Abstract

In this paper, we present empirical evidence that higher income inequality is associated with a greater equity share in countries’ external liabilities, and we develop a theoretical model that can explain this observation: In a small open economy with traded and non-traded goods, entry barriers depress entrepreneurial activity in non-traded industries and raise income inequality. The small number of domestic non-traded goods firms leaves room for foreign firms to operate on the domestic market, and it reduces external borrowing. The model thus suggests that barriers to entrepreneurial activity raise both inequality and the equity share in foreign liabilities. Our empirical results lend some support to this conjecture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

A broad consensus has emerged in the literature that the composition of foreign liabilities—that is, the relative shares of items such as foreign direct investment (FDI), portfolio equity, and external debt in a country’s external finance—is an important determinant of a country’s susceptibility to external crises. Given that liquidity crises are unlikely to be generated by sudden stops in equity flows but have often been triggered by sudden stops in debt flows, large external debt liabilities are usually associated with an increased crisis risk (Catão and Milesi-Ferretti, 2014). Moreover, the external capital structure of countries is seen as a determinant of economic performance, not least in light of the view that more desirable forms of finance such as FDI are associated with technological transfer. Notwithstanding the importance of countries’ external capital structure, previous work on understanding the factors underlying countries’ existing composition of external liabilities has been rather limited and mostly focused on the role of institutional quality and financial development.

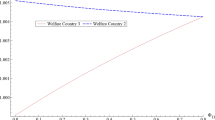

In this paper, we start by reporting an interesting empirical observation: Using data spanning the years 1996–2015, we find that higher income inequality is associated with a greater equity share in total external liabilities. Figure 1 illustrates the simple correlation between the (net) Gini index and the composition of external liabilities for a broad cross-section of countries. Our later regressions demonstrate that this relationship can be observed even if we control for a large range of factors including the quality of institutions.Footnote 1

Countries’ Gini coefficients of disposable income are taken from the Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID) and averaged over the years 1996–2015. The equity share—i.e. foreign direct investment and portfolio equity—in external liabilities is drawn from Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2018)

Income inequality and the equity share in countries’ external liabilities.

In a second step, we develop a theoretical model to explain this observation. Our key argument runs as follows: in a small open economy with traded and non-traded goods as well as unequally distributed wealth endowments, barriers to entry result in unequal access to entrepreneurial activity. More severe entry barriers lower per-capita income and enhance income inequality. While a lower per-capita income deters foreign firms, lower domestic entrepreneurial activity lowers external borrowing and provides an incentive for foreign firms to enter the domestic non-traded goods industries. We demonstrate that the latter effect dominates the former, such that higher inequality is associated with a higher equity share in external liabilities. In the third part of the paper, we demonstrate that a measure of entry barriers affects inequality and the equity share in the way predicted by the model.Footnote 2

The structure of this paper is as follows. In Sect. 2, we give a brief overview of the relevant literature and survey existing hypotheses regarding the potential determinants of countries’ external capital structure. In Sect. 3, we replicate some previous empirical studies on the determinants of countries’ external capital structure and demonstrate that several measures of inequality are strongly correlated with the equity share, even if we control for other factors. Section 4 presents our model, and Sect. 5 provides some evidence in support of our theoretical framework. Section 6 concludes.

2 Relevant literature

A generally accepted theory of what determines the composition of external liabilities across countries has not yet been developed. Some studies try to draw lessons from the corporate finance literature which extensively analyzes capital structures at the firm level (for instance Bolton and Huang, 2017). Others apply small open economy models with asymmetric information between countries (Razin et al., 1998) or draw on models from the contract-theory literature (Albuquerque, 2003). In this section, we briefly present existing theories and less formal hypotheses regarding the aggregate capital structure of nations.

Razin et al. (1998) adopt the framework by Gordon and Bovenberg (1996) to establish a pecking order of capital inflows in a model of asymmetric information (i.e. FDI, then external debt, and finally portfolio equity investment). Goldstein and Razin (2006) develop a model of FDI and foreign portfolio investment to explain the empirical observation that the share of FDI in total foreign equity inflows is larger for developing countries than for developed countries. Their model highlights the agency problem associated with portfolio investment projects as the key difference between the two types of investment. More specifically, direct investors are assumed to have an informational advantage that enables them to manage their projects more efficiently than foreign portfolio investors. At the same time, the firm owned by the FDI investor has a low resale price because of asymmetric information between the owner and the potential buyer leading to a key trade off between management efficiency and liquidity.

The theory by Albuquerque (2003) focuses on problems of expropriation and imperfect enforcement of international financial contracts to explain the finding that foreign direct investment is less volatile than other financial flows. He shows both theoretically and empirically that financially constrained countries have relatively larger inflows of FDI capital. The reason behind this finding is the intangible nature of a large share of direct investment (such as technology or a brand name) which makes it difficult to expropriate. Under this assumption, an optimal contract between international investors and financially constrained countries that are unable to credibly pre-commit not to expropriate will more likely take the form of FDI.

Wei and Zhou (2018) present a theoretical model that connects public governance to the capital structure of nations and firms. They do not only distinguish between equity and debt, but also focus on the maturity structure of the latter. In their framework, better institutional quality—and thus a better property rights protection—tends to promote a higher share of FDI and portfolio equity investment in total foreign liabilities, and a higher share of long-term debt within the debt category.

The empirical literature so far has largely focussed on the relationship between indicators of institutional quality and variables related to countries’ capital structures. Daude and Fratzscher (2008) test empirically for the existence of a pecking order of capital inflows and identify its determinants in a bilateral country-pair setting. They concentrate on the role of information frictions and the role of institutions as drivers of crossborder investment and find that portfolio investment is by far the most sensitive to the quality of institutions. However, the paper does not explore determinants of the ratio of equity and debt. Alfaro et al. (2008) focus only on FDI and show that the quality of institutions is a leading explanation behind the lack of investment flows from rich countries to poor ones. In a similar vein, Harms (2002) finds that political risk is an important determinant of the sum of foreign direct investment and portfolio equity investment per capita in developing countries. Hausmann and Fernandez-Arias (2000) find a negative relationship between FDI inflows to total private capital inflows and institutional quality, while Wei and Wu (2002) study the effect of corruption on the composition of capital inflows (FDI versus borrowing from foreign banks, in particular) and show that better institutions tilt capital inflows toward FDI and away from bank loans. Borensztein et al. (1998) argue that human capital may act as a “pull” factor for FDI but only when the host country has a minimum threshold stock of human capital. Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2000) examine the equity-to-debt ratio in total external liabilities and show that for developing countries trade openness is positively and significantly related. For industrial countries, the equity-debt-ratio has a strong positive relationship with stock market capitalization. Foreign exchange rate restrictions have a negative impact on the ratio among both groups of countries.

