Abstract

The paper proposes a set of metrics and a methodology to measure the progress that European Union Member States are making towards the development and integration of capital markets. It identifies a set of indicators and analyzes the performance of these countries over the 2007–2018 period using a composite indicator approach (in both a static and dynamic environment), based on the six priorities related to achieving a well-functioning and integrated European capital market included in the European Commission Capital Markets Union Action Plan. The author uses robust clustering to identify groups of countries and tracks their development over time. He finds that the process of capital market development and integration process has started but is not completed and that it is mainly associated with countries’ adherence to European increasing trends driven by the benchmarks rather than the policy actions of countries aimed at catching up with the best performers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

European capital markets have experienced a continuous push towards development and integration in the last decades (Baele et al., 2004). Since the Treaty of Maastricht, the free movement of capital has been the backbone of EU’s single-market mission, aimed at allowing European citizens to complete financial operations (e.g., in terms of investments, banking transactions, shares acquisitions) and companies to invest and raise cheaper capital uniformly across the European Union. A further relevant milestone was the introduction of the euro, which boosted capital market integration in the European Monetary Union until the 2007–2008 financial crisis, when this trend reverted to negative (ECB, 2018). Indeed, the financial crisis and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis (2010–2013) have constituted a restraining factor for the integration process in Europe, both on the banking market (Emter et al., 2019) and in terms of cross-border capital flows (Howarth & Quaglia, 2013). The 2015 Capital Markets Union (CMU) is considered the EU policy response to these negative trends (Quaglia et al., 2016).

Specifically, CMU policies were designed to enhance capital markets under several tangential perspectives. First, capital market integration is thought to be prodromal to risk reduction in the overall system. Indeed, more integrated capital markets would enable easier economic risk-sharing among countries (Agenor, 2001; Bekaert et al., 2006; Veron & Wolff, 2016). Second, the ability of companies (and SMEs in particular) to improve their access to finance also depends on capital market development (Bekaert et al., 2005). In particular, more developed markets would extend the financing portfolio from banking loans to capital market instruments (Veron & Wolff, 2016) and fintech opportunities (Demertzis et al., 2018). Moreover, increasing capital in the equity markets would make their access cheaper, further stimulating investments (Dye et al., 2017; Kose et al., 2006). Third, within an integrated context it becomes easier for savers to better exploit investment opportunities, both to look for superior returns and to diversify their investment portfolio (Agenor, 2001; Boldeanu & Tache, 2016). These factors are also corroborated by the promotion of long-term and sustainable investments and by the development of a more structured alternative finance market (e.g., for venture capital/private equity), which is still limited in Europe with respect to the United States (AFME, 2018). Overall, in the case of the CMU all these areas would concur to provide beneficial economic effects, with the development of a stronger connection between individual savings and economic growth through the means of investments (European Commission, 2015).

Given the relevance of capital market (CM) development and integration in the EU political agenda, this work is aimed at investigating this process across the 28 EU countriesFootnote 1 from 2007 to 2018. We leverage the CMU Action Plan policy frameworkFootnote 2 and key objectives proposed by the European Commission (2015) to develop a set of metrics based on different quantitative approaches. Despite our research being mostly linked to existing literature measuring financial integration,Footnote 3 this work aims to introduce two main novelties.

First, we do not focus our analysis on the standard definition of financial integration but, rather, investigate the broader concept of capital market integration and development as emerging from the definition of the European policymaker. Specifically, we deviate from the most common definition of financial integration—based on the idea that an economic area is integrated if all countries have the same opportunities to access the market (Baele et al., 2004; Lemmen & Eijffinger, 1996)—and we adopt a measure of the development and integration of capital markets more closely related to the approach devised by the policymaker. This approach enables the development of an EU-specific monitoring tool, which could nevertheless be also applied to other geo-political contexts after adapting the underlying policy framework. Second, we conduct a robust statistical analysis adopting a set of different metrics specifically aimed at measuring multi-faceted concepts like capital market development and integration.

More specifically, we first use composite indicators: synthetic measures summarizing different relevant and related dimensions into a single comprehensive number (Nardo et al., 2008). The goal of this approach is twofold: on the one hand, to define and provide a simple-to-interpret tool to measure CM development and integration, and on the other hand, to observe the evolution of this indicator for the whole EU-28 and each individual country from 2007 to 2018, both through static comparisons of ranks emerging from composite indicators and through dynamic performance assessments based on data envelopment analysis (DEA; Coelli et al., 2005) and the Malmquist Index (Färe et al., 1994a, 1994b). This latter approach also allows us to disentangle the dynamic performance into country-specific versus more global European Union “environmental” drivers. Then, we cluster countries along different CM-related dimensions, adopting a statistically robust technique, i.e., a robust trimmed clustering model (García-Escudero, Gordaliza, et al., 2008). This analysis helps us capture country-level patterns across clusters in time that could be associated with a change in the progress of the development and integration of their capital markets.

Our results indicate that most European Union countries saw their capital markets develop and improve during the last decade, despite the process of convergence to the highest levels of the EU benchmarks being still ongoing. This result seems to suggest that EU common policies towards market integration provide beneficial effects for member states, in line with similar findings by Cherchye et al. (2007) for a broader set of internal markets and by the ECB (2018) for financial markets. Hence, we complement the existing literature by specifically analyzing capital markets, in light of the relevance and policy momentum emerging from the implementation of the Capital Markets Union Action Plan.

At the same time, by decomposing the dynamic development of EU capital markets via the Malmquist Index based on Färe et al. (1994b), we find that most of the beneficial effect is not guided by relative shifts towards the European benchmarks but, rather, by changes in the benchmarks for performance themselves. This result, consistent with Cherchye et al.’s (2007) interpretation, communicates that the European Union framework, and more recently the CMU policy, are creating a suitable environment conducive to global performance improvement, which most member states are exploiting to various extents.

Our work also contributes to the literature on the relationship between market integration and financial crises, as well as related policy responses in integrated markets such as the European Union (Emter et al., 2019; Howarth & Quaglia, 2013). Our results on capital markets go in the same direction as what has already been found in the literature on cross-border banking (Emter et al., 2019) and highlight a reduction in the integration of capital markets in Europe during the period of the sovereign debt crisis, i.e., between 2010 and 2013. At the same time, after the introduction of the CMU Action Plan the level of capital market development and integration once again settled on the values prior to the crisis. This reaffirms the importance of a single capital market in the EU as a resilient asset to respond to crises, similarly to what has already been experienced for the banking union (Howarth & Quaglia, 2013).

At the same time, we find that this more recent leap forward in the integration and development of EU capital markets (contemporary to the launch of the CMU Action Plan) seems to be equally driven by both the catching up of countries lagging behind during the crisis and the further improvement of the top performers, thus suggesting that (additional) policy initiatives at the EU level are becoming increasingly relevant to consolidate an environment that can further boost capital market development and integration.

Lastly, our findings show also relevant policy implications on economic growth. Indeed, we find that our CMU indicator is positively correlated to standard global capital market openness measures, i.e. the Financial Openness Index (Chinn & Ito, 2006) and the Capital Control Indicator (Fernández et al., 2016). Hence, our results seem to confirm the CMU Action Plan as a concrete and relevant driver for European mid-term growth, given the positive relationship between financial and capital market openness and economic growth (see, for instance, Bussière & Fratzscher, 2008).

