Abstract

Based on firm-level data over the period 1997–2002 for the Swedish manufacturing sector the objective of this paper is to analyze relative labor demand effects due to offshoring, separating between materials and services offshoring and also geographical location of trade partner. Overall, our results give no support to the fears that offshoring of materials or services lead to out-location of high-skilled activity in Swedish firms. Rather, this paper finds evidence that the aggregate effects from offshoring lead to increasing relative demand of high-skilled labor, mainly due to services offshoring to middle income countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Though general trade in goods by and large dominates trade in services, Lejour and Smith (2008) point out that in many OECD countries almost 40 % of manufacturing employment could actually be considered as working with services. So, even though we focus on the manufacturing sector, it is important to consider both materials and services offshoring.

Balsvik and Birkeland (2012) estimate a Mincer equation and focus on the offshoring impact on wages at the firm level in Norway.

In an early working paper version, we experimented with the same three skill categories as Ekholm and Hakkala (2006). Since skills include not only educational attainment but also work experience we found it easier to argue that there is a clear distinction between individuals with post upper secondary education than workers with less education compared to allowing for more skill categories where the distinction is less clear. See also footnote 17.

In a small open economy such as Sweden, the relative price effect is zero since terms of trade are fixed.

It could be argued that the supply of labor has increased in Sweden during the time of study. However, according to Bandick and Hansson (2009) it appears as if demand factors of labor are more important than supply factors explaining the increase in labor in Sweden, while Eliasson et al. (2012) show that both the relative supply and demand for skilled labor have increased after 2003, with a much more pronounced shift in supply.

Acemoglu et al. (2015) discuss the relationship between offshoring and wages as an inverted U-relationship which means that the factor-biased technical change induced by offshoring may shift in the direction of the other factor once offshoring becomes sufficiently large and thus closes the wage gap.

The key used in Baldwin and Robert-Nicoud (2014) to integrate offshoring in the standard Heckscher–Ohlin modeling is to view offshoring as migration, or rather ‘shadow migration’, where factors employed in the source country (Foreign) are treated as if they had actually migrated to Home (the offshoring nation) but are still paid the factor prices in Foreign.

World Trade Organization and IDE-JETRO (2011, p. 84).

See Berndt (1991, chap. 9) for a complete derivation.

We are grateful to Roger Bandick and Pär Hansson for providing us with industry-level relative wages. See Bandick and Hansson (2009) for a description of how these relative wages are constructed.

Wages are obviously endogenous in Eq. (1). By using industry-level data we reduce the risk of endogeneity. However, it can well be argued that some endogeneity may remain since our sample consists of larger firms (more than 50 employees). If the firms in our sample are dominant enough to affect (or even set) the wage structure of the whole industry, then the endogeneity problem remains. We therefore opted for using relative wages at a rather high industry aggregation level (two-digit level) to remove as much of the problem as possible.

The cut off level at an average of 50 employees means that some firms actually exit the sample at some point during the study period due to variations in average number of employees over time. As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, offshoring could be part of the story explaining the reduction in firm-level employment leading to a probable selection bias due to the cut off. We have therefore checked for the variation of total intermediate trade by year and number of employees for observations deleted due to the threshold. Average number of employees appears to be stable at around 35 during the study period and there is no trend of an increase in offshoring. On the contrary, 25 % of the dropped observations report zero offshoring. Further, we have re-run the regression with a balanced panel consisting of firms that have more than 50 employees throughout the study period. The main result of the paper remains robust, which indicates that the results are not driven by firms at the border of the cut-off level.

As an alternative proxy for technological change we have used the firm-level share of technicians, which would allow us to also include small firms in the dataset. However, this proxy is highly correlated with skilled labor, which makes it difficult to obtain reliable results.

Though dividing skill according to educational attainment is probably more appropriate than using classification according to production/non-production workers or operatives/non-operatives, there are problems with using educational attainment as well. The main problem is concerned with work experience which is not included in such a measure and which would improve skill capacity. By dividing labor into only two groups, high and low-skilled, we hopefully minimize the problem since it is reasonable to believe that there is a larger skill step between labor with and without post-secondary education than, e.g., between labor with and without secondary education.