Our paper is most closely related to the (empirical) literature that explores the determinants of the equity share in countries’ total external liabilities. Faria et al. (2007) find that larger, more open economies with a better institutional quality score have a greater equity share in external liabilities. Moreover, natural resource production is also positively related to the equity share. In a similar vein, Faria and Mauro (2004, 2009) show that in a cross-section of advanced economies, emerging markets, and developing countries, equity-like liabilities as a share of countries’ total external liabilities are positively and significantly associated with indicators of educational attainment, openness, natural resource abundance and, especially, institutional quality. We contribute to this strand of literature by demonstrating that, in addition to the determinants identified by previous studies, measures of income inequality are systematically associated with the equity share in foreign liabilities.Footnote 3

3 Income inequality and the structure of countries’ external liabilities

3.1 Data definitions and sources

The data on our dependent variable—external liabilities and their subcomponents—is drawn from the “External Wealth of Nations” database by Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2018), which covers 212 economies for the period 1970–2015. External liabilities comprise foreign direct investment (FDI), portfolio equity, debt (consisting of portfolio debt, loans, currency, and deposits), and financial derivatives. In what follows, we define “total equity” as the sum of FDI and portfolio equity relative to total international liabilities.

Following the work of Faria and Mauro (2004, 2009), potential explanatory variables include the size of the economy (total GDP in trillions of USD at constant 2010 prices); the level of economic development (GDP per capita in thousands of USD at constant 2010 prices)Footnote 4; trade openness (sum of imports and exports over GDP); the importance of natural resources (share of exports of fuels, metals, and ores as a ratio of GDP); human capital (an index based on years of schooling and returns to education); financial development (the overall index from Svirydzenka, 2016)Footnote 5; and a measure of institutional quality (the simple average of six institutional indicators drawn from Kaufmann et al., 2010). Our novel contribution is to augment this specification by various measures of income inequality: the Gini coefficient of disposable income drawn from the Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID) by Solt (2016) as well as the share in total income allocated to the top 10% of earners and the share allocated to the bottom 20% of earners from the World Inequality Database. Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics for the variables used in this study.

Our baseline sample consists of the 119 countries—25 advanced and 94 emerging or developing, listed in the Appendix—for which all of our key explanatory variables are available (at least for one year between 1996 and 2015 for each country).Footnote 6 We follow the literature by eliminating offshore financial centers from the sample (28 countries).Footnote 7 The main reason for this is that much of the increase of FDI that started in the mid-1990s reflects not risk sharing or greenfield investment but claims on offshore financial centers driven by tax minimization strategies (see Lane and Milesi-Ferretti, 2018). More recently, Damgaard et al. (2019) estimate the decomposition of FDI into real FDI and Phantom FDI and argue that there is likely to be a structural limit to the amount of real FDI an economy can absorb. According to the authors, most FDI is thus likely to be Phantom FDI in economies where the ratio of total FDI to GDP is many times larger than usual. The countries in our final sample are unlikely to be hosts to a large share of Phantom FDI, since their ratio of total FDI to GDP is not very large and none of the usual suspects of Phantom FDI destinations that are identified in the literature (Casella, 2019) is part of our sample.

In terms of empirical specification, we follow the tradition in this literature by regressing the time-series mean of the dependent variable for the available years on the time-series means of the explanatory variables. Our baseline regression is thus equivalent to a between-estimator regression. We argue that this is consistent with our focus on the composition of liability stocks, and our interest in the fundamental, slow-moving, determinants of cross-country differences (see also Faria and Mauro, 2009).

Note that, at this stage, we do not take a stand on causality. Some scholars have indeed argued that capital inflows such as FDI might directly affect inequality—in particular by raising the skill premium given the apparent skill biases of international capital (see, for instance, Feenstra and Hanson, 1997, or Choi, 2006).Footnote 8 At the same time, Tsai (1995) finds that the relationship between FDI and inequality tends to vary significantly across geographical areas, and appears to be positive only in East and South Asian countries. Other studies have shown that the effect of FDI on inequality depends on absorptive capacity (Wu and Hsu, 2012) and the specific sector that absorbs FDI (Bogliaccini and Egan, 2017). Moreover, in contrast to there being a positive relationship, other scholars such as Milanovic (2005) and Sylwester (2005) argue that FDI has no impact on the income distribution. Hence, the literature on the relationship between inward FDI and income inequality is far from being conclusive. One reason might be that developing countries almost always implemented various liberalizing reforms concurrently, so that the distributional effects of trade liberalization become difficult to disentangle from other channels of internationalization, such as decreasing barriers to FDI (see Goldberg and Pavcnik, 2007). In spite of all this, it is important to note that empirical studies that find a positive relationship between FDI and inequality focus on the stock of FDI as a percentage of GDP—a measure relative to economic size. To the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence so far which suggests that the equity share in total external liabilities directly affects inequality.

3.2 Results

Table 2 presents the results of our cross-sectional regressions using the entire country sample. Column (1) replicates the studies of Faria and Mauro (2009) for the updated sample and documents that our results are qualitatively and quantitatively very similar to their findings: institutional quality, the abundance of natural resources, and openness are positively and significantly associated with the share of total equity in external liabilities. The size of the economy, human capital, and the level of financial development are also positively associated with total equity, though not always significantly. At the same time, the level of economic development is significantly negatively related to the equity share in total liabilities, suggesting that, with higher economic development, more and more debt-type instruments start to become available and marketable.

Starting in column (2), we add measures of inequality. All these variables are significantly correlated with the equity share or FDI in total external liabilities, with the Gini coefficient and the Top 10 income share exhibiting a positive relationship and the Bottom 20 income share a negative relationship. Note that we observe these relationships although we control for a host of other explanatory variables whose coefficients and significance levels are barely affected by the inclusion of the novel regressors.Footnote 9 Moreover, including measures of inequality substantially increases the explanatory power of the model, as indicated by the increase in \(R^2\) of up to ten percentage points. The magnitude of the coefficient is economically significant. For example, a country at the 75th percentile of the Gini index (say Thailand) would ceteris paribus exhibit an equity share that is 7.5 pp larger than a country at the 25th percentile (e.g. Estonia). Such an increase in total equity corresponds to about one quarter of the mean equity share in our sample (see Table 1).

Table 3 shows the results of the same regressions for the sample of non-high income countries. For this country group, economic size is significantly positively associated with total equity. The sign and magnitude of all estimated coeffcients remain largely unchanged compared to those for the whole sample. Moreover, the estimated coefficients of our inequality measures remain statistically significantly different from zero, with the only exception of the Top10 income share, which fails to meet standard levels of significance in column (6). Again, the coefficients of the other regressors barely change once we account for inequality.