The remainder of this work is organized as follows. Section 2 includes a description of the theoretical policy-based framework constituting the rationale for the monitoring of the progression of CM integration and of the selection of the associated indicators, as well as a discussion of the performance of EU countries based on a composite indicator approach. In Sect. 3, we move to the dynamic assessment of country performance based on data envelopment analysis and a robust clustering approach. Moreover, leveraging a Malmquist Index analysis we investigate whether these dynamics are driven by an individual country’s ability to catch up to Europe’s top performers (those with the most developed capital markets) or by the benchmarks themselves improving. To corroborate our findings, we then investigate the correlation of our composite metrics with standard de jure capital market openness measures (in Sect. 4) and compare our findings to those obtained with similar metrics in the literature (in Sect. 5). Lastly, Sect. 6 offers some concluding remarks.

2 Measuring capital market development and integration

2.1 The policy framework

To measure the progress of EU countries in the development and integration of capital markets, we follow the framework established by the European Commission in its Capital Markets Union (CMU) Action Plan (European Commission, 2015). Specifically, the European Commission has identified six central objectives,Footnote 4 the pursuit of which are beneficial for the realization of a single EU capital market: 1. financing for innovation, start-ups, and non-listed companies; 2. making it easier for companies to raise funds on capital markets; 3. promoting investments in long-term, sustainable projects and infrastructure projects; 4. fostering retail and institutional investments; 5. leveraging bank capacity to support the economy; 6. facilitating cross-border investments and promoting financial stability.

The first two objectives seek to introduce financing sources other than bank credit for companies at all stages of life. This is particularly important for access to alternative financial instruments in the pre-IPO phase, while the latter objective aims to facilitate companies’ access to public markets and the capture of debt and/or equity instruments. The third objective reflects the need to channel capital towards infrastructure and sustainable investments so as to favor new employment and strengthen sustainable growth, respectively. Objective 4 calls for a greater opening of the market for (retail and institutional) investors to increase their savings by offering households the best options for their pension decisions. Objective 5 aims to strengthen the capacity of banks to continue supporting economies through financing. This is made possible by transferring risk from the original lender to investors, freeing up the banks' capital for new credit grantings. Finally, Objective 6 includes initiatives to create a fully integrated market with harmonized rules and without obstacles to the flow of capital, in order to increase the EU’s ability to compete globally.

In this work, we consider these objectives as basic “pillars”Footnote 5 with which to measure the progress of countries towards CM development and integration. The two main reasons are that we aim to limit arbitrariness in the framework definition by selecting a truly exogenous one that is defined by the policymaker; second, we want to introduce a monitoring instrument in line with the policy framework. However, there is still a certain degree of arbitrariness given that more than one indicator could actually be assigned to each objective.

2.2 The indicators

The selection of representative indicators underlying the theoretical framework results from a mixture of different criteria. First, we look for a good compromise between the fulfillment of the indicators with respect to their main objectives and the availability of data in our sample. Consequently, we initially tried to adopt indicators from European Commission documents (e.g., European Commission, 2016). We then analyzed previous works measuring the progress of capital markets in the EU in order to broaden the set of possible indicators (AFME, 2018; European Central Bank, 2018). As a second criteria, we select indicators with a yearly frequency (for the 2007–2018 period) and for all individual EU-28 countries, so as to avoid imputing missing data. Third, we give preference to data whose source is public and official, in order to facilitate replication of the analysis over time. However, these three criteria are subject to data availability restrictions. In particular, we confirm the lack of official statistics with the required granularity for indicators related mainly to Pillar 1 (for example, on venture capital and private equity) and 3 (for example, on alternative bonds). Therefore, for these cases we use data from private sources, based on the pragmatic idea that each objective should be characterized by at least one indicator.

The adoption of these criteria results in 11 indicators, two for each of the first 5 pillars and 1 for the last, which are available for the 2007–2018 period and for the 28 EU countries. The indicators used are designed in such a way that their (positive) growth is associated with a positive contribution to the improvement of capital markets. Pillar 1 is composed of two different indicators that describe the degree to which alternative financing instruments, namely venture capital and private equity, are being introduced. These indicators are expressed as the ratio between private equity or venture capital volumes and outstanding loans from non-financial corporations (NFCs). Therefore, an increase in this ratio would show the growing relevance of alternative instruments compared to traditional financing. Similarly, two indicators within Pillar 2 measure access to debt and equity markets: “relevance of NFC debt” and “relevance of NFC equity”. In these cases, the total outstanding debt or publicly traded shares of firms are compared to outstanding NFC loans. Also in this case, a growing ratio indicates greater access to capital markets for firms. Pillar 3 also consists of two different indicators. On the one hand, the “adoption of alternative instruments” is formed as the ratio between the number of green, social, and sustainable bondsFootnote 6 issued over the total number of bonds issued. An increase in this ratio means that the diffusion of alternative bonds is becoming more relevant in the relevant market. On the other hand, investments through public–private partnerships are used as an absolute value (expressed in billion euros). Pillar 4 is based on savings from both retail and institutional investors expressed as a fraction of gross domestic product. A rise in these indicators implies an increasing availability of saving funds. Pillar 5 consists of two indicators: first, the ratio between the issuance of covered bonds and the total amount of outstanding loans in the economy, which shows the ability of banks to transfer risk to the market, and second, “deposit-taker capital adequacy”, an indicator produced by the International Monetary Fund that describes the soundness of the financial system and measures regulatory Tier 1 capital to risk-weighted assets.Footnote 7 Finally, the sixth pillar measures how the share of foreign investment is changing. As an approximation, we consider home-bias, which is a measure of the overweighting of domestic investments in a country (Schoenmaker & Bosch, 2008). We take its complement to 100% to ensure it makes a positive contribution to the overall metrics. An increasing share of foreign investment means more interconnected equity and debt markets within the EU, which could lead to greater financial stability (Nardo et al., 2017).

Table 1 describes the selected indicators assigned to the six objectives and the average EU performance for each of them before and after the adoption of the CMU Action Plan in 2015.Footnote 8

In the last four years of the sample, the mean value increased for nine of the eleven indicators compared to the average for the 2007–2014 period. Conversely, a negative evolution was seen in Pillar 5 (with slightly decreasing covered bonds) and Pillar 3 (PPP more than halved). Furthermore, the performance among countries is quite heterogeneous, with some results contrary to the average. In particular, less than 50% of countries reported a decline in the indicator for cross-border portfolio debt and equity investments in 2015–2018. However, the performance of most member states in all indicators is in line with the mean in terms of sign.

2.3 The composite indicator approach

Despite generally increasing in time, countries’ performances in the pillars are at least partially contrasting, with a few indicators showing lower performances in the 2015–2018 period. This variability does not provide a clear picture of the overall phenomenon and needs to be synthesized by a single number. For this purpose, we adopt the composite indicator, as a tool that can better measure multidimensional phenomena (Floridi et al., 2011). In fact, this method allows pooling several indicators into a single number and comparing the aggregate performance of the observed individual units with each other and over time (Saisana & Tarantola, 2002). Therefore, it is a useful metric to examine the evolution of the relative performance and progress of individual countries in our sample in relation to CM development and integration.

However, the composite indicator literature suggests that the relative performance of countries is subject to the “arbitrary” approach used to construct the composite indicator itself (Valdes, 2018). In particular, each phase of the construction of the indicator (that is, the normalization of the raw data, the weighting of the normalized data, and their final aggregation) implicitly entails a source of arbitrariness and, consequently, variability of the final composite (Böhringer & Jochem, 2007; Ebert & Welsch, 2004).

