.

This strategy controls for about 16500 fixed effects in total out of a sample of 69824.

For the interpretation:

-

1.

Margins in the table are: 0.0202 and 0.0315 for differentiated manufactured inputs with and without interdependence respectively.

-

2.

Standard deviation in the descriptive table is 0.202 manufactured differentiated inputs.

-

3.

Multiply the reported standard deviation with the marginal effects.

-

1.

We appreciate the suggestion made by referees to include this extension using Logit.

The lower the values of the AIC and SIC criteria the better the statistical performance.

We appreciate the suggestion made by a referee to include this extension of our results.

We appreciate the suggestion made by a referee to include this extension of our results.

Facchini et al. (2021) follow a similar approach.

Baldwin and Jaimovich (2012) follow a similar approach throughout their paper.

More information on E.U. is available at https://europa.eu/european-union/index_en.

References

Antràs, P., & Staiger, R. W. (2012). Offshoring and the role of trade agreements. American Economic Review, 102(7), 3140–3183.

Bagwell, K., Bown, C. P., & Staiger, R. W. (2016). Is the WTO passé? Journal of Economic Literature, 54(4), 1125–1231.

Bagwell, K., & Staiger, R. W. (1999). An economic theory of GATT. American Economic Review, 89(1), 215–248.

Baier, S. L., & Bergstrand, J. H. (2004). Economic determinants of free trade agreements. Journal of International Economics, 64(1), 29–63.

Baier, S. L., & Bergstrand, J. H. (2007). Do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade? Journal of international Economics, 71(1), 72–95.

Baier, S. L., Bergstrand, J. H., & Feng, M. (2014). Economic integration agreements and the margins of international trade. Journal of International Economics, 93(2), 339–350.

Baldwin, R., & Jaimovich, D. (2012). Are free trade agreements contagious? Journal of International Economics, 88(1), 1–16.

Bergstrand, J. H., & Egger, P. (2013). What determines bits? Journal of International Economics, 90(1), 107–122.

Blanchard, E. J. (2010). Reevaluating the role of trade agreements: Does investment globalization make the WTO obsolete? Journal of International Economics, 82(1), 63–72.

Chamberlain, G. (1980). Analysis of covariance with qualitative data. National Bureau of Economic Research: Technical report.

Chen, M. X., & Joshi, S. (2010). Third-country effects on the formation of free trade agreements. Journal of International Economics, 82(2), 238–248.

Cole, M. T., & Guillin, A. (2015). The determinants of trade agreements in services vs. goods. International Economics, 144, 66–82.

Egger, H., Egger, P., & Greenaway, D. (2008). The trade structure effects of endogenous regional trade agreements. Journal of International Economics, 74(2), 278–298.

Egger, P., & Larch, M. (2008). Interdependent preferential trade agreement memberships: An empirical analysis. Journal of International Economics, 76(2), 384–399.

Egger, P., & Shingal, A. (2021). Determinants of services trade agreement membership. Review of World Economics, 157(1), 21–64.

Egger, P. H., & Shingal, A. (2017). Granting preferential market access in services sequentially versus jointly with goods. The World Economy, 40(12), 2901–2936.

Estevadeordal, A., Freund, C., & Ornelas, E. (2008). Does regionalism affect trade liberalization toward nonmembers? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(4), 1531–1575.

Facchini, G., Silva, P., & Willmann, G. (2013). The customs union issue: Why do we observe so few of them? Journal of International Economics, 90(1), 136–147.

Facchini, G., Silva, P., & Willmann, G. (2021). The political economy of preferential trade agreements: An empirical investigation. The Economic Journal, 131(640), 3207–3240.

Fontagné, L., & Santoni, G. (2021). GVCs and the endogenous geography of RTAs. European Economic Review, 132, 103656.

Hofmann, C., A. Osnago, and M. Ruta (2017). Horizontal depth: a new database on the content of preferential trade agreements. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (7981).