4 A model of entry barriers, inequality, and foreign investment

4.1 Motivation

In the previous section, we have demonstrated that, in a large cross section of countries and over a fairly long time span, the share of equity in countries’ external liabilities is significantly associated with various measures of inequality, with more unequal countries being characterized by a higher equity share. In this section, we aim at explaining this observation by presenting a simple static model of a small open economy. The key ingredient of the model are barriers to entry, which hamper entrepreneurial activity in the economy’s non-traded goods sector. The fact that only a subset of agents can set up new firms gives rise to income inequality, which reflects the “entrepreneurial rent” earned by those individuals who manage to overcome those entry barriers. While reduced entrepreneurial activity depresses aggregate income and market size, it also produces a vacuum that generates an incentive for foreign firms to enter the domestic market. We show that, if the second effect dominates the first, more unequal countries are characterized not only by lower foreign borrowing, but also a greater presence of foreign firms, and thus a higher equity share in external liabilities.

4.2 Set-up and equilibrium

The small open economy we consider is populated by a continuum of individuals of mass one who consume a homogeneous traded and a bundle of non-traded goods.Footnote 10 The consumption aggregator for a representative individual is given by

\(C^{T}\) denotes the consumption of the traded good, whereas \(C^{N}\) is the consumption of non-traded goods, with \(\gamma\) being the expenditure share spent on the traded good. Utility derived from the consumption of non-traded goods is reflected by the CES aggregate

where \(c^{N}(i)\) denotes the consumption of variety i, \(\varepsilon > 1\) is the elasticity of substitution between different varieties, and \(\mu\) denotes the mass of non-traded goods, which will be endogenously determined within the model. The traded good serves as the numéraire and hence its price is normalized to one. Given the structure of preferences, we can easily derive the demand for non-traded good i as

where PC denotes the value of total consumption which equals domestic residents’ total income I, \(p^{N}(i)\) indicates the price of variety i, and P and \(P^{N}\) are the price indices of the total and the non-traded goods bundles, respectively.

Turning to the supply side of the economy, we assume that the traded goods sector is characterized by perfect competition, while monopolistic competition prevails in the non-traded goods sector. Production functions of traded and non-traded goods firms are linear in labor, with productivities denoted by \(a^{T}\) and \(a^{N}\), respectively.Footnote 11 These assumptions imply that the economy wide wage w equals \(a^T\), and that the marginal costs in the non-traded goods sector, denoted by \(MC^{N}(i)\), equal \(a^{T}/a^{N}\) for all varieties. Since each non-traded goods firm enjoys monopoly power for the variety it produces, it charges the price

where \(1/\alpha >1\) is the markup, which obviously decreases in the elasticity of substitution \(\varepsilon\).

Combining (3) and (4) and considering the fact that all non-traded goods firms face identical marginal costs and hence charge the same price, we can rewrite the demand for non-traded good i [Eq. (3)] as follows:

For given aggregate income PC, the demand for an individual non-traded good decreases in the (endogenous!) mass of non-traded goods \(\mu\).

Non-traded goods are produced by domestic firms and by foreign firms that do not differ with respect to their productivities. While domestic firms are run by domestic “entrepreneurs”, foreign firms in the domestic non-traded goods sector are part of multinational corporations (MNCs). We assume that, when setting up a non-traded goods firm, a domestic entrepreneur has to undertake an investment \(\kappa\) that is independent of the subsequent scale of production. Moreover, we assume that, for multinational corporations, this investment (\(\kappa ^F\)) is larger than for domestic entrepreneurs.Footnote 12 The assumption that \(\kappa ^F > \kappa\) can be justified by arguing that foreign firms have to spend additional resources on exploring domestic customs, rules and markets.Footnote 13

Our crucial assumption is that domestic agents differ with respect to their ability to set up a firm in the non-traded sector. More specifically, we assume that, at the start of the period considered, each domestic resident j is endowed with a wealth endowment v(j). The distribution of endowments in the domestic economy is described by the cumulative distribution function F(v) with density f(v), support \(\left[ v^{min},v^{max}\right]\) and \(v^{max}<\kappa\). An agent can rent her endowment to international capital markets at the exogenous world interest rate r.Footnote 14 Alternatively, she can become an entrepreneur, set up a non-traded goods firm, and use her capital in that firm. However, to set up a firm, an agent’s initial endowment has to exceed a critical value, i.e. \(v(j) \ge v^{crit}\). A straightforward way to rationalize this constraint would be to refer to financial market imperfections, but we prefer a broader interpretation that encompasses all kinds of prerequisites that are easier to satisfy for people with a larger wealth endowment.Footnote 15

If the income of an entrepreneur is higher than the wage rate, individuals with wealth endowments below the critical value \(v^{crit}\) become workers, while individuals with endowments equal or above \(v^{crit}\) become entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurial income, in turn, is given by the profits—revenues minus labor and capital costs—of a non-traded goods firm:

Note that the first part of this expression (revenue minus variable costs) is derived using Eqs. (4) and (5), and is the same for all non-traded goods firms, while capital costs depend on the entrepreneur’s endowment v(j).

Foreign non-traded goods firms (MNCs) do not face any entry barriers and can finance their capital costs by borrowing at the world interest rate r. As a consequence, MNCs enter the domestic non-traded goods market as long as their profits are non-negative. Free entry of MNCs implies that

Note that this condition illustrates the positive link between aggregate income PC—i.e. market size—and the mass of firms \(\mu\) that can co-exist in the domestic non-traded goods sector, i.e.