In order to account for the level of arbitrariness, following Saisana and Munda (2008), Munda and Saisana (2011), and Floridi et al. (2011) we adopt a “non-simplistic” approach for composite indicator construction (Luzzati & Gucciardi, 2015). The intuition behind this methodology is to directly propose a “plausible” rank, rather than a single one based on a specific ad hoc combination of (normalization, weighting, and aggregation) techniques. Following this approach, we generate 32 different yearly rankings for the 2007–2018 period, emerging from the combination of five normalization, four weighting, and two aggregation techniques.Footnote 9 We produce 11 different “experiments”,Footnote 10 each keeping one technique fixed and changing the others. Hence, five experiments come from normalization, four from weighting, and two from aggregation. For each of these scenarios, we calculate the average rank by member state and year. The minimum and maximum values among these averages can vary between 1 and 28 (even if in practice some ranks are not filled due to the average in the experiments) and represent the delimiters of the range of possible ranks. Lastly, to determine the plausible rank, we take the average of the ranks of the 11 experiments, again by country and year.

We first provide a visual representation of the results for 2018, which are in line with the outputs produced by Saisana and Tarantola (2002), Saisana and Munda (2008), and Luzzati and Gucciardi (2015), among others. Specifically, Fig. 1 represents the ranking of the 28 EU countries according to our (plausible) composite indicator metrics.

The uncertainty around the construction of composite indicators and related rankings is embedded within this kind of representation. In particular, on the one hand countries are ordered using the plausible rank (indicated with a dark grey dotFootnote 11), based on the definition already provided. The emerging result provides the plausible ranking of EU countries for 2018 for our composite indicator metrics. Nevertheless, this is a peculiar ranking since it does not cover the entire possible distribution (from 1 to 28) but is instead capped at 3 and 25 and some inner ranks are never covered (for instance, 4, 12, and 16), since ranks are calculated as averages of different experiments. On the other hand, the light-grey bar represents the plausible range, which is delimited by a lower and an upper bound, respectively obtained as the minimum and the maximum value of the ranks obtained by the country according to the 11 experiments. The more extended is the bar, the larger is the maximum dispersion around the average of the country’s ranks.

What emerges from this analysis is that despite this ranking embedding the uncertainty inherent the construction of composite indicators through ranges of rankings, an individual country’s ranking domain is still limited to a few positions. In other words, our approach allows discriminating country performance, for instance, determining if, on average, one country exhibits a relatively better performance than another. For example, Denmark (the top-placed) shows a clearly better performance than Latvia (the last one), but also compared to France and the Netherlands (the 6th and the 7th), despite some uncertainty still remaining for closer ranks. All in all, we can rely on our plausible ranking approach as a tool for comparing performance between countries.

Based on this method, we can also provide a first descriptive grouping of member states based on their 2007–2014 ranking and their growth performance in the period from 2015 to 2018, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

The taxonomy used to define the quadrants in this figure is adapted from Fagerberg and Srholec (2005)

CMs performance matrix (2015–2018 vs. 2007–2014) by EU country.

In this figure, the overall region is divided into four quadrants by two axes. The first separates member states along the vertical axis into those with a promising standing (first half of the ranking) and those with potential for improvement (second half). The second groups countries along the horizontal axis into those rising (right side) and declining (left side) in their relative rank. To prevent a strict interpretation of the data, we additionally include a “buffer” area between –5 and + 5 percent in which the performance of member states may be regarded as constant over time.

Four clusters appear from this depiction. First, the “moving ahead” group in the upper-right quadrant reflects top-level performance consolidation, with more than 5% gains from 2007–2014 to 2015–2018. On the opposite side of the matrix, three “falling behind” states are losing ground in their rankings and were already in the bottom half of the 2007–2014 standings. Two countries are “losing momentum”, meaning they maintain a strong position but have a large relative decrease in ranking compared to the previous period. Four member states, on the other hand, are “catching up”, having gained a considerable boost in ranking that shows them converging toward more solid performances. All other member states exhibit steady performances when comparing the periods before and after the CMU Action Plan.

This descriptive approach acknowledges different levels of development and integration of capital markets within the EU and provides suggestive indications that the EU process of convergence in this field has not been accomplished and is still ongoing. Nevertheless, we find an overall average improvement since 2015. This insight is not surprising given that, on the one hand, the Action Plan is a progressive program with actions to be implemented from 2015 to 2019 and, on the other hand, many of the dimensions underlying the composite indicator require a congruent time to favorably react to the enacted policies.

2.4 Decomposing capital markets metrics by CMU key objectives

While one of the primary benefits of composite indicators is that they provide a synthesis of heterogeneous phenomena, decomposing the final scores into their components may be beneficial in understanding the function that each underlying indicator or objective plays in determining the final ranking. With this in mind, we analyze the variation in the pillars from the broader capital market metrics, constructing a country ranking for each of the six components and comparing it to the plausible ranking derived from the overall composite indicator. In other words, we evaluate member states based on the six objectives underpinning the CMU Action Plan to determine whether the resulting rankings are (on average) more or less aligned with the plausible ranking derived from the overall CMs metrics and which pillars compensate for each other.Footnote 12

For this analysis, we choose 2018 as the reference year. Interestingly, the 2018 rankings based on individual pillars do not provide the same member state positions as the plausible ranking (shown in Fig. 1). Comparing rankings reveals that pillar 4 (foster retail and institutional investments) has the most consistent behavior with the plausible ranking of one. On the other hand, the pillars showing more variability are the fifth and sixth. This variation reveals that states listed in the top half of the plausible ranking are penalized when only pillars 5 (leverage bank capacity to support the economy) and 6 (facilitate cross-border investment and promote financial stability) are included. This finding is policy-relevant since it might indicate countries’ vulnerable areas, which can be the focus of measures to further promote CM development and integration. Looking at the objectives with the greatest difference as compared to the plausible ranking (i.e., 5 and 6), some of the member states with the most important gaps are not in the Eurozone, which according to our assessment may function as a facilitator for cross-border investment in the absence of currency risks.

Overall, these data yield two major conclusions. First, while there is evidence that fostering retail and institutional investments (i.e., objective 4) appears to be the best single proxy for investigating CMs performance at a glance, the definition of a metric measuring capital market development and integration is inherently multi-faceted and cannot be fully synthesized by a single pillar without losing relevant information supplied by the others. Second, based on evidence that member state performance is not uniform across pillars and that some of them (i.e., 5 and 6) exhibit more relevant changes in rankings, policymakers could set different priorities for each objective to foster CM development and integration according to a more focused and efficient approach.

3 Dynamic performance assessment

Up to this point, we have examined member state performance in terms of their relative position in annual rankings from 2007 to 2018. Despite the ability to compare countries across time, this type of investigation is inherently static because rankings are created on an annual basis and any improvement (worsening) in a country’s rank can only offer information about its relative position. In this section, we adopt a collection of tools that can shed the light on two further relevant perspectives: whether the country is improving its performance in comparison to a common benchmark, and whether the overall performance of the EU-28 is rising (lowering) over time. To examine the evolution of member state performance over time in this way, we use two complementary methodologies: data envelopment analysis (Charnes et al., 1978; Farrel, 1957) and the Malmquist Index (Caves et al., 1982; Färe et al., 1994a, 1994b; Malmquist, 1953). Furthermore, for the sake of robustness we compare the DEA findings to those obtained from a robust cluster analysis.

3.1 Data envelopment analysis

The original aim of data envelopment analysis (DEA) is the evaluation of the efficiency of productive “decision-making units”, based on inputs and outputs, in a non-parametric setting in which the functional form of the production function is not known a priori. The objective is to identify the most limited set of viable inputs for each examined unit in order to determine the greatest potential output (Coelli et al., 2005). As a result, units can be rated depending on their proximity to the efficiency frontier: If their efficiency cannot be improved given their inputs, units are on the frontier and receive the highest possible score (that is, 1), whereas if it can be improved using a feasible different combination of inputs, their score is represented as a fraction of 1, based on the distance from the frontier itself (Charnes et al., 1978).