We note that there is a high correlation between the broad and narrow definitions of material offshoring; the simple correlation is 0.9916.

Unfortunately, as Sweden became a member of the European Union (EU) in 1995 the classification of origin of imports has been affected and imports originating from a country outside of the EU but cleared through customs in another EU country are now registered as imports from the transit EU country. According to Statistics Sweden this means that imports from outside of EU are likely underestimated. This is especially important to keep in mind when we separate between sourcing regions, since especially imports from low income countries will probably be underestimated.

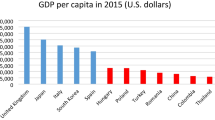

Exchange rate SEK/USD = 8.424 reported by the Swedish Central Bank on February 13, 2015.

As from 2003, the settlement system is no longer used as source for services trade data. Statistics Sweden is instead the official provider of services trade data and they collect data from a representative sample, which amounts to approximately 10 % of the population of Swedish firms with international trade. Though with the intention to improve data quality, the change in data collection method came to the cost of a large reduction in number of firms that can be followed over time (except for the largest firms in each industry) and a time series break in services trade data in 2003 with no overlapping between the two time periods.

Differences between country names used by Statistics Sweden and the World Bank have been considered, and we have made necessary adjustments such as adding Taiwan as a province to China and classifying small islands within the governor country.

Using imports of intermediates as a share of output, value added or total inputs is now the standard way of measuring the intensity of offshoring; see, e.g., the review by Crinò (2009).

Original BEC was first issued in 1971 by United Nations Statistics Division and revised three times. We have used the third revision.

In addition, Pierce and Schott (2012) point out alterations in product categories in different years, which we handle by using the concordance methodology by Van Beveren et al. (2012). The HS has been updated four times (in 1992, 1996, 2002 and 2007) and Combined Nomenclature classification from which we derived HS codes, is revised yearly. Due to the inclusion of 2002 in our analysis, we have checked time consistency of the product groups. The BEC structure turned out to be unchanged for our time period. Van Beveren et al. (2012) provide time consistent concordance tables by using algorithms of Pierce and Schott (2012) and existing concordance tables provided by Eurostat (EU’s classification metadata server).

A closer look at the top 5 source countries for Swedish manufacturing firms in each region shows the following. Materials offshoring: from high income countries (Germany, the UK, Norway, France, Denmark), from middle income countries (China, Russia, Iran, Latvia, Brazil), and from low income countries (Egypt, Indonesia, India, Nigeria, Philippines). Services offshoring: from high income countries (the US, the UK, Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark), from middle income countries (China, Mexico, Turkey, Russia, Brazil), and from low income countries (India, Egypt, Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam).

According to descriptive statistics there are three observations with rather high values on offshoring of materials and one observation with a rather high value on services offshoring, which is evident in Table 2. To test the robustness of our results we also estimate Eq. (1) excluding these observations. It turns out that the results are not sensitive to these observations and we therefore include them in the estimations presented in the next section in Tables 4 and 5.

There was a major structural change in the Swedish textile and apparel industry during the 1980s and 1990s. According to Gullstrand (2005) many jobs were destroyed and relocated to other sectors. The remaining and entering firms in this industry proved to be more skill intensive and productive than exiting firms.

The United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database (UN Comtrade) reports imports and exports statistics reported by statistical authorities of around 200 countries by SITC or HS product grouping codes. The time span of the annual trade data is 1962 to the most recent year. Yearly currency conversion factors are available.

For some firms we lack data on instruments. There are two reasons for this: first, some firms report zero sales for some years; second, there are gaps in the COMTRADE database as countries (if they exist in the database) do not necessarily report their trade statistics for every year. The COMTRADE database does not use interpolate values of trade to fill in gaps. Further, to avoid using same information in the instrument as the original offshoring variable, we used 1-year lagged information of offshoring in construction of instruments. For these reasons, the number of observations varies in the IV estimates. Non-reported robustness checks show that the differences in the number of observations do not affect our results.