Equilibrium on the domestic labor market requires

where L depicts total domestic labor supply, implicitly determined by \(v^{crit}\), as that part of the population that does not engage in entrepreneurship, i.e. \(L=F(v^{crit})\). \(L^{T}\) represents the mass of individuals employed by domestic traded goods firms, and \(L^{N}\) the mass of individuals employed by non-traded goods firms (domestic firms and MNCs). Due to the symmetry in demand [see Eq. (5)] the labor demand of a domestic non-traded goods firm equals the labor demand of a foreign non-traded goods firm, and hence \(L^{N}=\mu L^{N}(i)\). The labor demand of a representative non-traded goods firm is given by

where the second equality follows from using Eqs. (4), (5) and (7). To determine the mass of foreign firms in the domestic non-traded goods sector, which we denote by \(\lambda\), we compute

where we have used Eq. (8). The mass of foreign non-traded goods firms equals the total mass of firms that fit into the market (at a given aggregate income level) minus the mass of domestic entrepreneurs, which is given by the share of the domestic population whose endowments exceed \(v^{crit}\), i.e. \([1-F(v^{crit})]\). Note that this equation illustrates the two crucial forces that determine the presence of foreign firms in the domestic non-traded goods sector: the domestic economy is an attractive location for MNCs if the market, as reflected by total income \(I = PC\), is large, and if there is a small number of domestic firms. Raising \(v^{crit}\) reduces the mass of domestic entrepreneurs, but also aggregate income. As we will show below, the first effect dominates the second.Footnote 16

The last task we have to accomplish to close the model is to compute total income. As a first step we calculate individual incomes of workers and entrepreneurs, respectively, and aggregate incomes in a second step. Income \(I^w(j)\) of individuals employed as workers with endowments \(v(j)<v^{crit}\) is given by

For individuals engaging in entrepreneurship with endowments \(v(j)\ge v^{crit}\) the income can be computed as

where the third equality follows from using Eq. (7). We can compare the two income levels to establish a condition that has to be satisfied to make entrepreneurial activity preferable to all those individuals that overcome the entry barrier. It is easy to show that this condition is given by

This expression requires that the “entrepreneurial rent” is strictly positive. We assume that this condition is satisfied. Combining the above expressions, we can compute aggregate income I (with \(PC=I\)) as

where \(\bar{v}\) denotes the average wealth endowment in the economy.

Note that our model turns ex-ante wealth inequality into ex-post income inequality since, regardless of their occupations, richer individuals earn a higher capital income rv(j). However, the separation into workers and entrepreneurs magnifies the original inequality if—as we assume—the entrepreneurial rent is positive. Moreover, if we interpreted v(j) as a (non-financial) endowment with entrepreneurial skills, which is unevenly distributed across individuals, we could interpret the model in a slightly different light: in this case, the entrepreneurial rent would be the only source of income inequality.

4.3 Comparative static analysis

In our model, entry barriers—as reflected by the threshold value \(v^{crit}\)—hamper entrepreneurship and hence depress the mass of non-traded goods firms run by domestic entrepreneurs. In the following we look at the implications for inequality on the one hand, and for the mass of MNCs, the volume of external borrowing, and the equity share in external liabilities on the other hand.

In order to characterize inequality in the economy we look at top and bottom income shares, respectively.Footnote 17 We investigate how changes in the mass of domestic entrepreneurs (implicitly defined by \(v^{crit}\)) affect these income shares. Let \({S}^H_{x}\) be the income share of the top \(x\%\) of the population. These are individuals with wealth endowments above some threshold \({v}^H_{x}\), which is implicitly defined by \(1-F({v}^H_{x})=x/100\). Assuming that \({v}^H_{x}\) lies above \(v^{crit}\) and using Eqs. (13) and (15) we can compute the top income share as follows:

The top income share increases in \(v^{crit}\), driven by a decrease in aggregate income. Hence, a decrease in the mass of domestic entrepreneurs increases the income share going to the top \(x\%\). Similarly, we look at the bottom income share and see how it is affected by changes in entrepreneurial activity. Let us define \({S}^L_y\) as the income share of the bottom \(y\%\). These are individuals with capital endowments below \({v}^L_{y}\), such that \(F({v}^L_{y})=y/100\). Again we assume that \({v}^L_y\) lies above \(v^{crit}\). Using Eqs. (12), (13) and (15), the bottom income share is given by

It is straightforward to show that the bottom income share decreases in \(v^{crit}\) since income of the bottom \(y\%\) declines by more than total income.Footnote 18 Thus, our model illustrates how unequal access to entrepreneurship gives rise to inequality.

As a next step, we look at the mass of MNCs, external borrowing and the equity share in external liabilities. Using Eq. (7) together with Eq. (15) in Eq. (11) we can compute the mass of MNCs in closed form as

As mentioned above, \(F(v^{crit})\) matters in determining the mass of MNCs for two reasons. On the one hand, \(F(v^{crit})\) is the share of individuals who do not become entrepreneurs. An increase in this share therefore increases the “open slot” for MNCs. On the other hand, \(F(v^{crit})\) affects aggregate income and thus the market size of the economy. Equation (15) reveals that aggregate income decreases in the share of individuals who do not become entrepreneurs. A lower market size leads to less MNCs ceteris paribus. It is easy to show that the term in curly brackets in Eq. (18) is greater than zero. Hence, the overall effect of \(v^{crit}\) on the mass of MNCs is positive, which implies that the “open slot” effect dominates the market size effect.

The equity share \(\rho\) in external liabilities is given by

where \(\lambda \kappa ^F\) denotes the amount of FDI and \(\int _{v^{crit}}^{v^{max}}(\kappa -v)f(v)\textrm{d}v\) measures the debt of domestic residents. An inspection of Eq. (19) reveals that the equity share increases in \(v^{crit}\).Footnote 19 Two channels contribute to this result. First, an increase in \(v^{crit}\) leads to more MNCs and therefore to more FDI. Second, an increase in \(v^{crit}\) reduces borrowing of domestic residents. Both effects lead to an increase in the equity share in external liabilities.Footnote 20

To sum up, our model establishes a positive link between income inequality and the equity share in external liabilities as suggested by the data, and provides a mechanism that may be driving this relationship. Figure 2 summarizes this mechanism. Entry barriers discourage entrepreneurship and lead to a decline in domestic entrepreneurial activity, which affects both the income distribution and the equity share. We show that income inequality increases. At the same time, there is more “room” for foreign firms to enter the market, and borrowing of domestic residents decreases. Both effects contribute to an increase in the equity share in external liabilities. Hence, the positive link between income inequality and the equity share is not due to the fact that one is directly causing the other. Instead, both inequality and the equity share are driven by entry barriers and their influence on entrepreneurial activity.

5 Entry barriers, inequality, and the composition of external liabilities

5.1 Taking the model to the data

In what follows, we will use the data set of Sect. 3 to explore whether the mechanisms outlined by our theoretical model have some empirical relevance. To do this, we will first demonstrate that barriers to entrepreneurial activity enhance inequality. In a second step, we will show that more severe entry barriers are associated with a higher equity share in foreign liabilities, as suggested by the model.

It goes without saying that, with its focus on horizontal investment in non-traded goods industries, our model does not exhaust all potential drivers of international assets and liabilities. However, in the presence of trade costs, the size of the domestic market should also be relevant for investment in traded goods industries. Moreover, as long as the forces we highlight in our model do not interfere with other determinants of the equity share in countries’ external liabilities, we should find them to be supported by the data.