Interestingly, this technique has also impacted the literature on composite indicators, for two primary reasons. First, DEA provides a ranking of units based on some input and output variables, just like composite indicators provide a score (and hence a ranking) based on the aggregation of sub-indicators. Second, DEA enables this ranking to be obtained without establishing a hard functional form in the indicator’s construction.Footnote 13

As a result, and in line with Cherchye et al. (2007), in our framework units correspond to the 28 EU member states, inputs are created as an equal-to-one dummy variable, and outputs are the 11 indicatorsFootnote 14 underpinning the CMs metric. Furthermore, the reference periods are the years from 2007 to 2018.Footnote 15 We first present the 2018 results, which are depicted in Fig. 3.

In 2018, nearly 40% of member states reached the CMs metrics frontier (in blue in Fig. 3), decreasing from 46% in 2017 but still a higher value than the average for the whole sample period (37%). Remarkably, while four countries moved away from the frontier between 2017 and 2018, two of them reached it over the same time period. At the same time, more than half of the member states that were below the frontier in 2017 managed to improve their relative performance, moving closer to or reaching it in 2018. Furthermore, in 2017 and 2018 the average distance to the frontier, computed as the arithmetic mean of the distance to the frontier by country, remained relatively steady (87%).

We also replicated the analysis comparing the average post-CMU Action Plan performance to that before the implementation of the CMU Action Plan. Specifically, we compute the average number of members states on the frontier in the 2007–2014 period versus 2015–2018, as shown in Table 2.

Two major outcomes emerge. First, since 2015 the proportion of countries moving to the frontier has risen, on average. Indeed, during the post-CMU Action Plan period almost 40% of member states received a score of 1, compared to only 36% from 2007 to 2014. This outcome serves as a further signal of the convergence of EU member states towards the development and integration of capital markets. Moreover, this approach provides some insights that help link the consequences of the European Sovereign Debt Crisis to the evolution of EU capital markets. Indeed, the share of member states on the frontier reached an average of approximately 34% in the 2010–2013 period, decreasing from 38% in the previous period (2007–2009) but increasing again since 2014 and stabilizing, as previously stated, roughly at the pre-crisis level in the post-CMU phase. This is also consistent with Emter et al. (2019), who find a link between deteriorating financial assets due to the crisis and the reduction of financial market integration displayed by the retrenchment of EU cross-border banking.

Overall, these findings reflect the outcomes of the composite indicator analysis: a rising performance since 2015, with a light slowing in the final years of the sample. Indeed, while on average the European Union experienced an essentially steady performance in terms of capital market development and integration progress from 2017 to 2018, a drop in the number of member states on the frontier (from 13 to 11) emerged over the same period.

3.2 Robust cluster analysis

Following Cariboni et al. (2015), we conduct a robust cluster analysis to provide more evidence for previous conclusions, with the goal of further studying the dynamic trajectories of member states toward EU capital market development and integration. With this in mind, we use the robust trimmed clustering model established by Garcia-Escudero et al. (García-Escudero, Gordaliza Ramos, et al., 2008; García-Escudero, Gordaliza, et al., 2008), due to its applicability and suitability to our investigation approach.

This technique allows us to take advantage of three important features. First, the suggested number of clusters does not need to be chosen a priori since the most appropriate number arises from a statistical criterion (e.g., the Bayesian information criterion, BIC), which allows the selection of the most informative model, thereby minimizing ex ante assumptions (Fraley & Raftery, 1998). Second, unlike standard techniques such as k-means, this methodology allows for more flexible clustering as well as “non-spherical” shapes (Garcia-Escudero et al., García-Escudero, Gordaliza, et al., 2008). Third, this approach retrieves a number of outliers from the data, which may be removed from the overall clustering estimation to prevent biases (Rocke & Woodruff, 1996).

Our clustering is based on the same eleven variables that underpin the formulation of our CMs (composite indicator) metrics. We adopt the MATLAB function tclust to estimate the clusters using robust approaches (Riani et al., 2012). However, given the number of investigated countries, this approach is not able to handle the estimate of more than two clusters;Footnote 16 therefore, we first run a principal component analysis (PCA) to obtain a reduced number of components to include in the clusterization, yielding four components.Footnote 17 Even though these four components are not always dominated by a single variable, a predominance for each of them may be established. Specifically, based on factor loadings analysisFootnote 18 we get that the first component is guided by two pillar 4 indicators (retail and institutional investments) and one pillar 2 indicator (relevance of NFC equity). The second is driven by cross-border portfolio debt and equity investments and deposit-taker capital adequacy, the third by the covered bonds indicator, and the fourth by the use of alternative instruments.

The robust trimmed clustering methodology depends on the specification of three parameters to estimate our clusters: the supposed number of clusters (k), the proportion of outliers to be discarded (α), and the restriction factor on the covariance matrix shape (RF). Given the size of the sample (28 member states), we test two potential values for k (2 and 3) and three for α (3.6, 7.1, and 10.7 percent, respectively accounting for the exclusion of one, two, or three countries from the sample). Furthermore, we investigate six alternative degrees of restriction factors, namely 1 [equivalent to the conventional k-means clustering technique (Hartigan & Wong, 1979)], 5, 50, 100, 200, and 500. As a result, we estimate 36 alternative cluster analyses based on the three selected parameters. The optimal specification is then chosen based on the monitoring of the BIC. The estimate is done year by year for the duration of the analysis (2007–2018). This allows us to assess the consistency of the optimal specifications over time and the performance of countries’ CMs metrics through a dynamic analysis of their membership in the same or other clusters.

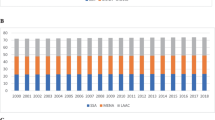

Coming to the results shown in Fig. 4, our robust clustering trimmed estimation leads to the selection of a model with three outlier countries and two clusters for each year of the sample.Footnote 19

The first implication of the trimming is the exclusion from clustering of member states with consistently high performance (signaled with grey in Fig. 4). Among the outliers, we get several countries that perform extremely well in one or more components when compared to the average. This is certainly the case of the United Kingdom, which outperforms in many areas, and Denmark, which is significantly strong in the covered bonds indicator, the Danish covered bond market being one of the oldest and most advanced in Europe (Dick-Nielsen et al., 2012), as well as Sweden and Luxembourg. Nevertheless, outstanding performances are not necessarily equally distributed across all pillars, with some outlying countries showing less robust performances in specific areas (e.g., cross-border investments and financial stability in the case of the UK). Moreover, we do not consider a few additional member states exhibiting an outlying performance in only a few years of the sample as strict outliers.

Regarding the characterization of the two clusters, we divide them into “standard performers” and “top performers” (shown in Fig. 4 with green and blue, respectively), where the latter is defined as the group of countries performing better for the majority of the components underlying the cluster estimation.Footnote 20 We should emphasize that the components that determine the definition of the “top performer” group are not homogeneous and stable over time and are dependent on the yearly clustering estimation. For instance, member states allocated to the “top performer” cluster in 2007 exhibit quite good or very good performances in components 1, 2, and 4 (though only fair performance in component 3) but countries assigned to the same cluster in 2018 show top performance in components 1 and 4. However, other factors are more commonly correlated with high performance. Indeed, in eleven of the twelve sample years components 1 and 4 are essential in establishing the criteria for the “top performer” cluster. Together with pillars 2 and 3, which are partially covered by components 1 and 4, these two components make up all of the contents of pillar 4 (foster retail and institutional investments) and appear to be primarily linked with a strong overall performance in CM enhancement. Conversely, a good performance in components 2 and 3, which sum up all the contents of pillars 5 (leverage bank capacity to support the economy) and 6 (facilitate cross-border investment and promote financial stability), is associated with membership in the “top performer” cluster only in 25% and 50% of cases, respectively, confirming the insight regarding the limited correlation of pillars 5 and 6 with the overall CMs metrics (see paragraph 2.4).