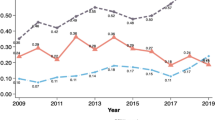

Data are collected from International Telecommunication Union, World Telecommunication/ICT Development Report and database and World Bank estimates.

The results in Table 5, where we distinguish between regions for sourcing intermediate materials and services, should be treated with some caution. The null hypothesis of the Sargan test is rejected at the 10 % significance level, indicating some doubt about the validity of the instruments. This is probably due to the complexity of dimensions, where the treatment effects picked up by these disaggregate instruments might be different. The performance of the IV estimator in the case of less relevant instruments is questioned in the empirical literature for multiple regressors and/or multiple instruments cases (Bound et al. 1995; Shea 1997; Staiger and Stock 1997).

China has long been considered the cheapest production site in the world, but has faced increasing costs along with economic growth. Based on this development in costs, Fang et al. (2010) present four cases of Swedish firms sourcing to China to disentangle why the firms don’t opt out and search for new ventures. They find that firms with long-term strategic intents and high levels of ethics and social corporate responsibility stay in China, while those who are mainly cost-driven would change sourcing partner.

References

Acemoglu, D., Gancia, G., & Zilibotti, F. (2015). Offshoring and directed technical change. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 7(3), 84–122.

Amiti, M., & Wei, S.-J. (2005). Service outsourcing, productivity and employment: Evidence from the US (IMF Working Paper No. WP 05/238). Washington DC: International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Anderton, B., & Brenton, P. (1999). Outsourcing and low-skilled workers in the UK (CSGR Working Paper No. 12/98). Coventry: University of Warwick.

Antràs, P., Garicano, L., & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2006). Offshoring in a knowledge economy. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(1), 31–77.

Autor, D., & Dorn, D. (2009). This job is “getting old”: Measuring changes in job opportunities using occupational age structure. American Economic Review, 99(2), 45–51.

Baldwin, R., & Robert-Nicoud, F. (2014). Trade-in-goods and trade-in-tasks: An integrating framework. Journal of International Economics, 92(1), 51–62.

Balsvik, R., & Birkeland, S. (2012). Offshoring and wages: Evidence from Norway. Bergen: Mimeo, Norwegian School of Economics.

Bandick, R., & Hansson, P. (2009). Inward FDI and demand for skills in manufacturing firms in Sweden. Review of World Economics/WeltwirtschaftlichesArchiv, 145(1), 111–131.

Baumgarten, D., Geishecker, I., & Görg, H. (2013). Offshoring, tasks, and the skill-wage pattern. European Economic Review, 61, 132–152.

Becker, S. O., Ekholm, K., & Nilsson Hakkala, K. (2010). Produktionen flyttar utomlands? Om offshoring och arbetsmarknaden. Stockholm: SNS Förlag.

Berman, E., Bound, J., & Griliches, Z. (1994). Changes in the demand for skilled labor within US manufacturing: Evidence from the annual survey of manufacturers. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109(2), 367–397.

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., & Schott, P. K. (2006). Transfer pricing by US-based multinational firms (NBER Working Paper No. 12493). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Berndt, E. R. (1991). The practice of econometrics: Classic and contemporary. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Birkinshaw, J., Braunerhjelm, P., Holm, U., & Terjesen, S. (2006). Why do some multinational corporations relocate their headquarters overseas? Strategic Management Journal, 27(7), 681–700.

Bound, J., Jaeger, D. A., & Baker, R. (1995). Problems with instrumental variables estimation when the correlation between the instruments and the endogenous explanatory variable is weak. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90(430), 443–450.

Civril, D. (2011). The impacts of technology and material offshoring on different labor types: An analysis using microlevel data. In Paper presented in the 10th annual GEP postgraduate conference.

Crinò, R. (2009). Offshoring, multinationals and labour market: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 23(2), 197–249.

Crinò, R. (2010). Service offshoring and white-collar employment. Review of Economic Studies, 77(2), 595–632.