Finally, recall that our sample comprises both developed and developing countries. Against the background of our model, this raises the questions (1) why rich countries have any equity-type liabilities at all, and (2) whether their equity share is driven by the forces specified in our model. To address the first question, we argue that, richer countries may, indeed, be less reliant on foreign multinationals to substitute for a lack of domestic entrepreneurial activity. In fact, the empirical results in Tables 2 and 3 indicate that per-capita GDP has a negative influence on the equity share. Nevertheless there may be an incentive for foreign firms to enter the market—for example, because foreign firms have a particular organizational or technical knowledge that lowers their costs. To address the second question, we argue that, even among rich countries, those that erect more severe barriers to domestic entrepreneurial activity encourage foreign multinationals to fill the void and thus attract more equity capital.

5.2 Entry barriers and inequality

Our model suggests that barriers to entrepreneurial activity are associated with greater inequality, raising top income shares and depressing bottom income shares. At the same time, depressed entrepreneurial activity reduces foreign borrowing and, by increasing the “residual market size” for foreign companies, raises FDI. This is reflected by a higher equity share in foreign liabilities. To explore whether the first part of this collection of hypotheses is supported by the data, we relate the measures of income inequality introduced above to the World Bank’s “Starting a Business” indicator. This indicator reflects “...the procedures, time and cost for an entrepreneur to start and formally operate a business, as well as the paid-in minimum capital requirement” (World Bank 2021). It is defined on a scale between 0 and 100, and increases as the environment for entrepreneurial activity becomes more favorable.Footnote 21 The World Bank has been publishing its indicator since 2004. However, the coverage for individual countries is very heterogeneous, with some large countries like the USA, Japan or India publishing data only for the immediate past. Moreover, the World Bank has frequently re-defined the criteria entering country assessments, and revised methods do not extend to all past periods.Footnote 22 Despite these shortcomings, we consider the World Bank’s “Starting a Business” indicator the best proxy for the threshold level \(v^{crit}\), with higher values of the indicator reflecting lower values of \(v^{crit}\). The binned scatterplots in Fig. 3 relate the average value of the “Starting a Business” indicator in the years 2011–2015 to two measures of inequality: the Top10 income share (panel a) and the Bottom20 income share (panel b). The patterns support the relationship postulated by our model: higher entry barriers—as reflected by a lower value of the “Starting a Business” indicator—raise the Top10 income share and depress the Bottom20 income share.

Binned scatterplot of the Top10 and Bottom20 income share, respectively, and the World Bank Starting a Business Score. The data of the Top10 and Bottom 20 income share is taken from the World Inequality Database (WID). The Starting a Business Score is taken from the World Bank Doing Business Database. All variables are time-series country-means for available years from 2011 to 2015

Barriers to Entry and Inequality.

5.3 Entry barriers and the equity share in external liabilities

In a next step, we explore the second part of our theoretical argument, i.e. whether domestic entry barriers—as reflected by the World Bank’s “Starting a Business” score affect the composition of countries’ external liabilities in the way suggested by our model. To achieve this goal, we re-run the regressions presented in Sect. 3, adding the World Bank’s score. If the channel highlighted by our model is empirically relevant, we should find a negative effect of the “Starting a Business” score on the equity share. Moreover, the effect of the inequality measures should be weakened or become insignificant.

For reasons outlined above, we cannot use the full time span underlying the regressions in Sect. 3. Instead, we compute averages for the years 2011–2015. In addition, we eliminate three countries, for which the “Starting a Business” score in 2015 deviates in an implausible manner from the 2011–2015 average.Footnote 23 As a robustness test, we will later consider this relationship only for the year 2015.

In Table 4, we start by re-estimating the specification of Sect. 3, using the Top10 income share (columns 1 and 4) and the Bottom20 income share (columns 7 and 9). We then replace the inequality measures by the “Starting a Business” score (columns 2 and 5). Finally, we include both a measure of inequality and the “Starting a Business” score (columns 3, 6, 8, 10). The results support the hypothesis that less (more) severe barriers to entrepreneurial activity have a negative (positive) effect on the equity share in foreign liabilities. Moreover, the effect of the “Starting a Business” score becomes weaker once we include the Top10 and Bottom20 income shares. The same holds true the other way around, i.e. the effect of the inequality measures gets diluted once we also account for barriers to entrepreneurial activity. Finally, the additional regressor improves the explanatory power of the model, as reflected by a higher adjusted \(R^2\). These results can be observed for the 2011–2015 averages (Table 4) and for the year 2015 (Table 5).

6 Conclusion

Several studies have shown that the composition of the stock of external liabilities correlates with the incidence of balance of payments crises and that a higher equity share in total liabilities reduces crisis susceptibility. In addition, more reliance on equity-like instruments (FDI and portfolio equity) is likely to be conducive to good economic performance not least given the fact that FDI is usually considered to enhance technology diffusion. It is thus very important to understand the factors underlying countries’ existing capital structures also with a view to formulate policies aimed at improving the composition of external liabilities. Attempts to explain the determinants of countries’ external capital structures have so far largely focussed on the role of institutional quality and financial development.

Our study has started by identifying a surprising correlation between measures of income inequality and the equity share in foreign liabilities. In our subsequent analysis, we have provided an explanation for this empirical result, highlighting the role of barriers to entrepreneurial activity for both income inequality and a country’s attractiveness for foreign equity investors and multinational corporations. Our theoretical framework does not imply that the relationship between inequality and the equity share is causal. Instead, both variables are driven by the severity of entry barriers. Our empirical analysis in the second part of the paper lends some support to this argument: in fact, the World Bank’s “Starting a Business” score is correlated with income inequality in the way suggested by the model. Moreover, adding this variable to cross-sectional regressions that seek to explain which factors determine the composition of external liabilities reveals that the equity share decreases as barriers to entrepreneurial activity become less severe in the domestic economy.

The result that a more favorable business environment reduces the equity share in foreign liabilities may come as a surprise. However, it is compatible with the logic of our model, which highlights the fact that domestic and foreign companies are competitors on the domestic market. While entry barriers may lower aggregate income and thus total market size, they also raise the “residual market size” for multinational companies.

In terms of normative conclusions and policy recommendations, our findings offer an important insight: Facilitating entrepreneurial activity, while reducing inequality and enhancing growth, may have problematic side effects by tilting the composition of countries’ foreign liabilities towards debt, which may generate undesirable macroeconomic vulnerabilities. There might thus be a case for accompanying the process of reducing entry barriers by appropriate macroprudential measures, targeted at limiting the risks arising from excessive foreign borrowing.

