Abstract

Understanding the dynamics of import prices is an important but challenging issue that affects our assessment of welfare. We propose an exact import price index by extending the analysis of Broda and Weinstein (Q J Econ 121(2):541–585, 2006), who include growth in product variety in their calculations of import prices. While still relying on Armington’s (Int Monet Fund Staff Pap 16(1):159–178, 1969) definition of variety, we relax two assumptions, allowing the set of products and unobserved taste and quality parameter to vary. Our modified import price index shows that gains from variety in European G7 countries, although positive, are small compared with gains from taste and quality. Using food and tobacco products as a benchmark with unchanged taste and quality, we find significant gains from shifts in consumer preferences and improving quality for Germany, France, Italy and the UK between 1995 and 2012. By comparing results based on different benchmark groups we further flag the importance of consumer taste in international trade.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We choose four European G7 countries as an object of our investigation, however, the framework is easily applicable to any other reporting country in the database.

See Diewert (1993) for more details.

Actually, Feenstra (1994) defines I g as a strict subset of the varieties available in periods t and t − 1: \( I_{g} \subseteq (I_{gt} \cap I_{gt - 1} ) \). This allows to use Feenstra’s (1994) approach to control for possible changes in taste and quality by excluding corresponding varieties from I g . Same variety with changing taste or quality is simply treated as two different varieties. For the same reason Feenstra (1994) exclude imports from developing countries and Japan during his calculations, arguing that these countries may have changed the quality of their products over the period of estimation.

Although Feenstra’s (1994) framework allows to control changes in taste and quality in general, it requires to make a distinction between varieties with constant taste and quality (included in I g ) and changing taste and quality (excluded from I g ). Broda and Weinstein (2006) define that \( I_{g} = (I_{gt} \cap I_{gt - 1} ) \), thus assuming that quality and taste should be unchanged for all varieties imported in both periods.

Benkovskis and Rimgailaite (2011) use this approach to evaluate the relative quality with respect to a benchmark—imports from Germany.

The alternative way to achieve the same results is to exclude all varieties and products from I g and G t,t−1 except for imports of benchmark product j from country k (variety, for which we assume unchanged quality and taste, ∆d jkt = 0). Then one can apply Feenstra’s (1994) methodology. However, our approach summarised in (11) and (13) has two advantages. First, Eqs. (11) and (13) have a clear economic intuition, thus allowing to explain the evaluated changes in taste and quality. Second, our approach is superior in case of a broad benchmark (see Sect. 5.1). We can allow for unchanged average taste and quality for a broad product category (e.g. food and tobacco products), while taste and quality of individual varieties within benchmark category (e.g. fruits from Italy or meet from Spain) can vary. This is not possible in Feenstra’s (1994) framework, as it requires unchanged taste and quality for all varieties included in I g .

This sample of partners provides a representative picture of overall imports, as it covers between 87.6 % of total imports in Italy and 95.2 % of total imports in Germany in 2012.

More information on reclassifications of Combined Nomenclature can be found in http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/ramon/nomenclatures/.

An observation is treated as an outlier if its unit value index deviates from the category median in a particular year by more than four median absolute deviations. The exclusion of outliers does not significantly reduce the coverage of the database. For example, in 2012 outliers accounted for only 0.2 % of total value in Germany, 0.3 % in France, 0.9 % in Italy and 0.7 % in the UK.

Similar results about the decline of the number of imported products are made by Mohler and Seitz (2012), who analyse disaggregated imports of EU-27 countries between 1999 and 2008.

These results are also confirmed by Mohler and Seitz (2012), who reported an increase in the mean number of countries for all EU-27 members between 1999 and 2008.

It can be argued, however, that the quality and taste parameter can implicitly enter the residual of both, the demand Eq. (15) as well as the supply Eq. (16). This is more likely when quality reflects some tangible properties of a product and as such increases the production costs of the high-qualitative product. This problem cannot be addressed without a well derived supply side in the model therefore we leave this question to further research.

The number of products for which this condition is met can be read from Table 3. Although the coverage is reduced, it still remains reasonably high and ranges between 74.3 % of total aggregated imports for the UK and 83.5 % for France in 2012 although we restricted ourselves to 50 partner countries, excluded outliers and required at least 3 countries of origin.