Looking at individual performance, several countries exhibit very consistent trends across the whole period. Specifically, four member states are always clustered among the “standard performers” (Greece, Croatia, Hungary, and Romania), while another ten are mostly part of this group, as they are classified as such for at least 80 percent of the period (Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Germany, Ireland, Estonia, Latvia, Poland, Portugal, and Slovakia). On the other hand, in addition to Denmark, Luxembourg, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, three countries stand out as “top performers”: the Netherlands (for eight years) and Italy and France (for six years). The remaining seven member states show occasional variation in their patterns, with some of them belonging to the “top performer” cluster in the first (e.g., Belgium, Malta, and Slovenia) or last years of the sample (e.g., Finland, France, and Spain).

Investigating the aggregate pattern of countries over time, we can see that the ratio of member states moving towards higher performance has been growing since 2015. Indeed, as indicated in Fig. 4 about 28% of countries, on average, belong to the “top performer” cluster in the post-CMU Action Plan period, whereas the ratio for the 2007–2014 period was just 18%, accounting for a 9-pp difference between the two phases. Furthermore, if we isolate the European Debt Crisis period (2010–2013) we see that the proportion of member states belonging to the “top performer” cluster is lower (10%) than in the post-CMU Action Plan phase and declined compared to the prior period (2007–2009).

Hence, these findings overall support the conclusions of the DEA, providing solid evidence on average increasing levels of CM development and integration, particularly after the drop due to the European Sovereign Debt Crisis and since the launch of the CMU Action Plan.

3.3 Measuring the evolution across time through the Malmquist Index

So far, we have observed that an increasing performance in terms of capital market integration and development has been materializing in recent years. The next step is to determine whether this growth is mostly due to increases in the “relative” performance of countries against European market benchmarks, to benchmarks themselves improving over time, or to a balanced combination of these two outcomes. To address this question, we use the methodological approach developed by Caves et al. (1982), who proposed the adoption of DEA within a dynamic context.

The underlying idea in Caves et al.’s work is to expand the DEA method by measuring the development of unit performance across two periods through the estimation of the ratio of the distance between each point and a shared benchmark. Indeed, the possibility of using DEA to compare unit performance over time is restricted by the fact that individual ranks are intrinsically referenced to distinct frontiers that change over time. In contrast, the Malmquist Productivity Index (MPI) compares the change in performance between two observations from year to year by determining the ratio of the distances of these observations from the common frontier. In other words, the MPI traces the change (from period t to period t + 1) in each country’s performance relative to the frontier during the same time period (at period t or t + 1).Footnote 21 As a result, within this context it is feasible to compare both the performance of a country over time as well as against other countries (Bosetti et al., 2007).Footnote 22

Another interesting feature of the MPI is the possibility of decomposing the index into two factors (or effects), usually called “efficiency” and “technical” effects (Wang, 2015), whose product is by construction equal to the MPI. While these two definitions and their interpretation directly come from the productivity literature, they are adaptable to our setting. Intuitively, a country can reach the frontier (i.e., the benchmark performance) through two (combinable) effects. First, it can simply improve its own performance (efficiency effect). Second, it may come nearer to the frontier because the frontier itself moves (technical effect). In our setting, the efficiency effect would therefore measure the “idiosyncratic” capital market development and integration progress of each country, once the overall trend of the market (technical effect) has been taken into account.

More formally, the first factor can be defined as the ratio of the relative CM performance at time t and t + 1 with respect to the frontier in the same period. In our case, it can be interpreted as the share of the evolution of the capital market metrics inherently due to the individual country’s behavior (we call this the “idiosyncratic” effect). In other terms, this effect describes countries’ dynamic behavior within a DEA-like setting: An increase in this factor (i.e., a > 1 ratio) represents a convergence towards the frontier, while a decrease (i.e., a < 1 ratio) indicates a divergence from it. On the other hand, the second factor is defined as the geometric mean of two ratios: 1. the distance between a country’s performance at time t and the frontier taken first at time t and then t + 1; 2. the distance between a country’s performance at time t + 1 and the frontier taken first at time t and then t + 1. In our setting, we can think of it as the share of capital market development and integration evolution due to the global common best-practice trends (we call this the “adherence to global trends” effect). In practice, an increase in this factor (i.e., a > 1 ratio) signals that the movement of the frontier from t to t + 1 is favorable for the country, determining an improvement in the CM metrics.

As a result, we compute the MPI for the CM metrics (MCMs) for our sample, which includes the 28 EU member states as units of investigation from 2007 to 2018. We specifically look at the progression of CM Malmquist performance, comparing post- and pre-CMU Action Plan outcomes. To do this, we calculate the annual index by country and then take the geometric average of those results for the years 2007–2014 and 2015–2018, respectively. Lastly, we compute the geometric average of these outcomes by member state to produce the average EU-28 performance for the two periods, which is displayed in Table 3 alongside the factor decomposition.

Since 2007, the 28 EU member states have seen an improving yearly performance (+ 4.4%) on average, based on this synthetic index. Furthermore, we find no significant variation in annual performance when comparing the pre- and post-CMU Action Plan periods (+ 4.3% vs. + 4.5%, respectively). Remarkably, the total effect for the entire sample appears to be driven by the “adherence to global trends” factor (+ 4.5%), implying that the improving performance of member states in CMs is based on improving EU best-practice trends and an openness to global markets rather than country-specific policy initiatives allowing them to catch up to those benchmarks. In other words, this result reveals the predominant positive impact of a more favorable policy environment on CM development and integration and confirms that this progress in not guided by performance shifts with respect to best-performer countries.

At the same time, the adherence to global trends seems to be crucial mostly in the pre-CMU period (+ 5.8%), given that it more than compensates for the declining level of the idiosyncratic component (–1.3%), consistent with our DEA results. Conversely, since 2015 the two factors have contributed equally to the average Malmquist CM Index rise, with both components exhibiting a 2.2% annual increase. This result may be motivated by the fact that the European Sovereign Debt crisis might have generated a move away from the best performers for some countries (with a negative average idiosyncratic effect in the first period) and that the CMU policy mix, developed starting from 2015, managed to provide equal weight and relevance to both the catching-up factor in the following period (+ 2.2% average of the same effect in the 2015–2018 period), as well as the change in the benchmarks (though implicitly generating an overall reduction of this “genuine growth”).

We now turn to Fig. 5 to further explore the relationship between the decomposition of performance into the two factors and the overall evolution of the index, making use of geographical heterogeneity.

This graph combines two types of information. First, the color assigned to member states describes the 2007–2018 total MCM index. Countries in green substantially boosted their performance (> 5%), those in red considerably reduced it (–5%), and those in blue exhibited a steadier performance. Second, member states are distributed along two axes that reflect the “idiosyncratic” and “adherence to global trends” effects. Figure 5 shows that the “adherence to global trends” factor has a larger dispersion than the “idiosyncratic” one.

This finding has two interpretations. First, the EU’s global market openness appears to be more important than extra country-specific efforts to determine capital market enhancements. Indeed, we see that the eight member states with a substantial improvement in performance overall (in green in Fig. 5) have also seen an improvement in the “adherence to global trends” component (in seven cases greater than 5%). In other terms, global market openness appears to be more predictive of a country’s overall good progress in capital market development and integration than additional attempts to catch up to the EU benchmarks. Indeed, all member states that showed a considerable increase in the “adherence to global trends” component saw an increase in the overall index (and larger than 5% in 70% of cases). Second, a substantial increase in the “idiosyncratic” component does not appear to be the most effective predictor of an overall improvement in capital market integration (approximately 12% of the occurrences). In other words, according to our metrics once the global market trends have been taken into account, country-specific initiatives (potentially including actions implemented in accordance with the CMU) may not be sufficient to catch up in terms of capital market development and integration.