Notes

Our model implies that income inequality increases if entrepreneurial activity is concentrated in the hands of few. While the empirical literature on the relationship between entrepreneurship and inequality offers mixed evidence, a recent contribution by Halvarsson et al. (2018) documents that income dispersion increases if one focuses on those who are “self-employed in incorporated businesses”, as these entrepreneurs augment inequality from the top of the income distribution. Since this is exactly the type of entrepreneurship that our model has in mind—in contrast to those entrepreneurs for whom forced self-employment is an inferior alternative to regular employment—we think that our analysis rests on plausible empirical foundations.

While we focus on the composition of external liabilities rather than the total volume of net capital inflows, our contribution is also related to the—empirical and theoretical—literature that explores the influence of inequality on current account balances. As shown by Kumhof et al. (2012), Behringer and van Treeck (2018), and de Ferra et al. (2021), more unequal countries tend to run lower current account balances ceteris paribus. We share these contributions’ emphasis on the role of market frictions and complement them by an analysis of the equity share in external liabilities.

Our results remain unchanged if we use GDP converted to international dollars using purchasing power parity rates.

Svirydzenka (2016) creates nine indices that summarize how developed financial institutions and financial markets are in terms of their depth, access, and efficiency. These indices are then aggregated into an overall index of financial development. Our results are robust to alternative—and traditional—measures of financial development such as private credit to GDP, as recommended by Levine et al. (2000). The latter does, however, not take into account the complex multidimensional nature of financial development. Another advantage of our baseline measure of financial development is the large country coverage in the data.

Similar to Faria and Mauro (2009), we focus our analysis on two groups of countries: the whole sample includes countries at all levels of economic development while the sample of non-high-income countries consists only of developing and emerging economies.

Besides eliminating financial centers, the smaller size of our baseline sample compared to that of Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2018) is primarily owing to the availability of data on human capital and—to a lesser extent—on inequality.

In a similar vein, Basu and Guariglia (2007) investigate how the inflow of foreign capital impacts human capital inequality. They show that FDI could exacerbate inequality—particularly in an environment where some part of the population is unable to access the modern FDI-based technology because of low initial human capital.

As an alternative to our least squares regression, we also run a version of robust regressions in Stata. The results remain unchanged suggesting that our data is not contaminated with outliers or influential observations.

Assuming that the population size equals one enables us to identify aggregate with average values. None of our results—in particular, none of the ratios we will later derive—is affected by this assumption.

Note that we abstract from firm heterogeneity with respect to labor productivity, assuming that all firms within a given industry use identical production functions.

We assume the fixed investment to set up a firm in the rest of the world is sufficiently high for domestic firms such that they have no incentive to “go international”.

Note that our one-period model blurs the difference between the investment necessary to set up a firm and the eventual capital stock. A straightforward way to extend this to a multi-period environment is to assume that the capital stock completely depreciates within one period. Alternatively, we could argue that the per-period fixed costs are proportional to the underlying capital stock.

Assuming that this endowment cannot be directly lent to domestic borrowers spares us the task of modeling domestic financial markets. While this assumption has consequences for the country’s external assets and liabilities, it does not alter the key results derived below, as long as the economy’s foreign borrowing is positive.

A narrow focus on financial market imperfections would focus on an individual’s incentive to default on loans. For an individual with endowment v(j) that borrowed the amount \(\kappa -v(j)\) to finance entrepreneurial activity, defaulting would be attractive if \(r[\kappa - v(j)] \ge \xi\), with \(\xi\) reflecting the exogenous costs of a default. It is straightforward to show that, in this case, the minimum endowment necessary for entrepreneurial activity would be \(v^{crit} = \kappa - \xi /r\).

If we dropped our assumption that total population size equals one and replaced it by a population size of N, both \(\mu\) and \([1-F(v^{crit})]\) in Eq. (11) would be scaled up by N—the former, because total consumption spending would be average spending (PC) times N, the latter because the total number of entrepreneurs amounted to \([1-F(v^{crit})]N\). While a larger population size obviously results in a larger number of domestic and foreign firms, the ratio of domestic to foreign firms that we will later focus on is not affected by the size of N.

In the Appendix we also calculate the Gini coefficient characterizing the income distribution under the assumption that endowments are uniformly distributed.

If \({v}^L_y\) is smaller than \(v^{crit}\) we find that the bottom income share increases in \(v^{crit}\). In this case the numerator is unaffected by changes in \(v^{crit}\) since \({v}^L_{y}<v^{crit}\) by assumption. Hence, the effect is solely driven by the denominator, with aggregate income decreasing.

It is easy to show that this result would not change if we allowed domestic workers to directly lend to domestic entrepreneurs, i.e. if there were a domestic capital market. In this case, the denominator of Eq. (19) would read \(\lambda \kappa ^F+\int _{v^{crit}}^{v^{max}}\kappa f(v)\textrm{d}v - \bar{v}\), and the equity share \(\rho\) would increase in \(v^{crit}\) as long as foreign borrowing (\(\int _{v^{crit}}^{v^{max}}\kappa f(v)\textrm{d}v - \bar{v}\)) was non-negative.

We can tentatively link this result to the literature that analyzes the relationship between inequality and net capital inflows (Kumhof et al., 2012; Behringer and van Treeck, 2018; de Ferra et al., 2021). If we interpret the initial stock of wealth as domestic savings, it is easy to show that the difference between total domestic investment and domestic savings is given by \(\left[ 1 - F(v^{crit})\right] \kappa + \lambda \kappa ^{F} - \bar{v}\). Using Eq. (18) to characterize \(\lambda\), this can be transformed into \(\left[ (1-\gamma )(1-\alpha )-1\right] \left\{ \left[ 1-F(v^{crit})\right] (\kappa ^F-\kappa )+\bar{v}\right\} +F(v^{crit})(1-\gamma )(1-\alpha )a^T/r\). It is easy to show that this expression increases in \(v^{crit}\)—i.e., ceteris paribus, net capital inflows are increasing in the parameter that also drives income inequality.

More information on the “Starting a Business” indicator is given at https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/custom-query.

On the respective website, the World Bank informs that “in recent years, Doing Business introduced improvements to all of its indicator sets. In Doing Business 2015, getting credit and protecting minority investors broadened their existing measures. In Doing Business 2016, dealing with construction permits, getting electricity, registering property and enforcing contracts also introduced new measures of quality, and trading across borders introduced a new case scenario to increase the economic relevance. In Doing Business 2017, paying taxes introduced new measures of postfiling processes. Each methodology expansion was recalculated for one year to provide comparable indicator values and scores for the previous year. Rankings are calculated for Doing Business 2020 only. Year-to-year changes in the number of economies, number of indicators and methodology affect the comparability of prior years.”

