Abstract

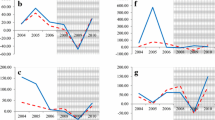

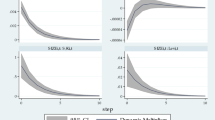

The model and related empirical examination in this paper demonstrate one reason why previous studies document both positive and negative correlations between exchange rate volatility and observed levels of foreign direct investment. Using a simple model of cross-border mergers and acquisitions, it argues that the source of the volatility is important in resolving the puzzle. An empirical analysis of mergers and acquisitions by individual firms reveal that first-time foreign direct investment is discouraged by monetary volatility originating from the source-country, but can be encouraged by monetary volatility originating in the host country, especially when compared to domestic investment or expansion by existing multinationals. The regressions also reveal a large and positive “euro effect” on the number of first-time cross-border mergers within the European Monetary Union, even when controlling for domestic merger activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Please see Phillips and Ahmadi-Esfahani (2008) for a detailed survey of the theoretical and empirical literature on exchange rate volatility and FDI.

Veteran foreign investors are firms who have already acquired one firm in a particular country outside their native market and are making additional acquisitions there.

Setting the mean of money supply shocks to equal \(-{\frac{\sigma_{M}^{2}}{2}}\) imposes a mean-preserving spread. Our results also hold qualitatively with mean zero shocks.

To see this, one rearranges the first-order condition to isolate i t . It is equal to to the inverse of \(\left( {\frac{M_{t}}{\chi P_{t}}}-1\right) \), which itself is a shifted log-normal random variable with variance σ 2 M .

See “Appendix 2” for first-order conditions. Results are qualitatively the same even if a constant discount factor is used.

See “Appendix 1” for derivation.

P* is affected indirectly, through changes in \(\hat{\varphi}_{h}^{\ast}.\)

For the case of logarithmic preferences, where ρ = 1, both lines in this graph would be flat and home interest rate volatility would have no effect on either variable.

See “Appendix 4” for a summary of the data. The countries are Australia, Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Hungary and Greece are dropped from the final analysis due to limited availability of data used to calculate interest rate volatility during a sufficient portion of our sample period.

In unreported regressions, the results are also robust to IV estimation (with host and source GDP and interest rates used as IV regressors for interest rate volatility) with a full set of gravity variables from the CEPII data set used by Head et al. (2010). GMM results are robust to including the subset of gravity variables that is significant (including all 18 amounts to too many regressors for our relatively short time series).

A specification test including \(\ln ({\frac{n_{f}}{n_{h}}})\) as a regressor in the PQML regressions yields a coefficient different from 1, indicating that running the regressions on ratios as in the earlier analysis is not a useful robustness exercise.

Two additional factors that may underly the exchange rate volatility-FDI puzzle are (1) financial flows involved in overseas investment and repatriated profits may themselves influence the exchange rate, as suggested by the literature on valuation effects and (2) firms’ sensitivity to risk in exchange rates and any fundamental variables that may drive them can depend on whether they are investing to sell goods locally or for export, as suggested by Burstein et al. (2008). Both directions provide plentiful ground for future research.

Graphic available upon request.

References

Alaba, O. B. (2003). Exchange rate uncertainty and foreign direct investment in Nigeria. Presented at the WIDER conference on sharing global prosperity, Helsinki, Finland (September 6–7).

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Pozo, S. (2001). Foreign exchange rates and foreign direct investment in the United States. International Trade Journal, 15(3), 323–343.

Bacchetta, P., & van Wincoop, E. (2000). Does exchange-rate stability increase trade and welfare? American Economic Review, 90(5), 1093–1109.

Bergin, P. R., & Corsetti, G. (2008). The extensive margin and monetary oolicy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 55(7), 1222–1237.

Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., & Schott, P. K. (2006). Trade costs, firms, and productivity. Journal of Monetary Economics, 53(5), 917–937.

Burstein, A., Kurtz, C., & Tesar, L. (2008). Trade, production sharing, and the international transmission of business cycles. Journal of Monetary Economics, 44(4), 775–795.