When focusing on the components of the changes in performance by country, we find that global change is systematically more important than idiosyncratic ones (in approximately 90% of cases). This result confirms that the overall development and integration of capital markets is mostly driven by a favorable policy environment within the EU. In order to provide further insight into this phenomenon, we compare the Netherlands and the UK, two countries at the frontier at the beginning and the end of the sample (i.e., whose idiosyncratic effect is equal to 100%) and for which we find the maximum and minimum level of environmental effect (+ 13% and – 5%, respectively). This difference means that the environmental effect has contributed more strongly for the Netherlands, which shows a more balanced performance across the different pillars in the spirit of the policy mix, compared to the UK, which was in turn penalized by its strong specialization in some pillars and very low performance in others, particularly with respect to CMU pillar 6 (cross-border investments and financial stability).

Two major conclusions arise from this analysis. On the one hand, the annual rise in the Malmquist CMs Index of EU member states is mostly explained by their involvement in global markets. When the global trend is considered, country-specific “idiosyncratic” catching-up initiatives do not appear to play a role in the development and integration of capital markets. On the other hand, while this finding is valid when looking at the 2007–2014 period, global patterns have explained just half of the overall growth since 2015, with benchmark catching-up shifts (mostly after the crisis) appearing as increasingly important to sustain the prior yearly growth pace.

Our findings are consistent with previous works analyzing the process of development and integration of the EU economies. In particular, leveraging a DEA composite indicator and a Malmquist analysis, Cherchye et al. (2007) find that the EU member states progress in different sectors, mostly thanks to the improvement of best practices rather than due to catching-up components, thus concluding that belonging to the EU environment is conducive to performance improvement for member states.

4 Comparing capital market development and integration metrics with de jure capital market openness measures

The Malmquist analysis suggests that the growth in our CM development and integration metrics is mostly guided by the adherence of countries to global trends towards open European capital markets.

To further corroborate these results, in this section we investigate the correlation between our capital market development and integration metrics and some popular measures of capital account and market openness. On one hand, we proxy capital market development and integration using both our composite indicatorFootnote 23 and the DEA scores. On the other hand, to account for global capital market openness trends we adopt a set of de jure openness measures, since they describe the presence of barriers to capital account transactions through an index according to which larger values are associated with lower restrictions to capital flows (Bussiere & Fratzscher, 2008).

All these measures are based on different interpretations and subsequent calculations of the IMF’s Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (AREAER), which provides as output a dummy variable codifying the restriction of international financial flows. Based on Cerdeiro and Komaromi (2019), in this work we consider and discuss the following measures.Footnote 24 The first is the Quinn Index (Quinn, 1992, 1997), which is constructed on capital and financial current account regulations, covering relevant aspects such as payments for imports, receipts from exports, payment for invisibles, receipts from invisibles, and capital flows by residents and by non-residents (Quinn et al., 2011). The second measure is the Chinn–Ito Financial Openness Index, also known in the literature with the acronym KAOPEN (Chinn & Ito, 2006). This index is obtained by taking the first standardized principal component of the AREAER dummies related to current account and capital account transactions, requirements on export proceed surrenders, and the existence of multiple exchange rates. For our purposes, we consider its normalized version with the [0, 1] range, where 1 indicates fewer restrictions on transactions. The third measure is the Capital Control Indicator, also known with the acronym FKRSU (Fernández et al., 2016). This index allows coding the presence of capital account restrictions for twelve different asset classes. Moreover, it provides a distinction between resident and non-resident transactions in the domestic and foreign markets. The fourth measure is the Wang–Jahan index (Jahan & Wang, 2017), which is more specifically built to assess lower-income countries and, for this reason, is less appropriate in this context than the original AREAER document. For the purposes of our correlation analysis, we adopt the Financial Openness Index (KAOPEN) indicator, mainly because the dataset is publicly available and because it covers most of our sample (27 countriesFootnote 25 from 2007 to 2017). For the sake of robustness, we also use the Capital Control Indicator (FKRSU), despite it covering only 23 countriesFootnote 26 for the same time span.

From a statistical point of view, we estimate the correlation between our metrics for capital markets development and integration and the de jure capital market openness measures performing both a rank-correlation analysis and an OLS estimation. Rank correlation is used to estimate the relationship between rankings of different variables. Here, we run eight different estimations based on the combination of comparisons between the composite indicator and the DEA with the ranking of the Financial Openness Index and the Capital Control Indicator, respectively, and using both the Spearman and Kendall rank correlation techniques.

Table 4 shows that a positive correlation emerges in all specifications, with coefficients of around 0.4 for all Spearman correlations. As expected, Kendall’s tau shows lower coefficients, but still around 0.3. All correlations are statistically significant, with the specifications including the Capital Control Indicator showing weaker p values. These results suggest that countries with higher-than-average levels of the capital market development and integration metrics also have a higher probability of reduced de jure barriers to capital flows and of being more open to global capital markets, thus confirming our previous findings.

We now estimate the same correlations with standard OLS. Following Fernández et al.’s (2016) methodology, we first take the average value over the common sample period (2007–2017) for each country and each variable (i.e., composite indicator, DEA, Financial Openness Index (KAOPEN), and Capital Control Indicator (FKRSU)). We then regress them according to the following specifications:

where \(C{I_i}\), \(DE{A_i}\), \(KAOPE{N_i},\) and \(FKRS{U_i}\) are the average values over the sample period of the scores of the composite indicator, DEA indicator, Financial Opennness Index, and Capital Control Indicator for country i, respectively, while \({\epsilon_i}\) is the error term. We are interested in determining the value of the \(\beta\) coefficient in each of the specifications, since it represents the correlation between the de jure measure of capital openness and our capital market development and integration metrics.

Table 5 shows the results of the OLS estimations. We find that the coefficients are positive and statistically significant in all cases, with higher significance levels for the specifications including our composite indicator as the dependent variable. Moreover, the correlation is slightly stronger when we use as regressor the Financial Openness Index rather than the Capital Control Indicator Index. Hence, overall, a positive correlation between our metrics and the de jure capital openness emerges, consistent with the ranking correlation analysis.

These results provide complementary evidence to the Malmquist factor decomposition analysis. Indeed, the choice to reduce (or eliminate) legal barriers to international capital transactions can represent a good approximation of countries’ implicit adhesion to the global capital markets trend of openness. Therefore, with this analysis we may argue that within our sample, a high level of development and integration of capital markets is positively correlated to high levels of adhesion to the global market, approximated by the de jure capital market openness. These findings also have important (policy) implications for economic growth. Indeed, given the positive relationship between financial and capital market openness and economic growth (see, for instance, Bussière & Fratzscher, 2008; Bumann et al., 2013; Langfield & Pagano, 2016; and Benczúr et al., 2018) and our CMU indicators being correlated to global capital market openness (rather than to country-specific measures), our results seem to confirm the CMU Action Plan as a concrete and relevant driver for European growth, at least in the medium to long term.

5 Comparing capital market development and integration metrics with similar measures in the literature

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt in the literature to use composite indicators and cluster analysis to track the development and integration of capital markets in the European Union. Other papers, however, have focused their research on using composite indicators to assess relatively comparable concepts, such as economic integration (König & Ohr, 2013), globalization (AT Kearney/Foreign Policy Globalization Index, 2002), and finance (Baele et al., 2004).

