Abstract

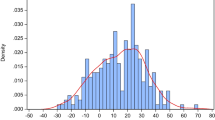

We evaluate the impact on trade of regional trade agreements (RTAs) using a panel data approach at the detailed product level which exploits exports to third destinations and imports from third origins as benchmarks. This method is robust to both endogeneity and heterogeneity across agreements and across products, and allows differentiation between the impacts of tariff provisions and non-tariff provisions. The analysis covers agricultural and food products for 74 country pairs linked by an agreement entered into force during the period 1998–2009. Our estimate of the mean elasticity of substitution across imports at product level is slightly below four. Counterfactual simulations suggest that RTAs have increased partners’ bilateral agricultural and food exports by 30–40 % on average, with marked heterogeneity across agreements. Also, RTAs are found to increase the probability of exporting a given product to a partner country although this impact is small. Finally, we found non-tariff provisions have no measurable trade impact.

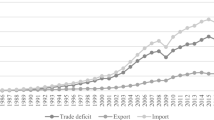

Source: Calculated by the authors from the BACI (CEPII) database, Comtrade (UN), MAcMap-HS6, and IDB data

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this article, RTAs should be understood as including preferential agreements between countries in different regions. Note that the WTO figures tend to overstate the number of active RTAs since those covering liberalization of both goods and services are counted twice by the WTO. Taking account of double-counting, the WTO registered 262 “physical” agreements in force in April 2015.

Iterative methods have been developed to carry out multi-way fixed effect estimations with unbalanced data and a large numbers of effects. However, we have in the present case both a very large number of observations, due to our product-level approach, as well as three-way fixed effects. To the best of our knowledge, this remains intractable using a Poisson regression model.

In constructing the control groups, we interpret this condition of unchanged trade policy as meaning that no RTA between the countries was signed or phased in.

A sufficient condition is that the ratio \( \tau_{iJkt} /\tau_{IJkt} \) remains constant over time. Here again, we interpret this condition of unchanged trade policy as meaning that no RTA has been signed or phased in between the countries.

It is superfluous to incorporate them explicitly since they would be perfectly correlated with the fixed effects already included. Two-way time-exporter or time-importer fixed effects are not needed either, since the corresponding shocks should be absorbed by the dependent variable transformation.

In practice, the test is based on a regression where the dependent variable is the logarithm of the squared error term, the latter being computed as the difference between trade in level and the exponential of its fitted log-value. The fitted log-trade value is used as independent variable.

The PPML estimator is efficient for λ = 1, while Gamma PML is efficient for λ = 2; however, Head and Mayer (2014) show that OLS estimates of λ such as those in this exercise, are significantly upward biased so that “estimates of λ significantly below two were a near perfect predictor of a constant variance to mean ratio” in their simulations.

This condition applies only to trade with control groups not trade between partner and reporter. The threshold was chosen based on analysis of the degree of autocorrelation of product-level trade flows. Control group trade flows are used as a benchmark to represent partner-specific trade determinants. Since these determinants are likely to be highly correlated in practice (they are linked to variables such as preferences and productivity), a low level of autocorrelation points to lack of representativeness which is likely when flows are small for two reasons: their possible overdependence on incidental factors, and the different statistical reporting thresholds used by countries. In fact, the autocorrelation of flows is significantly lower at magnitudes of below USD 200,000. See Online Appendix 2.

We ran robustness checks to deal with the minimum threshold and multiplicative factor chosen. See Table A.2 in Online Appendix 3.

With some exceptions, the estimated elasticities for the first year of implementation (not discussed or presented in this paper) are small and statistically not significant.

Zero flows are more widespread although in our context this is not immediately apparent since the dependent variable also is frequently missing, due to zeros in the control group countries’ trade flows (or—as mentioned above—to values too low to be considered representative).

A likelihood-ratio test rejects the equality of the corresponding coefficients (χ 2 = 12.4, p value <1 % in the benchmark estimation).

A likelihood-ratio test rejects the equality of the corresponding coefficients (χ 2 = 45.2, p value <1 % in the benchmark estimation).

The simulations in Fig. 1 depict the first calculation as the “conservative counterfactual”, and the second as the “upper-bound counterfactual”.

References

Angrist, J., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Baier, S. L., & Bergstrand, J. H. (2007). Do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade? Journal of International Economics, 71(1), 72–95.

Baier, S. L., Bergstrand, J. H. & Clance, M. W. (2015). Heterogeneous economic integration agreement effects (CESifo Working Papers 5488). Munich: Ifo Institute for Economic Research.