These countries are Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo.

References

Albuquerque, R. (2003). The composition of international capital flows: Risk sharing through foreign direct investment. Journal of International Economics, 61(2), 353–383.

Alfaro, L., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., & Volosovych, V. (2008). Why doesn’t capital flow from rich to poor countries? An empirical investigation. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(2), 347–368.

Basu, P., & Guariglia, A. (2007). Foreign direct investment, inequality, and growth. Journal of Macroeconomics, 29(4), 824–839.

Behringer, J., & van Treeck, T. (2018). Income distribution and the current account. Journal of International Economics, 114, 238–254.

Bogliaccini, J. A., & Egan, P. J. W. (2017). Foreign direct investment and inequality in developing countries: Does sector matter? Economics and Politics, 29(3), 209–236.

Bolton, P., & Huang, H. (2017). The capital structure of nations (NBER Working Papers 23612). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J., & Lee, J.-W. (1998). How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics, 45(1), 115–135.

Casella, B. (2019). Looking through conduit FDI in search of ultimate investors—A probabilistic approach. Transnational Corporations, 26(1), 109–64.

Catão, L. A., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2014). External liabilities and crises. Journal of International Economics, 94(1), 18–32.

Choi, C. (2006). Does foreign direct investment affect domestic income inequality? Applied Economics Letters, 13(12), 811–814.

Damgaard, J., Elkjaer, T., & Johannesen, N. (2019). What is real and what is not in the global FDI network? (IMF Working Papers 19/274). International Monetary Fund.

Daude, C., & Fratzscher, M. (2008). The pecking order of cross-border investment. Journal of International Economics, 74(1), 94–119.

de Ferra, S., Mitman, K., & Romei, F. (2021). Why does capital flow from equal to unequal countries? (CEPR Discussion Papers 15647). Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Faria, A., Lane, P. R., Mauro, P., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2007). The shifting composition of external liabilities. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(2–3), 480–490.

Faria, A., & Mauro, P. (2004). Institutions and the external capital structure of countries (IMF Working Papers 04/236). International Monetary Fund.

Faria, A., & Mauro, P. (2009). Institutions and the external capital structure of countries. Journal of International Money & Finance, 28, 367–391.

Feenstra, R. C., & Hanson, G. H. (1997). Foreign direct investment and relative wages: Evidence from Mexico’s maquiladoras. Journal of International Economics, 42(3–4), 371–393.

Feenstra, R. C., Inklaar, R., & Timmer, M. P. (2015). The next generation of the Penn World Table. American Economic Review, 105(10), 3150–3182.

Goldberg, P. K., & Pavcnik, N. (2007). Distributional effects of globalization in developing countries. Journal of Economic Literature, 45(1), 39–82.

Goldstein, I., & Razin, A. (2006). An information-based trade off between foreign direct investment and foreign portfolio investment. Journal of International Economics, 70(1), 271–295.

Gordon, R., & Bovenberg, L. (1996). Why is capital so immobile internationally? Possible explanations and implications for capital income taxation. American Economic Review, 86(5), 1057–75.

Halvarsson, D., Korpi, M., & Wennberg, K. (2018). Entrepreneurship and income inequality. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 145, 275–293.

Harms, P. (2002). Political risk and equity investment in developing countries. Applied Economics Letters, 9, 377–80.

Hausmann, R., & Fernandez-Arias, E. (2000). Foreign direct investment: Good cholesterol? Research Department Publications 4203. Research Department: Inter-American Development Bank.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2010). The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues (Policy Research Working Paper Series 5430). The World Bank.

Kumhof, M., Lebarz, C., Rancière, R., Richter, A., & Throckmorton, N. (2012). Income inequality and current account imbalances (IMF Working Paper 12/08). International Monetary Fund.

Lane, P. R., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2000). External capital structure; Theory and evidence (IMF Working Papers 00/152). International Monetary Fund.

Lane, P. R., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2018). The external wealth of nations revisited: International financial integration in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. IMF Economic Review, 66(1), 189–222.

Levine, R., Loayza, N., & Beck, T. (2000). Financial intermediation and growth: Causality and causes. Journal of Monetary Economics, 46(1), 31–77.

Milanovic, B. (2005). Can we discern the effect of globalization on income distribution? Evidence from household surveys. World Bank Economic Review, 19(1), 21–44.

Razin, A., Sadka, E., & Yuen, C.-W. (1998). A pecking order of capital inflows and international tax principles. Journal of International Economics, 44(1), 45–68.

Solt, F. (2016). The standardized world income inequality database. Social Science Quarterly, 97(5), 1267–1281.

Svirydzenka, K. (2016). Introducing a new broad-based index of financial development (IMF Working Papers 16/5). International Monetary Fund.

Sylwester, K. (2005). Foreign direct investment, growth and income inequality in less developed countries. International Review of Applied Economics, 19(3), 289–300.

Tsai, P.-L. (1995). Foreign direct investment and income inequality: Further evidence. World Development, 23(3), 469–483.

Wei, S. -J., & Wu, Y. (2002). Negative alchemy? Corruption, composition of capital flows, and currency crises. In Preventing currency crises in emerging markets, NBER Chapters (pp. 461–506). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Wei, S. -J., & Zhou, J. (2018). Quality of public governance and the capital structure of nations and firms (NBER Working Papers 24184). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Wu, J.-Y., & Hsu, C.-C. (2012). Foreign direct investment and income inequality: Does the relationship vary with absorptive capacity? Economic Modelling, 29(6), 2183–2189.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper has benefited from helpful comments by Cian Allen, Geert Bekaert, Eleonora Cavallaro, Bernardo Fanfani, Robert Kollmann, and the participants at the 11th Ph.D. Workshop in Economics of the Collegio Carlo Alberto, Torino, participants at the 2019 INFER Workshop on “New challenges of economic and financial integration”, Bordeaux, participants at the “5th Mainz-Groningen workshop on FDI and Multinational Corporations”, Groningen, participants at the Brown Bag Seminar and the International Economics Workshop at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, participants at the European Trade Study Group Annual Conference, Ghent, participants at the 2022 Annual Conference of the Verein für Socialpolitik at Basel, and participants at an internal IMF Webinar. Finally, the insightful comments of an anonymous referee helped to substantially improve the paper. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Bundesbank or the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Sources and description of the variables

1.1.1 Dependent variables

The source for countries’ total external liabilities and their components in the baseline regressions (FDI, portfolio equity and debt) is the data set developed by Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2018). All variables are in millions of U.S. dollars. Data are available at http://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/WP/2017/datasets/wp115.ashx.