Cristea, A. D., & Nguyen, D. X. (2015). Transfer pricing by multinational firms: New evidence from foreign firm ownerships. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy (forthcoming).

Egger, H., & Egger, P. (2003). Outsourcing and skill-specific employment in a small economy: Austria after the fall of the iron curtain. Oxford Economic Papers, 55(4), 625–643.

Ekholm, K., & Hakkala, K. (2006). The effect of offshoring on labor demand: Evidence from Sweden (Working Paper No 654). Stockholm: Research Institute of Industrial Economics.

Eliasson, K., Hansson, P., & Lindvert, M. (2012). Globala värdekedjor och internationell konkurrenskraft (Growth analysis) (Working Paper No. 2012:23). Stockholm: Growth Analysis (in Swedish).

Falk, M., & Koebel, B. M. (2002). Outsourcing, imports and labour demand. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 104(4), 567–586.

Fang, T., Gunterbeg, C., & Larsson, E. (2010). Sourcing in an increasingly expensive China: Four Swedish cases. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(1), 119–138.

Feenstra, R. C., & Hanson, G. H. (1996a). Foreign investment, outsourcing and relative wages. In R. C. Feenstra, G. M. Grossman, & D. A. Irwin (Eds.), Political economy of trade policy: Essays in honor of Jagdish Bhagwati (pp. 89–127). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Feenstra, R. C., & Hanson, G. H. (1996b). Globalization, outsourcing, and wage inequality. American Economic Review, 86(2), 240–245.

Feenstra, R. C., & Hanson, G. H. (1999). The impact of outsourcing and high-technology capital on wages: Estimates for the United States, 1979–1990. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 907–940.

Fors, M., & Jansson, R. (2006). Handel med varor och tjänster (Statistics Sweden, internal background memorandum NA/UI). Stockholm: Statistics Sweden (SCB) (in Swedish).

Freund, C., & Weinhold, D. (2002). The internet and international trade in services. American Economic Review, 92(2), 236–240.

Geishecker, I. (2008). The impact of international outsourcing on individual employment security: A micro-level analysis. Labour Economics, 15(3), 291–314.

Görg, H., Greenaway, D., & Kneller, R. (2008). The economic impact of offshoring (GEP Research Report). Nottingham: University of Nottingham.

Görg, H., & Hanley, A. (2005). Labour demand effects of international outsourcing: Evidence from plant-level data. International Review of Economics and Finance, 14(3), 365–376.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (2005). Outsourcing in a global economy. Review of Economic Studies, 72(1), 135–159.

Grossman, G. M., & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2008). Trading tasks: A simple theory of offshoring. American Economic Review, 98(5), 1978–1997.

Grossman, G. M., & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2012). Task Trade between similar countries. Econometrica, 80(2), 593–629.

Gullstrand, J. (2005). Industry dynamics in the Swedish textile and wearing apparel sector. Review of Industrial Organization, 26(3), 349–370.

Gupta, A., & Sao, D. (2009). Anti-offshoring legislation and United States federalism: The constitutionality of federal and state measures against global outsourcing of professional services. Texas International Law Journal, 44(4), 629–663.

Hansson, P. (2005). Skill upgrading and production transfer within Swedish multinationals. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 107(4), 673–692.

Hansson, P., Karpaty, P., Lundberg, L., Poldahl, A., & Yun, L. (2007). Svenskt näringsliv i en globaliserad värld: Effekter av internationaliseringen på produktivitet och sysselsättning (ITPS A2007:004). Östersund: The Swedish Institute for Growth Policy Studies (ITPS).

Hijzen, A., Görg, H., & Hine, R. C. (2005). International outsourcing and the skill structure of labour demand in the United Kingdom. Economic Journal, 115(506), 860–878.

Hijzen, A., Pisu, M., Upward, R., & Wright, P. W. (2011). Employment, Job turnover, and trade in producer services: UK firm-level evidence. Canadian Journal of Economics, 44(3), 1020–1043.