They report a median elasticity of 3.7 for the period between 1972 and 1988 for seven-digit (TSUSA) goods and 3.1 for the period between 1990 and 2001 for 10-digit (HTS) goods.

Mohler and Seitz (2012) report a mean elasticity of 4.67 for Germany, 4.22 for France, 4.60 for Italy and 3.84 for the UK.

Perhaps the proper choice of the benchmark is a topic for a separate research and should be done together with sectoral experts on the basis of firm-level data. Here we just demonstrate the essence of the methodology and empirical results under reasonable assumptions.

In 2006–2009 it even decreases to approximately 65–70 % for France and Italy.

Price dynamics shows different pattern for the UK due to changes in GBP/EUR exchange rate. Note that price index changes are reported in GBP for the UK.

The bias from changes in variety is calculated as \( \prod\nolimits_{{g \in G_{t,t - 1} }} {(\lambda_{gt} /\lambda_{gt - 1} )^{{w_{gt} /1 - \sigma_{g} }} - 1} . \)

One should keep in mind that we always construct the intersection of consecutive variety sets I g relative to previous year, while Broda and Weinstein (2006) and Mohler and Seitz (2012) use a base year. The difference between two approaches can be intuitively compared with difference between chain-linked GDP and GDP in prices of a base year. However, our findings do not alter qualitatively if we follow Broda and Weinstein (2006) approach and use 1995 as a base year. In this case changes in variety between 1995 and 2012 produce positive import price bias of 0.8 % for Germany, 3.4 % for France, 2.7 % for Italy and 0.4 % for the UK.

Again, despite higher degree of openness of European countries, gain figures are lower compared to the estimates of Broda and Weinstein (2006) for the US, where gains from varieties are found to be 2.6 % of GDP (between 1972 and 2001) or about 0.1 % of income each year.

The bias from changes in the set of goods is calculated as \( (\Lambda_{t} /\Lambda_{t - 1} )^{ - 1} - 1 \).

The bias from changes in quality is calculated as \( \prod\nolimits_{{g \in G_{t,t - 1} }} {\Delta d_{gt}^{{w_{gt} /\sigma_{g} - 1}} } - 1. \)

Although these changes in γ seem to be small, one should remember that it is γ − 1 and (γ − 1)/γ that enter the model. Even marginal changes in low elasticity of substitution mean significant difference in market characteristics.

Here we see the possibility to join our approach with the method of Sheu (2011). Information on product characteristics will give an opportunity to evaluate quality changes for several product groups using logit regression from Sheu (2011). These groups can then serve as the benchmark, while the quality of other products relative to the benchmark could be assessed using Eqs. (11) and (12).

References

Amiti, M., & Khandelwal, A. K. (2013). Import competition and quality upgrading. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(2), 476–490.

Armington, P. S. (1969). A theory of demand for products distinguished by place of production. International Monetary Fund Staff Papers, 16(1), 159–178.

Benkovskis, K., & Rimgailaite, R. (2011). The quality and variety of exports from the new EU member states: Evidence from very disaggregated data. Economics of Transition, 19(4), 723–747.

Bloningen, B. A., & Soderbery, A. (2010). Measuring the benefits of foreign product variety with an accurate variety set. Journal of International Economics, 82(2), 168–180.

Broda, C., Greenfield, J., & Weinstein, D. E. (2006). From groundnuts to globalization: A structural estimate of trade and growth. (NBER Working Paper 12512). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Broda, C., & Weinstein, D. E. (2006). Globalization and the gains from variety. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(2), 541–585.

Di Comite, F., Thisse, J. F., & Vandenbussche, H. (2012). Verti-zontal differentiation in monopolistic competition. (CEPR Discussion Paper 8752). London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Diewert, W. E. (1993). The economic theory of index numbers: A survey. In W. E. Diewert & A. O. Nakamura (Eds.), Essays in index number theory (Vol. 1, pp. 177–221). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Dixit, A. K., & Stiglitz, J. E. (1977). Monopolistic competition and optimum product diversity. American Economic Review, 67(3), 297–308.