A more recent publication, comparable to ours, is the European Central Bank (ECB)’s periodic report (European Central Bank, 2018), which presents a composite indicator of financial integration in Europe. In particular, the ECB develops two metrics, a “price-based” one and a “quantity-based” one, aggregating data on cross-border holdings for different asset classes. Because we focus on volumes rather than prices, our composite indicator should be compared to the latter. Despite there being some variation in scope, granularity, and methodology between the ECB and our composite index,Footnote 27 some common patterns seem to emerge. Indeed, according to the ECB’s quantitative indicator, from the late 1990s to 2017 financial integration reached a peak between 2005 and 2008, declined until 2013, and lately rose again (2015–2017), albeit not returning to pre-crisis levels. This finding appears to be consistent with our DEA analysis, which was also supported by the robust clustering approach, and highlights improving performance in the post-CMU Action Plan era, but not entirely compensating for the drop shown in prior years during the crisis.

6 Concluding remarks

The objective of this paper was to provide a set of tools to measure the progress of EU-28 member states toward the development and integration of capital markets (CMs). To begin, we defined the scope of the analysis by selecting as a theoretical framework the 2015 European Commission Capital Markets Union (CMU) Action Plan, which is based on six key objectives to be pursued in order to enhance CM development and integration across Europe.

Because of the multidimensional nature of the CMU Action Plan, we identified the composite indicator as the best instrument for synthesizing multi-faceted phenomena into a (set of) scores and corresponding rankings. To limit arbitrariness, we created a collection of composite indicators arranged into “experiments” based on the alternative construction approaches that could be used. The average value of the experiments for each member state and year of the sample was then used to calculate a “plausible” ranking. We looked for changes in countries’ plausible ranks, and we found that the transition to higher levels of CM development and integration is still underway, with increasing average outcomes emerging after 2015.

To determine which of the rationales underpins the performance of countries, we compared their positions based on the six primary objectives of the CMU and the overall CMs indicator. It became clear that the performance of member states across the major objectives is not uniform and that some of them—in the areas of the soundness of banks and of cross-border investment facilitation—exhibit peculiarities when compared to the overall metric. This finding, which is also supported by the clustering analysis, enables the investigation of policy implications in the field of CM development and integration.

We next conducted a dynamic investigation using data envelopment analysis (DEA) and a Malmquist Index analysis to evaluate the development of member states’ performance in relation to annual benchmarks. Compared to the pre-Action Plan period, DEA revealed an increase in the average number of countries at the CMs metric frontier after 2015. Furthermore, this technique enabled the identification of member states with deteriorating performances during the European Sovereign Debt Crisis (2010–2013). We achieved similar results using robust clustering analysis, which revealed that the percentage of member states migrating to the “top-performer” cluster from the “standard” one has been growing in recent years, following a decrease during the European crisis. These findings are also consistent with those obtained and presented by the ECB (2018) through the construction of a financial integration composite indicator.

Finally, the Malmquist Index allowed us to examine the trajectory of countries’ performances from 2007 to 2018. In the whole sample, we found a rising performance in the yearly average of the Malmquist CMs metric for the 28 EU member states, with no significant variation between the post- and pre-CMU Action Plan periods. Furthermore, by considering the entire time span, we were able to account for the factors driving this evolution. Indeed, the growth was mostly guided by countries’ adherence to open global capital markets (particularly between 2007 and 2014) rather than by idiosyncratic factors, which appear to be more relevant since 2015. Finally, when looking at member states experiencing a considerable growth in the Malmquist CMs metric, it appears that global market openness, rather than country-specific policy initiatives, is decisive in predicting the CMs enhancement of EU countries. As a result, additional efforts to establish European and national policies in this area might be beneficial to improve the overall development and integration of CMs in Europe. This result is further reaffirmed by a set of rank-correlation and OLS estimations confirming the relationship between our metrics and some de jure measures of global capital market openness, which could be thought of as proxies of countries’ adhesion to global capital markets.

Overall, our findings indicate that the development and integration of capital markets in Europe has started, although the process of convergence to higher levels has not been completed and is still underway. This is not surprising given that the Action Plan was still in effect at the end of 2018 and that the dimensions underpinning our metrics might not respond quickly to the identified policies. Nonetheless, our measures appear to be primarily related to EU member states’ average adherence to the worldwide trend of increased openness of capital markets. At the same time, the adoption of (additional) policy initiatives is becoming increasingly relevant, if not necessary, in order to consolidate this long-term growth.

Notes

The United Kingdom is included as an EU member state within the analysed sample.

For reference, see the official regulation “European Commission, COM (2015) 468 final—Action Plan on Building a Capital Markets Union”.

In 2017, the European Commission published a mid-term review of the CMU Action Plan, introducing a new key objective of “strengthening supervision and deepening capital markets in the EU”. This pillar is not included in our framework, mainly because its introduction can only be evaluated for the last two years of the sample (2017–2018).

In the rest of this work, we use both terms interchangeably.

According to the definition adopted by “Dealogic”.

A limited number of missing values were imputed using various sources (i.e., the European Central Bank and the World Economic Forum) as references, as reported in the footnote to Table 6 of the Appendix.

The selected set of indicators can fully represent the progress of CM development and integration according to the framework of policymakers. Indeed, this work should in principle focus on the integration of capital markets only within the EU, as the framework is based on the original structure of the CMU Action Plan (European Commission, COM (2015) 468 final), which contains a series of specific measures dedicated to EU member states. This means that when it comes to international capital flows, all indicators should only refer to cross-border movements within the EU. This would be the case in particular for Pillar 6, which is directly related to cross-border investments, and partly also for Pillars 1 and 2, as EU countries generally have access to foreign equity and debt capital markets. In this work, we were able to distinguish between regional (EU) and global cross-border flows for Pillar 6, as the granularity of the underlying source (i.e., FinFlows) made this analysis possible. However, due to limitations in the chosen data sources, we were unable to do the same for the others.

Tables 7, 8, 9 and 10 in the Appendix report details on the different techniques, their combinations, and an example of composite indicator scores for the whole sample based on z-score normalization, equal weighting by indicator, and linear aggregation. The scores and rankings for all 31 other composite indicators are available upon request.

See Table 11 in the Appendix as reference for the adopted “experimental” set-up.

The associated label indicating the rank is rounded up to the unit for graphical clarity.

If the difference between one pillar’s rank and the plausible rank falls within the range [– 1; 1], we consider it to be negligible and we interpret the pillar’s performance as aligned with the overall one. In other words, if that pillar is used as a proxy it may be a “good guess” of the entire CMs indicator. If the discrepancy is greater (smaller) than one, we conclude that the examined pillar is over-(under-)estimating the total rank. As a result, if the number of “good guesses” for each pillar is limited, then we conclude that it provides greater variability in the CMs ranking definition. For the purpose of robustness, we have also used sum-of-square metrics to assess ranking discrepancies, finding similar results.

This is especially important in terms of the weighting system because DEA may apply weights to dimensions by design in order to provide the best possible results for the units given their dimensions. This feature, also known as the “benefit of doubt” (BoD) in the related literature (Melyn and Moesen, 1991), is especially important since it decreases the amount of arbitrariness in the indicator’s development.

To prevent bias in the DEA estimation due to the presence of zeros in some of our indicators, we use a transformation of the indicators based on Bowlin (1998), which adds an extremely low scalar (in our instance 1E-16) in the presence of zeros. The Malmquist Index analysis follows the same transformation.

The DEA indicator calculated for the whole sample is presented in Table 12 of the Appendix.

tclust starts by estimating k ellipsoids based on i + 1 observations (where i is the number of indicators) chosen at random for each group. In our case, therefore, since the dataset has 28 countries and 11 indicators:

for k = 2: (i + 1) * k = 12 * 2 = 24;

for k = 3: (i + 1) * k = 12 * 3 = 36;

hence, tclust would fail for any k > 2.