The dependent variables are expressed as ratios to total liabilities. The dependent variables used in the baseline regressions and in most specifications are, unless otherwise noted, a time-series mean of the variables of interest between 1996 and 2015, whenever available.

1.1.2 Independent variables

Gini coefficient

Gini index of disposable income for all available years between 1996 and 2015. Source:The Standardized World Income Inequality Database (SWIID) developed by Solt (2016), https://fsolt.org/swiid/.

Top10 income share

Share in pre-tax national income allocated to the top 10% of earners. Source: World Inequality Database, https://wid.world/.

Bottom20 income share

Share in pre-tax national income allocated to the bottom 20% of earners. Source: World Inequality Database, https://wid.world/.

Institutional quality index

Following Faria and Mauro (2009), the institutional quality index is constructed as the average of six institutional indicators (voice and accountability, political stability and absence of violence, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, control of corruption), drawn from Kaufmann et al. (2010), for all available years between 1996 and 2015 (available for 1996, 1998, 2000, and annually from 2002 on). The institutional quality index in a given year is formed only for countries that have information for all governance indicators in that year. Source: Worldwide Governance Indicators, www.govindicators.org.

Gross domestic product

Constant 2010 U.S. dollars for all available years between 1996 and 2015. Rescaled to trillions in the regressions to make results more legible. Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/.

GDP per capita

GDP per capita in constant 2010 U.S. dollars for all available years between 1996 and 2015. Rescaled to thousands in the regressions to make results more legible. Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/.

Financial development

Overall index of financial development for all available years between 1996 and 2015 drawn from Svirydzenka (2016). The index summarizes how developed financial institutions and financial markets are in terms of their depth, access, and efficiency. Source: Financial Development Index Database, IMF, https://www.imf.org/~/media/Websites/IMF/imported-datasets/external/pubs/ft/wp/2016/Data/_wp1605.ashx.

Natural resources

Percentage of ore, metals and fuels in total exports for all available years between 1996 and 2015. Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/.

Openness

Sum of imports and exports divided by total GDP for all available years between 1996 and 2015. Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/.

Human capital

Human capital index based on years of schooling and returns to education for all available years between 1996 and 2014. Source: Feenstra et al. (2015) available from Penn World Table version 9.0, https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/productivity/pwt/.

Starting a business indicator

Indicator published by the World Bank measuring how favorable the environment in a country is for entrepreneurial activity. Source: Doing Business Indicators, World Bank, https://www.doingbusiness.org.

Countries

The baseline sample used in the regressions consists of the following 119 countries: Albania, Algeria, Angola, Argentina, Armenia, Australia*, Austria*, Bangladesh, Belize, Benin, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cambodia, Cameroon, Canada*, Central African Rep., Chile, China, Colombia, Congo, Costa Rica, CÃ’te d’Ivoire, Croatia, Czech Republic*, Denmark*, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Estonia*, Ethiopia, Fiji, Finland*, France*, Gabon, The Gambia, Germany*, Ghana, Greece*, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Hungary, Iceland*, India, Indonesia, Iran, Israel*, Italy*, Jamaica, Japan*, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Korea*, Kuwait, Kyrgyz Republic, Latvia*, Lesotho, Lithuania*, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Mali, Mauritania, Mexico, Moldova, Mongolia, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, New Zealand*, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Norway*, Pakistan, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal*, Qatar, Romania, Russia, Rwanda, Senegal, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Slovak Republic*, Slovenia*, South Africa, Spain*, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Swaziland, Sweden*, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Thailand, Togo, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United States*, Uruguay, Venezuela, Vietnam, Yemen, Zambia.

Countries marked with * are excluded from the non-high income sample. The classification of countries according to the income level follows from Appendix 1 in Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2018).

We exclude from the sample all countries considered offshore financial centers (as listed in Lane and Milesi-Ferretti, 2018): Andorra, Bahamas, Bahrain, Barbados, Belgium, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Cayman Islands, Macao (S.A.R. of China), Curacao, Cyprus, Gibraltar, Guernsey, Hong Kong (S.A.R. of China), Ireland, Isle of Man, Jersey, Luxembourg, Malta, Mauritius, Netherlands, Netherlands Antilles, Panama, San Marino, Singapore, Switzerland, Turks and Caicos, United Kingdom.

1.2 Deriving and analyzing the model-implied Gini coefficient for a uniform distribution

To calculate the Gini coefficient characterizing the income distribution let us assume that endowments are uniformly distributed with \(v\sim \mathcal {U}\left[ v^{min},v^{max}\right]\), the cumulative distribution function \(F(v)=\frac{v-v^{min}}{v^{max}-v^{min}}\), and density \(f(v)=\frac{1}{v^{max}-v^{min}}\). The Gini coefficient characterizing the distribution of endowments is given by

with the following properties: \(\partial Gini(v)/\partial v^{max} >0\) and \(\partial Gini(v)/\partial v^{min} <0\). The distribution of endowments translates into the distribution of income. In order to derive the Gini coefficient characterizing the distribution of income we first compute income shares. If \(v<v^{crit}\), the share \(S_{1}(v)\) of total income I received by agents with \(v(j)\le v\) is given by

If \(v\ge v^{crit}\), the share \(S_{2}(v)\) of total income I received by agents with \(v(j)\le v\) is given by

Transforming these shares into functions of F yields

for \(F<F(v^{crit})\) and

for \(F\ge F(v^{crit})\). The Gini coefficient can then be computed as

Equation (25) can be rewritten to get

where \(\Gamma\) is a function of \(F(v^{crit})\), i.e.

It is straightforward to show that a sufficient condition for \(\textrm{d}\Gamma /\textrm{d}F(v^{crit})<0\) is \(F(v^{crit})\le \hat{F}(v^{crit})\) with

We hence show that under mild conditions, i.e. for values of \(F(v^{crit})\) below some threshold with the threshold being above 1/2, the Gini coefficient characterizing the income distribution is increasing in the share of individuals who do not become entrepreneurs.

Let us also look at the mass of MNCs, external borrowing and the equity share in external liabilities under the assumption that endowments are uniformly distributed. The mass of MNCs can be computed as

As discussed in Sect. 4.3 the mass of MNCs increases in the critical endowment level \(v^{crit}\) reflecting the fact that lower domestic entrepreneurial activity attracts foreign firms. The implications for the equity share are as follows:

It is straightforward to see that the equity share increases in \(v^{crit}\) since a lower mass of domestic entrepreneurs attracts foreign equity and reduces borrowing.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Harms, P., Hoffmann, M., Kohl, M. et al. Inequality and the structure of countries’ external liabilities. Rev World Econ 160, 585–613 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-023-00499-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-023-00499-0