Broda, C., & Weinstein, D. E. (2006). Globalization and the gains from variety. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(2), 541–585.

Bureau, J.-C., Guimbard, H., & Jean, S. (2016). What has been left to multilateralism to negotiate On? (CEPII Working Paper, forthcoming). Paris: Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales.

Cameron, A. C., Gelbach, J. B., & Miller, D. L. (2011). Robust inference with multiway clustering. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 29(2), 238–249.

Chaney, T. (2008). Distorted gravity: Heterogeneous firms, market structure and the geography of international trade. American Economic Review, 98(4), 1707–1721.

Cipollina, M., & Salvatici, L. (2010). Reciprocal trade agreements in gravity models: A meta-analysis. Review of International Economics, 18(1), 63–80.

Dür, A., Baccini, L., & Elsig, M. (2014). The design of international trade agreements: Introducing a new dataset. The Review of International Organizations, 9(3), 353–375.

Fally, T. (2015). Structural gravity and fixed effects. Journal of International Economics, 97(1), 76–85.

Frazer, G., & Van Biesebroeck, J. (2010). Trade growth under the african growth and opportunity act. Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(1), 128–144.

Fulponi, L., Shearer, M. & Almeida, J. (2011). Regional trade agreements—treatment of agriculture. OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers 44. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Gaulier, G. & Zignago, S. (2010). BACI: International trade database at the product-level. The 1994–2007 version (CEPII Working Paper 2010–23). Paris: Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales.

Ghosh, S., & Yamarik, S. (2004). Are regional trading arrangements trade creating?: An application of extreme bounds analysis. Journal of International Economics, 63(2), 369–395.

Guimbard, H., Jean, S., Mimouni, M., & Pichot, X. (2012). MAcMap-HS6 2007, an exhaustive and consistent measure of applied protection in 2007. International Economics, 2, 99–121.

Hallak, J. C. (2006). Product quality and the direction of trade. Journal of International Economics, 68(1), 238–265.

Head, K., & Mayer, T. (2014). Gravity equations: Workhorse, toolkit, and cookbook. In G. Gopinath, E. Helpman, & K. Rogoff (Eds.), Handbook of international economics (Vol. 4, pp. 131–195). Amsterdam: Elsevier-North Holland.

Head, K., Mayer, T., & Ries, J. (2010). The erosion of colonial trade linkages after independence. Journal of International Economics, 81(1), 1–14.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M., & Rubinstein, Y. (2008). Estimating trade flows: Trading partners and trading volumes. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2), 441–487.

Kee, H.-L., Nicita, A., & Olaerreaga, M. (2008). Import demand elasticities and trade distortions. Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(4), 666–682.

Kohl, T. (2014). Do we really know that trade agreements increase trade? Review of World Economics, 150(3), 443–469.

Kohl, T., Brakman, S., & Garretsen, H. (2016). Do trade agreements stimulate international trade differently? Evidence from 296 trade agreements. The World Economy, 39(1), 97–131.

Manning, W., & Mullahy, J. (2001). Estimating log models: To transform or not to transform? Journal of Health Economics, 20(4), 461–494.

Orefice, G., & Rocha, N. (2014). Deep integration and production networks: An empirical analysis. The World Economy, 37(1), 106–136.

Romalis, J. (2007). NAFTA’s and CUSFTA’s impact on international trade. Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(3), 416–435.

Santos Silva, J. M. C., & Tenreyro, S. (2006). The log of gravity. Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(4), 641–658.

Santos Silva, J. M. C., & Tenreyro, S. (2011). Further simulation evidence on the performance of the Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimator. Economics Letters, 112(2), 220–222.

Simonovska, I., & Waugh, M. E. (2014). The elasticity of trade: Estimates and evidence. Journal of International Economics, 92(1), 34–50.

Sun, L., & Reed, M. R. (2010). Impacts of free trade agreements on agricultural trade creation and trade diversion. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 92(5), 1351–1363.

Wooldridge, J. M. (1999). Distribution-free estimation of some nonlinear panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 90(1), 77–97.

WTO. (2011). World Trade Report 2011. The WTO and preferential trade agreements: From co-existence to coherence. Geneva: WTO Publications, World Trade Organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Jean, S., Bureau, JC. Do regional trade agreements really boost trade? Evidence from agricultural products. Rev World Econ 152, 477–499 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-016-0253-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-016-0253-1