Abstract

Two decades of research have established pronounced exporter productivity premia (EPP) and exporter size premia (ESP). Yet, we do not know why such exporter premia differ so widely in magnitude across countries or sectors? We take this question to the theory and to the data. We derive the sectoral EPP and ESP in a standard heterogeneous firms trade model and apply the insights from the model to guide our empirical investigation of detailed Danish firm-level data. We show that a significant share of the observed variation in EPP and ESP across sectors can be accounted for by sector differences in the underlying variation in productivity dispersion, variable trade costs, the ratio of fixed export costs to fixed costs of production, and the elasticity of demand.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use the term premia in line with previous literature referring to differences between firms that export and firms that do not.

On a different note, our work also highlights that certain policies (such as policies that reduce trade costs for firms) can impact on the size of the EPP and ESP.

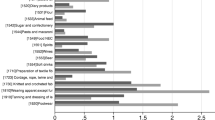

We obtain EPP and ESP estimates from industry-by-industry regressions of TFP respectively sales on an exporter status dummy conditioning on firm-specific and time-specific fixed effects (see Sect. 5).

Note, that negative exporter premia are not quite as exceptional as one would suspect, see Schröder and Sørensen (2012) for a theoretical underpinning and examples of empirical findings.

In contrast to both these papers, much of the remaining literature on country-level exporter premia are single-country studies (see the surveys of Greenaway and Kneller 2007; Wagner 2007, 2012; Bernard et al. 2012; Hayakawa et al. 2012). In particular, the implementation of different estimation strategies makes comparisons across studies difficult.

The application of the Pareto distribution within heterogeneous firms trade models is by now common. Moreover, the Pareto approximates the distribution of productivity of firms found in empirical work (see e.g. Luttmer 2007) and resembles the empirical patterns we find for Danish firms at least for the right tail of the distribution, see Fig. 1 and Sect. 3.1.

We assume that all first-order partial derivatives are positive, i.e. utility increases in all the sector-specific consumption bundles [defined by (1)].

The price index reads

$$P_{j}=\left( \int _{\omega \in \Omega _{j}}\left( p_{j}\left( \omega \right) \right) ^{1-\sigma _{j}} d\omega \right) ^{\frac{1}{1-\sigma _{j}}}\quad{\text {for}}\quad j=1,2,\ldots ,J.$$Staying true to these well-established features of modeling firms ignores a range of factors that recent empirical work has uncovered. Most importantly, works such as Manova and Zhang (2012) and Di Comite et al. (2014) have established that quality and demand (taste) shifts play an important role in explaining firm sales. Supplementary material 2 provides an extended version of the present model that takes account of quality heterogeneity and demand shifters.

We impose the parameter restriction \(k_{j}>max(2,\sigma _{j}-1)\) in order to ensure finite variance of the productivity distribution and finite expected profits prior to entry.

In more advanced models with quality heterogeneity and demand heterogeneity the relationship will be contingent on quality and demand. Accordingly, once the relation between productivity and sales is less clear, so will the relation between EPP and ESP. See Supplementary material 2 for such an extension of the model.

The observation that the dispersion of the productivity distribution is an important fundamental is also made by Helpman et al. (2004) in the context of export channel choices, i.e. their investigation of the relation between direct exports and foreign affiliate sales in various destination markets.

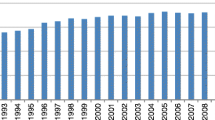

For Intra-EU exports we apply a common threshold of DKK 5.2 million for aggregate firm-level exports for each and every year. For Extra-EU exports we apply a common threshold of DKK 7500 DKK per transaction.

During the sample period the industry classification scheme changed from NACE 1.1 to NACE 2.0. We use overlapping information for both classification schemes for the years 2000–2008 to define firms’ industry at the 3-digit NACE 2.0 level.

Note that in the theoretical model labour is the only production factor. When examining total factor productivity or domestic sales instead, the distribution turns out to be very similar.

Derivations of the moments presented below are elaborated in Supplementary material 4.

To obtain market-specific elasticities of substitution, one could employ a variant of Eq. 17 substituting firm-product-destination-specific export sales for domestic sales.

The only weighting factors to obtain the aggregate we can think of are the respective firm-product-destination export sales which are in the logic of our structural model determined through selection into exporting and thus dependent on firm productivity and size.

Lawless (2009) shows that single-country destinations in the hierarchy of markets are only weakly supported in Irish data, hence we opt here for the aggregated EU+ as the primary destination.

Regression output tables for the underlying econometric estimations are available upon request.

Note that we do not curtail the universe of Danish firms but, different from e.g. ISGEP (2008), we even include very small unproductive and typically non-exporting firms, this lifts the general level of premia.

To estimate industry-by-industry ESP and EPP, we aggregate 3-digit industries 267 and 268 (NACE 2.0) to obtain sufficient industry-level observations.

References

Ackerberg, D. A., Caves, K., & Frazer, G. (2006). Structural identification of production functions. (MPRA Discussion Paper 38349). Germany: Munich Personal RePEc Archive Paper from University Library of Munich

Ackerberg, D. A., Caves, K., & Frazer, G. (2015). Identification properties of recent production function estimators. Econometrica, 83(6), 2411–2451.

