Abstract

We develop a three-stage lobbying game to explain why the WTO prohibits export subsidies but not import tariffs. In this model, the government chooses trade policies (i.e., import tariffs or export subsidies) to maximize a weighted sum of social welfare and lobbying contributions. We argue that the economic rents from export subsidies cannot be contained exclusively within lobby groups, because new capitalists, who will enter the growing export sector, freely benefit from export subsidies without paying political contributions at the time of lobbying. In the contracting import-competing industries, no new entrants erode the protection rents from tariffs. Therefore, the government receives large political contributions by protecting these import-competing industries. We show that, given that capital reallocation is costly, when the free-rider problem is severe, the government will sign a trade agreement that prohibits only export subsidies. In the extended model in which the government has a continous policy space, we show that there is a non-empty set of parameter values such that the government would prohibit export subsidies while allowing for positive tariffs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

An agreement is considered complete if it specifies the exact levels of tariffs and export subsidies. For example, if the agreement is incomplete, at this stage, special interest groups might lobby for the values of the tariff and export subsidy ceilings.

Capital in the numeriare sector is generic,whereas capital in the manufacturing sectors is sector-specific. The adjustment cost of capital movements between the manufacturing sectors is sufficiently high, so capital always moves from and to the numeraire sector.

To investigate the rationale of asymmetric treatment between export subsidies and import tariffs, we assume that the production functions of the manufacturing goods are identical, and so, they are not a source of the asymmetry. Nonetheless, our results are independent of the endowments.

We can allow for a continuous decrease in transportation costs. The results are independent of the structure of the reduction in transportation costs.

The idea of this assumption is that firms anticipate exogenous technology improvements that save transportation costs over time.

We can easily allow for discounting. The parameter \(\theta \) can be chosen such that the equilibrium allocation without discounting under the chosen \(\theta \) and the equilibrium allocation with discounting are equivalent.

References

Bagwell, K., & Lee, S. H. (2018). Trade policy under monopolistic competition with heterogeneous firms and quasi-linear CES preferences (Working paper). https://kbagwell.people.stanford.edu/sites/g/files/sbiybj3371/f/tradepolicy_ces.pdf.

Bagwell, K., & Staiger, R. W. (1999). An economic theory of GATT. American Economic Review, 89(1), 215–248.

Bagwell, K., & Staiger, R. W. (2001). Strategic trade, competitive industries and agricultural trade disputes. Economics and Politics, 13(2), 113–128.

Beshkar, M., & Lashkaripour, A. (2017). Interdependence of trade policies in general equilibrium (Working paper).

Brander, J. A., & Spencer, J. B. (1985). Export subsidies and international market share rivalry. Journal of International Economics, 18(2), 83–100.

DeRemer, D. R. (2013). The evolution of international subsidy rules (ECARES working paper 2013–2145).

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1994). Protection for sale. American Economic Review, 84, 833–850.

Grossman, G., & Helpman, E. (1995). Trade wars and trade talks. Journal of Political Economy, 103(4), 675–708.

Itoh, M., & Kiyono, K. (1987). Welfare-enhancing export subsidies. Journal of Political Economy, 95(1), 115–137.

Johnson, H. (1954). Optimum tariffs and retaliation. Review of Economic Studies, 21(2), 142–153.

Levy, I. R. (1999). Lobbying and international cooperation in tariff setting. Journal of International Economics, 47, 345–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(98)00012-9.

Maggi, G., & Rodriguez-Clare, A. (1998). The value of trade agreements in the presence of political pressures. Journal of Political Economy, 106(3), 574–601.

Maggi, G., & Rodriguez-Clare, A. (2005). Import tariffs, export subsidies and the theory of trade agreements. Princeton University.

Maggi, G., & Rodriguez-Clare, A. (2007). A political-economy theory of trade agreements. American Economic Review, 97(4), 1374–1406.

Mitra, D. (2002). Endogenous political organization and the value of trade agreements. Journal of International Economics, 57(2), 473–485.

Staiger, R. W., & Tabellini, G. (1987). Discretionary trade policy and excessive protection. American Economic Review, 77(5), 823–837.

Suwanprasert, W. (2017). A note on “Jobs, Jobs, Jobs: A ”New” perspective on protectionism” of Costinot (2009). Economics Letters, 157, 163–166.

Suwanprasert, W. (2018). Optimal trade policy in a ricardian model with labor-market search-and-matching frictions (Working paper). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4014524

Suwanprasert, W. (2020). Optimal trade policy, equilibrium unemployment, and labor market inefficiency. Review of International Economics, 28(5), 1232–1268.

Tomell, A. (1991). Time inconsistency of protectionist programs. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(3), 963–974.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper was previously circulated under the title “Import Tariffs and Export Subsidies in the WTO: A Small-Country Approach” and “Why Does the WTO Prohibit Export Subsidies but not Import Tariffs?” We are grateful to Robert Staiger, Yeon-Cho Che, John Kennan, Bijit Bora, James Lake, and Kiriya Kulkolkarn for their invaluable comments. We thank editors Emily J. Blanchard and Gerald Willmann, as well as two anonymous referees, for their helpful suggestions. We have benefited from discussions with seminar participants at the Midwest International Trade conference (Fall 2017), Kentucky Economic Association conference (2017), Eastern Economics Association conference (2018), Southern Economics Association conference (2018), American Economics Association conference (2019), and World Trade Organization (WTO). Tanapong Potipiti thanks the WTO for its financial support. All remaining errors are our own.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Proof of Lemma 1

Proof

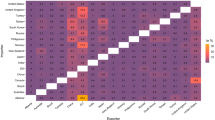

According to the equations in Proposition 1 and Proposition 2, the government prohibits only export subsidies but not import tariffs if \(\sigma \left( 1-\theta +\epsilon \right) \left( \frac{1}{2}+\frac{\theta ^{2}}{\theta -\epsilon }\right) >\left( \frac{1-\sigma }{2}\right) ^{2}\left( 1-\theta \right) ^{2}\) and \(\sigma \left( 1-\theta -\epsilon \right) \left( \frac{1}{2}+\frac{\theta ^{2}}{\theta +\epsilon }\right) <\left( \frac{1-\sigma }{2}\right) ^{2}\left( 1-\theta \right) ^{2}\). The two conditions can be satisfied simultaneously if \(\epsilon >0\). \(\square \)

1.2 Proof of Proposition 4

Proof

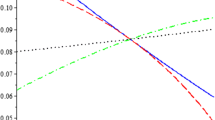

The functions \(\Omega _{X}\left( \lambda \right) \) and \(\Omega _{Y}\left( \lambda \right) \) in Eqs. (40) and (46) are continuously differentiable with the property that under the same set of parameter values, \(\text {d}\Omega _{X}\left( \lambda \right) /\text {d}\lambda >\text {d}\Omega _{Y}\left( \lambda \right) /\text {d}\lambda \) for all \(\lambda \). Therefore, the maximizers \(\lambda ^{\tau *}\) and \(\lambda ^{s*}\) must be such that \(\lambda ^{\tau *}\ge \lambda ^{s*}\). \(\square \)

About this article

Cite this article

Potipiti, T., Suwanprasert, W. Why does the WTO treat export subsidies and import tariffs differently?. Rev World Econ 158, 1137–1172 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-022-00457-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-022-00457-2