Campa, J. M. (1993). Entry by foreign firms in the United States under exchange rate uncertainty. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 75(4), 614–622.

Chakrabarti, R., & Scholnick, B. (2002). Exchange rate regimes and foreign direct investment flows. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv/Review of World Economics, 138(1), 1–21.

Chari, V. V., Kehoe, P. J., & McGrattan, E. R. (2002). Can sticky price models generate volatile and persistent real exchange rates? Review of Economic Studies, 69(3), 533–563.

Cushman, D. O. (1988). Exchange-rate uncertainty and foreign direct investment in the United States. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv/Review of World Economics, 124(2), 322–335.

Cushman, D. O. (1985). Real exchange rate risk, expectations, and the level of direct investment. Review of Economics and Statistics, 67(2), 297–308.

Dixit, A., & Pindyck, R. S. (1994). Investment under uncertainty. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Engel, C., & Mark, N. C., & West, K. (2008). Exchange rate models are not as bad as you think. In A. Acemoglu, K. Rogoff, & M. Woodford (Eds.), NBER macroeconomics annual (Vol. 22). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Galgau, O., & Sekkat, K. (2004). The impact of the single market on foreign direct investment in the European Union. In: L. Michelis & M. Lovewell (Eds.), Exchange rates, economic integration and the international economy. Toronto: APF Press.

Ghironi, F., & Melitz, M. J. (2005). International trade and macroeconomic dynamics with heterogeneous firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(3), 865–915.

Goldberg, L. S., & Kolstad, C. D. (1995). Foreign direct investment, exchange rate variability, and demand uncertainty. International Economic Review, 36(4), 855–873.

Head, K., Mayer, T., & Ries, J. (2010). The erosion of colonial trade linkages after independence. Journal of International Economics, 81(1), 1–14.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M. J., & Yeaple, S. R. (2004). Exports versus FDI. American Economic Review, 94(1), 300–316.

International Monetary Fund. (2007). International financial statistics CD-ROM. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund Producer and Distributor.

Nocke, V., & Yeaple, S. R. (2007). Cross-border mergers and acquisitions versus greenfield foreign direct investment: The role of firm heterogeneity. Journal of International Economics, 72(2), 336–365.

Obstfeld, M., & Rogoff, K. (1998). Risk and exchange rates. (NBER working paper no. 6694). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Phillips, S., & Ahmadi-Esfahani, F. Z. (2008). Exchange rates and foreign direct investment: Theoretical models and empirical evidence. Australian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 52(4), 505–525.

Russ, K. N. (2007). The endogeneity of the exchange rate as a determinant of FDI: A model of entry and multinational firms. Journal of International Economics, 71(2), 344–372.

Schmidt, C. W., & Broll, U. (2009). Real exchange rate uncertainty and US foreign direct investment: An empirical analysis. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 145(3), 513–530.

Silva, K. M. C., & Tenreyro, S. (2006). The log of gravity. Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(4), 641–658.

Zhang, L. H. (2004). European integration and foreign direct investment. In C. Tsoukis, G. M. Agiomirgianakis, & T. Biswas (Eds.), Aspects of globalization: Macroeconomic and capital market linkages in the integrated world economy (Chapter 8). Boston, MA: Kluwer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Derivation of the aggregate price level

The pseudo-reduced form equation for the aggregate price level is calculated in three steps: First, I define aggregate consumption as a function of the aggregate price index and the exogenous money supply, which lets me define the wage rate as a function of the exogenous money supply and underlying preference parameters. Second, I find the firm’s pricing rule in terms of expected aggregate consumption and the wage rate. These pricing rules now reduce to a function of the (exogenous) expected money supply and underlying parameters. Third, I substitute these firm pricing rules into the definition of the aggregate price index to redefine the index only in terms of the expected money supply, underlying parameters, and the endogenous cutoff productivity levels for home- and foreign-owned firms operating in the home economy.