Hofmann, C., Osnago, A., & Ruta, M. (2019). The content of preferential trade agreements. World Trade Review, 18(3), 365–398.

Horn, H., Mavroidis, P. C., & Sapir, A. (2010). Beyond the WTO? An anatomy of EU and US preferential trade agreements. The World Economy, 33(11), 1565–1588.

Johnson, R. C., & Noguera, G. (2017). A portrait of trade in value-added over four decades. Review of Economics and Statistics, 99(5), 896–911.

Laget, E., Osnago, A., Rocha, N., & Ruta, M. (2020). Deep trade agreements and global value chains. Review of Industrial Organization, 57, 379–410.

Lake, J., & Yildiz, H. M. (2016). On the different geographic characteristics of free trade agreements and customs unions. Journal of International Economics, 103, 213–233.

Limão, N. (2006). Preferential trade agreements as stumbling blocks for multilateral trade liberalization: Evidence for the United States. American Economic Review, 96(3), 896–914.

Liu, X., & Ornelas, E. (2014). Free trade agreements and the consolidation of democracy. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 6(2), 29–70.

Mattoo, A., Mulabdic, A., & Ruta, M. (2022). Trade creation and trade diversion in deep agreements. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne d’économique, 55(3), 1598–1637.

Mulabdic, A., Osnago, A., & Ruta, M. (2017). Deep integration and UK-EU trade relations. Springer.

Nicita, A., Olarreaga, M., & Silva, P. (2018). Cooperation in WTO’s tariff waters? Journal of Political Economy, 126(3), 1302–1338.

Ornelas, E., & Tovar, P. (2022). Intra-bloc tariffs and preferential margins in trade agreements. Journal of International Economics, 138, 103643.

Osnago, A., Rocha, N., & Ruta, M. (2019). Deep trade agreements and vertical FDI: The devil is in the details. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique, 52(4), 1558–1599.

Prusa, T. J., & Teh, R. (2010). Protection reduction and diversion: PTAs and the incidence of antidumping disputes. National Bureau of Economic Research: Technical report.

Rauch, J. E. (1999). Networks versus markets in international trade. Journal of International Economics, 48(1), 7–35.

Ruta, M. (2017). Preferential trade agreements and global value chains: Theory, evidence, and open questions. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (8190).

Subramanian, A., & Wei, S.-J. (2007). The WTO promotes trade, strongly but unevenly. Journal of International Economics, 72(1), 151–175.

Tabakis, C., & Zanardi, M. (2019). Preferential trade agreements and antidumping protection. Journal of International Economics, 121, 103246.

Tsirekidze, D. (2021). Global supply chains, trade agreements and rules of origin. The World Economy, 44(11), 3111–3140.

Van de Ven, W. P., & Van Praag, B. M. (1981). The demand for deductibles in private health insurance: A probit model with sample selection. Journal of Econometrics, 17(2), 229–252.

WTO (2011). The WTO and preferential trade agreements: From co-existence to coherence.

WTO and IDE-JETRO (2011). Trade patterns and global value chains in East Asia: From trade in goods to trade in tasks. WTO.

Funding

This paper has not benefited from any specific research grant or other extramural funding sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

We declare having NO ties with any institution that may have a policy interest in the topics addressed in this paper.

Consent for publication

We agree to publish this article in the Review of World Economics if its editorial board finds it suitable for publication

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

P. Silva: fellow at the GEP and Ld’A.

We are grateful for the excellent comments received by two referees and the associate editor, Frank Stähler. We also appreciate the seminar participants at the Fall 2020 Missouri Valley Economics Association, the Spring 2021 Midwest Economic Association, and the Fall 2022 Southern Economic Association annual meetings for their helpful comments and suggestions.

About this article

Cite this article

Ayub, K., Silva, P. Product differentiation, interdependence, and the formation of PTAs. Rev World Econ (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-023-00518-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-023-00518-0