Aw, B. Y., & Hwang, A. R. (1995). Productivity and the export market: a firm-level analysis. Journal of Development Economics, 47, 313–332.

Békés, G., & Muraközy, B. (2012). Temporary trade and heterogeneous firms. Journal of International Economics, 81, 232–246.

Bellone, F., Kiyota, K., Matsuura, T., Musso, P., & Nesta, L. (2014). International productivity gaps and the export status of firms: evidence from France and Japan. European Economic Review, 70, 56–74.

Bernard, A. B., Eaton, J., Jensen, J. B., & Kortum, S. (2003). Plants and productivity in international trade. American Economic Review, 93, 1268–1290.

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2007). Firms in international trade. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(3), 105–130.

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2012). The empirics of firm heterogeneity and international trade. Annual Review of Economics, 4, 283–313.

De Loecker, J. (2007). Do exports generate higher productivity? Evidence from Slovenia. Journal of International Economics, 73(1), 69–98.

De Loecker, J. (2013). Detecting learning by exporting. American Economic Journal Microeconomics, 5(3), 1–21.

Di Comite, F., Thisse, J.-F., & Vandenbussche, H. (2014). Verti-zontal differentiation in export markets. Journal of International Economics, 93(1), 50–66.

Dixit, A. K., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1977). Monopolistic competition and optimum product diversity. American Economic Review, 67(3), 297–308.

Eckel, C., Iacovone, L., Javorcik, B., & Neary, P. (2016) Testing the core competency model of multi-product firms, forthcoming: Review of International Economics.

Eckel, C., & Neary, P. (2010). Multi-product firms and flexible manufacturing in the global economy. Review of Economic Studies, 77(1), 188–217.

Farinas, J. C., & Martin-Marcos, A. (2007). Exporting and economic performance: Firm-level evidence of spanish manufacturing. World Economy, 30, 618–646.

Greenaway, D., & Kneller, R. (2007). Exporting and foreign direct investment, firm heterogeneity. The Economic Journal, 117, 134–161.

Hayakawa, K., Machikita, T., & Kimura, F. (2012). Globalization and productivity: A survey of firm-level analysis. Journal of Economic Surveys, 26(2), 332–350.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M. J., & Yeaple, S. R. (2004). Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. American Economic Review, 94, 300–316.

ISGEP - International Study Group on Exports and Productivity. (2008). ‘Understanding cross-country differences in export premia: Comparable evidence for 14 countries. Review of World Economics, 144, 596–635.

Kneller, R., & Pisu, M. (2010). The returns to exporting: Evidence from UK firms. Canadian Journal of Economics, 43(2), 494–519.

Lawless, M. (2009). Firm export dynamics and the geography of trade. Journal of International Economics, 77, 245–254.

Luttmer, E. G. (2007). Selection, growth, and the size distribution of firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1103–1144.

Manova, K., & Zhang, Z. (2012). Export prices across firms and destinations. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(1), 379–436.

Marin, A.G., & Voigtländer, N. (2013). Exporting and plant-level efficiency gains: It’s in the measure. NBER Working Paper 19033.

Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71, 1695–1725.

Merino, F. (2004). ‘Firms’ productivity and internationalization: A statistical dominance test. Applied Economics Letters, 11, 851–854.

Mrázová, M., Neary, P., & Parenti, M. (2015). Technology, demand, and the size distribution of firms. Conference Paper. Danish International Economics Workshop, Aarhus University. Accessed on April 16th–17th, 2015.

Powell, D., & Wagner, J. (2014). The exporter productivity premium along the productivity distribution: Evidence from quantile regression with nonadditive firm fixed effects. Review of World Economics, 150(4), 763–785.

Redding, S. J. (2011). Theories of heterogeneous firms and trade. Annual Review of Economics, 3, 77–105.

Schröder, P. J. H., & Sørensen, A. (2012). Second thoughts on the exporter productivity premium. Canadian Journal of Economics, 45(4), 1310–1331.

Syverson, C. (2011). What determines productivity. Journal of Economic Literature, 49(2), 326–365.

Vinzenzo, V., & Wagner, J. (2011). Robust estimation of linear fixed effects panel data models with an application to the exporter productivity premium. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik, 231(4), 546–557.

Wagner, J. (2007). Exports and productivity: A survey of the evidence from firm-level data. The World Economy, 30, 60–82.

Wagner, J. (2012). International trade and firm performance: A survey of empirical studies since 2006. Review of World Economics, 148(2), 235–267.

Acknowledgments

The paper benefited from the comments of Andrew Bernard, Gabriel Felbermayr, Benjamin Jung and Giammario Impullitti. The authors acknowledge financial support from the Tuborg Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Geishecker, I., Schröder, P.J.H. & Sørensen, A. Explaining the size differences of exporter premia: theory and evidence. Rev World Econ 153, 327–351 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-016-0266-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-016-0266-9