Hummels, D., Jørgensen, R., Munch, J., & Xiang, C. (2014). The wage effects of offshoring: Evidence from Danish matched worker-firm data. American Economic Review, 104(6), 1597–1629.

Kurz, C. J. (2006). Outstanding outsourcers: A firm and plant level analysis of production sharing (Working Paper). Washington, DC: Federal Reserve Board.

Lejour, A., & Smith, P. (2008). International trade in services. Editorial introduction. Journal of Industry Competition and Trade, 8(3), 169–180.

Liu, R., & Trefler, D. (2008). Much ado about nothing: American jobs and the rise of service outsourcing to China and India (NBER Working Paper No. 14061). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Lo Turco, A., & Maggioni, D. (2012). Offshoring to high and low income countries and the labor demand: Evidence from Italian firms. Review of International Economics, 20(3), 636–653.

Machin, S., & van Reenen, J. (1998). Technology and changes in skill structure: Evidence from seven OECD countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(4), 1215–1244.

Mattoo, A., & Stern, R. M. (2008). Overview. In A. Mattoo, R. M. Stern, & G. Zanini (Eds.), A handbook of international trade in services. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Michel, B., & Rycx, F. (2012). Does offshoring of materials and business services affect employment? Evidence from a small open economy. Applied Economics, 44(2), 229–251.

Miles, I. (2006). Innovation in services. In J. Fagerberg, D. Mowery, & R. Nelson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mion, G., & Zhu, L. (2013). Import competition from and offshoring to China: A curse or blessing for firms? Journal of International Economics, 89(1), 202–215.

Moser, C., Urban, D. M., & di Mauro, B. W. (2009). Offshoring, firm performance and establishment-level employment: Identifying productivity and downsizing effects (CEPR Discussion Paper No. 7455). London: Centre for Economic Policy Research (CPER).

OECD. (1999). Classifying educational programmes: Manual for ISCED-97 implementation in OECD countries. Paris: OECD.

Pierce, J. R., & Schott, P. K. (2012). Concording US harmonized system categories over time. Journal of Official Statistics, 28(1), 53–68.

Senses, M. Z. (2010). The effects of offshoring on the elasticity of labor demand. Journal of International Economics, 81(1), 89–98.

Shea, J. (1997). Instrumental relevance in linear models: A simple measure. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 79(2), 348–352.

Staiger, D., & Stock, H. (1997). Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica, 65(3), 557–586.

Strauss-Kahn, V. (2004). The role of globalization in the within-industry shift away from unskilled workers in France. In R. E. Baldwin & E. D. Winters (Eds.), Challenges to globalization: Analysing the economics (NBER Conference Report), Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Svensson, M. (2005). Överbryggning av tidsseriehacket mellan 2002 och 2003 (Internal background memorandum STE/APP). Stockholm: Swedish Central Bank (Sveriges Riksbank) (in Swedish).

Van Beveren, I., Bernard, A. B., & Vandenbussche, H. (2012). Concording EU trade and production data over time (NBER Working Paper No. 18604). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Wagner, J. (2011). Offshoring and firm performance: Self-selection, effects on performance, or both? Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 147(2), 217–247.

World Trade Organization and IDE-JETRO. (2011). Trade patterns and global value chains in East Asia: From trade in goods to trade in tasks. Geneva: WTO.

Yeats, A. J. (1998). Just how big is global production sharing? (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 1871). Washington DC: World Bank.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank an anonymous reviewer, Joakim Gullstrand, Pär Hansson, Patrik Gustavsson Tingvall, and seminar participants at the Canadian Economic Association meetings, The Swedish National Board of Trade, Umeå University, and Örebro University for valuable comments on a previous version of the paper. We are grateful to the Swedish Central Bank (Riksbanken) for providing data on service imports. Financial support from the Jan Wallander and Tom Hedelius Foundation is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11.

About this article

Cite this article

Andersson, L., Karpaty, P. & Savsin, S. Firm-level effects of offshoring of materials and services on relative labor demand. Rev World Econ 152, 321–350 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-015-0243-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-015-0243-8