Table 13 in the Appendix shows the PCA analysis results. The number of components is determined using both Kaiser (1960) and Jolliffe (1973) criteria, since the number of components showing larger-than-one eigenvalues (also taking into account their confidence intervals, as shown in Fig. 6 of the Appendix) and explaining approximately 70% of total variance is equal to four.

Shown in Table 14 of the Appendix.

As displayed in Fig. 7 of the Appendix, the analysis of the BICs suggests a substantial stability of the features of the most informative models. Indeed, for the whole sample we should choose two clusters (k = 2) and three outliers (α = 10.7%). Trimming is therefore important for model definition. At the same time, the restriction factor should be higher than 100 and, in particular, equal to 500 for most years (2007–2008, 2010–2015, 2017–2018) and equal to 200 for 2009 and 2016, even though even in these cases the difference between the 100 and 500 versions is quite small. This indicates that an ellipsoidal shape, rather than the usual spherical k-means structure, is better suited to categorizing our data.

At least three of the four components extracted from the PCA and used for clustering. In the event of a tie (2 versus 2 components), we choose the cluster with the highest median value of component centroid locations as the “top performer”.

To reduce arbitrariness, it is generally computed towards both borders (t and t + 1) and the final MPI is derived as their geometric average.

Several works have used this technique since Färe et al. (1994a) and Färe et al. (1994b), mostly to investigate productivity changes over time. Its application to composite indicators has recently renewed and expanded interest in this useful tool, particularly in the social (Bernini et al., 2013; Carboni and Russo, 2015; Peiró-Palomino and Picazo-Tadeo, 2018) and environmental (Kortelainen, 2008; Wang, 2015; Wang, 2019; Wang et al., 2016) fields.

In particular, the one built through the z-score normalization and linear aggregation of the equally weighted indicators.

A detailed discussion of the differences among the indices goes beyond the scope of this work. For a deeper description, see Quinn et al. (2011).

The index is missing for Luxembourg.

The index is missing for Estonia, Croatia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, and Slovakia.

First, the underlying indicators are different, with the ECB using the share of cross-border lending among monetary financial institutions (MFIs), MFI and investment fund shares of cross-border holdings of debt securities, and MFI and investment fund cross-border holdings of equity. Second, our composite is built at the EU-28 level and by individual countries, consistent with the CMU policy, while the ECB provides its indicator for the Euro Area only, not allowing for comparisons of relative performance across countries. Third, the ECB adopts a single methodology to develop the indicator, while we adopt a robust approach that takes into account 32 different methodological combinations. Lastly, the ECB indicators are given in comparison to data as of the end of the first quarter of each year, whereas we utilize year-end statistics.

References

AFME (2018). Capital Markets Union. Measuring progress and planning for success. https://www.afme.eu/Portals/0/globalassets/downloads/publications/afme-cmu-kpi-report-4.pdf

Agénor, P. R. (2001). Benefits and costs of international financial integration: Theory and facts. The World Bank.

Baele, L., Ferrando, A., Hördahl, P., Krylova, E., & Monnet, C. (2004). Measuring European financial integration. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 20(4), 509–530.

Baltzer, M., Cappiello, L., De Santis, R. A., & Manganelli, S. (2008). Measuring financial integration in new EU member states. ECB Occasional Paper, (81).

Bekaert, G., Harvey, C. R., & Lundblad, C. (2005). Does financial liberalization spur growth? Journal of Financial Economics, 77(1), 3–55.

Bekaert, G., Harvey, C. R., & Lundblad, C. (2006). Growth volatility and financial liberalization. Journal of International Money and Finance, 25(3), 370–403.

Beliakov, G., Pradera, A., & Calvo, T. (2007). Aggregation functions: A guide for practitioners (Vol. 221). Springer.

Benczúr, P., Karagiannis, S., & Kvedaras, V. (2018). Finance and economic growth: Financing structure and non-linear impact. Journal of Macroeconomics, 62, 103048.

Bernini, C., Guizzardi, A., & Angelini, G. (2013). DEA-like model and common weights approach for the construction of a subjective community well-being indicator. Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 405–424.

Böhringer, C., & Jochem, P. E. (2007). Measuring the immeasurable—A survey of sustainability indices. Ecological Economics, 63(1), 1–8.

Boldeanu, F. T., & Tache, I. (2016). The financial system of the EU and the Capital Markets Union. European Research Studies, 19(1), 59.

Bosetti, V., Cassinelli, M., & Lanza, A. (2007). Benchmarking in tourism destinations; keeping in mind the sustainable paradigm. In Advances in modern tourism research (pp. 165–180). Physica-Verlag HD.

Bowlin, W. F. (1998). Measuring performance: An introduction to data envelopment analysis (DEA). The Journal of Cost Analysis, 15(2), 3–27.

Bullen, P. S. (2013). Handbook of means and their inequalities (Vol. 560). Berlin: Springer.

Bumann, S., Hermes, N., & Lensink, R. (2013). Financial liberalization and economic growth: A meta-analysis. Journal of International Money and Finance, 33, 255–281.

Bussiere, M., & Fratzscher, M. (2008). Financial openness and growth: Short-run gain, long-run pain? Review of International Economics, 16(1), 69–95.

Carboni, O. A., & Russu, P. (2015). Assessing regional wellbeing in Italy: An application of Malmquist–DEA and self-organizing map neural clustering. Social Indicators Research, 122(3), 677–700.

Cariboni, J., Pagano, A., Perrotta, D., & Torti, F. (2015). Robust clustering of EU banking data. Advances in statistical models for data analysis (pp. 17–25). Springer.

Caves, D. W., Christensen, L. R., & Diewert, W. E. (1982). The economic theory of index numbers and the measurement of input, output, and productivity. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 50, 1393–1414.

Cerdeiro, D. A., & Komaromi, A. (2019). Financial openness and capital inflows to emerging markets: In Search of robust evidence. International Monetary Fund.

Charnes, A., Cooper, W. W., & Rhodes, E. (1978). Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European Journal of Operational Research, 2(6), 429–444.

Cherchye, L., Lovell, C. K., Moesen, W., & Van Puyenbroeck, T. (2007). One market, one number? A composite indicator assessment of EU internal market dynamics. European Economic Review, 51(3), 749–779.

Chinn, M. D., & Ito, H. (2006). What matters for financial development? Capital controls, institutions, and interactions. Journal of Development Economics, 81(1), 163–192.

Coelli, T. J., Rao, D. S. P., O’Donnell, C. J., & Battese, G. E. (2005). An introduction to efficiency and productivity analysis. Springer.

Cournède, B. & Denk, O. (2015). Finance and economic growth in OECD and G20 countries (No. 1223). OECD Publishing.

Demertzis, M., Merler, S., & Wolff, G. B. (2018). Capital Markets Union and the fintech opportunity. Journal of Financial Regulation, 4(1), 157–165.

Dick-Nielsen, J., Gyntelberg, J., & Sangill, T. (2012). Liquidity in government versus covered bond markets (BIS Working Papers No. 392).

Dye, J., Gilbert, A., & Pacheco, G. (2017). Does integration lead to lower costs of equity? Australian Journal of Management, 42(1), 86–112.

Ebert, U., & Welsch, H. (2004). Meaningful environmental indices: A social choice approach. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 47(2), 270–283.

Emter, L., Schmitz, M., & Tirpák, M. (2019). Cross-border banking in the EU since the crisis: What is driving the great retrenchment? Review of World Economics, 155(2), 287–326.