Eurostat (2011). PEEIs in focus. A summary for the import price index. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Feenstra, R. C. (1994). New product varieties and the measurement of international prices. American Economic Review, 84(1), 157–177.

Feenstra, R. C., & Romalis, J. (2012). International prices and endogenous quality. (NBER Working Paper 18314). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Flam, H., & Helpman, E. (1987). Vertical product differentiation and north–south trade. American Economic Review, 77(5), 810–822.

Hallak, J. C., & Schott, P. K. (2011). Estimating cross-country differences in product quality. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(1), 417–474.

Hummels, D., & Klenow, P. J. (2005). The variety and quality of a nation’s exports. American Economic Review, 95(3), 704–723.

Khandelwal, A. (2010). The long and short (of) quality ladders. Review of Economic Studies, 77(4), 1450–1476.

Krugman, P. R. (1979). Increasing returns, monopolistic competition, and international trade. Journal of International Economics, 9(4), 469–479.

Krugman, P. R. (1980). Scale economies, product differentiation, and the pattern of trade. American Economic Review, 70(5), 950–959.

Leamer, E. E. (1981). Is it a demand curve, or is it a supply curve? Partial identification through inequality constraints. Review of Economics and Statistics, 63(3), 319–327.

Mohler, L. (2009). On the sensitivity of estimated elasticities of substitution. (FREIT Working Paper 38). Forum for Research on Empirical International Trade, Polytechnic University of Marche.

Mohler, L. (2011). Four essays on international trade in variety. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Basel.

Mohler, L., & Seitz, M. (2012). The gains from variety in the European Union. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 148(3), 475–500.

Phillips, P. W., & McNeil, H. (2000). A survey of national labelling policies for GM foods. AgBioForum, 3(4), 219–224.

Pierces, J. R., & Schott, P. K. (2009). Concording U.S. harmonized system categories over time. (NBER Working Paper 17837). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Romer, P. M. (1994). New goods, old theory, and the welfare costs of trade restrictions. (NBER Working Paper 4452). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Sato, K. (1976). The ideal log-change index number. Review of Economics and Statistics, 58(2), 223–228.

Sheu, G. (2011). Price, quality, and variety: Measuring the gains from trade in differentiated products. Mimeo: US Department of Justice. http://people.virginia.edu/~jh4xd/Workshop%20papers/Sheu_printer_demand_sept_2011.pdf. (Accessed December 20, 2011).

Soderbery, A. (2010). Investigating the asymptotic properties of import elasticity estimates. Economics Letters, 109(2), 57–62.

Soderbery, A. (2013). Estimating import supply and demand elasticities: Analysis and implications. Mimeo: Department of Economics, Purdue University. http://web.ics.purdue.edu/~asoderbe/Papers/soderbery_elasticity.pdf. (Accessed December 14, 2013).

Vartia, Y. (1976). Ideal log-change index numbers. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 3(3), 121–126.

Acknowledgments

We thank Vesna Corbo, David Hummels, Mihaly Andras Kovacs, William Powers, participants of an internal Oesterreichische Nationalbank research seminar, the 13th European Trade Study Group conference in Copenhagen and the ECB Expert Meeting on “Assessing Competitiveness” in September 2011 as well as anonymous referee for their valuable comments and recommendations. The authors assume responsibility for any errors and omissions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

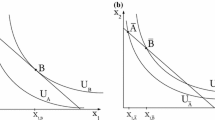

Distribution of elasticities of substitution (elasticities of substitutions estimated using hybrid LIML estimator for all products where data on at least three countries of origin are available. The number of observations is 6,659 for Germany, 6,673 for France, 6,386 for Italy and 6,382 for the UK). Source: Authors’ calculations based on Eurostat Comext

Comparison of officially published import prices and calculations from disaggregated data (annual changes, %) (conventional import price index is calculated from disaggregated import data (eight-digit CN classification level, 50 partner countries) using Eqs. (7) and (8). All prices for the UK are in GBP terms). Source: Eurostat, Authors’ calculations based on Eurostat Comext. a Germany, b France, c Italy, d UK

About this article

Cite this article

Benkovskis, K., Wörz, J. How does taste and quality impact on import prices?. Rev World Econ 150, 665–691 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-014-0196-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-014-0196-3