1.1 Consumption and wages

Based on the maximization problem described in the text, standard first-order conditions for the consumer’s problem (with λ t representing the Lagrange multiplier for the budget constraint) are as follows:

1.2 The aggregate price level

Minimizing the expenditure necessary to consume one unit of the aggregate consumption bundle gives the aggregate price index in this CES framework shown in the main text,

It is useful now to identify firms by their productivity parameter, \(\varphi \), rather than the firm subscript, i. Every firm draws its productivity parameter independently from an identical distribution, \(G(\varphi )\), allowing me to use the law of large numbers to assert that the distribution of productivity levels for the economy as a whole will be the same as the firm-specific distribution. Then, substituting in the pricing rules, we have

where

1.3 Determinacy

As long as there is a unique solution for \(\hat{\varphi}_{h,t}\) and \(\hat{\varphi}_{f,t}\), there is a unique solution for the price level. In a model where these two variables enter the zero-profit conditions with no other endogenous variables, one can show analytically that the zero-profit conditions are monotonically increasing in these cutoff productivity levels. In this model, an analytical proof is not possible due to the presence of the takeover price V(0), so I use numerical analysis to verify that \(V_{h}(\varphi )\), or Eq. 6 from the main text, is monotonically increasing in \(\varphi \), implying the existence of a unique solution for \(\hat{\varphi}_{h,t}\). Specifically, I calibrate the model as described in “Appendix 4”, setting interest rate volatility in both countries to 0.1 (the particular value for volatility does not affect the monotonicity). Then, I specify values of \(\varphi \) such that \(1<\varphi <\infty \) and solve the system described in the text omitting the equation for \(V_{h}(\varphi )\) (that is, \(V_{h}(\hat{\varphi}_{h,t}))\) so that all other endogenous values are solved for given the level of \(\varphi \) specified. Finally, I numerically compute \(V_{h}(\varphi )\) given the solution values of all other endogenous variables corresponding to various values of \(\varphi \) and find that it is, indeed, monotonically increasing in \(\varphi \). Footnote 14

Appendix 2: First-order conditions for the firm’s problem

To set prices for the following period, firms maximize the expected value of profits with respect to the prices they will set subject to the demand equations in the text [derived explicitly in the technical appendix for Russ (2007)],

for home-owned firms and

for foreign-owned firms. The first-order conditions for firms operating in the home market are then

Assuming that firms take all competitors’ prices (and the aggregate price level) as given, substituting the equations for goods demand, and the derivatives of the goods demand equations, the first-order conditions reduce to

as in Bacchetta and van Wincoop (2000). Reduced forms can be obtained by substituting Eqs. 29 and 1 and 2, yielding the pricing rule in the main text.

Appendix 3: Deriving the impact of home and foreign volatility on multinational firm entry

Starting with the entry condition for foreign firms considering entry into the home market,

one can use the definition of d * t to obtain

Substituting the consumption and pricing equations from the main text, we have

In this paper, the objective is to compare entry across steady states. In a steady state, agents expect the one-period-ahead forecast of the nominal exchange rate and functions of the nominal interest rate to be constant across all future periods. In steady state, the number of active firms from abroad and the price level are also constant. That is, for all k ≥ 0,

Substituting the equations for the demand for an individual good and the moments of the money supply, the pricing rule, and the wage relation, the value function above reduces further to Eq. 19 in the main text.

Appendix 4: Calibration and data

Parameters are assigned the following values: β = 0.96, θ = 7 (between the standard values of 2 and 11 used in international macroeconomics literature), k = θ (to ensure the boundedness of the variance of output-weighted average productivity and make the distribution of firm size a power law as in the trade literature), κ = 1, γ = 1 < 1/β, f = 0.2, ρ = 2, and η = 0.5 (meaning half of all active domestically owned firms must purchase a marketing and distribution facility).

Please see Table 7 for summary statisics pertaining to data used in the econometric analysis.

About this article

Cite this article

Russ, K.N. Exchange rate volatility and first-time entry by multinational firms. Rev World Econ 148, 269–295 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-012-0124-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-012-0124-3